Chaucer (Ackroyd's Brief Lives) - Peter Ackroyd (2005)

Chapter 1. The Londoner

![]()

Chaucer grew up, and found his true place, in what he called “our citee.” He was born, in the phrase of Oscar Wilde, into the purple of London commerce. He did not need to rise through his own individual effort because his position in urban society was comfortable and assured.

His paternal grandparents had come from Ipswich to London, part of that steady influx into the city from the Midlands and East Anglia; London had become the vortex for mercantile activity. His grandfather, Robert le Chaucer, was a mercer who like his grandson eventually entered the king’s service; there was a strong affinity between trade and the court. He was also known as Robert Malyn, the surname meaning “astute.” That was another characteristic he bequeathed to his famous scion. The derivation of “Chaucer” is more uncertain. It may come from chauffecire, to seal with hot wax in the manner of a clerk, but it is more likely to derive from chaussier or shoemaker and hosier. But this in itself has little to do with Chaucer’s family—Robert le Chaucer acquired his name from his quondam master, a mercer named John le Chaucer who was killed in the course of a brawl.

The poet’s father, John Chaucer, was a successful and influential vintner, or wine merchant, who also entered royal service; he was part of Edward III’s abortive expedition against Scotland in 1327, and eventually became deputy butler to the king’s household. In his early youth he was kidnapped by some agents for his aunt and forcibly removed to Ipswich, to take part in a marriage advantageous to that lady, but the aunt was sued and despatched to the Marshalsea prison. It is a bizarre episode but serves only to confirm the sporadic lawlessness and violence of fourteenth-century life. Chaucer’s maternal grandfather, John de Copton, was murdered in 1313 close to his house in Aldgate. The city records reveal that murder, abduction and rape were commonplace; at a later date, as we shall see, Chaucer himself was accused of rape. Agnes de Copton, Chaucer’s mother, was a notable addition to the Chaucer family; she was an heiress, owner of many tenements and of acres in Stepney; in addition she was niece and ward of the Keeper of the Royal Mint.

Geoffrey Chaucer first saw the light, therefore, in a wealthy and influential household. The date of his birth is not certainly known but all the available evidence suggests some time between 1341 and 1343. There is some evidence of a sister, named Katherine, but no contemporaneous record of siblings has been found. He was born in an upper chamber of the family house in Thames Street, which ran parallel to the river in the ward of Vintry, which of course was the district of the wine merchants. The house itself was commodious and well proportioned; in the records it is described as stretching from the river in the south to the stream called the Walbrook in the north, into which all the household refuse was dumped. Anyone who understands the topography of London will realise that this was indeed a large house, which must have possessed a sizeable garden stretching down to the Walbrook at the back. It contained cellars in which the barrels of wine were stored after being unloaded from the wharves a few yards away. On the ground floor, above the cellars and looking out upon the street, was a chamber which acted as his father’s business premises; behind it there would have been a hall, in which the more formal aspects of familial life were conducted. There would have been upper chambers, a kitchen and larder, a privy and perhaps garret rooms.

The neighbourhood itself reflected the solidity and prosperity of the house. It encompassed the dwellings of other rich vintners, some of them with their own court-yards, but it was not necessarily a fashionable area. It was a place of work and commerce. There were several lanes and alleys leading down from Thames Street to the riverside and, in particular, to Three Cranes Wharf where the wines of Gascony were unloaded. A little to the west was Queenhithe to which fish and salt, fuel and corn, were brought in a variety of ships. Chaucer would have known intimately these clamorous thoroughfares—Simpson’s Lane, Spittle Lane, Brikels Lane, Brode Lane most suitable for the passage of the carts, and Three Cranes Lane known in his childhood as Painted Tavern Lane. A few hundred yards away stood the Steelyard, the defended quarters where the German merchants lived and worked; a colony of Genoese merchants was also situated by the riverside, and it has been suggested that Chaucer’s knowledge of Italian sprang from such early contacts. Certainly he came to maturity in a cosmopolitan city.

So we can imagine him standing in one of the principal thoroughfares of London, Cheapside, which he knew all of his life. He was the poet of sunrise rather than of sunset, which is as much to say that he was medieval rather than modern, and at dawn in Cheapside the whole city would awake around him. The bell rang at the church of St. Thomas of Acon, at the corner of Ironmonger Lane, on the hour before sunrise; then the wickets beside the great gates of the city were opened, and through the darkness trailed in the petty traders, the chapmen, the hucksters with baskets of gooseberries or apples, the journeymen, the labourers and the servants who lived outside the walls in the crowded and malodorous suburbs which were the city’s shadow. At dawn the bells in the churches rang to proclaim the ending of the curfew, but already the majority of working citizens were awake and washed. There was a proverbial refrain:

Rise at five, dine at nine,

Sup at five, and bed at nine,

Will make a man live to ninety and nine.

