Explosive Calisthenics, Superhuman Power, Maximum Speed and Agility, Plus Combat-Ready Reflexes--Using Bodyweight-Only Methods (2015)

2

EXPLOSIVE TRAINING

FIVE KEY PRINCIPLES

When I last left jail, I took a look around to see how athletes were training to build explosive power and strength. What I found was—to be honest—a real mess. Many of the traditional calisthenics methods which have been used for centuries to build power and total-body agility—the kind of methods drawn from classical martial arts, for example—had fallen by the wayside. Instead, folks were using modern gimmicks like cones, elastic bands and other devices.

What makes matters worse is that only a tiny, tiny percentage of folks who work out train for explosiveness anyway; and those athletes who do train for speed, power and agility tend to do it as an afterthought—because they need these qualities for football, combat, or another sport that requires them. Sadly, most folks who hit the gym don’t even train for speed/power at all! They have been taught to build their training around bodybuilding movements, performed with external weights and machines. Because these techniques are performed with a slow, smooth speed, and by isolating muscles (or groups of muscles) they actually de-condition the muscles and nervous system from moving quickly, or in an integrated manner. Yeah, you heard me—most modern, in-gym training is making people slower! If you think about it, you’ll know what I’m saying is true.

Combined with the epidemic of obesity, there’s no doubt about it—modern Americans are the slowest, least agile members of our species in history.

It doesn’t have to be this way. You can teach your body to be the lightning-fast, explosive, acrobatic, super-hunter your DNA is coded to make you. In this book, I’m going to teach you a system for developing speed, power and agility. Because of my background, this system is based on a handful of unbeatable principles:

· Use bodyweight

· Go Spartan

· Apply total-body training

· Focus on a small group of exercises

· Be progressive

Let’s look at each of these five principles, briefly.

USE BODYWEIGHT

Why are pure, traditional, bodyweight methods so important? Despite what you may think, I do not emphasize traditional bodyweight arts because I spent most of my career training in a cell, devoid of equipment. I emphasize them because they are the superior method of physical development—in all cases.

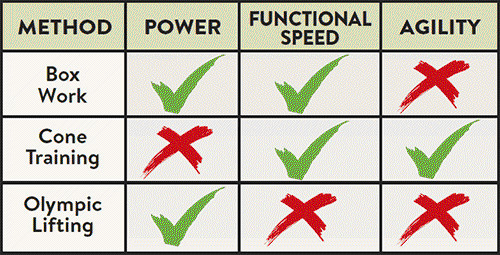

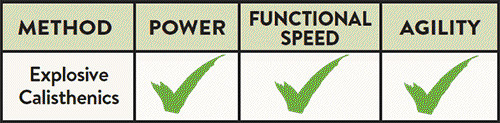

Take explosiveness. An athlete cannot be classed as an explosive athlete unless he (or she) possesses the three qualities I mentioned in the first chapter—power, functional speed, and agility—to a very high degree. Yet very few methods used today are capable of generating these qualities together.

Let’s look at three major modern methods, and compare them to calisthenics explosives (like flips, muscle-ups and kip-ups). The three methods most commonly seen today are:

· Box work (i.e., plyometric box jumps or box pushups)

· Cone training (i.e., zig-zagging around cones in a sports field or hall)

· Olympic lifting (i.e., the so-called “fast” lifts like snatches, cleans, jerks)

To see if these methods build the three qualities needed for our definition of an explosive athlete, we need to ask three questions, based on the definitions I laid out in the previous chapter:

— POWER: Does the athlete need to move with strength and speed?

— FUNCTIONAL SPEED: Is the entire body moved, quickly?

— AGILITY: Does the body have to change direction at high velocity?

Check out the table above. These questions should make it pretty clear that none of the three methods builds complete explosiveness:

· Box work (plyometrics) builds power because a load is moved quickly; it also builds functional speed because the entire body is moved. But box work does little for agility, since the majority of techniques are just variations on the athlete going up and down—there is no change of the body’s angle, which is essential for real agility.

· Cone training builds agility because the body is forced to radically alter its direction at high velocity; it also builds functional speed, because the entire body is moving rapidly. But since the load demands are fairly low—not much different from running—it cannot build power. (One of the reasons why cone drills are popular in schools is because of the low load demands—these exercises are pretty safe, and anybody can participate, no matter how weak they are.)

