Gothic Cathedrals: A Guide to the History, Places, Art, and Symbolism (2015)

CHAPTER 10

“FOR PILGRIMS ARE WE ALL”

The Decline of Pilgrimage and Visiting Gothic Cathedrals Today

They say all great things must end and that historical cycles come and go. These are among the great lessons of the cycles of history. In order to more fully examine the inevitable decline of the great era of medieval pilgrimage, let us first have a look at its peak period—the latter part of the twelfth century and throughout the thirteenth—to better understand how and why a decline later took place. A decline that would change the Church and western Europe forever.

Readers may wonder what medieval pilgrims would actually encounter along the way, and once they reached their final destination. So much strenuous effort had been expended, so much time and energy invested. We are here reminded of the now-famous quote by Robert Louis Stevenson: “To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive, and the true success is to labor.” (1) To maintain the eternal hope of finally getting to one's final destination safely was every medieval pilgrim's wish. This was as true in the Middle Ages as it was in Stevenson's time, as it is for many today.

WHAT HAPPENED ONCE YOU FINALLY GOT TO YOUR PILGRIMAGE DESTINATION?

Getting through customs and entry: the first step

Have you ever had to endure standing in a particularly long queue for hours, waiting to get through customs? Well, so did medieval pilgrims. Obviously, much like today, the first thing you had to do once you finally got to your shrine's town is get through the entry point—or, if in a distant, foreign land, go through customs, In medieval terms, this meant facing security, financial, and entrance issues before being allowed to approach a shrine or sacred site.

Entrance fees to get into the most popular Holy Land shrines in Jerusalem, in particular, were often high, if not downright exorbitant. The experience for any one pilgrim depended to a great extent on the vagaries of history—that is, precisely who was in charge of the sites at any given time over the centuries. During the two centuries spanning the period of the Crusades, for example, it might be the Christians in charge of the holy sites in Jerusalem for some years; at other times, their avowed enemies, the Saracens, controlled the Christian shrines. So getting through what we would today call “customs” could be extremely unpleasant on occasion for aChristian pilgrim if the Arabs were in charge—although sometimes they could be pleasant enough. But other accounts describe horrific experiences for some pilgrims, ordeals including experiencing high fees, taking one's personal items, and, at times, even stripping people of their clothing. There were reports of beatings, refusals to stamp documents, not allowing entry into Christian shrines even after the entrance fee had been paid, and demands that Europeans leave the country immediately. There could be antagonism the other way, too—as, for both sides during the long, bloody years of the Crusades, life was often very difficult for all pilgrims of any faith in the Holy Land.

Here are a couple of characteristic accounts from the early fourteenth and fifteenth century. Travelers described the infamous “nightmare” experienced while trying to enter Alexandria, where it was said, all travelers would be subject to very high fees and other forms of harassment. One Symon Semeonis reports that the officers examined the literature (guides and brevaries) he carried, spat on the holy images, broke some statuettes, but confiscated nothing. Another pilgrim, Joos van Ghistele, describes a virtual inquisition he encountered there in 1483, nearly a century later. Tax assessment of a traveler was determined by officers at the port of entry: “He attempted to pass himself off as a merchant, but the guard, who was not deceived, consented to tax him as a merchant but informed him that should his deception be discovered, the fine would be doubled! While they paid a lower tax per head, the merchants were charged more for their goods but suffered less harassment.” (2)

Next, after medieval pilgrims survived the ordeal of an entry point, they would check into a hostel or inn—if they were lucky enough to find appropriate accommodation at all. Then, they would join with many others, the throngs of fervent pilgrims, all desperately hoping there would be enough space for their entry to a major shrine on the eve of the saint's major feast day. The performing of a “nighttime vigil” at a saint's shrine was believed to be one of the most powerful spiritual practices of all.

The practice of the nighttime vigil at a shrine

According to the late medieval mindset, the goal was to arrive at the shrine early enough to join the “fortunate ones,” those who were allowed space in the cathedral. There, you would do a nighttime vigil at the saint's tomb—and, hopefully, get as physically close to the shrine as possible. But, in reality, few did. Once the huge, heavy cathedral doors were firmly bolted shut for the night, that was it—until after 6 AM the following morning. If you were without accommodation for the night, or were not strong or well enough to have fought your way through the crowds to get inside in time, it was a difficult and unfortunate situation, to say the least. Some did not survive.

If you were fortunate enough to get in, however, it still was not easy. Even after coming hundreds or thousands of miles, chances were not that great that you would get close enough to the shrine. But everyone tried his best, often battling the crowds. If you did get close enough, you would make an offering, pray, and once the authorities put out most of the candles for the night, attempt to sleep on your mat or directly on the cold stone floor—fervently hoping for an insightful dream, a blessing, or a cure for a loved one or yourself.

Many cathedrals would try to get the greatest number of pilgrims inside for the nighttime vigil. There was much crushing, and, at times, deaths would result. Among the casualties were inevitably women, with some reports of pregnant women being crushed to death, or children, the handicapped, or the elderly—in short, the vulnerable. Some pilgrims were crushed simply trying to assist other pilgrims. Such horrific circumstances were obviously untenable for all.

Although there were always watchful shrine-keepers and some attendant priests on hand, there were so many pilgrims at some shrines—especially on the eve of a feast day—that the officials available simply could not watch everyone. At the very least, overall security and “crowd control” were not developed skills in the Middle Ages:

Druids in Gaul, later the home of Chartres Cathedral.

At dawn on the feast-day itself, the congregation was turned out of the church, And the pilgrims returned to the lodgings. Auxiliaries cleaned up the mess and prepared for the services of the day. At these services the crowds were larger still, for the pilgrims of the night before were joined by most of the local inhabitants. The simplest techniques of crowd control seem to have been beyond the clergy of the sanctuaries, and accidents were frequent. This was the reason given by abbot Suger for rebuilding the abbey church of St-Denis in the 1130s. (3)

Although the nighttime vigil was a popular time for pilgrims to wish to visit a saint's shrine, other vigils were also made, and some of these historical accounts are quite revealing. Puy Cathedral is home to one of the greatest Black Madonnas. Once in an area sacred to the Druids and early Christians, it remains a popular shrine for pilgrims. The old town is built in terraces up the southern slope of an ancient volcano, Mont-Anis, and, as one French researcher has pointed out, it was a powerful mythic focal point for pilgrims, involving sleeping for one night on a stone:

The placement of Puy Cathedral (a magnificent Romanesque construction) as determined by the presence not of a spring or well nearby but rather of a volcanic rock known as a phonolite ... This phonolite slab, no doubt a dolmen table, had been previously used in a pagan sanctuary. This is probably the same stone that serves as the high altar, recut and blessed. Until the seventeenth century, a “fever stone” lay in front of the altar to Mary. Pilgrims seeking a cure for their illnesses would try to sleep one night on the stone, particularly Friday night. It is not clear why the clergy would have removed this stone, especially given that the same custom seems to have existed in Chartres before the destruction of the Romanesque cathedral ...” (4)

