Fodor's The Complete Guide to African Safaris: with South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Namibia, Rwanda & the Seychelles (Full-color Travel Guide) (2015)

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

SEEING A LION

Lions. Are. Awesome. You probably already knew that. However, when it comes to seeing a lion on safari, forget all you know. We’re not talking about awesome lion facts that you may know, such as: A lion’s roar can be heard up to five miles away. Or, adult males can eat up to 88 pounds of meat in one sitting. We’re talking about how awesome it is to see big cats in their natural habitat. It’s an event every time. We’ve repeatedly seen veteran safari guides visibly humbled at the sight of lions. When you get close to a lion in the wild it’s an irreducible moment. You’re held in thrall, suspended in a world that consists of just you and one special animal, and this dimension simply does not exist in a zoo. The animal may be the same, but there’s an incomparable gravitas to seeing it in the environment in which it must struggle to survive. View a lion on safari, and on an unconscious level you’ll process not only its marvelous appearance, but also its dramatic relationship to its surroundings. You may happen on a pride sleeping under the shade of an acacia tree and be overcome by how endearing the scene is. But you also understand that you’re witnessing more than a lazy afternoon nap. On an unspoken level you just know that the slumbering cats are storing their energy for an epic hunt. Or, as you watch a group of lionesses intently stalking through tall grass, you might even feel the urgency of their primal hunger. And don’t even get us started on leopards.

NOT SEEING A LION

As breathtaking as it is to see a lion on safari, spotting them shouldn’t be a single-minded pursuit. If you’re preoccupied with seeing a big cat, or other Big Five animals, every time you set out on a game drive, you may unintentionally miscalculate the success rate of your journey. When asked about their drives, people often say, “It was great! We saw four lions and two cheetahs!” Or, “It was good, but we didn’t see any rhino or leopards.” This kind of scorekeeping fails to account for the numerous sightings that can be equally wondrous. Often when lions are found, your driver will cut the engine so that you can silently behold their splendor. We highly recommend that you direct this kind of undivided attention to other, more “common” sights throughout your drive as well. Ask your driver to cut the engine at random intervals. Then sit stock still and observe the open plain. Feel it teeming with life. Listen to it. You’ve never quite “heard” silence like the quiet of the savanna. The landscape is playful—watch the “Kenya Express,” an affectionate term for the famously skittish warthogs throughout Kenya, who comically dash with their tails up like antennas at the slightest disturbance. The landscape can be poignant—witness the heart-wrenching vulnerability of a baby giraffe that has strayed too far from its mother. The landscape can be stoic; see shaggy waterbuck, relatively fearless because lions rarely prey on them, blithely lounging in the grass, staring at you with practiced indifference. But most of all, the landscape is a wonderland with the subtle interplay of wildlife happening everywhere. Receive all it has to offer and you’ll be well rewarded.

GETTING THE PERFECT SHOT

Three graceful giraffes, dwarfed by towering Mt. Kilimanjaro, bathed by the orange glow of the setting sun, are surveying the plains. Suddenly, all three at once turn to look straight at you, practically mugging for the camera, and click. You got it. An image you’ll cherish, a picture worth a thousand words and 8,000 miles of travel. Sure there are tons of professional images of African wildlife that put your lucky shot to shame. But this is your special moment; you own it, and there’s a particular pride that comes with every image you capture. Your pictures document your trip through a highly personal lens, both photographically and existentially. Perhaps this is why the exact same scene captured with superior shutter speed and composition doesn’t inspire nearly as strong a reaction. When you get your “perfect” shot, there’s a personal poetry to it that can’t be duplicated by anybody else’s camera. Your pictures tell your story.

NOT GETTING THE PERFECT SHOT

The problem with the perfect shot is the amount of time you can spend viewing your surroundings through a 2.7-inch LCD screen to get it. Although you may never have another chance to photograph the gaping maw of a giant hippo as he suddenly rises from the river, you may also never get another chance to experience that moment. Too often folks on safari witness spectacles unfold not before their very eyes (or even through binoculars), but through a tiny screen—waiting for fauna to fall into place, waiting to capture the best action shot. It’s somewhat disorienting to consider that you can be in Africa (Africa!), alternating your gaze between the digital image you’re trying to capture and the one that you just took. The splendid rise of a hot-air balloon over the sand dunes of Namibia or the impressive leaps of Masai warriors are singularly unique events that shouldn’t be witnessed solely through a single-lens reflex. Before you know it, your firsthand experiences will seem nebulous and your memories prematurely dim, leaving you with a succession of moments that can only be recalled through photos and video. Set up your shots, take lots of pictures; they’re precious. But more precious is the primary, full-sensory, romantic experience that can only be achieved by unencumbered, full engagement with your surroundings.

GOING ON A SUNDOWNER

A lot of the recommendations above are variations on “be in the moment”—based on the notion that because safaris are exhilarating adventures with a raft of stimuli, it sometimes takes a concentrated effort to drink in the here-and-now. Well, quite literally, there’s nothing like a sundowner to help you drink it all in. The recipe is simple: Take one particularly scenic spot, often with vistas that span country borders and stretch to distant mountains, add your choice of cocktails, and watch the sun drench what seems like half of Africa in various hues of orange and pink. Most luxury and semi-luxury camps offer this supernal show, and it shouldn’t be missed. They often set you up with director’s chairs, which is appropriate, because it’s here, in the fading light, as tranquility envelopes the land, that you feel in charge—fully recharged. Raise a glass and toast your glorious day—“kwahafya njema!”—as the African sun makes its graceful exit.

NOT GOING ON A SUNDOWNER

Just kidding. You should go.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

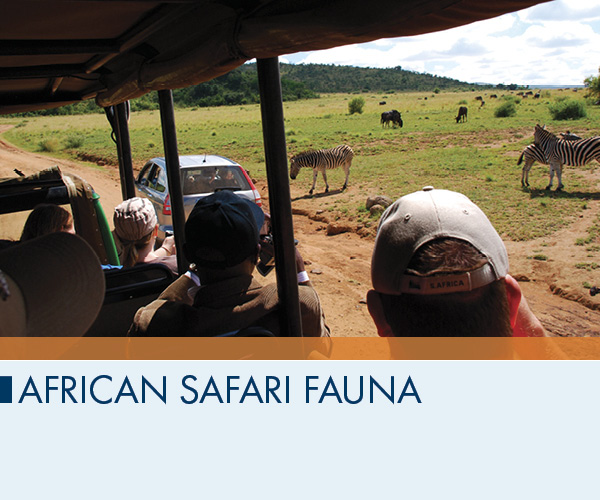

The fauna that can be found on an African safari is as varied and vast as the continent’s landscape. Africa has more large animals than anywhere else in the world and is the only place on earth where vast herds still roam the plains.

The Big Five was originally a hunting term referring to those animals that posed the greatest risk to hunters on foot—buffalo, elephant, leopard, lion, and rhino. Today it has become one of the most important criteria used in evaluating a lodge or reserve, though it should never be your only criterion.

THE AFRICAN BUFFALO

Often referred to as the Cape buffalo, this is considered by many to be the most dangerous of the Big Five because of its unpredictability and speed. Do not confuse it with the docile Asian water buffalo as the Cape buffalo is a more powerful and untameable beast with a massive build and short strong legs. They have few predators other than human hunters and lions. It generally takes an entire lion pride to bring down an adult buffalo, although calves, weak and sick adults can be taken by wild dog and spotted hyena. Lions risk being mobbed by the herd when they do attack, and are sometimes trampled and gored.

THE ELEPHANT

The largest of the land animals, it once roamed the continent by the millions. Today, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the population, mainly found in Southern and Eastern Africa, is between 470,000 and 600,000. The continent’s forest elephants (of central and West Africa) are still under severe threat.

THE RHINO

There are two species of these massive primeval-looking animals in Africa: the black, or hook-lipped rhino, and the white, or square-lipped rhino. Both species have poor eyesight but excellent hearing, and because of their erratic tempers, they may sometimes charge without apparent reason.

THE LION

Known as the king of beasts—the Swahili word for lion, “simba,” also means “king,” “strong,” and “aggressive”—this proud animal was once found throughout the world. Today, the majority of the estimated 23,000 lions are found in sub-Saharan Africa— a small population are also found in India—in grasslands, savannah, and dense bush.

THE LEOPARD

Secretive, stealthy and shrewd, the leopard is the most successful predator of all Africa’s big cats. They are often difficult to spot on safari, primarily because they are nocturnal, but if you go on a night game drive your chances will increase tremendously. South Africa’s Sabi Sands area has the highest density of leopards in the world and you would be very unlucky not to see one there.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Birds | Other Animals

BIRDS

Many people come to Africa solely for the birds. There are thousands of winged beauties to ooh and aah over; we mention a few to look out for.

BATELEUR EAGLE

This spectacular bird, which looks as if it’s “balancing” in the air, is found throughout sub-Saharan Africa and is probably one of the best known birds in Africa. Mainly black with a red back, legs, and beak and white underneath its wings, the Bateleur eagle can fly up to 322 km (200 miles) at a time in search of prey, which includes antelope, mice, other birds, snakes, and carrion. They mate for life, often using the same nest for several years.

