Dive Atlas Of The World: An Illustrated Reference To The Best Sites - Jack Jackson (2016)

KOMODO AND ALOR

by Michael Aw

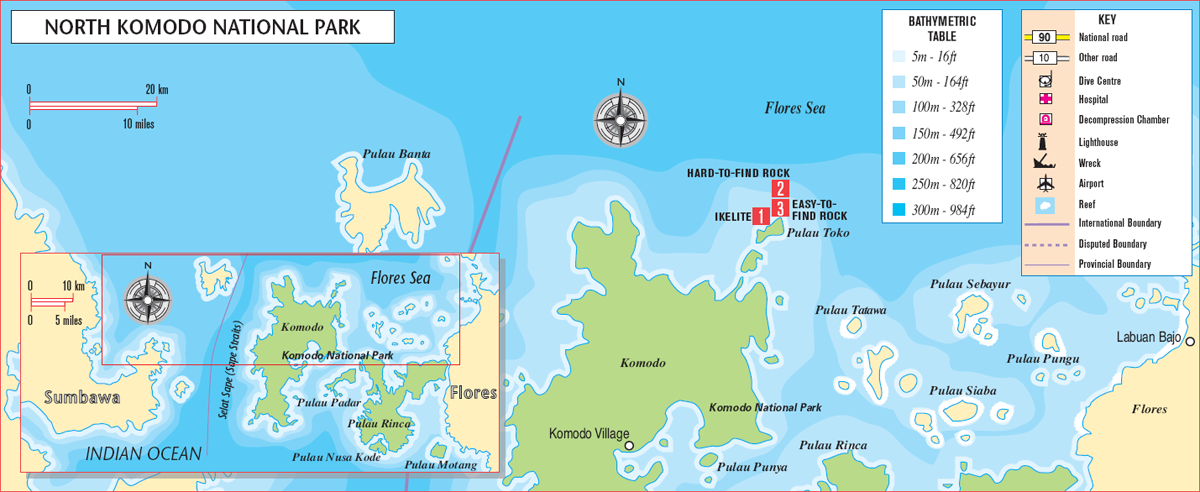

KOMODO

THERE IS SOMETHING ABOUT KOMODO THAT is rather unearthly; this group of islands with savannah landscape, resembling a wilderness that seems to belong to another place and time. Though it is only 370km (230 miles) east of Bali, between the islands of Sumbawa and Flores, Komodo is untypical of the tropical isles of the Indonesian archipelago. The arid weather conditions distinctive of the area, which has an annual rainfall of about 800mm (30in), support a dramatically desolate setting of harsh, undulating terrain punctuated at random with Lontar palms. The huge volume of water that washes back and forth between the Indian Ocean and Flores Sea amid uncountable shelters, bays, and islets makes this location perfect for the intrepid diver.

The islands are the habitat of the Varanus komodoensis, a giant, primeval monitor lizard that walks and grunts aggressively like a dinosaur. The Komodo Dragon is the largest lizard in the world and when a Dutch aviator reported his sightings in the early 1900s of 4m (13ft) dragons roaming in Jurassic-like countryside, his story was probably considered the product of a silly explorer’s imagination. It wasn’t until another Dutch-man, this time a military officer, Van Steyne, brought two cadavers to the Bogor Zoological Gardens in 1912, that the curator, PO Ouwens, formally described the animal as Varanus komodoensis. Today there may be as few as 3000 of these prehistoric monitor lizards remaining in the wild. Because they exist nowhere else, scientists began to lobby for their protection as far back as 1915. In 1977 the Komodo Island and environs were listed in the UNESCO Man and Biosphere (MAB). This is a worldwide programme designed to conserve the remaining diversity of plants, animals and microorganisms that make up our living biosphere.

Encouraged by the listing, the local municipality inaugurated Komodo National Park in 1980 to protect the area’s biological diversity, particularly the habitat of the last of the dragons. In all, the park has a total land area of 75,000ha (185,325 acres) and encompasses a number of environs including islets, bays, mangrove swamps and islands. The largest island is Komodo with 34,000ha (84,014 acres), followed by Rinca with 20,000 ha (49,420 acres), Padar, Nusa Kode, Motang, numerous smaller islands, and the Wae Wuul sanctuary on Flores. A total of 112,500ha (277,988 acres) of the surrounding waters is also under the jurisdiction of the park rangers. The landscape stirs the imagination with its exotic hillsides covered by dry savannah and pockets of thorny green vegetation contrasting starkly with the brilliant white sandy beaches and blue waters surging over coral reefs.

