Fodor's Beijing (Full-color Travel Guide) (2015)

Main Table of Contents

Top Beijing Neighborhoods

Welcome to Beijing

Beijing Top Attractions

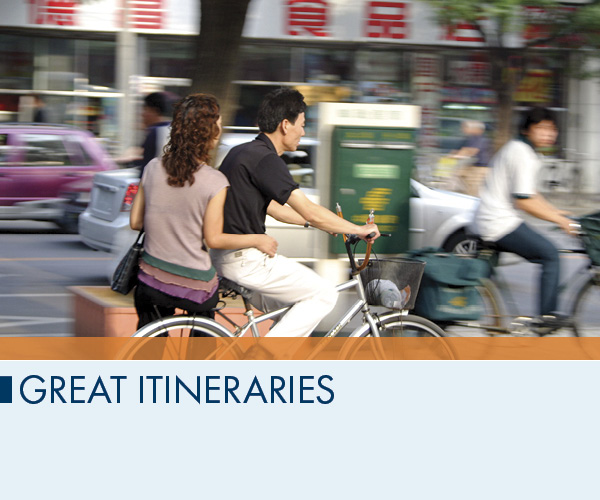

Great Itineraries

Top Things to Do in Beijing

A Brief History of Beijing

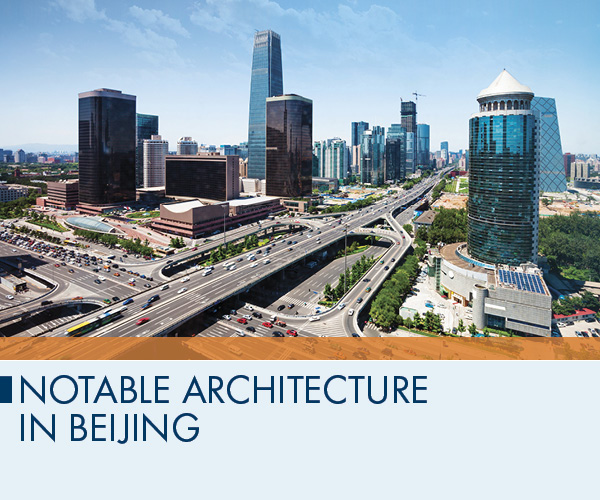

Notable Architecture in Beijing

Beijing Today

Beijing with Kids

Free (or Almost Free)

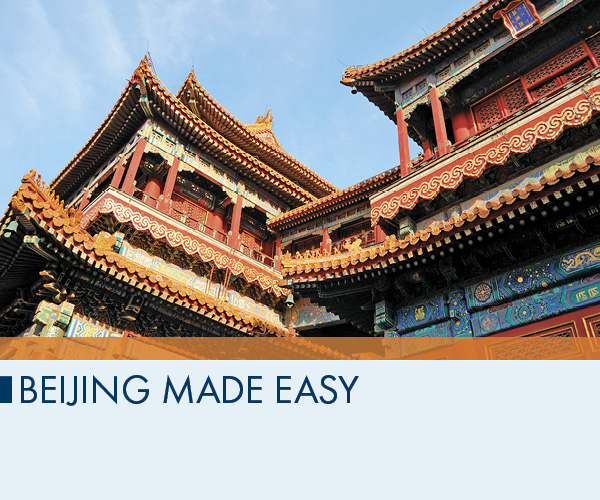

Beijing made Easy

Walking Beijing

Major Festivals

Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Next Map | Beijing Maps

Dongcheng District. This is where you’ll find the city’s top must-see attractions, including Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City, the Buddhist grandeur of the Lama Temple, and the hutong (alleyway) neighborhoods that surround the Drum and Bell towers. Since 2010 the district has also included Chongwen, southeast of the imperial palace. Once upon a time, this area teemed with the activity of markets, gambling parlors, and less savory establishments. A historically accurate (but sanitized) re-creation of old Qianmen Street recaptures some of that lost glory, although it can feel stale and lifeless. The Temple of Heaven features some of China’s most impressive imperial-era architecture.

Xicheng District. With Dongcheng, Xicheng encompasses the historically significant areas of Beijing that once lay inside the city walls; together the two make up the capital’s old inner core with the Forbidden City, home to the ruling imperial family, at its center. Six small lakes west of that key landmark lie at the heart of the district, which was once an imperial playground and is now home to China’s top leaders. Farther west, fashionable young Beijingers spend their hard-earned cash in the side-by-side shopping malls at Xidan. Tea lovers won’t want to miss Maliandao Tea Street.

Chaoyang District. This district wraps around many of the areas forming new Beijing. The skyline-altering Central Business District is in the south, the nightlife of Sanlitun is in the middle, and the 798 Art District (aka Dashanzi) and Olympic Park are in the north. This is today’s China, with lots of flash and little connection to the country’s 5,000 years of history.

Haidian District. The nation’s brightest minds study at prestigious Tsinghua and Peking universities in Beijing’s northwestern Haidian District. China’s own budding Silicon Valley, Zhongguancun, is also here. Head for one of the former imperial retreats at the Summer Palace, Fragrant Hills Park, or the Beijing Botanical Garden for some fresh air.

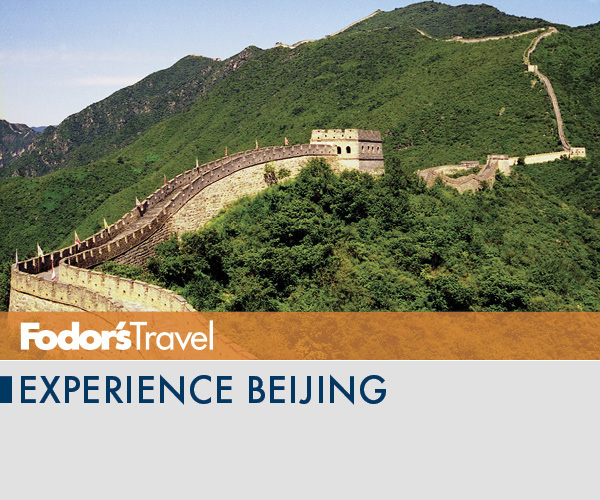

Side Trips from Beijing. No visit to the Beijing area is complete without a side trip to the Great Wall, that ancient defensive perimeter that’s just 75 km (47 miles) to the north. Those who have time for a longer excursion could also head to the old imperial retreat of Chengde, now a vibrant city 230 km (143 miles) to the northeast.

Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

When to Go | Getting Around | Getting Oriented | Etiquette | Street Vocabulary

WHEN TO GO

The best time to visit Beijing is spring or early fall; the weather is better and crowds are a bit thinner. Book at least one month in advance during these times of year. In winter Beijing’s Forbidden City and Summer Palace can look fantastical and majestic, especially when their traditional tiled roofs are covered with a light dusting of snow and there are few tourists.

The weather in Beijing is at its best in September and October, with a good chance of sunny days and mild temperatures. Winters are very cold, but it seldom snows. Some restaurants may be poorly heated, so bring a warm sweater. Late April through June is lovely. In July the days are hot and excruciatingly humid with a good chance of rain. Spring is also the time of year for Beijing’s famous dust storms. Pollution is an issue year-round but particularly in winter months.

