Gothic Cathedrals: A Guide to the History, Places, Art, and Symbolism (2015)

CHAPTER 1

GOTHIC CATHEDRALS:

Architectural Gems in Stone

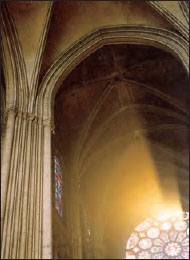

Chartres Cathedral, interior view of the incoming infusion of light into its haunting, dark Gothic interior (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

Our journey begins ...

Some years ago, the setting sun revealed the silhouette of the tall, darkening spires looming before me. Slowly, like untold numbers of travelers, I climbed my way up the steep cobbled village street to finally view this legendary Gothic cathedral—Chartres—whose legacy of exquisite architecture, art, ancient crypt, and expert craftsmanship was now a tangible reality. Centuries of history, the inspiration of guilds, artisans, and all those who had walked this path and lived here from ancient times, now intersected at this site. Observation of the meticulous medieval building techniques, too awesome to truly contemplate in our own age, the infusion of brilliant light of its Rose windows, and an encroaching awareness of the vast power of time and place filled me with wonder. With the faint sound of musical chanting wafting on the breeze, I became acutely aware of the rhythm of each footstep and its strong connection to the earth below as I approached the towering edifice before me. A gnarled old man's hand from within unbolted its lock and opened the huge heavy door, beckoning me to enter ....

I crossed the threshold.

Into another world. Unexpectedly intrigued upon initially encountering a rather dark interior, like many travelers before and since, I was here to explore and experience this place, to discover a genuine “architectural gem” of its time—Chartres cathedral.

A site of many wonders, it has been dubbed an omphalos, a navel of the world.

Lux Lucet In Tenebris, “Light shines in darkness”

Light is the symbol of truth, hidden wisdom, and a higher understanding beyond all human division, definition, and activity. Allowing in light from out of darkness was a key theme of the new Gothic style that emerged in the twelfth century; the art and beauty of Gothic cathedrals still captivate the hearts and minds of visitors worldwide. Such visitors include those who are spiritually inclined from many traditions, religious believers of all faiths, as well as secularists, atheists, and agnostics.

At Notre Dame de Paris, an evening candlelight interior view. (Karen Ralls)

Saint-Denis: the first Western Gothic building

The first Gothic building in western Europe—Saint-Denis in Paris—was an extraordinarily experimental project, architecturally courageous, and emerging quite suddenly. It was completed in 1144. Ironically, it was not a large cathedral, but an ornate, smaller Gothic choir that was added to the existing abbey church at Saint-Denis. Yet its Gothic basilica was done in a totally new style; its unusual features and beauty stunned nearly everyone present at its unveiling—with its pointed arches, bejewelled stained glass windows, and other unique features never seen before.

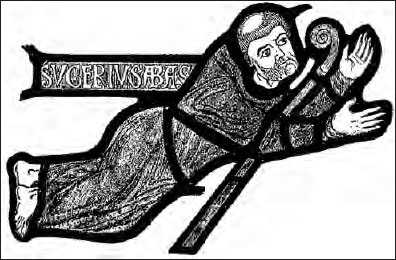

Abbot Suger (c. 1081-1151) was a French ecclesiastic, statesman, and historian. (WMC)

The chief architect Abbot Suger, along with the talented stonemasons and other guild members on his team, wrote of his overall vision and intention, describing what he called Lux continua—“continuous light.” He insisted that the key meaning of this bold, new design was luminosity: “Bright is the noble work; being nobly bright the work should brighten the minds ...” (1)

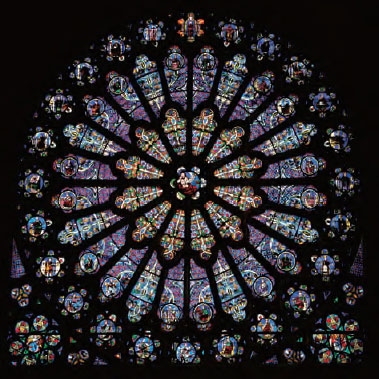

The north transept rose window at Saint-Denis was constructed c. 1250, and features a genealogy of Christ in the form of the Tree of Jesse. (Oliver Mitchell, WMC)

Letting in the light was paramount. Many believe that Gothic design creates a unique environment where a visitor or pilgrim may experience the numinous within the material world—a spiritual nexus point, a crossing of two or more dimensions simultaneously.