If we glance back through time, we see that spending the night at or near a shrine to inspire sacred dreaming (a practice known as “incubation”) was long an integral part of the ancient world. As Dr. Peter Kingsley points out when discussing the fundamental aspects of ancient Greek religion in In the Dark Places of Wisdom:

The existence of a hero-shrine was supposed to be a blessing for the whole area: for the land and the local people, for nature and for visitors. There was nothing casual about creating a hero-shrine—or about making it a part of your life. It was an opening to another world ... but there's one method of communication that they preferred to any other. This was through people's dreams. If you look back you can see the extraordinary consistency—and simplicity—in the way early Christianity converted the places that once had been hero-shrines into shrines for saints. There was hardly anything anyone had to do except change the names. And the one most fundamental feature that the Christian worship of saints took over from the Greek worship of heroes was the practice of incubation ... [as] the link between hero-shrines and incubation was so close ... (5)

The early Merovingians in Gaul, too, practiced techniques of dreaming and incubation in the early medieval period. (6)

An example of the belief in the inherent governing spirit of the landscape over time, the genus loci, is the legend of Melusine of Lusignan. (7) This important and enduring French myth concerns a powerful and elusive woman who would shapeshift into a mermaid and then back to human form. She and her family were intimately connected with this specific territory. As the reach of the Church extended further into more remote areas, connections to a specific region would often be explained in precisely the same manner as the stories found in hagiographical texts.

SAINTS AND MEDIEVAL SOCIETY

Before we explore shrines at a medieval cathedral, it is important to attempt to understand how people perceived their world in late medieval times, and how it was structured. Obviously, the saints played an important role in medieval pilgrimage—which is why pilgrims wanted to get as close as possible to the shrine; they understood their proximity as being as “one step closer” to God. The saints were seen by pilgrims as having miraculous powers and the ability to intervene and protect their own, sometimes quite dramatically.

Shrines on a pilgrimage

The shrines of saints were generally to be found inside a cathedral, monastery, or church. Shrines consisted of the remains of a saint or martyr, now possessed and claimed by that particular institution and its clergy, and held in their own special niche in secluded and protected areas. It was believed that if you personally went to and prayed at specific shrines, you might be forgiven for your sins and have a greater chance of going to Heaven. If you were very fortunate, you could receive insights, dreams, a healing, or blessings from the saint, either then, or, perhaps, later, after your return home. Over time, certain shrines became renowned for specific types of extraordinary cures—some became famous for bestowing the blessing of fertility to women while others were known for healing eye diseases, helping one with a family matter, or for freeing prisoners.

Going during the “off season,” before or after the saint's feast days and holidays, would allow one to avoid the very busy and crowded scenes, especially at the more popular shrines which had far greater crowds. Then, one could get physically closer to the relics themselves. All pilgrims, from whatever walk of life, hoped they might be blessed from their visit in some way. (8)

Pilgrimage sites were lively and crowded. Some people came voluntarily for the great love of a particular saint. Others were there because they had been sent by the authorities. In either case, the pilgrim would encounter huge, noisy crowds in the courtyard area outside the site, all clamouring to get in. At times, some of the most solemn and pious, it was wryly noted, were the very ones that could change disposition quickly! Competition was fierce; nearly everyone was exhausted from a long journey; tempers were short; and occasionally, scuffles and outbreaks of deadly violence would break out—especially in very hot weather.

Not only pilgrims would be milling about in the outer courtyard. A great variety of others would intermingle alongside the pilgrims, often creating a lively and raucous scene. Jesters, jugglers, merchants, rickety food stalls, pickpockets, incense dealers, gifted craftsmen and women selling their wares and art, produce and food hawkers, falconers, and so on might all be present. Historian Jonathan Sumption also points out that the overall situation changed little through the centuries, and was often quite irritating to the Church:

Pilgrims hobbling on crutches or carried on stretchers tried to force their way through the crush at the steps of the church. Cries of panic were drowned by burst of hysterical laughter from nearby taverns, while beggars played on horns, zithers, and tambourines. The noise and vulgarity which accompanied a major pilgrimage changed little from the fourth century, when Augustine of Hippo spoke of “licentious revels,” to the fifteenth, when the French preacher Olivier Maillard demanded an end to these sinful carnivals. (9)

Reading this today, we might envision a bustling summer street fair or colorful carnival in a larger town or city, the atmosphere being delightfully festive, creative, and lively. And, we might also think that after havingendured such a long, exhausting, and dangerous journey, one can well understand the pilgrims wanting to join in the fray before getting down to serious spiritual duties a bit later? Today, we know that many tired visitors, once finally reaching their destination and checking into the hotel, often first head for a restaurant, hotel bar, or a good pub. And who can blame them?

While, in some regions, the atmosphere would have been more solemn, in others, pilgrimage accounts tell us they were far more festive. Much depended on the time of year. The major feast days were by far the busiest times and drew the largest crowds. But nearly all pilgrims shared in the great excitement of being at a saint's shrine and sharing in what they hoped would be a transformative and sacred experience for themselves and their loved ones.

The most popular shrine in England was the tomb of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. When Becket was murdered, local people fervently managed to obtain pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumors soon spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness/epilepsy and leprosy. Historical accounts inform us that soon after, the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling more than a few small glass bottles of Becket's blood to visiting pilgrims. Visitors from far and wide came to Becket's shrine, including royalty and those from the Continent. Of course, Canterbury is still a highly revered shrine for religious pilgrims today, especially since the renovation of Becket's shrine in more recent years.

Thomas Becket disputing with King Henry II. In 1162, Henry had persuaded Becket, his Chancellor, to become Archbishop of Canterbury. They later had many disagreements. In 1170, Becket was murdered by three of the King's knights (Peter of Langtoft, Chronicle of England, 1307-1327, WMC)

Miraculous cures and healing dreams were reported at pilgrimage shrines, a number of which were later found to be totally genuine and reported by sincere pilgrims. Other accounts, however, were found to have been either heavily exaggerated or were outright falsehoods.

Another important English medieval shrine was at Walsingham in Norfolk, dedicated to Our Lady—one that later became designated the National Shrine of England. Here, there was a sealed glass jar that was said to contain the milk of the Virgin Mary. (10) On a visit to the National Shrine of England, the humanist scholar Erasmus made a journey to see the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham in 1513, some three hundred years after the “peak” of the 13th century medieval pilgrimage time. He commented that when you look inside, you would say it is the abode of saints, noting that it seemed to shine on all sides with gems, gold, and silver—an image remarkable neither for its size, material, or workmanship, but nonetheless powerful in its sheer effect upon the visitor. Previously, in medieval times, pilgrims to Walsingham would first bathe in its curative waters, and then go through a narrow wicker gate called the Knight's Gate before they finally viewed the celebrated statue of the Virgin Mary. In the priory church was a phial of the Virgin's milk. Among the designs for medieval Walsingham pilgrim badges are especially those that show images relating of the Annunciation of Mary, the Virgin in the Holy House. There are also badges showing Sir Ralph Boutetout, who it is said, in 1314, barely escaped enemies in hot pursuit because of his fervent invocation to Our Lady of Walsingham. (11)

Today, Walsingham has two shrines, one Catholic and the other Anglican. The guidebook states that during the summer months, a particular visitor attraction is the Candlelight Procession of Our Lady on Saturday evenings at the Anglican shrine. A special highlight at the Catholic shrine is the daily evening (Easter to October) Pilgrim Service at the church of the Annunciation and in Elmham Gardens. Interestingly, there has been anew ecumenical development in recent years—an Orthodox presence at Walsingham. The Orthodox Church has the use of a small chapel on a landing at the Holy House; while the former Victorian railway station building nearby has become the Orthodox Church of St. Seraphim, complete with a small onion dome on the roof.

