Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 15. The Unmasking of Harold Brown

ON AUGUST 25, just a few weeks after the hearings ended, the New York Sun published stunning revelations regarding Edison's interest in the electrocution law and his relationship with Harold Brown. "FOR SHAME, BROWN!" the newspaper's headline read. "Disgraceful Facts About the Electric Killing Scheme; Queer Work for a State's Expert; Paid by One Electric Company to Injure Another."

The Sun had gained possession of nearly four dozen letters—stolen from a locked desk in Brown's office, it was later revealed—between Brown and the officers of two electrical manufacturers, Edison Electric and Thomson-Houston. The newspaper first ran a brief excerpt from the Kemmler hearings in which Referee Becker had asked Brown if he was "connected in any way with any of the electric lighting companies," and in particular if he had "any connection with the Edison Company … or Thomas Edison." Brown's reply had been "No, sir." The Sun then reproduced a letter Brown subsequently received from his father, who wrote, "I was a little surprised at your statement that you were not connected with any electric company. I thought you were." The rest of the letters—reprinted in full in the Sun—proved that Brown's father was right, although the arrangements were more complicated than the critics of Brown had imagined.1

The Sun printed a letter Brown received in February 1889 from Frank Hastings, the secretary-treasurer of the Edison Electric Light Company, asking Brown to send a copy of his pamphlet The Comparative Danger of the Alternating and Direct Currents to all of the "legislators and officers of the State of Missouri," who were considering a bill that would limit the voltage of alternating current. The cost of printing and mailing the pamphlet to every legislator in Missouri must have been enormous, and Brown was not a wealthy man. The tone of Hastings's letter made it clear that he was giving Brown instructions in the matter; Edison Electric probably paid for the printing and mailing costs as well.2

A month later, in March 1889, Brown sent a letter to Thomas Edison, explaining that he was trying to persuade the city of Scranton, Pennsylvania, to place restrictions on alternating current. Brown said that if Edison would publicly endorse his efforts, he would be able "to add Scranton to the list of cities which have shut out the high-tension alternating current." Edison told Brown that he would be happy to oblige.

My Dear Sir:

I have your letter of 17th instant., and take much pleasure in enclosing herewith a testimonial signed by myself, which I hope will answer your purpose.

Yours very truly,

Thomas A. Edison.3*

A few days later, after winning the state contract to supply execution equipment, Brown wrote to Edison with another request. The generators would cost thousands of dollars, Brown explained, but the state would not repay him until after the first prisoner was electrocuted. He could undertake the plan only "if $5000 is made available" for him to use, and he needed Edison's help in acquiring that money.

In view of the approaching consolidation, the people at 16 Broad street do not feel like undertaking the matter unless you approve of it. Do you not think that it is worth doing, as it will enable me, through the Board of Health, to shut off the overhead alternating current circuits in the State, and will, by showing the lack of efficiency of the Westinghouse apparatus, head off investors, and prick the bubble, thus helping all legitimate electrical enterprises? A word from you will carry it through, and without it the chance will be lost. Is it not worth while to say the word?

"16 Broad street" was the Manhattan address of the Edison Electric headquarters. The "approaching consolidation" referred to the creation of Edison General Electric through the merger of the Edison Electric Light Company with the separate Edison manufacturing enterprises, a deal that was finalized later that spring. Brown's letter indicated that Edison Electric's managers had already agreed to give him the money, but that they also wanted the approval of Edison, who controlled the manufacturing companies.4

Edison's reply never surfaced, but he must have agreed to give Brown the $5,000, because in May Brown wrote to Edison again: "Thanks to your note to Mr. Johnson [president of Edison Electric] I have been able to arrange the matter satisfactorily; have supplied the State with Westinghouse execution dynamos."5