After the initial work at Saint-Denis, other twelfth century Gothic marvels would soon follow, including Chartres, Notre Dame de Paris, Amiens, Canterbury, York, Bayonne, and others.

What, then, is a medieval Gothic cathedral to our 21st century mind's eye? Why, as Umberto Eco wrote in a famous essay, are we in the West still “dreaming the Middle Ages” in our modern world? Why is that era from so long ago still so captivating today?

Let us explore the architecture, design, and wonders of Gothic cathedrals—those often hauntingly dark interiors welcoming the incoming light through their famed Rose windows. With their often equally beautiful outdoor grounds and gardens, the Gothic spirit embodies the ancient and medieval principle: Lux Lucet In Tenebris, “Light shines in darkness.”

WHAT IS “GOTHIC”DESIGN?

What, then, is actually meant by the term “Gothic” architecture? From popular images of elusive monks working in darkened cloisters in novels like The Name of the Rose and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, to medieval imagery in films, or the glossy guidebooks of Chartres or Canterbury, Gothic cathedrals continue to inspire, enchant and intrigue. People from all over the world and all walks of life visit these sites, and often greatly appreciate their stunning design, aesthetic beauty and cultural importance.

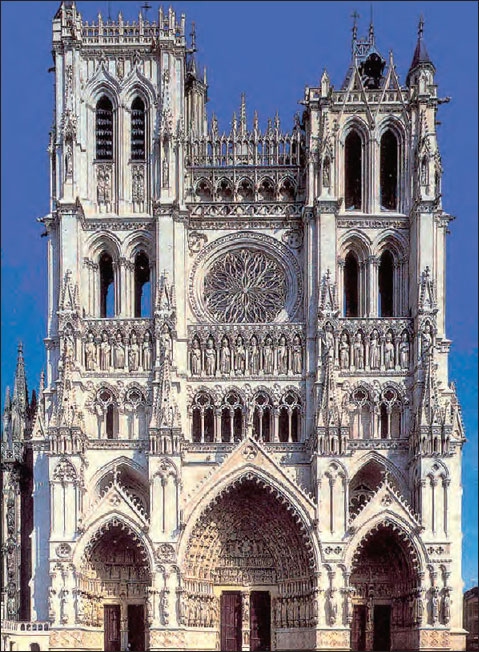

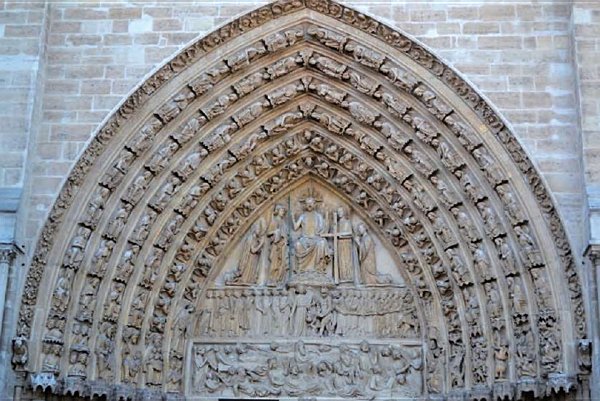

“Gothic” is known to us today as the name for a special medieval architectural style that featured high naves, flying buttresses, pointed arches, rib vaulting on the ceilings, stained glass windows, and intricate stone carvings. (2) Yet a great irony is that the term “Gothic” actually pertains to the Goths, a northern people, who had nothing to do with this kind of architecture. Of course, the word “Gothic” today also means something intriguing, dark, or especially mysterious—perhaps not unlike how one might feel when entering a cave, an ancient site like Newgrange, or the Hypogeum in Malta, or, when crossing the threshold into Chartres. Examples of Gothic architecture range from the majesty of Canterbury, York, or Wells, the glories of Chartres and Amiens, the beauty and unique “philosopher's carvings” of Notre Dame de Paris, and many other sites in Europe.

Amiens Cathedral, exterior view of its triple entrance door and tympanum. (Karen Ralls)

Bayonne Cathedral nave, interior view, looking upward. (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

Notre Dame de Paris, view from the southeast. The cathedral was memorialized in Victor Hugo's Hunchback of Notre Dame. It was the site where the charges against the French Templars were read out in 1307. (Skouame, WMC)

What is it about these buildings that is especially unique and captivating, and why do they seem to have such powerful effects upon visitors to this day?

The High Gothic style is especially noted for its focus on “upward” orientation, tall naves, and its emphasis on letting in much light—something very different from the previous Romanesque style, which featured round arches. (3) The entire Gothic cathedral design tends to give a visitor or pilgrim an overall impression of soaring upwards, of being “lifted up,” from its roots in the very depths of its crypt, as well as an impression of the drawing down of light into the building. Gothic cathedrals were seen by their medieval designers as houses of light dedicated to the Glory of their God, the epitome of a celestial paradise on earth.

Yet, Gothic cathedrals also exhibit rather unusual characteristics and carvings, inexplicable details that would appear to be based on much earlier philosophies from the ancient world. These seem to have been assimilated and/or re-worked by the Western Church and found their way into Gothic designs.

Notre Dame de Paris, entrance, looking upward at the carvings on its Tympanum (Karen Ralls)

The newly emerging “Gothic” style mushroomed virtually overnight

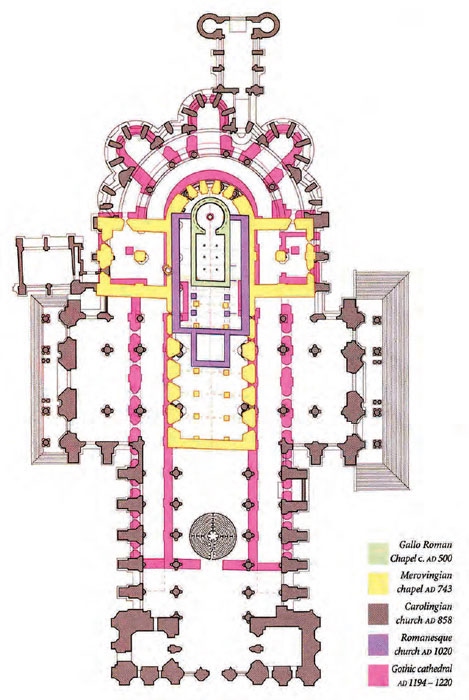

Appearing nearly overnight, the new Gothic style caught on quickly, beginning in France in the late 1130s and ending in the early Renaissance, when a preference for more classical designs returned. As mentioned, the extraordinary flowering of this new twelfth century style began under Abbot Suger in the Benedictine church of Saint-Denis (1130/1135-1144) in Paris, the burial place of many French monarchs. (4)

