Gothic Cathedrals: A Guide to the History, Places, Art, and Symbolism (2015)

CHAPTER 7

BEJEWELED WONDERS IN STAINED GLASS

Lux Lucet in Tenebris: “Light shines in Darkness”

For hundreds of years, visitors have marvelled at the extraordinary beauty of the stained glass windows. People of “all faiths or none” often say that it is the huge medieval stained glass windows that affect them most when crossing the threshold into this new world of light. Stained glass was a dramatic change from what had come before in European architecture. Gothic architecture's chief artistic patron, Abbot Suger, surprised many when he insisted that he wanted to fill his new Abbey Church of St. Denis with “the most radiant windows,” those with far more luminosity than ever seen before. He wanted light—and the more of it, the better. Yet not everyone was pleased with this idea.

“this noble art has a hidden light...”

In fact, so enamoured was he at this idea, that he wrote about it extensively, even insisting that this verse be put over the door of his newly rebuilt Gothic abbey church (1140), the first Gothic building in medieval France:

Whoever you are, if you seek to fathom the good in these doors

Then marvel not at the gold or the cost, but find the aim of the artist.

This noble art has a hidden light that can lift the mind in an inward way

It warms the heart, to turn from daily concern to heaven within,

And opens the door to truth in each of us.

Such art can show how the spirit within can be found in this world:

The dull mind rises to truth through material things,

And seeing this light escapes its former submersion.

Notre Dame de Reims, exterior view, showing stained glass windows and its geometric stone tracery patterns. (Karen Ralls)

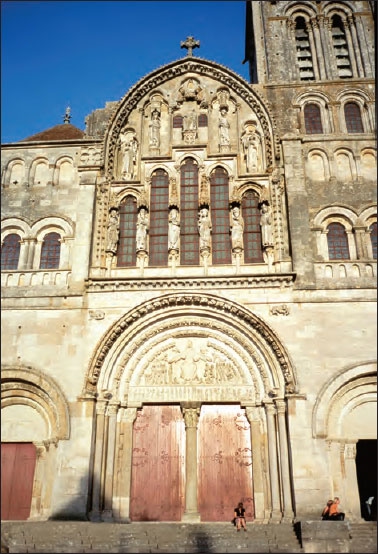

Vezelay, view of this majestic Basilica, one of the best examples to be seen today in France of the Romanesque style of cathedral architecture. (Jane May)

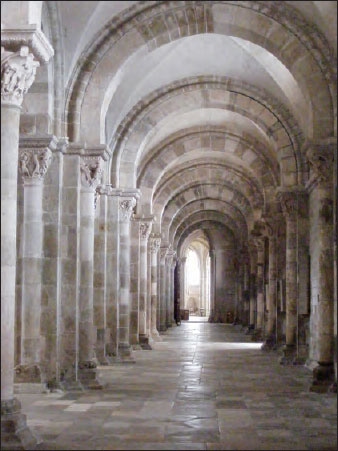

Nave, at the Romanesque Basilica of St. Marie Madeleine at Vezelay (Jane May)

Vezelay: tympanum and front door entrance. (Jane May)

The Romanesque basilica of St. Marie Madeleine at Vezelay, exterior view of its entrance. (Jane May)

So for the first time in Western history, in contrast to the dark, stunning, and somber Romanesque style with its cavernous passages and cloisters, Suger believed that with the new Gothic style, all who were in the building would feel uplifted and surrounded by light. With this new, revolutionary change, people were able to experience on a large scale the effects of direct, colored light in many hues, as opposed to the reflected light of paintings. This was a huge shift at the time, and a courageous decision that dismayed certain clergy. (1)

From Suger's inspired wish, the stone-masons were encouraged to create what became the now-famous “walls of glass” in the great cathedrals—literally, walls of brightly colored, gleaming stained glass. When looking at the stained glass windows in a Gothic cathedral's nave today, visitors experience a distinct feeling of being “pulled upwards” while surrounded by light all around them, permeating throughout the whole building. Some of the crypts of certain cathedrals have beautiful stained glass windows in them as well. The medieval designers of the cathedrals were well aware of, and highly valued, the effects of light.