Avoid travel during Chinese New Year and National Day. Millions of Chinese travel during these weeks, making it difficult to book hotels, tours, and transportation. If you must visit during Chinese New Year, be sure to check out the traditional temple fairs that take place at religious sites around the city.

GETTING AROUND

On Foot: Although traffic and modernization have put a bit of a cramp in Beijing’s walking style, meandering on foot remains one of the best ways to experience the capital—especially the old hutong neighborhoods.

By Bike: Some 1,000 new automobiles take to the streets of the capital every day, bringing the total to more than 5 million vehicles. All this competition has made biking less pleasant and more dangerous. Fortunately, most streets have wide, well-defined bike lanes often separated from other traffic by an island. Bikes can be rented at many hotels and next to some subway stations. (And the local government has said it will reduce the number of new license plates by 40 percent by 2017).

By Subway: The subway is the best way to avoid Beijing’s frequent traffic jams. With the opening of new lines, Beijing’s subway service is increasingly convenient. The metropolitan area is currently served by 14 lines as well as an express line to the airport. The subway runs from about 5 am to midnight daily, depending on the station. Fares are Y2 per ride for any distance and transfers are free. Stations are marked in both Chinese and English, and stops are also announced in both languages. Subways are best avoided during rush hours, when severe overcrowding is unavoidable.

By Taxi: The taxi experience in Beijing has improved significantly as the city’s taxi companies gradually shift to cleaner, more comfortable new cars. In the daytime, flag-fall for taxis is Y13 for the first 3 km (2 miles) and Y2 per km thereafter. The rate rises to Y3 per km on trips over 15 km (8 miles) and after 11 pm, when the flag-fall also increases to Y14. At present, there’s also a Y1 gas surcharge for any rides exceeding 3 km (2 miles). WARNING: Be sure to check that the meter has been engaged to avoid fare negotiations at your destination. Taxis are easy to hail during the day, but can be difficult during evening rush hour, especially when it’s raining. If you’re having difficulty, go to the closest hotel and wait in line there. Few taxi drivers speak English, so ask your hotel concierge to write down your destination in Chinese.

GETTING ORIENTED

At the heart of Beijing lies the Forbidden City, home of the emperors of old, which is adjacent to the secretive and off-limits Zhongnanhai, home of China’s current leadership. The rest of the city revolves around this core area, with a series of concentric rings roads reaching out into the suburbs, and most major arteries running north-south and east-west. As you explore Beijing, you’ll find that taxis are often the best way to get around. However, if the subway goes where you’re headed, it’s often a faster option than dealing with traffic.

The city is divided into 18 municipal and suburban districts (qu). Only four of these districts are the central stomping grounds for most visitors; our coverage focuses on them. The most important, Dongcheng (“east district”) encompasses the Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square, Wangfujing (a major shopping street), the Lama Temple, and many other historical sites dating back to imperial times. Xicheng (“west district”), directly west of Dongcheng, is a lovely lake district that includes Beihai Park, a former playground of the imperial family, and a series of connected lakes bordered by willow trees, courtyard-lined hutong, and lively bars. Chaoyang is the biggest and busiest district, occupying the areas north, east, and south of the eastern Second Ring Road. Because it lies outside the Second Ring Road, which marked the eastern demarcation of the old city wall, there’s little of historical interest here, though it does have many of the city’s top hotels, restaurants, and shops. Chaoyang is also home to the foreign embassies, multinational companies, the Central Business District, and the Olympic Park. Haidian, the district that’s home to China’s top universities and technology companies, is northwest of the Third Ring Road; it’s packed with shops selling electronics and students cramming for their next exam.

ETIQUETTE

It’s respectful to dress modestly at religious sites: cover your shoulders and don’t wear short skirts or shorts. Keep in mind that authorities are very sensitive about public behavior in Tiananmen Square, which teems with plainclothes state security officers at all times.

STREET VOCABULARY

Here are some terms you’ll see over and over again. These words will appear on maps and street signs, and they’re part of the name of just about every place you go:

Dong is east, xi is west, nan is south, bei is north, and zhong means middle. Jie and lu mean street and road respectively, and da means big, so dajie equals avenue.

Gongyuan means park. Jingshan Park is, therefore, also called Jingshan Gongyuan.

Nei means inside and wai means outside. You will often come across these terms on streets that used to pass through a gate of the old city wall. Andingmen Neidajie, for example, is the section of the street located inside the Second Ring Road (where the gate used to be); Andingmen Waidajie is the section outside the gate.

Qiao, or bridge, is part of the place name at just about every entrance and exit on the ring roads.

Men, meaning door or gate, indicates a street that once passed through an entrance in the old wall that surrounded the city until it was mostly torn down in the 1960s. The entrances to parks and some other places are also referred to as men.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

FORBIDDEN CITY

The Forbidden City has been home to a long line of emperors, beginning with Yongle, in 1420, and ending with Puyi (made famous by Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 film The Last Emperor), who was forced out of the complex by a warlord in 1924, over a decade after he abdicated his throne. This is the largest palace in the world, as well as the best preserved, and offers the most complete collection of imperial architecture in China.

LAMA TEMPLE

The smell of incense permeates one of the few functioning Buddhist temples in Beijing. When Emperor Yongzheng took the throne in 1722, his former residence was converted into this temple. During the Qianlong Period (1736-95) it became a center of the Yellow Hat sect of Tibetan Buddhism. At its high point, 1,500 lamas lived here. The Pavilion of Ten Thousand Fortunes (Wanfu Ge) has a 60-foot tall statue of the Maitreya Buddha carved from a single piece of sandalwood.

SUMMER PALACE

This beautiful complex, surrounding a large lake, dates back eight centuries. Notable sights include the Long Corridor (a covered wooden walkway) and the Hall of Benevolent Longevity. At the west end of the lake is the famous Marble Boat that Cixi built with money intended to create a Chinese navy. The palace, which served as an imperial summer retreat, was ransacked by British and French soldiers in 1860 and later burned by Western soldiers seeking revenge for the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 (don’t confuse this with Yuan Ming Yuan, the Old Summer Palace, which was almost completely destroyed by foreign soldiers in 1860).

CONFUCIUS TEMPLE

This temple, with its towering cypress and pine trees, offers a serene escape from the crowds at the nearby Lama Temple. This is the second-largest Confucian temple in China, after the one in Qufu, the master’s hometown in Shandong Province. First built in the 14th century, the Confucius Temple was renovated in the 18th century.

TEMPLE OF HEAVEN

The 15th-century Temple of Heaven is one of the best examples of religious architecture in China. The complex contains three main buildings where the emperor, as the “Son of Heaven,” offered semiannual prayers. The sprawling, tree-filled complex is a pleasant place for wandering: watch locals practicing martial arts, playing traditional instruments, and enjoying ballroom dancing on the grass.

TIANANMEN SQUARE

Walking beneath the red flags of Tiananmen Square is a quintessential Beijing experience. The political heart of modern China, the square covers 100 acres, making it the world’s largest public square. It was here, from the Gate of Heavenly Peace, that Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, and it is here that he remains, embalmed in a mausoleum constructed in the square’s center. Many Westerners think only of the massive student demonstrations here in 1989, but it has been the site of protests, rallies, and marches for close to 100 years.

GREAT WALL OF CHINA

Touristy it may be, but make time to see it while you’re in Beijing. The closest location, at Badaling, is a one-hour drive away—you may recognize some of the views and angles here from their frequent use in photo ops.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

The Italian priest Matteo Ricci arrived in Beijing in 1598. His efforts to understand the capital led him to stay until his death, 12 years later. You, on the other hand, have to get back home before the week’s out. But while you may not have the luxury of time on your side, you do have the advantage of something Ricci could only dream of: our handy guide to the best one-, three- and five-day tours. Hit the best; forget the rest.

BEIJING IN ONE DAY

It’s impossible to see everything Beijing has to offer in a single day. Still, if that’s all you’ve got, you can cover a lot of the key sights if you go full steam. The geographical center of Tiananmen Square is on most people’s must-do list. Fundamentally, however, it’s just a big square. Make the trip worthwhile by being first in line for the Mao Zedong Memorial Hall at 8 am (early birds may want to take in the pomp of the flag-raising ceremony held each dawn, which takes place around 7 am during winter months). Within this stern-looking building, which dominates the center of the square, you’ll find the Chairman’s embalmed remains. Remember to take your passport (and deposit any bags at the designated storage facility before lining up).

Follow this curious experience by heading to the north side of the square to the Gate of Heavenly Peace, which marks the entrance to the Forbidden City, a sight that needs no introduction. This may be the home of the emperors, but the mark of Mao remains. You’ll have to pass under his portrait to make your way in. Exploring this imperial palace takes hours. The peripheral courtyards provide a welcome escape if the crowds become too trying. Save some energy for the gentle hike to the top of the hill in Jingshan Park opposite the north exit of the Forbidden City. Too many run out of gas and skip the stunning views.

Reward yourself with a cracking good lunch deal at Temple Restaurant Beijing: fine dining in a 600-year-old temple. Take it easy in the afternoon with a stroll around Beihai Park—a former imperial garden—before renting a boat for a lazy time on its large lake. It’s then a half-hour walk (or short cab ride) to Wangfujing, a street made for shopping. The snack stalls here are particularly fun, especially if you’re brave enough to try the likes of starfish or scorpion on a stick.

Ride the subway two stops from Wangfujing to Tiananmen West to round off the night with some world-class classical music at the architectural wonder that is the National Center for Performing Arts (also known as the Egg).

BEIJING IN THREE DAYS

Start with our one-day tour as above. But then what to do with your other two days? Well, it’d be foolish to come all the way to China and not visit the Great Wall. There’s no getting around the fact, however, that this requires a full day. The Badaling section is closest; the wall at Mutianyu is better—both are somewhat “touristy.” If that bothers you then you may want to hike one of the “wilder” sections of the Great Wall. It’s possible, although not recommended, to do this independently. You’re better off hiring a guide. Our favorite is Tony Chen at Stretch-a-leg Travel (www.stretchalegtravel.com). Once you’re back in town, dine on Peking duck for dinner. Take your pick from Da Dong Roast Duck, Made in China, or Duck de Chine—three of the best places in town to try Beijing’s signature dish.

For your final day get ready to explore the capital’s historical hutong—the fast-disappearing network of ancient alleyways that were the lifeblood of old Peking. Start at the atmospheric Lama Temple (easily reached via Line 2). This is the most important functioning Buddhist temple in Beijing and it remains full of life. Drop by the nearby Confucius Temple, dedicated to China’s great sage, before wandering through the area’s atmospheric hutong—Wudaoying and Guozijian are of particular interest. Wind your way through the area’s alleys en route to the Drum and Bell towers, which provided the city’s official means of timekeeping up until 1924. It should be a half-hour walk. But don’t worry if you get lost in the lanes, as that’s all part of the adventure. Climb either tower for a fabulous view. You’ll see the nearby Houhai lakes to the west—a good spot to rent a boat in summer or go ice-skating in winter. If you want to explore the area on foot, then head to the Silver Ingot Bridge instead, before finishing your day in the buzzing hutong around Nanluoguxiang (1 km [½ mile] east of Houhai), packed with boutiques, bars, and restaurants.

BEIJING IN FIVE DAYS

Lucky enough to have five days in the capital? Follow our three-day tour, then spend your remaining time taking in Beijing’s glorious mix of old and new, from temples and palaces to contemporary art and shopping galore. Kick off day four with an early start down south at the beautiful Temple of Heaven. This is where the emperors used to pray for prosperity. Today you’ll find it populated with the city’s older residents, who can often be found practicing tai chi or singing songs here.

Once done with this impressive imperial sight, hop into a cab for the 5-km (3-mile) journey east to the Panjiayuan Antiques Market, which is a great place to pick up presents and mementos. Traders here sell everything from Chinese chess sets and delicate porcelain to Mao alarm clocks and traditional instruments. Another cab ride will take you to the 798 Art District up in the northeast part of the city (a half-hour drive in good traffic; an hour in bad), which is a wonderful way to spend an afternoon—avoid Monday, however, when most galleries here are shut. Formerly a factory complex, the area is now a thriving arts hub. The best gallery to visit is the UCCA, but the proliferation of little shops, cafés, and bars make this a great place to hang out even if you’re not into art.

Head back to downtown Sanlitun for sundown. Shopaholics can squeeze in some last-minute spending at Yashow, an indoor market full of cheap clothes, bags, and such; bargain harder than you ever have before. Spend the evening soaking up Sanlitun’s bustling nightlife. Avoid the main “bar street” and check out the watering holes and eateries in Village Sanlitun instead. Get out of the city on your final day. Spend the morning back in imperial China at the striking Summer Palace up in Beijing’s northwest corner. Combine the trip with the ruins of nearby Yuan Ming Yuan, the Old Summer Palace. You may want to spend the afternoon at the Fragrant Hills Park—popular among residents escaping the urban grind—or the Beijing Botanical Garden. Both are even farther west than the Summer Palace and visiting just one will take the rest of the day.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

SEE THE CITY BY BIKE

Four wheels may be good for getting around, but two wheels are better. The capital demands to be discovered by bicycle. Unlock a different perspective on the city by renting a bike from Serk (www.serk.cc) and spending a day in the saddle. Or take a tour with Bike Beijing (www.bikebeijing.com).

DANCE THE NIGHT AWAY

Beijing’s older inhabitants love to dance wherever they can set up a sound system: parks, squares, streets, and underpasses. One of the best places to join in is outside Saint Joseph’s Cathedral on Wangfujing. Hundreds of movers and groovers gather here every night. Get yourself down there and sway along to the sounds.

TRAIN IN TAI CHI

You’ll see plenty of folk practicing this gentle Chinese martial art throughout town. Our favorite way to train is with Bespoke Beijing (www.bespoke-beijing.com), who can arrange a private hour-long class among the trees of the Temple of Heaven. It’s led by a tai chi master who trained at the Shaolin Temple as a child.