Many other shrines that were key stops on a medieval pilgrim's list are still visited today. Visitors range from devout religious pilgrims to secular tourists incorporating a visit to a cathedral on their itinerary when in a specific area. Shrines open to the public today may be found at Aachen, Eindelseln, Cologne, Montserrat, Vezelay, Rocamadour, Orleans, Chartres, and Compostella, Canterbury, Walsingham, among many other places.

But why were the shrines of saints, in particular, so important in the Middle Ages? Pilgrims would honor those who had performed God's work in their lifetimes and now had been elevated to join with God in influencing the physical world—that was the rather typical medieval way of viewing it. A devout belief in the enduring power and influence of the saints—even after death—was heavily engrained in the medieval Christian psyche and seems never to have wavered in a pilgrim's mind. These special sites were believed to possess the highly charged spiritual energy of the saint, who was viewed by visitors as being very much “alive.” People felt the sanctity of sainthood would “rub off” on them during a visit to a shrine, and so they wanted to get as close to it as possible:

similar to radioactivity that affected anything they touched. The belief was that the farther away one stood from the object, the weaker was the effect. Thus, a person who hoped for a miracle cure needed to have direct or near-direct physical contact with the relic. Because of this tendency to radiate, if a sacred object is left unconfined or exposed, its powers will dissipate ... For this reason, care must be taken to construct a container to house it ... (12)

Wood, silver or gold-encrusted reliquaries that contained the relics were thus extremely important at a shrine, its focal point for many pilgrims. Most reliquaries were small to medium-sized casket-shaped containers. They were believed to “hold in” the power of the saint's relics, to concentrate its energies and keep it from dissipating. Those reliquaries that have managed to survive the ravages of time are amongst the Western world's greatest objects of medieval art. Some are beautifully simple, while others are exquisitely designed and ornately carved, adorned with jewels and precious stones. These special boxes or caskets were also carried into battle on important occasions, or carried through a town as part of a special Church pageant or procession.

Major cathedrals and the larger churches often had at least one official at a shrine who was its guardian, He was called a feretrar, a term from the Latin word “feretrarius,” meaning shrine-keeper. Canterbury, Westminster Abbey, Ely, and Durham all had feretrars, some of whom also had assistants due to the great number of pilgrims. These ever-watchful security guards worked feverishly during feast days especially, to attempt to keep pilgrims from being crushed in the melee of those trying to get close to the saint's relics.

RELICS IN THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES: AN INTRODUCTION

To a pilgrim, the real power of God's holy miracles was believed to be present in a relic. It is important to realize today that, to the medieval mindset in particular, the relic itself was not venerated per se, but the power of God was believed to work in or through a saint's relic in a most extraordinary way. A relic might be said to be a part of the body of Christ, or of a specific saint or martyr; it could also be an object that had been closely connected with a saint's life. For example, a relic could be a piece of a saint's clothing, or special possessions during life like a Crucifix, or prayer beads, an illuminated Book of Hours, or a Bible. Of course, the most precious relics were those said to be associated with the Holy Family. Especially prized were relics relating in some way to the Crucifixion, such as various fragments of the True Cross, the Crown of Thorns, nails, even drops of the Holy Blood held in glass vials. Kings, too, would often feature relics in their building projects. One key example is when Louis IX of France built the stunning Sainte-Chapelle in Paris in the 1240s, renowned for its stained glass. The building was intended as a reliquary for some of the holiest relics—part of the True Cross, part of the Crown of Thorns, and other precious relics he had obtained from King Baldwin in Jerusalem. Historians note that a number of relics and other religious objects from the vibrant trade with the East were brought back by returning Crusaders, pilgrims, kings, merchants, and others. (13)

Relics of saints were sometimes placed in the foundation stones, altars and the tops of spires of churches. The idea was that the power of God, via the relic, would permeate, radiate out, and protect the entire building and environment around it, as well as the parishioners who worshipped there.

Chartres, in particular, presented the pilgrim with a positively dazzling display of medieval splendor in architecture, sculpture, stained glass—and, of course, relics. Chartres' most famous relic was the cherished “tunic of the Virgin Mary,” the very cloth said to have been worn by The Blessed Virgin herself when giving birth, and:

by the later Middle Ages, the Virgin's tunic (a 16-foot long piece of silk) was but one of the many treasures possessed by the cathedral.... there were [also] several hundred miraculous statues, a miraculous well containing the relics of local martyrs, even the head of St. Anne, the Virgin's mother, purchased by Louis the Count of Chartres from the sacred booty looted from Constantinople in 1204 by the crusaders. (14)

Exquisite stained glass windows of Saint Chapelle in Paris. (Karen Ralls)

Healing and medical issues at shrines

Visiting pilgrims would nearly always come bearing gifts to be left at the shrine in great hope of getting needed help from the saint. Many donations were not money per se, but valuable objects that the pilgrim could afford. An offering of some type was an indispensable part of any pilgrimage whether or not a miracle was sought; cathedral records occasionally tell us of an intriguing variety of coins left at a shrine. Some were very rare, others rather routine, and some were illegal! At Durham, for example, accounts show that Scottish, French, the Anglo-Gallic gyan, crowns, and other currencies were deposited at the shrine. Non-sterling coins were recorded “as a separate sum, presumably because they were jointly disposed of by being sold to a money-changer or a silver-smith.” (15)

When an illness was cured by a visit to a shrine, a wax effigy of the affected part of the body, or sometimes a donation of wax equal in weight to that of the sick person would be left. Or, if the whole body were diseased, a wick the length of the person could be coiled up and waxed to make a “trindle candle.” (16)

Medieval pilgrims could also ask designated saints for help about a particular area of concern in which a certain saint was believed to be a “specialist,” including health issues. For example: St. Giles for leprosy; St. Nicolas for rheumatism or infertility; Our Lady, the Blessed Virgin Mary for nearly all troubles (and especially for fertility-related concerns for women); St. Christopher for the safely and well being of travelers; St. Leonard for prisoners; Sts. Dunstan and Eloi for blacksmiths; St. Cecilia for musicians; and let's not forget the saints for vintners and the wine trade, St. Amand and St. Vincent of Saragossa!

More serious concerns were focussed on healing, the state of one's soul, and praying for the forgiveness of sins.