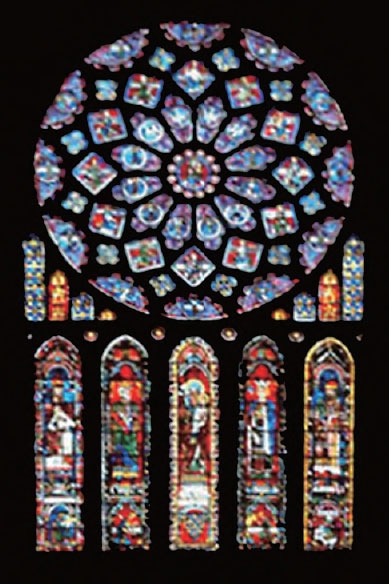

With the aid of the Gothic pointed arch and the flying buttresses to help support the structure of the building, cathedral walls were strengthened to such a degree that spaces could be cut away for large window casements, thus meeting the terms of Gothic's prime directive—more light. The great height of Gothic construction came when the architect, stonemason, blacksmith, and glazier would pool their resources together to create the luminous Rose windows, often dedicated to Our Lady, the exquisite stained glass windows of cathedrals at Chartres, Notre Dame de Paris, Reims, Sainte-Chappelle, and Salisbury, among others. One art expert commented that the cathedral can be imagined as a “city of light.” (2)

History of stained glass

The art of making stained glass windows is an ancient one. Although “stained glass” is what we call it today, the coloring of glass happened via other means than staining. The ancient Egyptians, for example, manufactured beautiful colored glass, while the Romans do not seem to have used translucent colored glass for windows. The mass manufacture of stained glass, as we know it today, began in western Europe in the ninth century. The practice of using lead strips to hold the pieces of glass together (“lead came”) seems to have originated in the Byzantine world. It is not known precisely when these two discoveries of coloring glass and binding the pieces together with lead took place, but the techniques were certainly well-developed by 1110-30, when the monk Theophilus wrote his famous Diversarium Artium Schedula. (3) Art historian and East-West expert Titus Burkhardt clarified the enormity of the European contribution to this art:

Exterior view: at Chartres stained glass factory, showing one work of its gifted glaziers. (Karen Ralls)

Exterior view of Salisbury Cathedral Cloisters in England. It houses one of the surviving remnants of the Magna Carta. (Karen Ralls)

In the Orient and Byzantium, as also in the Islamic world, where the art of the stained-glass window originated, it was the practice to set the individual pieces of stained glass in a frame made of hardened stucco. The use of lead moldings as settings seems to have originated in the Latin West; and it was this that for the first time made it possible for pieces of stained glass to be assembled, not merely in the form of ornamentation, but in the form of pictures. (4)

The twelfth century, complex techniques of stained glass manufacture had evolved has remained quite constant right up to the present day. Theophilus' book describes how to make a stained glass window. Colored glass, known as “metal” in those times, was made by adding various metallic oxides to the high temperature pot in which the glass was melted. Each metal oxide would give a different color: Cobalt produced blue; copper produced shades of green; iron produced red; manganese provided purple, and so on. The molten glass was then blown and shaped into sheets. Individual pieces were cut out with a diamond point. Details such as faces and draperies were added in black paint.

Beverley Minster north nave aisle showing tracery patterns. (Karen Ralls)

In the 14th century, a silver compound was discovered, which, when added to glass and fired, produced lovely oranges and yellows, colors that were perfect for details like a halo or hair. (5) Even for experienced glassmakers or “glaziers,” all of this was a careful procedure that involved constant trial and error as to exactly how the colors in each sheet of glass would turn out.

Natural pot-metal glass was too dark to really let in much light. In order to effectively solve this problem, the medieval glaziers invented a technique of applying or “flashing” a thin layer of the colored glass on to a sheet of white glass. The detailed design for the window was drawn at full scale onto a whitened flat wooden table, and the panes of glass were cut to the correct shapes to fit into the pattern.

Theophilus not only talks about how to make stained glass, he also describes how the glass painter made his painting. Rather than creating a “cartoon” outline,* of the full-scale work, a medieval stained glass artist would instead draw with charcoal the full-scale picture on a wooden trestle table coated with chalk or whitewash. The drawing was then marked with symbols or letters to indicate the individual pieces of glass that would be used to change the color. This master drawing served as a guide for the glass-cutter and the painter, and it also doubled as a workbench for the assembly and leading-up of the entire window.

