When I left home: my story (2015)

After I Left Home

First Time I Met the Blues

Gotta say that the first time Willie Dixon told me he was cutting a record on me, it took me by surprise.

“Wasn’t easy,” he said. “Leonard ain’t that impressed by you as a solo man. He sees you strictly as backup. He thinks you good as backup, but that’s as far as it goes. I told him differently. I said, ‘I seen Buddy Guy tear the roof off Theresa’s. That ain’t no goddamn backup.’”

“I know I can the tear the roof off a record,” I said.

“That’s just the point—you can’t. Leonard likes his records a certain way. You can’t get all wild like you do on stage. Can’t play too crazy. Can’t fuck up the sound none like I seen you do in the clubs. Leonard likes his blues clean.”

“You got the songs you want me to do?”

“I got all the songs you need.”

“I got some songs I wrote myself.”

“Well, we’ll do mine first. Then we’ll worry about yours.”

The first one I cut wasn’t written by either of us. It was a thing by Little Brother Montgomery called “First Time I Met the Blues.” When it came out, some people said I sounded like B. B. King, and I took that as a compliment. Who didn’t wanna sound like B. B.? I liked the opening line that Little Brother wrote: “The first time I met the blues, I was walking down through the woods.” I liked closing my eyes and pretending I was back home in them woods. Also liked that I had Otis Spann, the Mud’s man, on piano, and Fred Below on drums. That same day I sang a song Willie put his name on—“Broken-Hearted Blues”—but everyone seemed to like “First Time” better.

Day after the session Willie told me that Leonard was putting out “First Time,” but on one condition.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“He wants you to change your name.”

“Why don’t he like my name?”

“Ain’t that he don’t like it,” said Willie. “It’s just he thinks you should be a King.”

“What does that mean?”

“You know, you call yourself Buddy King or King Guy—something like that.”

“Don’t see the point. People might get me confused with B. B. or Freddie King.”

“That’s just the confusion Leonard wants. Only he calls it association. ‘King’ is associated with strong-selling blues.”

“Muddy don’t got no king in his name.”

“He came through before the kings.”

“Well, I’m coming through after.”

“Buddy King sounds real good.”

“Maybe, but it ain’t me. Besides, when they play the record in Baton Rouge and the deejay calls out, ‘Buddy King,’ my people won’t know it’s me.”

“You can tell your people ahead of time.”

“That’s ain’t good enough. I want my mama and daddy to hear the name they gave me over the radio.”

“Leonard won’t be happy.”

“I won’t be happy if I don’t go by my right name.”

“You’re gonna hold stubborn?”

“If you mean, am I gonna hold on to my name, yes, sir, I am.”

I did, and I guess Leonard Chess thought “First Time I Met the Blues” was good enough to put out under Buddy Guy. When I went home to Louisiana for Christmas, I learned that they did play it on WXOK, causing my family and friends happiness and pride.

In the first few years of the sixties every now and then Chess recorded me. Sometimes Willie let me keep my name on songs I had written, but I was never told nothing about the publishing rights of the composer. I didn’t know those rights belonged to me, and I didn’t know that if they were transferred to someone else—like the Chess Brothers’s publishing company—I should have been paid. Payment wasn’t on my mind—I just wanted to make it.

Chess thought that if I was going to make it, I’d have to make it in the mold of a B. B. or a Freddie. They tried some instrumentals out on me, and they even tried some ballads, but nothing caught on. If I started in on what had become my live style—twisting the notes real hard, playing riffs that sounded like they came from outer space, letting the tape buzz and bleed with different combinations that caught your ear—Leonard would say, “Buddy, you’re doing too much. Play less. Calm your ass down.”

I’d be a fool to argue, so I didn’t. Leonard was holding all the cards, and I was at the bottom of the Chess totem pole. At the same time, I was still a young man in my mid-twenties. Having my own records out there impressed everyone … except my father-in-law. When me and my wife showed him that 45 of “First Time I Met the Blues,” he said, “They give you this record instead of money?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“I mean, did they hand you cash for playing this here record?”

“No, but I signed a contract that says if it sells a certain amount, I get paid royalties.”

He laughed in my face. “Son,” he said, “when those royalties come in, dogs gonna be fucking pigs.”

The man was right. He was saying the same thing Lightnin’ Hopkins had said. Deep down, I agreed, but was too proud to admit it.

Wasn’t too proud, though, to double-up my work. I needed money and wasn’t afraid to go after it.

When Elmore James, for example, told me I could make good money playing this gig with him down in Texas, I figured it was far away but worth it. We piled into Elmore’s station wagon and drove to a roadhouse just below the Arkansas-Texas border. Place was packed. We played three long sets and were ready for the long ride back. Time to get paid.

Big bear of a man came to the bandstand while we was putting away our instruments. He was the guy who called Elmore for the gig.

“Bad news,” said the bear.

“What bad news?” asked Elmore.

“We done got robbed.”

“I didn’t see no robbery.”

“Happened out back. We clean out of money.”

“That won’t do,” said Elmore.

“Gonna have to do,” said the bear.

“Oh, man, this is some fucked-up shit,” said Elmore. “Least you can do is give us gas money to get back to Chicago.”

Bear refused.

Elmore started screaming at him, which is when the bear put a gun to his head. That got us to leave without no more arguing.

We had enough gas to get to East St. Louis, where we had to beg strangers to give us $5, which took us to the Chicago city limits. From there I reached in my pocket and used my last fifteen cents for bus fare home.

This made me reevaluate my situation: loved music more than anything. Would rather play music than anything. But playing music wasn’t paying my bills. So when I had a chance at a steady job, I took it. It happened when a man in Joliet asked me to manage his club. He saw that not only could I play, but I could also organize. I could get names like Wolf, Walter, and Muddy down there. Joliet’s only forty-five minutes from Chicago, and using my rhythm section like I had in Gary, I could convince big-name bluesmen to come in, do a few songs, and make it back to their regular gigs in time for their late sets. To kick things off, though, I thought it best to get one of the stars to play from ten to two. Because I wanted the music fans in Joliet to know I wasn’t fooling around, I booked Sonny Boy Williamson. (This is Sonny Boy 2; I never knew the original Sonny Boy.)

Club 99 was a good-sized room. Owner gave me a little room in the back so, after playing Friday night till 4 or 5 a.m., I could sleep and be right there to get ready for Saturday.

On this particular Saturday morning the owner came to my room to say that Sonny Boy had arrived for that night’s gig and was at the bar drinking.

“What time is it?” I asked.

“Not yet noon. You better go out there and see about him.”

I went out and saw Sonny Boy sitting in front of a fifth of whiskey.

“Morning,” I said.

“Morning, motherfucker.”

“You here bright and early.”

“Damn right,” he said. “Had nothing to do today, so I figure this is good a place as any to pass the time.”

Owner whispered in my ear, “He ain’t gonna be fit to play tonight. Say something.”

Knowing Sonny Boy, I decided saying something wouldn’t be wise.

Later that same afternoon I was napping when the owner came back knocking at my door.

“Your friend’s still at the bar,” he said, “still drinking.”

Just then I heard the sound of his harp. Went out to the club, and there was Sonny Boy, playing his harmonica to the woman cleaning up the bar. When he blew harp, he could do it without hands. He’d curl his upper lip to hold the harmonica and blow it with his nose. You wouldn’t think that could sound good, but Sonny Boy made it sound great. The gal had a smile across her face, and Sonny Boy had another big fifth set in front of him.

“Say something,” said the owner.

Hadn’t changed my mind. I knew these guys. They weren’t the kind who could be told when and when not to drink. I left him alone, but I admit I was worried. In just a few hours I’d be calling him to the stage. I was afraid that he’d never make it—or, like Jimmy Reed, he’d fall on his face. If that happened, the crowd would start booing and I’d probably lose this job.

