Caribbean: The Lesser Antilles - Insight Guides (2016)

ISLANDS IN THE SUN

The rich diversity of these tropical islands is plain to see - from their mountain rainforests to the ocean deep.

The islands of the Lesser Antilles form a delicate necklace of coral, basalt, and limestone stretching from the Virgin Islands in the north through a 1,500-mile (2,400km) arc to the Dutch islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao off the coast of Venezuela in the south.

The wild Atlantic coastline of Barbados.

Getty Images

Each small landmass is often within sight of another. So when Amerindians, the earliest people to colonize the Eastern Caribbean, started to move north from South America, they could stand at the northern tip of one island and see - if only as a blurry mauve outline across a truculent channel - the southern tip of the next island. It was an encouragement, perhaps, to move on, to see what new creatures, plants, landscapes, opportunities lay on the horizon.

The wild Atlantic side of most Eastern Caribbean islands has more in common with a Scottish seascape than the gentle white-sand beaches of the hotter and drier Caribbean coast usually only a few miles away.

Each island to its own

The Eastern Caribbean islands are physically (and culturally) places of great variety. The images of sparkling white sand, clear turquoise sea, and shimmering coconut palms of the travel advertisements do the region a disservice. It is a far richer region than that, with each island’s topography reflecting its story.

French West Indies, Guadaloupe.

Getty Images

From the pristine rainforests of Dominica and St Lucia, where rain pounds the mountaintops with up to 300ins (760cm) of water annually, and tree ferns shimmer in a silver light, to the dry, brittle scrublands of acacia and logwood of St-Martin or Barbuda, there seems to be a vegetation for every mood. Even if you stay on only one island, there is often a remarkable range of ecology to be explored: from rainforest canopy to coastal swamp and coral reef.

The flatter islands are less varied and, in many cases, they have been more vulnerable to exploitation. Thus Antigua and Barbados lost their original forest covering to sugar-cane plantations, leaving a landscape largely of “bush,” with residual areas given over to the cultivation of sugar and vegetables, or the rearing of livestock.

The ocean and the deep blue sea

Yet wherever you arrive in the Caribbean you are greeted by a sweetness of smell and the breezes of the cooling trade winds. Its tropical climate delivers relatively constant hours of sunshine, and a temperature hovering around 86°F (30°C) in the Eastern Caribbean.

The trade winds, which guided the first Europeans to the Caribbean at the end of the 15th century, blow in from the northeast, first over the typically wilder coasts of the wetter windward sides, which are buffeted by the tempestuous Atlantic Ocean, and then across in a more gentle fashion to the tranquil, leeward Caribbean Sea.

Alive and kicking

With the exception of Barbados, which is perched out on its own, much of the island chain (from Saba to Grenada) was created by volcanic action when the two tectonic plates which sit beneath the “necklace” shifted. The eastward-moving American plate pushed under the westward-moving Caribbean plate and threw up what became this pattern of islands. However, Barbados, to the southeast, was formed by a wedge of sediments pushed up slowly; it is encrusted with the remnants of ancient coral reefs which developed as the water became shallower over the sediments. To the south, Trinidad and Tobago were joined to Venezuela during the ice age when the sea levels were much lower, accounting for the similar fauna and flora on the islands.

Some islands are much older than others: those that have been worn down by erosion, subsided below sea level and then raised up again are the flatter, drier islands of Anguilla, St-Martin, Barbuda, and Antigua, on the outside of the volcanic rim.

Rip-roaring hurricanes

A hurricane blows up when the atmosphere’s pressure plunges far lower than that of the surrounding air. Usually spawned in the Atlantic, continuous winds of up to 150mph (240kph) blow around the eye, a calm central zone of several miles across, where the sky is often blue.

Hurricanes can reach up to 500 miles (800km) in width and travel at 10-30mph (16-48kph), speeding up across land before losing force and dying out. They leave in their wake massive destruction of towns, homes, and crops, but islanders are warned of approaching storms and official hurricane shelters are allocated (see Travel Tips).

Lists of hurricane names are drawn up 6 years in advance in alphabetical order by the National Hurricane Center in Miami. The tradition started during World War II when US servicemen named the storms after their girlfriends. In 1979, concern for equal rights led to the inclusion the use of male names.

Most hurricanes occur between June and November, and the average lifespan of a hurricane is 8 to 10 days.

Memorable hurricanes over the past few decades have been David (1979), which devastated Dominica; Hugo (1989), which flattened Montserrat; Luis (1995), which roared through the Leewards with Marilyn hot on his tail; Lenny (1999), which affected St Kitts; Lili (2002) and Ivan (2004), which hit Grenada and St Vincent; Tomas (2010) which brought flooding and mudslides in St Lucia; Irene (2011) which passed over the Leewards, causing widespread destruction and at least 56 deaths across the Caribbean, US and Canada; and Erika (2015) which caused at least 31 deaths, and intensive flooding and landslides in Dominica.

The ruins of an old sugar mill.

Getty Images

The geologically younger islands are physically more dramatic, with mountain ranges and steep-sided valleys. Some, such as Montserrat, Guadeloupe, St Vincent, and Martinique, have experienced volcanic activity in the 20th century - from the devastation of the town of St-Pierre in Martinique in 1902, when some 30,000 people were wiped out, to the most recent activity, which began in 1995 in the Soufrière Hills in the south of Montserrat. This crisis resulted in the “closure” of two-thirds of the island, and the evacuation of much of the population.

Soufrière (from the French word for sulfur) is the name given to volcanoes in the region and several neighboring villages. In St Lucia, for example, the “drive-in” volcano, with its moonscape of bubbling mud, mineral pools of boiling water, and sulfur springs, is near the southern village of Soufrière.

The aftermath of Hurricane Gonzalo, St Martin, 2014.

PA Images

This dramatic landscape continues underwater where there are mountains, including a submarine volcano just north of Grenada called Kick ’Em Jenny, hot springs, caves, lava flows, overhangs, pinnacles, walls, reefs, and forests of elkhorn coral.

Volcanoes apart, the threat from hurricanes is a constant feature of life in most of the Eastern Caribbean, with really only Trinidad and Tobago and the ABC islands lying safely outside the hurricane belt. The hurricane season (June too soon, July stand by, August it must, September remember, October all over) interrupts the rainy season, from May to Christmas, often to devastating effect, endangering lives and destroying homes, businesses, and crops. The traditional dry season is from around Christmas to May, when water may be in short supply. It is then that the flowering trees and shrubs, like the red-bracted poinsettia, put on their most festive display.

Trinidad is the only island that is home to four species of venomous snake - the bushmaster, two types of coral snake, and the fer de lance.

Tropical wildlife

While the flora of the Lesser Antilles is of international importance, the region is less well-endowed with fauna. Many animals, such as the agouti, opossum, and the green monkey (found in Barbados, Grenada, and St Kitts and Nevis) were introduced by man. The mongoose, a creature that resembles a large weasel, was brought over to control rats and snakes, but as rats are nocturnal and mongooses aren’t, they succeeded in becoming pests too, plundering birds’ nests and rummaging through garbage.

The islands in the middle of the necklace received fewer migrants of both bird and animal life. However, the relative isolation of some of them allowed for the evolution of endemic species: Dominica and Montserrat are the home of a large frog known as a mountain chicken, that is found nowhere else in the world. Lizards and geckos are everywhere but the poisonous fer de lance snake lives only on St Lucia, Martinique, and Trinidad. Red-bellied racer snakes are found only on Saba and Sint Eustatius; St Lucia has the only whiptail lizard in the Eastern Caribbean, living on its offshore islets; remnant populations of the endangered Lesser Antillean iguana, hunted for their meat, survive on six islands including Saba and Statia. Night-time can be a noisy affair on any island as frogs of all sizes tune up, with some of the loudest often being the tiniest.

The Windward Islands each have their own indigenous parrot, which have become endangered through loss of habitat caused by hurricanes and farmers, and there are other indigenous birds on many islands. While you may not always see a parrot, every day will bring a hummingbird winging its way in a million flutters “to a hibiscus near you.” Indeed, birds are a constant presence, although you will have to go to Trinidad and Tobago (for their 469 species) for the most exotic.

Seabirds and other waterbirds should not be overlooked either, as their existence is closely linked to the islands. From the herons and egrets stalking through swamps and wetlands, to the magnificent frigate bird that cannot walk on land but soars for days in the sky, to the awkward brown pelican perched on a jetty or the graceful red-billed tropic bird skimming the water in search of squid or flying fish (which the frigate bird may force it to disgorge later), there is a wide range of birds to look out for.

Sulfur springs on St Lucia.

iStock

A money spinner

Although these small islands are largely rural in character, clinging to fishing and farming traditions and celebrating festivals linked to these activities, in the last decades of the 20th century their economies began to shift away from agriculture to tourism. It is now the region’s greatest money spinner, bringing employment and dollars. Like the first colonizers, who dramatically altered the island hinterlands by clearing the forests - first for tobacco, then coffee and cocoa, and then for sugar - the tourist industry has changed the coastlines forever. The bays where fishermen once pulled in their nets, or where colonies of birds nested in mangrove stands, now provide for the very different needs of tourists.

The fragile environments of these small islands are, in some cases, in danger of sinking under the weight of visitors. Local and international environmental groups are vocal in contesting the destruction of important mangrove stands for hotel building; the destruction of habitats and wildlife corridors when roads and buildings appear; the damage done to coral reefs by careless tourists and the anchors of cruise ships; plus the cultural threat imposed on small societies by the hordes of holiday-makers, apparently with limitless funds.

“Sustainable” tourism is now the buzzword, and some islands, such as Dominica and Trinidad, which have not developed a “sand, sea, and sun” tourism have declared policies for developing along those lines, with the involvement of the communities affected. Visitors, too, are discovering that there is more to the land- and seascapes of the Caribbean than the limited view from a sunlounger; between them, environmentalists, policy-makers, and visitors may ensure that the diversity of that island necklace will survive.

Ecosystems of the Lesser Antilles

Although most of the primary rainforest has been destroyed there is a huge variety of ecosystems on the islands.

The archetypal image of a Caribbean island is one of volcanic mountains clad in forest growing right down to the seashore, the Pitons of St Lucia being a prime example. There is, however, a huge variety of ecosystems on the islands, despite their small size. An island such as St Lucia or Martinique may contain rainforest, cloud forest, elfin forest, dry tropical forest, thorn scrub, coastal wetlands, swamps, and mangroves. Even the Pitons have several different vegetation zones, depending on altitude.

Little primary rainforest can be found on the islands as it has been cleared by man or destroyed by hurricanes or lava flows. However, many islands have good secondary rainforest, much of it protected, and an invaluable water catchment resource. What is often referred to as rainforest is in fact montane forest, found on the middle slopes of the mountains of the Caribbean. Trees here reach a height of 32-40ft (10-12 meters) and are covered with mosses, lichens, and epiphytes (sometimes known as air plants; they live on other plants but use them only for support, and are not parisitic). Elfin woodland is found on the highest peaks, such as on Saba’s Mount Scenery, almost permanently in cloud with low temperatures and lots of wind. Trees here are dwarf versions of what grows on lower slopes, more spreading in habit and contorted by the wind. They are often covered with epiphytes, mosses, and lichens, which thrive in the moist atmosphere and high rainfall.

Areas with a more moderate rainfall have a semi-evergreen forest, where many trees shed their leaves in the dry season and burst into flower, so that their seeds are ready for the next rainy season. Dry woodland areas are less rich in species, the trees are shorter, and there are fewer lianas and epiphytes. Most trees shed their leaves in the dry season and their bark is thick, helping them to retain moisture.

Drier still are the areas of thorn scrub, usually found near the coasts, where the ground might have been cleared at some stage, followed by the grazing of goats, sheep, and cattle. The tallest plants here are usually no more than 12ft (3 meters) and they have adapted to dry conditions by growing very small leaves, or no leaves at all in the case of cactus, and the most successful have thorns or spines to ward off grazing animals. Closer to the beach are sea grape, manchineel, and coconut, which can tolerate a higher salt content in the soil.

Protecting the mangroves

Mangroves grow on the coast in shallow bays, lagoons, estuaries, and deltas where the soil is permanently waterlogged and the mud is disturbed daily by the tides. There are many different types of mangroves, but they are an important breeding ground for fish, and home to crabs, molluscs, and many birds.

