Dive Atlas Of The World: An Illustrated Reference To The Best Sites - Jack Jackson (2016)

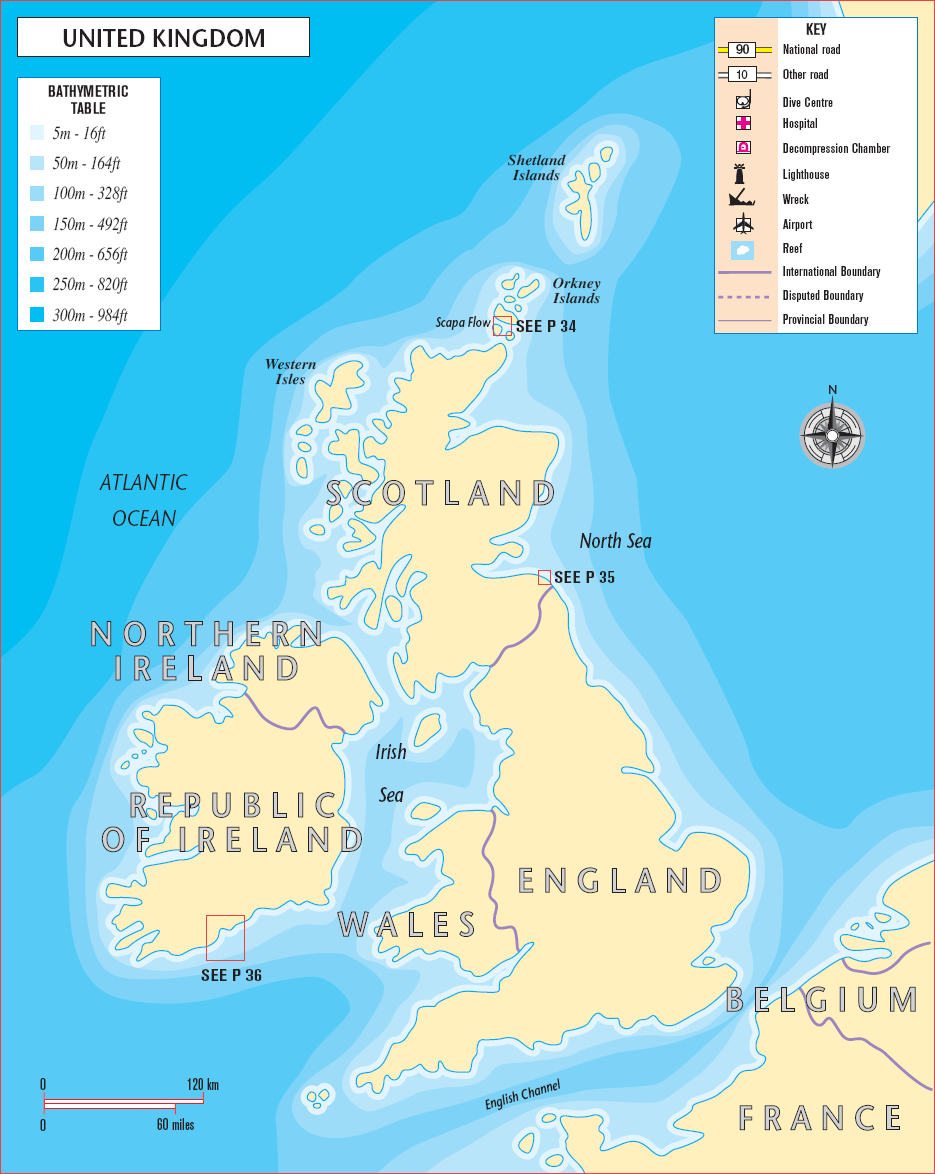

UNITED KINGDOM

Introduction by Jack Jackson

THE UK MAY NOT BE VERY LARGE AND ITS temperate waters are often murky, but it has plenty of interesting dive sites, a large number of shipwrecks and many divers who are keen to dive on them. In places with good conditions for bottom-dwelling organisms, sites are as colourful as their tropical counterparts. Beach dives, rocky gullies full of anemones, sea fans, crustaceans and nudibranchs, natural reefs, shoals of fish, kelp, seals, Fin and Minke Whales, Pilot Whales and other dolphins, various sharks and sea horses are all found in British waters.

To the west the warm Gulf Stream brings some surprising visitors including Ocean Sunfish and Leatherback Turtles. The whole western half of the UK sees basking sharks in spring and summer and sometimes these attract orcas. Ships pumping out ballast taken on in other climates and a slight warming of the waters has also enabled divers to find creatures that were not common here in the recent past.

Deep, cold water coral species are found off northern and western coasts and a reef built up by honeycomb worms has been found at 25m (80ft) off Dorset.

Wrecks are probably the most popular sites for those who dive in UK waters. With its rich maritime history of trade and war, the UK is littered with thousands of wrecks dating from Tudor times through to purposely sunk artificial reefs of the present day. During rough weather there is inland freshwater diving.

SCOTLAND

by Lawson Wood

Diving in Scotland is known for its clear water, abundant marine life and historic shipwrecks. Dives range from the easy, steep muddy slopes of the southern sea lochs to vertical and underhanging walls. Sea caves and underwater caverns sculpt the western and northern isles. Many of the islands and sea lochs offer challenging drift dives in formidable tidal streams. Most of the diving is done by boat, visiting offshore wrecks, reefs and shoals hitherto unknown to subaquatic exploration. For the most part - with the exception of a few popular wrecks - much of the diving can still be considered exploratory diving.

With an average tidal range of around 5m (16ft), and buoyed by the Gulf Stream, a large amount of water moves along some 10,000km (6000 miles) of coastline around hundreds of named islands and thousands of lonely, rocky stacks and reefs.

RESTRICTIONS ON DIVING ON MARITIME WAR GRAVES

There is a small minority of divers who cannot resist disturbing wrecks and the temptation of removing brass and other artefacts. Diving on deep wrecks has been facilitated by the introduction of technical diving for recreational divers and this has worried those still living who are connected with many who lost their lives in this century’s maritime military conflicts and disasters. In an effort to give greater protection to maritime war graves and military wrecks against trophy hunting, 16 wrecks have been designated Controlled Sites - where no diving is allowed without a special permit.

Most of the dives are far from convenient car parks, launching sites or towns and require considerable planning and backup. For that reason the bulk of the diving is carried out around a number of well-established commercial centres that have the combination of a good road and rail network, accommodation, slipways, air compressors and dive boats. Most coastal towns have dive clubs or at least dive club members. With these dive clubs you will experience more of the varied diving to be found. Over 60 per cent of all British diving takes place in Scottish waters.