Come 9:30, it was time to hit. Sonny Boy was nowhere in sight. The owner gave me a look like I had murdered his mother.

“Where the fuck is that harmonica player? I told you he was going drink himself into the gutter. What you gonna do now?”

“We’ll heat up the crowd with a few warm-up numbers,” I said.

Up on stage, I kept looking around for Sonny Boy. The man was still missing.

Finally, after playing a third song, I knew it was star time. Everyone had come to hear Sonny Boy Williamson. I figured I might as well give it a shot. What else could I do?

“Ladies and gentleman,” I announced. “Let’s give a warm welcome to the great Sonny Boy Williamson!”

Ten seconds passed. The owner looked at me and I looked back at him. He shrugged, and then I shrugged, and then out of nowhere Sonny Boy Williamson jumped on that stage with the energy of a teenager. At that time he had to be seventy, but you’d never know it by how he moved. He started in with “Don’t Start Me to Talkin’,” went into “Keep It to Yourself” and “Fattening Frogs for Snakes,” and then burned down the house with the song that says, “Stop your off-the-wall jive … if you don’t treat me no better, it’s gonna be your funeral and my trial.”

Long story short, Sonny Boy played for two straight hours. Around midnight he took a break, but the break only lasted long enough for him to have a couple more drinks. Then he was back up, rocking the joint till 2 a.m. We couldn’t get him off the stage. When he did get off, he made a beeline for the bar and started to drink. Me and the owner were there to thank him for a job well done.

“Fuck both of y’all,” he said. “I heard you talkin’ bad ’bout me this morning. You was saying I was gonna be too drunk to play. Well, lemme tell you something. When I was twenty-nine, doctor says, ‘Sonny Boy, if you don’t put down the bottle you’ll never see thirty-five.’ Guess where that doctor is now?”

“Where?” I had to know.

“Pushin’ up motherfuckin’ daisies.”

We had to laugh.

“So let’s drink to his health,” said Sonny Boy, as we all raised our glasses. “Fuck y’all and fuck the dead doctor.”

Even though I was managing Club 99 in Joliet to make ends meet, I was still gigging in Chicago. I used to play Curly’s at Madison and Holman. I liked Curly and got sad when he said that business was so bad he might have to close up. It was more than me worrying about losing a gig—I hated it when any blues club had to shut down. I took it personally.

“If I brought B. B. King up in here,” I asked Curly, “would that help business?”

“Sure as shit would.”

B. B. was playing Gary. I drove up and told him the situation. “Curly’s a good guy,” I said, “but these other clubs around here are running him out of business. I’d like to help the brother.”

B. B. responded with two words: “Me too.”

So I ran back to Chicago and told Curly B. B. would come in that weekend.

“That ain’t ever gonna happen,” he said. “B. B King ain’t showing up. He don’t give a fuck about saving no blues joint.”

That Saturday night I got to Curly’s around 1 a.m. Club was jammed, but B. B. wasn’t there.

Curly was fit to be tied. Steam was coming off the top of his head. “You and your B. B. King are both no-good, lowdown dogs. I told you he’d never show.”

“But …”

“I don’t hear no buts. I don’t need no lame excuses. Told all these folks they’d get to hear B. B. King, and they looked at me like I was crazy. Well, I was.”

“No you wasn’t,” I said. “He just went to park his car.”

Right then B. B. came walking down the street. You better believe he was carrying Lucille. When he walked into Curly’s, it was like Santa Claus coming down the chimney. Everyone was up and screaming. That night he played for free. Curly’s got a good name and folks started flocking in.

Thing about B. B.—then and now—is his humility. Mama used to talk about a humble heart being a good heart. But in my lifetime I’ve met few genuinely humble people, especially in the music business, where most everyone gets what John Lee Hooker calls the Big Head. B. B. never had no big head. Even today every conversation with him almost gets me to crying because I feel how sincere he is about his love of people and music.

At Curly’s that night, after he got through playing, he wanted to know where we could go to hear good jazz. I knew all the jazz joints because, like B. B., I couldn’t hear enough good jazz. We went down to the Trocadero to catch Gene Ammons—they called him Jug because of how he liked to drink—and sat there till the sun came up, listening to this man crying through his tenor saxophone.

“You know,” I said, “I love this jazz, but sometimes I don’t think the jazz cats love me.”

“Some of ’em can get a little attitude,” B. B. agreed.

“The other day I was standing outside Pepper’s with Jerry, my horn player, when a jazz cat comes up to him and says, ‘Hey, man, who you giggin’ with?’

“Jerry says, ‘Buddy Guy.’

“Cat doesn’t know me. He figures I’m another sideman. He turns to Jerry and says, ‘Buddy Guy? The wild man who comes in off the street with that long cord?’

“‘Yeah,’ says Jerry.

“Cat says, ‘How can you play that shit? How can you play such simple-minded crap?’

“‘I like it,’ says Jerry.

“‘Well, to each his own. By the way, man, can I borrow a couple of bucks?’

“‘No,’ says Jerry.

“‘Well, at least give me a taste of that wine you drinking.’

“‘No.’

“‘How ’bout a hit off that reefer you smoking?’

“‘No.’

“‘Damn, motherfucker, why you gotta be so cold?’

“’Cause I paid for this wine and reefer by playing the music you calling shit. I don’t wanna contaminate you none. But I do wanna introduce you to Buddy Guy. He standing right here.’

“Cat nearly falls out. I just smile and offer my hand. ‘Pleasure to meet you,’ is all I say.”

B. B. laughed and said, “Buddy, I got a story for you. Ran into Miles Davis up in New York. Never met the man before, but he comes up to me and says, ‘You bad, man. You real bad.’ I say, ‘Thank you, Miles.’ He say, ‘Not only are you bad, you can do something I can’t.’ ‘What’s that, Miles?’ ‘I been studying music my whole life,’ says Miles. ‘Went to school. Had all these fancy teachers and fancy courses. But you, you bend one note and make more money in one night than I make in a month.’”

As a money-maker, B. B was always king, but the rest of us, even though we might work regular, struggled hard. That’s why I kept my mouth shut and went along with whatever program I could fit into. If Leonard Chess wasn’t interested in promoting my records, I wasn’t about to complain. The man, after all, was giving me work in the studio. He saw me as a musical plumber. I could fix what needed fixing.

Six one morning the phone rang. It was Willie Dixon. “Leonard wants you to come down to the studio,” he said.

“Tonight?”

“No, motherfucker, right now.”

Didn’t argue. Threw on my clothes and went to 2120. It was a session for the Wolf. You know they’d been drinking all night. But now it was morning, and the happy spirit of the whiskey had turned sour. Everyone looked like they lost their mama. Wolf looked like he was ready to whup everyone’s ass. Leonard Chess looked like he hadn’t slept in a week. He was yelling at Hubert Sumlin that Hubert wasn’t getting this rhythm thing right. Hubert’s a great guitarist, but there was bad communication ’tween him and Leonard.

I was sitting in the corner watching all this when Leonard turned and noticed me.

“How long you been sitting there?” he asked.

“A while,” I said.

“Why didn’t you say something?”

“’Cause no one asked me nothing.”

I was one of these don’t-speak-till-you’re-spoken-to guys.

“Come over here, motherfucker,” Leonard said. “Bring your guitar. Listen to what I’m humming to Hubert.”

I listened.

“You hear it?” Leonard asked.

“I do.”

“Can you play it?”

“I can.”

And I did.

“Shit,” said Leonard, “I’ve been looking to get this lick down for six hours. This guy comes waltzing in and nails it in a minute. Let’s roll tape.”