Cheapside was a wide thoroughfare, but also a crowded and noisy one. There were terraces of tall timber houses, rising three storeys, with their gables turned to the street; they projected over the road, and were painted in vivid colours with their framework outlined in intricate patterning. They were built upon stone foundations but were completed with timber framing as well as wattle-and-daub. There may also have been smaller dwellings, of two storeys, and perhaps even a tenement made up of single rooms further divided by partitions for poor families. Certainly these “decaying” houses, as they were known, would have been visible along the lanes and alleys which ran off the main street. Yet Cheapside was known for its shops and its stalls of merchandise. At one end, a few yards past Old Jewry and by St. Mary Woolchurch, stood the Stocks market with its fish and flesh; sited a few yards apart from it were the quarters of the poulterers. At the other end of Cheapside, close to Paternoster Row and the cathedral church of St. Paul, was a large covered market in which tradesmen would sell their wares out of boxes or chests.

But the street was largely comprised of individual shops and sheds packed closely together, one for every ten feet (three metres) of road-space. Each trade had its own area so that, for example, the goldsmiths were situated between Friday Street and Bread Street; within the dim interiors Chaucer would have seen on display the spoons and phials, the rings and necklaces, the crucifixes of silver gilt and paternosters of amber or coral. Friday Street itself was named after the fish market which assembled there on that day, while Bread Street was known for its bakers and its cook-shops where ten eggs or a roast lark could be purchased for a penny and a hen baked in a pasty bought for fivepence. Just past the goldsmiths, between Friday Street and Bow Church, stood the shops of the mercers with their silks and fabrics, while opposite haberdashers sold hats and laces, boots and pen-cases. Other shops sold toys and drugs, spices and small-ware. In Paternoster Row, leading off Cheapside, were the stationers and booksellers with their psalters and calendars, doctrinals and books of physic. The signs of the different trades were suspended on poles, and there were drawings on the wooden walls of the shops as a symbol of what lay within. Most of these ground-floor shops were protected by an overhanging storey, or penthouse, where the shopkeeper and his family would live in one or two rooms. If a house boasted a small cellar or undercroft it would be utilised for storage or for trade, with ale one of the most easily available commodities.

Among the one-storey sheds and the two-storey dwellings, with whitewashed walls and thatched roofs, would be vacant plots and gardens. Down the smaller streets were shops and cottages, fences and barrels, with chickens and ducks, goats and pigs, roaming among them. Most of the pavements would have needed repair, and there were piles of refuse or manure on the streets waiting for the “raker” or “fermour” to remove them. The air was filled with the smell of burning wood and of sea-coal, of cess pits and butchers’ waste.

At sunrise the great gates of the city were opened, and the long bakers’ wagons from Mile End would bear their precious burden into the streets of the city; simnel bread was best, and cocket the worst. Horses and carts of every description would also begin their journey through the narrow streets among the porters and water-carriers and merchants. In a city continually expanding, there was building work everywhere. In the latter half of the fourteenth century the population of London has been variously estimated between forty thousand and fifty thousand but, whatever the density, the square mile within the walls was sufficiently noisy and active. The population of London was characteristically compared to a swarm of bees, busily engaged but when threatened dangerous and deadly. Yet the greetings upon the street, at any dawn, would have seemed beneficent enough. “God save you … God give you grace … God’s speed … Good day, a clear day.” Mixed with these greetings the cries of the street-sellers would already be added to the clamour and shouting which accompanied the start of each day. “Twelve herrings for a penny! Hot pies! Good pigs and geese! Ribs of beef and many a pie!” The blind would stand on street corners with their white willow wands and sing such popular songs as “Jay tout perdu mon temps et mon labour,” which Chaucer mentions, and “My love has fared inland.” Chaucer would have thoroughly absorbed the language of the streets, that rich polyglot mixture of Latin patois, Anglo-Norman phraseology and English demotic; it emerges in Chaucer’s consistent hyperbole, so much a feature of London speech, but also in the stray phrases which are embedded in his aureate verse—“Come of, man … lat se now … namoore of this … what sey ye … take hede now … Jakke fool!” At night, and in moments of relative quiet, the sound of the river would clearly be heard.

