Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

Swimming the Thames: Then and Now

‘The Thames has never really been considered a friend of the swimmer. But it is more than the danger of pollution that acts as a deterrent. It is some deep fear of its nature that seems to prevent its use’

Peter Ackroyd, Thames: Sacred River, 2008

The story of Thames swimming is an ongoing one; there is no particular date at which it started and as long as the Thames still exists there is no reason for it to end. Instead, barring a major catastrophe such as the floods of early 2014, it will become even more popular. Because wild swimming is back; in rivers and in the sea, in lakes and ponds, we have rediscovered the joys of swimming outdoors. Today there are open-water clubs, books, blogs and magazines all devoted to swimming outside, and if Peter Ackroyd was right when he wrote in 2008 that ‘some deep fear of its nature’ prevents us from using the Thames, then this has certainly changed.

Back in 1867 Charles Steedman felt driven to write a manual on outdoor swimming in order to provide tips and advice; now we have bestselling guides to wild swimming spots across the country. When Archibald Sinclair commented in 1885 that ‘open-water bathing has not been encouraged so much … as it ought to be’, he attributed this to the Baths and Washhouses Act that gave people indoor places to bathe, just as in the 1960s and 1970s when another surge in the construction of public indoor baths helped to drive us away from the river. But to Sinclair, as to all ‘wild’ swimmers, a plunge in the open is something to be remembered, ‘the body glows all over … the spirits become light and elastic’.

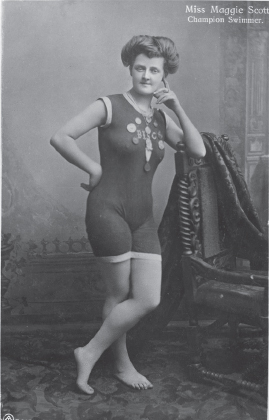

A picture postcard of Maggie Scott, one of many champion swimmers from the early 1900s.

Some people started swimming in the Thames when they were children - and their parents and grandparents before them - and continue to do so, others have only turned to the river in the past few years and now they can’t keep away from it. They describe the thrill of seeing life from water level, of being part of nature; they’re surprised at how clean it is, they enjoy the wildlife, the current and the tide. In the past ten years or so, after decades of avoiding the place, we have come back to the Thames in numbers not seen for a long time.

We might have lost the old pontoons, pools, lidos and bathing islands that once lined the river, due to finances, Health & Safety, fears of pollution, and a preference for warm indoor pools. But although we don’t compete in the Thames like we used to, there are now mass-participation events at the very river spots that fell into decline during the Second World War and were largely abandoned in the 1960s, at Windsor, Eton, Henley, Maidenhead, Chiswick and the London Docks. Access to the river has become harder in many places, but people still swim alone and with families, and are just as likely to form small informal groups, while every year at least 10,000 people sign up for organised swims in the Thames.

In some cases the tradition remains virtually unbroken: the Otter Swimming Club, formed in 1869, still races in the Thames. In other cases we’ve come full circle, resurrecting traditions we didn’t know we once had, like open-water swimming clubs in Henley, Maidenhead and Chalkwell, and plans for a new floating bath in central London.

While the history of once famous swimmers has been buried over time, modern swimmers are replicating what their forebears did, even if they’ve never heard of them, and going much further. In July 1878 Agnes Beckwith swam twenty miles from Westminster to Richmond and back to Mortlake, dressed in an amber suit and a jaunty little straw hat. In 1916, Eileen Lee swam thirty-six miles, in modern times Alison Streeter has set two Thames records downstream and up, while in 2013 Ness Knight became the first woman to swim the non-tidal Thames, completing 155 miles.

It’s a similar story when it comes to male swimmers; in 1876 Frederick Cavill swam twenty miles, Captain Webb topped that with forty and in 1908 Montague Holbein managed fifty. Now new records have been set by Kevin Murphy, Lewis Pugh and Charlie Wittmack, while Andy Nation has swum further along the Thames than anyone else. In 1925 Norman Derham swam across the estuary, while nearly eighty years later it was the turn of Peter Rae and Wouter Van Staden. In the summer of 2014 Lewis Pugh was back in the Thames again, this time as the final leg of his Seven Seas swim to highlight the need for protected areas in the world’s oceans. He swam forty miles upstream from Southend to the Thames Barrier, having already completed swims in the Adriatic, Aegean, Black, Red and Arabian seas. He then delivered a petition to Prime Minister David Cameron.

There have been regulations about Thames swimming since Victorian times, along with warnings about strong currents and tides, the depth and the cold, pollution and boats. ‘No swimming’ signs remain, while the latest form of legislation is the by-law introduced in 2012 which prevents swimming through central London. But London Mayor Boris Johnson, who once jumped in at Chiswick - ‘it was lovely and cool … and didn’t do me any harm’ - argues that if people want to swim in the Thames ‘then they should be allowed to indulge their preferences in peace’. In February 2014 he approved a £40,000 feasibility study ‘scoping for a major new initiative on the River Thames - a London Lido’.

There have, however, been major differences in the way we swim the waterway. The first is clothing and equipment, particularly the wetsuit, which has changed significantly since the modern version was invented in 1952. Once river bathers went naked, then people were made to cover up with drawers, tunics and pantaloons, followed by hand-knitted one-piece costumes which women had to keep covered until they entered the water. Now we have ‘fastskin’ racing suits, high-tech goggles, fins, neoprene gloves and boots. Wetsuits keep us warmer, able to swim throughout the year and more buoyant in case something goes wrong. They have made us faster and capable, perhaps, of doing longer distances, and their popularity is mainly due to the rise in the triathlon, now recognised as an Olympic sport, while open-water swimming was added to the Olympics in 2008.

For some the swim is initially the most challenging part of a triathlon, and then they find it’s their favourite and just keep going. Arguments remain over whether open-water swimmers should have to wear wetsuits in organised events, but with equipment comes sponsorship, and now mass swims have a host of sponsors, from wetsuit brands to drinks and food manufacturers. Detailed entry forms asks participants what sort of wetsuit and goggles they wear,what drinks product they use for training, racing or recovery, and what they eat beforehand. Athletes no longer swim in the Thames, like Captain Webb, sustained by alcohol, or like Agnes Beckwith on beef tea; instead there is a whole array of sports supplements, energy gels and bars, and numerous books and articles on diet.

Swimming may no longer be seen as the new art form it was in Victorian times, but it is regarded as an ever-improving science. There are classes for those who want to swim outdoors for the first time, swim studios, coaching sessions for triathletes who want to better their stroke and speed. Perhaps those like Shaw Method instructor Phil Tibenham, who loves to swim near Grafton Lock, are our new professors of swimming, using the principles of the Alexander Technique to teach ‘greater body awareness’, just as Victorian manuals once gave us hand-drawn illustrations on strokes and techniques.

The growth in mass-participation events means swimming in the Thames has become a business, but balance this with the fact many people swim to raise money. And this is the second biggest difference when it comes to swimming the Thames, that a lot of us do it for charity. A decade ago few charities offered swims as a way to fundraise; now most do, in lakes, the sea, indoor pool swimathons and, of course, the Thames. People use Facebook to link up with others, post intended swims, join in events and share experiences and, unlike most social media users, people then meet up in real life - with one joint purpose, to swim.

We are far less likely to drown in the Thames now, because in general compared to 150 years ago more of us can swim. When Agnes Beckwith started her Thames swimming career, around 3,000 people drowned every year in England and Wales. In 2012, twenty-six people died while swimming in the UK, according to the National Water Safety Forum, including four in a river. The number of people who drowned while angling, however, is similar (twenty-four), while ten people died in a bath, Jacuzzi or hot tub. When Victorian teenager Emily Parker raced the Thames and Annie Luker dived from bridges, most of those working on the river didn’t know how to swim, whether lightermen or sailors, and for years swimming professors and the press urged for better and cheaper ways for people to learn. Yet today many of the nation’s lidos have closed and the teaching of swimming, as a way to save your own life and somebody else’s, has fallen by the wayside. In the 1870s it was seen as a key life skill for men and boys, and then eventually for everyone. Now increasing numbers of children don’t know how to swim because they receive little or no instruction at school, and few are taught how to dive because most diving boards have been removed. So while fatalities are down, drowning is still the third most common cause of accidental death (along with fire and smoke) among children under the age of fifteen in England, after transport and asphyxia. Swimming might be included in the national curriculum, but a third of children can’t even cover 25 metres by the time they leave primary school, according to the ASA. This means their lives are at risk and they’re not able to really enjoy the water, whether indoors or outside.