Shrine of the Black Madonna at Montserrat. (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

BLACK MADONNA SHRINES AND HEALING

While many shrines of Our Lady were reported to have bestowed a special dream, blessing, or powerful healing experience or miracle, some of the most consistently reported miracles over the centuries featured a Black Madonna shrine, such as those at Montserrat, le Puy, Rocamadour, Orleans, and so on. Some of the favorite medieval Black Madonna shrines, even today, include the shrines at Chartres, Einseldeln, Oropa, St. Victor's (Provence), and Vezelay. I covered a number of these in my previous book Medieval Mysteries. There are over 450 Black Madonnas throughout Europe—of varying ages and condition—but many are still well-preserved and are some of the most beautiful and well-maintained shrines today. Here are a few more that are often of interest to those seeking healing and spiritual blessings. (17)

Tenerife, Our Lady of Candelaria, Black Madonna shrine. (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

Black Madonna of Candelaria (Tenerife)

An intriguing, but lesser known Black Madonna site is in Tenerife at the shrine of Candelaria. Modern-day visitors have reported powerful dreams and healing experiences here. One of the principal Canary Islands in the Atlantic, Tenerife has a fascinating history and intriguing archaeology. A picturesque village on the west coast, Candelaria continues to enchant. Its sea wall is decorated by nine huge statues of the Guanches—the ancient Berber kings who ruled the island long before the arrival of the Spanish in the fifteenth century. The legend says:

at the end of the fourteenth century, the Guanches found a wooden statue which had been washed up by the sea just south of Candelaria. Thinking it might bring bad luck they tried to destroy it by throwing stones, but tradition says that they found themselves temporarily paralyzed. After this experience, they credited the image with miraculous powers, though they had no idea whom it represented. It was a Black Madonna. (18)

Black Madonna of Laon Cathedral (France)

The famous statue of the Black Madonna in the city of Laon in Picardy is certainly worth a visit. Inhabited since pre-Roman times, “There was an important colony of Scots and Irish in Laon in the ninth century, which included John Scotus Erigena, the leading neo-Platonist theologian of his age ... The Cathedral, built with the aid of a magic ox, has remarkable statues and carvings of oxen.” (19) Laon was once a key locale for the Merovingians, and later served as the Carolingian capital of France. Today, it contains a number of beautiful twelfth and thirteenth century buildings—including its stunning cathedral, Notre Dame de Laon, perched high up on the craggy hilltop that graces the skyscape of the city.

Its chapter house has especially fine examples of the architecture of the early thirteenth century. The front, flanked by turrets, is showcased by its large stained glass windows with their fascinating geometric stone tracery designs. There is also a beautiful Gothic cloister and an old chapel of two stories, of an earlier date than the cathedral itself. Laon was also one of the key cities dedicated to Lugh, an ancient Celtic deity, as was Lyons.

Jungian analyst Ean Begg in his study comments that “Lugh's other major city in France, Laon, the Carolingian capital, boasts a Black Virgin, a Templar Commandery, and a bull-festooned cathedral.” (20) Also regarding Laon, the Black Madonna expert and French historian Durand-Lefebvre referred to a Black Virgin statue that was donated in 1818, a modern statue in which the Virgin is crushing the serpent. Another French Black Madonna historian, Saillens, describes in his classic account a new devotion to a Black Virgin in wood (150 cm) in 1848, which was found to have been based on Notre Dame de Liesse. In the center of the great stained glass rose window at Laon, many note that the hands of the Virgin and Child and the face of the latter appear to be darkened, or black.

Black Madonna shrine at Laon. (Jen Kershaw)

Western tower of Laon Cathedral, Picardy France, showing its carved oxen. (Cayau, WMC)

Laon “has a well-preserved Templar chapel containing a disembodied stone head evocative of Baphomet, and a museum next to it with a triple goddess of the Gallo-Roman period with very large hands.” (21) The current Black Madonna shrine at Laon is striking. Accounts of various types of healings, dreams, and meditative blessings have been said to occur at Black Madonna shrines since medieval times. Laon has had its share of such accounts from visiting pilgrims, both modern and medieval.

“Miraculous healings” at pilgrimage shrines

Accounts of extraordinary healings in the often historically-neglected Black Madonna shrines, continue to the present time. As a number of these shrines are placed in the crypt, the darkest part of a cathedral, the Latin phrase Lux Lucet In Tenebris (“Light shines in darkness”) may be particularly apt. In earlier times, the color black symbolized Wisdom, and darkness was not feared as it so often is today. Symbolically, a healing of the greatest light, a miracle to a medieval pilgrim, is seen to originate from the shrine in the darkest place on the premises—a union of both light and dark.

A common misconception today is that most of the miraculous healings in the Middle Ages took place right at the shrine itself. Actually, while a number were claimed to have done so, it is thought that at least half or more of the reported miracles in the High Middle Ages actually occurred afterwards, within a pilgrim's home or another location, and were later credited to the saint's shrine. (22) Cures were not always experienced on the first visit either—it could often take several visits before a full-fledged miracle might occur. Naturally, the registrars at medieval shrines were prepared to record any and all cures reported, but the pilgrim would later be required to produce a witness. Many legitimate, devout pilgrims gladly did so; however, there were still some who faked cures, or worse; some churches who were found to be directly complicit in the deception in order to gain more fame and money for themselves.

If a medieval pilgrim received no cure or relief at all, in spite of their long, arduous journey and faith, they must have been utterly devastated. Many had heard of miraculous cures at a particular shrine from others and would give up nearly everything they had to travel there under very difficult circumstances, only to find in some cases, it was to no avail. In certain instances, people would stay at shrines for weeks, even months at a time, convinced that the relief of a miracle cure from on high was imminent. There are reports of others who, having been totally cured, decided to stay on, afraid that the illness might return if they dared to leave the area. One pilgrim, said to have been cured of his epilepsy, was utterly terrified to leave, and so resided at Becket's tomb for a further two years!

Pilgrim's Badges

Mementos and trinkets, like small flasks, were available to pilgrims, often sold in booths in the outer courtyard area leading up to the cathedral itself. Pilgrim's badges, each unique for a particular shrine, were collected so pilgrims could legitimately “prove” they had been to Rome, Compostella, Jerusalem, Walsingham, and so on. They would affix them to their hats or cloaks. The badges became a status symbol. Today, the Museum of London has one of the best collections of medieval pilgrim's badges—worth a visit for those interested.

Seal of parishioners of St. Mary Magdalene Church, Oxford 1326

Scallop shell, the emblem of St. James, Santiago de Compostela (Simon Brighton)

The most well-recognized pilgrim badge was the palm of Jericho symbol from Jerusalem; from Compostela, it was the scallop shell; tokens from Canterbury took many forms like a picture of St. Thomas wearing his bishop's mitre, a picture of the head of Thomas, or his gloves. About seventy examples of St. Thomas Canterbury badges have been found at the French shrines of Mont-Saint-Michel, Rocamadour, and Amiens. (23) There were a great variety of other such badges, as shrines were numerous.

Pilgrims' badges were also highly prized as a kind of “magical charm.” They were believed to have a special power. A badge of Rocamadour was said to have cured a pilgrim's ailing son. Miraculous powers were often attributed to coquilles-Saint-Jacques, one of which was alleged in c. 1120 to have healed an Apulian knight suffering from diphtheria. Badges were also used to prove that the wearer was entitled, as a pilgrim, to exemption from tolls and taxes.” (24)

In addition to much else, the medieval Knights Templars in Europe assisted pilgrims by sea, transporting them to and from the Holy Land, along with other goods and supplies. The Templar ships were the most secure any pilgrim could hope to travel on, so a place on one of their galleys was highly coveted. The Templars would certainly have recognized legitmate pilgrim's badges, but the Order itself did not manufacture pilgrim's badges.

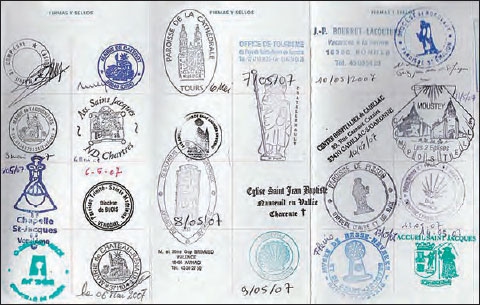

Example of a modern-day “pilgrim's passport,” showing the stamps from shrines along the Camino to Compostela. (WMC)

Cathedral shrines had to fight hard to preserve the uniqueness of their special emblem or symbol, somewhat like our concept of trademark today. For instance, Pope Innocent III ruled in 1199 that the Basilica of St. Peter in Rome should have the monopoly over the production of pilgrim badges showing St. Peter and St. Paul. Anyone or anywhere else that was caught doing this faced severe penalties.

SEEDS OF CORRUPTION GROW

Counterfeiting Pilgrim's badges

Inevitably, some people started abusing the pilgrim badge system. One result was a brisk trade developing in various places of fake badges. While this issue became of great concern to the Church, they found it impossible to stamp out. A great many black market operators were involved who were unknown to Church authorities. There were frequent complaints of beggars picking up a cockle-shells from a beach and pretending to have been to Compostela, or of newly-released criminals specializing in masquerading as pilgrims on the highways of Christendom. This problem continually grew, prompting Richard II, in 1388, to decree that people claiming to be pilgrims had to produce a proper letter of passages stamped with a special seal. If they didn't, and were able-bodied, they were to be immediately arrested. This was like a medieval version of identity verification today.

Chaucer, The Pardoner, from an edition of The Canterbury Tales published in 1492. (WMC)

The growing problem of illegal trade in artifacts and relics

Many valuable artifacts and goods—and a fair number of relics—were brought back by returning pilgrims, especially from the Holy Land and the East. In the eyes of the Church, such artifacts and objects came legitimately, i.e., with a definite religious intent or purpose in mind. However, such objects were bought illegally in great quantities with the sole intention of selling them and making money back home, with no religious or spiritual intent. So, while “customs” issues were something with which every pilgrim had to contend when entering a country or approaching a shrine, some of the more lively customs problems occurred upon return from a pilgrimage. Quite often, middle level and wealthier pilgrims, aware of the very high prices that certain goods from the Holy Land could fetch back home, tried to smuggle in what they could. Most of these types were obviously not devout religious pilgrims, but some actually were.

Others were members of the Church itself. Here is a rather shameless example of St. Willibald of England in the summer of 721. It features the balsam resin:

On his way back from Jerusalem, Willibald smuggled some balsam past the Arab customs officials at Tyre in a jar with a false bottom, remarking to his companion that had he been discovered he would have “suffered there and then a martyr's death.” Plainly, Willibald saw nothing wrong in his behavior. (25)

Many pilgrims simply could not resist the temptation to buy incenses, exotic spices, money, and precious cloths in Jerusalem and other exotic lands and sell them for much more back home. While there have been endless conflicts about religious issues, trade, and politics over time, pilgrimage seems to have deftly brought all these controversial threads together into a heady mix. Powerful and deadly merchant cabals were formed on the highseas, highways and byways to and from the East; various monopolies and embargoes were strongly enforced. At one point, China imposed the death penalty on anyone who tried to break the country's monopoly of the silk trade, so great was its value. Some wily monks “reputedly succeeded in smuggling silk-moth eggs hidden in their staves into Byzantium, where a thriving silk industry soon arose.” (26)

Religious relics were brought back by returning Crusaders or devout pilgrims, but some precious relics were obtained by merchants and other travelers via less than honorable means. “There are accounts of bishops taking reliquary bones away with them after they had been succeeded, and both Vezelay and St. Foy in France, and St. Mark's in Venice were in possession of relics that had undergone ‘sacred theft’ from another church.” (27)

The even more disturbing trade in fraudulent relics

A much larger problem than fake pilgrim's badges, or smuggled or even stolen relics, were fake sacred relics. An early, major contributing factor to the eventually untenable problem of fraudulent relics was an edict by Pope Gregory the Great in the sixth century. He said a relic must be housed in a church before the building could be consecrated. As being an unconsecrated church was simply unthinkable in the Middle Ages, churches were under tremendous pressure to find relics as soon as possible, by fair means or foul; any relic might do.

The absolute requirement by the Church for possessing relics helped facilitate a lively trade in fraudulent relics. Medium and smaller-sized churches simply could not risk being without a relic—or three—let alone a major Gothic cathedral. One absolutely had to have a relic—or else. That was the policy. So the administrators of churches and monasteries would often do nearly anything to get a relic for their premises, as they felt they had no choice. Relics would attract more pilgrims as tourists, attract more contributions, and gain needed favor with Rome. Inevitably, churches, abbeys, and monasteries became very competitive with each other for relics—and pilgrims.

Since there weren't enough genuine relics to go around, this situation led to a thriving trade in bogus relics beginning in the seventh century, well before the Gothic age. Former regulations protecting the exhumation or dismemberment of bodies of the dead were disregarded. In the eighth century, Pope Paul I took to opening up the graves of Rome and donating the contents to those churches unable to abide by his predecessor's edict.

The logical development of all this was that counterfeiters began a burgeoning production effort. They moved from fake pilgrim's badges to the more lucrative trade of robbing graves and selling the bones to the unsuspecting. Chaucer's infamous Pardoner in The Canterbury Tales sold pig's bones!

And in a glas he hadde pigges bones.

But with thise relikes, whan that he fond

A povre person dwellinge upon lond,

Upon a day he gat him morre moneye

Than that the parson gat in monthes tweye. (28)

Upon hearing a steady stream of accounts of an increase in fraud, unscrupulous trading, and outright exploitation of pilgrims, the Church authorities in Rome understandably became concerned. They feared that these illegal activities would damage the Church's reputation. Yet, it was nearly impossible to stop these rackets, run by increasingly sophisticated criminals.