Because George Westinghouse had refused to sell his generators for the purposes of execution, Brown secured them through a second partner, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company. In April and May Charles Coffin, the president of Thomson-Houston, located several utility companies that owned Westinghouse generators and made arrangements to buy those machines and replace them with Thomson-Houston alternating generators. Brown used the money provided by Edison Electric to buy the Westinghouse dynamos from Thomson-Houston. On May 23 Thomas Edison, whom Brown had kept apprised of these arrangements, made an enigmatic statement to a Pittsburgh Postreporter: "The Westinghouse people deny the report, I know, but their machines were certainly purchased, although they may not have been obtained direct from the company." Only with the publication of the Sun letters three months later did the public understand what he meant.6

Charles Coffin helped Brown because he hoped to hurt Westinghouse—not on the safety issue (as Edison did) but through a comparative test of dynamo efficiency. Westinghouse's advertisements claimed that his generators were 50 percent more efficient than those of other companies. In an open letter published in several newspapers, Brown challenged Westinghouse to send one of his alternating generators to Johns Hopkins University, where a professor would compare its efficiency with a competitor's machine. When Westinghouse refused to cooperate, Brown arranged to loan one of the Westinghouse execution dynamos to Johns Hopkins. The Sun letters showed that Brown was working as an agent for Thomson-Houston in arranging this test. Brown told Coffin that he planned to mail copies of the efficiency challenge all over North America in an effort to undermine Westinghouse, and Coffin agreed to pay Brown $1,000 for "expense attending the Baltimore test." Coffin was so pleased with Brown's work that he promised him $500 more for "future expert services." Coffin expected that the Johns Hopkins tests would prove the Westinghouse generators much less efficient than advertised, thereby boosting the reputation of Thomson-Houston's own machines.7

Coffin had another reason to help Brown: If he failed to supply Brown with Westinghouse generators, Coffin ran the risk that Thornson-Houston generators—which could be just as lethal as Westinghouse's—would be used for executions. Brown warned Coffin of this possibility in a May 13 letter: "If anything happens to that [Westinghouse] machine another make of dynamo will have to be used." Later that month, after some delays in delivery of the equipment, Brown told Coffin that the Westinghouse people were "bringing tremendous pressure to bear to prevent the test and to get other apparatus than theirs used." By securing the Westinghouse dynamos for Brown, Coffin protected the interests of his own firm.8

According to Brown, George Westinghouse was so opposed to the use of his generators for executions that he had sent agents to Auburn prison with orders to sabotage the equipment. The agents, Brown wrote to Coffin, "will cripple it if the liberal use of money will do it. I know of their offering money to some of the prison officials some time ago… . I can assure you that there is a desperate attempt being made to have the use of the Westinghouse dynamo for this purpose a failure."9

Most of the letters reproduced in the Sun related to Brown's negotiations with Thomson-Houston for acquisition of the dynamos. After Brown received the $5,000 he requested from Edison Electric, that company mostly disappeared from the correspondence. Thomas Edison and Arthur Kennelly reappeared in the Sun letters on the eve of the Kemmler hearings to give Brown unsolicited advice about his testimony. "At Mr. Edison's instance, I beg to bring the following consideration before your notice," Kennelly wrote to Brown. He said that the only possible argument against electrocution was that it "may burn the flesh of the criminal." Kennelly and Edison proposed that Brown experiment by sending high-voltage current through a dead body. If the test did not produce "any external injury," Kennelly wrote, it would "effectually silence the mutilation argument." (Apparently, this test was never conducted.)10

BROWN REPORTED the theft of his letters to the police in early September, after they were printed in the Sun, and he offered a $1,000 reward for the return of the originals. The letters were stolen more than a month before they appeared in the Sun, explaining why the last letter in the batch was dated July 18. Franklin Pope, a Westinghouse employee and the editor of the Electrical Engineer, printed information derived from the letters long before they appeared in the Sun. The theft from Brown's desk was a clear case of industrial espionage, carried out by someone who almost certainly was working for George Westinghouse.11

