Football For Dummies (2015)

Part II

Go, Offense!

Chapter 7

The Offensive Line at Work in the Trenches

In This Chapter

![]() Surveying the center’s (and everyone else’s) duties

Surveying the center’s (and everyone else’s) duties

![]() Examining lineman body types

Examining lineman body types

![]() Getting to know the keys to good line play

Getting to know the keys to good line play

![]() Understanding blocking, holding, and other things that linemen do

Understanding blocking, holding, and other things that linemen do

Football isn’t a relationship-driven business. If any positions could be used to illustrate that point, they would be the offensive and defensive line. The offensive and defensive lines are the sharks and the dolphins, the mongooses and the cobras, of football. In other words, they’re natural enemies. Being a defensive lineman, I never encouraged friendships with offensive linemen, but I always respected them. My job was to beat and overpower them in order to help my team win.

When I was with the Raiders in the 1980s, two opposing offensive linemen stuck out: Anthony Muñoz, a tackle with the Cincinnati Bengals, and Dwight Stephenson, the Miami Dolphins’ center. Unlike many offensive linemen, both of these men were very athletic in addition to being rugged and physical. That’s the ideal combination for this position. I’ve seen Muñoz play basketball, and for a 280-pounder, he moved as if he were 100 pounds lighter. Great feet. When the ball was snapped, I wanted to be quicker than the man blocking me. My plan was to beat him off the ball and get by him before he could react.

When I was with the Raiders in the 1980s, two opposing offensive linemen stuck out: Anthony Muñoz, a tackle with the Cincinnati Bengals, and Dwight Stephenson, the Miami Dolphins’ center. Unlike many offensive linemen, both of these men were very athletic in addition to being rugged and physical. That’s the ideal combination for this position. I’ve seen Muñoz play basketball, and for a 280-pounder, he moved as if he were 100 pounds lighter. Great feet. When the ball was snapped, I wanted to be quicker than the man blocking me. My plan was to beat him off the ball and get by him before he could react.

The job of offensive linemen? To protect the most hunted commodity in the game — the quarterback — and to block for the ball carrier. The line also opens up holes in the defense for the running backs (by blocking, or impeding the movement of, defenders). Ball carriers try to go through these holes, which are also called running lanes. The ability to run effectively in a football game is the end result of the offensive line winning the war at the line of scrimmage. It’s man against man, and whoever wants it more usually wins.

The offensive line is also essential to the passing game. Its job is to shield the quarterback, allowing him two or three seconds of freedom in which to throw the ball. The more time the line gives the quarterback to scan the field and find an open receiver, the better chance the quarterback has of a completion or a touchdown pass. Without the offensive line (or O line), the offense would never get anywhere.

This group, more than any other, needs to work together like the fingers on a hand. The linemen want their offensive teammates to gain yards — the more the merrier. You’ll notice that when a team has a great running back who’s gaining a lot of yards, the offensive line is usually mentioned as doing its job.

In this chapter, I explain the positions that make up the offensive line, give some insight into the personalities of offensive linemen, and cover some of the techniques that offensive linemen use to block for the quarterback and running backs.

Looking Down the Line

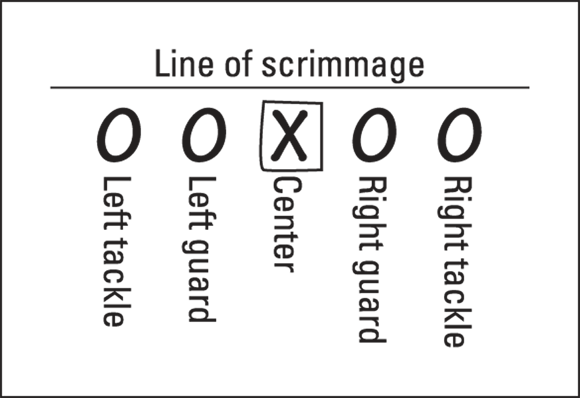

The offensive line is made up of five players, with the man in the middle called the center. Every offensive line position is based on the center. To the right of him is the right guard, and outside the right guard is the right tackle. To the left of the center is the left guard, and outside the left guard is the left tackle. Figure 7-1 helps you see the positioning of the offensive line’s personnel.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 7-1: The personnel on the offensive line.

If the quarterback is right-handed, the left tackle is also referred to as the blind-side tackle. Why? Well, a right-handed quarterback generally drops back to pass and turns his head to the right while doing so. He can’t see behind him, so his left side is his blind side.

The following sections give some generalities about the players at the three main offensive line positions — center, guard, and tackle.

The most special offensive lineman: The blind-side tackle

Most coaches put their best athlete at left tackle if their quarterback is right-handed (and more than 90 percent are). Ideally this player has quick feet and a good sense of balance.

The blind-side tackle doesn’t have to be the biggest, baddest player on the team; he can weigh 300 pounds and be quite adequate. But reach (arm length) is important, and knowing how to use your arms and hands to block or jam (place your hands on the top of your opponent’s jersey number) is critical. Getting his hands on the defensive player’s numbers, so to speak, guarantees that the lineman is keeping a distance between himself and the defensive player. Gaining this advantage is imperative.

By maintaining proper distance, the offensive lineman isn’t as susceptible to the defensive lineman’s techniques and moves. If he keeps that distance, he has more time to get his feet into position to block the defender on each move. Also, distance gives the lineman time to adjust laterally and get in front of his man. If the defender is body to body or hip to hip with the offensive lineman, the lineman is beaten because the defensive player can grab him. The closer the defensive player gets to you, the harder it is to recover and get the correct positional leverage on him.

In his 2006 book The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game (W.W. Norton & Company), author Michael Lewis described why the blind-side tackle became such an important position and how blind-side tackle Michael Oher rose from poverty with the help of friends and family to become a promising football player. The Blind Side was made into a movie in 2009 starring Sandra Bullock as the wealthy society lady who adopted Oher. I highly recommend the book and the movie, and not just to football fans. Oher’s story is heartwarming and gives a good glimpse into the inner workings of football.

Centers

Like a center in basketball, a football center is in the middle of the action. He’s the player who snaps (or delivers) the ball to the quarterback. As the snapper, he must know the signal count — when the quarterback wants the ball to be snapped, indicated by a series of commands, such as “Down. Set. Hut hut hut!”

This center-quarterback exchange initiates every offensive play. Before the play begins, the center stands over the ball and then bends down, usually placing both hands around the front tip of the football. He snaps (or hikes) the ball between his legs to the quarterback. (Refer to Chapter 4 for an illustration of the snap.)

This center-quarterback exchange initiates every offensive play. Before the play begins, the center stands over the ball and then bends down, usually placing both hands around the front tip of the football. He snaps (or hikes) the ball between his legs to the quarterback. (Refer to Chapter 4 for an illustration of the snap.)

The exchange of the football is supposed to be a simple action, but occasionally it gets bungled, resulting in a fumble. A fumble can be caused by the center not snapping the ball directly into the quarterback’s hands (perhaps because he’s worried about being hit) or by the quarterback withdrawing his hands before the ball arrives. Because hands are essential to good blocking, centers sometimes worry more about getting their hands into position to block than cleanly snapping the ball to the quarterback. Coaches refer to those poor snaps as short-arming the ball. In other words, the center doesn’t bring the ball all the way back to the quarterback’s hands.

In addition to delivering the ball cleanly to the quarterback, a center must know the blocking responsibilities of every other offensive lineman. The offense never knows beforehand how the defense will set up. And unlike the offense, the defense may move before the ball is snapped, which allows a defense to set up in a vast array of formations. The center is essentially a coach on the field, redirecting his offensive line teammates as necessary based on how the defense aligns itself. On nearly every play, the center points to the defenders and, using terminology that the defense can’t decipher, gives his fellow linemen their blocking assignments.

Centers tend to be quick, smart, and even-keeled. The other linemen look to the center for leadership and stability. In addition to being mentally tough, a center needs to be physically tough so he can absorb hits from defensive players while he’s concentrating on cleanly delivering the football to the quarterback.

Centers tend to be quick, smart, and even-keeled. The other linemen look to the center for leadership and stability. In addition to being mentally tough, a center needs to be physically tough so he can absorb hits from defensive players while he’s concentrating on cleanly delivering the football to the quarterback.

Guards

Guards, who line up on either side of the center, should be some of the best blockers. In a block, an offensive lineman makes contact with a defensive player and uses his hands, arms, and shoulders to move him out of the way. A guard is doing his job if he clears the way, creating a hole for a running back to run through. A guard also must be able to fight off his man — stopping the defender’s forward momentum — and prevent him from rushing the quarterback on a pass play.

The neutral zone

The neutral zone is the area between the offensive and defensive lines. It’s the length of the ball in width. Only the center is allowed in the neutral zone until he snaps the ball. If a lineman from either team lines up in this zone prior to the snap of the ball, his team incurs a 5-yard penalty.

Tackles

Tackles tend to be the biggest linemen, and in the NFL they’re generally the most athletic. (Figure 7-2 shows one of the NFL’s best tackles, Ryan Clady of the Denver Broncos.) Tackles should be the stars of the offensive line because their job on the ends of the line is to repel some of the game’s best defensive linemen and pass-rushers. They need to have great agility and the strength necessary to seal off the outside when a running play occurs. (Sealing off the outside means preventing the defensive players from reaching the corner of the line and tackling the ball carrier.)

Photo credit: © Paul Jasienski/Getty Images

Figure 7-2: Ryan Clady of the Denver Broncos is one of the premier offensive tackles in the NFL.

Sometimes a tackle must shove a defensive player outside when the play is designed to go toward the middle of the field. He has a lot of responsibility on the edge (the outside shoulder of the defensive end or linebacker aligned over him) because, if the tackle succeeds in containing the defensive players, the ball carrier has an open field in which to run. Sometimes the tackle must block his man toward the inside, thus allowing the ball carrier to run wide and outside the edge. In some plays, a tackle blocks down on the defensive tackle while the guard pulls to block the defender aligned over the tackle, moving that defender away from the running lane.

Not all running plays are designed to go inside the tackles. Off-tackle runs are usually run to the strong side of the formation, where the tight end, who serves as another blocker, lines up. On off-tackle runs, the tackle must contain his man and push him inside toward the center of the line as the ball carrier runs wide, or outside the tackle. If the tackle can’t move his man, he must prevent this defensive end or linebacker from reaching the edge of the line of scrimmage, shielding the ball carrier from the defensive pursuit.

Not all running plays are designed to go inside the tackles. Off-tackle runs are usually run to the strong side of the formation, where the tight end, who serves as another blocker, lines up. On off-tackle runs, the tackle must contain his man and push him inside toward the center of the line as the ball carrier runs wide, or outside the tackle. If the tackle can’t move his man, he must prevent this defensive end or linebacker from reaching the edge of the line of scrimmage, shielding the ball carrier from the defensive pursuit.

The Lineman Physique: Fat Guys Doing the Job

Fans often look at offensive linemen and say that they’re out of shape because they have big, round bodies. But that’s the kind of physique most offensive line coaches look for. They don’t want sculpted bodies; they want bulky players like Bill Bain, who played for the Los Angeles Rams in the 1980s, and Cleveland Browns tackle Joe Thomas. These players have great body mass and great natural strength. If you’ve been carrying 300+ pounds around most of your life, you tend to develop good leg strength and a powerful torso. If you’re a big man, though, you must have quick feet and good athletic ability to play on the offensive line — that way you can move the weight and move people out of the way. That’s what Thomas has.

The perception used to be that you should stick the biggest, least athletic men on the offensive line, but today’s offensive linemen have gone a long way toward shattering that notion. Players like Joe Thomas, Joe Staley, and Ryan Clady range in size from 310 to 325 pounds, and they’re fast, agile, and mean.

Today, offensive linemen fall in two categories:

· The big, burly (heavyset) lineman: During the Cowboys’ Super Bowl run from 1992 to 1995, when Emmitt Smith was the best runner in pro football, the Dallas line consisted of this type of lineman. These players imposed their will on their opponents and pounded them repeatedly — considered a power offense. Their style was to beat their opponents into submission. They limited their running plays to maybe five or six; they had those plays and stuck with them.

The power offense is common when a coach believes that his offensive line is bigger and stronger than the opposition’s defensive line. The Cleveland Browns had such an offensive line for Jim Brown. The problem defensive players face against such a powerfully built line isn’t the first running play, or the second running play, but the ninth play and beyond. As a defensive player, you get tired of 300-pound guys hammering at your head.

· The smaller, quicker lineman: This type of lineman is light and agile, with the ability to run and block on every play (they call that pulling). This lineman takes more of a surgical approach, slicing and picking the defense apart. The best example of this type of line play is the classic West Coast offense. This scheme involves a lot of angle blocking, which means an offensive lineman rarely blocks the defensive player directly in front of him; he does everything in angles.

The San Francisco 49ers used this finesse offense exclusively while winning four championships in the 1980s. The Denver Broncos won Super Bowl XXXII and XXXIII in 1998 and 1999 with what’s considered by today’s standards to be a small offensive line, with an average size of 290 pounds. The Broncos used a variation of the West Coast offense, which their head coach, Mike Shanahan, incorporated into his offense after serving as the 49ers’ offensive coordinator for three seasons.

I see the difference between these two offensive line styles as the difference between heavyweight boxers George Foreman and Muhammad Ali, with the West Coast style being Ali and the power offense style being Foreman. Every one of Foreman’s body punches is magnified by ten — all brute force — whereas Ali works you over like a surgeon, slicing and picking you apart.

I see the difference between these two offensive line styles as the difference between heavyweight boxers George Foreman and Muhammad Ali, with the West Coast style being Ali and the power offense style being Foreman. Every one of Foreman’s body punches is magnified by ten — all brute force — whereas Ali works you over like a surgeon, slicing and picking you apart.

What style a team chooses often depends on its quarterback, the size and ability of its offensive linemen, and the coach’s offensive preference. If your quarterback has the ability to escape the rush, the West Coast finesse works fine. If you have an immobile quarterback, you may want Foreman-like blockers who are difficult to get past.

What style a team chooses often depends on its quarterback, the size and ability of its offensive linemen, and the coach’s offensive preference. If your quarterback has the ability to escape the rush, the West Coast finesse works fine. If you have an immobile quarterback, you may want Foreman-like blockers who are difficult to get past.

Understanding the Keys to Successful Offensive Line Play

Because the offensive line’s job is so important, linemen need to develop certain characteristics, both individually and as a unit. The sections that follow outline some of those critical traits.

The proper stance

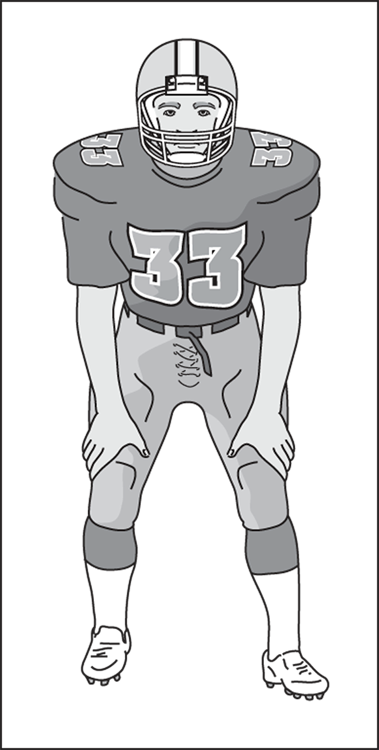

Offensive linemen often use a two-point, or up, stance, especially if the team plans to pass. The best two-point stance for a lineman is to be balanced, meaning that the right foot isn’t way back. When the foot is back too far, the lineman has a tendency to turn a little more. A lineman must not turn his body to the outside or to the interior. If he gets caught leaning to the outside, he could give the defensive player the corner (the outside edge). When a lineman gives the defensive player the corner, the defender simply dips his shoulders and then runs forward to that corner. Figure 7-3 shows the proper two-point stance for an offensive lineman.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 7-3: An offensive lineman’s two-point stance ensures that he remains balanced.

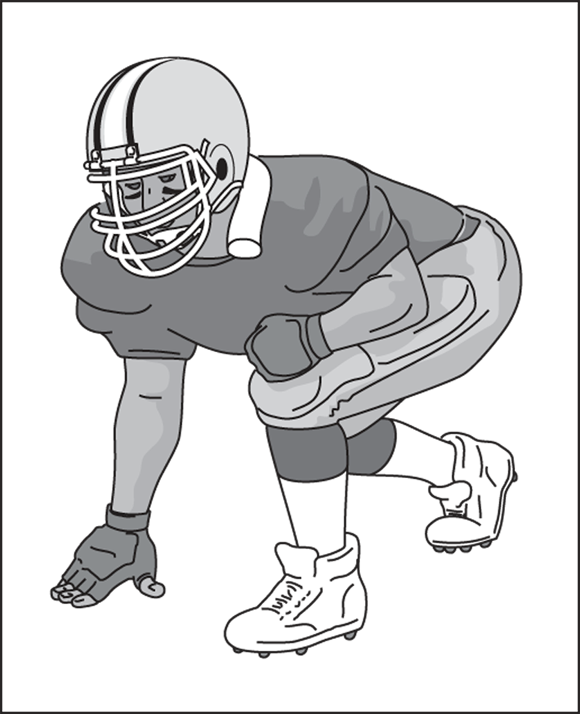

On normal downs in which the offense may opt to run or pass the football, many teams put their linemen in a three-point stance, which means right hand on the ground and right foot back, as shown in Figure 7-4 . A player must get comfortable in this stance and also maintain his balance so that he doesn’t telegraph what he intends to do. The hand on the ground shouldn’t be too far forward as to cause a dip in the shoulders; those should be square. From that stance, you can pull to the right, pull to the left, set up and hold your ground, or drive straight ahead.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 7-4: On normal downs, offensive linemen assume a three-point stance.

But in a definite passing situation, such as third-and-long, being in a two-point stance is perfectly fine. Moving and maintaining positional leverage is easier and quicker from a two-point stance (see the “Leverage” section later in this chapter for more information). You can also run a draw or trap play from that position.

By the same token, if it’s first-and-10, an offensive tackle may be able to remain in the up position. Say the play is a run designed away from the tackle. From a two-point, up position, he can pull to the inside and help block for the ball carrier. Note: Linemen want to change stances occasionally to prevent defensive players from zeroing in on exactly what the offense is doing; this changing is known as giving the defensive player different looks.

A solid base

An excellent offensive lineman is able to maintain proper balance. The key to proper balance is having a solid base. A lineman’s feet should be set a little wider than the width of his shoulders; that way, the torso is set like a perfect upside-down T. If the lineman can maintain this stance, in most cases he won’t be knocked off his feet.

If offensive linemen can maintain a good base, they can utilize their feet and whatever quickness they have. The same principle applies in boxing and basketball. A boxer always maintains that good base while keeping any lean to a minimum. He doesn’t want to overextend his body to one side, thus becoming more susceptible to being knocked off his feet. A basketball player on defense wants to be able to move right and left while maintaining a good center of gravity.

Leverage

Maintaining positional leverage is important for an offensive lineman. He needs to anticipate where the defensive player is going and then get himself between that player and the quarterback, whom he’s trying to protect. The point between the blocker and the quarterback, where the offensive lineman wants to meet the defender he plans to block, is called the intersection point. The offensive lineman needs to reach that point as quickly as possible. The slower the lineman assumes that position, the easier it is for his opponent to get him turned. That’s really what the defensive player is trying to do — turn the offensive lineman. After the offensive lineman is turned, the defensive player can shorten his distance to the corner. And after he accomplishes that, the defender can make an inside move because he has the offensive lineman pointed in the wrong direction.

Toughness

An important ingredient in offensive line play is toughness. Generally, toughness is an attitude a player develops over time. He must have a lot of self-pride and tell himself that no one will beat him. Being tough is a big part of every sport, and it’s a sign of a true competitor.

So much of toughness is mental. Many times, a football game is like a 15-round prizefight. At some point, one of those boxers slows down. I don’t want to say that he quits, but working hard simply becomes less important to him. That phenomenon happens on a football field, too, and that’s where mental toughness comes in. Toughness is essential when run-blocking because it’s basically about being tougher than your opponent and wearing him down. Linemen win the fight when they rob their opponents of mental toughness.

Standing together: The offensive line

Standing together: The offensive line

Offensive linemen tend to hang in a group: They practice together and go out together.

For example, in 1997, the Denver Broncos had a typical group. Denver’s offensive line instituted a kangaroo court — no defense attorneys allowed — in which they fined each other for being quoted in newspapers or talking on radio shows. The plan was for them to be anonymous; they were against publicity. In fact, they fined each other if they received a game ball, usually awarded by the captain or coach for a well-played game. And they fined Pro-Bowler Gary Zimmerman for being a prima donna because he missed training camp during a contract negotiation.

Prior to the Super Bowl, when the NFL ordered the Bronco linemen to talk — 2,000 reporters were asking questions every day — they bit their tongues when they heard how the more-talented Green Bay Packers defensive line was too powerful for them. On game day, they opened huge holes for running back Terrell Davis, who scored three touchdowns and rushed for 157 yards in Denver’s 31-24 victory.

When their teammates declared that the offensive line deserved the Super Bowl MVP award for blocking for Davis and protecting quarterback John Elway, the linemen thought that was definitely a bad idea. They would have had to fine themselves $1,000 or more for accepting such an honor.

Repetition

Another key to an effective and cohesive offensive line lies in its practice repetition. On any level, many of the best running teams are those that run three or four basic plays. They keep repeating them, doing them over and over until they’re so proficient that no opponent can stop them. In NFL training camps, offensive lines constantly work together, everyone going through the hard times, the long, hot muggy days — everyone working when he’s tired. At some point, you have to rely on the guy next to you. Working together over and over in the heat of the day can develop real cohesiveness.

Uncovering a Lineman’s Worst Offense: Penalties

When the ref blows the whistle because an offensive lineman committed a transgression, he blows the whistle because the lineman did one of the following:

· Clipping: When an offensive lineman blocks an opponent from behind, hitting him in the back of the legs or in the back. The infraction costs the offense 15 yards. However, clipping above the knee is legal within 3 yards of the line of scrimmage.

· Chop blocking: This dirty play (which draws a 15-yard penalty) is when a lineman dives at an opponent’s knees anywhere outside a designated area 3 yards beyond the line of scrimmage. The same block is considered legal when it occurs within 3 yards of the line of scrimmage. Go figure. The worst chop block is when linemen double-team a defender; one restrains the player around the shoulders while another hits him below the waist.

· Encroachment: Encroachment happens when a player enters the neutral zone before the ball is snapped and makes contact with the opposition. This is a 5-yard penalty. The offense repeats the down.

· False start: A false start is when an offensive lineman who’s in a stance or set position moves prior to the snap of the ball. This is a 5-yard penalty with a replay of the down.

· Helping the runner: After the ball carrier crosses the line of scrimmage, an offensive lineman can’t push or pull him forward, helping him gain extra yardage. Helping the runner is a 10-yard penalty with a replay of the down.

· Holding: When an offensive lineman grabs and holds onto a defensive player, it’s called holding, and it’s one of the worst things an offensive lineman can get caught doing. An offensive lineman is whistled for holding when he grabs an arm or a jersey, or even tackles a player who has managed to get around him. Linemen are allowed to use their hands, but they can’t use them to clamp onto an opposing player and limit his movement. If a lineman is caught holding a defensive player in the NFL, the penalty is 10 yards from the line of scrimmage.

Now, some people will tell you that offensive linemen hold on every play, but mainly those accusations are coming from defensive guys like me. Generally, if the offensive lineman’s hands are inside the opponent’s shoulder and his chest area (where the jersey number is), he can grab and hold all he wants as long as he keeps the defender in front of him. But if a defender goes to the ground really fast for no apparent reason, it’s obvious that he’s being held, even if the offensive lineman’s hands are inside.

· Ineligible receiver downfield: A quarterback would never throw the ball to his blockers, but the blockers can be penalized for running downfield if they aren’t trying to block defensive players. Linemen who are no longer blocking or have lost their man can’t run past the line of scrimmage when the quarterback is attempting to pass. Ineligible receiver downfield is a 5-yard penalty with a repeat of the down.

· Offside: This happens when an offensive player lines up over the designated line of scrimmage, trying to gain an edge on blocking or simply forgetting where he should be. Generally, the lineman either places his hand over the line of scrimmage or tilts his upper body over the line of scrimmage. Offside is a 5-yard penalty with a repeat of the down.

Getting Acquainted with Blocking Terms

You hear a lot of terms thrown around when it comes to blocking. Knowing one type of block from another really isn’t that important unless you’re trying to impress a diehard fan or you happen to play on the offensive line. If you’re interested, here’s the lowdown on some of the most common blocking terms:

· Cut-off block: Generally used on running plays, which are designed to allow a defensive player to come free, or untouched, across the line of scrimmage. After that happens, an offensive lineman deliberately gets in the way of this on-rushing defender. This block is sometimes called an angle block because the offensive lineman hits the defensive player from the side, or from an angle.

· Chop block: The legal variety is used within 3 yards of the line of scrimmage to slow the opposition’s pass rush. A lineman blocks down low with his shoulders and arms, attempting to take the defender’s legs from underneath him and stop his momentum. If this play occurs 3 yards or more beyond the line of scrimmage, the blocker is penalized 15 yards. Defensive players wish this type of block would be outlawed permanently on all parts of the playing field.

· Drive block: This one-on-one block is used most often when a defensive lineman lines up directly over an offensive lineman. The blocker usually explodes out of a three-point stance and drives his hips forward, delivering the block from a wide base while keeping his head up and his shoulders square.

· Double-team: Two linemen ganging up on one defensive player is known as double-teaming. It’s more common on pass plays when the center and a guard work together to stop the penetration of a talented inside pass-rusher. However, the double-team also works well on running plays, especially at the point of attack or at the place where the play is designed to go. The double-team blockers attack one defender, clearing out the one player who might stop the play from working.

· Man-on-man blocking: This is the straight-ahead style of blocking, with a defender playing directly over you and you driving straight into him. Most defenses use four linemen, so man-on-man blocking is common on pass plays, with each offensive lineman choosing the opponent opposite him, and the center helping out to either side.

· Reach block: A reach block is when an offensive lineman reaches for the next defender, meaning he doesn’t block the opponent directly in front of him but moves for an opponent to either side. The reach block is common on run plays when the play calls for a guard to reach out and block an inside linebacker.

· Slide block: This is when the entire offensive line slides down the line of scrimmage — a coordinated effort by the line to go either right or left. It’s a good technique when the quarterback prefers to roll or sprint right, running outside the tackle while attempting to throw the football. In that case, the line may slide to the right to give the quarterback extra protection to that side. With a talented cutback runner, this scheme may give the illusion of a run to the right, as the line slides that way while the ball carrier takes an initial step to the right and then cuts back to his left, hoping to gain an edge.

· Trap block: In a trap block, the offensive line deliberately allows a defensive player to cross the line of scrimmage untouched and then blocks him with a guard or tackle from the opposite side or where he’s not expecting it. The intent is to create a running lane in the area that the defender vacated. The trap block is really a mind game. The offense wants the defender to believe it has forgotten about him or simply missed blocking him. After the defender surges upfield, across the line of scrimmage by a yard or two, an offensive lineman blocks him from the side.

Depending on the play’s design, this block can come from a guard or a tackle. Teams run this play to either side, and it’s important for the center to protect the back side of this lane, negating any pursuit by the defense. The trap block is also called an influence block because you want to draw the defender upfield and then go out and trap him. Good passing teams tend to be good trapping teams because defenders usually charge hard upfield, hoping to reach the quarterback.

· Zone block: In this block, each lineman protects a specific area or zone. Even if the defensive player leaves this area, the blocker must stay in his zone because the play or ball may be coming in that direction and the quarterback wants that area uncluttered. Blocking in a zone is generally designed to key on a specific defensive player who’s disrupting the offensive game plan.