Caribbean: The Lesser Antilles - Insight Guides (2016)

AND THE BEAT GOES ON

Caribbean music never stands still and the eastern islands, where fusion is a way of life, are among the most exciting musical regions in the world.

Think of Caribbean music, and what do you come up with? Reggae would be an obvious first choice. Almost everybody can recognize the sound that took the world by storm in the 1970s with artists like Bob Marley and Peter Tosh and which is still a force to be reckoned with. And then what? Salsa became a phenomenon in the 1980s, with Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and mainland Latin Americans setting the pace. Then there’s calypso and steel pan, the infectious good-time music that seems to evoke the region in its every note.

Rihanna performs at Nikon at Jones Beach Theater, New York.

Getty Images

The award-winning Bajan sensation that is Rihanna exploded on the music scene in 2005, when she was just 17. Now one of the best-selling artists of all time, she tours worldwide with her mix of R&B, pop, reggae, and dance.

But these four totally different types of music are just the tip of an ever-growing musical iceberg. Leaving aside the bigger islands, such as Jamaica, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, even the smaller territories of the Lesser Antilles reveal an extraordinary diversity of styles and sounds that run from A to Z. In between Trinidad’s aguinaldo and Martinique’s zouk you will find genres such as bélè (French islands), jing ping (Dominica), raggasoca (Barbados), and tambu (Dutch islands). And that’s not to mention bouyon and parang.

African drumming.

Fotolia

Medley of influences

This baffling array of musical forms is testimony to the creativity and individuality of each Caribbean island. It also reminds us of the many different influences - linguistic as well as musical - that have left their mark on the region. European colonizers from Britain, France, and Spain brought their music and instruments with them, recalled today in dances such as the quadrille of Martinique and Guadeloupe. From Africa came the drum-based rhythms and tradition of collective participation that underlie almost all contemporary styles in the region. Indian migrants contributed distinctive instruments and harmonies, especially in multicultural Trinidad. More recently, American jazz, rock and roll, rap, and hip hop have been incorporated and adapted into local forms, together with everything from Latin brass sections to Country & Western.

Caribbean music never stands still. Constantly borrowing and developing, it keeps pace with technological advances while remaining rooted in age-old traditions. In a region where so many cultural influences, good and bad, have been absorbed, fusion is a way of life. No wonder the Caribbean has a reputation for being one of the most exciting musical regions in the world.

Steel pan - a by-product of oil

You will hear steel pan throughout the region, but Trinidad justifiably claims not just to have invented it, but to be the world leader in playing it. There are still arguments over who it was who first realized the musical potential of a discarded oil drum in the 1930s. But there is no dispute that rhythm and percussion were already well established on the island. Predecessors included the tamboo bamboo orchestras, which pounded bamboo tubes on the ground or beat them with sticks (used instead of drums, which were banned by the British colonials as they thought they would encourage rioting) at folk dances, funeral wakes, and, of course, Carnival. Other percussionists resorted to biscuit tins, dustbins, and kitchen pots until the versatility of the imported oil drum, a feature of Trinidad’s booming petroleum industry, was discovered.

The steel pan is at the heart of the Caribbean sound and linked to Trinidad especially.

Trinidad & Tobago Tourism Development Company

Parang - a Christmas tradition

The build-up to Christmas in Trinidad wouldn’t be the same without the Afro-Spanish tradition known as parang (from the Spanish parar, meaning “to stop at” or “put up at somebody’s house”). The music is named after the roving performers who would move from house to house at the festive season with violins, cuatros, mandolins, guitars, and maracas, along with the African-descended box drum and box bass.

Deeply traditional in form, the styles include Spanish names such as aguinaldo, galerón, or paseo and are largely descended from the carol singing of 18th- and 19th-century Spanish settlers.

To begin with, steel pan and its players suffered a serious image problem. Associated with the slum areas of Port-of-Spain and tainted by regular violence, as gangs formed around competing bands to fight turf wars among themselves and against the police. It was only with the advent of corporate sponsorship and the commercialization of Carnival that the violence subsided. With the threat of companies withdrawing band sponsorship, a degree of peace broke out, and the previously violent rivalry subsumed into Panorama, the annual national steel band competition.

Calypso - voice of the people

The calypsonian was - and still is - the people’s orator. In post-Emancipation times, as people flocked to the city in search of jobs and away from the plantation, the calypsonian took on the traditional role of the chantwell, the improvising vocalist who used to sing boastful and comic songs during rural stick-fighting sessions. His function involved the dissemination of gossip, the spreading of news, and the mocking of those in authority. By the early 20th century, his performances were taking place in special tents, in front of discerning audiences who judged the artist’s topicality and originality.

A Calypsonian is… not only an articulator of the population, he is also a fount of public opinion. He expresses the mood of the people, the beliefs of the people. ” Mighty Chalkdust, Trinidadian teacher and Calypso Monarch

Brass is integral to soca, traditional carnival party music.

iStock

Today, little has changed, although there are now female performers, and subjects such as feminism and domestic abuse provide up-to-date inspiration. The calypsonian’s armory contains spontaneous improvisation, wit, and picong (biting, literally piquant, observations). His (or her) songs may be narrative, oratorical, or extemporaneous, but it’s likely that they will focus on sex, scandal, and what is known as “bacchanal.”

Calypso is part of Trinidad’s cultural lifeblood, which permeates through the whole of the Caribbean, and the climax comes each year at Carnival - or Crop Over in Barbados - which provides the background for fierce competition, lucrative prizes, and front-page headlines. Trinidad’s hall of fame includes legends such as Roaring Lion, Attila the Hun, and Lord Kitchener. The Mighty Sparrow is a Grenadian by birth, while Arrow (Alphonsus Cassell, who died in 2010), the singer of the 1980s’ worldwide hit Hot Hot Hot, came from Montserrat.

That song, in fact, is actually more soca than calypso, a faster-paced, dance-oriented style that has evolved from the fusion of Afro and Indian influences within the Trinidadian music scene (the word “soca” was originally “so-kah” - letters of the Hindi alphabet). Soca turned calypso into a more modern, danceable form, which appealed to younger generations.

And the musical evolution continues to gain momentum with the creation of raggasoca, the fusion of Jamaican dancehall and local soca.

Ceremonial tuk

One thriving aspect of Barbados’s annual Crop Over festival (historically held to mark the end of the cane-cutting season) is the tuk band. These percussive outfits are believed to date from as far back as the 17th century and later accompanied the island’s local friendly societies, known as “landships,” in ceremonies and outings. They are also thought to have modeled themselves on the marching bands of 18th-century British regiments.

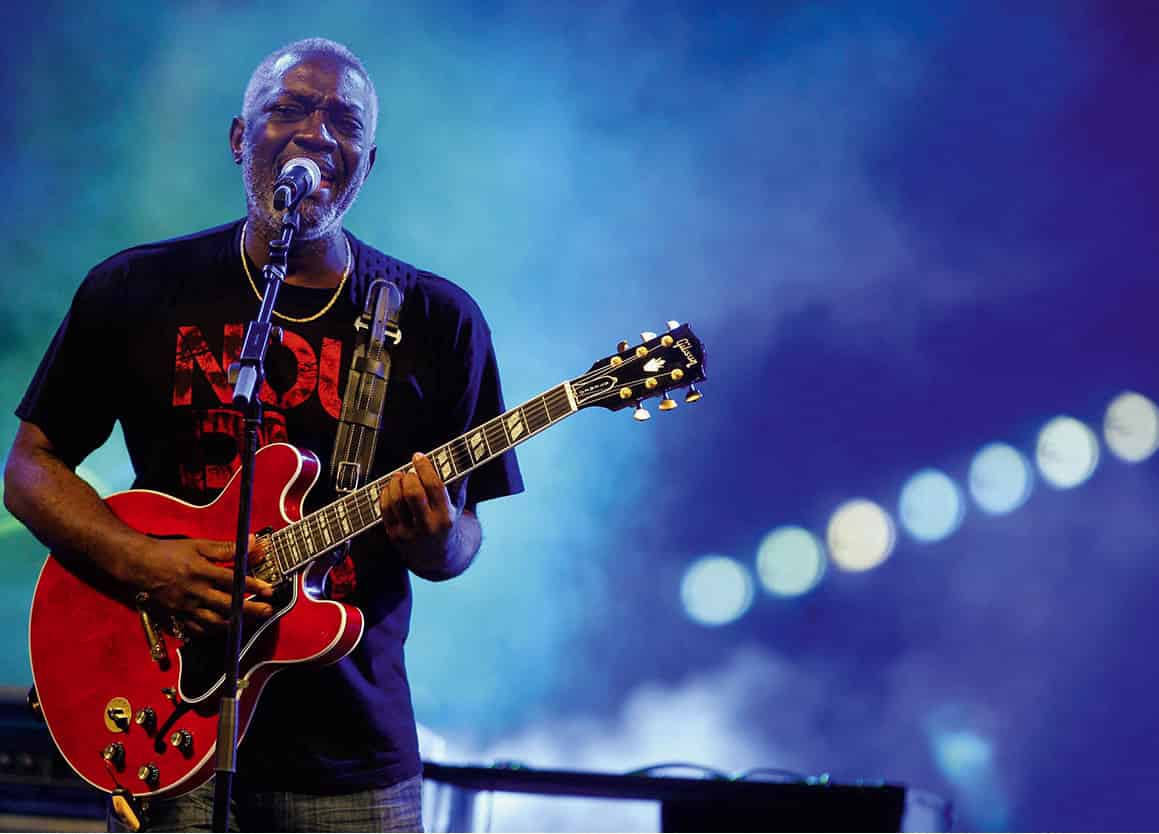

Kassav band-member Jacob Desvarieux performs at the Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algeria, 2009.