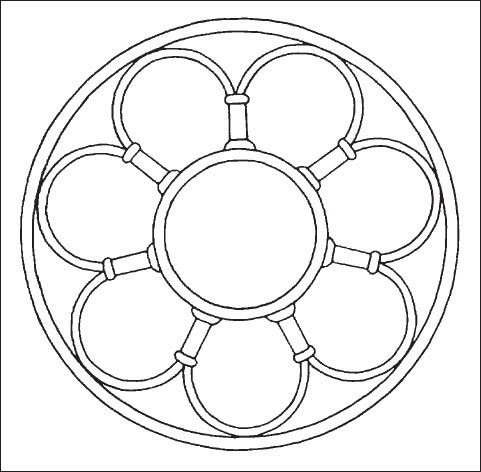

Simple illustration of the seven-petalled stonework tracery pattern used in some stained glass windows, often associated with Sophia wisdom. (WMC)

This whitewash table was inexpensive and relatively easy to use, although it wasn't readily portable or very easy to store. A medieval stained glass design would often be used more than once and so was viewed as a practical working tool. Most of the time, the glass painter was also the designer of the window, although in some cases the patron would supply the artist with sketches from which to work.

The stonework geometrical designs around many sections of a stained glass window are called tracery—a geometrically-shaped building ornament “to divide the arch bay (couronnement) above the impost line from windows; later, also to articulate wall surfaces and for parapets.” (6) Many of the now-famous Rose windows feature intricately carved stone tracery designs around the stained glass windows. The basic forms are the foil and the triskele, often used in groups (trefoil, quatrefoil, etc). Such careful attention to the order of the cosmos when building these buildings is reminiscent of the Wisdom of Solomon 11:20, where it is stated that God had “ordered all things in measure and number and weight.” (7) When the new Gothic style added light to its architectural aesthetics, it became a heady combination.

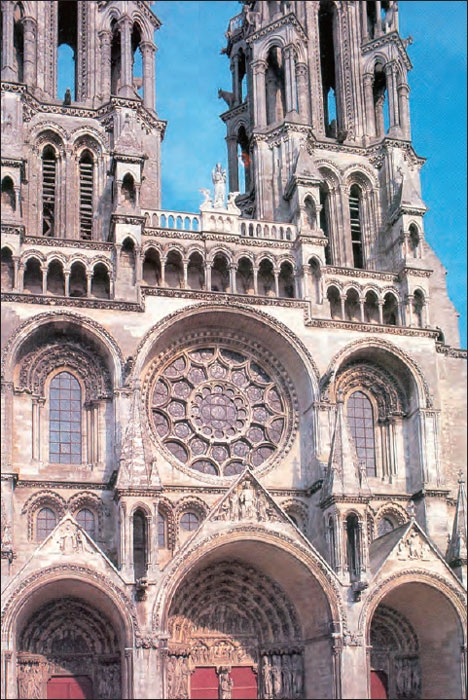

Laon, The Cathedral of Notre Dame de Laon in northern France. (Mr A Sbestt, WMC)

The Stonegate Red Devil, York, England. In the 16th century, the Stonegate area of York became famous for its book shops and printers. During the Middle Ages, this street fell under the jurisdiction of York Minster and was home to many guild craftsmen, including glaziers. A number of glass painters were also known to have had their workshops here. The “Red Devil” outside of No. 33 is a traditional symbol of a printer. (Simon Brighton)

A masterpiece of French Early Gothic, started in the 1150s, the majestic cathedral of Notre Dame at Laon (northern Champagne) is a case in point. Perched high on an imposing hilltop, it clearly defines the skyline with its five massive towers; its huge Rose window was the first major Rose windows created after the first Gothic building, Saint-Denis. (8) Laon, a Merovingian site, was also the center of the earlier Carolingian empire in France. Its cathedral dominated Gothic architecture in northern France for decades until the creation of Reims cathedral in the thirteenth century. There is an interesting museum focusing on the cathedral and town next to the cathedral, with a fascinating medieval Templar museum nearby—not to be missed.