LAPPET-FACED VULTURE

The largest and most dominant of the vultures, this scavenger feeds mainly on carrion and carcasses that have been killed by other animals. The most aggressive of the African vultures, it will also, on occasion, kill other weaker birds or attack the nests of young birds as prey. The Lappet-faced vulture has a bald head and is pink in color with a wingspan of up to 8½ feet.

LILACBREASTED ROLLER

This stunning-looking bird with a blue-and-lilac-colored breast is found in the open woodland and savanna plains throughout sub-Saharan Africa. It’s usually solo or in pairs sitting in bushes or trees. Both parents nurture the nest and are extremely territorial and aggressive when it comes to defending it. During mating, the male flies up high and then rolls over and over as it descends, making screeching cries.

KORI BUSTARD

One of the world’s heaviest flying birds is found all over Southern and East Africa. Reaching almost 30 pounds and about 3½ feet in length, the male is much larger than the female but both are gray in color, have crests, and gray-and-white necks. Although it does fly, the majority of its time is spent on land where it can find insects, lizards, snakes, and seeds. One male mates with several females, which then raise the young on their own.

PEL’S FISHING OWL

A large, monogamous, ginger-brown owl with no ears, bare legs, and dark eyes, it lives along the banks of rivers in Kruger Park, South Africa’s Kwa-Zulu Natal province, Botswana’s Okavango Delta, and Zimbabwe. One of only three fishing owls in the world, it hunts at night with its sharp talons and dozes in tall trees during the day. The owls communicate with each other through synchronized hooting at night as they guard their stretch of riverbank.

WATTLED CRANE

The rarest African crane is found in Ethiopia, Zambia, Botswana, Mozambique, and South Africa. A gray-and-white bird, it can reach up to 5 feet tall and, while mating, will nest in pairs along the shallow wetlands of large rivers. They’re omnivorous and sometimes wander onto farmlands where they’re vulnerable to poisoning by farmers. They occur in pairs or sometimes in large flocks, especially in the Okavango Delta. The crane is on South Africa’s critically endangered list.

OTHER ANIMALS

You’ll be amazed by how many visitors ignore a gorgeous animal that doesn’t “rank” in the Big Five or lose interest in a species once they’ve checked it off their list. After you’ve spent a few days in the bush, you’ll hopefully understand the idiocy of racing about in search of five animals when there are 150 equally fascinating species all around you. Here are a few to look out for.

BABOONS

These are the most adaptable of the ground-dwelling primates and can live in all manner of habitats as long as they have water and a safe place to sleep. Baboons travel in groups of up to 40 animals, sleeping, eating, and socializing together. Although they’re hugely entertaining to watch, always keep your vehicle windows rolled up. Like other animals, they can be vicious when they feel threatened, and they have huge canine teeth. They eat mainly plants, but will also consume small quantities of meat.

CHEETAH

Reaching speeds of 70 mph, cheetahs are the world’s fastest land animals—they have slender, muscular legs and special pads on their feet for traction. With its characteristic dark spots, the cheetah also has a distinctive black “tear” line running from the inside corner of its eye to the mouth. A solitary, timid creature, cheetahs are found mainly in open savanna. Males and females can sometimes be seen together after mating, but usually one or two males—often brothers—are alone and females are with the cubs. Cheetahs generally prey on gazelles and impalas. Sadly, this stunning cat is one of the most endangered animals, due to shrinking habitat, loss of prey, and disease.

GIRAFFE

The biggest ruminant and tallest living animal, giraffes are social creatures that live in loose herds that can spread out over half a mile. Although there are no leaders, the males fight over females using a “necking” technique, winding their necks around each other, pushing and shoving. Giraffes either walk or gallop and are ubiquitous in most national parks. It’s easy to tell the difference between males and females. The tops of the male’s horns are bare and shiny from fighting; the females have bushy tips like paintbrushes.

HIPPO

Though they may be comical looking, these are actually one of Africa’s most dangerous animals. The most common threat display is the yawn, which is telling you to back off. Most guides will give them a wide berth. Never get between a hippo and its water, as this will appear to them that you’re trying to corner them and may result in an attack. The comical nighttime sounds of hippos snorting and chortling will be one of your safari’s most memorable experiences.

IMPALA

One of the most populous animals in the African bush, impalas can be found in grasslands and wooded areas, usually near water. Similar in appearance to a deer, these one-of-a-kind antelopes are reddish-brown with white and black markings. A typical herd has one dominant male ruling over his harem, although bachelor herds are usually in the vicinity, with hopeful individuals awaiting their turn to oust the ruling male. It’s a hugely successful animal because it’s both a grazer and a browser.

AFRICAN WILD DOGS

Also called the “painted dog” or “painted wolf” because of each uniquely spotted coat, the wild dog is headed toward extinction with numbers of approximately 3,000 to 5,000 and shrinking. This highly social animal with batlike ears and a furry tail lives in small packs of about 15; only the alpha male and female are allowed to breed. Intelligent and quick, wild dogs hunt as a coordinated pack running down their prey, which varies from antelopes to zebras, until exhausted. They have an amazingly successful catch rate of 85%. They breed in underground dens, often those abandoned by warthogs.

BUSH BABY

These small nocturnal primates, which make cries similar to that of a human baby, range in size from 2 ounces to 3 pounds. During the day, they stay in tree hollows and nests, but at night you’ll see them leaping and bouncing from tree to tree in pursuit of night-flying insects. Their main predators are some of the larger carnivores, genets, and snakes.

HYENA

Hyenas live in groups called clans and make their homes in dens. They mark their territory with gland secretions or droppings. Cubs are nursed for about 18 months, at which point they head out on hunting and scavenging sprees with their mothers. Both strategic hunters and opportunists, hyenas will feed on their own kill as well as that of others. Aggressive and dangerous, African folklore links the hyena with witchcraft and legends.

NILE CROCODILE

Averaging about 16 feet and 700 pounds, this croc can be found in sub-Saharan Africa, the Nile River, and Madagascar. They eat mainly fish but will eat almost anything, including a baby hippo or a human. Although fearsome looking and lightning quick in their attack, they’re unusually sensitive with their young, carefully guarding their nests until their babies hatch. Their numbers have been slashed by poachers, who seek their skins for shoemakers.

SPRINGBOK

This cinnamon-color antelope has a dark brown stripe on its flanks, a white underside, and short, slender horns. It often engages in a mysterious activity known as “pronking,” a seemingly sudden spurt of high jumps into the air with its back bowed. Breeding takes place twice a year, and the young will stay with their mothers for about four months. These herbivores travel in herds that usually include a few territorial males.

WILDEBEEST

This ubiquitous herbivore is an odd-looking creature: large head and front end, curved horns, and slender body and rear. Often called “the clowns of the veld” they toss their heads as they run and kick up their back legs. Mothers give birth to their young in the middle of the herd, and calves can stand and run within three minutes and keep up with the herd after two days.

ZEBRA

Africa has three species: the Burchell’s or common zebra, East Africa’s Grevy’s zebra (named after former French president Jules Grevy), and the mountain zebra of South and Southwestern Africa. All have striped coats and strong teeth for chewing grass and often travel in large herds. A mother keeps its foal close for the first few hours after birth so it can remember her stripes and not get lost. Bold and courageous, a male zebra can break an attacking lion’s jaw with one powerful kick.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

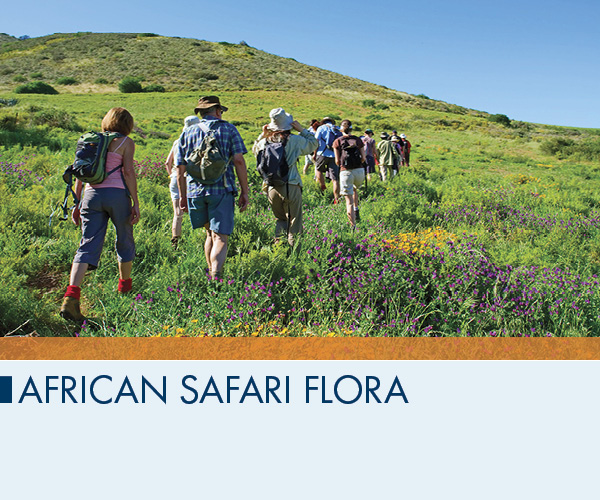

Trees | Plants

Although the mammals and birds of Africa are spectacular, we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention the amazing plant life of this varied landscape. The floral wealth of the African continent is astounding, with unique, endemic species growing in all parts—the South African Cape has one of the richest of the world’s six floral kingdoms. There are also several species of non-native plants and trees in Africa that have become the subject of lively environmental debates due to their effect on the environment.

TREES

AFRICAN MAHOGANY

Originally from West Africa, you’ll find this majestic tree in warm humid climates like riverine forests; you’ll also find them in the Florida everglades. A member of the Khaya genus, the mahogany requires significant rainfall in order to thrive and can reach up to 140 feet with a 6-foot trunk diameter. Its much-prized, strong, richly colored wood is sought after for furniture making and boat building.

BAOBAB

A huge, deciduous quirky-looking tree that grows throughout mainland Africa, the baobab has a round, hollow trunk with spiny-looking branches growing out at the top in all directions—it almost looks like it’s upside down with the roots sprouting out at the top. Known for storing water in its trunk, the baobab lives in dry regions and can live up to 400 years; some have lived for more than 1,000 years. The hollow trunks have been home to a prison and a post office.

FEVER

The fabled fever tree, which thrives in damp, swampy habitats throughout sub-Saharan Africa, has a luminous, yellow-green bark that’s smooth and flaky, and its branches have white thorns and clusters of yellow flowers. It’s so-named because before mosquitoes were known to carry malaria, travelers often contracted the disease where fever trees grew and thus they were wrongly thought to transmit malaria. Bees are attracted by the sweet smell of the flowers, and birds often nest in its branches as the thorns offer extra protection against predators.

FIG

There are as many as 50 species of fig trees in Southern and East Africa, where they may reach almost gigantic proportions, growing wherever water is nearby. Although figs provide nourishment for a variety of birds, bats, and other animals, they’re most noted for their symbiotic relationship with wasps, which pollinate the fig flowers while reproducing. The fig seed is dispersed throughout the bush in the droppings of animals who feed on the rich, juicy fruit.

JACKALBERRY

The large, graceful jackalberry, also known as the African ebony, is a riverine tree found all over sub-Saharan Africa. It can grow up to 80 feet tall and 16 feet wide. It bears fragrant white flowers and a fleshy yellow fruit that jackals, monkeys, baboons, and fruit-eating birds love. Its bark and leaves are used in traditional medicine with proven pharmacological benefits.

SAUSAGE

This unique tree, found in Southern Africa, bears sausagelike fruit that hangs from ropelike stalks. The tree grows to be about 40 feet with fragrant red flowers that bloom at night and are pollinated by bats, insects, and the occasional bird. The fresh fruit, which can grow up to 2 feet long and weigh as much as 15 pounds, is poisonous but can be made into various medicines and an alcohol similar to beer.

PLANTS

MAGIC GUARRI

This round shrub grows along floodplains and rivers. It has dark green leaves and white or cream-color flowers, and its fruit is fleshy and purple with a seed in its center. The fruit can be fermented to produce an alcoholic beverage, and the bark is used as a dye in basket making. The twigs have been used as toothbrushes, while the root can be used as mouthwash. The wood, sometimes used to make furniture, is said to have magical or supernatural powers and is never burned as firewood.

STRELITZIA FLOWER

Also known as Bird of Paradise or the crane flower, the strelitzia is indigenous to South Africa. It grows up to 6½ feet tall with a beautiful fan-shape crown with bright orange and bluish-purple petals that grow perpendicular to the stem, giving it the appearance of a graceful bird.

WELWITSCHIA MIRABILIS

With its long, wide leathery leaves creeping over the ground, this somewhat surreal-looking plant is also one of the world’s oldest plants; it’s estimated that welwitschia live to about 1,500 years, though botanists believe some can live to be 2,000 years old. It’s found in the Namib Desert and consists solely of two leaves, a stem base, and roots. The plant’s two permanent leaves lie on the ground getting tattered and torn, but grow longer and longer each summer.

WILD THYME

Also called creeping thyme, wild thyme grows mainly in rocky soil and outcrops. Its fragrant flowers are purple or white, and its leaves are used to make herbal tea. Honeybees use the plant as an important source of nectar. There’s also a species of butterfly whose diet consists solely of wild thyme.

CAPE FYNBOS

There are six plant kingdoms—an area with a relatively uniform plant population—in the world. The smallest, known as the Cape Floral Kingdom or Capensis, is found in South Africa’s southwestern and southern Cape; it’s roughly the size of Portugal or Indiana and is made up of eight different protected areas. In 2004 it became the sixth South African site to be added to the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Fynbos, a term given to the collection of plants found in the Cape, accounts for four-fifths of the Cape Floral Kingdom; the term has been around since the Dutch first settled here in the 1600s. It includes no less than 8,600 plant species including shrubs, proteas, bulbous plants like gladiolus and lachenalias (in the hydrangea family), aloes, and grasslike flowering plants. Table Mountain alone hosts approximately 1,500 species of plants and 69 protea species—there are 112 protea species worldwide.

From a distance, fynbos may just look like random clusters of sharp growth that cover the mountainous regions of the Cape, but up close you’ll see the beauty and diversity of this colorful growth. Many of the bright blooms in gardens in the U.S. and Europe, such as daisies, gladioli, lilies, and irises, come from indigenous Cape plants.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents