Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

18

London Bridge

‘The agile Agnes all proclaim

The lady champion aquatic,

And warm admirers hold her fame

To equal that of heroes Attic’

‘An ode to Agnes Beckwith’, in Fun, 1879

I am standing on the north side of London Bridge, looking downstream towards the Tower of London, where Tower Bridge looks like a gateway to a medieval castle moored in the middle of the river. Everywhere are boats, from City cruisers to HMS Belfast, while a row of buoys bob in the water like swollen orange lozenges. There have been several bridges spanning this section of the river reaching back to Roman times, and when the Victorian stone-arched bridge opened in 1831 it became the busiest and one of the most congested points in London. By the mid-nineteenth century 100,000 people walked across it every day - an ideal spot then if you intended to swim from it and wanted a crowd. In September 1875 it was here that Agnes Beckwith plunged into the Thames from a rowing boat and sped all the way to Greenwich. She was just fourteen years old.

It was Agnes Beckwith who first sparked my interest in Thames swimming. I initially came across her in a British Library poster, an advertisement for a performance at the Royal Aquarium in 1885. She stands dead centre, wearing a satin costume, stockings and boots, one arm resting casually on a beach rock. Just behind her in the water a man has both arms raised in the air, his mouth open in alarm; presumably in the process of drowning. Then I read a passing reference to a swim she had done in the Thames, with no idea what a trailblazer she had been. Here she was diving off a rowing boat in 1875 when most sailors couldn’t swim and when 3,199 people had drowned by accident that year in England and Wales, 500 of whom were women.

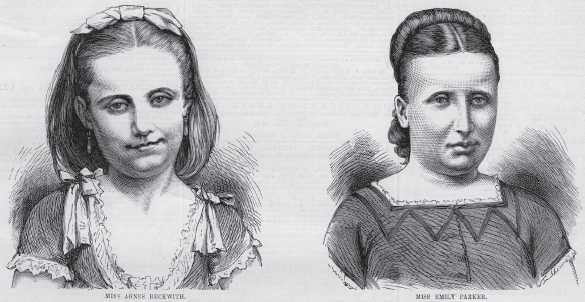

Agnes Beckwith and Emily Parker, both aged fourteen, were set to race each other in the Thames from London Bridge to Greenwich in September 1875.

Thanks to Captain Webb’s crossing of the Channel the month before, long-distance events were the height of popularity and it was now that Thames swimming really came into its own. Swimming of any kind was in fashion: ‘while the present weather lasts all England by sea and stream will take a periodical if not a daily plunge into the limpid element,’ reported the Penny Illustrated Paper. It was ‘the mania of the hour, and a very good mania too,’ commented The Graphic. But few could match the skill and strength of Agnes Beckwith.

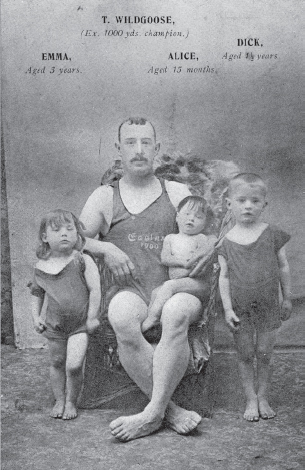

Born in 1861, she’d been swimming and performing since she was a few years old. Her father was swimming professor Frederick Beckwith of the Lambeth Baths, who’d spent several months training Webb for his Channel swim. In 1854 he’d been declared ‘English professional champion’, a title he held for six years, and had been connected with the Baths for nearly a quarter of a century. Frederick’s ‘family of frogs’ started giving public displays in the early 1860s and in 1865 he included Agnes, introducing her as a two-year-old, although she was probably older. By the time she was nine she was performing with her brother Willie, himself a champion swimmer, as ‘Les Enfants Poissons’ in a plate-glass aquarium at the Porcherons Music Hall in Paris.