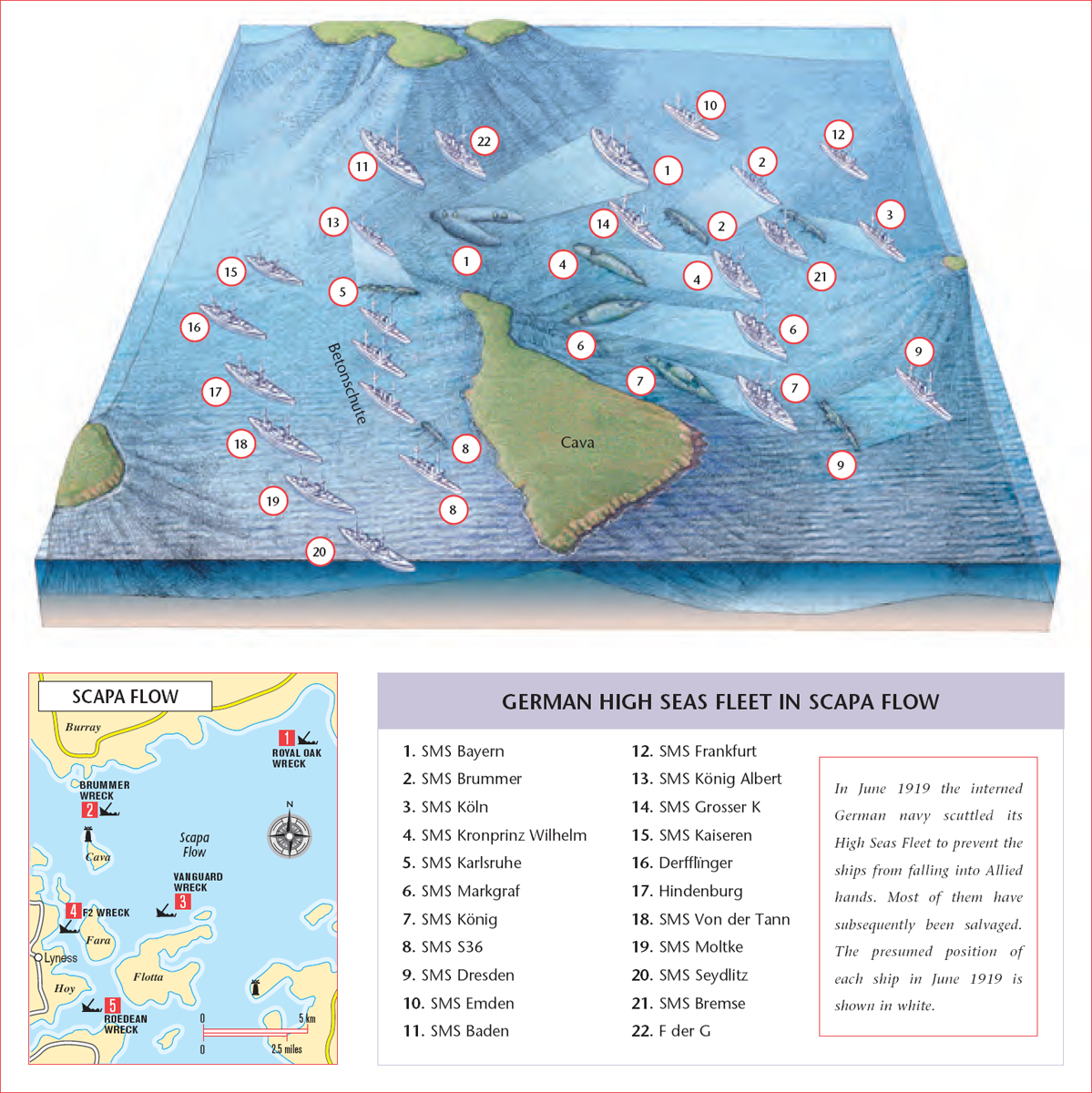

ORKNEY ISLANDS - SCAPA FLOW

I am not the first to think the Orkney Islands are magical. Witness the standing stones and stone rings dotted all over the islands. Scapa Flow is the largest sheltered natural harbour in Europe and this is where the Home Fleet made its Atlantic base during the last two major world conflicts.

Considered impregnable, the Bay of Scapa Flow, covering some 310 sq km (120 sq miles), is sheltered by a ring of protective islands. Situated 25km (15 miles) north of the Scottish mainland, access is by daily car ferry from Scrabster or by regular flight to Kirkwall airport from Edinburgh and Aberdeen.

A prime target for aerial or naval attack, a system of defence was installed in the form of anti aircraft gun emplacements, submarine netting, vigilant patrols and the now-famous blockships. This is also where one of the largest concentrations of shipwrecks in the world is found - the scuttled German High Seas Fleet, dating from 1919.

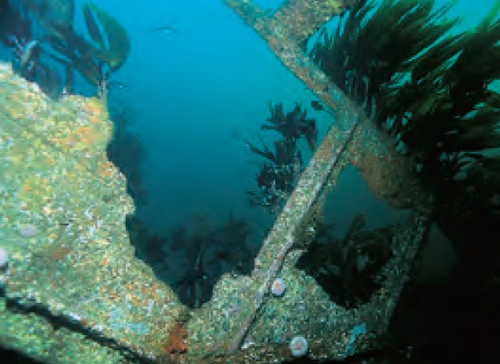

A shipwreck at Scapa Flow. Wherever the interior of a wreck is open to passing current, it quickly becomes covered in marine life.