Extensive research suggests that reefs around here are among the most productive in the world due to upwelling and a high degree of oxygenation from strong tidal currents that flow through the Sape Straits. Beneath Komodo lie some of the last pristine coral reefs, which by themselves are the richest on the planet.

Marine naturalists have compared diving these waters to being in the middle of the wildebeest migration in the Serengeti. The marine biodiversity encompasses an unimaginable variety of invertebrates, over 1000 species of fish and 250 species of reef-building corals with new ones constantly being discovered. In 1991, Komodo National Park was inscribed on the World Heritage List.

Though Komodo is renowned for swift currents and pelagic fish life that can leave one in awe, there are many sheltered bays, submerged reefs and calm reef slopes endowed with pristine coral coverage, rare critters and zillions of ornamental reef fishes. One such dive is in a sheltered bay called Big Fat Rock where hundreds of batfish are predictably found. Schools of barracuda are also found hanging out on the ocean side of the rock and groups of Spotted Sweetlips in large numbers are found at 30m (100ft). Corals and sponges cling to every square inch, others thrive in symbiotic or parasitic relationships. Swarming on every ledge and crevice are hundreds of angelfish and butterflyfish. Damsels frolic in an Acropora coral at 10m (33ft). It is one of those splendid sites that one can return to again and again. But be warned: some sites are not for the faint-hearted. They have rapid currents, up and down, in eddies, and six-knot drifts are not uncommon. Diving in such conditions demand a higher level of alertness and preparation.

One of the inconveniences of diving Komodo is that the water temperature varies from 30°C (86°F) in the north to a chilly 19°C (66°F) in South Komodo. Expect 25-30m (80-100ft) visibility when diving the north, but moving south the azure water gradually surrenders to the nutrient-rich water of the Antarctic Ocean. Frequent upwellings make the water colder, and green, so that visibility sometimes drops to a mere 5m (16ft). But it is all worth it; the rich cold water yields an assemblage of critters that become the signature of Komodo diving. One such place is Cannibal Rock, another rock that falls steeply to 25m (80ft). Gorgonian Sea Fans, organ pipe corals, black coral trees, orange sponges and carpets of red, blue, green and yellow feather stars festoon the slope and hundreds of tapestries of ornamental reef fish swarm in the water column. At 20m (66ft) the rock is surrounded by a garden of sponges and tall coral trees; snow white coral trees adorned with Long-nose Hawkfish. Sea Apples and a bright red sedentary cucumber are found in abundance on the reef slope. While orange, blue, yellow and white frogfish and Ghost Pipefish merge with the rich foliage, multicoloured nudibranchs, feather stars, tunicates, soft corals, anemones and sponges are common. Though some dive sites in North Komodo are accessible by day trip from Labuan Bajo on the island of Flores, the best way to explore Komodo is by one of the diving-dedicated live-aboard vessels operating from Bali.

1 IKELITE REEF

Located near the edge of Pulau Toko, Ikelite Reef is a rock that rises like a mountain from 50m (165ft) to near-surface. Fish life and coral life here is spellbinding, with schools of resident barracuda, sweetlips and jacks. To fish ecologists, this site is a well-known grouper aggregation and breeding spot. By nature’s biological clock, groupers come here from miles around to ‘stir the pudding’ and make baby groupers. Possibly they congregate here to procreate because two merging currents create a ‘washing machine on rinse cycle’ effect that most efficiently disperses their sperm and eggs. Most of the time, a manta or two can be seen gliding here, as well as some rare scorpionfish, including beautiful yellow Leaf Scorpionfish. Dolphins usually hang out just out of visibility range, which is often a respectable 25m (80ft), and beyond.

Immune to the stinging cells of the anemone, this tiny clownfish will probably live out its life within this anemone.