At Wells cathedral, in the earliest surviving glass, we have colored bosses with some of the earliest examples of natural themes—featuring flower motifs painted with ivy leaves, for instance—and in the chapter-house itself, the trefoils of the tracery above still have the intricately carved vine leaves on them. (9)

The oldest surviving medieval stained glass windows date from about 1065, in the cathedral at Augsburg, Germany. By 1355, glaziers in Italy were officially using “cartoons” rather than whitewash tables to represent the full-scale models of the stained glass windows. Since paper was more readily available in Italy than in the rest of Europe (thanks to the papermaking guilds), the procedure was not widely used elsewhere until the early sixteenth century. Similar techniques are still used today. The art of making stained glass windows declined until the time of the Victorians in the nineteenth century, when they revived the medieval techniques.

Some today believe that alchemical methods of glassmaking originated in the ancient world—no surprises there—and, possibly from certain Persian alchemical processes. The exact formulas for a few of the colors in the medieval stained glass windows are to this day, difficult if not impossible, for modern scientists to precisely replicate. But no matter where the original techniques came from, the effects of certain colors—especially the luminescent cobalt blue at Chartres, for example—are extraordinary.

There is no question that the bright colors and light from these skillfully-crafted stained glass windows are a marvel to behold. Abbot Suger was enraptured by the light-mysticism of Dionysius. (10) So dedicated an artistic patron was he, that he ensured that only the very best sapphire glass was found for the windows of Saint-Denis. He also made the effort to appoint a specialist craftsman to keep these blue treasures of light in good repair. (11) The windows of Chartres seem to showcase Suger's most important theological themes, such as the Coronation of the Virgin.

If you make stained glass art, or have ever visited a modern stained glass studio, the process is much the same as it was in medieval times—the artist cuts the glass and solders it together. The stained glass tradition continues, in Britain, France, and in many other countries all over the world. In England, there are beautiful cathedrals and glass museums to visit, such as Ely and Canterbury. Some people enjoy visiting the Stonegate area near York Minster, where, in medieval times, the glass artisans, glaziers, printers, and other skilled craftsmen worked. Today, the “Stone-gate Devil” symbol is a landmark in the area; it was a 16th century emblem for a printer's premises and, although not from the medieval period, per se, it is a fascinating area of York to visit.

And in the town of Chartres, the International Center of Stained Glass is a fine museum to visit; you can still see the artisans at work in their studio spaces. One of the stained glass artists there said, in jest, “Shame there are no wine glasses here now, though.” Curious, I asked him what he meant. He said that this particular site is located on the very same spot that housed the twelfth century half-timbered tithe barn, in which the medieval bishop of Chartres would receive his subjects' ten percent tax of grain and wine!

Temple Rothley, modern-day example of a medieval Knight Templar depicted in stained glass. (Karen Ralls)

Wisdom in light: symbolism of stained glass windows

When stained glass windows first starting appearing in more cathedrals, churches, and other Gothic buildings, some of the more conservative clergy seriously questioned whether it was a good thing that “so much light” should be let in to the church. Today we would say that the windows simply speak for themselves; they ultimately need no official interpretation at all; each person experiences them in his or her own way. Perhaps, those medieval clergy would marvel at the words of renowned modern Art History professor Michael Camille of the University of Chicago; he described the experience of crossing the threshold into Chartres as, “entering the celestial city of Chartres cathedral,” so transporting is the impact of its beauty, including its famed stained glass windows. (12) Fortunately, many in medieval times also greatly appreciated these newly illuminated buildings. Those who objected to this design innovation were outnumbered, and the enduring legacy of these bejeweled wonders is still with us today.

Interior of Chartres cathedral, showing various side chapel's stained glass panels as you walk around the choir area. (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

Chartres cathedral, North Rose window. Its geometric spiral design incorporates what many believe to be knowledge of the Golden Mean. (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

As one might imagine, a great variety of spiritually-themed visual images form the main content of the imagery on the stained glass windows: apocryphal texts; allegorical imagery of biblical stories and characters; various Pagan and Christian imagery portraying people, beasts, and plants; portraits of saints; as well as depictions of celestial phenomena such as the sun, moon, stars, planets, angels, and demons. The variety is endless, depending on the theme of the window in question, its sponsors, and focus.