One take and we was done.

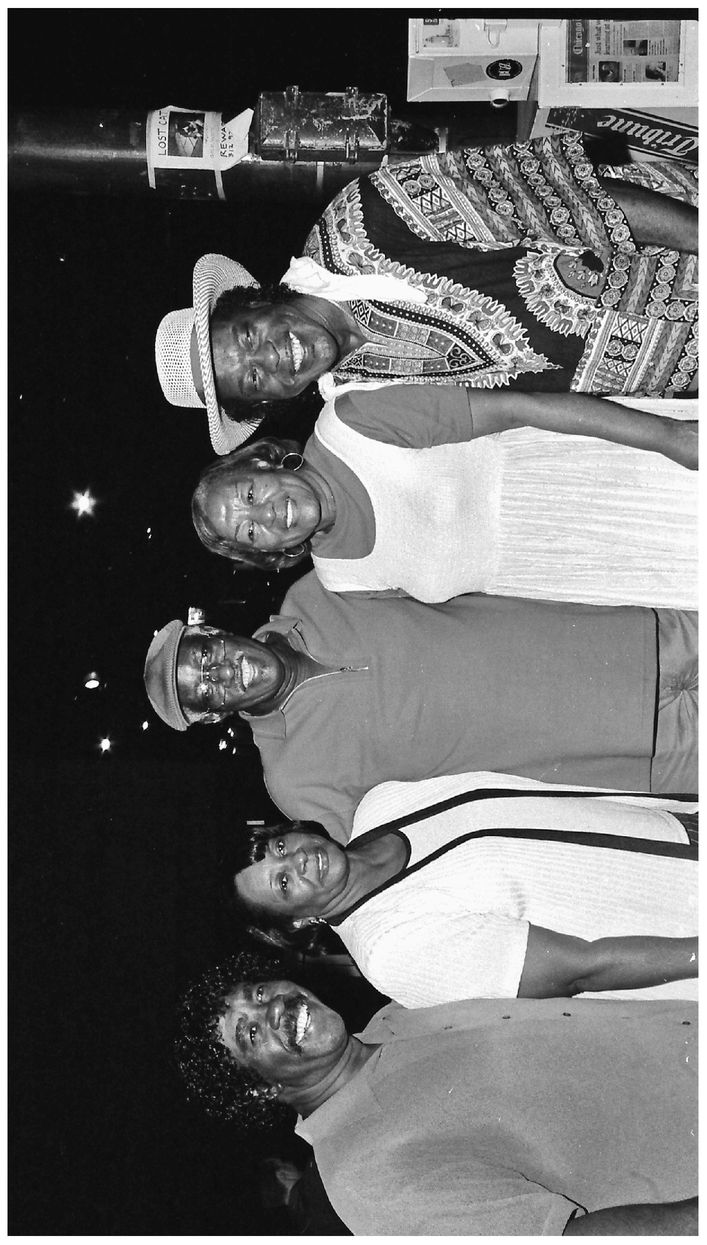

My loving family. From the left, my brother, Phil Guy, sister, Fannie Mae Guy, brother, Sam Guy, sister, Annie Mae Holmes, and I. Courtesy of Victoria Fudden

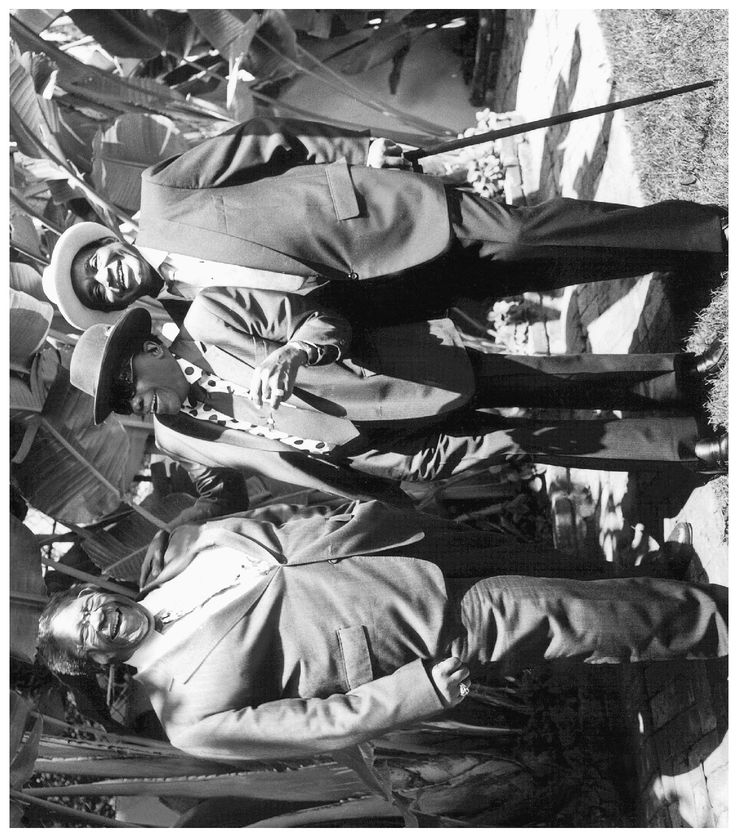

Teachers King, Hooker, Dixon.