· Olympic lifting builds power, because it requires high strength used as quickly as possible. But there is no true agility required, because the body doesn’t appreciably change its direction—the weight just goes up and down. Also, the feet remain on the floor—or very close to it—during Olympic lifts, therefore the criteria of functional speed (rapid total-body movement) is not fulfilled. The body doesn’t move very far at all.

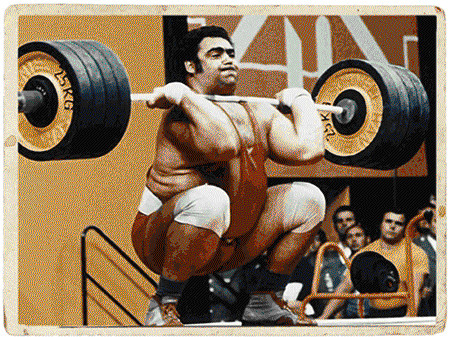

Vasily Alekseyev—the greatest Olympic lifter of all time. Awesome power, but about as much agility as a dump truck.

If you understood what I meant in the first chapter, it will be clear to you now that none of these three methods build complete explosiveness.

Now, compare these three with calisthenics explosive methods: kip-ups, front flips, back flips and muscle-ups—the four skill-based movement-types in this manual.*

*The first two movement-types—power jumps and power pushups—should be seen as a form of basic training/conditioning, to be approached before the four movement-types which follow them. I discuss this training hierarchy more on page 272.

These exercises win hands-down, since they all require a load (the body’s mass) to be moved quickly—power. They also require the entire body to be moved rapidly—functional speed. Finally, the agility criterion is also met perfectly because the body must change its direction at high velocity. This is very obviously true for flips and kip-ups, where the body must fire in different directions to lift off, rotate and land; but it is also true for the muscle-up—the initial “kipping” movement requires the body to quickly alter directions. (See page 212 for more information on kipping.)

Remember that these definitions are my own—power, functional speed and agility are fairly standard criteria for what comprises “explosiveness” in an athlete, but you can develop your own approach if you wish. I’m just showing you the way I think, and how I train my athletes.

Also, please understand that I’m not putting any of these other methods—weight-lifting, etc.—down. Each may be valuable in its own field—for example, box jumps teach basic power, strength athletes can certainly benefit from the Olympic work, and the cone stuff is useful in specialist sports like soccer. But if an athlete wants to become as explosive as possible—and possess the three qualities of explosiveness—each of these methods is lacking. The traditional calisthenics approach is not. I’m also not saying that these methods are negative or counter-productive.

GO SPARTAN

As well as being the most efficient means of explosive training, traditional bodyweight-only methods are also the most convenient. They are low or zero-tech—meaning they require no unusual equipment. At most, the “Explosive Six” drills in this book require you to have access to a floor, a wall, and a horizontal bar for hanging.

If they expect to learn explosive flips, for example, in a modern club, beginners are given rubber bands to help them with muscle-ups; gymnasts use foam rubber mats and blocks, and wedges and supports and cables and all kinds of similar devices. I understand why modern coaches lean on this stuff—for insurance purposes. It projects a powerful illusion of safety. (And it is an illusion. You can break your neck training on a foam mat, just the same as you can on grass, if you are not training with discipline.)

If you’re new to bodyweight training, and are worried that you’ll need a gymnastics club or a ton of commercial equipment to able to safely learn power feats like flips, kip-ups and muscle-ups, I would remind you of a truth: a thousand generations of our ancestors mastered these techniques—and perfectly—a thousand years before Christ. Certainly, well before any of this junk was even thought of. In my opinion, they’re worse than useless. These toys only get in the way. Avoid them.

Training Spartan also means training solo. This is something that is very important to me. I’ve had some incredible instructors throughout my training career, but I’ve more or less trained alone. For me, the effort and discipline in solitude is a spiritual aspect of my training. That’s why none of the drills in this book demand a spotter, or partner for assistance. Not one. That’s not the way gymnastics is typically taught, today. But this book is not about gymnastics—it’s about progressive calisthenics. The two are different.