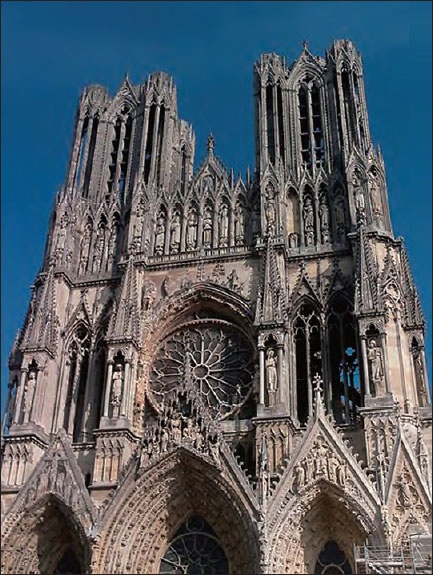

After the middle of the twelfth century, the cathedrals of Noyon, Senlis, Laon and Notre Dame de Paris also began to express this new Gothic style. By the beginning of the thirteenth century, Gothic architecture had reached its mature form in the cathedrals of Chartres, Reims, Amiens, and Bourges, later (from 1231) reaching a climax with another major project: the conversion of the larger abbey church of Saint-Denis. Other examples of the new Gothic style would follow, such as the stunning royal palace chapel of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, the cathedral at Troyes, and the royal castle chapel of Saint-Germainen-Laye.

Salisbury Cathedral, view of its nave, looking west, (Raggatt2000, WMC)

The Cistercian order in Burgundy, founded in 1098, also contributed to the rapid spread of the Gothic style in France. (5) (In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the powerful Cistercian Abbot, Bernard of Clairvaux was instrumental in assisting the fledging Knights Templar Order with obtaining the necessary papal approval in 1128/9. Bernard wrote that God was “length, width, height and depth.”)

While France was the “motherlode” of Gothic design, (6) other countries in Europe gradually began to follow suit. In around 1180, the Gothic style spread first to England (Canterbury, Wells, Salisbury, Lincoln Westminster Abbey, and Lichfield) (7); then to Germany (Marburg, Trier, Cologne, Strasbourg and Regensburg from 1275); and on to Spain (Burgos and Toledo). (8) Styles of Gothic could vary in each country. In England, for instance, there were different stages of Gothic design. One was called the Perpendicular style, a rather ornate one which emerged later. Examples include the especially ornate ceiling at Gloucester cathedral in the east walk of its cloisters, and at Exeter cathedral which portrays the emphasis placed in earlier English Gothic on its thick walls. (9)

The Romanesque Style

The Roman Empire had made extensive use of geometry and the semicircular arch in its building designs. Many churches, right up to the time of the first Gothic cathedrals, featured these round arches and beautiful, ornate carvings and columns. This style was known as “Romanesque.” (10) The great Basilica of Vezelay, dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, was one of the favorite shrines of medieval pilgrims. It remains one of the most popular French examples of the beauty of the Romanesque style today.

But new innovations followed in the twelfth century. These included the hallmarks of Gothic design innovation such as the introduction of the pointed arch. The flying buttress was another. Located on the sides ofcathedrals, they were designed to support the great weight of the tall Gothic buildings. The cathedral could “soar higher” while the flying buttresses helped to support the added weight that the pointed arch aesthetically transferred from above. Architecture is as much a science as an art. We will explore more of the complex mathematics and physics of the design and structure of these extraordinary cathedrals as we proceed.

Salisbury Cathedral, west front view, (Raggatt2000, WMC)

The new “Gothic” style greatly disparaged by the Renaissance critics

It is not often realized today that the term “Gothic” was initially used in a disparaging way by early Renaissance critics of the newly-emerging style. They abhorred its lack of conformity to the earlier standards of classical Greece and Rome, which they preferred. Ideologies change, regimes come and go, and this includes architectural styles. (11)

A closer look, however, reveals that the medieval architects who built the Gothic cathedrals were firmly rooted in great awareness and careful application of geometry and proportion. Two aspects of Gothic architecture “are without precedent and parallel: the use of light and the unique relationship between structure and appearance.” (12) This is seen in the overall cruciform shape and plan of the cathedrals; in the rhythmic, intricate patterns found in stained glass windows; and in the rib vaulting that criss-crosses the ceiling. (13) But many variations in design occurred within the definition of what was called “Gothic,” and each European country or region had its own special characteristics.

