Football For Dummies (2015)

Part III

The Big D

Chapter 11

Delving into Defensive Tactics and Strategies

In This Chapter

![]() Discovering how coaches pick which defenses to use

Discovering how coaches pick which defenses to use

![]() Familiarizing yourself with the 4-3 defense, the 3-4 defense, and other defenses

Familiarizing yourself with the 4-3 defense, the 3-4 defense, and other defenses

![]() Finding out what to do in the sticky situations

Finding out what to do in the sticky situations

Coaches will tell you that defenses win championships, and I’m not being prejudiced when I say that I agree with that statement. When I was in the right defense, in the proper alignment, that was when I had the best chance to succeed. When you’re in the right defense, it comes down to you beating the man in front of you. As an athlete, that’s all you can ask for.

The defense’s battle plans are exactly what this chapter is about. Every team enters a game with a basic strategy. This chapter explains the common strategies — the defense’s alignment and look — and how the defense can be “offensive” by dictating the style of play in a game. In this chapter, I cover all the basic defenses and help you figure out which defensive package works best against which offense.

Choosing a Base Defense

NFL coaches love to copy one another, primarily when a coach is successful with a particular offense or defense. For example, a lot of winning teams in the 1970s began to use the 3-4 defense (which uses three down linemen and four linebackers) as their base, or primary, defense. The 3-4 was the defense of choice in the 1980s; only Dallas, Chicago, and Washington preferred a 4-3 scheme (four down linemen and three linebackers). By the time the 1990s came to a close, the 4-3 defense was back in vogue, thanks mostly to the success that Jimmy Johnson had with the Dallas Cowboys in the 1990s. In the 2014 season, a slight majority of NFL teams used some form of the 4-3 as their base defense.

Basically, what you need to understand is that the goals of any type of defense are to

Basically, what you need to understand is that the goals of any type of defense are to

· Stop the opposition and get the ball back for the offense.

· Seize possession of the ball via a turnover. A turnover occurs when the defense recovers a fumble or secures an interception.

To compete with sophisticated offenses, defenses have had to keep pace. In fact, some rules have changed simply to negate suffocating defenses. These rule changes have caused defensive coaches to return to the chalkboards and film rooms to devise more dastardly plans — and nowadays, they even use computers to uncover offensive tendencies.

Most defenses are named by their fronts, or the number of defensive linemen and linebackers who align in front of the defensive backs. The most common front is the front seven: four defensive linemen and three linebackers, or three defensive linemen and four linebackers. It’s assumed in football parlance that a front seven also includes four defensive backs: 7 + 4 = 11 players on the field.

I want you to fully understand the history, the reason, and the success/failure rates for each defensive scheme. Knowing why a team uses a specific strategy is important. Choosing a defense is like a game of checkers: A coach wants his team to stay a few offensive moves ahead of its opponent, anticipating the opponent’s next move or play. The defense wants to prevent the offense from jumping over its defenders and reaching the end zone (or as they say in checkers, “King me!”). And, like checkers, you may sacrifice a piece in one area of the board (or field) to prevent the opponent from reaching your end of the board. The ultimate goal with any defense is to prevent a touchdown, so sometimes surrendering a field goal is a moral victory.

I want you to fully understand the history, the reason, and the success/failure rates for each defensive scheme. Knowing why a team uses a specific strategy is important. Choosing a defense is like a game of checkers: A coach wants his team to stay a few offensive moves ahead of its opponent, anticipating the opponent’s next move or play. The defense wants to prevent the offense from jumping over its defenders and reaching the end zone (or as they say in checkers, “King me!”). And, like checkers, you may sacrifice a piece in one area of the board (or field) to prevent the opponent from reaching your end of the board. The ultimate goal with any defense is to prevent a touchdown, so sometimes surrendering a field goal is a moral victory.

How I prepared to take on an opponent’s offense

How I prepared to take on an opponent’s offense

When I played for the Raiders in the 1980s, I brought computer printouts to the locker room to glance over on game days. Those computer sheets showed every formation the opposition planned to use against us (or so we thought).

When I went on the road, I carried my own VCR and brought tapes that Johnny Otten, the Raiders’ film guy, put together for me. I had him put every run play the team used on one tape, called a run cut-up, and every pass play on another, called a pass cut-up. These cut-ups showed every play that the opposition ran from a two-back formation, from the I-formation, and from the one-back formation (I fill you in on these formations in Chapter 6).

We watched hours of film during the week, but on Saturday nights I watched a couple more hours on my own and broke down every formation. By studying and reviewing all the formations, I was prepared. For example, when the opposition’s offense came to the line of scrimmage in a split-back formation, my mind immediately computed to “full left, 18 Bob Tray O,” a run play.

I know that jargon means nothing to you, but it tipped off my mind. I knew which play was coming, which is more than half the battle as a player. The other half is stopping the play.

Examining the Different Defenses

The next time you watch a football game, try this little experiment: Right before the offense snaps the ball, glance at the defense and note where the defensive players are on the field. Then very quickly ask yourself, “What defensive scheme is that?” If you do this for a whole game, you’ll start to understand — and appreciate — the different defensive strategies. You’ll see why the defense lines up differently, for example, when it’s making a goal-line stand or when it’s defending against a long pass. You’ll begin to see precisely what the defense is trying to do to stop the offense from gaining yards and scoring.