Courtesy of Paul Natkin

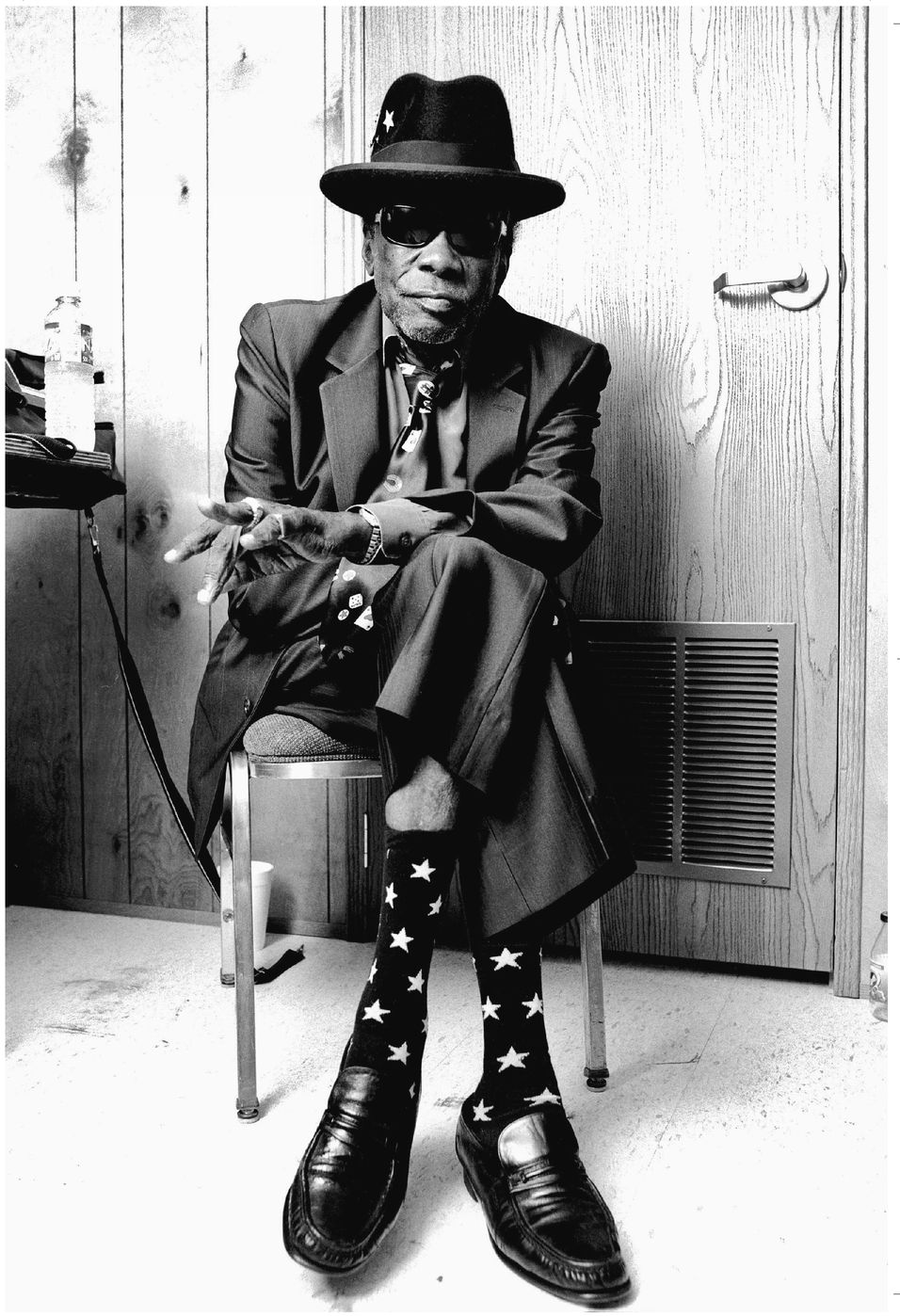

John Lee, the freest of all the blues poets. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

With Junior, brother for life. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

