Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

16

Westminster

‘Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!’

William Wordsworth, ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge’, 1802

Westminster Bridge is one of the most recognisable spots in London, towered over by Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament and long romanticised by painters and poets. ‘What sight in the world can be finer,’ asked George Henry Birch in his 1903 study of the Thames, ‘than that from the bridge at Westminster as we stand close to the statue of that Boadicea who in the far-gone days burnt this Roman City of Londinium?’

The original bridge was opened in 1750; today’s version is a modest looking construction painted pale green, the same colour as the seating in the House of Commons. The steps leading up to the bridge are packed, people photograph themselves on their iPads in the shadow of Boadicea in her war chariot, the still impressive bronze monument designed by Thomas Thornycroft and placed here in 1902. Big Ben chimes midday; a city cruiser churns up the river water like dirty snow, there’s the slap of a police boat speeding under the bridge. Westminster Pier is similarly heaving; tourists buy ice creams and queue up for boat rides; pavement shops sell Union Jack umbrellas and postcards, while from somewhere up on the bridge comes the sound of a lone bagpiper.

Back in Birch’s day the scene was a more sombre one, ‘the wherries and boats which used to ply on [the Thames] have long gone. The steamboats, with their crowded decks, have gone also. Nothing is stirring on the tideway but a wretched tug, which hoots from time to time like some horrid monster in distress.’ The deserted river was no longer a popular highway, but a ‘receptacle for filth’ - as it had been for decades. A satirical etching by William Heath in 1828 showed just how concerned people already were about the state of the water, as a woman hurls down her teacup in horror when she sees monsters swimming in a magnified drop of Thames water. This was the year that a Commission on the London Water Supply reported on its investigation into the city’s drinking water, but it wasn’t until much later that a proper sewage system was installed. In the boiling hot summer of 1858 such was the stench that MPs in the Houses of Parliament were driven from parts of the building that overlooked the river. The curtains of the Commons were soaked in chloride of lime in an attempt to ward off the overpowering smell, and a Bill was rushed through to raise money for a new sewer scheme, designed by noted engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, and to build the Embankment. Both would have a significant impact on the river, the sewer making it cleaner and the Embankment making the Thames far narrower and its water therefore faster flowing.

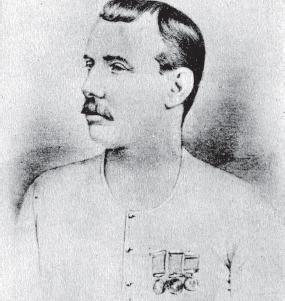

The work wasn’t completed until 1875, and in the meantime Captain Matthew Webb chose Westminster for a swim in order to show he was capable of swimming the Channel, an idea then dismissed as ludicrous. Webb, born in Shropshire in 1848, had grown up a seeker of adventure, daydreaming of one day performing ‘a great feat or act of heroism’. He learned to swim when he was eight in a ‘pond, or the River Severn, which ran near our house’. At the age of twelve he joined the merchant navy to fulfil a childhood longing for the sea and in 1873 received the Stanhope Gold Medal from the Royal Humane Society for trying to save a sailor who had fallen overboard. When in 1873 Webb read about J.B. Johnson’s failed attempt to swim the Channel he was inspired to try it himself. So he did what so many long-distance swimmers did after him: he swam in the Thames.

In 1874 Captain Matthew Webb swam six miles from Westminster Bridge in order to show he was capable of conquering the Channel, using a ‘slow, methodical, but perfect, breaststroke’.

On 22 September 1874 Webb went out on a boat from Westminster Bridge with swimming professor Frederick Beckwith and journalist Robert Watson. He ‘plunged immediately under the arch’ of the bridge and ended at the Regent’s Canal Dock, covering nearly six miles in one hour twenty minutes. ‘We grew tired of watching Webb’s slow, methodical, but perfect, breaststroke, and magnificent sweep of his ponderous legs,’ remembered Watson. Webb then made his ‘first public swim’ on 3 July 1875 from Blackwall Pier to Gravesend, twenty miles ‘of course with the tide’. It was this Thames swim that ‘greatly encouraged me in making the attempt to swim across the Channel’ and so off he went to Dover to start ‘practising’. On 24 August, on his second attempt, Webb swam from Dover to Calais in twenty-one hours forty-five minutes. He was the hero of the hour, the first person to swim the Channel without using any aids, and the toast of the nation.

Of all Thames champions, Captain Matthew Webb remains the most famous today, although it’s his Channel swim he’s remembered for. Webb completed other feats in the Thames, performed in the United States in tank shows, and in London at the Royal Westminster Aquarium, and took part in stunts, including a six-day swim at the Lambeth Baths. And all the time he was trying to come up with something - anything - that could surpass what he’d already done by crossing the Channel. In July 1883 he thought he’d found a new way to earn a fortune, but died while trying to swim through the whirlpool rapids on the Niagara River below Niagara Falls. His object, wrote Watson, ‘was not suicide but money and imperishable fame’. Today there is a memorial to Webb at Dover, and in his birthplace of Dawley where there is also a road and a school named after him.

Shortly before Webb’s Channel triumph, meanwhile, his rival Captain Boyton also set off from Westminster to swim the Thames. A couple of months earlier, in May 1875, he had already crossed the Channel and become an international celebrity - although unlike Webb he did it wearing a rubber life-saving suit. While Webb is included in the International Swimming Hall of Fame as an Honour Swimmer, Boyton is listed as an Honour Pioneer Contributor.

On 20 July 1875 Boyton left Westminster, clad in his famous suit, and walked down the House of Commons stairs, ‘loudly cheered’ by people on the bridge and where three special steamers with a ‘distinguished company’ accompanied him. Boyton paddled his way to Vauxhall Bridge within fourteen minutes and, as he reached Chelsea Suspension Bridge, received a ‘salute from the pier guns’. After three miles he had a rest, then got on to a boat and returned to the water at Hammersmith before arriving triumphant at Richmond.

Boyton was born in 1848, although it’s disputed if this was in Ireland or the United States, and was known as ‘the Fearless Frogman’. A ‘showman and adventurer’, he was a dedicated advocate of a suit invented by C.S. Merriman as a life-saving device for steamship passengers. The pair of rubber pants and shirt were held tight at the waist, while tubes could be used to inflate air pockets inside. Wearers remained dry and could float on their back, using a paddle to propel themselves feet first. This was one of many swimming aids and devices at the time, and in the coming decades inventors would patent a whole array of air bladders, buoys and floats, webbed gloves and winged boots, most of which were ‘crude and utterly illogical’, according to The Badminton Library.

Boyton swam up and down several rivers in the USA and Europe to publicise the suit and often, as was the case in the Thames, invited journalists to accompany him. He later toured with his own aquatic circus, opened an amusement park in Chicago and then one on Coney Island. Unlike all the failed Victorian swimming aids, the International Swimming Hall of Fame reports that a ‘similar suit’ is today used by the United States Navy and Coast Guard for sea rescue operations.

There were some other unusual swims from Westminster as well. In August 1878 a lieutenant in the Hungarian army decided to swim to Greenwich on a horse named Sultan. He was accompanied by a steamer carrying representatives of the Austrian, Spanish, Persian and Chinese embassies. However, the horse, perhaps unsurprisingly, didn’t like the cheering and after five miles the swim was abandoned because Sultan was ‘suffering from nervousness’. The lieutenant had recently patented a saddle with which to cross rivers on horseback and was clearly eager to demonstrate this, but he’d pledged to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty Towards Animals that he would stop if the horse were unhappy.