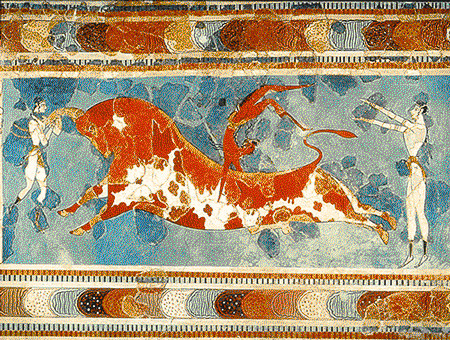

Ancient Minoan athletes built enormous explosive power (not to mention life-saving reaction speed) by flipping forwards over charging bulls. No ropes, no mats, no foam wedges—just the athlete, an angry, hurtling bovine, and the stony ground. It was dangerous, but can you imagine the levels of concentration and focus it built? Think about it next time you are complaining that you can’t afford gym membership.

British calisthenics training in the 1930s already included formal “spotting” drills—here, to assist with a back handspring. Rest assured, the master of progressive calisthenics does not require assistance.

I don’t care if you live in your parents’ basement, or if you are in a small military encampment in Afghanistan. Find something to hang from, and you have everything you need to become a master of explosive calisthenics.

APPLY TOTAL-BODY TRAINING

In the real world, you never need just a quick arm, or a quick foot. Some folks talk about boxers having “fast hands” but this is a misnomer; in reality, a boxing punch involves the entire body, the legs, waist, torso, shoulders and arms. Everything needs to be fast, or there is no speed. The same is true for kicking—ask any martial artist with “fast feet” and they’ll tell you the waist and upper-body are just as important in generating speed.

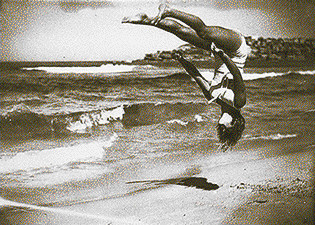

An athlete in the middle of a back flip variant. It looks effortless, but trust me—every muscle in the body is playing its part!

The brutal realities of the real world also tell us we need a fast body, rather than a fast body part. In combat, in military exercises, in sports, you gotta move your whole body. You know this is true. It’s no good having super-fast fingers from playing Xbox if those fingers are attached to a rusted up ton of crap. You can skip those specialist “speed” exercises some athletes love, like flipping and catching cards, or quickly grapping coins flipped off the elbow. There’s no carry-over. Skills like these—or even juggling, which some boxers used to do—are too specialized. They will not give you speed in any other area.

The best way to train for explosive power and speed is to pick only those exercises which work the entire body. You need to work as many muscles as possible to get the biggest bang for your buck. Sure, in this manual I advise some exercises which seem to work some body parts much more than others—clap pushups might seem to work the upper-body, pogo jumps might seem to work the lower legs—but as you advance beyond basic conditioning you’ll find that the exercise chains in this book work your entire body as a unit: the power pushups lead to advanced exercises which also involve the legs, and the jump series quickly recruits the arms and waist to add power. The same is true for all the movements in here.

Total body exercises also have the benefit of building integrated power. The body is a true gestalt entity—the total is more than the sum of its parts. An athlete who tried to work each body area (in isolation) for power could never be as fast or fluid as the athlete who trained these areas to work as a team. If you are familiar with hardcore strength training you’ll understand full well that the strongest men and women in the world are the ones who train their bodies with exercises which work everything at once, so they can maximize their system’s potential. Training for power and speed is no different.

FOCUS ON A SMALL GROUP OF EXERCISES

This principle follows on from the last one. If you are focusing on exercises which to some degree work the entire body, you don’t need to do very many of them—it’d be a waste of time, you’d be needlessly repeating yourself.

If you really want to build monstrous power, speed and agility in the shortest space of time possible, I advise you to stick to only a handful of movement-types which you get better and better at in a measurable way (this is progression, and it’s the principle up next). Since even total body exercises work the body in slightly different ways, I advise my students to pick a handful of classic calisthenics/acrobatic movements to cover all bases. Don’t waste your time with inferior exercises—go for the BIG movements which require maximum athleticism!

I personally feel that for the ultimate in hardcore explosiveness training, six movements are ideal:

· A jump - to teach posture, explosive leaping, tucking skills and landing

· An explosive pushup - to condition the arms and shoulders for high velocity movements, to improve upper-limb reflexes

· A kip-up - to build high levels of speed/power in the waist and to develop basic agility

· A front rotation - to teach the body to revolve forward at optimal speed

· A back rotation - to teach the body to revolve backwards at optimal speed

· An up-and-over - to teach the body to pull itself upwards with maximum power and skill

(I’ll break these six types of movement down a little more in the next chapter.)