By the 1920s women bathers no longer had to cover up at the seaside but could wear the sort of one-piece costume advocated by Annette Kellerman in 1907 when she was arrested on an American beach for indecency.

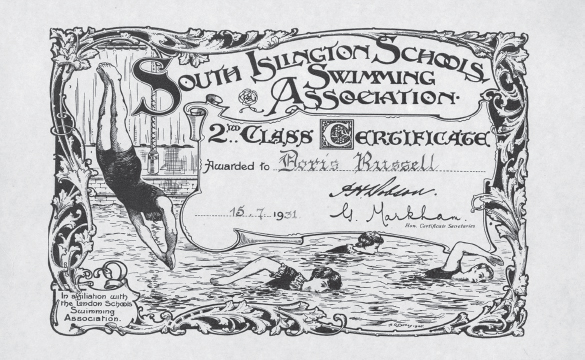

A school swimming certificate from 1931. Today a third of children can’t swim 25 metres by the time they leave primary school.

As for the future of organised Thames swimming, many look forward to the day when open-water swimming has its own governing body, just like British Triathlon. At the end of 2013, at a meeting convened by H2Open magazine, safety at open-water events was a major concern. ‘Open-water swimming is growing fast,’ says editor Simon Griffiths. ‘The biggest events now attract several thousand swimmers, but that growth has led some to question the direction the sport is taking and whether an organisation needs to oversee the development of open-water swimming clubs and to provide guidelines for event organisers.’ Unlike triathlon, where organisers can ask the British Triathlon Federation to sanction their events, nothing similar exists for swimming.

Simon believes the development of clubs is essential to the sustainability of the sport. He launched H2Open after ‘I’d been doing triathlons for a few years and really liked the open water component. Then, around 2009, I saw the Great Swim Series was taking off. Lots of people swim and not just in triathlons, and there was no magazine for them. I could see a gap in the market. If you’re not experienced then you want a controlled, managed environment and some recognition at the end like a medal. There is a fear about open water and what’s underneath you. Swimming for anyone under fifty is what you do in heated pools, but there’s been a reawakening of interest in open-water swims. We are warned against the Thames and open water, more so than we need to be.’

There are times, however, such as the heavy flooding in late 2013 and early 2014 when England and Wales suffered the wettest winter since records began, when we’re right to be cautious. Thousands of homes were damaged and the sewage network was overwhelmed by floodwater. ‘It’s sink or swim in the flooded Thames Riviera,’ read a headline in the Telegraph, swans were seen swimming over a football pitch in Windsor, two people used a gondola to travel through a flooded village square in Berkshire. The advice from the National Health Service began with ‘never swim in fast-flowing water’.

But as the floods receded, the swimmers returned. Because nothing has ever quite stopped us from swimming the Thames, not bad weather or war, not pollution or legislation.

Of the three swims I’ve done, the upper Thames, the Millwall Dock and the Thames Estuary, it would be hard to choose which was best because each offered a different way of experiencing the river, its water, landscape and history. Now I’ve decided an annual Thames swim will be my treat to myself and next year I’ll go to Marlow where villagers once bathed before breakfast and where Jerome K. Jerome wrote parts of Three Men in a Boat.

As long as the Thames still flows through England there will always be new challenges to meet - who can swim downstream, upstream, across and along, who can swim the furthest, who will be the youngest, the oldest? The glorious story of swimming the Thames has only just begun; it has always been, and always will be, a swimmer’s friend.