Unfortunately, contemporary medieval attitudes to Gothic architecture do not emerge clearly from the written sources. There was no continuous tradition of writing about visual arts during the 11th—13th centuries, leaving historians with relatively few records to pore over today. So to really understand these exquisite edifices, it is often more a question of doing a “symbolic reading” of the building itself and its visual carvings and symbolism, rather than merely relying on information from written sources or guidebooks.

The medieval mind was preoccupied with the symbolic nature of the world of appearances, as everywhere “the visible seemed to reflect the invisible.” (14) Imagination was paramount; the intuition was highly valued. But first, let us consider the overall cultural milieu that spawned the Gothic experiment. Building a cathedral was not merely a “church-only” enterprise, as many might assume today.

Plan and building stages of Chartres cathedral through the centuries. (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

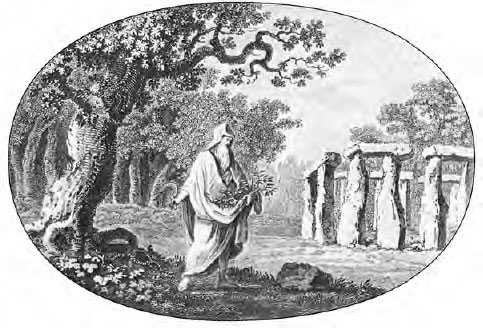

Early depiction of a Carnute Druid grotto in Gaul. The area of, and around, Chartres in earlier times was known to be a major assembly meeting place for Druids; the town of Chartres derives its name from the tribe of the Carnutes.

HOW THE CATHEDRALS CAME TO BE BUILT: A PROJECT FOR ALL

So what kind of a society were the cathedrals part of, and what was the planning process that brought them about? We know that the structure of medieval society was a feudal one—often very difficult and repressive, and certainly hierarchal, with the Church envisaged at the center. The entire medieval period lasted for well over four centuries, with the High Middle Ages within it generally thought to be from 1100 to 1300, although historians continue to debate a precise dividing line.

Some people assume today that the Middles Ages were entirely negative times—utterly barbaric, lawless and/or horribly oppressive, and that only ignorance and superstition reigned. But is this singular, stereotypical image of the Middle Ages accurate? No, as no period in history is ever only one-dimensional. In fact, it was a highly complex time, with many threads to its historic tapestry.

Although most people could not read, including a number of monks, philosophy and learning itself were quite advanced in some areas in the late Middle Ages. Medieval Paris, for example, was one key location where the very roots of what became the Western university took shape. (15) For various reasons, during the later Italian Renaissance, what might be termed today as a negative “spin” on the entire preceding Middle Ages period, fostered some misconceptions about medieval times that have survived to the present day.

Looking at a Gothic cathedral, we note that every walk of life is portrayed in the art and decoration of the structure. (16) Although the society itself was very hierarchal, not only were kings and clerics portrayed in carvings or stained glass windows, but so were peasants, merchants, craftsmen, even jesters. A wide range of everyday medieval life activities are portrayed, with individuals from every rank of society included, images that we might not necessarily expect to see today in a medieval building. For example, at Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, some of its stone carvings show peasants hauling winter fuel; at Florence, peasants are seen with plough, horse, and cart upon the entry to “Giotto's Tower”; at Bourges, the coopers ply their trade; at Chartres, the stained glass windows portray medieval guild tradesmen busy in their workshops, and among the sculptures at the left door of the Royal Porch, we see a peasant harvesting grain; and kings adorn the west front of Wells Cathedral. (17). Everyone in the medieval community was seen to have made an important contribution to the building, and the patrons and guilds who sponsored certain windows or carvings ensured that their activities were beautifully portrayed.

General structure of medieval society

Many theories abound about the structure and organization of medieval society, with a number of historians and those from many other disciplines continuing to further explore, challenge, and debate this vast topic. The usual image has long been that of a rigid pyramid scheme.