King David playing the harp, Winchester cathedral (Karen Ralls)

As we have mentioned, some of the most stunning medieval stained glass to be seen today is at Chartres. What is interesting about Chartres is the great number of members of the whole community who helped support, build, and fund it. Of the 186 window designs in Chartres, 152 can still be seen today. Art historian Hans Jantzen comments that, “records survive of those destroyed between the eleventh and eighteenth centuries. All of these windows were endowed individually, and since the benefactors are identifiable by inscriptions, we are able to trace the part played by the whole population” in the building of this great cathedral.

Members of the French royal house endowed stained glass windows, of course, and other nobles and clergy. But it is the rather long list of various guilds that is interesting to behold—gifted craftsmen (and women) all. Here we have clear evidence of support from the skilled guilds of bakers, butchers, clothiers, glaziers, tanners, carpenters, vintners, spicers, smiths, joiners, coopers, masons, shoemakers, weavers, pastry-makers, innkeepers and others. (13) As all of these guilds are recorded as benefactors by the portrayal of their professional activities (on the lowest window panels), we also discover what was considered typical of the crafts and trades at the time.

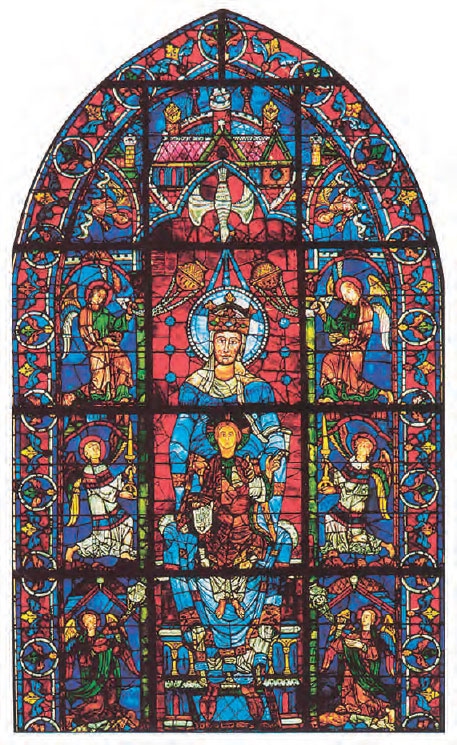

Blue Virgin Window at Chartres Cathedral. (Karen Ralls)

Above the Royal Portal sculpture are three windows, dating from about 1150, among the oldest and most luminous to have still survived. Both in design and in meaning, these three windows form what is called a triptych, and have images that proclaim various prophecies. The “Tree of Jesse” theme probably first took form in stained glass around 1144, in a window at the royal abbey of Saint-Denis, before spreading out elsewhere to become one of the most popular subjects in medieval iconography.

Other major themes of windows at Chartres include angels, the signs of the zodiac, sun, moon, stars, plants, beasts, the Incarnation, Passion, Resurrection, the famous Blue Virgin window, Joseph, Noah, St. John the Divine, Mary Magdalene, The Virgin Mary, the parable of the Prodigal Son, the Good Samaritan, Adam and Eve, and so on. One of the most extraordinary windows, in terms of beauty and its effect on modern-day visitors, is the famous Rose Window in the north transept, built according to the principles of sacred geometry, number, and proportion. The dimensions of the Rose window “are echoed in a tiled labyrinth on the floor of the nave.” (14) Music, too—as one of the seven liberal arts—would often be incorporated into a stained window's design, such as the lovely windows featuring King David playing the harp at Chartres and at Winchester cathedrals.

Certainly, one of the largest and most dramatic stained glass window panels at Chartres is the huge, imposing thirteenth century Blue Virgin Window in the south ambulatory area. (15) As many note, “you just can't miss it,” so bright are the blues and reds in the stained glass itself, let alone the overall design. These four panels are wonderful examples of medieval glass art. Mary is represented as seated, facing the viewer, crowned on her celestial throne with the child Jesus on her knee. Her halo and clothing are of a stunningly luminescent cobalt blue, set against a rich ruby background—the effects of which seem to shift and change as the angle of the sunlight coming into the cathedral over the course of a day shifts. She is surrounded by angels, with brightly colored sashes and censors. Beneath her throne, as English-speaking expert guide and British author Malcolm Miller explains, six panels narrate the stories of her Son's first miracle, the changing of water into wine at the marriage feast of Cana. At the bottom of this window, are shown the three temptations. (16)