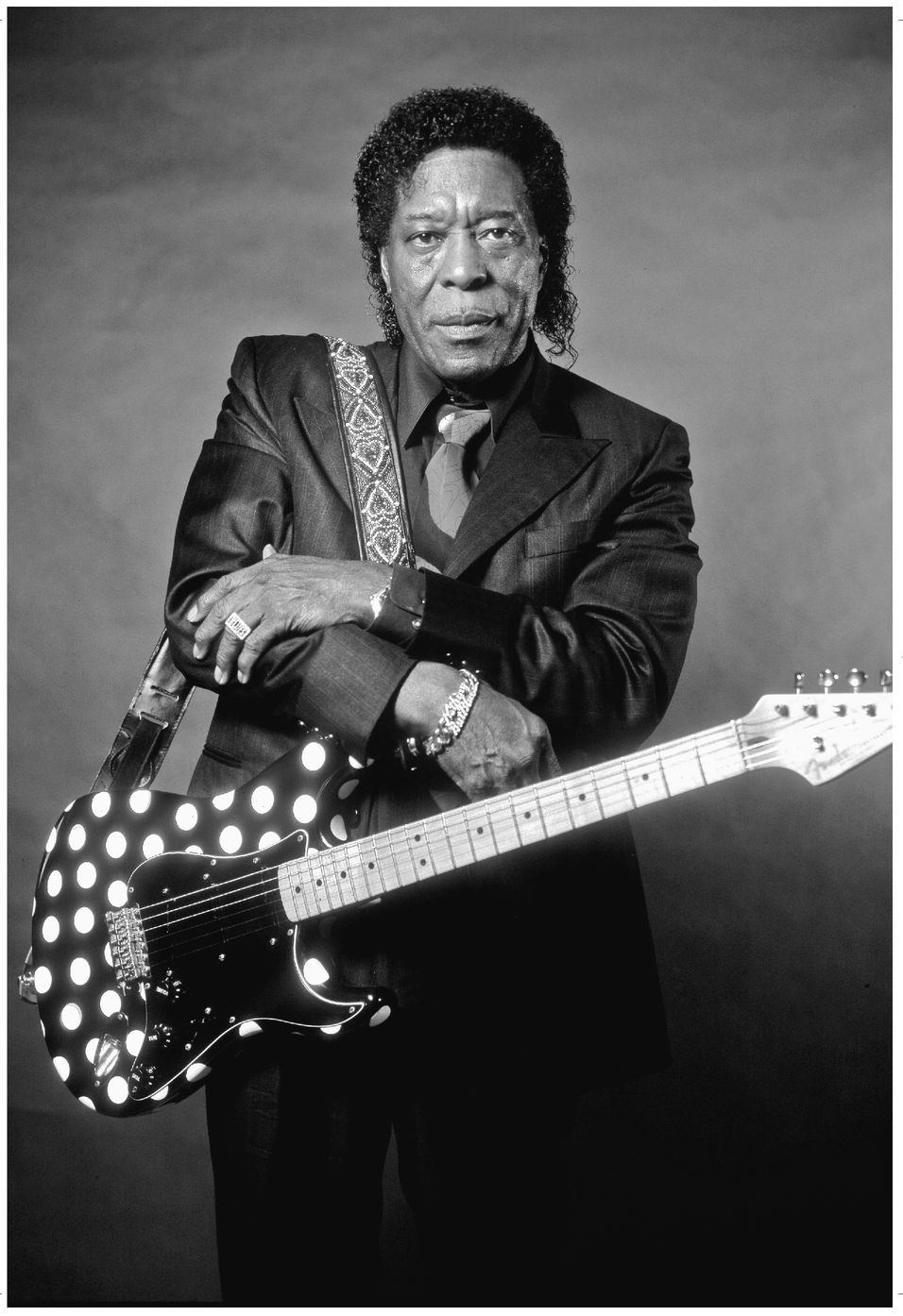

My jheri curl days. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

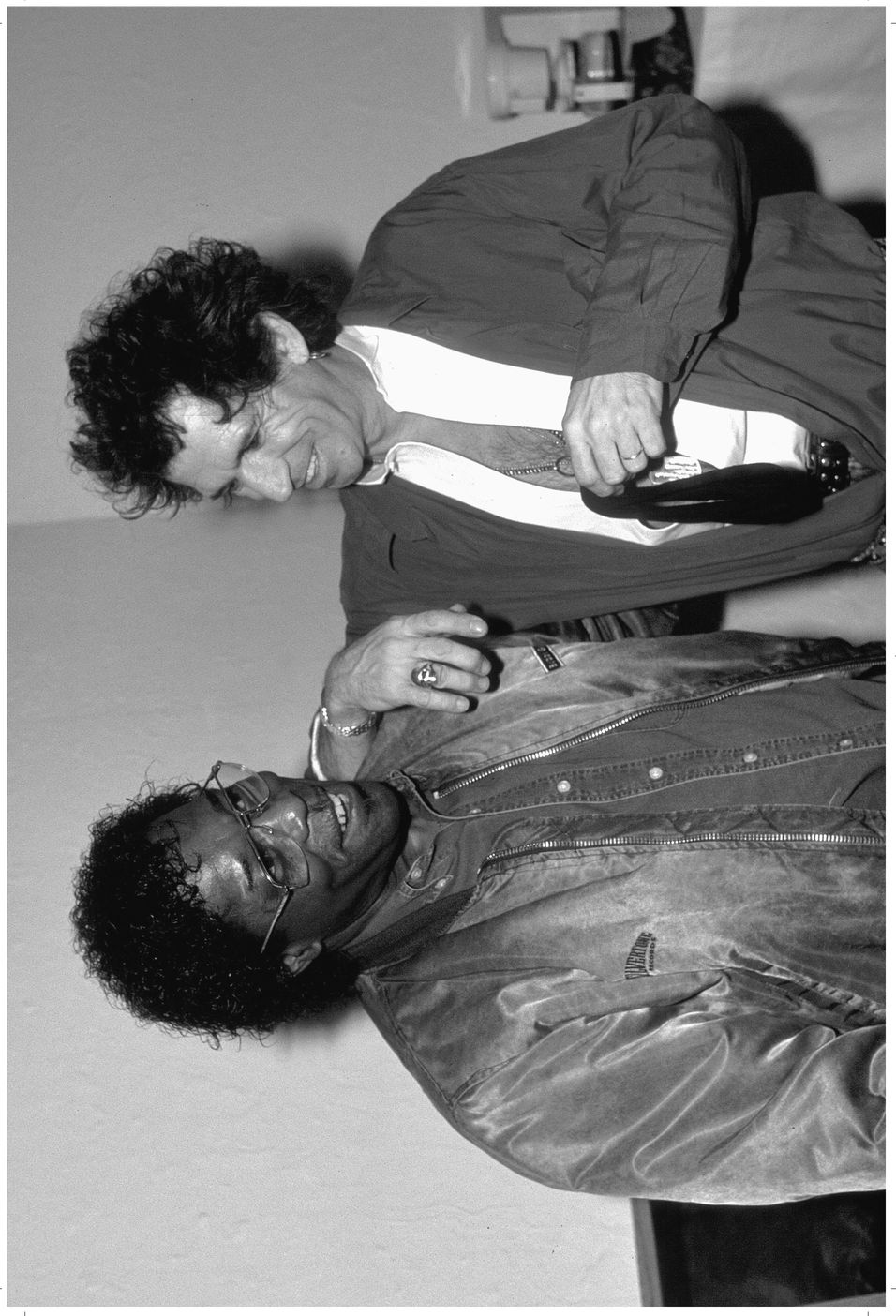

Eric Clapton, forever friend.

Courtesy of Paul Natkin

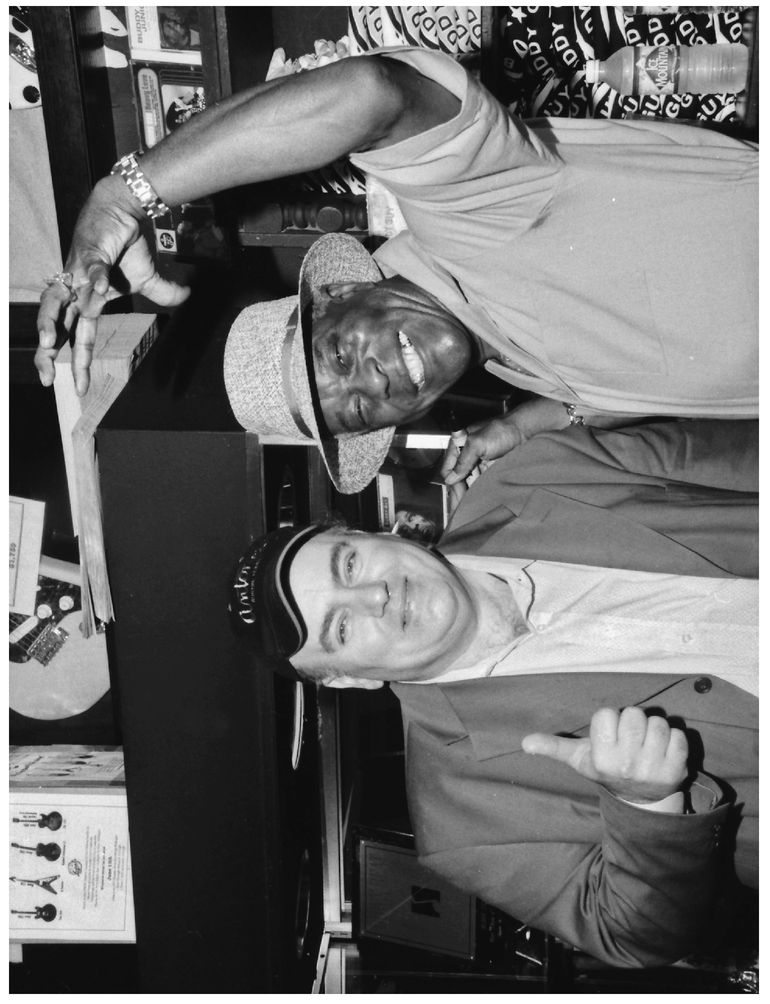

Keith Richards, loyal and true.

Courtesy of Paul Natkin

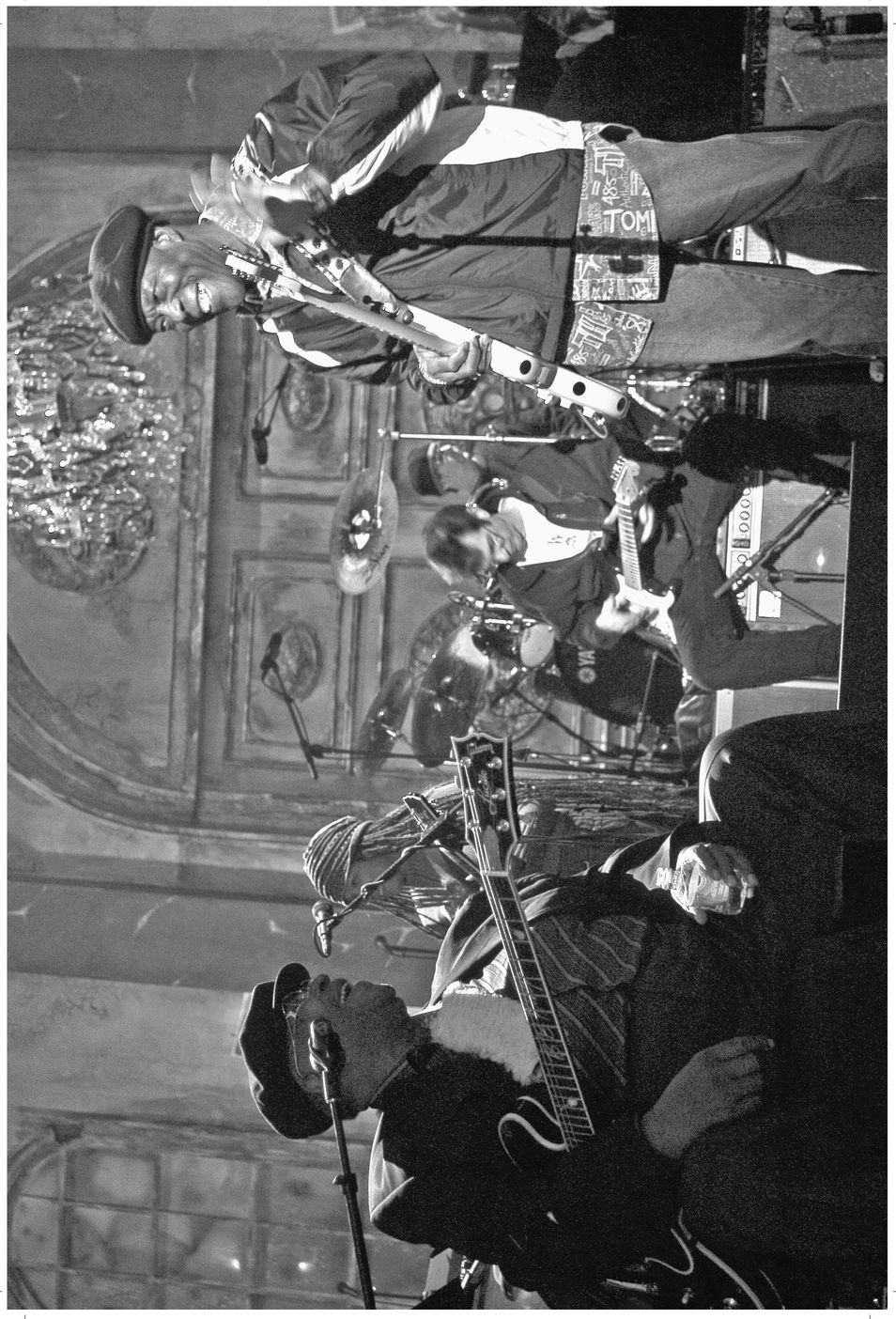

A man who made a difference: Clifford Antone. Courtesy of Victoria Fadden

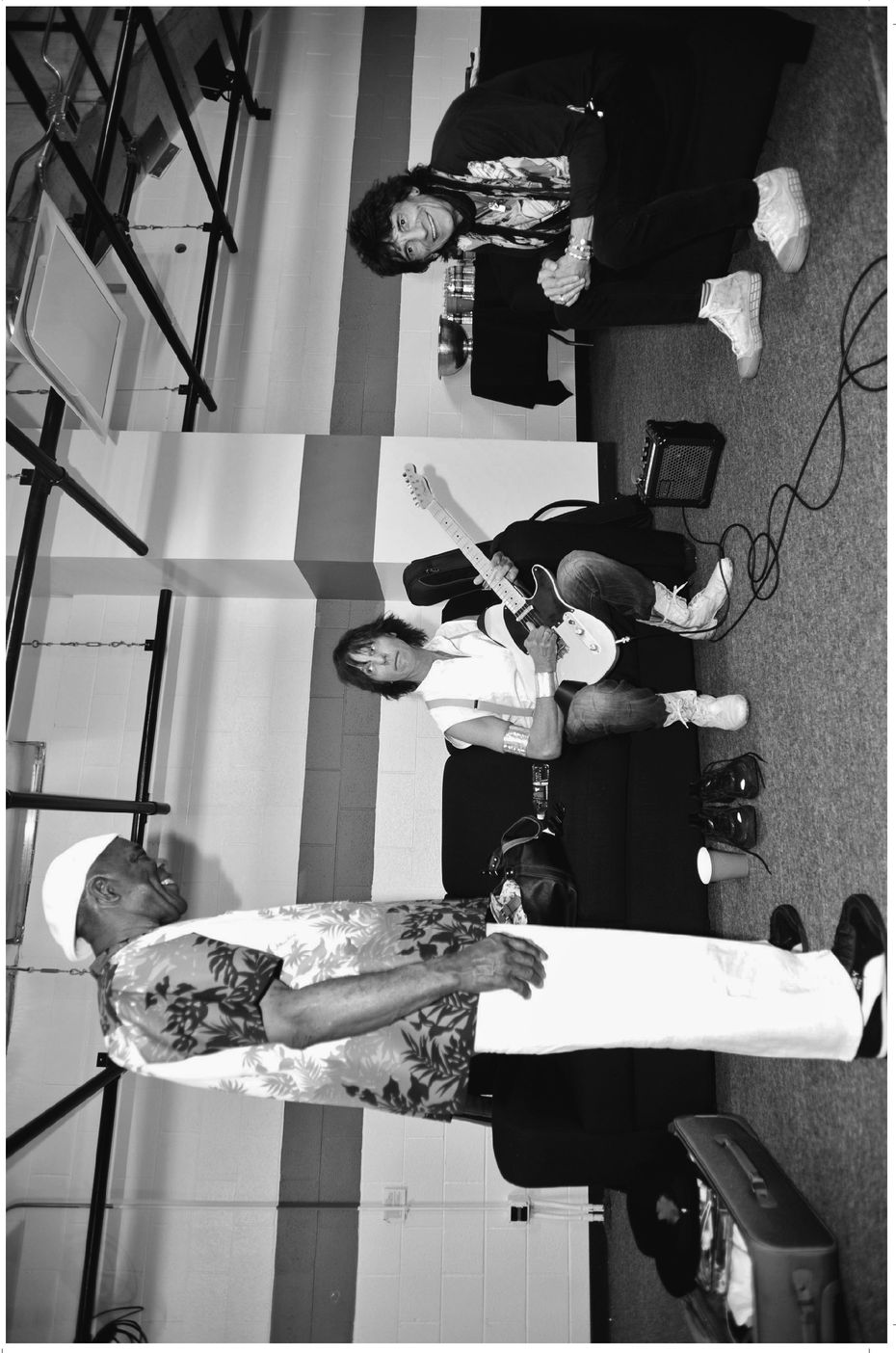

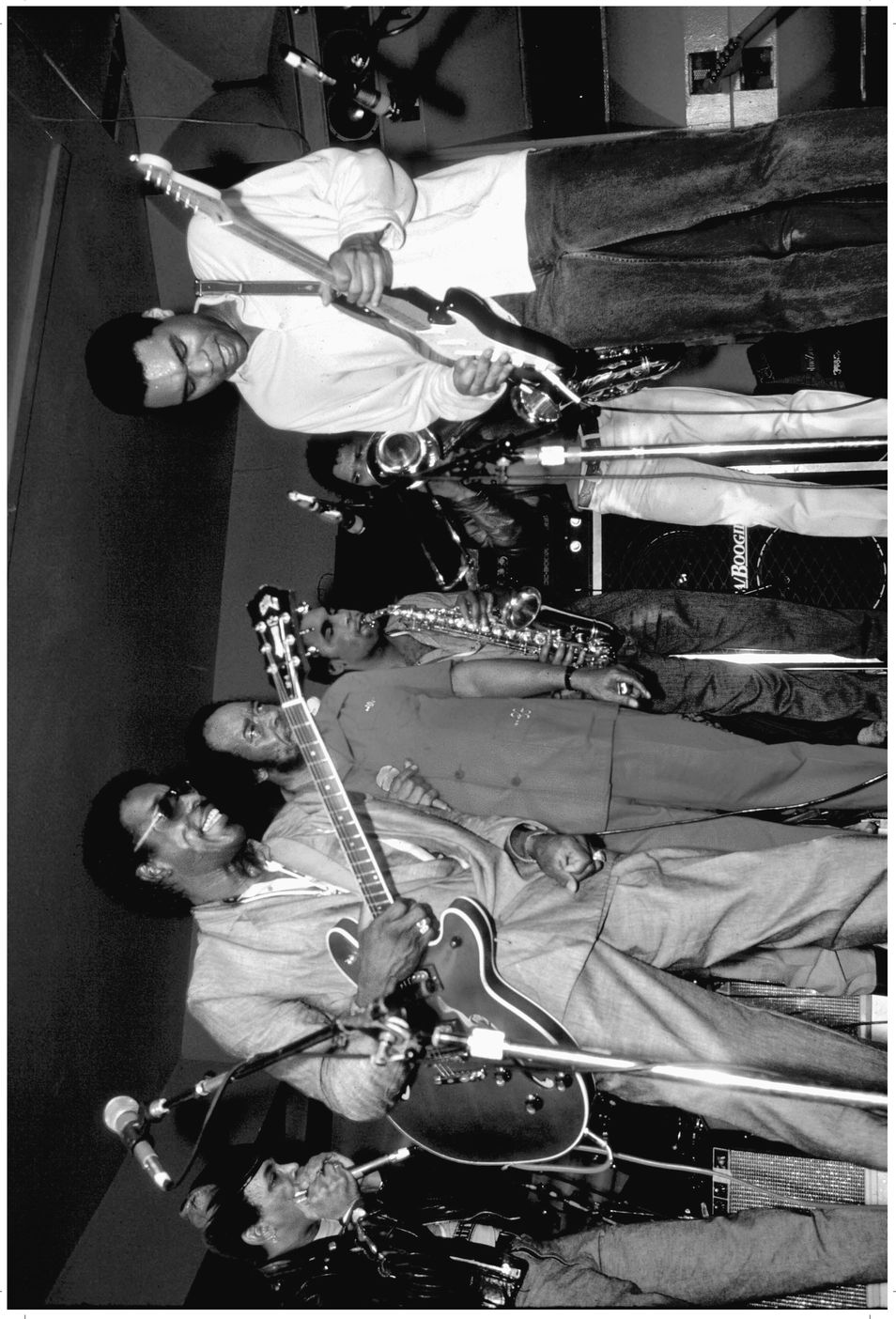

Jeff Beck and Ron Wood, fellow travelers. Courtesy of Paul Natkin.