To help you recognize different defensive strategies, the following sections describe a handful of common lineups that defenses use to keep the offense in check.

4-3 front

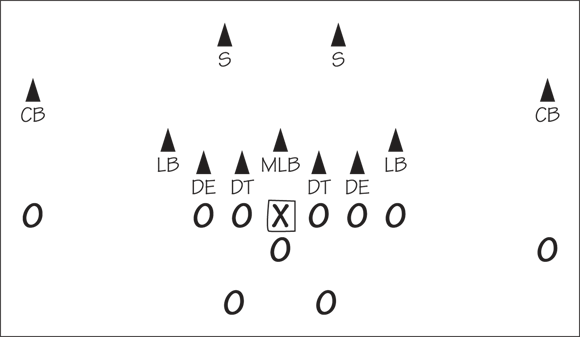

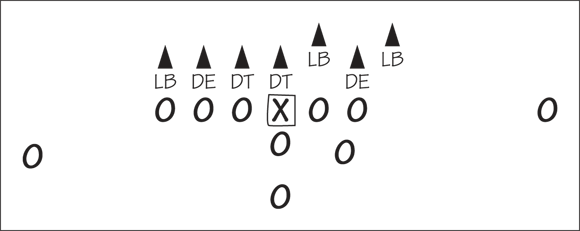

The majority of NFL teams use the 4-3 defense, which consists of two defensive tackles (DT), two defensive ends (DE), two outside linebackers (LB), a middle linebacker (MLB), two cornerbacks (CB), and two safeties (S), as shown in Figure 11-1. The 4-3 was devised in 1950 by New York Giants coach Steve Owen, who needed a fourth defensive back to stop the Cleveland Browns from completing long passes. Owen, whose cornerback was future Dallas Cowboys head coach Tom Landry, called the 4-3 his umbrella defense because the secondary opened in a dome shape as the linebackers retreated into pass coverage. In the first game in which the Giants used it, the defense clicked, and the Giants beat Cleveland 6-0, shutting out the Paul Brown-coached team for the first time in its history.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-1: The 4-3 defense consists of four linemen (DE and DT), three linebackers (LB and MLB), and four defensive backs (CB and S).

Although it was initially devised to stop the pass, the 4-3 defense should be able to stop both the pass and the run. The 4-3 was first widely used in the late 1950s, when Sam Huff became the Giants’ middle linebacker and the Detroit Lions, who also liked the scheme, made Joe Schmidt their middle linebacker. Both of these Hall of Fame players were instinctive and played run defense well because they were strong and exceptional at lateral pursuit of the ball carriers. But they also played the pass well. They could move away from the line of scrimmage (in other words, drop into coverage) and effectively defend a team’s short-passing game.

Although it was initially devised to stop the pass, the 4-3 defense should be able to stop both the pass and the run. The 4-3 was first widely used in the late 1950s, when Sam Huff became the Giants’ middle linebacker and the Detroit Lions, who also liked the scheme, made Joe Schmidt their middle linebacker. Both of these Hall of Fame players were instinctive and played run defense well because they were strong and exceptional at lateral pursuit of the ball carriers. But they also played the pass well. They could move away from the line of scrimmage (in other words, drop into coverage) and effectively defend a team’s short-passing game.

On paper, this defense is well-balanced. As with all defenses, having talented personnel is important. The 4-3 defense needs ends who are strong pass-rushers and physically tough against the run. The ideal middle linebacker is someone like former Chicago Bear Dick Butkus (see Chapter 19), who could single-handedly make defensive stops and possessed the all-around savvy to put his teammates in favorable positions. The defensive tackles should be strong against the run and agile enough to sustain pass-rush pressure on the quarterback.

In the 4-3, the stronger and more physical of the two outside linebackers lines up over the tight end, leaving the other, quicker outside linebacker to be more of a pass-rusher. With the exception of all-star teams, it’s almost impossible for a team to have superior players at every position. However, teams tend to use a 4-3 when they have four pretty good defensive linemen and a good middle linebacker. If three of those five players have all-star potential, this scheme should be successful.

Later in this chapter, I tell you about variations of the 4-3, including the Dallas 4-3, the over/under, and the Chicago Bears’ 46 defense of the mid-1980s. Some teams also use four-man lines but use more defensive backs rather than linebackers behind their four-man fronts.

3-4 front

Bud Wilkinson created the 3-4 defense at the University of Oklahoma in the late 1940s, but the 1972 Miami Dolphins, who went undefeated that year, were the first NFL team to begin using it in earnest. And the Dolphins did so out of necessity; they had only two healthy defensive linemen. Chuck Fairbanks, another Oklahoma coach, used the 3-4 as an every-down defense with the New England Patriots in 1974; also in 1974, Houston Oilers coach O. A. “Bum” Phillips did the same.