Sea Apples, bright red sedentary sea cucumbers found only in colder tropical waters, are abundant in South Komodo. A relative of the sea star, this attractive species of sea cucumber feeds by trapping food in the passing current with its waving tentacles.

Longnose Hawkfish (Oxycirrhites typus) can be found among the black coral trees of Komodo at depths of 15m (50ft) to 30m (100ft).

HARD-TO-FIND ROCK 2 AND EASY-TO-FIND ROCK 3

Hard-to-Find Rock (HTF) and Easy-to-Find Rock (ETF) are close to Pulau Toko. They offer similar marine life and bottom contours. Only one rock is exposed, making it easy to find and the other is submerged, even at low tide, making it hard to find. It was at HTF rock that pygmy sea horses were first discovered in Indonesia. And, yes, they are still there. Also, there are some brilliant pink/purplish Leaf Scorpionfish on HTF Rock. Most of the time, there are resident schools of big spadefish hanging around both sites. A good-sized school of barracuda usually hangs out around 30m (98ft) on the west side of ETF Rock. Typical of submerged reef in North Komodo, the reef’s edge falls from about 5m (16ft) to 45m (148ft). It is entirely overgrown by encrusting sponges, tunicates, sea whips, and coral colonies. This is also a spawning site for Napoleon Wrasse, Blotched Fantail Rays and sweetlips. On the seaward side, Whale Sharks and mantas are frequently sighted.

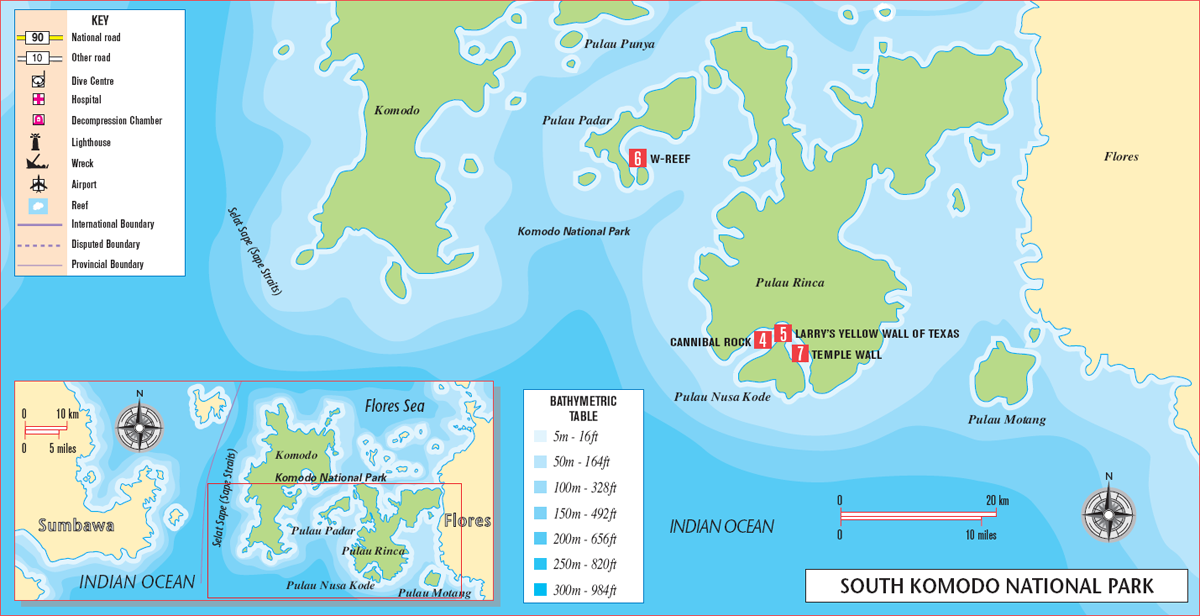

4 CANNIBAL ROCK

Located off Rinca Island, one of Komodo National Park’s most spectacular landscapes, Cannibal Rock has been described by well-travelled divers as one of the top five dive sites in the world. There are meadows of multicoloured feather stars that harbour frogfish, cuttlefish, snails and many rare nudibranchs. Cannibal Rock has an abundance of little gems of the sea from 5m (16ft) to beyond 35m (115ft). There are Ghost Pipefish, fire urchins complete with Coleman Shrimps, zebra crabs, yellow, white, and pink pygmy sea horses (Hippocampus bargabanti), mobula rays, Manta Rays and oversized Spanish Dancers.