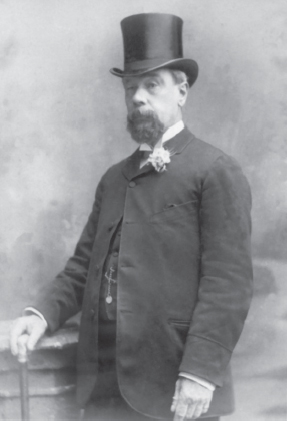

Ten years later Westminster was again the scene of a novel swim when Jules Paul Victor Gautier set off for Greenwich, the first this daring exhibitionist would make with his feet and hands bound with rope. Gautier was born in 1856 and by his early twenties was taking part in amateur swimming races. He was a pianoforte maker by trade, and in 1880 he first appeared in the press not for his swimming but because of his temper. One evening a man named Harry Scarborough was about to enter a pub in Camden Town when he thought he felt Gautier’s hand in his pocket and accused him of being a thief. Gautier, furious at the allegation, waited until Scarborough came out of the pub and ‘wanted to fight him’ until he was stopped by a police constable. Scarborough then boarded an omnibus; Gautier got on, too, but was pushed off by the conductor. So then Gautier, in single-minded fury, ran alongside the bus until Scarborough got off and went to a police station. Some twenty minutes later, as Scarborough was ‘proceeding in the direction of his home’, he was set upon by Gautier, who exclaimed, ‘I have got you now’, attacked him and kicked him, breaking his leg. Gautier was later arrested. He pleaded mistaken identity, but the jury found him guilty, although they recommended mercy ‘on account of the provocation which he had received in being falsely accused’. Gautier was sentenced to three months’ hard labour.

‘The daring professor’. Jules Paul Victor Gautier, who swam the Thames with his hands and feet tied.

A little over a year later he was back to swimming, taking part with four other men, all noted champions, in ‘the mile professional championship’ at the Welsh Harp in Hendon where he came last. He was described as ‘late of France’ and in the 1881 census he puts it as his birthplace. In reality, Gautier had been born in Islington, but for the time being he appeared happy to maintain the myth. By the end of that year an aquatic gala was held at the North London Baths ‘for the benefit of Jules Gautier, the champion of France’ and a few years later he was at the Lambeth Baths competing in the ‘Professional Swimming Association’s Handicaps races’, making two finals but each time coming fifth.

He took part in events at the Royal Aquarium, where he was described as ‘coming from Paris’, and worked as a swimming instructor or ‘professor’ to the North London Swimming Club. Then, on 16 September 1888, at the age of thirty-one, Gautier tried his hand at something a little different, swimming three and a half miles in the Thames with his wrists and feet tied. ‘Our old enemies the French are at us again,’ reported The Licensed Victuallers’ Mirror, ‘This time Waterloo went the other way. For the “fight was fit” within a stone’s throw of Waterloo on the South Western. It was a bloodless victory. Professor Jules Gautier represented France on the occasion … He is the Champion Long Distance Swimmer of that gallant and impulsive nation. He essayed the apparently impossible task of swimming from Westminster Bridge to Greenwich with his hands and feet tied on Sunday.’

The Victorians, and later the Edwardians, loved public feats of skill and endurance, the more bizarre, dramatic and potentially fatal the better, whether at fairs, music halls, seaside piers, agricultural halls or aquariums. Competing for a challenge and a wager were admirable things to do, while swimming as an organised event, with rules on everything from distances to clothing, was still in its infancy. When Jules Gautier set off from Westminster, extreme endurance events were all the rage, especially pedestrianism (competitive and often long-distance walking) which in some cases lasted six days straight. So it’s no surprise that a ‘dense concourse’ assembled on the Embankment to witness ‘the daring Professor’ who had ‘challenged all comers to try the feat with him. But all comers were no comers.’ Amid cheers from the crowds on land and in boats, and as Big Ben struck a quarter to one, Gautier jumped from a skiff and ‘took to the water like a duck’. Followed by ‘an interested mob’ on boats and protected by ‘a vigilant river police’ he reached Cherry Garden Pier ‘as fresh as he started. An enthusiastic demonstration awaited him here, and he expressed a wish to go on to Greenwich. As, however, he had beaten the record his friends did not consider this advisable. So he reluctantly left the water - the hero of the hour.’