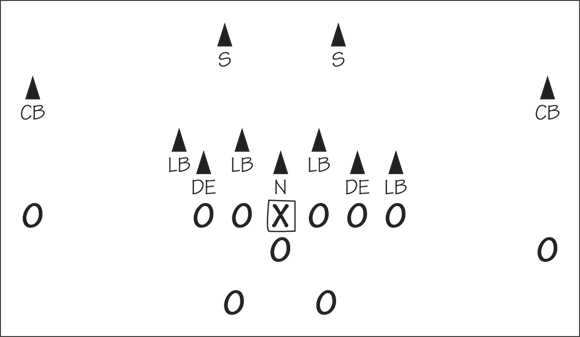

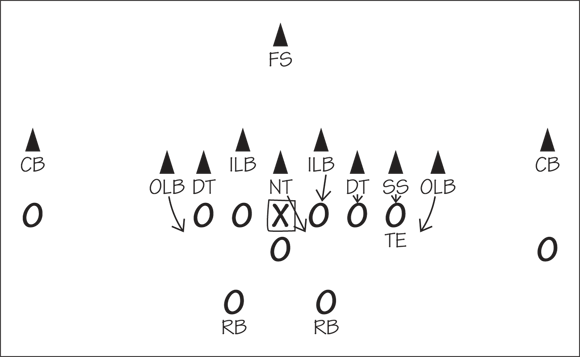

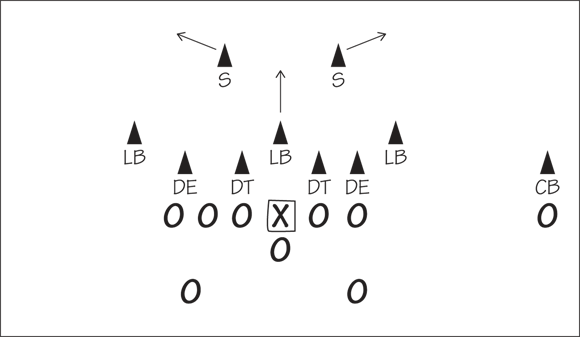

Unlike the 4-3 defense, the 3-4 defense uses only three defensive linemen, with the one in the middle called the nose tackle (N), as shown in Figure 11-2. The prototype nose tackle was the Oilers’ 265-pound Curley Culp, who combined strength with exceptional quickness; he was an NCAA wrestling champion. The 3-4 also employs four linebackers (LB), with the other two defensive linemen (DE) usually consisting of one superior pass-rusher and a rugged run-defender. In some 3-4 defenses, all three down linemen are two-gappers, meaning they plug the gap between two offensive linemen and aim to neutralize those two blockers, allowing the linebackers to go unblocked and make the majority of the tackles.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-2: The 3-4 defense lines up with three linemen (DE and N) and four linebackers (LB).

NFL teams in the 1970s adopted the 3-4 because they lacked quality defensive linemen and had more players who were suited to play outside linebacker. This is also true today in high school and college, where teams may lack quality defensive linemen but have no shortage of athletes who are capable of playing linebacker. The outside linebacker position fits an NFL player who’s at least 6 feet 3 inches, 240 pounds (the bigger and taller, the better). This player should have the ability to play the run and rush the passer like a defensive end.

The 3-4 can be a flexible defense. In some instances, the defense may decide to drop seven or eight players into pass coverage. Conversely, the interchangeable personnel of a 3-4 could end up sending three to five players to rush the quarterback. In the 1970s, Miami actually called its 3-4 defense “the 53” after linebacker Bob Matheson’s jersey number. Matheson moved around, but he was primarily a pass-rushing linebacker.

The 3-4 defense is ideally suited to defending multiple offensive formations, meaning a defensive coordinator can match his personnel with that of the offense. Also, the physically dominant nose tackle can prove to be a nightmare for the offensive center. The nose tackle can neutralize the center’s pass-blocking attempts by constantly shoving his strong head and shoulders to the ground or moving the center sideways, thus negating his effectiveness as a blocker.

The 3-4 defense also spawned the term two-gap style. With this technique, the defensive linemen and inside linebackers actually block the offensive linemen to either side, opening a lane for the untouched outside linebacker to make the play. The 3-4 defense focuses on the outside linebackers; in fact, they’re the stars of this defense.

The greatest defensive player I ever saw, Lawrence Taylor of the New York Giants, was essentially an outside linebacker in a 3-4 scheme. Although Taylor was great at sacking the quarterback in this scheme, the 3-4 defense generally is better at stopping the run than rushing the passer. And Taylor was exceptional at both aspects of the game — he could rush but also stand his ground and contain the run. Plus, he had the speed to pursue a running back moving away from him and still make the tackle.

The greatest defensive player I ever saw, Lawrence Taylor of the New York Giants, was essentially an outside linebacker in a 3-4 scheme. Although Taylor was great at sacking the quarterback in this scheme, the 3-4 defense generally is better at stopping the run than rushing the passer. And Taylor was exceptional at both aspects of the game — he could rush but also stand his ground and contain the run. Plus, he had the speed to pursue a running back moving away from him and still make the tackle.

The NFL in recent years has seen an increase in the number of teams using the 3-4 defense. The New England Patriots and Pittsburgh Steelers, who between them won five Super Bowls in the first decade of the 2000s, used the 3-4. But for the most part, NFL teams have shied away from the 3-4 defense because, to be successful, they need tall, 250-pound outside linebackers who also have speed. That kind of player is hard to come by.

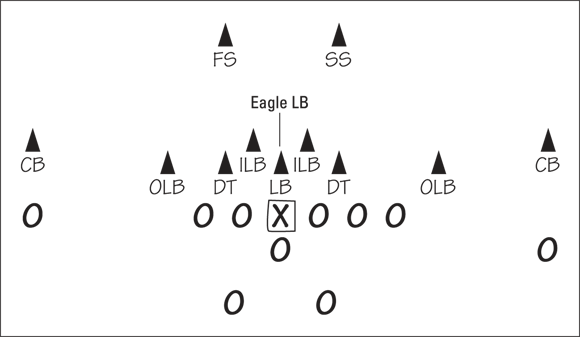

3-4 eagle

Fritz Shurmur started using the 3-4 eagle defense with the Los Angeles Rams in the late 1980s. Shurmur’s defense used another linebacker in the role of the nose tackle, as shown in Figure 11-3. Instead of having a 300-pound player over the center, Shurmur inserted a 240-pound linebacker, a player who was susceptible to the run because most offensive centers outweighed him by 60 pounds. To succeed against the run, this linebacker needed to use his quickness and guile to shoot offensive line gaps. However, this linebacker was a solid tackler and was also good at dropping into pass coverage. The remaining personnel were identical to a typical 3-4 scheme, so it was sometimes referred to as a 2-5 eagle because of the five linebackers.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-3: The 3-4 eagle defense uses a linebacker (LB) in place of the nose tackle.

Shurmur devised this defense to confront (and ideally confuse) San Francisco 49ers quarterback Joe Montana, who had an exceptional ability to read a defense correctly and complete a pass to the open man. Having a lighter and faster linebacker drop into passing lanes was a totally foreign concept to any quarterback, who was used to that player remaining along the line of scrimmage rather than roaming in the defensive backfield like a defensive back.

The 3-4 eagle evolved from Buddy Ryan’s 46 defense (described in detail later in this chapter), which is all about applying pass-rush pressure at the end of the offensive line. The eagle places a premium on above-average linebackers who can sack the quarterback by rushing around the last blocker at the end of the offensive line. Most pass-rushers in this scheme prefer to line up away from the outside shoulder of the man responsible for blocking them. Outside linebacker Kevin Greene, who collected 46 quarterback sacks in three seasons (1988-1990), was the star (and benefactor) on Shurmur’s Rams teams. Greene used his speed and exceptional strength for a 248-pounder to later lead the NFL in sacks twice (in 1994 and 1996). His 160 career sacks are the most ever by a linebacker.

The eagle is more successful with above-average cornerbacks who can play man-to-man defense, or man coverage. Man coverage complements the deep zone drops of two of the five linebackers. To me, it makes more sense to drop a 240-pound linebacker into pass coverage than to use a 310-pound nose tackle, which is what some zone blitz defenses do. That’s one of the big differences between these two defenses. This defense can be very effective against a team running the West Coast offense (see Chapter 8), especially one that has a versatile running back who can damage a defense with his receiving as well as his running ability. Linebackers are better suited to catching and tackling this kind of ball carrier, while also being capable of defending the tight end, who’s always an important performer in the West Coast offense.

Despite the lack of a big body over the center, the eagle 3-4 defense isn’t susceptible to the run because it employs two very physical inside linebackers and can bring a strong safety close to the line of scrimmage to serve as another tackler (or linebacker). This maneuver allows the eagle to put eight defensive players in the box, which is the area near the line of scrimmage where the defense is most effective at stopping the run. Some teams, however (particularly those with a good, versatile running back), have tremendous success running the football against this defense. Why? Because the offense is able to neutralize the light linebacker playing nose tackle and run the ball from formations from which it had always thrown the football. Such tactics confuse the defensive personnel, who are unable to predict what the offense intends to do.

Despite the lack of a big body over the center, the eagle 3-4 defense isn’t susceptible to the run because it employs two very physical inside linebackers and can bring a strong safety close to the line of scrimmage to serve as another tackler (or linebacker). This maneuver allows the eagle to put eight defensive players in the box, which is the area near the line of scrimmage where the defense is most effective at stopping the run. Some teams, however (particularly those with a good, versatile running back), have tremendous success running the football against this defense. Why? Because the offense is able to neutralize the light linebacker playing nose tackle and run the ball from formations from which it had always thrown the football. Such tactics confuse the defensive personnel, who are unable to predict what the offense intends to do.

Dallas 4-3

I want to make a distinction here: When Jimmy Johnson coached the Dallas Cowboys in Super Bowl XXVII and XXVIII, Dallas’s defense had an abundance of talented players among the front seven but didn’t have particularly speedy or skillful cornerbacks. The Dallas 4-3 defense used four down linemen and three linebackers but gambled more than Johnson would have allowed and occasionally used more of a nickel scheme, inserting another defensive back in place of a linebacker, as shown in Figure 11-4. This defense is predicated more on a team’s personnel than on a particular alignment.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-4: The Dallas 4-3 defense uses four linemen (DE and DT) but may use an extra defensive back in place of one of the three linebackers (OLB, MLB, and LB).

But what Dallas was able to accomplish, and what has been copied, was the scheme cover four or four across in the secondary. Because Dallas’s front seven was so talented and could apply extreme pressure on the quarterback, the secondary was able to play deeper and prevent the deep pass. Of course, this scheme puts extra pressure on the two cornerbacks, who are expected to be able to take the opposition’s two best receivers man-to-man and shut them down without any help.

In the Dallas 4-3 defense, the safeties also can creep up toward the line of scrimmage to provide support against running plays. Basically, this defense allows the safeties to cheat and overplay one aspect of the offense when they anticipate the play correctly. With the rest of the defense attempting to funnel almost every running play toward these physical safeties, the back goes down if the safeties make good reads. In modern football, in which teams may have physically gifted tight ends, the Dallas 4-3 defense puts the safety in a better position to defend the seam pass, the throw right down the hash marks to the tight end or to a receiver running straight upfield.

Flex

Coach Tom Landry invented the flex defense for the Dallas Cowboys teams of the 1970s and 1980s. It’s a 4-3 alignment, too, but it flexes (moves back) two defensive linemen (DT and DE) off the line of scrimmage by 2 or 3 yards, as shown in Figure 11-5. These two offset linemen read the blocking combinations of the offense and attempt to make the tackle (or the sack) while their teammates try to break down the offense’s blocking patterns.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-5: The flex defense puts two defensive linemen (DT and DE) 2 or 3 yards off the line of scrimmage.

The flex defense works only if you have talented defensive tackles. These flexed defensive linemen must have exceptional speed and the ability to react. By being a couple of yards off the line of scrimmage, they should be able to see how an offensive play is developing. But to be able to stop a play from their positions, they also must have the speed to recover the 2 yards while moving forward. Being off the line of scrimmage makes it more difficult for offensive linemen to block them. The blockers have to run a couple of yards to strike them, but meanwhile the defensive linemen are also moving, quite possibly in a different direction.

Bob Lilly (whom I tell you more about in Chapter 19) was one of the greatest defensive tackles of all time; Randy White (nicknamed The Manster because he was half man and half monster) was very close to him in ability. The keys to both players’ success were their exceptional quickness and strength. White was a converted linebacker playing defensive tackle; you don’t find many players capable of making that change. Shifting White’s defensive position was a bold move by Landry more than 30 years ago, but this defensive scheme wouldn’t work well today. The basic premise of the flex — to have defensive linemen reading — hinders the pass-rush. A player can’t be reading and waiting for something to come his way. Instead, he has to react and attack if he wants to tackle the quarterback. The flex seemed like a great defense against the run until Eric Dickerson of the Los Angeles Rams ran for 248 yards against it in a playoff game at the end of the 1985 season.

Bob Lilly (whom I tell you more about in Chapter 19) was one of the greatest defensive tackles of all time; Randy White (nicknamed The Manster because he was half man and half monster) was very close to him in ability. The keys to both players’ success were their exceptional quickness and strength. White was a converted linebacker playing defensive tackle; you don’t find many players capable of making that change. Shifting White’s defensive position was a bold move by Landry more than 30 years ago, but this defensive scheme wouldn’t work well today. The basic premise of the flex — to have defensive linemen reading — hinders the pass-rush. A player can’t be reading and waiting for something to come his way. Instead, he has to react and attack if he wants to tackle the quarterback. The flex seemed like a great defense against the run until Eric Dickerson of the Los Angeles Rams ran for 248 yards against it in a playoff game at the end of the 1985 season.

Zone blitz

Zone blitz sounds like a contradiction in terms: Teams that like to play zone pass coverage generally don’t blitz. Zones are safe; blitzes are all-out gambles. Dick LeBeau, a player and coach for 45 years in the NFL, is usually credited with inventing this defense in the late 1980s to take advantage of his huge safety, David Fulcher.

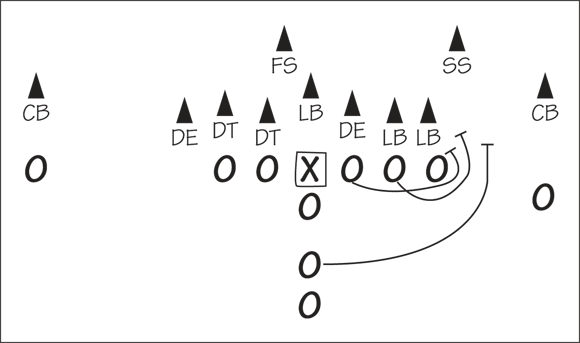

The Pittsburgh Steelers and the Carolina Panthers were the proponents of the exotic zone blitz in the mid-1990s (Figure 11-6 shows a zone blitz). From a base 3-4 alignment, they would overload one side of the offense by placing as many as three of the four linebackers to that side. They might stick a cornerback there, too, or put a safety there in place of a linebacker. The object was to confuse the quarterback and the offensive linemen, forcing them to wonder: How many people (four, five, or six) are really coming at the quarterback?

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-6: The defense lined up in a zone blitz.

The down linemen in this scheme usually engage the center and guards. Their intent is to occupy these players and give them the impression that they may be rushing the quarterback. Often, the defensive linemen merely hold their ground while waiting for the run, or they stop, peel back off the line of scrimmage (by 5 yards or so), and then attempt to cover that area (this move is referred to as short zone coverage) against a possible pass play. The object of a zone blitz is to create one or two free lanes to the quarterback for the linebackers or defensive backs who do the blitzing.

The zone blitz is an ideal defense against an inexperienced or gun-shy quarterback. The defense wants to get the quarterback thinking. Before any quarterback drops back to pass, he scans the secondary to try to figure out what kind of defense it’s playing. This is called reading the secondary. When a quarterback looks at a zone secondary, he doesn’t usually equate it with blitzing. But in this defense, the quarterback checks out the defensive front, too. He wants to have an idea where the blitz or the most pass-rush pressure will come from. A good quarterback believes that he can move away from the pressure from the suspected overloaded side and gain enough time to complete his pass.

The zone blitz is an ideal defense against an inexperienced or gun-shy quarterback. The defense wants to get the quarterback thinking. Before any quarterback drops back to pass, he scans the secondary to try to figure out what kind of defense it’s playing. This is called reading the secondary. When a quarterback looks at a zone secondary, he doesn’t usually equate it with blitzing. But in this defense, the quarterback checks out the defensive front, too. He wants to have an idea where the blitz or the most pass-rush pressure will come from. A good quarterback believes that he can move away from the pressure from the suspected overloaded side and gain enough time to complete his pass.

The combinations and varieties of zone blitzes are endless. However, offenses have discovered that a short pass play to the flat (outside the hash marks) may be effective against this defense. Most zone blitzing teams give offenses considerable open areas to one side or the other underneath their final line of pass defense. Often, blitzing teams send a player who normally would be in pass coverage toward the quarterback. When a defense blitzes like that, it always keeps two people deep because it doesn’t want to surrender a long touchdown.

46

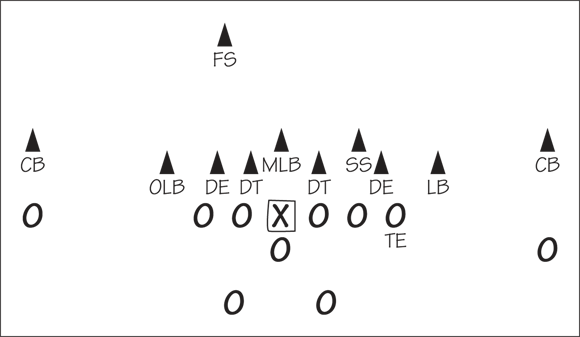

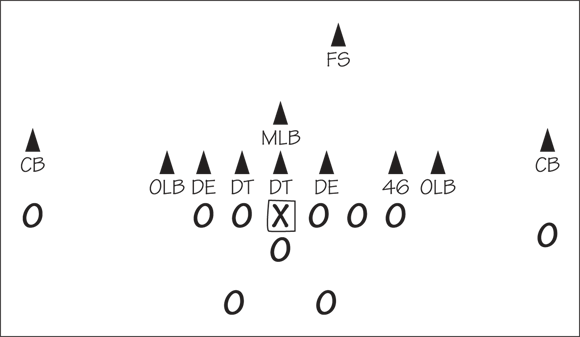

The team most often associated with the 46 defense is the Chicago Bears of the 1980s. The 46 didn’t receive its name from its alignment, but rather because Bears free safety Doug Plank wore jersey number 46 and often lined up as a linebacker. Buddy Ryan, the Bears’ defensive coordinator, altered Chicago’s original personnel in the 46 defense — five defensive linemen, one linebacker, and five defensive backs — to four defensive linemen, four linebackers, and three defensive backs, as shown in Figure 11-7. The fourth so-called linebacker, the “46,” is generally considered a cross between a linebacker and a strong safety.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-7: The Bears’ 46 defense used four down linemen (DE, DT), four linebackers (OLB, MLB, 46), and three defensive backs (CB, FS).

In the 46, three defensive linemen line up across from the offense’s center and two guards, making it impossible for those offensive players to double-team the defender opposite the center. In Chicago, this defensive player was Dan Hampton. When Ryan became head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles, the player over the center was Reggie White. Hall-of-Famers Hampton and White were the strongest linemen on their teams; they were also excellent pass-rushers. Their exceptional ability made it possible for them to collapse the offense’s pocket, thus ruining the quarterback’s protection. They were good enough to beat two blockers in their prime, paving the way for teammates to have a clean shot at the quarterback as White and Hampton occupied his protectors.

In the 46, three defensive linemen line up across from the offense’s center and two guards, making it impossible for those offensive players to double-team the defender opposite the center. In Chicago, this defensive player was Dan Hampton. When Ryan became head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles, the player over the center was Reggie White. Hall-of-Famers Hampton and White were the strongest linemen on their teams; they were also excellent pass-rushers. Their exceptional ability made it possible for them to collapse the offense’s pocket, thus ruining the quarterback’s protection. They were good enough to beat two blockers in their prime, paving the way for teammates to have a clean shot at the quarterback as White and Hampton occupied his protectors.

The Bears had sensational success with the 46 defense. In 1984, they recorded 72 quarterback sacks, and the following year, they allowed only ten points in three playoff games en route to their Super Bowl XX championship. In one six-game stretch, the defense scored 27 points and allowed 27 points. When the Bears won the Super Bowl, the defensive players carried Buddy Ryan off on their shoulders, while the offensive players took care of head coach Mike Ditka.

In the 46, no defender lines up over the two offensive tackles. Instead, defenders are placed off both of the offensive tackles’ outside shoulders. From there, their intentions are straightforward: rush and sack the quarterback.

The biggest downsides to the 46 defense are the pass-coverage limitations. Your cornerbacks are stuck in man-to-man coverage 90 percent of the time, with only one safety to help. You can drop an inside linebacker or two into zone coverage; however, when you line up with basically only three defensive backs on the field, often a linebacker gets stuck one-on-one with the tight end. If the tight end can run, this matchup may be a mismatch for the defense. Also, the 46 defense can struggle against a three-wide-receiver offense because of the man-coverage situations. But, the philosophy of this defense is to attack the quarterback before he can pick apart the secondary.

The 46 is a good defense against offenses with two-back sets. Why? Because such an offense doesn’t spread the 46; instead, it condenses it. And that’s perfect, because the 46 is an aggressive defense designed to attack. The two-back offense affords the 46 defense the opportunity to send its pass rushers off the corner. When they come off the corner, the edge of the offensive line, no one is there to impede their path into the backfield, where they can cause the most damage.

The 46 defense can have a soft spot if the offense believes it can run wide against it, particularly in the direction of one of the offensive tackles. If the offense can block the two outside defenders, pushing them outside, the runner can cut inside the offensive tackle and run through that lane. And when the cornerbacks drop deep, the back may be able to gain a lot of yards. In college football, offenses beat the 46 defense by having the quarterback run an option play. In the option, the quarterback starts running around the end. He can either turn upfield or lateral the ball to a running back. (Note that pro coaches don’t usually allow their quarterbacks to run an option play.)

The 46 defense can have a soft spot if the offense believes it can run wide against it, particularly in the direction of one of the offensive tackles. If the offense can block the two outside defenders, pushing them outside, the runner can cut inside the offensive tackle and run through that lane. And when the cornerbacks drop deep, the back may be able to gain a lot of yards. In college football, offenses beat the 46 defense by having the quarterback run an option play. In the option, the quarterback starts running around the end. He can either turn upfield or lateral the ball to a running back. (Note that pro coaches don’t usually allow their quarterbacks to run an option play.)

Over/under 4-3

The over/under 4-3 is basically a scheme with four down linemen and three linebackers — what I call a Sam linebacker on the tight end and then two inside linebackers. The object of this defense is to shift more defensive linemen to the offense’s suspected point of attack, which is called the over, or to shift the linemen to the weak side of the offensive formation, which is called the under. The down linemen are the stars of this show.

In the under 4-3, shown in Figure 11-8, one defensive lineman is on an offensive tackle, another is on the guard and center, and another is on the open side offensive tackle (the side opposite the tight end). In the over 4-3, three of the four defensive linemen shift toward the strong side of the offensive formation (the tight end side), as shown in Figure 11-9. A defender is always directly opposite the tight end in both of these defenses.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-8: The under 4-3 aligns on the weak side of the defense.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-9: The over 4-3 shifts the down linemen toward the offense’s strong side.

The over-and-under scheme gives the defense flexibility in the way it uses its players in the secondary. Tony Dungy, former coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Indianapolis Colts, used to bring his strong safety close to the line of scrimmage, and suddenly he had an eight-man front. For a change-up look, defenses can drop safeties to their traditional spots 12 yards off the line of scrimmage and roll the two cornerbacks up to or within 3 yards of the line of scrimmage, making the defense look like a nine-man front.

For this defense to succeed, a team needs talented people up front — players capable of dominating the line of scrimmage. This scheme works only if the down linemen are special players like Dungy had with Warren Sapp in Tampa Bay. This defense can survive with average linebackers, decent safeties, and good cornerbacks, but it must have hard-charging linemen who are physically capable of beating offensive linemen.

The over/under 4-3 was a perfect defense for Dungy. Unlike Dungy, some teams and their coaches are very impatient; they want to attack and be aggressive, maybe pushing the panic button and blitzing the opposition before the time is right. But a coach like Dungy was able to sit back. He wasn’t emotional. He folded his arms and let the offense keep the ball for seven or eight plays, believing that sooner or later the offense would panic and make a mistake. This defense can force an offense into making mistakes, too. Believe me when I say that some NFL offenses have trouble running eight plays without screwing something up.

Cover two (and Tampa two)

The cover two defense was devised to stop the West Coast offense, which relies on short passing routes and running backs coming out of the backfield to catch passes (for more about the West Coast offense, see Chapter 8). When running backs as well as tight ends and receivers all catch passes, how can the defense cover so many receivers?

The answer is the cover two, a 4-3 zone defense. Rather than cover receivers man to man, the defensive side of the field is divided into zones, with each zone the responsibility of a safety, cornerback, or linebacker. The deep part of the field (the area starting about 15 yards from the line of scrimmage) is divided into two large zones, each of which is the responsibility of a safety. (The cover two gets its name from these two large zones.) The safeties guard against receivers running downfield to catch long passes. Meanwhile, the area between the line of scrimmage and the deep part of the field is divided into five small zones, each of which is the responsibility of a cornerback or linebacker. The idea is to stop the short pass, or if a receiver succeeds in catching a short pass, to keep him from gaining more than a few yards. If a receiver breaks a tackle and gets downfield, one of the two safeties for which the defense is named is supposed to stop the receiver from breaking off a long gain. The cover two defense requires talented linemen who can pressure the quarterback into throwing the ball before receivers can break into the open areas between zones.

The cover two, designed to stop short passes, is susceptible to a strong running attack. What’s more, the area in the middle of the field beyond 10 or 15 yards from the line of scrimmage is vulnerable because it falls between the two major zones. A speedy receiver who slips into this area and catches a pass can torch a team playing the cover two defense.

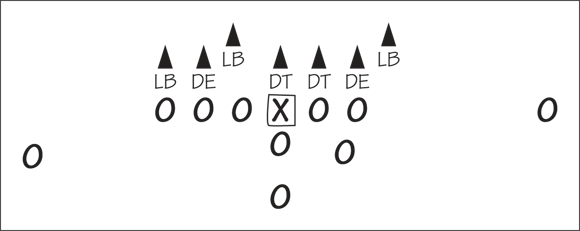

To protect the middle of the field, the Tampa two, a variation on the cover two, was invented. In the Tampa two, the middle linebacker drops back into the defensive secondary to protect against the pass, as shown in Figure 11-10. The Tampa two gets its name from the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, who used this defense starting in the mid-1990s under defensive coordinator Monte Kiffin. Running the Tampa two defense requires a stellar middle linebacker, somebody like Derrick Brooks, who played for the Buccaneers. Brooks had the speed to drop back and cover receivers as well as the strength and stamina to guard against runs up the middle. Most middle linebackers aren’t blessed with that combination of speed and strength.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-10: In the Tampa two, a variation of the cover two, the middle linebacker (LB) drops back into pass coverage.

Tackling Tricky Situations

Defenses are under constant pressure in every game: one mistake (a missed tackle in the open field or a blown assignment, for example) and the opponent has points on the board. The sections that follow tackle a couple of the tricky situations that defenses face and give advice for handling them.

Stopping a superstar

When playing against a superstar, whether he’s a running back or a quarterback, the defense must decide what facet of the offense it wants to focus on. In other words, the defense says, “I’m stopping Maurice Jones-Drew (who actually just retired, so just an example) and forcing the quarterback to throw the ball to beat me.” Defenses can’t do both — stop the run and the pass — against great offensive teams.

A team with a great safety, such as Troy Polamalu, can move its safety closer to the line of scrimmage without sacrificing its ability to cover receivers. The safety becomes another linebacker, the eighth man in the box. In other words, you have four defensive linemen and three linebackers, and you bring an extra run defender out of the secondary. If your safety reacts poorly, the defense can be susceptible to being beaten consistently by the pass. The consolation, though, is that the running back isn’t going to run for 150 yards.

Defenders must at least attempt to tackle a great back like Jones-Drew. They should never stand around and wait for a good shot; they should fly at him. If they miss, they miss, but they’re definitely not going to bring him down if they don’t at least give it a shot.

Defenders must at least attempt to tackle a great back like Jones-Drew. They should never stand around and wait for a good shot; they should fly at him. If they miss, they miss, but they’re definitely not going to bring him down if they don’t at least give it a shot.

Stopping the two-point conversion

The two-point play can make or break a game — and ultimately a season. (Check out Chapter 8 for more details on the two-point conversion.) On a two-point conversion attempt, teams try to spread the defense and then run some kind of pick pass pattern. Here’s how that pattern starts: The offense aligns two receivers on one side of the formation. The outside receiver runs toward the middle of the field, while the inside receiver runs, stops, and then heads in the direction of the outside receiver. When the two receivers cross, that’s called a pick play because the inside receiver tries to rub the man guarding him against the defender who’s covering his teammate. The desired result is an open receiver in the flat, the area beyond the defensive linemen but in front of the secondary.

In an effort to prevent the pick play, defenses trying to prevent two-point conversions are playing more and more zone coverage in the secondary. After all, they just can’t stop all the combinations of different pass routes, especially when offenses use a three-wide-receiver set. And the pick play is particularly successful against man-to-man coverage. So in trying to prevent a two-point play, the defense anticipates that most teams won’t run. Most offenses line up in a one-back formation with three receivers to one side.

The key to defending against a two-point conversion attempt is not to blitz. Instead, the defense should use a four-man line and play a zone defense behind it. You can play as many as six or seven defensive backs across because the defense doesn’t have to worry about the depth of the field. (After all, the end zone is only 10 yards deep.)

The key to defending against a two-point conversion attempt is not to blitz. Instead, the defense should use a four-man line and play a zone defense behind it. You can play as many as six or seven defensive backs across because the defense doesn’t have to worry about the depth of the field. (After all, the end zone is only 10 yards deep.)

Stuffing short yardage

The first thing you have to realize in short-yardage situations (third down and 1 yard or fourth down and 1 yard or less) is that you can’t stop everything. So you have to prepare your defensive front people — the defensive line and the linebackers — to stop one or two particular plays. Usually, you have eight defenders on the line, a combination of linemen and linebackers, and defensive players over both tight ends. The key play that you have to be able to stop is the offense’s isolation play.

An isolation play is what happens on a blast play, when a fullback runs inside to block a defensive player standing by himself before the quarterback hands off the ball to the running back behind him. The running play is called the blast play, but it works because the fullback isolates a specific defensive player. On this type of play, the defensive linemen must establish positive gap control.

Here’s what I mean: In addition to lining up across from an offensive lineman and defeating his block, each defensive lineman must get his body into a gap, either by stunting (when the defensive linemen jump to one side or the other, confusing the offensive linemen) or by lining up on the shoulder of an offensive lineman and securing the gap. Next, someone on defense must get some penetration across the line of scrimmage in order to have any chance of disrupting the play. ( Remember: Offensive linemen have trouble blocking quicker players who are charging straight ahead into a gap.)