EAT SCARY SNACKS

There’s some wonderful food to be had here. There are also some truly terrifying dishes to try if you’re feeling brave. The likes of scorpions on a stick are served up at Wangfujing Snack Street. To be safer, choose carts with a high turnover. For something less weird but just as savory, head to Xiaoyou Hutong, where a dozen eateries, refugees from urban renewal, serve traditional specialties inside a renovated courtyard house.

GO FOR GOLD AT THE OLYMPIC PARK

If you have the time, a visit to the Olympic Park, just north of the Fourth Ring Road, is a chance to see the starkly modern side of China—the face it wants the world to see. The Bird’s Nest stadium dominates the landscape, while the Water Cube, the venue for Michael Phelps’s extraordinary eight gold medals, has been turned into a thrilling water park, complete with a lazy river and slides and rides for all ages.

MEDITATE WITH MONKS

If a visit to the downtown Lama Temple awakens your spiritual side, then a weekend away staying with monks at Chaoyang Temple—an hour or two outside the city in Huairou District—may be the key to reaching real enlightenment. A crash course in Zen Buddhism awaits the curious (www.90travel.com).

ENJOY A NIGHT AT THE OPERA

Peking opera is regarded as one of the country’s cultural treasures. If you want to check out this unique form of traditional Chinese theater then you won’t get a better opportunity than in its birthplace. Be warned: the sonic style may not be music to all ears, but finding out is all part of the fun.

HIKE THE GREAT WALL

There’s more than one way to see the world’s most famous wall. Abandon the tourist trail and escape the crowds with Beijing Hikers (www.beijinghikers.com). This walking group runs regular trips to some of the more interesting areas of the Great Wall. Join them to explore unrestored sections most tourists don’t even know exist.

ROCK OUT

Beijing is the beating heart of China’s burgeoning rock scene. Join the city’s hipsters and rock kids at one of the many gigs on the local circuit. MAO Live House (www.mao-music.com) and Yugong Yishan (www.yugongyishan.com) are two of the best venues to crash if you’re out cool hunting.

HAVE A BEIJING TEA PARTY

Fans of a nice cup of cha won’t want to miss Maliandao—the largest tea market in north China. For a more personal experience you should head to Fangjia Hutong, where you’ll find Tranquil Tuesdays (www.tranquiltuesdays.com), a local social enterprise dedicated to China’s tea culture. Its founder, Charlene Wang, personally sources the nation’s best natural leaves for sale. Call ahead for an appointment.

CHECK OUT THE STUNNING STUNTS

China’s acrobats train harder than any others. The results, as seen in many of the shows across town, are guaranteed to elicit oohs and aahs. The show at the Chaoyang Theater is the most conveniently located, and has an excellent Japanese whisky bar attached.

TAKE A LOOK DOWN THE LANES

The capital’s ancient alleys are there for all to explore. Walk or cycle, it’s up to you. But for a completely different view of things we recommend booking a tour with Beijing Sideways (www.beijingsideways.com) who will whiz you off to hard-to-find places deep in the hutong network while riding aboard the sidecar of a vintage motorbike.

HONE YOUR HAGGLING SKILLS

It’s hard to resist: so much to bargain for in Beijing markets, and so little time! Visit outdoor Panjiayuan (aka the Dirt Market), where some 3,000 vendors sell antiques (both legitimate and otherwise), Cultural Revolution memorabilia, and handicrafts from across China. Looking for knockoffs? The Silk Market is popular with tourists, but local expats prefer Yashow Market, which generally has better prices.

LET THE GAMES BEGIN

Basketball is so popular in China that it’s practically the national sport. Cheer on the Beijing Ducks (led to their first title in 2012 by ex-NBA star Stephon Marbury) at their nest in Shijingshan District. It is, however, quite the trek. For an easier sporting fix, go support the soccer team, Beijing Guoan, at the Workers’ Stadium in Sanlitun.

GET SUITED UP

London’s got Savile Row. Beijing’s got top tailoring for a fraction of the dough. Where you go depends on how much cash you want to splash, but you can’t go wrong at Wendy’s (on the third floor of Yashow Market). There’s no way you’ll get made-to-measure shirts of this quality for such a low price back home.

GET COOKING

If you dine right (with our help, we hope), you’ll eat so well that you’ll want to take the secrets of these tasty Chinese treats home. Hurry down to The Hutong (www.thehutongkitchen.com) for its packed calendar of cooking classes, which cover everything from making dumplings to creating sizzling Sichuan dishes.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

IN THE BEGINNING

Since the birth of Chinese civilization, different towns of varying size and import have stood at or near the site of today’s Beijing. For example, a popular local beer, Yanjing, is named for a city-kingdom based here 3,000 years ago. With this in mind, it’s not unreasonable to describe Beijing’s modern history as beginning with the Jin Dynasty, approximately 800 years ago. Led by nine generations of the Jurchen tribe, the Jin Dynasty eventually fell into a war against the Mongol hordes.

THE MONGOLS

Few armies had been able to withstand the wild onslaught of the armed Mongol cavalry under the command of the legendary warrior Genghis Khan. The Jurchen tribe proved no exception, and the magnificent city of the Jin was almost completely destroyed. A few decades later, in 1260, when Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, returned to use the city as an operational base for his conquest of southern China, reconstruction was the order of the day. By 1271 Kublai Khan had achieved his goal, declaring himself emperor of China under the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), with Beijing (or Dadu, as it was then known) as its capital.

The new capital was built on a scale befitting the world’s then superpower. Its palaces were founded around Zhonghai and Beihai lakes. Beijing’s current layout still reflects the Mongolian design.

THE MINGS

About 100 years after the Mongolians settled Beijing they suffered a devastating attack by rebels from the south. The southern roots of the quickly unified Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) deprived Beijing of its capital status for half a century. But in 1405, the third Ming emperor, Yongle, began construction on a magnificent new palace in Beijing: an enormous maze of interlinking halls, gates, and courtyard homes, known as the Forbidden City.

The Ming also contributed mightily to China’s grandest public works project: the Great Wall. The Ming Great Wall linked or reinforced several existing walls, especially near the capital, and traversed seemingly impassable mountains. The majority of the most spectacular stretches of the wall that can be visited near Beijing were built during the Ming Dynasty. But wall building drained Ming coffers and, in the end, failed to prevent Manchu horsemen from taking the capital and the rest of China in 1644.

AND FINALLY, THE QINGS

This foreign dynasty, the Qing, inherited the Ming palaces, built their own retreats (most notably, the “old” and “new” summer palaces), and perpetuated feudalism in China for another 267 years. In its decline, the Qing proved impotent to stop humiliating foreign encroachment. It lost the first Opium War to Great Britain in 1842 and was forced to cede Hong Kong “in perpetuity” as a result. In 1860 a combined British and French force stormed Beijing and razed the Old Summer Palace.