Gautier, noted The Licensed Victuallers’ Mirror, was a ‘native of Normandy. He is 5ft 4½ inches in height. And he weighs ten stone. A wiry man who strips well. And though he has not a very powerful physique, looks capable of any amount of endurance. He has shown us Londoners how to perform a feat not long since deemed as impossible. A feat too which has its uses. For it demonstrates the perfect facility with which an accomplished swimmer can make his way through the water, no matter how heavily handicapped. Gautier swims with a side stroke, bringing his bound hands around in a semi-circle. It looks clumsy and awkward of course. But it is wonderful the pace the Professor can get on. He is a bold and skilful swimmer. And a modest and unassuming man. Good Luck To Him.’ Gautier completed the three-and-a-half-mile course in fifty-five minutes.

‘The long-distance swimming champion of France, Jules Gautier, has done rather a neat thing in natation,’ commented another paper. ‘We don’t admire big feet, as a rule, but Jules can certainly stand on his feat for bigness. Our good old national prejudice compels us to add, however, that, strange as it may appear, the “tied” was actually in his favour. Vive la France!’ The following year Gautier was appearing at a swimming exhibition at Clacton-on-Sea, where he was said to be ‘the champion of the world for speed’, born at Caen in Normandy but coming to England at the age of four. His trick swimming (popular in the period at indoor and outdoor venues and performed by both men and women) now included ‘smoking, singing, and writing; peeling, sucking, and eating an orange in the water, turning somersaults, the spinning wheel etc.’. He was still instructor to the London Swimming Club, and now to the Cholmeley School as well - the private boys’ school otherwise known as Highgate School.

The same year Gautier held an ‘annual costume entertainment’ at the Islington Baths and then in 1890 it was back to the Thames. ‘Shortly after four o’clock yesterday afternoon a man was seen to mount the parapet of London Bridge, near Fresh Wharf, and plunge into the stream. He was attired in a tight fitting bathing costume, and as he took the dive it was seen that his hands were bound together, as also were his legs just above the ankle. It afterwards transpired that the man’s name was Jules Gautier, the champion French swimmer.’ In 1891 he issued a challenge to swim against ‘any man in the world from Dover to Victoria Pier, Folkestone, with hands and feet tied, and allow them thirty yards start. This is not all. Gautier further undertakes to dive one hundred feet with hands and feet tied, and to take a clean header from the height of fifty feet with arms bound behind and feet tied. Jules, you see, is ready to face the foe. Is the foe forthcoming?’ The answer was presumably, no.

Gautier continued to take part in swimming entertainments and then in 1892 decided to try the Channel. But first he swam from Folkestone to Dover with his hands and feet chained, though some reports said he was taken out of the water about a mile from Dover. Soon after he dived 71 feet from a platform on Folkestone Pier with ‘his hands fastened behind him’ and his feet chained together. But the Channel attempt seems to have been abandoned because of the coldness of the water. In 1893 he was performing ‘sensational high dives’ at Captain Boyton’s World’s Water Show at Earls Court, billed as ‘champion Scientific High Diver and Trick Swimmer of the World’. The same year he tried to swim from Dungeness Lighthouse in Kent to Folkestone but was forced to give up.

In 1894 he began giving free swimming lessons to Islington ‘pauper children’. ‘The real value of a philanthropic measure of this kind is to be found in the fact that many of these children will probably enter callings which will expose them in a special degree to the risk of drowning,’ commented The Illustrated Police News admiringly. ‘Sailor and dock and waterside labourers of all kinds may be mentioned as a class to whom a knowledge of swimming would appear to be essential; and yet how few workers of this description take the trouble to learn the art?’ The paper noted that ‘not ten per cent of the merchant seamen’ knew how to swim, while in the navy ‘the men are compelled to learn, and very unwilling pupils many of them are too’.

Gautier continued to appear as a ‘speciality artist’ in vaudeville, dived from piers with his hands and feet manacled, and at the age of forty-two performed with one of his sons at New Lambeth Baths; he also wrote a book, Learning to Swim. Then, once again, it was back to the Thames, this time for a swim from Putney Bridge to Tower Bridge still with his hands and feet tied. Only now the issue of his nationality had been cleared up. A New Zealand paper reported that ‘Gautier was born in England, although both his parents belong to Normandy’.

In July 1904 Gautier dived from a boat just above Putney Bridge; ‘he adopted a peculiar stroke, his clasped hands being drawn swiftly downward, while his bound legs performed a fin-like twitch’, and when he got to Tower Bridge he ‘performed a series of evolutions and somersaults’ in the water. In 1907, at by now fifty, he swam nine miles from Richmond to Putney, announced he would again try the Channel, and the next year covered nearly sixteen miles from Blackfriars to Richmond. Then, in 1909, he added a new twist: still swimming manacled, only this time ‘he swam the university boat race course from Putney to Mortlake, towing a boat licensed to carry eight persons’. Gautier was tied to the boat with a rope, and won a wager of £100. In 1910 he again swam from Putney Bridge to Mortlake for a wager of £200. But then in 1919, at the age of sixty-two, Gautier’s incredible career came to an end when he died from pneumonia. Whether this was related to his swimming exploits isn’t known.

However, as in the case of Eileen Lee, his skills appear to have been passed on through the family, as I discover when I contact a Gautier family history website trying to find out more about the daredevil manacled swimmer. The response I receive is from none other than Jules Gautier’s great-grandson, Brian, a retired civil servant at the Ministry of Defence, who has done extensive research into his famous forebear. The bad news is that he’s leaving tomorrow for a two-month trip around Europe in his motor home. I worry we’ll lose touch and I’ll never get the chance to speak to a real life relative of a Victorian swimming hero, but then a few months later he gives me his number. ‘My great-grandfather Jules had a pianoforte factory in London,’ he explains. ‘Someone once did a family tree, which I found in family papers after my grandma died, and I used that as a starting point. I did know about Jules, because as a child I read the Lion comic and every week it had a page of feats. One week it was Jules Gautier who had swum nine miles in the Thames with his hands and feet manacled. I assumed he was related because he had the same name as my father, but my dad was faintly embarrassed by the whole thing. That was when I was small, but I always remembered it.’

Brian had also seen a photograph of Jules Gautier on the bow of a boat, with his three sons, Jules, Albert and Victor, but although the image belonged in the family papers somewhere along the line it disappeared. And why does he think Jules pretended to be French? ‘I think he just wanted to be someone he wasn’t, he went to prison and my theory is he came out and pretended to be someone else, although he didn’t change his name. I got the impression he felt offended being accused of being a thief and he tried to put it right but not in the right way. He wanted to put prison behind him in some way and it sounds more glamorous, to be French. His dad was born in France and came to England in 1850.’ How does he think Jules managed to swim when he was bound at the wrists and ankles? ‘I think it was a bit like doing butterfly, with a wriggle and a flick. I’ve had it described to me like that, pushing both hands down and scooping forward. And he waited for the tide so that would have helped. With the tow boat he was upping the ante.’

Brian’s father’s father, Albert, followed in Jules’ footsteps. In around 1922 Albert moved from Islington to the coastal Yorkshire town of Bridlington, where Brian was born. ‘He ran the baths in town, and taught local school children to swim. I never met him, he died a couple of years before I was born, but he was well known in town and people often say they were taught by him, including my wife’s mother.’ Albert was also an escapologist who did demonstrations off the pier, with his feet tied, and Brian started researching him as well. ‘The local paper had a load of stuff; he was a bit of a self-publicist, although he doesn’t seem to have mentioned his own dad, Jules. Albert had big crowds at his pier shows; it was the heyday of seaside holidays, and my dad had to go round with a hat to collect money, which is maybe why he was embarrassed.’ As for Brian: ‘I’m a fairly good swimmer but not competitive, but my grandson who is fifteen has just become Devon junior champion.’ Louis Jules Gautier is ‘well aware of the family tradition’; he recently won a scholarship to Kelly College in Devon, which has produced numerous international swimmers and Olympians. ‘He’s just been to a Geneva International Swim Meet with a team of thirty-three swimmers from Kelly who finished second overall out of fifty clubs attending,’ says his proud grandfather. ‘Watch this space.’

If it wasn’t for the way Brian painstakingly researched and put together a family tree, collating dozens of newspaper reports and photographs, it’s doubtful we would ever have known so much about Jules Gautier. Just as with Eileen Lee’s granddaughters and Hilda James’ grandson, he has kept the legacy alive. When I finish chatting to Brian and put down the phone I’m left wondering how many other people are out there with a champion swimmer in the family, just waiting for the right opportunity to celebrate them.

Long before Jules Gautier was making a name for himself in the Thames, meanwhile, plenty of others were swimming around Westminster as well, but their motive was simply enjoyment. The boys of Westminster School often swam in the river. ‘It was possible until the forties of the last century to enjoy a dip without going far from Westminster Bridge,’ wrote John Carleton in his 1965 history of the school. But tides and currents meant it wasn’t the safest pastime. The Annual Register for August 1781 notes, ‘Drowned, as he was bathing in the Thames, the 2nd son of Sir Charles Cox, Bart., an amiable and most promising youth of Westminster School.’

The usual place for pupils to bathe was off Millbank, a well-established bathing spot by the early 1800s. When in 1809 a Mr Crunden was arrested in Brighton for undressing himself on the beach before a swim, the defence noted that at Millbank where ‘the Westminster boys have from time immemorial been accustomed to bathe’ they did so ‘as fully as much exposed to public view as the East Cliff at Brighton’. But then canvas screens were put up around the school’s bathing place, just as they were at Eton and later at other Thames-side spots, thanks to headmaster Dr Edmund Goodenough. An entry from the Town Boy Ledger reads: ‘In order that the fellows might bathe without losing their clothes and being otherwise molested as formerly occurred a canvas of 30 yds. long and 6 or 7 high was this year 1825 placed at Milbank at Dr Goodenough’s expense.’ ‘Do bear in mind that the word “molested” had slightly different associations in the nineteenth century,’ comments Elizabeth Wells, the school’s Archivist and Records Manager; back then it would have meant to pester or annoy. Part of the river at Millbank was marked out for the boys, who were ‘attended by a waterman’, again just like the schoolboys at Eton. ‘Much to the credit of the more modern masters of Westminster School, bathing, which was only winked at formerly, is now allowed under precautionary arrangements, to ensure perfect safety,’ wrote R.B. Peake in 1841 in Memoirs of the Colman Family. The boys still bathed here until the late 1840s but then increasing pollution meant school bathing was transferred to the Lambeth Baths and later to a floating bath at Charing Cross. However, people continued to swim around Westminster. ‘The Thames is altogether such a wonderful affair,’ wrote Henry James in 1905. ‘From Westminster to the sea … in its recreative character it is absolutely unique. I know of no other classic stream that is so splashed about for the mere fun of it.’

In Victorian times swimmers chose Westminster as the place to carry out exhibitions of things never done before, whether Boyton in his suit, the lieutenant on his horse, or Gautier, the manacled man. Today even swimming within the city is seen as a major, and dangerous, accomplishment, and no school would take its pupils to swim in the Thames in central London. Health & Safety and fears of pollution would never allow it, yet when the Westminster boys swam Bazalgette’s new sewage system was still a pipedream.

At the beginning of the twentieth century the Thames still remained one of the greatest possible challenges for sporting swimmers, and was sometimes more ferocious than the Channel. On 18 July 1927 Mercedes Gleitze set off from Westminster to train for a Channel crossing, having already made several failed attempts. Her plan was to swim a staggering 120 miles from Westminster Bridge, down the Thames and around Beachy Head, to Folkestone, a feat unheard of for either woman or man. It was a journey that would take her twelve days and establish her as a pioneer when it came to Thames swimming. In 1890 Easton’s attempt to swim for six days from Oxford had ended in failure on the fourth day; now here was a woman easily completing a swim that lasted three times longer, with around forty miles of it in the Thames.

Mercedes Gleitze being greased up before a swim. In 1923 she set a record for a ten-hour, forty-five-minute swim in the Thames between Putney and Silvertown.