Most diving concentrates on the sunken German fleet, but the blockships lie in clearer water at the entrance to Burra Sound. The central location of the German fleet means there is little water movement, which is fine for scuba diving, but also tends to trap particulate matter in the water column, resulting in poor visibility. This reduces the awe of these massive ships as you can only see small sections at a time and it takes many dives to explore each shipwreck safely. However, there are many other shipwrecks and remains of the already salvaged fleet, such as gun batteries, so the diving does not have to be restricted to the High Seas Fleet ships. There is also the wreckage of a WWII German ship, the F2 4, a salvage barge nearby at Lyness and older ships such as HMS Roedean 5.

Whatever your preferences, German High Seas Fleet has mystique and historical importance. The wrecks are an important part of the Orkneys’ naval heritage, having played such a significant part in its history. These ships are fortunately protected now. Their watery grave is no longer such a mystery to us, yet it is deep enough to deter those who take these ancient warhorses less seriously. The ships themselves are disintegrating at an alarming rate; bad visibility and wreckage can result in getting snagged if you are not careful; and the depth limitations are such that many divers each year succumb to decompression sickness (the bends). This results from staying too deep for too long and not taking enough time to return to the surface. The diving on the ships is perhaps some of the most advanced in Europe and only properly trained divers should attempt the German Fleet.

This deep, formidable, cold, natural harbour has served the warring nations’ fleets for centuries. At present there are remains of three German battleships, four light cruisers, five torpedo boats (destroyers), a WW2 destroyer (F2), two submarines, 27 large sections of remains and salvage equipment, 16 known British wrecks, 32 blockships and two battleships (the Vanguard 3 and the Royal Oak 1), with a further 54 sections of unidentified wreckage.

2 THE GERMAN LIGHT CRUISER

BRUMMER

The Brummer (a German light cruiser) was scuttled in 1919 at 58° 53’ 50”N, 03° 09’ 07”W. Built in the Vulcan shipyard at Stettin on the Baltic coast in 1914, she carried 360 mines and had a top speed of 34 knots. She displaced 4000 tons and was 138m (460ft) long.

The Brummer is just one of four German light cruisers that were scuttled under the orders of Admiral Ludwig von Reuter in 1919. Through the descending gloom, the graceful arch of the sharp bows comes into view. Dropping to the stony seabed divers can gaze upwards in awe at this massive ship lying on her starboard side. The hull is festooned in Plumose Anemones (Metridium senile) and feather stars (Antedon bifida). From here divers swim along the now-vertical decking, past the forward 150mm (5.9in) gun and approach the superstructure, which has mostly collapsed. The central section of the ship was blasted apart by salvage divers. The stern, however, where the other 150mm (5.9in) gun can be found, is mainly intact. Maximum depth is 36m (120ft) and divers return to surface by the mooring buoy line.

Conditions vary tremendously during the season. Visibility is generally poor and it is dark on the seabed. In the centre of Scapa Flow lights should always be used. Work-up dives should be undertaken before doing the deeper battleships. Photographers prefer the blockships at the entrance to Burra Sound, where the average depth is half that of the German warships; there is much more light; more interesting marine growth; and the water is much clearer as the tidal race at Burra Sound sweeps away all sedimentation particles. However, this also limits diving time on these wrecks and even that only at slack tide.

European wax anemones, also known as snakelocks anemones (here Anemonia sulcata) live symbiotically with spider crabs, gobies and periclimenes shrimps.

Due to strong current, visibility at the Gobernador Bories is good.

On the night of 14 October 1939, 20 years after the German Fleet was scuttled, the 188 metre (600ft) battleship Royal Oak was lying at anchor in the sheltered bay of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. Her duties were to protect Kirkwall and the British fleet from aerial attack. Scapa Flow was considered impenetrable because of the narrow passages between the reefs and islands. Attack was considered likely only from the skies. However, nobody told this to Günther Prien, commander of the U-47. He stealthily approached Scapa Flow, in what is considered by many to be one of the bravest feats in naval history and, at the dead of night, sank the Royal Oak. The Royal Oak is now a designated war grave and protected by law. Diving on her is strictly forbidden. As a result, she is the ship most divers want to visit.

TOP TEN TIPS TO DIVING AT SCAPA FLOW

Most of the diving in Scapa Flow is potentially dangerous and virtually all the German Fleet wrecks should be treated as decompression dives. Not only does this put undue stress on the diver, it considerably reduces the time to be spent in the water and the ultimate enjoyment of the wrecks. Most divers are attracted to the ‘technical’ side of deep diving. However, the larger battleships are not only in very deep water, they are all upside down, boring and, unless you want to spend your entire dive on the underside of a ship’s hull, they can be dangerous to explore any further.

Royal Navy Divers and a few civilians perform an annual memorial dive on the War Grave of HMS Royal Oak and replace the flag.

■Attend a deep diving course with a recognized training agency.

■Buy and learn how to use, not only a computer, but also standard air decompression tables - and never trust either.

■Never use your computer ‘to its limit’, always stay within the safety margin.

■Increase depth slowly for acclimatization.

■Recognize symptoms of nitrogen narcosis.

■When symptoms of narcosis appear, ascend immediately until symptoms are relieved.

■Dive only with experienced deep divers.

■Be Safe; do not put yourself or others at risk.

■Plan your dive and dive your plan accordingly, with no open-water decompression stops, use the wreck marker buoy lines for ascent and descent.

■Always obey the dive boat captain.

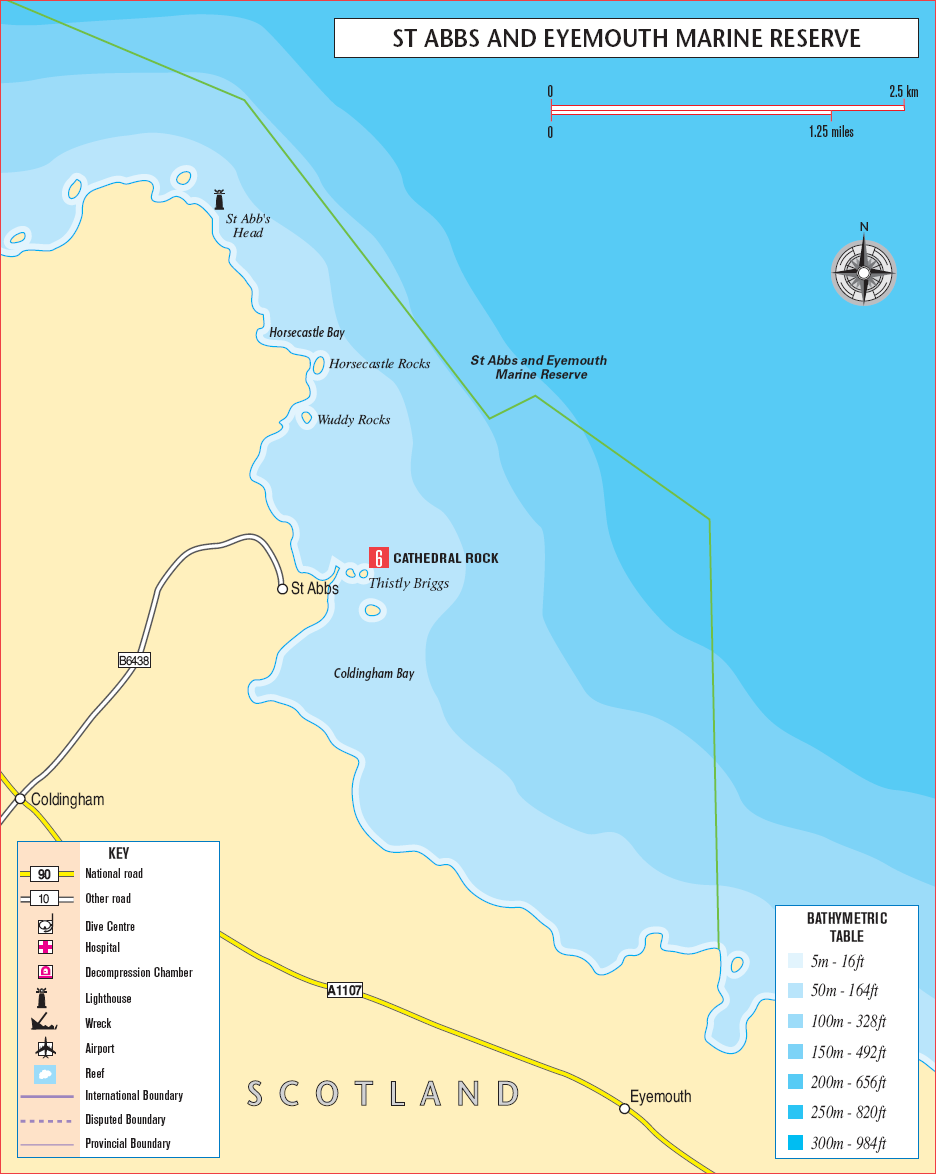

6 CATHEDRAL ROCK

ST ABBS AND EYEMOUTH MARINE RESERVE

Cathedral Rock is at Lat 550 53' 55"N and Long 020 07' 29"W. Better still, invest in Ordnance Survey Pathfinder 423 Map sheet NT 86 / 96 G.R. 922 673. Admiralty chart No.160.

At the opposite end of Scotland, on the extreme southeast coast, is Scotland’s only marine reserve, founded by Lawson Wood. First discovered in the 1950s, Cathedral Rock is the most popular dive site within the St Abbs and Eyemouth Voluntary Marine Nature Reserve and possibly one of the most dived in the whole of the British Isles.

Many divers often fail to find the site, relying on poor information, inadequate navigational skills or, more often than not, are just enjoying themselves so much off St Abbs harbour wall, that they never get as far as Cathedral Rock. The rock is part of the reef which runs perpendicular to the corner of St Abbs harbour wall, known locally as Thistly Briggs. The rock is never visible, even at the lowest of tides and many divers mistake a reef close by for Cathedral Rock. Underwater, the wall falls away and is deeply undercut with eroded horizontal strata lines, now filled with squat lobsters and Leopard Spotted Gobies. Comprising two chambers, the top tunnel is known as the Keyhole. Although it is easily negotiated, exhaust air can become trapped and kill marine life, therefore it is best not to linger in this area. The lower tunnel archway is massive, of double-decker bus proportions, with a stony bottom directly under the arch and a tumble of boulders on each side. The walls and the roof of the arches are festooned with a dwarf species of the Plumose Anemone (Metridium senile) as well as sponges, soft corals (Dead Men’s Fingers), mussels and hydroids. Small schools of pollack are often herded into this natural arena by predatory cod. For Photographers there are panoramic vistas of the archways, diver portraits, diver interaction shots and the staggering amount of macro work on nudibranchs, crabs and molluscs.

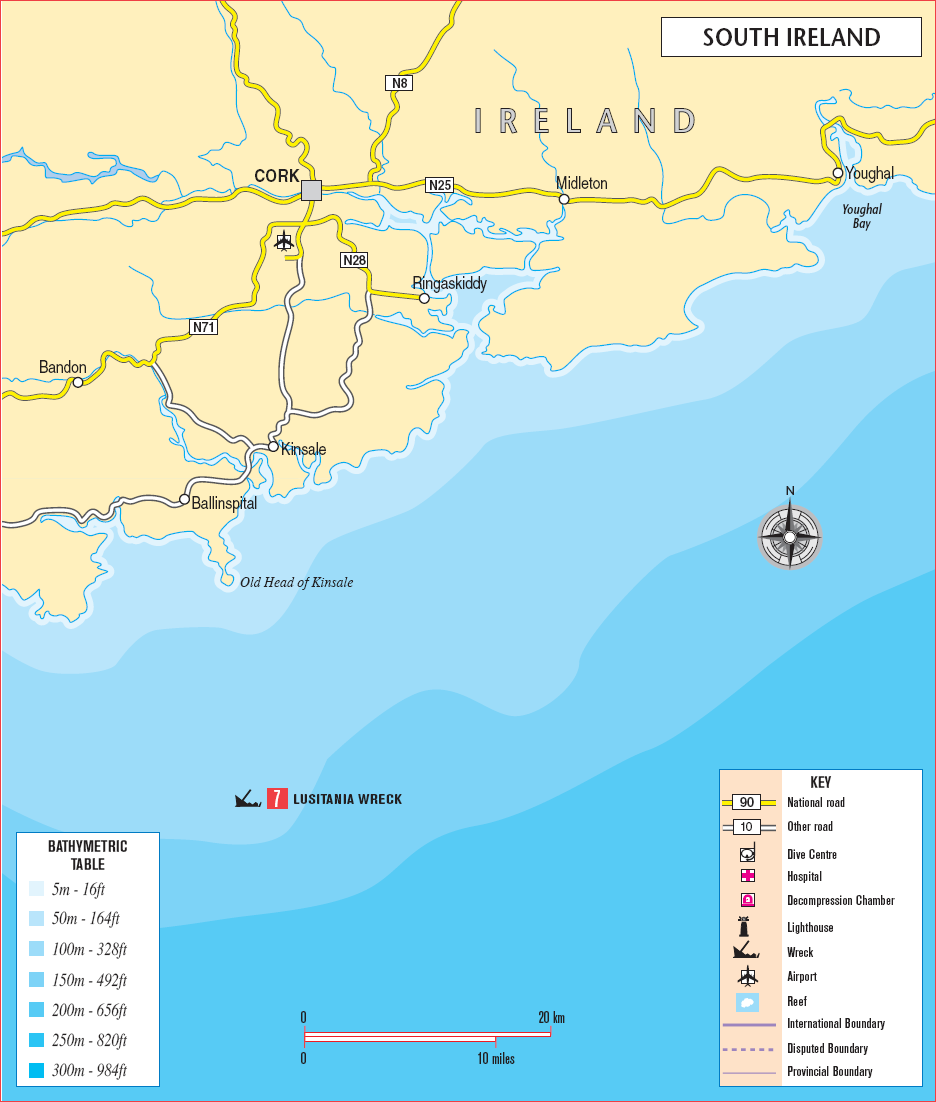

7 THE WRECK OF THE LUSITANIA

by Jack Jackson

The 232m (762ft) Cunard luxury liner RMS Lusitania was the largest and fastest vessel of her time plying the Atlantic route. She was torpedoed 19km (12 miles) south of Ireland’s Old Head of Kinsale by the German submarine U-20 at 02:10 hours on 7 May 1915 and sank in 18 minutes. More than 1200 of the 1257 passengers and 702 crew died. The fact that she was a passenger ship and that the dead included 123 Americans, 291 women and 94 children, had much to do with America entering World War I in 1917.

The wreck was first dived in 1935 by Jim Jarrett using a forerunner of the armoured one-atmosphere diving suit. The Royal Navy dived her in 1954 and in the late 1960s. In the early 1970s John Light, an American naval diver who then owned the wreck, dived her several times with limited bottom times. In 1982, using Heliox and a diving bell, her anchors and three propellers were recovered. In 1993 the locator of the Titanic, Robert Ballard, surveyed her with submersibles and Remotely Operated Vehicles.

ARGON

Technical divers using dry suits often use argon gas for suit-inflation to help maintain body temperature. Denser than air and much denser than helium, argon acts as a better insulator for retaining body heat, while inflating the suit enough to eliminate body-squeezes.

The argon is carried in a separate small cylinder, but it is particularly important to make sure that only the correct inflation hose is connected between the cylinder and the dry suit so that the gas cannot be breathed by mistake. Some divers use a standard regulator, which still has a regulator second stage attached, as well as a suit-inflation hose. The argon cylinder does not contain any oxygen, so if the diver switched to the wrong second stage by mistake, the result would be fatal.

The first visit by recreational technical divers was in 1994 when eight Britons, led by Polly Tapson, were joined by deep-wreck diving expert Gary Gentile and three of his friends from the East Coast of America. The Lusitania was dived again in 1995, 1999 and in 2001 by a Starfish Enterprise team led by Mark Jones. They worked with current owner Gregg Bemis on an archaeological survey as a precursor to raising and conserving artefacts. The wreck lies on her starboard side with the bow in good condition and draped in lost trawl nets. The stern is still recognizable as part of the ship but the middle section is badly broken up.

Ceramic floor tiles in one of the bathrooms of the RMS Lusitania.

A close-up of a porthole among the wreckage of the RMS Lusitania.

Mossel Bay is home to an offshore seal colony, which attracts Great Whites at certain times of the year for good cage diving.

African Black Footed Penguins are among many bird species on the islands off the Cape coast. These birds occasionally fall prey to a hungry Great White, but not often.