MAO TAKES THE REINS

After the Qing crumbled in 1911, its successor, Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party, struggled to consolidate power. Beijing became a cauldron of social activism. On May 4, 1919, students marched on Tiananmen Square to protest humiliations in Versailles, where Allied commanders negotiating an end to World War I gave Germany’s extraterritorial holdings in China to Japan. Patriotism intensified, and in 1937 Japanese imperial armies stormed across Beijing’s Marco Polo Bridge to launch a brutal eight-year occupation. Civil war followed close on the heels of Tokyo’s 1945 surrender and raged until the Communist victory. Chairman Mao himself declared the founding of a new nation from the rostrum atop the Gate of Heavenly Peace on October 1, 1949.

Like Emperor Yongle, Mao built a capital that conformed to his own vision. Soviet-inspired structures rose up around Tiananmen Square. Beijing’s historic city wall was demolished to make way for a ring road. Temples and churches were torn down, closed, or turned into factories during the brutal upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966 and lasted until Mao’s death, in 1976.

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND THE CITY

In more recent years the city has suffered most, ironically, from prosperity. Many ancient neighborhoods have been bulldozed to make room for glitzy commercial developments. A growing commitment to preservation has very slowly begun to take hold, but chai (to pull down) and qian (to move elsewhere) remain common threats across the capital.

Today Beijing’s some 20 million residents—including 7 million migrant workers—enjoy a fascinating mix of old and new. Early morning tai chi enthusiasts, ballroom and disco dancers, old men with caged songbirds, and amateur Beijing opera crooners frequent the city’s many parks. Cyclists clog the roadways, competing with cars on the city’s thoroughfares. Beijing traffic has gone from nonexistent to nightmarish in less than a decade.

As the seat of China’s immense national bureaucracy, Beijing carries a political charge. The Communist Party, whose self-described goal is “a dictatorship of the proletariat,” has yet to relinquish its political monopoly.

COMMUNISM TODAY

In 1989 student protesters in Tiananmen Square dared to challenge the party. The government’s harsh response remains etched in global memory, although younger Chinese people are likely never to have heard of that seismic moment due to the taboo nature of the subject and the country’s strict censorship laws. More than 25 years later, secret police still mingle with tourists on the square. Mao-style propaganda persists. Slogans that preach unity among China’s national minorities and patriotism still festoon the city on occasion. Yet as Beijing’s robust economy—now the second largest in the world—is boosted even further by the government’s continuing embrace of “a socialist market economy” (read: state-sanctioned capitalism) and the massive influx of foreign investment, such campaigns appear increasingly out of touch with the iPhone-wielding generation. And so there is now a more modern side to the city to consider, one perhaps best encapsulated by the drastic changes continually being made to both skyline and streets. The result is an incongruous mixture of new prosperity and throwback politics: socialist slogans adorn shopping centers selling everything from Big Macs to Louis Vuitton. In modern Beijing the ancient and the sparkling new are constantly colliding.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

The 2008 Summer Olympics changed the look of the Chinese capital like never before. Whole city blocks were razed to make way for modern buildings, new hotels, and state-of-the-art sports facilities. The subway system has expanded from just two to 16 lines, with four more under construction. Just about everywhere you look you’ll find signs of the feverish development boom that didn’t end when the games left off. But the focus has switched from iconic Olympic venues and government-initiated state buildings—such as the extraordinary headquarters for the state-run TV network—to more commercially minded projects looking to mix architectural innovation with office space and shopping malls. Yes, China is rightly proud of its 5,000 years of history, but in terms of looking forward and not back, Beijing’s 21st-century projects—many designed by top international architects—are impressive to say the least.

BEIJING CAPITAL INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, TERMINAL 3

With its lantern-red roof shaped like a dragon, Beijing’s airport expansion embraces traditional Chinese motifs with a 21st-century twist: its architect calls it “the world’s largest and most advanced airport building.” This single terminal contains more floor space than all the terminals at London’s Heathrow Airport combined. Construction started in 2004 with a team of 50,000 workers and was completed a few months before the Olympic Games.

Architect: Norman Foster, the preeminent British architect responsible for global icons such as Hong Kong’s widely respected airport, London’s “Gherkin” skyscraper, and the Reichstag dome in Berlin.

BEIJING LINKED HYBRID

With 700 apartments in eight bridge-linked towers surrounding a plethora of shopping and cultural options, including Beijing’s best art-house cinema, the Linked Hybrid has been applauded for parting from the sterility of typical Chinese housing. The elegant complex also features an impressive set of green credentials such as geothermal heating and a wastewater recycling system. | Adjacent to the northeast corner of the 2nd Ring Rd.

Architects: New York-based Steven Holl—who has won awards for his contemporary art museum in Helsinki, Finland, and innovative “horizontal skyscraper” in Shenzhen—and Li Hu, who helped design China’s first contemporary museum in Nanjing.

CCTV (CHINA CENTRAL TELEVISION) HEADQUARTERS

Perhaps the most remarkable of China’s new structures, the central television headquarters twists the idea of a skyscraper quite literally into a 40-story-tall gravity-defying loop. What some have called the world’s most complex building (and what locals have nicknamed “The Big Pants”) is also, with a $1.3 billion price tag, one of the world’s priciest. An accompanying building that was to include a hotel, a visitor center, and a public theater was destroyed after it caught on fire during the Chinese New Year fireworks display in 2009. Due to the complex engineering involved. the secondary building remains under reconstruction. | 32 Dong San Huanzhonglu (32 E. 3rd Ring Middle Rd.).

Architects: Rem Koolhaas (a Dutch mastermind known for his daring ideas and successful Seattle Public Library) and Ole Scheeren (Koolhaas’s German protégé).

NATIONAL STADIUM (“THE BIRD’S NEST”)

Despite the heft of 42,000 tons of steel bending around its center, this 80,000-seat stadium somehow manages to appear delicate rather than clunky, with its exterior lattice structure resembling the twigs of an elegant nest—hence the nickname. Now used occasionally for events such as visiting soccer games and concerts, it’s an absolutely massive structure, and must be seen to be believed. | Beijing Olympic Park at Bei Si Huanlu (N. 4th Ring Rd.).

Architects: The Herzog & de Meuron firm of Switzerland, which won the prestigious Pritzker Prize for converting London’s Bankside Power Station into the much-loved Tate Modern art gallery. The stadium also saw the involvement of leading Chinese artist Ai Weiwei as artistic consultant.

NATIONAL AQUATICS CENTER (“THE WATER CUBE”)

The translucent skin and hexagonal high-tech “pillows” that define this 17,000-seat indoor swimming stadium create the impression of a building fashioned entirely out of bubbles. The structure is based on the premise that bubbles are the most effective way to divide a three-dimensional space—and they help save energy and keep the building earthquake-proof. The center has now been turned into a public aquatics center and water park. | Beijing Olympic Park.

Architects: PTW Architects, the Australian firm that cut its teeth on venues for the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney.

NATIONAL CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (“THE EGG”)

Located near Tiananmen Square, and completely surrounded by water, this bulbous opera house—a spectacular dome of titanium and glass known locally as “The Egg”—might cause passersby to think that some sort of spaceship has landed in the capital. Its close proximity to the Forbidden City, and its soaring costs (more than $400 million), earned it a hostile welcome among some Chinese architects, although it has now been embraced by the city thanks to its excellent program of classical music and refreshingly unconventional appearance. | Xi Chang’an Jie (just west of Tiananmen Sq.).

Architect: French-born Paul Andreu, who designed the groundbreaking Terminal 1 of Paris’s Charles de Gaulle airport in 1974, as well as working on the French capital’s La Grande Arche.

GALAXY SOHO

Consisting of four huge amorphous globes, wrapped in curved white panels and flowing glass curtain walls, this mixed-use complex from one of the country’s largest property developers (SOHO China) continues the futuristic theme of The Egg. Opened at the end of 2012, it’s quite the statement: a bold continuation of the architectural ambition initiated by the Games, now transferred to the more functional world of office and retail space. Welcome to Beijing’s next chapter. | E. 2nd Ring Rd. (next to Chaoyangmen subway station).

Architect: Iraqi-British starchitect Zaha Hadid—the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize—who made a splash in China prior to this with her opera house in the southern city of Guangzhou.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

The air is dirty, the traffic is horrendous, and almost nobody speaks more than a word or two of English—so what makes Beijing one of the world’s top destinations?

Old and new live together. The flat skyline of Beijing, punctuated only by imposing ceremonial towers and the massive gates of the city wall, is lost forever. But still, standing on Coal Hill and looking south across the Forbidden City—or listening to the strange echo of your voice atop an ancient altar at the Temple of Heaven—you can’t help but feel the weight of thousands of years of history. It was here that Marco Polo supposedly dined with Kublai Khan and his Mongol hordes; that Ming and Qing emperors ruled over China from the largest and richest city in the world; and that Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. Much of Beijing’s charm comes from the juxtaposition of old and new. When you’re riding a taxi along the Third Ring Road it may seem that the high-rise apartments and postmodern office complexes stretch on forever. They do, almost, but tucked in among the glass and steel are elaborate temples exuding wafts of incense, and tiny alleyways where old folks still gather in their pajamas every evening to play cards and drink warm beer. Savoring these small moments is the key to appreciating today’s Beijing.

There are interesting things to eat. If you really love General Tso’s chicken back at your local Chinese take-out place, you may want to skip Beijing altogether. Many a returned visitor has complained of being unable to enjoy the bland stuff back home after experiencing the myriad flavors and textures of China’s regional cuisines. From the mouth-numbing spices of Sichuan, to the delicate presentation of an imperial banquet, or the cumin-sprinkled kebabs of China’s Muslim west, Beijing has it all. If you’re looking for the ultimate in authenticity, dine at a restaurant attached to one of the city’s provincial representative offices, where the chefs and ingredients are imported to satisfy the taste buds of bureaucrats working far from home. The crispy skin and tender flesh of the capital’s signature dish, Peking duck, is on everyone’s must-eat list. But don’t worry if you tire of eating Chinese food three times a day. As Beijing has grown rich in recent years, Western and fusion cuisine offerings have improved greatly, with everything from French to Middle Eastern to Texas-style barbecue now available. If you’re looking for a special—although somewhat expensive—night out, try Temple Restaurant Beijing, where East meets West in the grounds of a 600-year-old temple, now a dining destination for contemporary European cuisine.

This is a global city. Prestige projects such as the National Center for the Performing Arts (“The Egg”), the new CCTV building, and a massive subway expansion are clearly aimed at showing the world that China is playing with the big boys. The Chinese are fiercely patriotic, and antiforeign demonstrations occasionally break out when the country’s collective pride is insulted. The official version of Chinese history taught in schools emphasizes the nation’s suffering at the hands of foreign colonial powers during the 19th and 20th centuries, and the subsequent Communist “liberation.” Still, you’ll find most Beijingers infinitely polite and generally curious about your life back home. People here aren’t quite sure what to make of their new surroundings, and they’re as interested in finding out about you as you are about them. So strike up a conversation (with your hands if necessary), but be sure to go easy on the politics.

Beijing is a happening destination. Newcomers could be forgiven for seeing bustling Shanghai as China’s go-to place. But anyone who has spent a little time in the capital swears that it’s the soul of the country. People from all over China, and the world, are drawn here by the many opportunities the city offers, the cultural fervor, and the chance to reinvent themselves. There’s an unusual freedom here that has made Beijing the creative center of the country, and this attracts the creative elite from all around the world. Art galleries have sprung up in hotels, courtyard houses, shut-down factories, and even an ancient watchtower. This is where serious Chinese musicians must come to make it or break it, and even no-nonsense businessmen see Beijing as a mecca because they believe the challenges—and rewards—are greater here.

Interesting Facts About the Capital City

With around 20 million residents, Beijing is vying with Shanghai to become the largest city in China.

The city has existed in various forms for at least 2,500 years, but Homo erectus fossils prove that humans have lived here for 250,000 years.

Beijing was once surrounded by a massive city wall constructed during the Ming Dynasty. Of its 16 original gates, only three remain standing. The wall was demolished in 1965 to make way for the Second Ring Road.

At 100 acres, Tiananmen Square is the largest urban square in the world; during the Cultural Revolution, as many as 1 million people were able to stand on numbered spaces for huge rallies with Chairman Mao.

Despite major efforts to improve Beijing’s air quality, pollution levels in the city remain several times higher than World Health Organization limits. Adding to the problem, a single sandstorm (usually arriving in spring) can drop tens of thousands of tons of dust onto the city in mere hours.

Beijingers love to brew, and more than 1,000 tea shops can be found along Maliandao Tea Street in the city’s southwest. Top-quality leaves can run as high as 5,000 yuan per pound.

The 798 Art District is home to China’s red-hot modern art scene on an international scale; visit on a Saturday or Sunday when the area is filled with locals and visitors.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

EDUCATION WITHOUT YAWNS

Learning doesn’t have to boring! There are excellent ways to teach the kids a few things about history while they have a good time. You can’t miss with the Forbidden City, the largest surviving palace complex in the world. There are plenty of wide-open spaces here for kids to run amok in, so that while you’re appreciating the finest collection of imperial architecture in China, your little ones can imagine what it was like to have thousands of mandarins catering to their every whim. Sort of like having parents.

For museums, the Military Museum of the People’s Republic of China is a toy soldier-lover’s dream come true. It has endless collections of AK-47s, captured tanks, missile launchers, and other war toys. Your kids will love every minute of China’s 5,000-year military history. Easy access by subway ensures they won’t have to ask, “Are we there yet?” And the China Science & Technology Museum is a paradise for curious kids, this museum features hands-on interactive displays with a strong focus on Chinese inventions like the compass, gunpowder, and paper. The on-site “Fundazzle” playground will keep your little one entertained even when the robot performance is finished.

PERFORMANCES

Take the kids out to see amazing acrobats and they’ll see that hand-eye coordination doesn’t only come from playing video games. To really inspire, look for a performance featuring child acrobats who dedicate every day to perfecting their awe-inspiring craft. Another great entertainment option is the China Puppet Theater, where actors manipulate huge puppets through performances of Western classics like The Nutcracker and Chinese classics like The Monkey King. There’s a playground at the theater, too, for kids who just won’t sit still.

