Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail - Cheryl Strayed (2012)

PROLOGUE

The trees were tall, but I was taller, standing above them on a steep mountain slope in northern California. Moments before, I’d removed my hiking boots and the left one had fallen into those trees, first catapulting into the air when my enormous backpack toppled onto it, then skittering across the gravelly trail and flying over the edge. It bounced off of a rocky outcropping several feet beneath me before disappearing into the forest canopy below, impossible to retrieve. I let out a stunned gasp, though I’d been in the wilderness thirty-eight days and by then I’d come to know that anything could happen and that everything would. But that doesn’t mean I wasn’t shocked when it did. My boot was gone. Actually gone.

I clutched its mate to my chest like a baby, though of course it was futile. What is one boot without the other boot? It is nothing. It is useless, an orphan forevermore, and I could take no mercy on it. It was a big lug of a thing, of genuine heft, a brown leather Raichle boot with a red lace and silver metal fasts. I lifted it high and threw it with all my might and watched it fall into the lush trees and out of my life.

I was alone. I was barefoot. I was twenty-six years old and an orphan too. An actual stray, a stranger had observed a couple of weeks before, when I’d told him my name and explained how very loose I was in the world. My father left my life when I was six. My mother died when I was twenty-two. In the wake of her death, my stepfather morphed from the person I considered my dad into a man I only occasionally recognized. My two siblings scattered in their grief, in spite of my efforts to hold us together, until I gave up and scattered as well.

In the years before I pitched my boot over the edge of that mountain, I’d been pitching myself over the edge too. I’d ranged and roamed and railed—from Minnesota to New York to Oregon and all across the West—until at last I found myself, bootless, in the summer of 1995, not so much loose in the world as bound to it.

It was a world I’d never been to and yet had known was there all along, one I’d staggered to in sorrow and confusion and fear and hope. A world I thought would both make me into the woman I knew I could become and turn me back into the girl I’d once been. A world that measured two feet wide and 2,663 miles long.

A world called the Pacific Crest Trail.

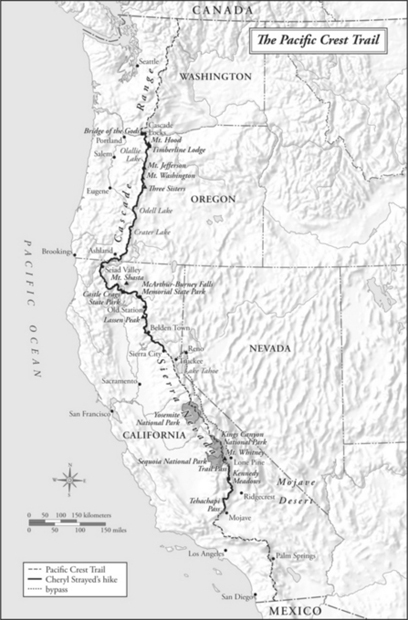

I’d first heard of it only seven months before, when I was living in Minneapolis, sad and desperate and on the brink of divorcing a man I still loved. I’d been standing in line at an outdoor store waiting to purchase a foldable shovel when I picked up a book called The Pacific Crest Trail, Volume 1: California from a nearby shelf and read the back cover. The PCT, it said, was a continuous wilderness trail that went from the Mexican border in California to just beyond the Canadian border along the crest of nine mountain ranges—the Laguna, San Jacinto, San Bernardino, San Gabriel, Liebre, Tehachapi, Sierra Nevada, Klamath, and Cascades. That distance was a thousand miles as the crow flies, but the trail was more than double that. Traversing the entire length of the states of California, Oregon, and Washington, the PCT passes through national parks and wilderness areas as well as federal, tribal, and privately held lands; through deserts and mountains and rain forests; across rivers and highways. I turned the book over and gazed at its front cover—a boulder-strewn lake surrounded by rocky crags against a blue sky—then placed it back on the shelf, paid for my shovel, and left.