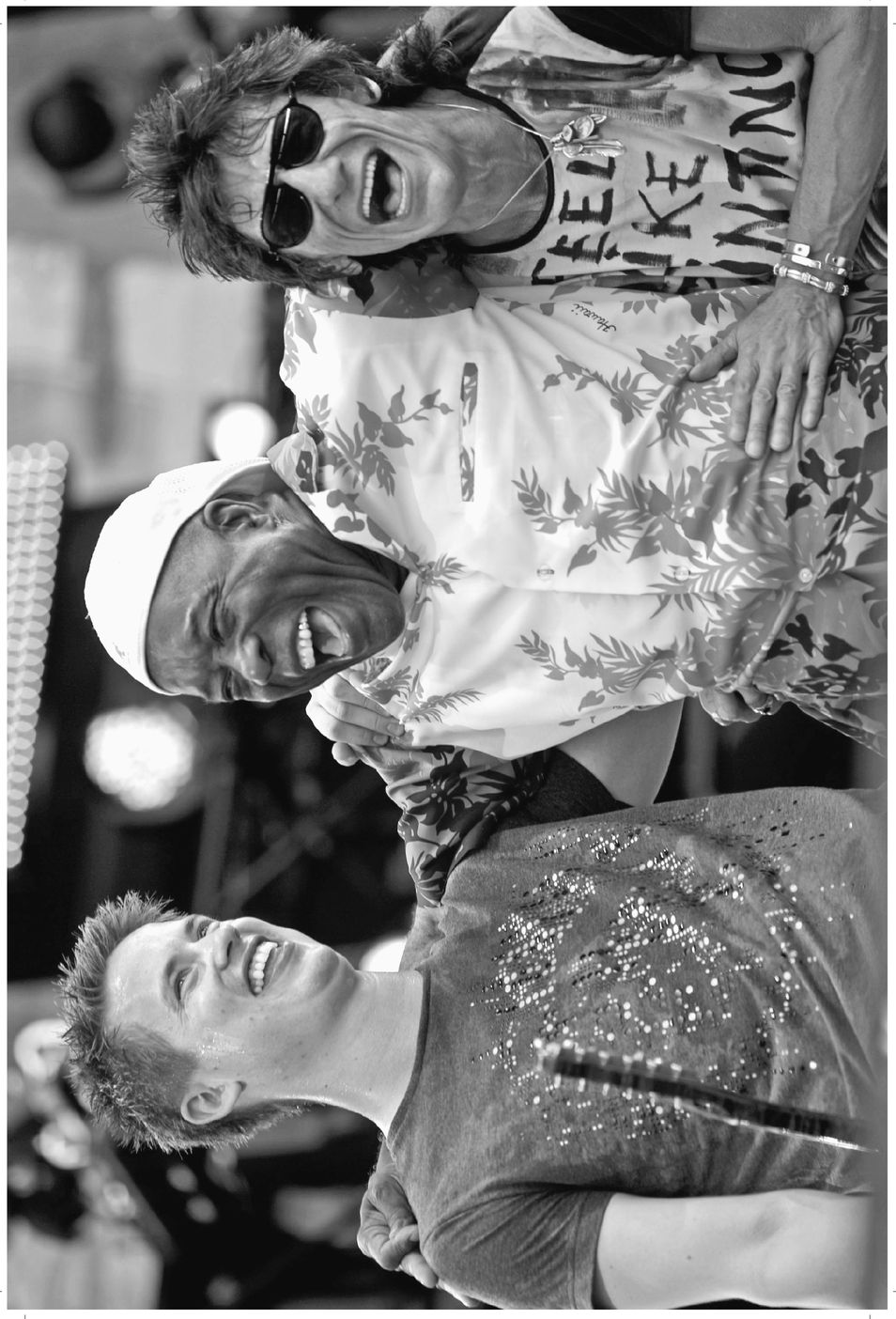

Generations converge, Jonny Lang and Ron Wood. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

Robert Cray helped boost the blues. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

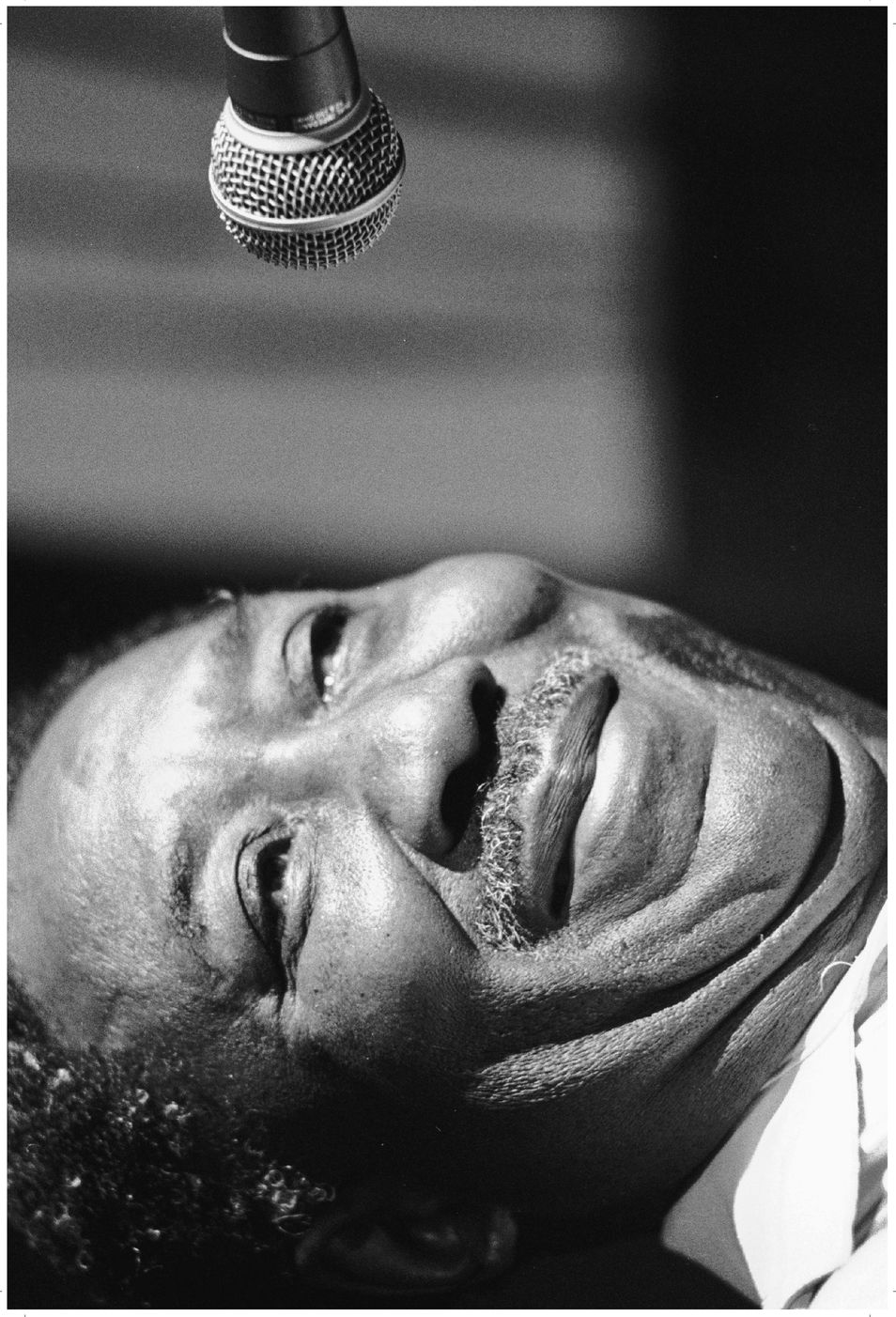

My best friend B.B. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

My latest and greatest club. Legends, 700 S. Wabash. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