ACTIVITIES

China’s love affair with kites goes back nearly 3,000 years. Head for the open spaces of Tiananmen Square, Ditan Park, or the Temple of Heaven to fly a kite. Older folks with decades of flying experience will help send your child’s kite soaring into the air.

Kids love to climb, so climbing the Great Wall is a win-win. After climbing hundreds (or thousands) of steps, your little one will sleep soundly while dreaming of turning back the marauding Mongol hordes.

Head to Ritan Park (Altar of the Sun). Little tykes can ride the merry-go-round, older kids can try their luck on the climbing wall, and you can stop in for a drink at the outdoor Stone Boat, a particularly kid-friendly bar.

Who doesn’t love a boat ride? Cruise the imperial lakes at Houhai in a paddleboat, and take the family for a rectangular pie at Hutong Pizza when you get back to shore. In winter the lakes freeze over, and kids in ice chairs gleefully glide across the surface.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Although Beijing isn’t as inexpensive as it once was, it’s still a fabulous bargain compared to travel in Europe, North America, and more developed Asian nations such as Japan and South Korea. While expats have complained more and more of rising prices in the post-Olympics era, visitors from Western countries are often overwhelmed by a feeling that life in the city is practically free. Bottled water, snacks, subway and bus rides, or some steamed dumplings from a street stall, will all cost well under the equivalent of 50 cents. Average-length cab rides, a dish at a decent restaurant, or museum admission tickets will set you back only two or three dollars. And the capital is filled with acceptable hotels for about 50 bucks per night. Little is free in Beijing, but there’s also very little to make much of a dent in your wallet.

ART

The modern art scene in China has exploded onto the world stage over the past decade. Beijing’s 798 Art District, located northeast of the city center along the road to the airport, is the country’s artistic nucleus. The complex was built under East German supervision in the 1950s to house sprawling electronics factories, but artists took over after state subsidies dried up in the late 1990s. The district is now home to at least 100 top-notch galleries, and almost all of them are free.

OFFBEAT EXPERIENCES

Beijing’s urban sprawl is interrupted by a number of lovely parks designed in traditional Chinese style. Of particular historical significance are the four parks built around altars used for imperial sacrifice: the Altar of the Sun (Ritan), Altar of Heaven (Tiantan), Altar of the Earth (Ditan), and Altar of the Moon (Yuetan).

If you happen to be in Beijing for Spring Festival (Chinese New Year), you literally won’t be able to avoid the party atmosphere that overtakes the city. You may have seen a display of fireworks before, but have you ever been inside a fireworks show? It’s a good idea to bring earplugs, as the explosions go on at all hours for days on end.

CHEAP SIGHTSEEING

Don’t be afraid to hop on one of Beijing’s municipal buses and see where it takes you! Just remember the number of the line you took so you can get back to where you started—and grab a business card from your hotel just in case you get lost and need to flag down a taxi. Here’s a hint: bus lines with only one or two digits stay more or less within the city center, so you won’t have to worry about ending up in a farming village near Hebei.

Bus 4: Runs east-west along Chang’an Jie, the city’s main horizontal axis. Stops include the Military Museum, Xidan, Tiananmen Square, Wangfujing, and Jianguomen. Bus 5: Starts near the Di’anmen intersection south of the Drum and Bell towers and runs past Beihai Park and Tiananmen Square toward Qianmen (Front Gate). Bus 44: This loop line more or less follows the same route as Line 2 on the subway—a chance to travel along the path where the ancient city walls once stood, and you can get off at the same place you got on.

MUSEUMS

The city’s most famous museums aren’t exactly charging an arm and a leg for admission, and some ask only for donations or charge less than Y10.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Do I need any special documents to get into the country?

Aside from a passport that’s valid for at least six months after date of entry, and a valid visa, you don’t need anything else to enter the country. In theory, you’re required to have your passport with you at all times during your trip, but it’s safer to carry a photocopy and store your passport in a safe at your hotel (if they have one).

How difficult is it to travel around the city?

It’s extremely easy (traffic aside). Taxis are plentiful and cheap, and Beijing also has a good subway system that has expanded rapidly and now reaches more places. Stops are announced in both English and Chinese. Public buses can be a challenge because street signs are not often written in English and bus drivers are unlikely to be conversational in any foreign languages. Renting a car can be difficult and traffic and roads can be quite challenging, so driving on your own isn’t recommended. However, hiring a car and driver isn’t very expensive and is a good alternative for getting around. Beijing, with its many bike lanes, is a cycle lover’s city, so consider renting some wheels for part of your stay.

Should I consider a package tour?

If the thought of traveling unescorted to Beijing absolutely terrifies you, then sign up for a tour. But Beijing is such an easy place to get around in that there’s really no need. Discovery is a big part of the fun—exploring an ancient temple, walking down a narrow hutong or alleyway, stumbling upon a great craft shop or small restaurant—and that’s just not going to happen on a tour. If you’re more comfortable with a package tour, pick one with a specific focus, like a pedicab hutong ride or an afternoon of food shopping and cooking, so that you’re less likely to get a generic package.

Do I need a local guide?

Guides are really not necessary in a city like Beijing, where it’s easy to get around by taxi and public transportation, and where most of the important tourist destinations are easy to reach. An added plus is that the local people are friendly and always willing to give a hand. It’s much more gratifying to tell the folks back home that you discovered that wonderful backstreet or interesting restaurant all by yourself.

Will I have trouble if I don’t speak Chinese?

Not really. Most people in businesses catering to travelers speak at least a little English. If you encounter someone who doesn’t speak English, they’ll probably point you to a coworker who does. Even if you’re in a far-flung destination, locals will go out of their way to find somebody who speaks your language. Or you can make use of travel services such as Bespoke Beijing, which will arm you with a mobile phone, plus a stylish and personalized guide to the best sights, restaurants, bars, and nightlife, as well as access to a Chinese translator or English-speaking expert (www.bespoke-beijing.com).

Can I drink the water?

No, you can’t. All drinking water must be boiled. Bottled water is easily available all over the city and in outlying areas, such as the Great Wall. Most hotels provide two free bottles of drinking water each day. To be on the safe side, you may also want to avoid ice.

Are there any worries about the food?

China has suffered from some major national food scandals in recent years, from tainted milk to exploding watermelons, but there’s no need to be afraid in Beijing. Even the humblest roadside establishment is likely to be clean. If you have any doubts about a place, just move on to the next one. There’s no problem enjoying fruit or other local products sold from street stands, but any fruit that can’t be peeled should perhaps be cleaned with bottled water before eating.

Do I need to get any shots?

You probably don’t have to get any special vaccinations or take any serious medications if you’re not planning on venturing outside the capital. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warn that there’s some concern about malaria in some of the rural provinces much farther south of Beijing, such as Anhui, Yunnan, and Hainan. Immunizations for hepatitis A and B are recommended for all visitors to China.