T. Wildgoose and children, a swimming family similar to that of Frederick Beckwith’s ‘family of frogs’.

Frederick, like most swimming professors, was a lover of spectacle and a savvy promoter, issuing swimming wagers at indoor pools as early as the 1850s, and organising fêtes of natation. His daughter’s swim in the Thames was both a publicity stunt and a money-making scheme. Just weeks earlier another professor by the name of Parker had advertised that his sister Emily would swim five miles from London Bridge to Greenwich. He’d placed a wager of £50 to £30; Emily had started training, her brother had even fixed a date. But Professor Beckwith got there first. On 1 September, just before 5 p.m., Agnes, ‘of slim make, and diminutive stature’, took to the Thames and ‘at once commenced a rapid side-stroke, which she maintained to the finish’, blowing ‘kisses to spectators on the way’. The Morning Post reported, ‘Swimming Feat by a Female’, and noted that her time was ‘remarkably fast’. The object was to ‘decide a wager of £80 to £40 laid against her by Mr Baylis, the money being deposited with Bell’s Life’ a weekly sporting paper: ‘the event created a great deal of excitement … a perfect swarm of boats accompanied, and indeed impeded, the swimmer the entire distance.’

Like Annette Kellerman some thirty years later, it was Beckwith’s attire that was of just as much interest, ‘a swimming costume of light rose pink llama trimmed with white braid and lace of same colour’, and no future press report would be complete without reference to her clothing. At Horseferry Dock a salute was fired, and she was ‘encouraged with lusty cheers’. Passing Millwall, she ‘crossed to the north side and took advantage of the strong tide. At this point she was met by the saloon steamer Victoria, whose passengers were vociferous in their applause.’ She arrived at Greenwich Pier to ‘the spirited strains of “See, the Conquering Hero Comes!”’. She then swam ‘some distance beyond the pier’ before being taken on board a boat, having accomplished the distance in one hour seven minutes and ending ‘almost as fresh as when she started, and to all appearance was capable of going considerably further’. She had also ‘declined’ the offer of brandy and port wine and therefore accomplished her swim with ‘no stimulant whatsoever’.

Was it her idea or her father’s to swim the Thames? What did she think about as she made her way down the river, and what were her mother’s views on the matter? We’ll probably never know, because there remain many gaps in the story of Agnes Beckwith. While university sports lecturers Dave Day and Keith Myerscough have recently uncovered a great deal, she remains largely unheard of, even in the world of swimming.

Her achievement would have been astonishing. No woman had ever done what she did in the Thames, and only one man. Byron might have boasted of his swim in 1807, but that was only three miles. In 1826 the party of printers had covered four and a half miles, the Eton Psychrolutes were swimming the Thames a couple of decades later, but they were ex-public school boys, and of course the aristocratic jockeys were getting away with naked races. In terms of truly organised events the one-mile amateur championship for men had only begun in 1869, while the Lords and Commons five-mile race wouldn’t start until a couple of years later, and it would be another decade before the Amateur Swimming Association was formed. No one had succeeded in a Thames swim of this distance, except Webb the year before when he completed ‘nearly six miles’, watched by just three people.

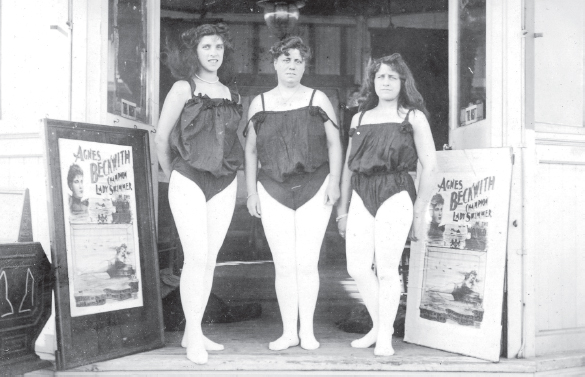

The following year Agnes Beckwith swam three-quarters of a mile in the River Tyne, and then ten miles from Battersea Bridge to Greenwich. Once again hundreds assembled to watch when, on 5 July 1876, she reached Greenwich after two hours and forty-three minutes. ‘Ladies who would learn to swim, take lessons of Miss Beckwith!’ reported one paper. But it then added disparagingly, ‘Miss Agnes, now you have given such ample proofs that you are a duck of a girl, stick to your proper vocation - that of teaching your sex to swim.’ Beckwith did just that, forming her own ‘talented troupe of lady swimmers’, and in the coming years she taught many women to swim, with her pupils giving benefit shows.

She also returned to the Thames. In July 1878 her twenty-mile swim from Westminster to Richmond and back to Mortlake received huge press coverage. One journalist applauded ‘little Missie Beckwith’s marvellous swim … What girl will now remain ignorant of swimming?’ Press reports frequently mentioned her ‘ease and grace’ and she was nicknamed ‘the Lambeth Naiad’. The Era reported that ‘an immense number of spectators thronged’ Westminster Bridge and the Thames Embankment, and ‘accompanied’ by the steamer Matrimony, gaily ‘decorated with flags, and attended on by her father and redoubtable brother William in a skiff, the youthful water sprite, dressed in a closely-fitting amber suit, adorned with white lace, a jaunty little straw-hat, and fluttering blue ribbons, parted the waters and commenced her tedious journey at twenty-six minutes past twelve o’clock’.

‘The Lambeth Naiad’. Agnes Beckwith was a trailblazer in terms of Thames swimming, but is yet to be inducted into any hall of fame.

At Coates’s boathouse she was ‘fired at by way of encouragement, which, no doubt, was very comforting, and was certainly greatly appreciated by those on board the steamer, who cheered lustily, and probably took the compliment to themselves’. She ‘received an ovation as she glided prettily under Barnes-bridge that must have been highly gratifying’, the ‘merry young siren’ then ‘shot under Old Kew-bridge, laughing and keeping up an animated conversation with her friends’. An enormous crowd welcomed her at Richmond as she ‘floated under the picturesque bridge’ where she ‘went through numerous elegant evolutions in the water that were greatly applauded’. It was then back to Mortlake where she was greeted with the sort of enthusiasm ‘this young water-queen so unquestionably deserved’. She completed the swim in six hours twenty minutes, and it was only at Kew Bridge, after eleven miles, that she had paused to take a cup of beef tea.

The swim was preparation for an attempt on the Channel, an ambition she had stated in the press, which would again have been unheard of for a woman and wasn’t attempted until nearly a quarter of a century later by Madame von Isacescu. But it appears this was too expensive for her father to finance, although he was now advertising her as ‘Heroine of the Thames and Tyne’.

Like other professional swimming performers, Agnes Beckwith travelled the country giving exhibitions at seaside regattas and indoor pools. In July 1880 she spent thirty hours treading water at the Royal Aquarium, equalling a record set by Webb, in what was known as the whale tank - it had recently been home to a beluga whale which had died apparently because of mistreatment. She ate all her meals in the water and read the day’s news reports on her swim. A few months later Beckwith stayed 100 hours in the tank and once this was done she remained at the Aquarium teaching ‘ladies how they may save themselves and others from drowning … every afternoon and evening [she] shows the fair sex how to master the water, and swim and dive and float as dexterously as a Mermaid’. The Princess of Wales came to watch, bringing her children along, which meant Frederick could now promote his daughter as being ‘patronized by the Royal Family’.

Agnes Beckwith (in the middle) travelled the country giving exhibition shows with her ‘troupe of lady swimmers’.

In 1882 Beckwith was being billed as ‘the premier lady swimmer of the world’ at a farewell benefit at the Aquarium, before she set off for a tour of the United States where the New York Times commented, ‘unlike most female performers, Miss Beckwith is pretty’. She swam in France and Belgium, and in 1887 took part in P.T. Barnum’s Greatest Show on Earth at Madison Square Garden. The same year the Princess of Wales took her daughters to the swimming annexe of the Westminster Aquarium to let Beckwith ‘inspire them with a love for the delightful art’.

Her impact on the world of swimming, as with her successors Annette Kellerman and Mercedes Gleitze, was enormous, but there has been no induction into any hall of fame for Agnes Beckwith. Yet her 1875 Thames swim was still well known nearly forty years later. In his 1914 book Swimming, Montague Holbein cites her in his chapter entitled ‘Long-distance Swimmers and their Feats’. First comes Lord Byron, then Dr Beadale of Manchester, J.B. Johnson, Boyton, Webb, and Cavill, then finally Agnes Beckwith whose five-mile swim, according to Holbein, was for a wager of £100.

In 1916, when Eileen Lee swam thirty-six miles from Teddington, the British press still remembered Beckwith. She was the ‘pioneer of long distance swimming for ladies’ and her twenty-mile swim in 1878 had stood as a record until Lee beat it. The Australian press remembered her, too; an article in 1911 on ‘LADY SWIMMERS SOME AMAZING FEATS’ by the Adelaide Advertiser opens with: ‘There must be people still living who looked on with amazement, one day in 1875, as Miss Agnes Beckwith stepped out of the water at Greenwich “fresh as paint” after swimming from London bridge.’ It then quotes ‘sporting baronet’ the late Sir John Astley: ‘If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes I shouldn’t have believed it was possible … After this I quite believe that the day will come when women will beat men in the water, whatever they do on land. I shall not live to see the day, but it will come.’ The Advertiser then names Beckwith’s rivals, Emily Parker, Lizzie Gillespie and Annie Johnson, and comments, ‘the woman of today, where she has not improved on these performances, has proved a worthy successor of these pioneer mermaids’. The paper goes on to cite Ethel Littlewood, Lily Smith, Claire Parlett, Vera Neave (who, in 1914, was the ‘best distance swimmer the world has seen’), Olive Carson and Mme Isacesen, before turning its attention to their own Annette Kellerman. So, while the British and Australian press once placed Agnes Beckwith firmly where she belonged, as the first woman to swim a notable distance in the Thames, who has heard of her today and how many of these other women are household names?