Some of the Sun letters had been faked, Brown claimed, but the only letter he specifically labeled a forgery—the one from Kennelly—is indisputably authentic; the original copy of it can be found in the archives of the Edison laboratory. Original copies of at least two other letters that appeared in the Sun can he found in the same archives.12

The reality of the plot described in the Sun letters is also supported by an internal document from the Thomson-Houston Company. In May, as Thomson-Houston was locating the Westinghouse dynamos for Harold Brown, Elihu Thomson, the firm's cofounder and chief inventor, wrote a letter to Charles Coffin objecting to the alliance with Brown. "Whether the matter ever becomes publicly known or not, although I think it must, I dislike to see steps taken to confer a reputation on Westinghouse apparatus which our own similar apparatus must share," Thomson wrote. Coffin ignored the advice.13

THE SUN ATTACKED Brown for his "crookedness" and said he could not "be trusted as an expert for the State." According to the Electrical World, the letters proved Brown had "been 'on the make' throughout." The Electriciandenounced the "conspiracy against the Westinghouse company" and predicted that the revelation of Brown's letters would provoke "public disgust leading to the repeal of the law."14

Although the press heaped scorn on Brown, it had little to say about the roles of the Edison and Thomson-Houston companies. Typical was the response of the Electrical World, which described Brown as "a man who, by playing off one company against another in various ways and by different subterfuges, has succeeded in making a neat little sum of money for himself." Brown was presented as the mastermind, the electric companies his dupes. This interpretation ignored the evidence of the letters themselves, which showed that both Edison and Thomson Houston eagerly provided Brown with money, expert advice, references, and equipment to further his schemes.15

Following the publication of the letters, Brown betrayed little concern, explaining, "I am opposing the Westinghouse system as any right-spirited man would expose … the grocer who sells poison where he pretends to sell sugar." He even tried to use the letters as a defense against the charge that he was working for Edison. "My fight is against the Westinghouse company, but not in favor of the Edison Company If anything, the letters published show leaning toward the Thomson-Houston system, a rival of the Edison system."16

Brown chose to ignore the letter in which he asked Thomas Edison for $5,000 to purchase the Westinghouse dynamos, and he must have felt fortunate that another batch of documents did not become public at the time. Those records, preserved in the archives of the Edison laboratory, show that Brown's participation in the plot against Westinghouse was even more extensive than the Sun letters indicated.

Whereas the first of the Sun letters was dated January 1889, Brown's involvement in the conspiracy dated back at least as far as the dog experiments of the previous summer. At the Kemmler hearings, Edison, Kennelly, and Brown claimed that the tests in July 1888 had been entirely Brown's idea, but Edison's laboratory records tell a different story. Both Brown and Kennelly testified that the first dog-killing experiments at the Edison lab took place on July 9,1888, but neither mentioned that Brown was not present for this experiment. Kennelly also did not acknowledge that he conducted tests on a fox terrier on July 6, also in the absence of Harold Brown. It is not until July 12 that Kennelly's notebook first notes that the experiments took place "before Mr. H.P. Brown." Brown assisted again on July 14, but on the seventeenth—when two more dogs died—Kennelly wrote in his notebook, "Mr. Brown not present at this experiment." More tests were performed in August and September, when Brown was occupied elsewhere. Rather than instigating the tests, Brown simply assisted in a series of experiments by Kennelly and Edison that were in progress before he appeared at the laboratory and that continued in his absence.17

Private correspondence from the laboratory also shows that Brown's role in the tests was more minor—and Edison and Kennelly's much greater—than any of the men later admitted. In a letter written to the Electrical Review in September 1888, Kennelly explained that although Brown had "taken part in" the tests, "all the experiments made and published on the dogs except at Columbia College have been carried out by your humble servant." In another letter Kennelly made it clear that he performed those tests on orders from Edison, who supervised and directed the labors of all of his assistants: "We are continuing the experiments for Mr. Edison, and can kill a dog now more swiftly than a rifle bullet when desired," Kennelly wrote to Edison Electric official Frank Hastings. "I have lately been trying various experiments on dogs," Edison himself wrote in a letter dated July 13, 1888, acknowledging that the physiological tests were not Brown's but his own.18