Cannibal Rock, South Komodo, falls steeply to 25m (80m), decorated with Gorgonian Sea Fans, corals, sponges, carpets of feather stars and swarms of ornamental reef fishes.

5 LARRY’S YELLOW WALL OF TEXAS

Situated on the south side of Rinca, this site is called the Yellow Wall of Texas because of the rich foliage of yellow soft corals, yellow encrusting sponges, and yellow frogfish. It seems like just about everything here has some yellow somewhere on it, making it a truly beautiful site. The wall is nearly vertical and falls straight to over 50m (165ft). At around 35m (115ft) the wall curves into a spectacular overhang, covered from floor to wall with lush invertebrate and fish life.

The shallow slope of this site is dotted with big barrel sponges and they are home to the little fuzzy and purple Sangian crab with blood-red eyes. The Yellow Wall of Texas goes on and on, sometimes punctuated for a short distance by areas of coral slope. Currents are not much of a problem here. Spanish Dancers are almost always found, but mostly during night dives. Because it is in the strait between Rinca and Nusa Kode, The Yellow Wall of Texas is always protected from any weather from any direction.

Criniods and crinoid critters, frogfish, emperor shrimp, whip coral shrimp, sleeping sharks, orangutan crabs and jacks are easily found. The display of colours is a delight for professional photographers. Though subject to swell and tidal currents, Yellow Wall of Texas is easily accessible at any time of year.

6 W-REEF

W-Reef consists of a series of pinnacles located near Padar Island. The shallowest reef starts at about 4m (13ft) from the surface and the deepest at around 25m (80ft). It derives its name from a series of rocks that form a big underwater W. Giant Dogtooth Tuna, mobula and Manta Rays are frequently seen here. Nudibranchs are found in large numbers, frogfish abound and the sea fans are home to pygmy sea horses. A small cave next to the sea horses is reputed to have the biggest congregation of moray eels on the planet resting alongside Nurse Sharks. W-Reef is known to have something for everybody - from strange, minute critters to big pelagics lurking in the depths off the wall. The site is notorious for strong currents, thus the best time to dive here is when the moon is around half full. At full or new moon (at spring and neap tides) the currents are difficult to manage.

7 TEMPLE WALL

The long swim-through at a depth of 30m (100ft) at The Temple Wall off Rinca passes through an interesting rock formation. The wall is completely covered with colourful soft corals and splashed with multicoloured crinoids. A resident school of sweetlips hangs out in the dramatic structure of basalt rock platforms creating the feeling that one is diving in a temple. The wall is a kaleidoscope of orange cup corals and purple, pink, red and yellow ascidians. The site is subject to strong swells.

Current beneath The Dream is so strong that even big fish seem daunted. The unpredictability of the currents further taxes divers’ skills to the limit.