In Barbuda an enormous colony of frigate birds, who are unable to walk on land, and a number of other birds have taken over a huge area of mangroves in Codrington Lagoon, while in Trinidad, the Caroni swamp is the night-time roosting place of the scarlet ibis and egrets, and both areas have become major tourist attractions. Mangroves can be cut back to make charcoal and they will regenerate within a few years, but if they are cleared completely for a marina or resort hotel, valuable nurseries are lost forever.

A scarlet ibis can’t help but catch the eye.

Shutterstock

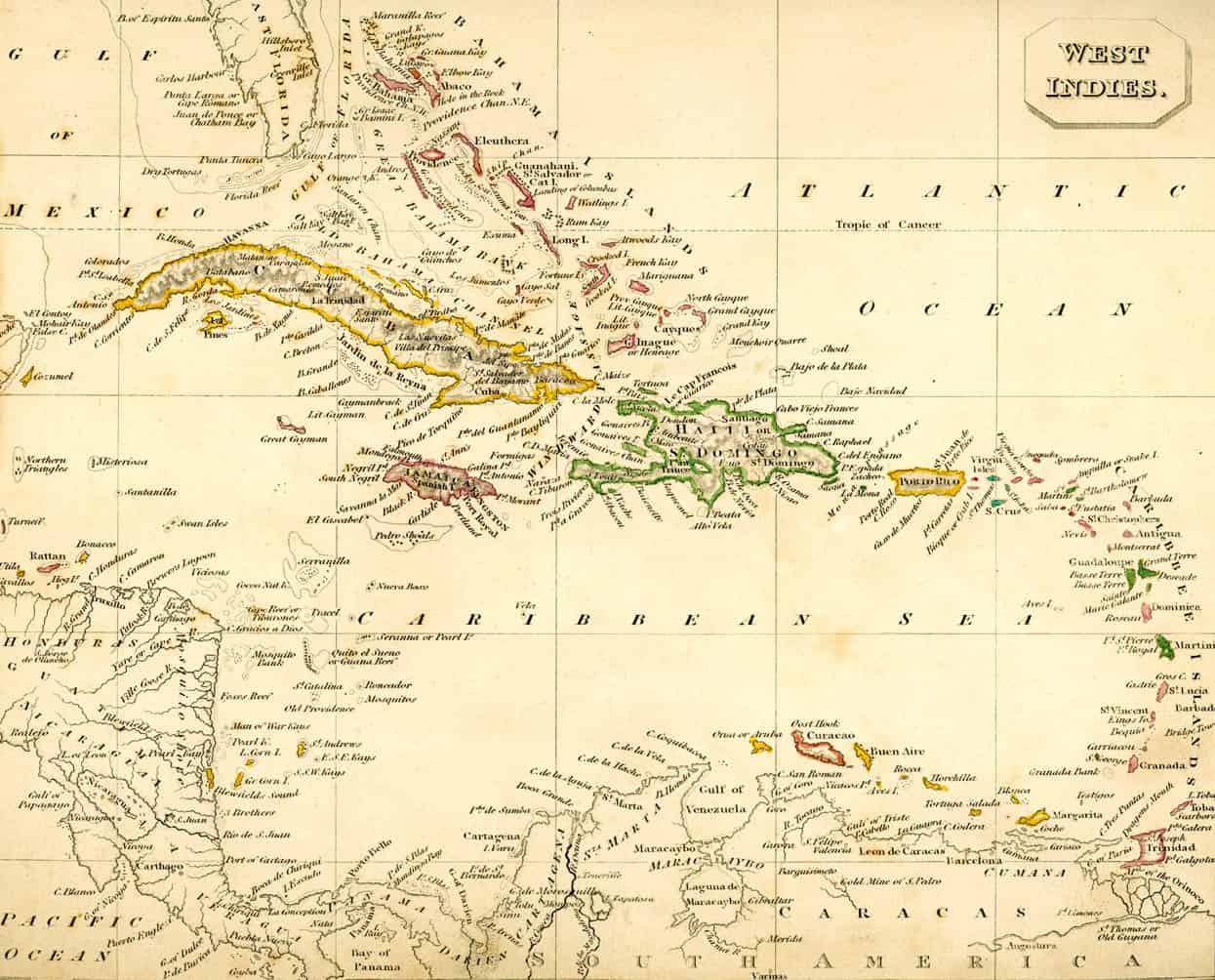

Antique map of the West Indies.