In the next chapter we will explore the equally intricate stone and wood carvings of Chartres, produced by some of the best medieval guild craftsmen of the day. The labyrinth and stained glass windows that we have discussed at Chartres are essential to spiritual balance. They interrelate in the tapestry of meaning that envelopes the entire building:

And here lies a key to understanding the power of Chartres to stir the soul. Not only are Pagan and pre-Christian elements united in the building, but so too are the qualities of light, height and extension traditionally ascribed to the Masculine, or God, balanced and harmonized with the qualities of darkness, depth and inwardness traditionally ascribed to the Feminine, or Goddess. The labyrinth draws us to the center as a place of the marriage of these two principles. (17)

Stained Glass Window at Leeds Theosophical Society, England; this lovely geometric glass design is a part of the front window of its wood-panelled lodge room (Paul Barker)

Zodiacal Stained Glass windows roundels at the Leeds Theosophical Society, Leeds, England (Paul Barker)

St. Giles cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland; an exterior view of its stained glass windows from its famous cobbled High Street, The Royal Mile. (Karen Ralls)

Surviving medieval stained glass today

The ancient stained glass of Canterbury Cathedral is certainly “one of the glories of medieval English art.” (18) It is one of the few English cathedrals to still contain any considerable amount of twelfth century stained glass, and should also be visited along with the great French Gothic cathedrals like Chartres, Notre Dame de Paris, Sens, Noyon, and others. Visual imagery in the windows here abound with the usual saints and angels, but there is also more unusual symbolism. This includes a flock of crows, horses grazing, a ploughed field with thorns, a net with fish, wine and beer glasses, foods, and a sundial. (19) The same architect, the renowned medieval French Master Mason William of Sens, was chosen to rebuild the choir at Canterbury after its devastating fire in 1174. It was a great honor at the time to have him agree to this job; the earliest windows were probably finished by 1184.

England also has such treasures as Salisbury cathedral, Durham, York, Winchester, Gloucester, and others. Each has fabulous stained glass windows that are witnesses to great talent and history. Other private chapels, charitable organizations, civic buildings, guildhalls, and so on, have stunning examples that have survived into the present day.

Imagery—not mere words—conveys the ultimate meaning:

In the thirteenth century, Thierry, the Chancellor of the School of Chartres, wrote that the stained glass windows were to teach those who were illiterate, as most people were in medieval times. Today, however, we are increasingly realizing again that “a picture is worth a thousand words”—and then some—in our digital age. The power and beauty of visual images and pictures, not mere words, have a much greater power to convey the spiritual meaning the artist intends to communicate. The internet has also shown us in many cases that this is true. People absorb stories in their own personal and intuitive way. Thierry went on to say that the “paintings in the Church are writings for the instruction of those who cannot read ... The paintings on the windows are Divine writings, for they direct the light of the true sun, that is to say God, into the interior of the Church, that is to say, the hearts of the faithful, thus illuminating them.” (20)

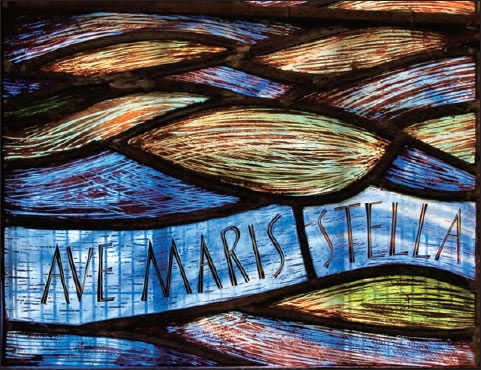

Ave Maris Stella - contemporary example of mermaids depicted in a stained glass window in Lincolnshire church. (Simon Brighton)

To medieval viewers of the stained glass windows, most of the themes, stories, and legends portrayed would have been second nature. We all “see” and experience the imagery in a medieval building in our own unique way, then as now, making any one definitive interpretation nearly impossible. In the High Middle Ages, the stories of the miracles of the saints from local as well as biblical and other lore would have been much more innately familiar to visitors than they are today, in spite our much-touted widespread literacy. Following the narrative can also be more difficult for modern-day viewers because medieval stained glass designers did not always arrange the sequences in a strict and logical sequential order—for example, many windows start at the bottom and work their way through the narrative to the top—just the opposite of what we would expect.