There were other problems associated with relics as time went on. The Church validated the transportation of holy relics from one site to another, which would generally occur at night for security reasons. This practice accounted for the problem of multiple-ownership claims to a single relic. One rather ridiculous situation featured five or six churches claiming an arm of St. John the Baptist, or the same piece of the True Cross. To complicate matters, the lucrative trade in illegal relics led to the circulation of unmarked saint's bones over different sites. There arose fierce squabbles as to the authenticity of relics among churches, abbeys, and monasteries. Records show that the monks of Poiters and Tours fought over the body of St. Martin, while Canterbury and Glastonbury found themselves at loggerheads over St. Dunstan's remains. Over time, such battles became rather commonplace as institutions competed for prestige of the best collection of relics.

The problem of illegitimate relics was recognized by the church as early as the sixth century. Ecclesiastics used the “fire test” to determine if a particular relic was real. After being thrown into a fire, the theory was that a true sacred relic should be able to withstand the flames. If not, it was said to be fraudulent.

More exacting methods were carried out in later centuries. In the twelfth century, an edict stated that no church may possess relics unless they had first met with Episcopal approval. Pope Innocent III followed suit in a 1215 ruling requiring that all relics needed the approval of the Roman pontiff. In spite of such measures to genuinely try and stem the massive problem of illicit trade in relics, some churches coveted the gains to be had by exhibiting fake relics, and would cynically turn a blind eye: some because they wanted to; others because they badly needed the money that relics and pilgrims brought in.

The growing problem of selling indulgences

But the problem of fake relics and the gross exploitation of pilgrims weren't all. As the years went by, the growing trend of selling and purchasing pardons and indulgences became pernicious. (Indulgences were formal acts governed by the Church that certified forgiveness for past sins.) The blatant corruption of this practice would eventually spark the first stages of the Protestant Reformation.

The opportunity to receive indulgences was a powerful incentive to go on a pilgrimage. Those who received indulgences were to be spared enduring more time in Purgatory after their deaths. Purgatory could be described in modern terms as a long, liminal, after-death state of uncertain duration whose purpose is to cleanse and purify the souls of those on their way to Heaven—like sitting in a doctor's waiting room for what seems like endless hours.

The Church's official policy was that shrines assumed a value relative to the amount of remission time they offered. For instance, in arriving at St. Peter's on a major feast day, it was said that a pilgrim could obtain up to seven years “credit” off one's time in Purgatory. So naturally, the more one traveled to major shrines, the better. Many shrines were legitimate and the system of granting indulgences was not abused. However, as time wore on, the situation became tragic—as many noted both within and without the Church.

With all the competition we have seen regarding relics and the desire of various churches to attract pilgrims, eventually, it is no wonder that indulgences were cynically recognized as another valuable commodity. Religious institutions ran sales specials or “bargains of the month.” They would offer indulgences and pardons for pilgrims with more benefits than usual—essentially a fevered sale pitch of “come to us, not them!” So pilgrims who wanted to get the best for their money would try to attend the church that made the best offer. Here is an example:

the monastery at Shene in Surrey, England, offered the following sales special “deals” on indulgences and pardons in the fifteenth century: on the Feast of St. John the Baptist whoever comes to the monastery and devoutly says a Paternoster shall have ninety days of pardon ... on the Feast of Mary Magdalene whoever comes to the said monastery shall have one hundred days of pardon granted by Biship Stafford, Archbishop of Canterbury ... on the feast of St. Thomas the Apostle and in the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel they shall have three years and forty days of pardon ... (29)

Accounts show that if one could not take a pilgrimage—as required by Canon law—you could simply pay the Church the amount of money you would have had to spend if you had gone. This was an option often exercised by wealthier pilgrims who claimed they were too busy with their estates or business affairs. As the years went by, the overall scenario became increasingly appalling in certain locales; in describing this situation, one modern British author wrote, “the Holy Grail of the tourist trade had been found: “Don't bother to visit, just send your money!” (30)

Only a limited number of shrines were actually allowed to dispense indulgences—the “premier” major shrines, you might say. If your church, abbey, or monastery was not on this coveted list, it became increasingly hard to compete for and attract pilgrims. Just as religious centers sought to promote the superiority of their relics collections and the miracles they performed, those churches which the papacy authorized to dispense indulgences had an extra “bargaining chip” with which to attract pilgrims—especially the wealthier ones and the vast sums of money and gifts they brought with them. This meant that the churches that were excluded would often find themselves in a desperate situation—some even resorted to forging indulgences. While the Pope had overall jurisdiction in this matter, bishops often gave themselves the power to grant indulgences. Obviously, some got totally out of hand.

In the seventh century, the idea that penitential acts could work to reduce the amount of time spent in purgatory was advanced. Before indulgences were more widely available, penance could be paid during one's lifetime through a chosen punishment equal to the weight of the sin. The gravity of the sin committed could also be lightened by performing good deeds. Going on a pilgrimage was seen as one such act. It was only later that collecting indulgences at shrines became the penitent's tangible assurance that his stay in Purgatory could be reduced.

There were two types of indulgences—partial, which released the sinner from a fixed period of time in purgatory, and plenary which granted full remittance from all penitential suffering. Complete remission was offered to those who went on Crusade, for example. For those pilgrims who went to Rome—and who died or met with some genuine misfortune either en route or while performing their duties there—allowances were made. They might still be granted their indulgence. But not always.

Jubilees

In the year 1300, Rome's first jubilee year, Pope Boniface VIII offered plenary indulgence to all those visiting the basilicas of St. Peter and St. Paul. For pilgrims coming from abroad, a stay of fifteen days was required. It was a most controversial policy. When challenged from within the Church, it was stated that the indulgence declared the penitents as free of guilt and sin as the day they were baptized.

Boniface's successor, Pope Clement VI, yielded to the increasing pressure and spaced out the jubilee period to every fifty years. So the next jubilee was to be held in the year 1350. After that, pilgrims were also required to visit the Basilica of St. John, as well as those of Peter and Paul, and only then would they receive complete forgiveness of all their sins. Over time, the importance of going on a pilgrimage to benefit from indulgence dissipated. The sick or elderly, for instance, could either send money to a shrine of their choice or else pay someone else to go for them. Of course, the Church in Rome benefited greatly from the many offerings and payments of the whole indulgence system.

As with the trade in fraudulent relics, the sale of unauthorized indulgences gradually became a real farce, to put it mildly. Many within the Church—including Martin Luther, Thomas More, and John Wycliffe—strongly objected to such unscrupulous practices. Despite attempts at preventative measures by the Church to avoid misuse of the system, accounts show that, far too often, credulous pilgrims were preyed upon. The situation was so bad that in England the government stepped in. Royal injunctions were introduced in 1538, instructing every parish, “to remove any images which had ‘been abused with pilgrimages or offerings’; to regard the surviving representations of saints simply as memorials, and to be prepared for the removal of more later; and to reject the veneration of holy relics.” (31)

The notorious “pardoner”

The chief suspect behind much of this corruption was the pardoner, an ecclesiastic dealer in indulgences. The pardoner's primary role involved traveling around, retailing the “merits” of the relics of saints and martyrs in exchange for worldly goods and gifts to be donated to the seat of the Church in Rome. (32) However, to the consternation of Rome, many of these pardoners had, in fact, set themselves up in business entirely independently—with no ecclesiastical authority at all. The became “laws unto themselves.” They carried convincing-but-inauthentic licenses and wrongly claimed to have papal approval for their work. They thereby reaped lucrative and ill-gotten gains for themselves.

Chaucer's pardoner, while entertaining to read about, is an example of the cunning and deceptive tactics used by an unscrupulous pardoner—a combination of scaremongering and dramatic displays. He is described as having a voice “as loud as a bell” that captures the attention of his victims, preaching with heavy irony on the goodness of heaven and the dangers of Hell. He hawks his wares using wild gesticulations of his arms and has wide, staring eyes that flash about or keep an intense gaze, holding his audience captive. He carries a pillowcase which he exhibits as the Virgin's veil, and his relics, we know, were his legendary pig's bones which he claimed were the bones of a saint. In one day, Chaucer reckoned, such clever deception would earn the pardoner as much money as a parson would make in three months!

Eventually the office of pardoner was officially abolished by the Church at the Council of Trent in 1562 on the grounds that “no further hope can be entertained of amending” their deceptive ways. Yet, it was too late for many of the well-meaning, naïve, and faithful pilgrims who had fervently believed they could save their souls and avoid the fires of hell by purchasing his fraudulent, illegal wares. Perhaps that is one of the greatest tragedies of all within the great “age of pilgrimage.” It seemed as if God and Mammon had forged a most unholy alliance.

One might say that the official elimination of the “pardoner” position in the system was like a mere “band-aid solution” in today's political parlance. It could not ultimately stop the other illegal and unscrupulous dealings that were still going on in various quarters. These were officially outside the Church's direct control and had been set up by private individuals and their various networks. So after the Council of Trent's decree, many ex-pardoners simply changed from selling indulgences to touting other religious products like fake relics, and other scams. These kinds of corrupt activities were hard to pin down.

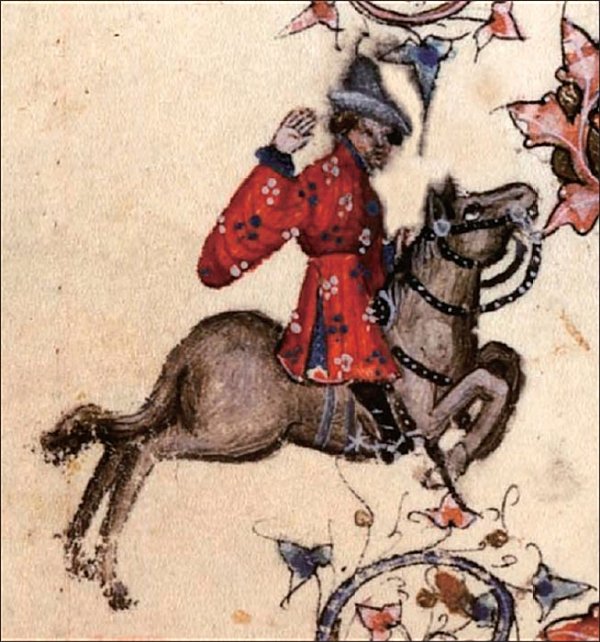

Medieval merchant depicted in the Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (WMC)

SECULAR TRAVEL: THE MEDIEVAL MERCHANTS

As we have seen earlier, not all medieval travelers were pilgrims on a religious journey or pilgrimage. Traders along the way also faced dangerous travel conditions. Legitimate medieval merchants would often need to make long perilous journeys to deliver and sell goods. They developed a series of special “safe houses” in the important foreign trading centers like Venice, where they could rest. (33) They, too, had to take special, elaborate security precautions to properly guard their goods and persons from thieves and murderers.

One rather humorous-but-true story about traveling medieval merchants concerns a German-speaking merchant group's choice to stay in a safe house in medieval Venice. Their very valuable goods and merchandise were guarded by bloodhounds while they stayed in town en route to the Holy Land. But, rather like specialized, trained guard dogs today—and long before our modern security alarms, movement-sensitive lights, iPhones, and the like—these dogs had been specially trained to growl and attack upon hearing any language other than German! If the sleeping merchants heard their dogs begin to growl and carry on during the night, they knew there were either unwelcome intruders attempting to break in the building, or already on the scene, and would spring into action to protect their goods. (34)

Such traveling merchants would often be going to the same cities, towns, and cathedrals as religious pilgrims, and penitents. There was always some interaction between the two groups. While the priority of pilgrims was to worship and go to a shrine, conduct religious services, fight in the Crusades, or hope for a miraculous healing for themselves a friend, or family member, merchants sought to sell rare, valuable, legitimate goods, barter at fairs, exchange goods for services, haggle with the tax man at customs upon entry, get a better deal on hostel rates for the next journey. As historians have noted, for the unscrupulous merchant, the primary hope was to sell fraudulent relics or indulgences to all and sundry.

Medieval travel often did involve a great variety of companions one met along the way. It was essentially a hodgepodge of many individuals, ranging from all walks of life; all were headed in the same direction, and at times, assisting each other in the process.

Decline of the heyday of pilgrimage

Difficult and dangerous as many pilgrimages were—especially for the sick or crippled in search of a cure—a decidedly festive atmosphere when danger had passed could lead to situations where “frivolous matters” were said to have got “out of hand,” not unlike problems today caused by traveling “hooligans.” After the peak of pilgrimage, especially, as time went on the growing number of incidents like this eventually led to increasing criticisms about pilgrimage in general. This was compounded by concerns about the selling of fraudulent indulgences and other corrupt practices. By the sixteenth century the crescendo of criticism inevitably came to a head. A major head.

In England: Henry VIII orders an investigation (1535)

In August 1535, after being unable to get a divorce from the Church, Henry VIII decided to send a team of officials to ferret out exactly what was going on in the monasteries. Every object, artifact, reliquary and so on was to be duly catalogued with no stone left unturned, resulting in a huge effort. After reading the various reports, Henry chose to close down some 376 monasteries in England. Church land was seized and sold cheaply to nobles and merchants. In 1538, Henry turned his attention to the religious shrines. Wealthy pilgrims often gave expensive jewels and ornaments to the monks that looked after these shrines. Henry decided that the shrines, too, should be closed down and their great wealth given to the Crown.

The Pope and the Church were aghast when they learned that Henry VIII had destroyed St. Thomas Becket's shrine at Canterbury. Henry had ordered that Becket's holy bones be scattered. He further decreed that any images of Becket within the kingdom be totally destroyed. No one was allowed to call him a saint any longer. This was the final straw in the ongoing conflict about Henry's controversial desire for a divorce. On 17 December1538, the Pope announced to the world that Henry VIII had been excommunicated from the Catholic church. (35)

Other events affecting the Church began to occur all over Europe. Martin Luther's earlier posting of his 95 Theses in 1517 at Wurtemburg, eloquently outlined many of the abuses of the Church, especially the selling of indulgences. More people began questioning what was going on; the debates were intense. The beginnings of the Reformation started in earnest. Key Protestant leaders such as John Calvin in Geneva and John Knox in Edinburgh, followed suit. For better or for worse, the European Christian world would never be the same again.

Pilgrimage suffered greatly as a result of all of these factors. By the late fifteenth century and into the sixteenth (the time of the Reformation), pilgrimage had declined to a mere trickle. This period also saw a wholesale rejection of relics, holy images, and indulgences. In England, all usage of the term, “Our Lady,” let alone any veneration to Her, were actively discouraged by the Crown. The Walsingham shrine—the national shrine of England—suffered terribly. Henry VIII's destruction of shrines and the dissolution of the monasteries (in total 563) broke the backbone of the pilgrimage tradition in England. It has been alleged that roughly nine thousand monks and nuns were pensioned off, and many valuable manuscripts, reliquaries and art objects were thrown out, melted down, buried, or destroyed. (36) It was clearly the end of an era. And for art historians today, it was also a devastating travesty. So many medieval artifacts and objects were destroyed in England at that time, that it has been difficult to piece together what occurred in certain locales to this day.

PILGRIMAGE AND TRAVEL TODAY

Although pilgrimage declined precipitously by the sixteenth century, it did not end. It still gave much spiritual sustenance to many. Today, going on a pilgrimage—as opposed to a “tour”—continues whenever people are transformed by their journey. Sacred travel today is open to those whose spirituality tends to be more open and less defined than in medieval times. Pilgrimage can reach us on a deeper universal, human level, regardless of belief, faith, race, or creed. The desire to share in the beauty and awe of nature and sacred sites is alive and well.

There is, in fact, a modern resurgence of interest in the art and beauty of Gothic cathedrals, and their grounds and gardens. There is a corresponding increase in travel to European Gothic sites and cities.

Before we know where we are going, we need to understand from whence we have come as a people and a culture. Today, we have been conditioned to believe that “history” as written relates only to the past, as a way of recording facts. Yet, as many travelers can attest, the past can often be most appreciated and experienced by visiting historical places and sacred sites—a “hands on” approach, beyond any guidebook.

To reconnect with the sacred by traveling to a special place is often called a “pilgrimage.” This is not the same as “traveling” or “being a tourist.” Why? Because traditionally, pilgrimage has always involved taking a risk. The profound risk that you may not only never come back—which was a reality in the High Middle Ages—but that if you do return, you may never be the same again.

Pilgrimage is no ordinary journey. Medieval pilgrims knew this, and made many sacrifices to get to their final destination. Some, if they could, returned to a site several times, or made annual return visits. Some people today, religious or not, make similar sacrifices to visit to a favorite place with special meaning for them. Others feel no particular need to do so. They may prefer to make their pilgrimage “within.” Many do both at different times in their lives.

Pilgrimage is a journey to the center. It is to travel to a sacred place for inspiration and wisdom, to re-connect with the wonder and awe of the Universe, however you choose to define it. Whether one travels a long distance to a geographic location, or explores the inner world of the heart, the unifying concept is the same. Pilgrimage is not an “ordinary journey.” We are here reminded of a famous quote by Sir Walter Raleigh, in his 17th century work, on Pilgrimage:

Give me my Scallop shell of quiet,

My staff of Faith to walk upon,

My scrip of Joy, Immortal diet,

My bottle of salvation,

My gown of Glory, hopes true gage,

And thus, I take my pilgrimage. (37)

Wherever you go, “go with all your heart”

In a larger sense, we, too, acknowledge the cyclic nature of life in this world, as does the medieval poem Piers the Plowman, with its famous phrase: “for pilgrims are we all. ” Whether we define ourselves as spiritual seekers or not, all human beings are sojourners on this planet, in motion ... just like a medieval pilgrim on the road to Compostela. We are all “on the road.”

Statue of the troubadour and writer Wolfram von Eschenbach, best known today as the author of the medieval Grail romance Parzival. He is portrayed with his harp, in the modern-day town square of Wolframs von Eschanbach, Germany, his birthplace, an area popular with modern-day visitors and pilgrims. Long-range view. (PJ Mally)

Global Peace Globe sculpture at Norwich Cathedral. (David Kelf)

Certainly by the mid-fourteenth century, a new literature was emerging in England, in which the language began to be used in more innovative ways. Piers the Plowman is a huge allegorical work; it first appeared around 1360. Copied extensively, it was evidently well-known by all classes of people. In the mid-14th century, “lines from it were used as slogans and signals in the so-called Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Poetry was alive and dangerous.” (38)

Rather than intellectuals or those in more traditional posts of power, the bardic Imagination, pilgrimage and travel—sacred or secular—is key to exploration. Music, poetry, and the arts are also stimulated by travel, as I have learned. For example, a favorite place to visit for modern musicians and others interested in the late medieval period is the statue of the troubadour and Grail romance writer Wolfram von Eschenbach, in his hometown in Germany. Modern cathedral directors have made efforts to attract contemporary pilgrims by incorporating creative concepts such as the opportunity to light a candle on the metal Global Peace Globe sculpture—a project for the good of the world in general, rather than just one church—at Norwich cathedral in England.

Our earth ... and Compostela, the “field of stars”

The words of one contemporary pilgrim, the Brazilian writer Paul Coehlo, may also ring true. In 1986, he decided to walk along the Camino, to follow in the tradition of the “road to Compostela.” At a key juncture in his life, he wished to do more personal reflection. He went to France and began his journey from Saint-Jean-de-Port to Santiago, like countless pilgrims of old. He walked through the steep Pyrenees and into northern Spain, crossing over many miles, finally ending up in Santiago de Compostela. He chose to take responsibility for his quest and his life, as many others along that path have for a very long time.

Coehlo comments about his own journey to Compostela, “the field of stars” and the shrine of St. James in our modern secular age.

Going on a pilgrimage reawakens ... awareness, but you don't need to walk the road to Santiago to get the benefits. Life itself is a pilgrimage. Every day is different, every day can have a magic moment ... But we are all on a pilgrimage whether we like it or not ... because in the end, the journey is all you have. (39)

Wolfram von Eschenbach statue, in silhouette, late afternoon sun, with a close-up view of his harp. Modern musicians have described returning from visiting the birthplace of this troubadour as a transformative experience. (PJ Mally)

The shrines of the Black Madonnas, too, have been identified as symbolic of potentiality, of creation in divine perpetuity, that which “is always in motion.” (40) The idea that we are always “becoming,” forever renewing ourselves, when on a pilgrimage is a potent one; the travel “that never truly ends,” even long after returning home, remains with us still. We are perpetually becoming, as we journey on in Life.

As above, so below

Every day is a new pilgrimage all its own, a metaphorical journey of life, regardless of one's beliefs, what you do, or where you may live. While a medieval pilgrim was required to get to a very specific, final destination, Life occasionally requires us to just let go of desiring a fixed result. Contrary to the demands of much of modern society, by learning to simply surrender to the Infinite and trust the process, we often find ourselves exactly where we need to be—consciously or not. We are always changing—in a process of perpetual “becoming,” forever renewing ourselves throughout our lives. Travel is an important step along the way; indeed, upon our return we may never be the same again. May we all journey well.

Winged Pegasus statue, Powerscourt estate, south of Dublin, Ireland (Karen Ralls)