Chaucer (Ackroyd's Brief Lives) - Peter Ackroyd (2005)

Chapter 12. Last Years

![]()

There are more than eighty extant manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales, all of them compiled after Chaucer’s death, which testify to the immediate popularity of the long poem. In the last years of his life he may have circulated individual tales, or bundles of tales, to his friends and contemporaries; one or two may have found their way to the court. He had not lost all contact with that world. The evidence of his various appearances as a “witness” indicates his residence in Kent; he was present both at Woolwich and at Combe, no doubt for a fee, to witness charters of release and transfers of property. He was also appointed by a local landowner, Gregory Ballard, to act as his attorney. But the royal associations were kept in place. At the beginning of 1392 Richard II awarded him ten pounds for good service; this suggests, although it does not prove, that Chaucer was still engaged in some form of royal employment. No evidence of this has ever come to light, but it might be related to some duties in Kent itself.

On 28 February 1394 Richard II bestowed upon Chaucer an annual grant of twenty pounds “pro bono servicio”; this was in effect a pension, renewing that which Chaucer had sold to John Scalby six years before. There are several records of Chaucer asking for a “prest” or advance upon the annuity, however, which suggests that he was not necessarily living in affluence; in the same period, too, he was sued for the recovery of a debt of some fourteen pounds. In 1397 the king also granted Chaucer, as a good and faithful public servant, a tun or large cask of wine each year; in the manner of all bureaucracies the gift was not presented on time, and in the following year Chaucer petitioned the exchequer on his own behalf for delivery of the wine.

The award of the exchequer annuity, however, was not necessarily an indication of complete retirement; the terms of the grant itself suggested further public service “in futurum.” That was not necessarily an idle or conventional formula. In 1398 Chaucer was given a “safe conduct” for the pursuit of the king’s “arduous and urgent business” over a period of two years; the nature of his mission is unknown, but it does not seem to have involved any journey overseas. It may have been a procedure, however, to protect Chaucer from any legal action concerning his debts. It is at least an indication that the poet was still noticed by the authorities, as a man either to be defended or to be summoned on the king’s behalf. As visible proof of his merit Chaucer was also rewarded by Henry Bolingbroke with a scarlet gown lined with fur, before his benefactor came to the throne as Henry IV. Chaucer was still a “high person.”

He was, in any case, about to leave Kent and to return to London. He may have grown tired of the relative quiet of the country and longed once more for the noise and bustle of the city. He was coming to the end of his life, and wished to return to his origin. He may simply have grown restless. It has often been said by poets and artists that a change of scene materially helps the process of composition. He returned to the city in 1398, two years before his death, and in the following year took out a fifty-three-year lease upon a “tenement” in the garden of the Lady Chapel of the abbey in the adjacent city of Westminster. He was in possession of a small but comfortable house, with garden, in the precincts of a great and ancient church; it may have seemed to him a place conducive to the further writing of The Canterbury Tales. The length of the lease is perhaps odd in a man of advancing years, but it may have been a legal fiction. It was the equivalent of “grace and favour” accommodation, since the same house had in the past been leased to retired royal servants. It was part of the area of the abbey’s sanctuary, but that does not necessarily mean that it was a sheltered or secluded spot. The poet would have seen from his window the south transept of the abbey, but he was in the immediate vicinity of the White Rose tavern which was also in sanctuary grounds.

In the autumn of 1399 Richard II was forced to abdicate by the superior forces of Henry Bolingbroke, who had returned from exile in France with the express purpose of overthrowing the king of England. When he ascended to the throne as Henry IV, however, the new king renewed Chaucer’s annuity and confirmed the earlier grant of a cask of wine; Chaucer also received an additional payment of forty marks (approximately twenty-seven pounds) as a sign of royal favour. It may be an indication of the poet’s relative lack of significance. It suggests the impersonality of the bureaucracy around kings, when a major shift of loyalty can be regarded simply as a change of employer. But it also suggests Chaucer’s modest or noncommittal deportment in the affairs of state, that he could be regarded as “dilectus armiger noster” by both sovereigns: his long-time benefactor Richard II, and also the man who overthrew Richard in order to make himself Henry IV.

There was in fact a delay in the payments, and the sudden lack of funds prompted Chaucer to address a begging poem to the new king entitled “The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse”:

To yow, my purse, and to noon other wight

Complayne I, for ye be my lady dere.

I am so sory, now that ye been lyght …

For I am shave as nye as any frere.

So Chaucer had returned to the city of his birth or, more precisely, to the city of Westminster further along the Thames. He was, in theory, sufficiently well rewarded for his years of service. The last two payments of his annuity were not made to him in person, however, which may suggest that he was already in ill-health. One account by the sixteenth-century antiquarian, Leland, suggests that the poet “grew old and white-haired”; he was now approaching sixty, not an advanced age but in a period of chronic illness and sudden death a respectable one. Leland also relates how Chaucer believed “old age itself to be a sickness,” but that may simply be a chronicler’s commonplace.

There are apocryphal references to Chaucer’s last years in an account which suggests that, before his death, Chaucer cried out “Woe is me! Woe is me!” in regret for the bawdy poems that he had written. Since he had already composed a public retraction, such private grief seems unlikely. It has in fact been suggested that the last work he ever completed on The Canterbury Tales concerned the obscene tales of “Group A,” from the Miller, the Reeve and the Cook. It would be a fitting end to the career of a quintessentially urban writer.

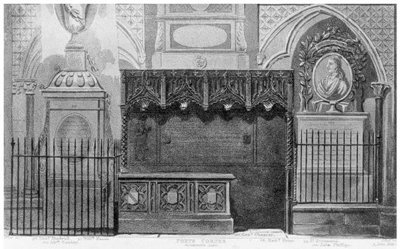

The cause and manner of his death are not known; he expired, however, in a year of plague. The generally accepted date, 25 October 1400, was taken from the inscription upon a tombstone erected some 150 years later. That tomb rests in the south transept of Westminster Abbey, Chaucer’s tomb, in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey now known as “Poets’ Corner.” Originally Geoffrey Chaucer was buried in an obscure site, generally left for monastic officials, by the entrance to St. Benedict’s Chapel; he seems to have been granted no elaborate service or ceremonial, but to have been buried as the role and rank of a minor court servant deserved. He remained circumspect, and reticent, until the end.