There are other sources of confusion for modern viewers. The easily-viewed bottom frames of stained glass windows were often deliberately saved for special scenes depicting the donors of that particular window. It is thanks to this custom that we know which guilds helped to sponsor specific windows. Some windows also show the major scenes in the central medallions and provide commentary along the sides. At other times, the panels were accidentally scrambled during restoration, and put back out of chronological order.

As some art historians have regrettably noted, people today have lost the ability to fully “read” symbols—to sense the meaning behind the stories displayed in the stained glass windows and stone carvings of the cathedrals. The imagination was highly valued in medieval times, and has gradually become less so for a growing number of people. As poets, artists and some scientists remind us today, it is essential that we work to reclaim and re-acknowledge that ability—now more than ever. Environmentalist John Muir, a Scot, who spent much of his life in the USA and was instrumental in helping to save Yosemite, famously declared: “The power of imagination makes us infinite.” Yeats, Coleridge, and others would certainly agree.

In a sense then, although our modern culture is far more literate than the medieval period ever was for the populace, it is we who are now more visually illiterate. It is we who have largely forgotten how important the world of knowing and experiencing a symbol was in medieval times. The emphasis in modern times has been almost exclusively on the written word, and, in doing so, much was lost in the process. As one commentator so aptly pointed out, in relation to his reflections on the late medieval Rosslyn Chapel, begun in 1446:

History can more accurately be found in the face of the land, in the faces of the people we meet, in the languages we speak, in our customs and traditions ... (21)

In the High Middle Ages the printed word was not the primary way history was understood or transmitted, or the meaning of symbolism communicated. In fact, visual imagery and pictures were often treasured far more than words, and seen as a more effective way of reaching people at a deeper level of awareness—secular or sacred. Writings were largely available only to a few—the privileged few who could read or write, mainly the higher levels of the clergy.

The skilled craftsmen who built these extraordinary buildings, and the learned ones who sponsored and assisted them, have left us silent images to ponder—visual symbols—to be interpreted not from the head, but also, from the heart. Perhaps, in doing so, they have also left us the tools to help us reclaim such neglected abilities again, bringing back a far greater appreciation for the Imagination and inspiration in daily life.

To the medieval viewer, Gothic light was not merely seen as a “natural” light; its “unnaturalness,” when experienced in conjunction with the inspiring power of the architecture, was perceived as a “supernatural” light.” The Gothic interior “is enveloped in a dark, reddish violet light, which has a mysterious quality difficult to describe... the ‘unnatural’ Gothic light confronts us also with a pictorial world of the richest imagery, its silent power exercising enormous influence over mankind.” (22)

Modern culture teaches children to be “afraid of the dark,” when, in fact, in earlier times, the great wisdom of the dark was valued far more. The darkness of the sanctuary and crypt at Chartres, for instance, still has the power to illuminate and evoke via what some call a “jeweled darkness.” (23) A key part of this effect, of course, are the stained glass windows, which allow an infusion of continuous light amidst an often-dark cathedral nave,transforming the soul, according to poets, dreamers, and many visitors today. We are here reminded of a phrase from a poem by T S. Eliot; “...So the darkness shall be the light...” (24)

No ordinary light indeed, and also a reflection of the possibility for inner illumination, higher wisdom, and truth. Such connections are available to anyone in the world, who can visit and appreciate the beauty of a Gothic building—whether that person is spiritually-inclined or not. The cathedrals offer modern visitors the opportunity to re-experience what Abbot Suger's original vision was for the new Gothic style: “Brightly shines that which multiples brightness; and bright is the noble work through which the new light shines.” (25)

All who see these windows have their own perspective. Some people have said that when returning to see the stained glass windows—sometimes even years later—they experience them differ-ently—perhaps all the more revealing—as it is the images, colors, and shapes themselves that can reach us at the deepest levels. In the High Middle Ages, they also provided an environment for medieval drama, pageants, feasts, and the music of the troubadours to flourish. (26) Again, the Imagination reigns supreme, as does the light. In the immortal words of the English poet William Blake:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

—William Blake 1757-1827 (“Auguries of Innocence”) (27)

Yet these beautiful windows are not alone in a Gothic environment. They are often most in immediate proximity to many stunning, intricate stone carvings and enchanting wood sculptures—marvels to which we will now turn.

*“Cartoon” is a stained glass term referring to the line drawing used in the creation of the design of the window.