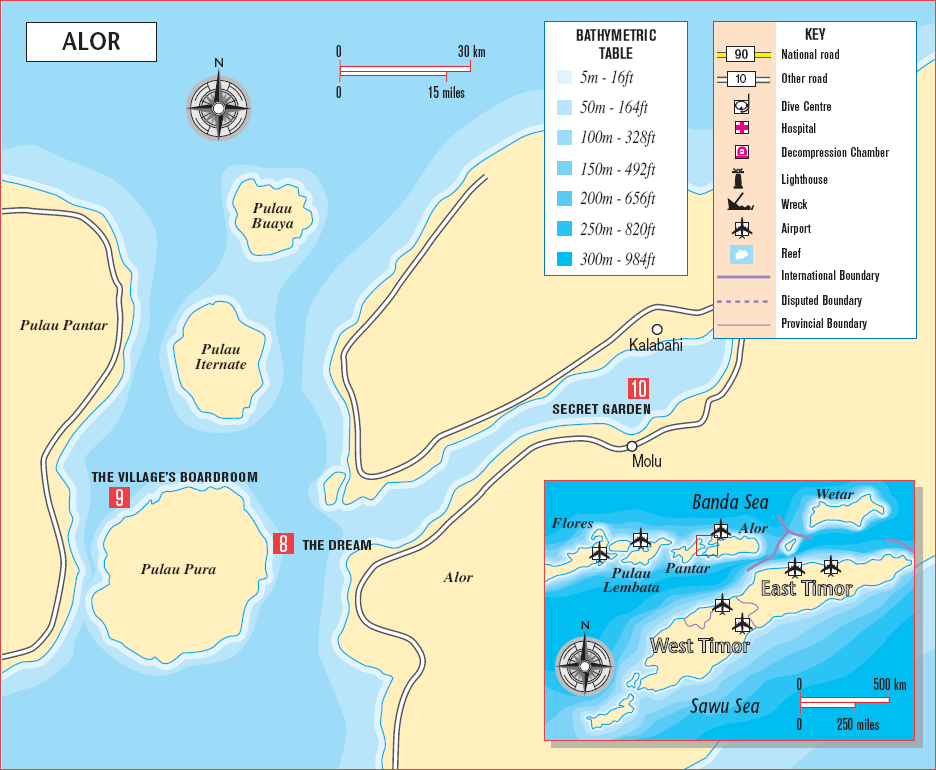

ALOR

The Alor group of islands, lying less than 50km (30 miles) north of central Timor, is one of Indonesia’s least explored areas. The arid, rugged, mountainous terrain makes travel in its interior difficult. This natural barrier has isolated the island’s many tribes and ethnic groups, not only from the outside world, but even from neighbouring communities. The population of only 100,000 is split into more than 50 separate tribal communities, each with its own language.

Luckily the island’s coastline is more accessible, with motorized vessels bypassing the difficulties of overland travel. The coastline offers sparkling beaches and huge swathes of reef waiting to be discovered. Tidal forces push vast quantities of water back and forth through the narrow straight between Alor and its neighbouring island, Painter, to the west. Jagged coastlines and tiny islets, which dot the channel, make navigation perilous. The ever-changing and unpredictable currents also make diving here rather demanding. The deep, cold, nutrient-rich waters running beneath the Sawu Sea collide with tropical waters from the Banda Sea, resulting in thermoclines and plankton blooms which sometimes limit underwater visibility. However, these same conditions also provide a haven for marine life, which is the richest and healthiest in the Indonesian archipelago.

There are three distinct terrain types for exploration: the submerged sea ridges, outer fringing reefs, slopes and walls, and the brackish bay-water environment. While a respectable number of robust Grey Reef Sharks are often found patrolling deep reefs, schools of Dogtooth Tuna and Rainbow Runners, massive curtains of Golden Trevallies, Spanish Mackerel, and surgeonfish swarm the submerged and fringing reefs. Parades of Bumphead Parrotfish gnaw corals and encrusting algae, while vast numbers of smaller ornamental reef fish flutter in the currents, all but obscuring the corals on the reef’s walls and plateaus. Often, it is necessary to swim through schools of barracuda just to see the sharks. Big pelagics, magnificent walls covered with lush soft coral, Gorgonian Sea Fans in a variety of colours, and friendly octopuses can be seen on almost every dive. Three dive sites are benchmarks of diving adventures in Indonesia - Secret Garden, the Dream, and the Village’s Boardroom are located around three islands lying between Alor and Pantar: Pulau Buaya, Ternate and Pura.

8 THE DREAM

The Dream is not for the neophyte diver or the faint-hearted. The submerged reef systems in the channel between Pura and Alor are like obstacles in a pinball machine as huge volumes of water flow through the gaps and currents of up to six knots are generated in unpredictable directions. Even the big fish seem daunted by the current. On two occasions we were careened to The Abyss, a sheer wall, by downcurrent. We briefly converged with tuna, dolphin fish, sharks and trevally, and realized we were about to be sucked out to the blue by another current. We climbed, hand over hand, from 60m towards shallower water, while fellow divers were being plucked off the wall one after the other by the surges of passing current.