Of course, you can tinker with the number “six”. You might prefer to work with four movements, or seven. (Some athletes will want to add side-rotations, or twisting movements. I personally think it’s safer and easier to add lateral and twisting movements after the athlete gains some basic proficiency.*) Just remember that anything less than six movements and some key speed-power skill gets missed; anything more than this and you risk overkill and loss of focus.

Of course, you can tinker with the number “six”. You might prefer to work with four movements, or maybe seven. (Some athletes will want to add side-rotations, or twisting movements. I personally think it’s safer and easier to add lateral and twisting movements after the athlete gains some basic proficiency.*) Just remember that anything less than six movements and some key speed-power skill gets missed; anything more than this and you risk overkill and loss of focus.

BE PROGRESSIVE

Finally, we reach the essence of true calisthenics—the principle of progression!

Again, this principle follows on from the last one. If you are working with a handful of movements, it’s no good doing the same old techniques over and over, again and again. Your goal (over time, as you gain power) should be to progress to harder and harder variations of those movements. Otherwise, how the hell will you know that you’re getting better?

An old school pike back flip.

The question is—how do I make explosive movements progressive? Part II of this book will give you all the keys you need to understand this area of training, but we’ll briefly look at one example now. Let’s take backwards rotation as an example. If you are working on becoming very explosive in backwards rotation, there is one coveted expert technique you’ll need to eventually master—the back flip. In a true back flip, you stand on solid ground and jump up, rotating backwards 360 degrees to land on your feet in exactly the same spot a fraction later. (Your hands help you swing but you don’t touch the floor with them at any time.)

*See round-offs (page 166) and cartwheels (page 167).

If you asked most out-of-shape people if they could learn a difficult bodyweight skill like the back flip, most would answer no—they’d see it as an impossibility. In one sense, they’d be correct—attempting this technique in one “mouthful” would indeed be impossible. However, if they broke the backflip into a series of stages—beginning with very easy techniques and moving to harder efforts—they could, in fact, learn this movement. In reality, I could teach pretty much any deconditioned individual how to perform a back flip using this method. This is the essence of progression; techniques which lead to more difficult versions of an exercise are called progressions. (Easier versions of a specific technique are called regressions.)

If an athlete is new to calisthenics, they must begin with some basic bridging exercises to mobilize and strengthen their spine, shoulders and limbs. Once they’ve benefited from those basics, the progressions can begin. We start with simple, easy backward rolls. Who can’t perform a basic roll? As you get used to rolling, you move to a more advanced variation; rolling using the hands. By now, your brain, spine and joints will be used to rotating, so we move to kick-overs from a bridge position:

Bridge kick-over: a progression to back flips.

Once these become second nature, you move on to variations of the monkey flip—an easy spin/flip which allows you to learn to rotate backwards by approaching the movement side-on. There are several progressions of the monkey flip, and by the time you get to the final one, you’ll be ready for the back handspring, where you jump and rotate over on your hands. After spending some time training with handsprings, you can explore some transitional exercises which finally lead you through to the back flip.

Like anything which seems impossible, the key to victory is to take things step-by-step. Bear in mind that you are not meant to just try each progression, then race to the next one if you can do it—that would just lead to failure. At the heart of this method is learning to love each progression—master and milk it for all its worth. You don’t become a better athlete by moving up through the progressions you can’t do very well. You become a better athlete by taking the time to practice the progressions you can do well.

LIGHTS OUT!

A vanishing percentage of people who work out ever even attempt to unlock their body’s inherent power and speed. That’s nuts. In the real world, these qualities are the pinnacle of athleticism and survival ability! And yet, folks stick to the same old slow training, or boring cardio on machines.

Almost none of this tragic negligence has to do with the body. It’s all down to attitude. Psychology. How many people who train avoid incredible feats like the back flip because, in their mind, they are impossible? Too many trainees are of the opinion that there are just “some people” who are naturally gymnastic, and these are the kind of people who go on to learn these feats—it’s beyond the safe reach of the average Joe or Jane. I’ve spoken to athletes who thought they were “too old” to learn explosives, or “too weak”, or “too heavy”, or whatever. These athletes don’t understand that their bodies are fully capable of performing incredible feats of power—they just need to be programmed the right way: using the five principles in this chapter. As soon as these self-doubting trainees see and begin to understand the progressions I’ve included in the following pages, something “clicks” within them...and they realize that they too can achieve the elite, super-impressive explosive moves in this book.

And so can you!