The evidence in the Edison archives indicates that, starting in the summer of 1888, Brown worked closely with Edison Electric while publicly maintaining that his only interest was promoting public safety. Although there is no direct proof that he was on the company's payroll, it is likely that he was paid for his services. The campaign against Westinghouse was coordinated by two Edison Electric officials: President Edward Johnson and Secretary-Treasurer Frank Hastings. As Brown prepared for the public dog-killing demonstrations at Columbia College in late July 1888, Hastings arranged for him to borrow equipment 197 from the Edison laboratory. "Mr. Johnson and I are both very much interested in these experiments and are very anxious that everything should be there in time," Hastings wrote to Charles Batchelor, Edison's lab superintendent. "It is of course understood that these materials are to be loaned to Mr. Brown in our interests and at as little expense to us as possible." Hastings acknowledged that Brown's work was promoting the "interests" of Edison Electric.19

Six weeks after the Columbia experiments, in September 1888, Edward Johnson tried to persuade Manhattan authorities to replace drowning with electricity as the method of exterminating stray dogs. "I don't want to buy a Westinghouse machine just now," Johnson wrote to Edison. "Have you an alternating dynamo that will give us 1000 volts which you can loan us for a week or so?" If the demonstration worked, Johnson told Edison, the mayor "says he will have an appropriation made to buy a Westinghouse plant for this purpose." Edison loaned him the dynamo.20

Johnson's pointed mention of Westinghouse's dynamo revealed the motive behind the request: If the city used an alternating generator to kill dogs, it would bolster Edison Electric's claim that alternating current was too dangerous for use in America's homes.

Using Westinghouse machines to kill humans would make the same point even more strongly. By the fall of 1888, the state had still not decided whether to use alternating or direct current for executions. Working with Harold Brown, Edison Electric arranged to kill two calves and a horse before Elbridge Gerry and the Medico-Legal Society in December 1888. According to a letter Brown wrote to Kennelly the day after the experiments, Edison had engaged in some discreet lobbying in favor of execution by alternating current: "The results [of the experiments] were very satisfactory, especially so since Mr. Edison's talk with Mr. Gerry and the members of the committee of course carried great weight." Within a week of the experiments, the medical society advocated alternating current for electrocutions.21

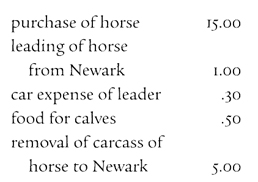

Edison Electric paid for those December experiments. The Edison archives contain an invoice, prepared by Kennelly and submitted to Edison Electric, of "expenses incurred by Mr. Edison in connection with the experiments of electricity on animals [for] the New York committee." The costs included:

Edison Electric financed all of the physiological experiments. The Edison laboratory billbooks contain careful records of all expenses—both materials and labor—connected with the tests and submitted the bills to Edison Electric. Between August 1888 and April 1889, the laboratory submitted six bills totaling $200.29.22

In May 1889, two months after the last of those experiments, Harold Brown secured the state contract to supply execution dynamos, and he used his official position to buy Westinghouse machines. The charges that critics had been making since the first dog experiments in July 1888 turned out to be true: Edison Electric was orchestrating a plot to discredit Westinghouse. Although no single document spells out the plan in detail, the evidence detailed in the Sun letters and in the Edison archives—Hastings's close alliance with Brown, Edison and Kennelly's experiments in dog killing that did not involve Brown, Johnson's promotion of Westinghouse machines for use at the dog pound, and Edison Electric's sponsorship of the experiments—clearly indicate that such a plan was being carried out. Brown's pose as an independent, public-spirited researcher provided cover for his role as attack dog for the Edison interests.

*The testimonial itself did not appear in the Sun; in all likelihood it was not in Brown's desk because it had been sent on to the officials in Scranton.