Football For Dummies (2015)

Part II

Go, Offense!

Chapter 6

Hitting the Ground Running

In This Chapter

![]() Looking at the roles of the fullback and running back

Looking at the roles of the fullback and running back

![]() Understanding why all sizes and shapes can excel at the running game

Understanding why all sizes and shapes can excel at the running game

![]() Getting acquainted with the running game’s nuances

Getting acquainted with the running game’s nuances

![]() Taking a look at three running back-focused offensive formations

Taking a look at three running back-focused offensive formations

![]() Reviewing basic running plays

Reviewing basic running plays

Running back may be the most physically demanding position in football. A great running back, whose productivity dictates his team’s success, is asked to take a tremendous beating on a weekly basis. Every game he faces 11 angry men who have a license to physically punish him. Rarely does one defensive player bring down a great running back. He gets hit from every angle — high and low. Often, one player grabs hold of the running back while a number of defenders take clean shots at him.

One of the toughest football players I played with was running back Marcus Allen. Despite the continual beating he took, Allen would pick himself off the ground and, without showing any emotion, walk back to the huddle and prepare for the next play. I don’t know how many times I saw Marcus look like he’d just gotten his head taken off and then come right back for more on the very next play. He was especially determined at the goal line, scoring a then-NFL-record 123 rushing touchdowns even though everyone in the stadium knew he would be running with the ball.

One of the toughest football players I played with was running back Marcus Allen. Despite the continual beating he took, Allen would pick himself off the ground and, without showing any emotion, walk back to the huddle and prepare for the next play. I don’t know how many times I saw Marcus look like he’d just gotten his head taken off and then come right back for more on the very next play. He was especially determined at the goal line, scoring a then-NFL-record 123 rushing touchdowns even though everyone in the stadium knew he would be running with the ball.

This chapter goes into detail about what makes a great running back — or a good one, for that matter. Obviously, a running back needs to be able to do more than just run with the football. A running back must also know his assignments, know the opposing defenses, and be aware of all the players on the field. So, in this chapter, I explain the many different running plays and the varied styles and types of people who fit the mold of a running back.

An Overview of the Ground Game

In football, the ground game refers to running the football (as opposed to passing it). Running the ball is the basic premise of football, and it’s the easiest way to move the ball. A team runs three times and gains 10 yards, and that’s good enough for a first down and another set of four downs. What could be easier? In youth football, every team runs. After all, what 11-year-old can pass like former Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino? Plus, learning the fundamentals of running the ball is much easier than learning how to run pass routes.

In football, the ground game refers to running the football (as opposed to passing it). Running the ball is the basic premise of football, and it’s the easiest way to move the ball. A team runs three times and gains 10 yards, and that’s good enough for a first down and another set of four downs. What could be easier? In youth football, every team runs. After all, what 11-year-old can pass like former Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino? Plus, learning the fundamentals of running the ball is much easier than learning how to run pass routes.

Most championship football teams are excellent at running the football. The Denver Broncos won the Super Bowl in 1998 because they had a better running game than the Green Bay Packers. The Broncos could run, and the Packers couldn’t stop them and their talented running back, Terrell Davis. In fact, Denver’s offensive line was really fired up for that game — they wanted to block and open holes — because they felt that the Packers, the media, and some NFL insiders weren’t giving them enough respect.

The New York Giants won their second Super Bowl after the 1990 season, beating a superior Buffalo Bills team, because they could run the ball and keep the clock moving. They also kept the ball away from Buffalo’s high-powered offense. This ploy is called ball control, which is a common football term. Running the ball is the best way to maintain possession and keep the clock moving when a team is ahead because the clock doesn’t stop if a player is tackled in bounds. However, if the quarterback throws an incompletion, the clock stops. Stopping the clock is advantageous to the defense; it gives them a breather and the hope that they may get the ball back. So when a team is running the football successfully, usually it’s physically whipping the other team. And that’s the object of the game!

The NFL has become somewhat of a pass-happy league, but the running game is still vitally important. In 2013, 13 running backs rushed for more than 1,000 yards, with LeSean McCoy of the Philadelphia Eagles leading the way with 1,607 yards. He averaged 5.1 yards per carry.

Football’s predecessor: Rugby

Men have been running with a ball for almost two centuries. Before football, people were fascinated by a sport called rugby, which was developed by an Englishman in 1823. Players in this sport are tackled by more than one opponent, and the runner isn’t protected by a helmet or shoulder pads. Football is based on rugby — but the men who designed football were smart enough to add protective gear to the mix.

Meeting the Men Who Play the Ground Game

Understanding what’s going on during running plays is much easier when you know who’s responsible for the running game. The next time you see an offense set up, look for the two players who line up in the offensive backfield (the area of the field behind the quarterback and the line of scrimmage). These players are the running backs. The smaller one is the main ball carrier, and the larger one is the guy charged with protecting the ball carrier. Read on to find out what each type of running back does, who tends to play in these positions, and how each player lines up behind the quarterback.

The halfback, a team’s principal ball carrier

On most teams, the principal ball carrier is called the halfback (also called the tailback or the running back). When teams — be they high school, college, or NFL teams — find a good running back, they give him the ball. And they give it to him as often as he’s willing and able to carry it. (Check out Figure 6-1 to see former Alabama tailback Mark Ingram in action.)

Photo credit: © Joe Robbins/Getty Images

Figure 6-1: Tailback Mark Ingram (22) of the Alabama Crimson Tide fights off an Arkansas Razorbacks’ tackler in 2010.

Most runners would probably tell you that they wouldn’t mind carrying the ball even more often than they actually do. Toting the football is a status symbol, after all. The NFL record for rushing attempts in a single season belongs to Larry Johnson, then of the Kansas City Chiefs, who carried the ball 416 times in the 2006 season. That’s an astonishing 26 carries per game!

The fullback, protector of the halfback

When a team employs two running backs in the offensive backfield, the bigger of the two is usually called the fullback. He’s there to block and clear the way for the halfback, who’s the main ball carrier. You may think that the fullback’s job is a thankless one, but most fullbacks get a lot of satisfaction from making a great block (generally on a linebacker) and winning the physical battle against players who tend to be bigger than they are.

In the old days, some of the best runners were fullbacks. Marion Motley of the 1949 Cleveland Browns weighed almost 240 pounds and carried defenders down the field. Cookie Gilchrist was a 252-pound fullback with the Buffalo Bills in the mid-1960s; he was one devastating blocker and could run, too. So could 237-pound Larry Csonka, a former Miami Dolphin, who, along with 230-pound John Riggins of the Washington Redskins, was the dominant fullback of the 1970s.

In the old days, some of the best runners were fullbacks. Marion Motley of the 1949 Cleveland Browns weighed almost 240 pounds and carried defenders down the field. Cookie Gilchrist was a 252-pound fullback with the Buffalo Bills in the mid-1960s; he was one devastating blocker and could run, too. So could 237-pound Larry Csonka, a former Miami Dolphin, who, along with 230-pound John Riggins of the Washington Redskins, was the dominant fullback of the 1970s.

It’s interesting to note that because of the way offenses have evolved, especially in college football, the traditional fullback position appears to be going the way of the dinosaur. Some NFL teams have no true fullback on their roster. The spread offense, with its emphasis on passing, doesn’t require a fullback. Big, strong, fast players who in previous years might have played fullback are now playing on the other side of the ball, in the linebacker position.

Recognizing that Running Backs Come in All Sizes and Shapes

You may hear football coaches say that a particular player is the prototype performer at a particular position, but no such prototype exists at running back. Running backs come in all sizes and shapes. Little guys like former Detroit Lion Barry Sanders, former Chicago Bear Walter Payton, and former Buffalo Bill Thurman Thomas, who were quick and slippery players, excelled at the highest level. Big brutes like Jim Brown of the Cleveland Browns, Earl Campbell of the Houston Oilers (now the Tennessee Titans), John Riggins of the Washington Redskins, and Jim Taylor of the Green Bay Packers also had successful NFL careers.

Running back Emmitt Smith, who scored a then-record 25 touchdowns in 1995 and who holds the NFL record for yards gained, was an example of the tough, physical inside runner who weighed only 210 pounds. Pittsburgh Steelers tailback Jerome “The Bus” Bettis was 40 pounds heavier than Smith, but I still considered him a halfback rather than a fullback because he was the main runner on his team. And I can’t forget former Dallas Cowboy Tony Dorsett, the great Marcus Allen, and former San Francisco 49ers Roger Craig and Tom Rathman — all good backs, but never listed as little guys or big brutes.

Next, let me clear up the myth that you have to be extremely fast to be an excellent running back. Marcus Allen had only average speed; in fact, some scouts thought he was too slow. But in his outstanding career, he scored 145 touchdowns and gained 12,243 yards rushing. Allen was elected to the Football Hall of Fame on his first try in 2003. He was football’s finest north/south runner — which means he didn’t mess around dancing “east” or “west” behind the line of scrimmage. When trapped by defensive players, the quickest and best way to gain yards is to go straight ahead; that’s the primary trait of a north/south runner.

Next, let me clear up the myth that you have to be extremely fast to be an excellent running back. Marcus Allen had only average speed; in fact, some scouts thought he was too slow. But in his outstanding career, he scored 145 touchdowns and gained 12,243 yards rushing. Allen was elected to the Football Hall of Fame on his first try in 2003. He was football’s finest north/south runner — which means he didn’t mess around dancing “east” or “west” behind the line of scrimmage. When trapped by defensive players, the quickest and best way to gain yards is to go straight ahead; that’s the primary trait of a north/south runner.

Little guys slip by opponents in the open field. They’re difficult to grab hold of and tackle — it’s almost like their shoulder pads are covered with butter. Barry Sanders fell into that group. So did Dorsett and Lionel “Little Train” James, who played for San Diego in the 1980s. On the other hand, big brutes like Jim Brown simply run over everyone. Brown never concerned himself with making tacklers miss him. At some point, every coach looks for a big back who can run over everyone in his way.

Regardless of their size or skill level, the common denominator among all these men is that they were physically tough, determined, and talented football players. Any type of runner can be a good running back, as long as he’s playing in the right system and gets help from his teammates.

Exploring Running Back Fundamentals

Running backs need more skills than players at other positions. That’s because on any given play, a running back may run the ball, catch a pass, or block an opposing player. Occasionally running backs are even called upon to throw a pass or kick the ball. To help you appreciate what running backs do, the sections that follow look at what goes into playing this very important position.

The basic skills

On most football teams, the running back is the best athlete on the team. The demands on him, both physical and mental, are great. Every running back must be able to do the following well:

· Line up in the right stance: The most common stance for a running back is the two-point stance. A tailback in the I formation (I tell you all about this in the later “Lining Up: The Formations” section) often uses the two-point stance with his hands on his thighs, his feet shoulder width apart, and his weight on the balls of his feet. His head is up, his legs are slightly bent at the knees, and his feet are parallel to one another, with his toes pointed toward the line of scrimmage. (For more information on running back stances, see the later “The stances” section.)

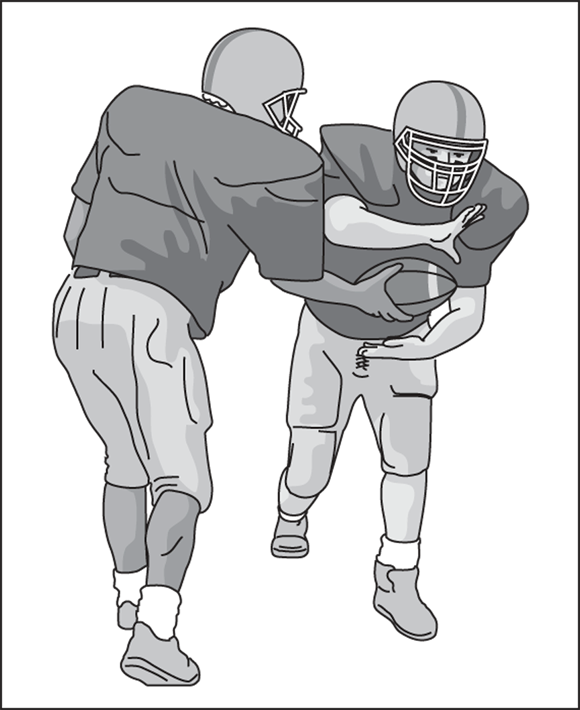

· Receive a handoff: A runner must receive the football from the quarterback without fumbling. To do this properly, his arms must form a pocket outside his stomach. If the back is right-handed, he bends his left arm at the elbow in a 90-degree angle, keeps his forearm parallel to the ground, and turns up the palm of his left hand. His right arm is up to receive the ball so that when the quarterback places the ball in his stomach area, his right forearm and hand close around it. Figure 6-2 shows how a running back takes a handoff and holds the ball while running. After he has possession of the ball, the back grips the ball at the tip and tucks the other end into his elbow with one side of the ball resting against his body (so his arm is in somewhat of a V-shape).

· Run at top speed: Ideally, a running back is running at near top speed when he grabs a handoff. His head is upright and his shoulders are square to the line of scrimmage. He’s also leaning forward slightly to keep his body low, and his legs are driving forward. When making cuts, the back plants and accelerates off the foot that’s opposite of the direction he’s running (for example, if he wants to go left, he plants on his right foot). When running behind a blocker, he’s behind the blocker’s outside hip. When the block is made, the back cuts quickly behind the blocker’s inside hip when turning upfield. For cut-back running, the back fakes a step away from the defender (trying not to shift too much weight) and then turns quickly to the inside of the defender (of course, the defender must move for the cut-back to be successful).

· See the field: When you watch video highlights of a great running back like Barry Sanders of the Detroit Lions, you’d swear he had eyes in the back of his head. How else can you explain his cuts and moves and his escapes from defensive trouble? Like a basketball guard running a fast break, a back needs to have peripheral vision. He needs to be able to see what’s coming at him from the corners of the field. Backs with exceptional speed (4.4 seconds in the 40-yard dash) can gain many more yards by seeing where the defensive pursuit is coming from and running away from it. However, backs without great speed can be successful by sensing danger while trying to maintain a straight line to the end zone (these backs are called north/south runners). But backs with great speed can outrun many defenders by heading to the corner of the end zone if a defender is 10 yards away to their left or right.

· Block for another back: A team’s principal running back is rarely a good blocker. The best blockers among the backs are the fullbacks, who are asked to block players 30 to 100 pounds heavier than they are. A running back needs to stay low and explode into the defender’s upper body while using his hands (in closed fists) and forearms to make contact. A lot of backs try to block a linebacker or defensive back low (at his legs), but this technique is rarely successful. Many defensive players are capable of jumping up and then shoving the back down to the ground as they move past him. Coaches want their backs to get a piece of the defender and knock him off his line to the quarterback or ball carrier.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-2: One of a running back’s main concerns is protecting the ball by receiving the quarterback’s handoff properly.

The job description

A running back has a responsibility, or assignment, on every play. I think running backs have the toughest job on the football field because they have to not only know every play like a quarterback but also make physical contact on virtually every down.

No matter how fast an athlete is, how big a brute he is, or how slippery or quick he is, he won’t be able to play as a running back if he doesn’t have a brain and can’t think on his feet. I think the main reason many outstanding college runners never make it in professional football is that the pro game simply overloads their brains.

No matter how fast an athlete is, how big a brute he is, or how slippery or quick he is, he won’t be able to play as a running back if he doesn’t have a brain and can’t think on his feet. I think the main reason many outstanding college runners never make it in professional football is that the pro game simply overloads their brains.

Here’s a rundown of a running back’s job description:

· He’s an every-minute player. While he’s on the field, he never has a minute to let up, and he never has a chance to take a play off. He can’t afford to line up and merely go through the motions. When he doesn’t have the ball, he must follow through with his fakes and pretend that he has the ball.

· On every play, he must know what down it is and how many yards the team needs for a first down. He must know when to lower his shoulder and go for a first down and when to keep a drive alive by making a move and gaining a little extra yardage, helping his team move into scoring range.

· He must know the time on the clock in order to know when to go out of bounds and when to turn upfield and gain extra yardage. Stopping the clock is critical when a team is behind in the score.

· He must know the defense’s various alignments and then adjust his thinking to those alignments on pass plays and running plays. On a pass play, he must know the protection scheme because he may be asked to throw a block to give the quarterback time to pass.

· He must know every play and all its variations. For example, on one running play, he may have to block a linebacker. But on the same play called against a different defensive front, he may be asked to block a defensive end.

On running plays, a running back must know the opposition’s defensive schemes so he can predict which defender will be the first guy coming to make the tackle. Although this information may not be important to the runner carrying the ball, it’s valuable for the other back who’s asked to block on the play.

· He must know every pass route called because he may be the first receiving option on a play. He must know the defense’s coverage in order to adjust his route accordingly. For example, if the linebacker goes out, he may have to go in, and vice versa. He must know how deep he has to get on every pass route so that he’s timed up with the quarterback’s drop. Because the quarterback may throw the ball before the runner turns to catch the ball, he must run the exact distance; if he doesn’t, the timing of the play will be messed up.

· He must know every hole number in the playbook. A typical NFL playbook may contain between 50 and 100 running plays. The holes (the spaces opened up by blockers), which are numbered, are the only things that tell the running back where he’s supposed to run with the ball. The play will either specify the hole number or be designed for a specific hole.

College running backs versus pro running backs

In college, coaches give a great high school running back a scholarship, and they have him for four years. Now, it doesn’t look good for your program if you beg a player to come to your school and then end up cutting him or taking away his scholarship because he doesn’t live up to your expectations. This is what I mean when I say that he’s yours for four years.

The difference for pro running backs is that the NFL is a big business. Running backs can be signed to big contracts, but teams can always cut them and lose nothing but a few days or weeks of coaching time and a few dollars. Today, such dismissals are viewed simply as bad money deals or bad investments. Therefore, when a head coach finds a runner who can run for more than 1,000 yards a season, score whenever he needs to, and carry the team when the quarterback is having an off day, he knows he has a winner.

The stances

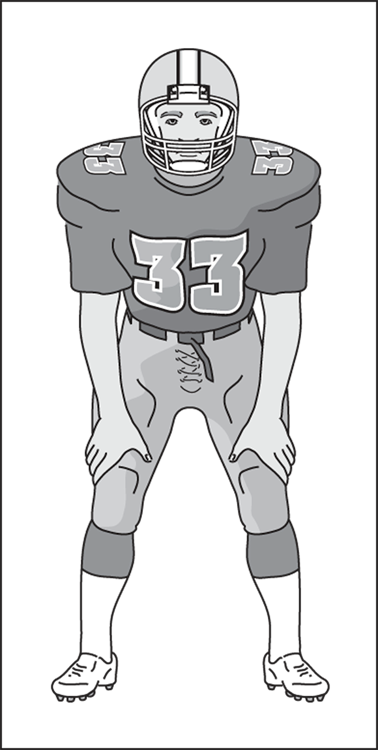

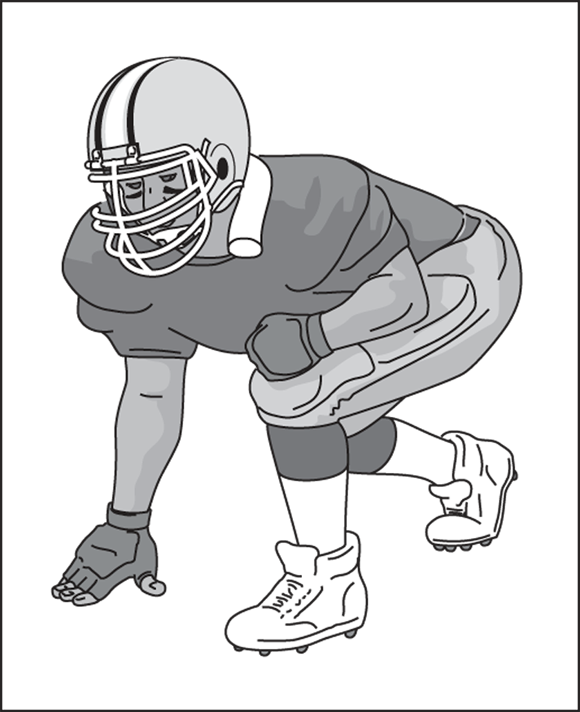

A running back can use two stances: One is the up stance, in which he has his hands resting on his thighs, a few inches above his knees, as shown in Figure 6-3. This stance is also called the two-point stance. The second is the down stance, in which he puts his right hand on the ground like a lineman, as shown in Figure 6-4. It’s also called the three-point stance because one hand and both feet are on the ground.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-3: A running back’s up stance (or two-point stance).

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-4: A running back’s down stance (or three-point stance).

Runners can use the two-point stance when they’re in the split-back formation, with one back aligned to the left of the quarterback and one to the right. However, most coaches prefer their runners to use the three-point stance in this alignment because they believe it provides the runner with a faster start than the two-point stance — much like a sprinter bursting from his blocks. Some runners remain in the two-point stance in split backs, which can tip off the defense that they’re going to pass-protect for the quarterback or run out for a pass. The running backs can then resort to a three-point stance with the intention of confusing the defense.

In the I formation, so named because the center, quarterback, fullback, and halfback line up behind one another to form a letter I, the deep back is always in a two-point stance. The fullback in the I formation is in front of the tailback. He can be in either a two-point or a three-point stance because he’s blocking on 95 percent of the plays. The two-point stance is better on passing downs because it enables the running back to see the defensive alignment better — meaning he can see whether a linebacker may be blitzing, especially if he must block this defender. The three-point stance is better for blocking because the running back can exert his force upward and into the defender’s chest and upper body.

The number one priority

The most important aspect of a running back’s game is protecting the football. On the first day of practice, the first thing the coach tells his running backs is this: If you don’t protect the football, you won’t play. By protecting the football, I mean not fumbling the ball and leaving it on the ground where the opposition can recover it and gain possession. How well you protect the football is more a matter of how well you concentrate, not how big you are.

To help them protect the ball (and themselves), running backs have to know pursuit and angles. I’m talking football language here, not physics. What I mean is that the runner must understand where the defensive players are coming from (the pursuit) and from what direction (the angle) they plan on tackling him. If a runner understands these basic principles, he can figure out the direction the defensive players are coming from and prepare for contact and protecting the football.

Before contact, the running back braces the ball against his body while protecting the outside of the ball with his hand and forearm. Some backs prepare for the collision by wrapping their other arm around the football as well. Also, the back dips his shoulders and head and rolls his shoulders inward away from where he expects the first contact to come from. When facing smaller defenders, the running back may use a stiff arm (extending his free hand) to jostle the defender in his face mask or shoulder area. A back uses a stiff arm to push a tackler away from him or to reduce the tackler’s ability to go after his legs.

Dorsett goes the distance

Dorsett goes the distance

A player can return a kick, punt, or interception for 100 yards or more to score a touchdown, but the longest possible run is 99 yards. Former Dallas Cowboys running back Tony Dorsett, a Heisman Trophy award winner from the University of Pittsburgh, covered exactly that distance in 1983.

The amazing part about the play is that Ron Springs, the Cowboys’ other running back, was supposed to get the ball; the play was designed for him. But Springs misunderstood quarterback Danny White’s call and left the huddle, returning to the sidelines. With Springs gone, Dallas had only ten players on the field. And because quarterbacks don’t do much blocking, only 8 Cowboys were available to block 11 Minnesota Vikings (I say only 8 because one of the remaining 9 was Dorsett, who was carrying the ball).

Dallas, coached by the highly specialized and inventive Tom Landry, always did a lot of substituting. But White didn’t know that Springs had left the huddle. As White turned away from the line of scrimmage, looking for Springs, he instead came face to face with Dorsett. White did what any panicked quarterback would do: He handed the ball to Dorsett. But the play didn’t end up being a flop. Dorsett faked left, stopped, and then headed around the right end. He broke through the first line of defenders and was off to the races.

Dorsett’s run still stands as the longest run from the line of scrimmage in NFL history. It may be equaled someday, but it will never be surpassed.

Lining Up: The Formations

An offensive formation is how the offense aligns all 11 of its players prior to using a particular play. A team can run or pass out of many formations, but for this chapter, I selected three backfield formations that focus specifically on running backs. One is the pro-set, which is also known as the split-back or split T formation. Another is the I formation — where both runners are aligned together behind one another and behind the quarterback and center. The third formation is the I formation’s hybrid, the offset I formation. Most teams give these offset formations names like Jack, Queen, Far, Near, and so on.

Here’s a breakdown of what the three formations look like:

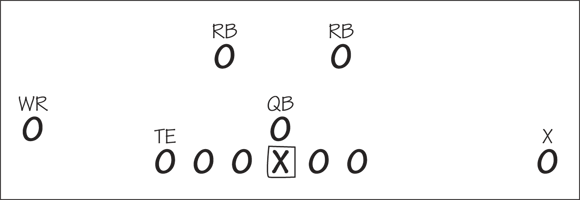

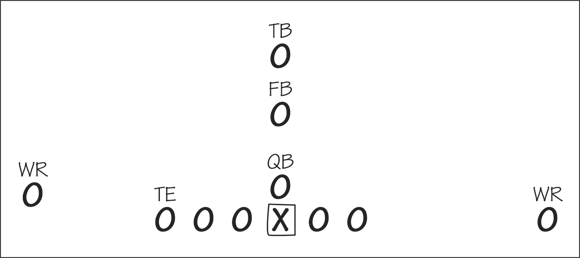

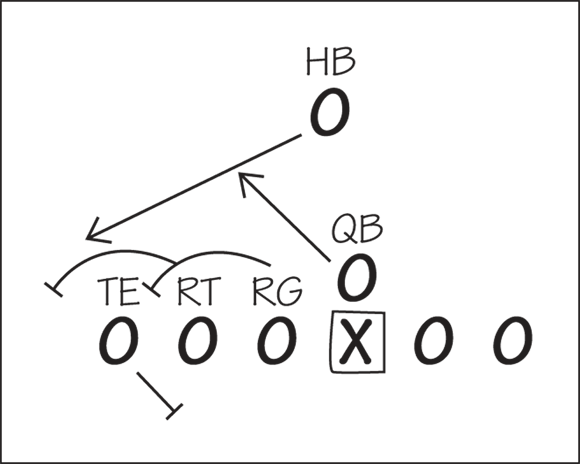

· Split-back formation: In the split-back formation, the runners are aligned behind the two guards about 5 yards behind the line of scrimmage, as shown in Figure 6-5. Teams use this formation because it’s difficult for the defense to gauge whether the offense is running or passing. With split backs, the backfield is balanced and not aligned toward one side or the other, making it more difficult for the defense to anticipate what the play will be. This formation may be a better passing formation because the backs can swing out of the backfield to either side as receivers.

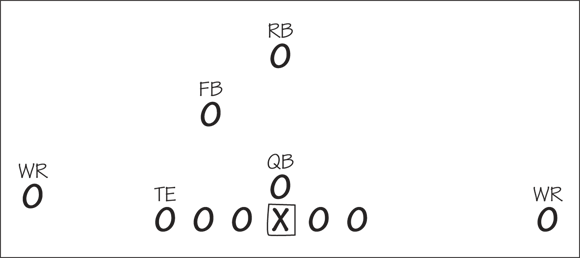

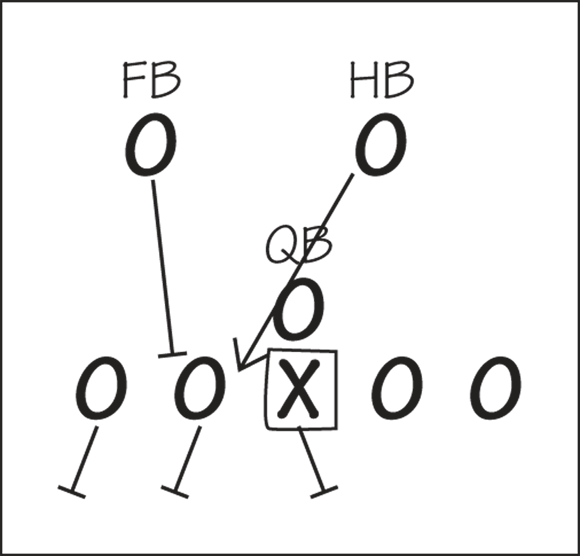

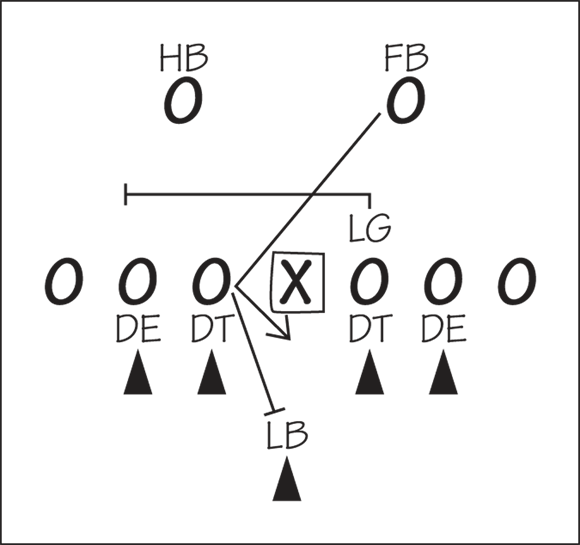

· I formation: In the I formation, the tailback (TB) — the runner who will carry the ball — can place himself as deep as 7 yards from the line of scrimmage, as shown in Figure 6-6. By stepping this far back, the runner believes he’ll be in full stride when he nears the line of scrimmage. Consequently, the I formation is ideally suited to a team with a great running back. Also, the depth allows him to have complete vision of his blockers and the defensive players’ first reaction to the run. This formation is called the I because the quarterback (QB), fullback (FB), and tailback form an I, with the fullback between the quarterback and tailback.

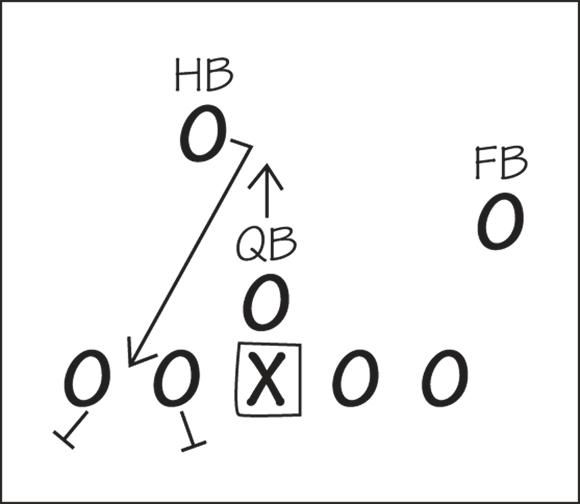

· Offset I formation: In the offset I formation, the running back (RB) remains deep, 5 to 7 yards from the quarterback. When the running back is this deep, the majority of the time the team plans to run the ball. The fullback (FB), or blocking back, can be as close as 3 yards to the line of scrimmage, as shown in Figure 6-7. The other back wants to be close to his target: the defender he must block. A good fullback needs only 2 yards before making blocking contact. Also, he’s deep enough in case the play requires him to go in motion to either side and swing to the outside for a possible reception. The fullback can be set to the strong side or the weak side of the formation.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-5: In the split-back formation, the two RBs line up behind the two guards.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-6: In the I formation, the TB lines up 7 yards behind the line of scrimmage with a FB in front of him.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-7: The FB is set to the strong side in this version of the offset I formation; the RB remains deep.

Single wing

The single wing was an offensive formation that was popular in the early years of the NFL. Pop Warner developed the formation around 1908. It used four players in the backfield: the quarterback, tailback, wingback, and fullback. In the single wing, the tailback, not the quarterback, was the primary passer and runner. The quarterback was a blocking back like today’s fullback.

In this formation, the quarterback was positioned close to the line of scrimmage and in a gap (the spacing) between two offensive linemen. The wingback was aligned behind and outside the strong-side end. The fullback was a few steps from the tailback and also aligned to the strong side. Back then, the offensive line generally was unbalanced — two linemen were to one side of the center and four were to the other side. The strong side was the side where the four offensive linemen were lined up. The ball was snapped to the tailback, not the quarterback, who was about 4 yards behind the center.

Most of the time, offenses ran the ball from the single wing; it was a power football formation. However, with the tailback doing a lot of spinning and faking, the single wing added deception. The tailback often would lateral the ball to another back. Teams would run reverses, counters, and trap plays from the formation while also passing the ball.

Walking through the Basic Running Plays

If you’re watching closely, you may notice your local high school football team using some of the same running plays that the NFL pros do. That’s because the following basic running plays are used in all levels of football:

· Blast or dive: Every team has the blast or dive run in its playbook; it’s the simplest of carries. Usually led by a blocking fullback, the running back takes a quick handoff from the quarterback and hits a hole between an offensive guard and a tackle. On some teams, this run ends up between a guard and the center. The offense calls this run when it needs a yard or two for a first down. The runner lowers his head and hopes to move the pile (or push through defenders) before the middle linebacker tackles him.

· Counter: This play is an intentional misdirection run on the part of the offense. The quarterback fakes a lateral toss to one back who’s heading right, running parallel to the line of scrimmage. He’s the decoy. The quarterback then turns and hands off to the remaining runner in the backfield, generally a fullback, who runs toward the middle of the line, hoping to find an opening between either guard and the center.

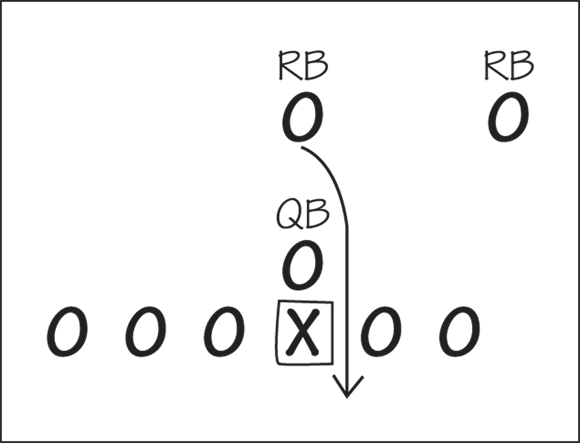

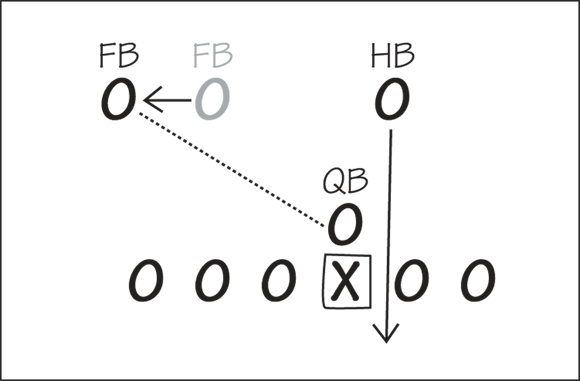

· Draw: This is a disguised run, which means it initially looks like a pass play. The offensive linemen draw back like they’re going to pass-protect for the quarterback (QB). The quarterback then drops back and, instead of setting up to pass, he turns and hands the ball to the runner, as shown in Figure 6-8. After the running back (RB) receives the ball, he wants to reach his maximum speed quickly to take advantage of the anticipated huge holes at the line of scrimmage. The goal of every draw play is to get the defensive linemen charging at the quarterback, only to be pushed aside by the offensive linemen at the last second. To fool the defense with this run, a team must have an above average passing game.

· Off-tackle: The off-tackle is the oldest run around — it’s a byproduct of the old single wing offense from more than 100 years ago (see the nearby “Single wing” sidebar for more information on this offense). It’s a strong-side run, meaning the halfback (HB) heads toward the end of the line where the tight end, the extra blocker, lines up. The runner wants to take advantage of the hole supplied by the tackle, tight end, and his running mate, the fullback (FB). He can take the ball either around the tight end, as shown in Figure 6-9, or outside the tackle. He hopes that the fullback will block the outside linebacker.

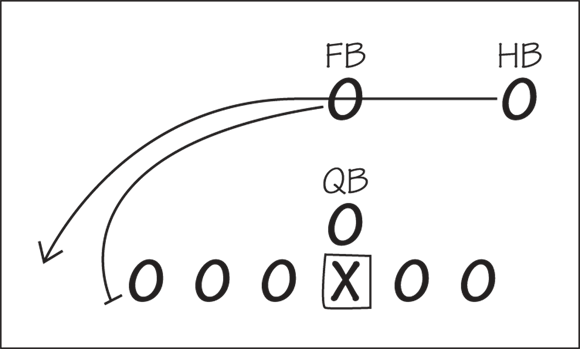

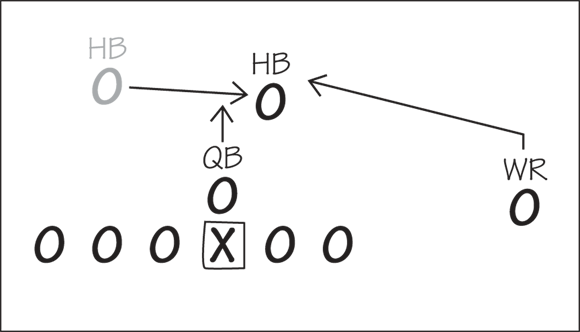

· Pitch: This run is usually from a two-back formation. The quarterback (QB) takes the snap and fakes a handoff to the first back (HB), who’s heading directly toward the line of scrimmage; he then tosses (or pitches) the ball laterally to the other runner (FB), who has begun to move to the outside, as shown in Figure 6-10. The runner can either take the pitch outside or cut back toward the inside. Pitch plays can be designed to go in either direction.

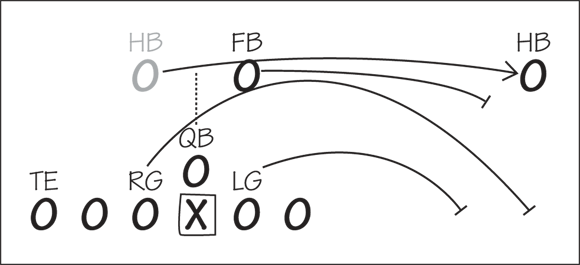

· Reverse: For this play, the halfback (HB) receives the handoff from the quarterback (QB) and then runs laterally behind the line of scrimmage. (The play can be designed for the back to run in either direction.) The ball carrier meets up with a wide receiver (WR) or flanker running toward him and then hands the ball to that receiver or flanker, as shown in Figure 6-11. The offensive line blocks as if the ball were intended for the halfback so that the defensive players follow him. After the receiver is in motion and has the ball, he runs in the opposite direction, or against the flow of his own blockers. This play really works if the receiver is a fast and tricky runner. It helps if the interior defensive players and linebacker fall for the halfback’s initial fake. Also, the weak-side defender, the last line of defense, must leave his position and chase the halfback. Otherwise, this weak-side defender is in perfect position to tackle the receiver.

· Slant: This run is exactly like it sounds. Instead of running straight toward the line of scrimmage, the runner (HB) slants his angle outside after he receives the ball, as shown in Figure 6-12. A slant is used to take advantage of defenses that over pursue, allowing offensive linemen to be more effective by pushing the defenders to one side.

· Sweep: This run is pretty common in every team’s playbook. As shown in Figure 6-13, it begins with two or more offensive linemen (which in the figure are labeled as LG and RG) pulling, or leaving their stances and running toward the outside of the line of scrimmage. The ball carrier (HB) takes a handoff from the quarterback (QB) and runs parallel to the line of scrimmage, waiting for his blockers to lead the way around the end. The run is designed to attack the defensive end, outside linebacker, and cornerback on a specific side. Most right-handed teams (that is, teams that have a right-handed quarterback) run the sweep toward the left defensive end. The sweep can begin with the other back faking receipt of a handoff and running in the opposite direction of where the sweep run is headed. Many teams simply have the other back, a fullback (FB), help lead the blocking for the ball carrier.

· Stretch: The stretch play, or outside zone run, has become more popular in recent years. The quarterback (QB) takes the snap from under center and sprints into the backfield to meet the ball carrier (HB) as he runs toward the edge of the formation, outside the tight end. As shown in Figure 6-14, the strong side guard and tackle pull to lead the runner as the tight end blocks down to seal off any defenders coming from the inside.

· Trap: Teams don’t use this run very often because it requires quick and agile offensive linemen, and most teams use big blockers these days. As shown in Figure 6-15, the trap is a sucker run that, like the draw, is intended to take advantage of the defensive players’ willingness to attack the offense. The trap works well against an aggressive defensive line and linebackers. On the trap, a guard (LG in the figure) vacates his normal area, allowing the defensive player to cross the line of scrimmage and have a clear lane into the backfield. The guard from the opposite side then moves across the line and blocks the defender. This action by the guard is called pulling, hence the term pulling guard. The trap play has to be well-timed, and after the ball carrier receives the ball, he must quickly dart through the hole behind the trap block.

· Veer: College teams run this play more often than pro teams do because it generally requires a quarterback who’s quick-footed and an excellent ball-handler — in other words, a quarterback who can run if he has to. As shown in Figure 6-16, the veer is a quick-hitting run in which the ball can be handed to either running back, whose routes are determined by the slant or charge of the defensive linemen. The term veer comes from the back veering away from the defense. In Figure 6-16, the quarterback (QB) hands off to the halfback (HB), who veers to the right behind his blockers.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-8: How the RB moves in the draw play.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-9: The FB clears a path for the HB in the off-tackle run.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-10: Faking a handoff to the HB and tossing the ball to the FB in the pitch run.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-11: For a reverse, the QB hands off to the HB, who then hands the ball to the WR.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-12: The HB runs to his right after aligning on the left side in a slant play.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-13: The sweep calls for the HB to follow the two pulling guards and FB around to the weak side.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-14: The stretch play allows the running back to quickly reach the edge of the formation.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-15: As the FB takes a handoff for the trap play, the LG pulls to his right.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-16: In the veer run, the QB hands off to the HB, who veers to the hole on the right.