Dive Atlas Of The World: An Illustrated Reference To The Best Sites - Jack Jackson (2016)

THE RED SEA

Introduction by Jack Jackson

THE RED SEA IS A LONG, NARROW STRIP OF water which extends from the Gulf of Suez in the north-northwest to Bāb-el-Mandeb (the gate of tears) in the south-southeast. At its southern end it joins the main Indian Ocean via the Gulf of Aden. Covering an area of 438,000 sq km (169,000 sq miles) it is the northern end of the rift valley and is still evolving as the African and Arabian tectonic plates move apart at a rate of just over one centimetre (half an inch) per year.

The seafloor of the Red Sea has two principal features: a broad, smooth continental shelf and a deep axial trough, which is further split by an even deeper trough some 25km (15 miles) wide.

Volcanic activity where the seafloor is spreading, isolated topographic depressions filled with geothermal brines in the central and northern Red Sea and evaporation due to high temperatures and low rainfall have produced some of the hottest and most saline seawater in the world. This has led to prolific coral growth much further north than would normally occur, a rich ecosystem that has over several hundred species of coral and almost as many fish and invertebrates as Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Only 350km (217 miles) east-west at its widest point and less than 160km (100 miles) wide in places, there are almost no tides. Currents are mainly the result of density gradients in the water column. The maximum tidal range in the north reaches 0.9m (3ft) on spring tides, but in the central Red Sea there is hardly any tidal movement at all. For much of the year the prevailing winds are from the northwest and in the central Red Sea wind-driven seasonal changes and evaporation in summer have the most effect on the water level.

It is one of the deepest seas in the world with depths reaching 3040m (9974ft). Between Port Sudan and Jeddah brine pools have been measured with a salinity of over 250 parts per thousand and a temperature of 60°C (140°F). This suggests that the brine is hotter than 100°C (212°F) when extruded.

The land next to the Red Sea is generally mountainous with a low, sandy plain, the Tihama, to the shore. The Sinai Peninsula separates the Gulf of Aqaba and the Gulf of Suez, which is connected to the Mediterranean Sea by the Suez Canal. The Strait of Tiran is the approach to the Gulf of Aqaba and the Strait of Gubal is the approach to the Gulf of Suez. Both experience heavy shipping traffic in tricky waters. As a result shipwrecks are common. The Gulf of Aqaba averages 1700m (5500ft) deep with drop-offs that descend to the seabed. The Gulf of Suez, with an average depth of 60m (200ft), has many islands in the Strait of Gubal, which also has active oilfields.

CENTRAL RED SEA

From Hurghada to Port Sudan on the west, and Jeddah on the eastern side, the general topography is of shallow, shelving fringing reefs, inshore islands with sheltered diving, and offshore reefs that descend into the depths. Boats plying these passages often come to grief. Further offshore, islands and reefs rise from deep water to the surface as walls or drop-offs.

The diving is well documented except for that in Saudi Arabia, which until recently was open only to Saudi Arabian nationals, scientists and foreigners with work permits. Tourist divers can now obtain packages to Saudi Arabia through sponsorship by local dive operators. The diving is good, though several areas along the coast have suffered sedimentation and blasting from construction and spear-fishing by guest workers from the Far East. Parts of Saudi Arabia are well protected and home to the largest number of Dugongs left in the Red Sea.

While Egyptian diving gets better as you go south, Sudanese waters north of Port Sudan have the best diving and largest species diversity of the Red Sea. Isolated coral atolls and pinnacles rise steeply to the surface from deep water, giving great wall diving among healthy corals, good visibility and large fish, including shoals of Bumphead Parrotfish.

SOUTHERN RED SEA

The Red Sea’s topography changes south of Port Sudan. The water becomes progressively shallower and often has a boulder-strewn sandy bottom with coral outcrops, where there is no drop-off or wall diving. Reduced visibility makes the fish harder to see and the corals are less prolific due to sedimentation. The seabed is actually rising, making the water even shallower and warmer. As well as the usual fish and invertebrate species common in the Red Sea there are beds of sea grass where one can still find Dugongs.

Dust in the atmosphere produces deep red sunsets along the Red Sea. These Sudanese shell-fishermen, sheltering in the lagoon at Sha’b Rumi, are preparing for evening prayer.

WHY THE ‘RED’ SEA?

The name Red Sea was handed down through history and we are not sure how it originated. There are various theories: the red rock of the mountains that surround it; the deep red sunsets; extensive blooms of the algae Trichodesmium erythraeum, which turn the sea reddish-brown when they die; and the historical name the Hebrews gave to the people of the trade routes south of Israel, who lived among red rocks, the Edomites, derived from the Hebrew word for red.

When the Greeks began documenting the then-known world, the land of the Edomites became the land of the Erythraen people after erythros, the Greek word for red. Later, when the Egyptians expanded south, their southernmost colonization was called Erythraea, modern day Eritrea. The Romans carried on the tradition by using the name Mare Rubrum.

Eritrea has a longer Red Sea coastline than Sudan and more than 350 islands. Over 200 of these are in the Dahlak Archipelago, though only four are inhabited. This archipelago was a marine park during Ethiopian rule and it is still strictly controlled. Some islets still contain antipersonnel mines, so it is inadvisable to venture ashore without a guide.

In Yemen, Djibouti and the straits of Babel-Mandeb, where the Indian Ocean sweeps into and out of the Red Sea, the visibility varies with plankton blooms, but the marine life is profuse and often shows subtle differences from that further north. The seabed becomes more volcanic, and the area around the Bab-el-Mandeb is known for currents and big fish. Baleen Whales are sighted in March and April and Whale Sharks are found in June. A very large nudibranch, similar to a Spanish Dancer nudibranch, but with four gills rather than six, is found at the volcanic islands known as the Seven Brothers (Les Sept Frères), also known as Les Isles du Sebbah or Sawabi.

WEATHER

Weather throughout the Red Sea is mainly hot and sunny, though in winter it can be cold at sea. Temperatures vary along its length. Egypt, Israel and Jordan vary from below freezing in the desert in winter to 45°C (113°F) in summer. From southern Egypt southwards, winter temperatures only drop to 20°C (68°F) at sea and rise to a humid 47°C (117°F) at sea, or a dry 50°C (122°F) in the desert in summer. Mountainous areas can experience brief periods of torrential rain. To the north there is little rain or coastal cultivation. Most of the rain drains into the desert, but in Sudan, Eritrea and Yemen, the normally dry riverbeds (wadies) can briefly turn into raging torrents.

Seasonal winds affect some regions’ weather and have much to do with uncomfortably short seas. In the north, one such wind, the Khamsin, blows hot, dry air from the south or southwest (the Northern Sahara desert) between February and May and often brings sandstorms. The name, Khamsin, is derived from the Arabic word for fifty, because it can last up to 50 days. In August, the torrential rains in the Ethiopian highlands that fill the Blue Nile and cause the Nile in Egypt to flood, extend to southern Sudan and cause haboobs. The prevailing north winds become squalls of Force 8 or more from the southeast through west. Sandstorms, even well out to sea, reduce visibility to a few metres.

MARINE LIFE

Sometimes called God’s Other World, the Red Sea is famous for its marine life. North of Port Sudan, luxurious growths of stony and soft corals abound with dark magenta species of Dendronephthya Soft Tree Corals. In the far north the reef fish are so used to divers that they almost pose for them. The sharks that made Râs Muhammad famous are still there, but there are so many divers nowadays that they remain deep during the day. Whale Sharks are often found in the Gulf of Aqaba.

All along the Red Sea, huge shoals of fish gather to spawn in the spring and shoals of different species of dolphin occur close to reefs where they can shelter in rough weather. As you go south, shoals of reef fish become more frequent and the offshore reefs teem with sharks. In Sudan, north of Port Sudan, pelagics become common - Manta Rays, Marlin, Sailfish, tuna, Doublespotted Queenfish or Leatherback (Scomberoides lysan), known locally as Shirwi, and huge shoals of migrating Pilot Whales. Massive groupers can still be found on offshore reefs. There are no sea snakes, but snake eels are found at Sanganeb and become more common as you go south.

South of Suakin you can see whales blowing on the surface in the distance. Closer to the Gulf of Aden there are more pelagics, including Spanish Mackerel. The stony corals are not too good, but soft corals flexing in the current shake off the sediment, and muck diving (see p197) is rewarding.

Despite being connected to the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea has only one species of clownfish, the Twobar Anemonefish. Species endemic to the Red Sea and nearby areas include the Yellowbar (Map) Angelfish, Arabian Angelfish and the Masked Butterflyfish, also known as the Lemon or Golden Butterflyfish.

ENVIRONMENT

What little industrial pollution occurs in the Red Sea comes from shipwrecks, a few oilfields in northern Egypt and ports that are widely strung out along its length. Construction at Sharm el Sheikh and Hurghada has been responsible for sedimentation, sewage and indiscriminate anchoring on coral reefs, but these problems are now being addressed. Due to the number of reefs, commercial fishing is not a large industry, although sharks are targeted at the southern end where sun-dried shark meat was a major food source for the poor long before shark fins became valuable exports for sharkfin soup. There have been a few incidents of armed piracy on the Yemen side of the Bab-el-Mandeb and also off Yemen and Somalia in the Gulf of Aden.

DIVING THE RED SEA

Recreational Red Sea diving began as land-based diving in Israel, northern Egypt, Sudan and what was then Ethiopia. Temperatures on land made winter preferable. Some northern areas have become package holiday destinations for sunseeking vacationers during winter. However, winter water temperatures in the north can be cold enough to warrant diving in a dry-suit and it can be cold in the wind out to sea. In summer it is hot on land, and water temperatures are more pleasant. Made famous by Hans Hass and Jacques Cousteau, the Red Sea can now be enjoyed by all.

The Yellowbar Angelfish (Pomacanthus maculosus) is endemic to the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Oman, Arabian Gulf and East Africa. Juveniles of this species have a completely different colour pattern.

Dendronephthya Soft Tree Corals vary in colour from deep magenta, through red, orange and yellow to white.

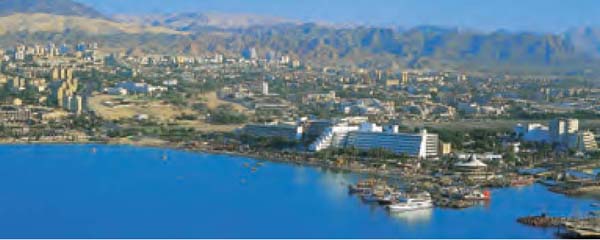

The main base for diving in Jordanian waters, Aqaba is near the ancient site of Petra, ’the rose-red city half as old as time’ and the ’Lawrence of Arabia’ scenery of Wadi Rum.

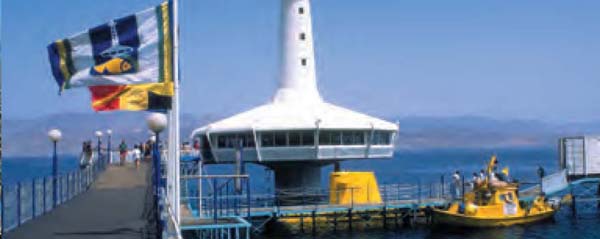

Eilat’s aquarium complex has a jetty out to its famous underwater observatory in the Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat). The yellow submarine takes passengers on underwater excursions.