Born in Brighton in 1900, Gleitze learned to swim by the age of ten and on 5 August 1923 she had set a British women’s record for a ten-hour, forty-five-minute swim in the Thames, covering twenty-seven miles between Putney and Silvertown. This was her second attempt; she’d already tried the course a week earlier. Four years later ‘the London typist’, as the press repeatedly called her, set off from Westminster just before 6 a.m., accompanied by a motor launch whose skipper was a Mr Garman. But while she started with the tide the river became rough, she was swept off course and drawn under a group of barges, where she disappeared. ‘The suction was terrible,’ she later told reporters, ‘the Channel was not nearly so treacherous as this.’ She was trapped at a spot known as Church Hole off Wapping, said to be notorious for currents. ‘I was sucked down rapidly and all manner of thoughts rushed through my brain. I felt myself going down and down. I rapidly became resigned, and thought all was over. I wondered how long it would be before I was to enter another world. When I came to the surface in a few moments I quickly became myself again. Thereafter I was accompanied down the Thames by relays of Thames police.’

Press coverage of the swim was minimal in terms of details, such as where and when she began and ended each day, instead focusing on this ‘marvellous escape from death by drowning’. Gleitze had ‘come up by a miracle’ reappearing feet first and then floating motionless downstream before recovering, and local ‘longshoremen’ refused to believe it was possible. She continued her swim in a series of ten stages, swimming for six hours a day depending on tides, and taking only liquid food for the first two days before turning to solids. She arrived at Folkestone on the evening of 29 July, two days later than she’d planned, having been delayed by rough weather. Here she displayed her right arm ‘pitted with bright red spots’, presumably from jellyfish, between Canvey Island and Whitstable.

Then, less than three months later, on 7 October 1927, and on her eighth attempt, Gleitze finally crossed the Channel from France to England in fifteen hours fifteen minutes, making history as the first British woman to successfully complete the crossing. ‘Thank God, I am conscious,’ she declared, before collapsing on the shore in dense fog. Since Webb’s 1875 swim, nine other people had managed the Channel, including three British men and two American women. ‘Girl Conquers Channel,’ announced the national press, Mercedes Gleitze was now ‘the most amazing girl in England’.

However, some papers raised questions. The Dover Express noted that ‘there was no one ashore to witness the landing’ and that local motor boats ‘report that the visibility was not so bad as was stated’. ‘Miss Gleitze can have only one regret,’ said Sidney T. Hirst, Hon. Secretary of the Amateur Swimming Club, ‘and that is her oversight in not having on board any Press representatives and officials from the recognised swimming body.’ But the News of the World gave her £500 for her ‘plucky swim’, and she immediately signed a contract ‘to appear at a London theatre’ where she would be paid £100 for ‘a short speech’, her fees then going ‘to the London destitute’. Gleitze told one reporter, ‘when a woman sets her mind on doing a thing it just has to be done’. But, perhaps conscious of repeated comments as to whether a record-breaking woman could be still feminine, when asked if she smoked, she replied, ‘certainly not, I don’t agree with the principle of women smoking, just as I don’t believe in bobbed hair’. The paper then assured its readers that her own hair ‘looks very womanly’.

But unfortunately for Gleitze, four days later another swimmer, Dr Dorothy Cochrane Logan, a Harley Street physician and professional swimmer who swam under the name of Mona McLennan, set a new Channel record for women, with thirteen hours ten minutes. Only she didn’t: rather, she admitted, she’d done part of the course in a boat and had been paid £1,000 by the News of the World to claim a record swim. She said she was just showing why Channel records needed to be independently verified, but now Gleitze’s swim was in severe doubt as well, to which her response was, ‘All right, I’ll do it again.’ Like Lily Smith and Elsie Aykroyd who came before her and Ivy Hawke who came after, she exhibited the same sort of matter-of-fact determination. There had been previous bogus Channel claims. A Mrs Hamilton had ‘spent the night’ in a friend’s motor boat in Dover harbour rather than swimming; another had been towed across by her accompanying boat. Gleitze told the press she had never suspected Logan of lying: ‘what I have not got in my favour is the fact that no one saw me land’ (apart from those on the accompanying boat), and she agreed there needed to be a governing body for Channel swimming.