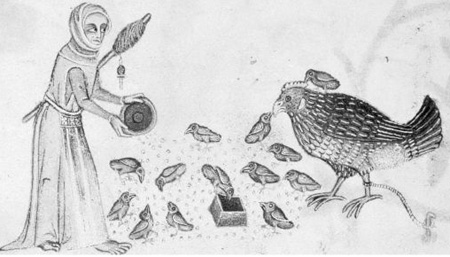

Feeding the chickens, c.1340

An apt symbol for the Catholic culture of fourteenth-century London might be found in the fact that there were ninety-nine churches, and ninety-five inns, within the walls. (The hermitages and oratories have not been included, but neither have the ubiquitous ale-cellars.) In future generations the piety of Londoners was recognised all over Europe, and there is no reason to suppose that the faith of the fourteenth century was any less intense. The celebration of the Mass was at the centre of London worship; the bells pealed out at that blessed moment when the bread is turned into the body of Christ and becomes the eucharist; at that moment, divine life entered and renewed urban time. It was a culture of ceremony and ritual, of hierarchy and display, modelled upon sacred typology and the liturgical year. It is not surprising, therefore, that the poetry of Chaucer is suffused with religious practice and religious personages. The Canterbury Tales is of course itself set within the context of a pilgrimage, and hardly one of those tales is not concerned directly or indirectly with “hooly chirches good.” In that compendium of late medieval narratives there are saints’ tales and pietistic texts. The urban parades and religious processions upon London’s streets, as well as the stridently colourful dress of the citizens, also testify to a culture of spectacle and display. It is a culture in which the ideal and the real interpenetrate one another, so that the most vivid or naturalistic detail within Chaucer’s poetry can be suffused with a sense of the sacred. In the mystery plays, which Chaucer would have witnessed, the events of biblical history are interrupted by farce and obscenity; in “The Miller’s Tale” of The Canterbury Tales, a domestic version of Noah and his ark becomes the occasion for “fart,” “piss” and a “naked ers.” In a civilisation where death and disease were so pressing, and so close to hand, why should there be any conception of “good taste”?

There is a description of London in the twelfth century, written by William Fitzstephen, which furnishes the context for the development of the city in Chaucer’s lifetime. He describes the meadows and springs which lay just beyond the city’s bounds; even in the fourteenth century the sentinels of the city walls and gates looked out over fields, and bells were rung to call in agricultural labourers at curfew time. He mentions the “smooth field,” where horses were raced and purchased, which by Chaucer’s time was known as Smythfelde; it had become the site of a market and a fair, as well as the spot where malefactors were hanged by a clump of elm-trees. It was already a city of violent contrasts. Fitzstephen describes the ancient governance of London with its wards, and sheriffs, and courts. Chaucer himself would have grown up within the network of these obligations which stretched back, in the medieval phrase, “beyond the memory of man.”

His poetry is often conceived to be of springtime rather than of autumn, as if he believed himself to come from a freshly minted civilisation; yet London was deemed to be more ancient than Rome. Fitzstephen’s account concludes with a description of the sports and games of the city. He mentions the dramatised versions of saints’ legends, played out upon the streets, in the same paragraph as he alludes to the cock-fights organised by schoolboys at Shrovetide. He describes football and horse-racing, ice-skating and archery, as well as bull-baiting and boar-baiting by savage dogs. In the context of these violent delights, he might have mentioned the sporadic but intense violence of Londoners themselves; the city records are filled with reports of riots and murderous affrays, with which Chaucer himself became all too familiar. Fitzstephen adds that the “only inconveniencies of London are, the immoderate drinking of foolish persons, and the frequency of fires.” Since this is a complaint repeated down the centuries, even perhaps into our own time, then we may safely conclude that the city itself has certain unchanging characteristics. When we read Chaucer’s poetry, then, it may speak to us directly.

From the circumstances of the fourteenth century an eternal London vision can emerge. Chaucer is intrigued by crowds and processions; the Canterbury pilgrims themselves form a parade, and the figure of the “verray, parfit gentil knyght” might be that of St. George upon one of the pageant wagons which trundled down Cornhill and Cheapside. Chaucer is preoccupied, also, with variety and contrast in a world where “high” and “low” mingle. His poems are filled with many competing voices, as if he were repeating the accents of the London crowd, and his work is suffused with a theatricality and vivacity that might derive from the contemplation of the endlessly changing urban world. Chaucer is in love with spectacle of every description, and with the external life of humankind. He is a London artist.

As a child he lived beside the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, where no doubt he was baptised on the day after his birth; beside that was a large house of stone and timber known simply as the Vintry. Here dwelled at various times John Gisers and Henry Picard, both vintners and both lord mayors of London. But there were also cook-shops and taverns in the immediate vicinity, for the merchants as well as for those who worked on the wharves; the labour was most intensive between the months of April and June, when “the wines of rack” arrived, and in November for “the wine of vintage.” One stretch of Thames Street was known as “cooks’ row” so that, according to the sixteenth-century London antiquary John Stow, “in those days (and till of late time) every man lived by his professed trade, not any one interrupting another: the cooks dressed meat and sold no wine, and the taverner sold wine, but dressed no meat for sale.”