Just like Kellerman, Agnes Beckwith also had firm views on women and swimming, telling the press it was the ‘best exercise’, developed the figure ‘to a marvellous degree’, and improved ‘the chest and arms wonderfully’. It promoted circulation and gave a healthy appetite, and for those who wanted ‘to cultivate pure muscle’ the overhand method was best. ‘One of its little known advantages,’ she said, ‘lies in its being a preventive of rheumatism, and I don’t know any swimmer who is troubled with that malady. It is also quite invaluable as a cold cure.’ Again like Kellerman, she also linked swimming with weight: ‘strangely enough, swimming has a fattening effect, and many of us find a difficulty in keeping down flesh.’

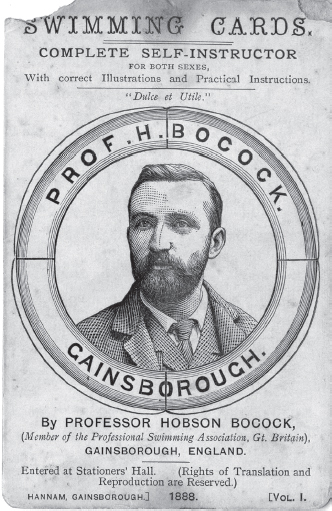

Swimming professor Hobson Bocock whose 1888 ‘self instruction’ swimming cards were aimed at ‘both sexes’ thanks to pioneers such as Agnes Beckwith.

By now the press was urging that all girls and women should know how to swim; ‘no girl’s education should be considered complete before she is able to swim well,’ declared the Penny Illustrated Paper. In 1899, for ‘one night only!’, Beckwith performed at the new Lambeth Baths as ‘Champion Lady Swimmer of the World’. She was still holding exhibitions as well as teaching in the early 1900s. By now she had married theatrical agent William Taylor, their son was born in 1903 and five years later he was performing alongside his mother as ‘the youngest swimmer in the world’. She performed for visitors to the Industrial Exhibition in Manchester in 1910, but a year later was calling herself an ex-professional swimmer.

What happened to Agnes Beckwith after this remained a mystery for a long time, and it took sports lecturer Dave Day and his partner Margaret ten years to establish when and where she died. Dave’s original interest came through researching Frederick Beckwith, whose biography he wrote for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. It was only very recently that he was able to update Agnes’ entry. After her first husband died she married again and then, widowed for a second time, she moved in with her son, William. In 1948 the family sailed for South Africa and settled in Port Elizabeth. Agnes Beckwith died at the age of ninety at Nazareth House, a care home run by Nazarene nuns, in 1951. She was buried in the South End cemetery, where her name appears on a memorial plaque listing patients cared for by the nuns. To Dave, it was her career that helped to ‘pave the way for the British women who represented their country’ in the 1912 Olympics.

Sports lecturer Keith Myerscough, meanwhile, first came across Agnes while researching the Blackpool Tower’s Aquatic and Variety Circus. ‘A programme for 1895 revealed an astonishing scene of swimmers conducting acrobatics in the water!’ he says. ‘I was hooked. Agnes Beckwith was a true pioneer of swimming for females. She alone was responsible for making swimming in public a respectable activity. Her amazing feats were the equal of most male swimmers, which gave her a mythical aura that legitimised swimming as a profession. Countless working-class females escaped the factories to earn a living in an activity - synchronised swimming - that would eventually become a sport.’

Emily Parker, meanwhile, whom Beckwith had beaten to her intended swim from London Bridge to Greenwich, also completed some major Thames swims. She was said to be just a few months older than Beckwith when in September 1875 she also set off from London Bridge, this time to Blackwall. Like Beckwith, she was a professional swimmer who had performed in many English towns, and again like Beckwith she had a brother, Harry, who was ‘the champion of London’. The press reported that her appearances were made under his tuition.

At five o’clock on Saturday afternoon a river steamer ‘conveyed the heroine of the evening’ to London Bridge. Parker, ‘dressed in appropriate costume, descended into a wherry with her brother and her pilot. At once the boat shot out into the stream, and having passed under the bridge … amid much cheering, which Miss Parker gracefully acknowledged, the young swimmer plunged quietly into the Thames.’ The river police kept the Thames free from the obstruction of seventy or eighty wherries ‘as well as they were able’, while Harry stood in the accompanying boat ‘with all his natatory honours thick upon him’.

Parker used a ‘vigorous breast stroke’ and never showed ‘the slightest sign of fatigue’. River pistols, guns and small cannon were fired from various points as she made her progress down the Thames, and ‘sailors in the ships cheered as the swimmer and the river mob which followed went past’. Just before seven she arrived opposite Greenwich Pier, where several thousands were waiting along the Embankment hoping to catch sight of her, but had to ‘content themselves with cheering while the black patch on the water rapidly drifted in the gathering twilight towards Blackwall’.

In the ‘half obscured light of the moon’ Parker reached Blackwall Pier and was taken on board the steamer in a ‘most vivacious mood’. Her time was one hour thirty-seven minutes. She had successfully eclipsed Beckwith’s swim from London Bridge to Greenwich ‘by going a stage further’. But, once again, the press were not entirely supportive. ‘While we admire the endurance and skill of these young ladies,’ commented The Graphic, ‘we hardly like young ladies indulging in this public exhibition of their natatory abilities.’

Both young women were making a name for themselves, outdoors in the River Thames where everyone could see them, easily swimming five - even twenty - miles, and in conventional terms not wearing much in the way of clothing. No wonder the press were a little unnerved. But if male journalists didn’t like to see young ladies indulging in public exhibition, others did, and how exciting it must have been to watch teenagers Agnes Beckwith and Emily Parker in the middle of the ‘greatest metropolis in the world’ swimming their hearts out.

The same month that Parker reached Blackwall Pier, she also swam from London Bridge to North Woolwich Gardens, using her ‘favourite chest stroke’ and covering around ten and a quarter miles. The Morning Post reported the tide was ‘moderately good, but the wind, which was rather high, was dead against the swimmer, and the water very rough and lumpy’. At Greenwich ‘a man named Buike, who had accompanied little Emily from London Bridge, gave up’. From Blackwall Pier to Woolwich ‘the water was extremely rough, and the constant breaking of the waves in the face of the swimmer distressed her considerably’. At this point her brother Harry entered the water ‘with a view to encourage his sister, who was working hard’.

When Parker arrived at her destination she got on to a boat and her brother then carried her up to the gardens. ‘After she had partaken of some refreshment’ - having not had ‘any stimulant whatever while she was in the water’ - she was presented with a gold medal valued at ten guineas.

Other noted Victorian swimmers also set off from London Bridge, among them Frederick Cavill, who attempted to swim to Gravesend in July 1876. The ex-Champion of the South Coast would ‘start a little swim’ said the press, intended as a ‘gentle preparation’ for a projected Channel crossing. Cavill, born in 1839 in London, had joined the navy, and seen action, before taking up professional swimming. In 1862 he’d won the English 500 yards swimmingchampionship. This time he swam ‘over twenty miles from London Bridge to Greenhithe, the longest distance to that time on the Thames’, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography. But Cavill failed to reach Gravesend because ‘the ebb tide had run out’ and he could ‘make no head way’. There was no mention in any press reports of what he was wearing. The following month he swam from Southampton to Southsea Pier and from Dover to Ramsgate, before trying the Channel, but he was forced to give up three miles from the end.

Described as having a ‘robust constitution, broad chest, and great muscular power’, he tried the Channel again - and failed again - in 1877. He then migrated to Australia, settling in Sydney and establishing himself as a swimming professor, publishing a pamphlet, How to Learn to Swim, and successfully completing a number of long-distance swims. He must have also returned to England for in 1897 it was Cavill who won the Kew to Putney race, beating twenty-one other competitors. The British press described him as Australian, ‘a wonderfully good man’ who had now won ‘his first success in England’. Cavill died in 1927. One of his sons, Arthur, was a professional champion of Australia and is credited with originating the crawl stroke, while another, Sydney, is said by some to be the originator of the butterfly stroke.

Meanwhile, other famous sporting men decided that, rather than swimming from London Bridge, they would dive from it. In 1871, J.B. Johnson made ‘a sensational leap’ in order to rescue a drowning man, a ‘Mr Peters of the West-end’. But rumours abounded: was ‘Mr Peters’ none other than Johnson’s brother, Peter, himself a professional swimmer? It appeared that ‘his fall from a steamer’ and his successful rescue were pre-arranged and the press concluded the whole thing was ‘a got-up affair’. It might have been daring, but it hadn’t been heroic. The brothers declined to comment. In 1872 Johnson became the first person ever recorded to try and swim the Channel, and although he failed it was his attempt that inspired Webb. He went on to compete in many Thames races, such as the Putney to Hammersmith championships, and was immortalised in a ballad:

Oh ! J.B. Johnson, I wish that I were him,

Oh ! J.B. Johnson, he is the man to swim,

And hasn’t he the pluck? he floats just like a duck,

I wish that I could swim, like J.B. Johnson.

Johnson’s title the ‘Hero of London Bridge’ was short-lived, but others were quick to copy him. One Monday afternoon a man named Rawlins, whiling away his time in a local tavern, bet his friends a pot of beer that he would jump from London Bridge. He got on to the parapet and ‘dived head foremost into the Thames’. The bridge was crowded with pedestrians and ‘the excitement was intense’ as Rawlins came to the surface and began swimming towards Old Swan steamboat pier. Several ‘watermen, who thought it was an attempt at suicide’, rowed after him. A captain from the London Steam-Boat Company threw out a rope and Rawlins, who was ‘a first class swimmer’, got on to the steamer. The police went after him, but he’d already made his escape.

A few years later, on 27 September 1889, it was seventeen-year-old Marie Finney’s turn to dive when The Graphic reported, ‘A LADY’S LEAP FROM LONDON BRIDGE’. ‘Of course the act was an illegal one, and on that account the arrangements for the performance were kept secret. Beyond the customary gangs of loafers, no one was about at the time. It was decided that Miss Finney should leap from the first arch on the Middlesex side at 2.45 … A number of steamboats and tugs were passing at the time, and it was not until three o’clock that the signal was given to the fair diver. The course, so to speak, being clear, one male friend took her broad-brimmed hat, and another her long ulster, the lady immediately leaping on to the coping-stone. She was attired in a tight-fitting, dark blue navy jersey.

When Marie Finney dived from London Bridge in 1889, diving was still a new sport in England. By 1903 the Highgate Men’s Pond on Hampstead Heath (above) was hosting high diving displays and Graceful Diving Championships.

‘After pausing for a few seconds to take her bearings, she dropped upon the projecting stone, a couple of feet below the parapet, and then dived down, striking the water beautifully. The whole business occupied only a few moments, and before the loafers could realise what had happened she was striking out for the boat. On reaching it she waved her hand to her friends, and was rowed to the shore none the worse for her immersion.’

Other reports added that just before she jumped a nearby policeman, busy regulating the traffic, was oblivious to what was going to happen, and that it was her brother who gave the all-clear signal from below, after which she was ‘hoisted’ on to the bridge. Presumably the press had been tipped off about the stunt beforehand. And what a stunt it was: diving was still a relatively new art form in England, and the country’s first professional purpose-built diving stage wouldn’t appear for another four years, at the Highgate Men’s Pond on Hampstead Heath which hosted the national Graceful Diving Championships. In the early nineteenth century diving had been more of a plunge and the aim was to dive in and go as far as possible underwater. Then in the 1890s Swedish and German gymnasts developed it into an art form until a dive meant the actual process of entering the water. The Swedes also brought in the swan or swallow dive, far more graceful than the ‘English header’, and fancy diving, adding more complex somersaults and twists. It would be another five years before Annie Luker dived from London Bridge and went on to perform at the Royal Aquarium, where her husband was too nervous to watch her; the Amateur Diving Association wasn’t formed until 1901; diving for men didn’t become an Olympic sport until 1904, and for women not until 1912. So Finney’s ‘leap’ from London Bridge would have been the first time many people had seen a dive at all.