Corbis

Today’s tuk band is made up of bass, snare and kettle drums, a penny whistle or flute, and usually a triangle. Despite what might seem at first to be a limited musical range, the bands’ versatility is amazing and is often shown off in a wide repertoire of songs, covering the spectrum from European classical pieces to negro spirituals and current Billboard (Top Ten) hits. But it is the original, Caribbean-flavored material that brings out the best in the musicians, and thanks to the efforts of calypsonian Wayne “Poonka” Willcock and his group Ruk-a-Tuk International, tuk music has been staging something of a comeback in local festivals.

Round-up of music festivals

Many islands stage music festivals in addition to annual Carnival celebrations:

January St-Barths Music Festival (classic, folk, jazz)

February Mustique Blues Festival

March St John Blues Festival

April Holders Season, Barbados (opera); Carriacou Maroon & String Band Music Festival; Tobago Jazz Experience

May St Lucia Jazz and Arts Festival; Union Island Maroon Festival; Gospelfest, Barbados; Rapso Month, Trinidad; Grenada Drum Festival; Aruba Soul Beach Music Festival; BVI Music Festival; Terre-de-Blues Festival, Marie Galante

June St Kitts Music Festival; Antilles Music Festival, Martinique and Guadeloupe

July Gwo Ka Drum Festival, Guadeloupe

August Curaçao Salsa Tour Festival; Pic-o-De-Crop Calypso Finals, Barbados

September Curaçao North Sea Jazz Festival

October World Creole Music Festival, Dominica; Festival de las Américas, Aruba; Jazz Festival, Antigua and Barbuda; St Croix Music and Arts Festival, USVI

November Gwadloup’ Festival, Guadeloupe; Martinique Jazz Festival

December Carriacou Parang Festival; International Ilojazz Festival, Guadeloupe

Begin the beguine…

The earliest authentic style to have come from Martinique and Guadeloupe is generally agreed to be the beguine, its bolero rhythm a firm favorite among dance orchestras from the 1930s to the 1950s. Over the following two decades, the French Antillean soundscape underwent significant changes due to migration and freshly imported influences. An important new ingredient was brought by Haitian immigrants in the form of kadans or “cadence,” a subtle blend of musical accents, syncopation, and instrumental color derived from the fast-paced merengue, the national dance music of the neighboring Dominican Republic.

From kadans evolved zouk in the 1980s, a genre which was less a fad than a true phenomenon, reaching beyond the confines of the Caribbean to touch the continents of Africa, America, and Europe. Zouk trailblazers were the Guadeloupean band Kassav, whose founders, Pierre-Edouard Décimus and Jacob Devarieux, captured the festive mood and euphoria that marked the local vidé (spontaneous street carnival parade), and integrated old-style rhythmic dance elements into a modern good-time sound.

The success of Kassav and others marked the entry of French Caribbean music into the international marketplace. It also offered an original, rather than borrowed, model, including a long overdue emphasis on women’s voices, that appeals not only to the Caribbean as a whole, but to aficionados of dance music from all over the world.

Sandwiched between French/creole-speaking Martinique and Guadeloupe, the island of Dominica has long been influenced culturally and musically by the two French départements. But even if its rhythms are similar to those of its Gallic neighbors, there has still been room for innovation. Dominican cadence-lypso, commonly referred to as kadans, fuses Haitian konpa dance music with calypso, and the island’s long-serving popular Windward Caribbean Kulture (WCK) is a band specializing in bouyon, an eclectic mix of cadence-lypso and traditional jing ping, resulting in a compelling cocktail of pulsating drums à la digital and keyboards.

The late Trinidadian composer, Andre Tanker, was considered to be one of the great unsung musicians of the 20th century. His style influenced the island’s modern rock groups, such as Orange Sky and Jointpop.

Jazz fusions

The Afro-American art form of jazz has also found a home in the Caribbean, and has been mixed smoothly into the melting-pot of influences. Some 30 jazz festivals are held in the region each year. Meanwhile, musicians from the local region have tirelessly experimented with a variety of fusions which embrace New Orleans rhythms and their own distinctively Caribbean flavors.

A steel drummer and his gleaming pans.

iStock

Notable jazz exponents from the Lesser Antilles who can be seen at many of the festivals (see panel for a music festival round-up) include St Lucia’s Luther François, a gifted saxophonist and one of the region’s leading jazz composers; Barbadian saxophonist Arturo Tappin, who merges jazz with reggae; Ken “Professor” Philmore (Trinidad), who plays steel pan jazz; Nicholas Brancker (Barbados), who plays funk/jazz bass and keyboard; and Trinidadian Clive Zanda, who performs jazz inspired by calypso and folk music.