In his classic early work The Ages of the Cathedrals, French Professor of History Georges Duby explained that in general, medieval society was structured like a pyramid, with God at the very top. Next were the saints. (18) In the popular view, the saints were largely seen as alive, active, intensely interested in mortal affairs, each having his or her own local cult center, with the power to intervene for the protection of their subjects, having a miraculous power to help their own, sometimes quite dramatically.

St. Pauls Cathedral, London. This key ancient site has an interesting history with Ludgate Hill and remains a major attraction. (Simon Brighton)

Below God and the saints, according to Duby, the hierarchy of medieval society was largely split into two broad divisions: one was the ecclesiastical—including the pope and bishops at the top, abbots and monks, archdeacons, cathedral canons and other functionaries; the second included the secular leaders—starting with kings and emperors at the top, then princes and barons, knights and gentry, merchants and artisans. (19) Finally, there were the peasants, many types of travelers, and others. Such was the medieval Church's general mindset at this particular time in Western history. Today, many more aspects of this topic continue to be debated and explored.

On the whole, Gothic cathedrals were intended as centers to be used by all levels of society—not merely for the churchmen, clergy, nobles or kings, or even just those attending a service in the cathedral. Their consistent usage was intended for highly sacred as well as certain secular purposes at various times throughout the calendar year.

St. Paul's Cathedral, London, looking west. (Simon Brighton)

Gothic design initially “suspect” and “highly controversial”

A supreme irony of history is that the very suggestion of a dramatically new concept or idea—in this case, the development of the new style of Gothic architecture—is often initially viewed as heretical or anathema. Gothic design was no exception, as initially it was highly controversial to many and considered “a heresy.” It only gradually obtained acceptance and solid ground later.

Some of the learned late medieval and early Renaissance opponents of Gothic architecture, phrased their displeasure as “what we now vulgarly call the Gothic”—a derogatory, if not downright insulting term. (20) Similarly, others, especially writing from Italy, felt that this new style was positively “decadent”—often heatedly debating on precisely who was to blame for this new, “barbarian” style. Filarete, for example, who lived from about 1400 to 1469, commented in one of his learned architectural treatises that “cursed be the man who introduced ‘modern’ architecture.” “Modern,” of course, referred to the groundbreaking Gothic style! (21) Clearly, the High Gothic style made more than a few waves in certain quarters.

A noted British medieval architectural historian once stated that “even though this period is still characterized in all seriousness as the age of cathedrals, the most characteristic building of the Middle Ages was not the cathedral, or even the castle, but the hall. The hall was the basis of domestic dwellings, barns, hospitals, shops, and markets. It was an essential element of more complex assemblies of buildings such as castles, colleges, or monasteries....” (22) Halls and barns, too, were important. One extraordinary example is from Cressing Temple, in Essex England. Its huge wooden Wheat Barn was built by the Knights Templar in approximately 1260 CE. (23) At this time, the Gothic style was supposedly at its zenith. But the Barn represents a more familiar setting for the populace of the everyday experience of people and architecture in late medieval life—far more so than a major cathedral like Chartres, Wells, or Salisbury. “[T]he exclusion of secular buildings has strongly affected the historiography of late medieval architecture.” (24)

Today, we tend to see the Gothic style as the “main type” of medieval building design, and often envisage Gothic cathedrals as “mainstream” for the late medieval period. Ironically, this popular view ignores the great controversies that were associated with its initial emergence, and the dramatic and revolutionary creativity of the style. Our modern idea is quite the opposite of how the style was initially perceived when it began. (25)

The Presence of the Saint

At the beginning of the history of Gothic design—before it was the usual practice to break up a cathedral into smaller compartments with lofty screens, and so on—it was strongly believed that the most permanent inhabitant of a great cathedral was its resident saint, the one whose shrine dominated the building. The architecture of a cathedral was seen as creating a ritual setting, with a saint's shrine as a key focal point. (26)

The importance of the saint to the devout in medieval times—whose physical presence was unquestioned because his or her relics were kept in precious reliquaries on site—cannot be overemphasized. The extraordinary lavish craftsmanship of the reliquaries speaks volumes, as does the focus in cathedrals on saints' shrines for pilgrimages—all of which we will later explore in more detail.