The infant Chaucer was brought up in a richly furnished household. The general reports of merchants’ houses suggest a fair degree of comfort; deep feather-beds, cushions, tapestries and embroidered hangings are characteristically included in any inventory of domestic effects. The modern notion of the medieval house seems to consist of cold stone, bare walls and malodorous corners, but in fact the more prosperous households would have been comfortable, colourful and clean. The wooden sideboards would be filled with silverware, an obvious token of wealth, and the walls would be decorated with tapestries or murals. The clothes of these householders were similarly designed for comfort as well as display. We may imagine the juvenile Chaucer in an undergarment of woollen cloth surmounted by a loose woollen tunic that hung down to his ankles.

Butchering and cooking meat, and carrying it to the table, c. 1340

It is not possible at this late date completely to re-create the atmosphere of Chaucer’s family home. In his poetry mothers are celebrated as tender emissaries of a largely patriarchal society; they are patient and benign, meek and gentle. It would be unwise, however, to interpret his life in terms of his art. The women of his poetry also tend to be deserted and betrayed, for example, although there is no evidence that Agnes de Copton experienced any such fate. It has also been observed that “father figures” in Chaucer’s poetry are noticeable by their absence but, again, no proper conclusions can be drawn.

His father did intervene in Chaucer’s life in one decisive period, however. In 1347, as part of his official duties as deputy butler in the king’s household, he was despatched with his family to Southampton in order to supervise the collection of import duties upon wine; the year after the Chaucers left London the city was visited by “the death,” later named the “Black Death” after the black buboes which swelled upon the victim’s body. It has been estimated that 30 per cent of the English population was destroyed by the epidemic of 1348-49. In the unnaturally crowded and noisome conditions of London we may suppose the mortality to have been significantly higher, but no reliable estimates are extant. It is safe to assume, however, that when the Chaucer family returned to Thames Street in late 1349 or early 1350, they found a much emptier city. The effect upon the young Chaucer can only be inferred. The only reference to a plague epidemic occurs in “The Pardoner’s Tale”:

Ther cam a privee theef men clepeth Deeth

That in this contree al the peple sleeth.

But it is merely an elaboration within an ironic moral homily on the sin of avarice.

It is suggestive that Boccaccio’s Decameron, which may have influenced the design of The Canterbury Tales, was conceived as a series of stories designed to alleviate the pressing miseries of the plague. It has been supposed that Chaucer’s well-attested absorption in books springs directly from his experience of a threatening and uncertain reality; that he was possessed by the idea of reading as the image of a secure world. There may be some truth in this but it would be unwise to project a modern sensibility upon a medieval mind. The citizens of fourteenth-century London, in particular, were inured to death and disease in all of its forms; it should be remembered, too, that for them death was only one stage of an eternal drama. The consequences of the plague epidemic were for the Chaucer family considerably more benign, in any case, since they inherited a great deal of property from the last bequests of those relatives who had unfortunately remained in London.

On his return to the city it might be assumed that Chaucer’s schooling began in earnest, except that there is no indication of what that schooling consisted. The education of a prominent citizen’s son characteristically began at the age of seven in a “song school” or “grammar school” where Latin phrases were learned by rote; Geoffrey Chaucer might equally have been taught at home, or even by the priest of St. Martin Vintry. Many scholars have acquiesced in the notion that he was sent to St. Paul’s Almonry School, just a short walk away, if only to explain how the poet acquired his knowledge of Latin and of Latin authors such as Ovid and Virgil. Here he would have learned the Latin grammar of Donatus, known to generations of schoolboys as the “Donat,” as well as more advanced rhetorical and grammatical treatises; here, too, the Latin was as likely to be translated into French as into English, an indication that the Anglo-Norman ascendancy had not wholly faded. All this is supposition and speculation, however, compounded by the nervous belief that Chaucer’s genius must have in part depended upon a formal and hierarchical education. The problem is that no evidence can be furnished to support that belief. One possible source of instruction, however, lies closer to home. A written compendium of English texts, assembled by a London bookshop around 1330, has become known as the “Auchinleck Manuscript”; it contained more than fifty items, including seventeen English romances as well as saints’ lives and satires, and has been credibly associated with the Chaucer household itself. Certainly some similar anthology would have been known to the young Chaucer. Like Shakespeare Chaucer nurtured his genius by absorption and assimilation; his early exposure to English texts would, in that sense, have been highly significant. His was a thoroughly native genius.