Diving pioneer Karl Muller rated this, say local dive operators, among the top five dives of his long and varied career. Sharks (including abundant Grey Reefs), Dogtooth Tuna, Yellowtail and Great Barracuda appear in phenomenal numbers, and in sizes ranging from good-sized juveniles to the biggest adults. They come in close to check out divers, perhaps encouraged by the dense swarms of schooling fish on the reef - snappers, Blue Triggerfish, unicornfish, surgeonfish and fusiliers - sometimes there seems to be more fish than water.

Napoleon Wrasse, rays and the mother (or father) of all Giant Groupers, at least 2m (6ft) long and as bulky as a small car, are also often seen here. The reef is densely covered with sponges, barnacles and corals - particularly Tubastrea corals. However, the strength of the constant current forces coral to grow tight in against the reef. Coral growths at the reef-face don’t stand out more than 20cm (8in), but at this site the stunted growth continues down the slope for at least as far as the edge of visibility at 70m (230ft). By virtue of the reef profile, this site is only for experienced divers.

9 THE VILLAGE’S BOARDROOM

Situated on the northwest coast of Pura, a steep wall falls to a depth of beyond 70m (230ft). The wall is punctuated with caves and overhangs, with a concentration of shallow caves in the 10-18m (33-60ft) range containing some spectacular virgin coral growth. The boulder slope closest to the coast on the inner side of the wall is entirely overgrown with coral, and there are large barrel sponges all over the site. The corals are predominantly soft species, particularly in the caves and overhangs. The reef fish population is rich and diverse; all the normal small species are well represented, but the larger schooling species are the most profuse, with dense schools of fusiliers, surgeonfish, jacks and Black Snappers all commonly found. Big sweetlips are also around in noticeable concentrations and sharks, including Whitetip Reef, are widespread.

However, the attraction of the Boardroom is really the people who live in the bay. Each day, when the spirit moves them, the village people convene in this small bay; adults and children alike play, swim and free-dive among the coral reefs that have sustained these families for generations. They have a childlike innocence, which they share easily with visiting divers. It is not uncommon to find a few of them free-diving to pose for underwater photographers in full scuba equipment.

10 SECRET GARDEN

Three coconut palms hang over this site on the dark stretch of water of Kalabahi Bay on the island of Alor. From about 15m (50ft) below the surface to a depth of below 30m (100ft) the area is covered by a forest of gold, white, green and black coral trees, barrel sponges, red soft coral trees, staghorn corals and encrusting sessile animals. While tidal currents bring in huge amounts of plankton-rich water to sustain the enormous density of filter feeders, larvae take up residence on this already overcrowded suburb, settling for ‘apartment-dwelling in an urban high-rise society’.

Flame files shells are found only in the inner recesses of caverns, cracks and dark places. The red membrane seems to shimmer rhythmically when illuminated by divers’ lights.

Beneath the fronds of the three palm trees, the strangest and the oddest critters, rare in other coral reefs of the world, are common. Associates of both large and small animals occupy every space conceivable - anemones hosting clownfish, porcelain crabs and transparent shrimps, feather stars with fascinating residents of clingfish, shrimps and squat lobsters, allied cowries on every branch of gorgonian coral, and territorial gobies on whip coral. Reportedly, David Doubilet, the world’s most celebrated National Geographic underwater photographer, once visited Alor and dived this reef twice a day for ten days.

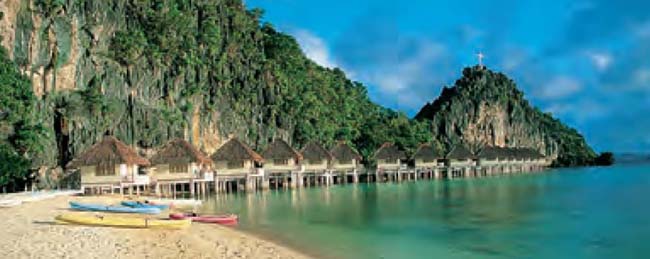

The main beach and wooden chalets at Club Noah Isabelle. It is the only habitation on Apulit Island in Palawan’s Taytay Bay, where fishing is now banned and large fish are common.

Outrigger boats called bancas across Alona Beach - typical of the larger ones used on diving safaris to various destinations.