At Canterbury Cathedral, for example, the whole design was re-envisioned as a great tribute to, and the home of, St. Thomas à Becket. His shrine is still popular. Canterbury was dedicated to Christ Himself, and no mortals could claim it as their home in quite the same way in which it was seen to be “Christ's and St. Thomas.” (27)

The Cathedral as a Community Center

As some cities had no town hall, a cathedral was also often viewed as the key meeting place for use by every order of society: from peasants, merchants, and minstrels to the clergy, bishop, or king. Practically speaking, it often operated as a type of medieval central “community center,” designed to provide a venue for both sacred and secular functions—a concept rather uncommon at the time. The interior of a major Gothic cathedral was intended to have an overall design large enough to accommodate everyone under the same roof at any one time.

There were many public holidays in the medieval calendar. Most were connected to various saints—in fact, in some areas, the medieval Church insisted on 70 or 80 a year (although certain feast days could get quite lively to the chagrin of much of the clergy!). At times, the cathedral served as a center for colorful pageants and dramas. The role of merchants and artisans in the High Middle Ages was not a secondary one by any means. The town cathedral often served as the site of a lively merchant's or civic meeting, a solemn or joyous religious service, or, for the purpose of providing sanctuary for the community in times of trouble, danger, and war.

For the general populace, the cathedral may have often seemed like a rather distant vision at times. But when it was being built, they were consulted, and were also able to find reliable, steady work there. In the building of Chartres Cathedral, for instance, everyone at all levels in the town and diocese, and of the region or country around it played his or her part—including the king. (28) People might contribute something, according to their resources, to the cathedral building project or fund. When the building was finally finished, they were allowed to join with the priesthood on Whit Sunday for the great processions into the cathedral. They were also allowed to attend major feast days and prestigious processions—a real privilege at the time. Or, they might choose to go as pilgrims to cathedrals elsewhere on the feast days of the saints who were buried there. (29)

A noble or wealthy layman was also an occasional visitor to the cathedral. Such a man had probably endowed charities to help finance the cathedral in order to help save his and his family's souls after death. When he came to the cathedral, he might find, as at Autun, a stirring reminder of the Last Judgment to greet him over the west portal; or, as in the Pardon Cloister at Old St. Paul's, a dramatic representation of the Dance of Death. This iconographic tableau was a major symbol in medieval times, reminding all of their ultimate mortality in this earthly life—a key idea in the High Middle Ages. However, in spite of their legendary pomp, such “great men” were also expected to gather under the same roof for the same feasts or processions as the rest of society.

In summary, Gothic cathedrals were intended for multiple use by society—the masses of ordinary, hard-working people, as well as the kings and bishops. But, their most important purpose was to house their most treasured inhabitants after God and Christ Himself—the saints. There was a price to be paid for this, however. Cathedrals were very expensive to build, a public process that lasted for years. In certain locations, a cathedral tax was levied on the townspeople. When this was attempted in France, where towns were independent of the cathedral, “the townspeople rioted if the tax became too high,” (30) reminiscent of tax riots in some European countries in more recent times. So when we visit the aesthetic glories of the Gothic cathedrals today—while aware of the pleasures the cathedrals provided the community—we should also remember and appreciate the price all of the people had to pay for these medieval marvels. (31)

Notre Dame de Reims, exterior approach, looking upward at its majestic spires. (Karen Ralls)

The stones speak ...

Architectural historians have learned much about how Gothic cathedrals were actually built by examining precise details of the structures themselves. They have been able to study the more public parts of the cathedral where everyone would congregate, such as the interior, the nave, and so on. And they have been able to access the lesser-known, more private sections of the cathedral building complex as it would have been seen from the standpoint of an experienced medieval builder.