Should I bring any medications?

It can be difficult to readily find some medications in Beijing, and while the city has several international clinics, prices for even over-the-counter remedies can be quite expensive. So make sure you have all your medications with you.

Can I use my ATM card?

Most ATMs in Beijing accept both MasterCard and Visa cards, but each bank may charge a different fee for each transaction. There are Citibank ATM machines located at several places around the city. Check the exchange rate before you use an ATM for the first time so that you know exactly how much local currency you want to withdraw.

Do most places take credit cards?

Almost all traveler-oriented businesses accept credit cards. You may encounter smaller restaurants and hotels that don’t accept them at all, but these are pretty rare. Some businesses don’t like to accept credit cards because their banks charge them exorbitant fees for credit-card transactions. They will usually relent and charge you a small fee for the privilege.

What if I don’t know how to use chopsticks?

Chopsticks are the utensils of choice, but cutlery is available in many restaurants. That said, it’s a good idea to brush up on your chopstick chops. The standard eating procedure is to hold the bowl close to your mouth and eat the food. Noisily slurping up soup and noodles is also the norm. It’s considered bad manners to point or play with your chopsticks, or to place them on top of your rice bowl when you’re finished eating (place the chopsticks horizontally on the table or plate). Don’t leave your chopsticks standing up in a bowl of rice—it makes them look like the two incense sticks burned at funerals, and is seriously frowned upon.

How should I dress?

Most Chinese people dress for comfort and you can do the same. There’s very little risk of offending people with your dress; Westerners tend to attract attention regardless of attire. Although miniskirts are best left at home, pretty much anything else goes.

Should I tip?

For a long time, tipping was officially forbidden by the government; as a result, locals simply don’t do it. In general, you can follow their lead without any qualms. Nevertheless, the practice is now beginning to catch on, especially among tour guides. You don’t need to tip in restaurants or in taxis.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Check out what remains of West’s 19th-century fingerhold in Beijing. The Old Legation Quarter, a walled area where foreign businesses and government offices were once housed, was heavily vandalized during the Cultural Revolution and altered again during the ‘80s boom. That said, a surprising number of early-20th-century European structures can still be found here.

Previous Map | Next Map | Beijing Maps

THE OLD LEGATION QUARTER

This walk begins on Dong Jiao Min Xiang. It can easily be reached via the lobby of the Novotel Xinqiao hotel. Exit through the back door right to the street. We’ll first take you down the north side of the street and then along its south side. The most prominent structure that remains of the quarter is St. Michael’s Catholic Church. Built by French Vincentian priests in 1902, this Gothic church is still crowded during Mass every Sunday.

FOREIGN EMISSARIES

The red building opposite the church started out as the Belgian Embassy and later became the Burmese (now Myanmar) Embassy following Burma’s liberation.

On the north side of the street at No. 15 is the former location of the French Legation. The former Cambodian leader Prince Sihanouk stayed here during his many visits to China. The old French Post Office is now a Sichuan restaurant. Hongdu Tailors (No. 28) was once tailor to the top Communist officials who came here to have their revolutionary Mao jackets custom-made.

At the northeast corner of Zhengyi Lu, the former Rue Meiji, is a grand-looking building that was once the Yokohama Specie Bank; peek in for a look at the early-20th-century interior and ceilings. The pleasant patch of greenery you see running down the center of Zhengyi Lu was created in 1925, when the old rice-transport canal was filled in with earth. Continue west on Dong Jiao Min Xiang. In the middle of the next block on your right are the gleaming headquarters of China’s Supreme People’s Court (27 Dong Jiao Min Xiang), which sits on the site of the former Russian Legation. A gate remains here from the original Russian complex.

FINANCIAL STREET

Walking up the south side of the street, you’ll see a building with thick Roman columns; this was first the Russia Asiatic Bank, and afterwards the National City Bank of New York—the fading letters NCB can still be seen in a concrete shield at the top of the building. This is now the Beijing Police Museum. Down a bit farther on the north side of the street, just before Tiananmen Square, is the old French Hospital. Opposite the hospital is the former American Legation (this is the last complex just before the steps leading to Tiananmen Square). It was rebuilt in 1901 after being destroyed by the Boxers. More than a century later, it has become home to some particularly high-end restaurants and retail spaces.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Most of China’s holidays and festivals are calculated according to the lunar calendar and can vary by as much as a few weeks from year to year. Check online for more specific dates.

Chinese New Year.

China’s most celebrated and important holiday, Chinese New Year follows the lunar calendar and falls between mid-January and mid-February. Also called Spring Festival (Chunjie), it gives the Chinese an official week-long holiday to visit their relatives, eat special meals, and set off firecrackers to celebrate the New Year and its respective Chinese zodiac animal. Students and teachers get up to four weeks off. Most offices and services reduce their hours or close altogether. WARNING: Avoid visiting during Spring Festival, as Beijing tends to shut down; many of the sights you’ll want to see may be closed.

Dragon Boat Festival.

The Dragon Boat Festival, on the fifth day of the fifth moon (usually in June), celebrates the national hero Qu Yuan, an honest politician who drowned himself during the Warring States Period of ancient China in despair over his inability to save his state (it was a time of great corruption). Legend has it that the fishermen who unsuccessfully attempted to rescue Qu by boat tried to distract fish from eating his body by throwing rice dumplings wrapped in bamboo leaves into the river. Today, crews in narrow dragon boats race to the beat of heavy drums, while balls of rice wrapped in bamboo leaves (zongzi) are consumed by the population en masse.

Labor Day.

Labor Day falls on May 1, and is another busy travel time. In 2008 the government reduced the length of this holiday from five days to two, but the length of the holiday now changes from year to year.

Mid-Autumn Festival.

Mid-Autumn Festival is celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth moon, which usually falls between mid-September and early October. The Chinese spend this time (trying to) gaze at the full moon and exchanging edible “mooncakes”: moon-shaped pastries filled with meat, red-bean paste, lotus paste, salted egg, or date paste, or other delicacies.

National Day.

Every October 1, China celebrates National Day, in honor of the founding of the People’s Republic of China back in 1949. Tiananmen Square fills up with a hefty crowd of visitors on this official holiday, with people granted the entire week off work and school. Domestic tourists from around the country flock to the capital during this time. Steer clear of Beijing during national week if you don’t want to battle endless crowds at all the main sights.

Qing Ming.

Not so much a holiday as a day of worship, Qing Ming (literally, “clean and bright”), or Tomb Sweeping Day, gathers relatives at the graves of the deceased on the 15th day from the spring equinox—April 4th, 5th, or 6th, depending on the year—to clean the surfaces and leave fresh flowers. In 1997 the staunchly atheist Communist party passed a law stating that cremation is compulsory in cities and other densely populated areas. Accordingly, this festival has since lost much of its original meaning.

Spring Lantern Festival.

The Spring Lantern Festival marks the end of the Chinese New Year, and is celebrated on the 15th day of the first lunar month (sometime in February or March, depending on the year). Residents flock to local parks for a display of Chinese lanterns and fireworks.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents