The Literature Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

FOCUS

Psychological realism

BEFORE

c.1000-12 Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji offers psychological insights into the lives of its characters.

1740 English writer Samuel Richardson’s sentimental novel Pamela explores the inner nature of the novel’s heroine.

1830 The Red and the Black, by French author Stendhal, is published and is seen by many as the first psychological realist novel.

AFTER

1871-72 George Eliot’s Middlemarch traces the psychological landscape of a provincial English town.

1881 The Portrait of a Lady, by US author Henry James, delves into the consciousness of the character Isabel Archer.

Psychological realism is the depiction in literature of the personality traits and innermost feelings of a character, casting a spotlight on their conscious thoughts and unconscious motivations. The plot itself often takes a secondary role in works that focus on psychological realism, and is there to set out the relationships, conflicts, and physical settings within which these mental dramas are played out.

Delving into the psyche of a character in this way marked a radical departure from Romantic fiction, in which plotlines typically saw wrongdoing punished and virtue rewarded. Literary works had, however, long explored the workings of the human mind, though uninformed by the emerging science of psychology. For example, mental machinations are central in the 11th-century Japanese story The Tale of Genji; in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1603), it is the inner conflicts of the hero that drive the drama; and the 18th century saw the heyday of the genre known as the epistolary novel, in which personal letters and journal entries were used to give the reader an insight into a character’s intimate thoughts and feelings.

"All is in a man’s hands and he lets it all slip from cowardice."

Crime and Punishment

Exposing minds

In his masterpiece Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky introduces the reader to his antihero, the student Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, also called Rodya or Rodka by the few people who love him. The author dissects - by means of a third-person narrative - Raskolnikov’s psychological motivations in a way that presages the work of Sigmund Freud and other psychoanalysts. It is precisely this opening up of the protagonist’s mind to the reader that secured the book’s status as one of the most important and influential literary works to emerge in the 19th century.

Crime and Punishment opens on a “hot evening early in July” in St Petersburg, Russia. Raskolnikov, a shabbily dressed young man, steps from his tiny, garret flat, skips past his landlady, and slips away into the heat and the stench of the city. He is ill and also suffering from some form of mental dislocation. He mutters to himself. He is hungry. He walks the streets, disturbed by the presence of others. The reader is drawn ever closer to his innermost thoughts, fears, and anxieties.

Raskolnikov is poor, and this motif of poverty is pervasive in the text. The reader wanders with him, seeing with his eyes a city that is striving to survive - a place in which many struggle against hunger and mental torment.

Summertime in St Petersburg is the setting for Crime and Punishment. The crowded, stifling conditions in the city mirror the troubled student Raskolnikov’s feverish inner drama.

Inner conflicts

Dostoyevsky inserts a variety of colourful and brilliantly observed characters into the narrative, as seen through Raskolnikov’s eyes. He ventures to the house of Alyona Ivanovna, a local pawnbroker, “a diminutive, withered up old woman of sixty, with sharp malignant eyes and a sharp little nose”. Raskolnikov has come to pawn his father’s watch and, poverty-stricken, he is forced to accept a pitiful sum for it. As he leaves the apartment block, a thought enters his mind. He stops on the stairs, shocked at himself, and once back on the crowded streets, he walks as though in a dream, “regardless of the passers-by, and jostling against them”, until he finds himself by a flight of steps leading down into a tavern. Although he has never been into a tavern before, he enters and orders a beer, and immediately “he felt easier; and his thoughts became clear”. But Dostoyevsky informs the reader that Raskolnikov is far from well, because “even at that moment he had a dim foreboding that this happier frame of mind was also not normal”.

He has a conversation with a drunken man, Marmeladov, who tells a pitiful story of poverty and his daughter’s prostitution, both brought about by his alcoholism. Marmeladov acknowledges his vice and reveals that he is confessing this to Raskolnikov, a chance encounter, rather than the regular patrons, because in his face he can read “some trouble of mind”. Raskolnikov finally returns to his own hovel where he broods all the following day. Dostoyevsky paints a desperate picture of destitution and Raskolnikov’s isolation from society.

The author’s mastery of psychological realism fully exposes Raskolnikov’s inner deliberations and machinations over how to act on his thought, which is to commit a crime (by killing the pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna), and he draws the reader tangibly and empathetically close to Raskolnikov’s mind - the mind of a murderer. We feel his terror, and we experience the dirty streets and depraved citizens of St Petersburg through his eyes. We become witnesses as scenes are played out in his mind, and we lie beside him in his squalid home. We, too, start to feel the awful sense of the inevitability of the act, from its imagined conception through to its grim and bloody reality.

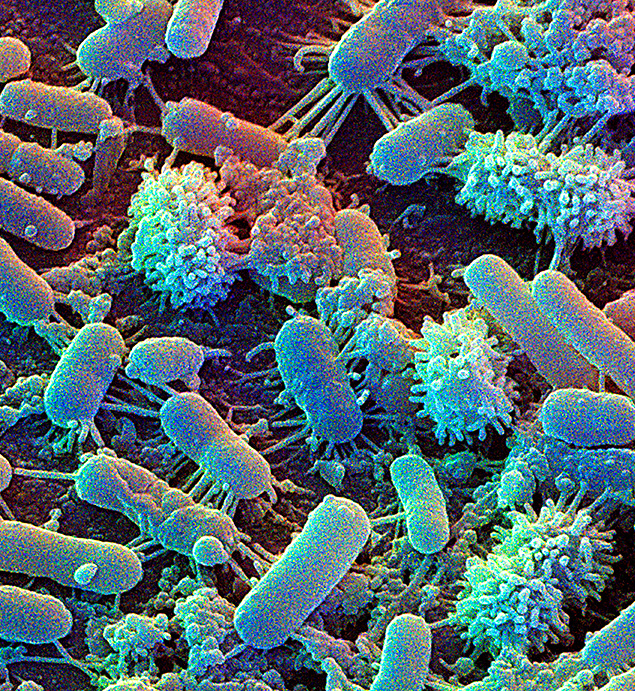

Just as Freud would later argue that dreams enable understanding of waking experience, Dostoyevsky offers insights into his antihero’s mind through his dreams. In one dream, Raskolnikov witnesses drunken peasants beating a horse to death. Heavy with symbolism, the dream foreshadows the crime he is about to commit, but it is also a reference to his desensitization to atrocity, and to the loss of his free will to act. Much later, he dreams that microscopic bugs cause insanity, dissent, and a propensity to violence in humans - an allusion to Raskolnikov’s state of mind.

"Only to live, to live and live! Life, whatever it may be!"

Crime and Punishment

Raskolnikov recalls dreams he had while delirious in hospital. In one a plague of microbes had infected people and driven them mad, all convinced that they “alone had the truth”.

The shock of violence

The murder of Alyona Ivanovna is portrayed with a powerfully visceral actuality. Raskolnikov clubs the old woman with an axe until her skull is “broken and even battered in on one side”. Over the floor lies “a perfect pool of blood”. The moments hang in chillingly real tension as Raskolnikov unlocks a wooden chest under the bed and retrieves the riches of “bracelets, chains, ear-rings, pins”. And the scene is not complete. There are further footsteps in the room where Alyona Ivanovna lies. “Suddenly, he jumped up, seized the axe and ran out of the bedroom”. So ends the first part of the novel.

Dostoyevsky presents several potential motives for this crime, the most prominent of which is Raskolnikov’s perception of himself as a “superman” - someone superior to others, above the law, who feels a disgust for society and the mindless behaviour of the herds of “ordinary” people. At one point, Raskolnikov remarks that all great men have been criminals, transgressing ancient laws and shedding blood if it were “of use to their cause”.

Dostoyevsky’s exposition of this motive is thought to reflect his anguish at the changes he observed in Russian society - the rise of materialism, the decline of the old order, and the popularity of selfish and nihilistic philosophies. Raskolnikov’s crime, and his later unravelling, serve as a caution to those of Dostoyevsky’s compatriots inclined to revolutionary change.

"The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth."

Crime and Punishment

Guilt and redemption

In the unfolding consequences of the murder, we follow Raskolnikov around the streets of St Petersburg in his desperation and fevered delirium. He stumbles upon the drunk, dying Marmeladov who has been run over by a carriage and horses, and is drawn closer to Marmeladov’s daughter, Sonya, who is left to support the family alone. Raskolnikov meets Porfiry Petrovitch, a detective who becomes increasingly convinced that Raskolnikov is guilty of the crime, but lacks the evidence to prove it. Raskolnikov’s nerves are in shreds. Would confessing and taking the punishment of the law be preferable to the torture of his own conscience? Does his sense of remorse suggest that he is ordinary rather than extraordinary?

Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia in 1861. The prostitutes found around St Petersburg’s seedy Haymarket area, a regular haunt of Raskolnikov, were predominantly desperate peasant girls.

Representing reality

In Crime and Punishment, Dostoyevsky masterfully explores and dissects the immensely complex nature of the mind of his protagonist. The novel’s powerful exploration of the meaning of life and the existence in the world of horror, evil, suffering, and brutality is matched by its examination of guilt, conscience, love, compassion, relations with our fellow humans, and the possibilities of redemption.

Dostoyevsky’s concern for representing the reality of the psychological processes in Raskolnikov’s mind ensured that Crime and Punishment became a significant touchstone for future novelists. This approach to writing coincided with - and was arguably influenced by - the rise of the science and practice of psychology. One of the late 19th century’s most psychologically attuned writers, novelist Henry James, was brother of the pioneering psychologist William. The existential writers of the mid-20th century, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, also owe much to the ground-breaking narrative form created by Dostoyevsky.

Raskolnikov’s motives for killing Alyona Ivanovna are a central theme of Crime and Punishment. Dostoyevsky shows that his antihero’s actions are prompted by a complex interplay of motives, internal dialogues, and unconscious drives that combine social, individual, philosophical, and religious imperatives.

"A hundred suspicions don’t make a proof."

Crime and Punishment

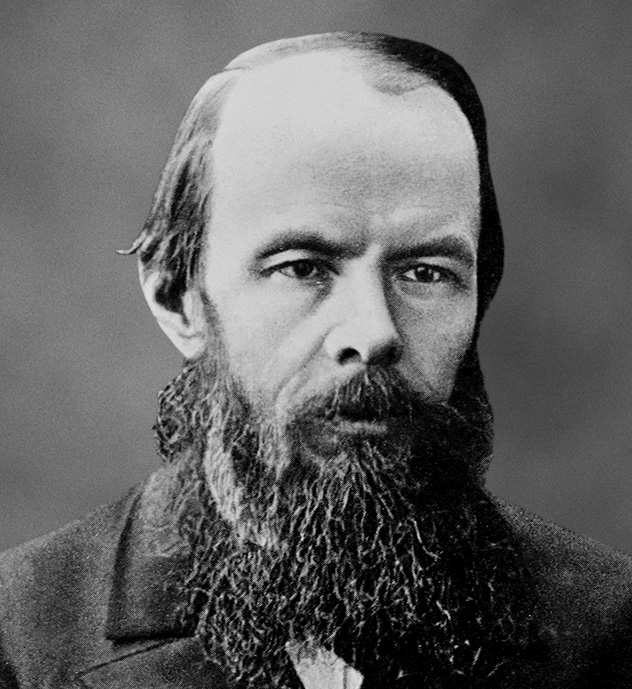

FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY

Fyodor Dostoyevsky was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1821 to parents of Lithuanian descent. He trained and worked as an engineer before writing his first novel, Poor Folk (1846), which depicts the mental as well as the material condition of poverty.

In 1849, Dostoyevsky was arrested for being a member of the Petrashevsky Circle, a socialist intellectual group. After the torment of a mock execution by firing squad, he endured several years of hard labour in Siberia, where he began to suffer from epilepsy. After his release, issues with creditors prompted his voluntary exile in western Europe. After the death of his first wife, in 1867 he wed Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina, who gave birth to their four children, acted as his secretary, and managed the family’s finances. Haunted by infirmity, he died in 1881.

Other key works

1864 Notes from the Underground

1866 The Gambler

1869 The Idiot

1880 The Brothers Karamazov

See also: The Tale of Genji ✵ The Princess of Cleves ✵ Madame Bovary ✵ Middlemarch ✵ The Portrait of a Lady