Born in Southport in 1872, Finney’s brother James was a champion swimming professor and together they had been giving aquatic entertainments ‘in a glass bath’. She was, said the Penny Illustrated Paper, a ‘captivating young lady, as lissome as a mermaid under water’ and, unlike Johnson’s dive, there was ‘no pretence of a rescue on the part of Miss Finney, who proved herself an exceedingly courageous damsel … this daring little Lancashire witch walked from a neighbouring hostelry on to London bridge … to all appearances out for a stroll’.

The following spring Finney wasn’t so lucky. This time she was in Dublin and attempting to dive from O’Connell’s Bridge into the River Liffey. ‘Thousands of people assembled, but just as Miss Finney was clambering along the battlements, previous to taking the dive, she was seized by a policeman and arrested.’ She was charged with obstructing the thoroughfare and fined £1.

But she went on to complete other dives, often off seaside piers, and together with her brother toured the United States giving exhibitions at theatres.

A few weeks after Finney’s 1889 leap from London Bridge, another famous diver followed suit. Tom Burns’ plan was to walk from his home city of Liverpool to London and back, diving from a bridge at each end of the journey.

‘The Champion Diver of the World’, as he would be known, first dived from Runcorn Bridge, and then swam eighteen miles along the Mersey to Liverpool, before setting off to London. When he reached London Bridge ‘the police had to be evaded, while no little difficulty was found in procuring a recess from which to jump off. At length however, Burns saw an opportunity. The boatman below gave the signal, and in a few seconds Burns doffed his clothes, mounted the bridge and dropped on to the parapet. After a careful survey, with a loud shout he plunged.’ Burns then swam the overarm stroke, and pulled himself into the boat, while ‘hundreds of people watched him from the bridge and remained in earnest conversation all the time [he] was dressing in mid stream’. Then he started off on his journey home.

Born around 1867, Burns was a popular entertainer who amazed audiences at the Royal Aquarium where he dived 100 feet into a shallow tank of water. He’d learned to swim when he was nine, became a club captain and a swimming teacher, and won hundreds of awards for diving, swimming, running, walking and boxing, as well as numerous medals and awards for saving forty-two people from drowning. Seven years after his London Bridge dive, he is said to have dived from at least seven other London bridges. He also dived off bridges in Glasgow and Dublin, and was known for disguising himself as a ‘farmer, miner, newsboy, old woman, and a female market worker’ in order to evade police. However, he didn’t always succeed and was sometimes arrested after a dive. He died at the age of thirty, after a dive went wrong in North Wales where 3,000 people had gathered to watch. The Liverpool Echo applauded his ‘dare-devil exploits’ and described him as an erratic genius: ‘He had all the rough material in his composition out of which heroes are made.’

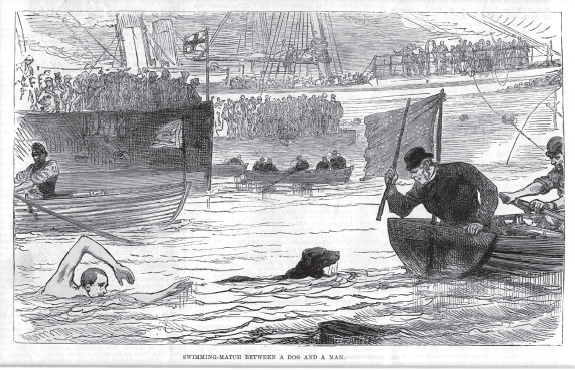

A six-year-old retriever named Now Then outpaces R. Smith from Sheerness in a ten-mile swim from London Bridge in August 1880. The dog lasted two hours, the man forty-seven minutes.

London Bridge wasn’t just the site for daring swims and dives, but, like Westminster Bridge, it was a place for novelty feats as well. In August 1880, for a wager of £50, R. Smith from Sheerness, a ‘known aquatic performer’, and a six-year-old black retriever named Now Then, said to have rescued seven people, set off to swim ten miles from London Bridge to North Woolwich Gardens. A newspaper illustration from the time shows the river full of boats, the dog calmly leading the way being spurred on by a slightly threatening looking bowler-hatted man in a rowing boat waving a stick. Smith started the race in front but was quickly overtaken and by the time he got to the Tower he was 50 yards behind. He gave up, ‘much distressed’, just off Limehouse after forty-seven minutes, while the dog continued to Deptford Creek ‘none the worse for wear’ after nearly two hours in the water. Of all the ground-breaking swims and dives from London Bridge, and particularly the women’s, few are celebrated today. Instead it is this novelty race between a man and a dog that is more likely to be referenced in books about the Thames.