Gloucester Cathedral, England, view of cloisters corrider and its stunning stained glass windows. (Karen Ralls)

John James, a local expert in medieval building techniques and history, in his study on the master masons of Chartres, points out:

Truly, the stones themselves do speak. The staircases that the masons used for access, the rooms under the towers, the walkways around the outside and in particular the attic rooms behind the triforium passage are the builder's territory. It is here, in these unlit and seldom visited spaces, that the answers are to be found. And it is as unexpected as it is clear, once understood... (32)

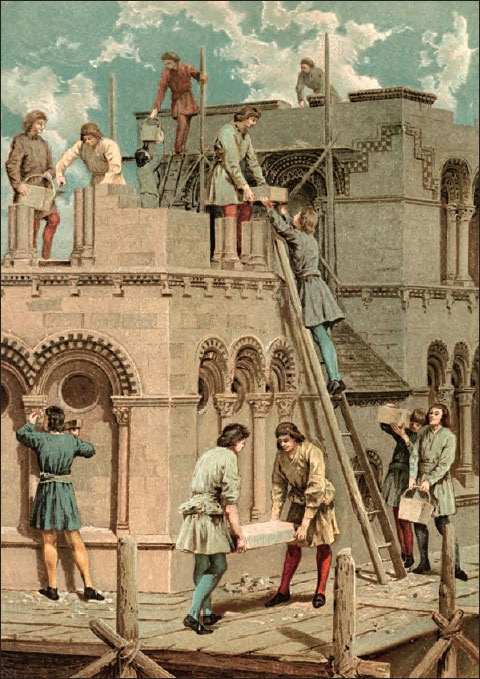

Medieval Freemasons at work. (Albert Mackey, Illustrated History of Freemasonry)

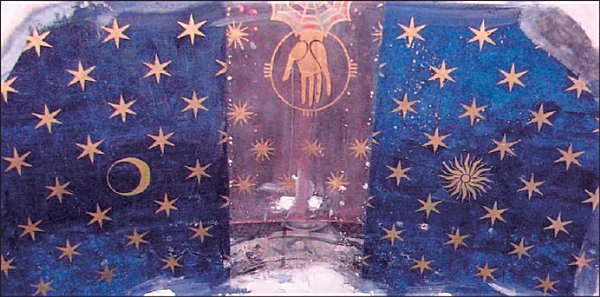

So it was in this unique climate, covering elements of both the obvious and the hidden, that the cathedrals came to be built. The upstairs nave and its features, as many have noted, are stunning. But the lower levels, crypts, and undercrofts of some of the key Gothic cathedrals also feature excellent artwork, ornate shrines, or paintings, such as the colorful, interesting mural, Black Madonna statue, or ancient well in the crypt of Chartres cathedral. “As above, so below.” Both the upper and lower levels of a cathedral feature an array of high quality worksmanship.

We know the later medieval society that developed the Gothic style, while rigidly feudal in organization, was no longer quite as overtly tyrannical and arbitrary by the late High Middle Ages period as in the earlier medieval era, the so-called “Dark Ages”—a popular, generalized, stereotypical term that, thankfully, has now become largely outdated and obsolete in many quarters. Ironically in the High Middle Ages, because people had a chance to work on the construction efforts (either for pay or as volunteers), they at least did have access to the more private areas of their cathedrals. Contrast this with modern building projects, where only the head architects and their skilled staff usually have primary access.

View of Chartres cathedral crypt mural, prior to its recent restoration. (Karen Ralls)

As we mentioned earlier, the cathedral was often a town's sole focal point—its central secular civic center, a place to escape from a day's drudgery, as well as for worship, sacred ceremony, or pageantry. (33) That which occurred within a cathedral's nave during a typical medieval liturgical year was not always as predictable or conventional as we might expect. This was especially true on the major feast days—some of which could be quite creative, even outrageous, as joviality often ran rampant. Eventually, some activities were banned by the less-than-amused medieval clergy.

One example of this phenomenon would be the lively medieval festive seasonal celebrations of the “Feast of Fools,” to which we will now turn.