But later I returned and bought the book. The Pacific Crest Trail wasn’t a world to me then. It was an idea, vague and outlandish, full of promise and mystery. Something bloomed inside me as I traced its jagged line with my finger on a map.

I would walk that line, I decided—or at least as much of it as I could in about a hundred days. I was living alone in a studio apartment in Minneapolis, separated from my husband, and working as a waitress, as low and mixed-up as I’d ever been in my life. Each day I felt as if I were looking up from the bottom of a deep well. But from that well, I set about becoming a solo wilderness trekker. And why not? I’d been so many things already. A loving wife and an adulteress. A beloved daughter who now spent holidays alone. An ambitious overachiever and aspiring writer who hopped from one meaningless job to the next while dabbling dangerously with drugs and sleeping with too many men. I was the granddaughter of a Pennsylvania coal miner, the daughter of a steelworker turned salesman. After my parents split up, I lived with my mother, brother, and sister in apartment complexes populated by single mothers and their kids. As a teen, I lived back-to-the-land style in the Minnesota northwoods in a house that didn’t have an indoor toilet, electricity, or running water. In spite of this, I’d become a high school cheerleader and homecoming queen, and then I went off to college and became a left-wing feminist campus radical.

But a woman who walks alone in the wilderness for eleven hundred miles? I’d never been anything like that before. I had nothing to lose by giving it a whirl.

It seemed like years ago now—as I stood barefoot on that mountain in California—in a different lifetime, really, when I’d made the arguably unreasonable decision to take a long walk alone on the PCT in order to save myself. When I believed that all the things I’d been before had prepared me for this journey. But nothing had or could. Each day on the trail was the only possible preparation for the one that followed. And sometimes even the day before didn’t prepare me for what would happen next.

Such as my boots sailing irretrievably off the side of a mountain.

The truth is, I was only half sorry to see them go. In the six weeks I’d spent in those boots, I’d trekked across deserts and snow, past trees and bushes and grasses and flowers of all shapes and sizes and colors, walked up and down mountains and over fields and glades and stretches of land I couldn’t possibly define, except to say that I had been there, passed over it, made it through. And all the while, those boots had blistered my feet and rubbed them raw; they’d caused my nails to blacken and detach themselves excruciatingly from four of my toes. I was done with those boots by the time I lost them and those boots were done with me, though it’s also true that I loved them. They had become not so much inanimate objects to me as extensions of who I was, as had just about everything else I carried that summer—my backpack, tent, sleeping bag, water purifier, ultralight stove, and the little orange whistle that I carried in lieu of a gun. They were the things I knew and could rely upon, the things that got me through.

I looked down at the trees below me, the tall tops of them waving gently in the hot breeze. They could keep my boots, I thought, gazing across the great green expanse. I’d chosen to rest in this place because of the view. It was late afternoon in mid-July, and I was miles from civilization in every direction, days away from the lonely post office where I’d collect my next resupply box. There was a chance someone would come hiking down the trail, but only rarely did that happen. Usually I went days without seeing another person. It didn’t matter whether someone came along anyway. I was in this alone.

I gazed at my bare and battered feet, with their smattering of remaining toenails. They were ghostly pale to the line a few inches above my ankles, where the wool socks I usually wore ended. My calves above them were muscled and golden and hairy, dusted with dirt and a constellation of bruises and scratches. I’d started walking in the Mojave Desert and I didn’t plan to stop until I touched my hand to a bridge that crosses the Columbia River at the Oregon-Washington border with the grandiose name the Bridge of the Gods.

I looked north, in its direction—the very thought of that bridge a beacon to me. I looked south, to where I’d been, to the wild land that had schooled and scorched me, and considered my options. There was only one, I knew. There was always only one.

To keep walking.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

To write this book, I relied upon my personal journals, researched facts when I could, consulted with several of the people who appear in the book, and called upon my own memory of these events and this time of my life. I have changed the names of most but not all of the individuals in this book, and in some cases I also modified identifying details in order to preserve anonymity. There are no composite characters or events in this book. I occasionally omitted people and events, but only when that omission had no impact on either the veracity or the substance of the story.