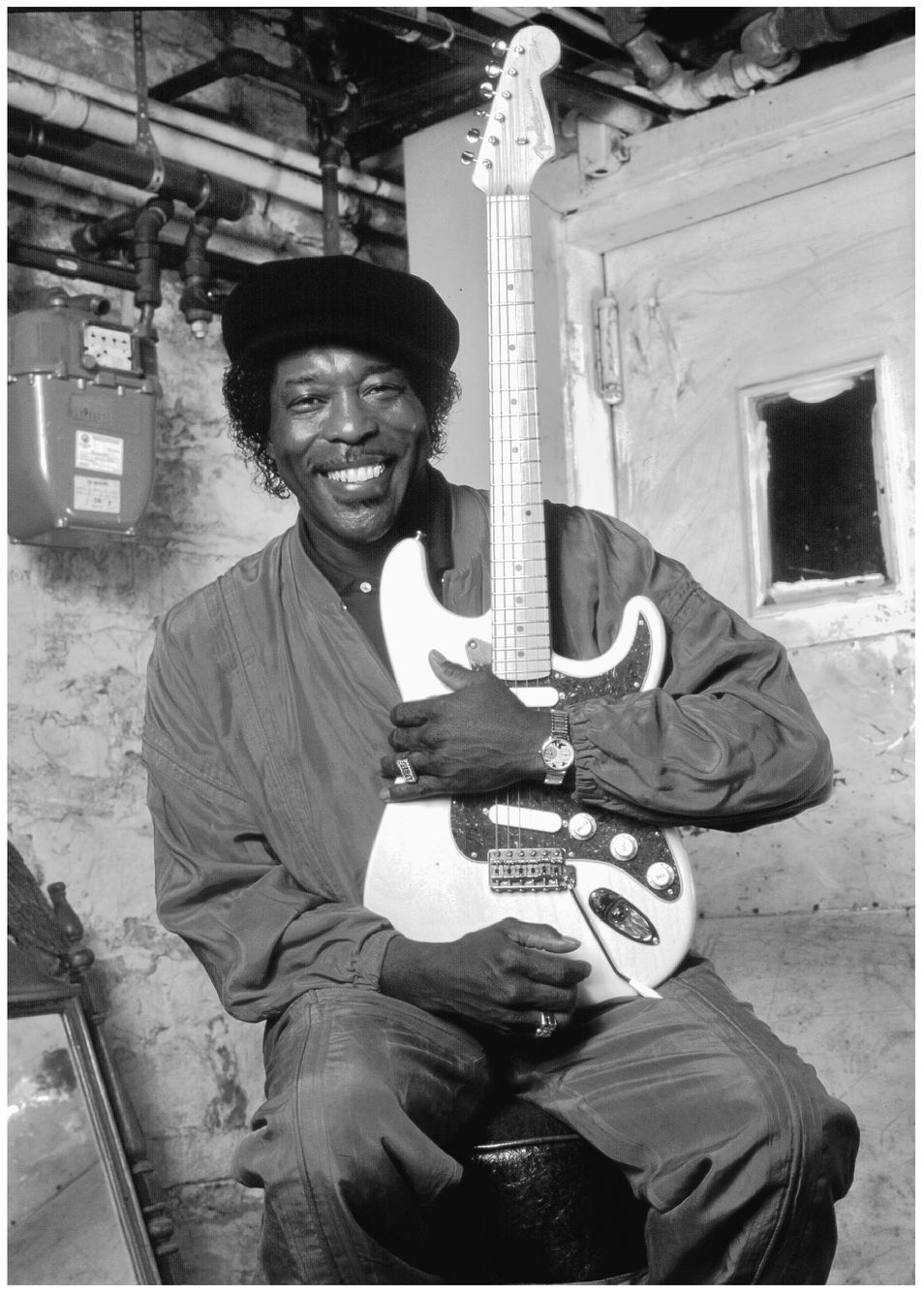

In the basement in my jumpsuit phase. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

Muddy, my main man. Courtesy of Paul Natkin

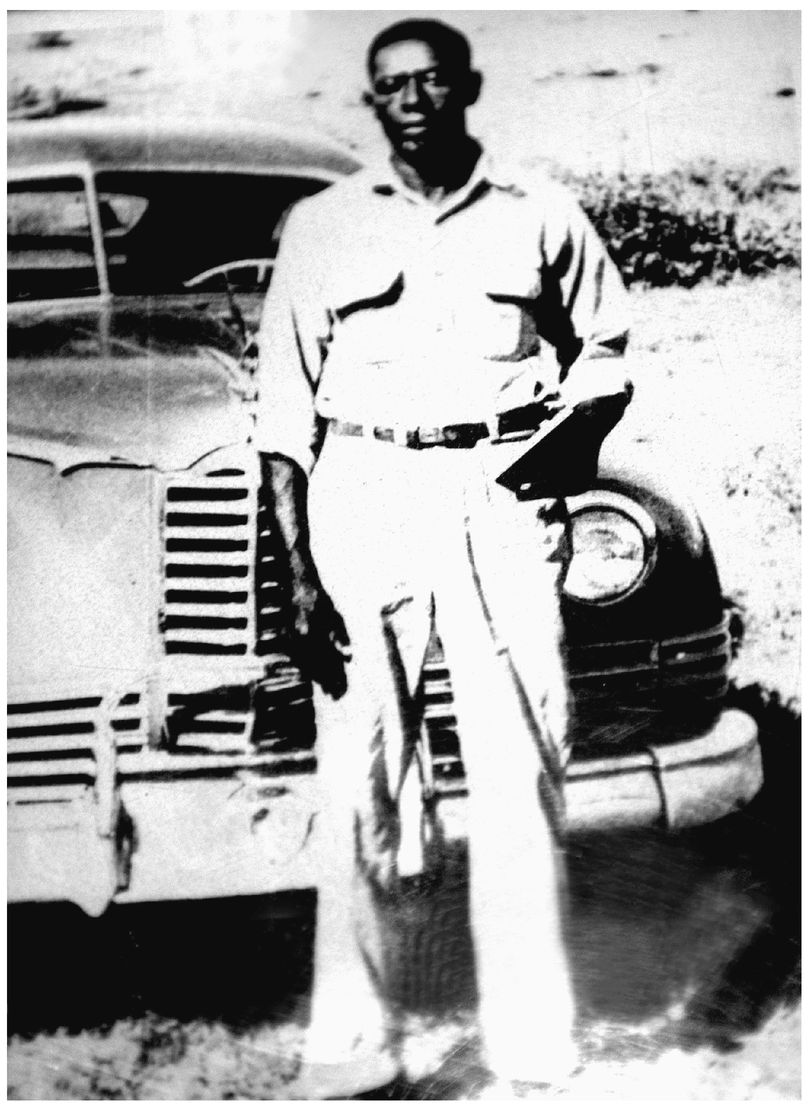

My beloved father. Courtesy of Paul Natkin