Mercedes Gleitze (centre) was the first British woman to swim across the Channel, but she found the Thames more ‘treacherous’. Norman Derham, the champion Southend swimmer, is behind her.

On 21 October, Gleitze set off on her ‘Vindication Swim’ in order to ‘restore the prestige of British women Channel swimmers in the eyes of the world’. As a result of the advance publicity, Rolex, which the year before had patented the first waterproof wristwatch, the Oyster, asked her to wear their prototype in exchange for a testimonial afterwards. This time she had the backing of a British businessman, Summers Brown, who had volunteered to finance the venture. And so, exactly two weeks after her first successful crossing, she entered the water once again at Cap Gris Nez. But after over ten hours, in water sometimes as cold as 50 degrees, she slipped in and out of consciousness, and seven miles from the end the medical officers accompanying her decided the swim should be abandoned. After protests from her to ‘let me go on’, those on the boat threw a twisted towel over her head and under her arms, and she was forcibly pulled on board.

The watch, which she actually wore round her neck, was still keeping good time and Rolex were quick to place a front-page advert in the Daily Mail with a picture of Gleitze, who became seen as a ‘poster girl’ for swimming. There was much coverage of her ‘splendid failure’, she had a ‘wildly enthusiastic’ welcome in London where she was besieged by autograph hunters and ‘an excited woman admirer broke through the throng at Charing Cross and kissed her’. Gleitze announced she was not going back to being a typist but would become a professional long-distance swimmer and ‘take up social-welfare work’.

By now she had signed a statutory declaration that her 7 October Channel swim was ‘a bona-fide one’, in the presence of the Commissioner for Oaths and a representative of the Daily Mirror. The declaration was also signed by her trainer, and on 1 November 1927 the swim was duly entered into the record book of the recently formed Channel Swimming Association, founded in order to authenticate swimmers’ claims to have swum the English Channel and to verify crossing times. Mercedes Gleitze’s record as the first British woman to swim the English Channel was now official.

And so began years of worldwide endurance swims. In December that year she set off to swim the Strait of Gibraltar. The following April, after five failed attempts, she finally succeeded in crossing the Strait, watched by ‘hundreds of women’, becoming the first person ever to swim the eight-mile course, in twelve hours fifty minutes. She also returned to the Thames and in December 1928, in water that was 36 degrees, swam from Tottenham Bridge to London Bridge on Boxing Day. The press reported ‘six other girls refused to enter the water because of the wintery conditions’. That same month she was photographed barefoot working in a Manchester cotton mill where she’d been employed for ten days under an assumed name ‘studying industrial conditions’. It’s unlikely no one would have recognised ‘England’s heroine of the day’ and the press, of course, were there to photograph her. But industrial conditions were close to her heart and she later used her earnings to set up the Mercedes Gleitze Home for Destitute Men and Women in Leicester in 1933, which survived until the Second World War.

‘The most amazing girl in England’: Mercedes Gleitze.

In 1929 she swam thirty-nine miles in the Thames in twelve hours, which must have been a record for a woman (no one had yet beaten Holbein’s fifty-mile continuous swim of 1908) and completed many endurance swims at indoor pools. During a forty-and-a-half-hour swim at Dundee Corporation Baths police had to ‘deal with an attempt to rush one of the doorways’ after ‘thousands were unable to get admission’. Gleitze travelled extensively in Europe, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, completing fifty-one marathon swims, nearly half of which took at least twenty-six hours. For many of these she was accompanied by music playing on a wind-up gramophone. Gleitze retired from swimming in 1933, after a failed attempt to cross the Channel from England to France, and withdrew completely from public life. She later became ill and eventually housebound, refusing to give interviews and shunning any further publicity, until her death in 1981.

Mercedes Gleitze is unusual when it comes to the story of Thames champions because, unlike other women, apart from Annette Kellerman, she is still honoured today. But until recently, just as with Webb, this was because of her Channel rather than her river swims. In 1969 she was inducted into the International Marathon Swimming Hall of Fame (IMSHOF), although it’s not clear if she was ever aware of this, and many press photos of her still exist, partly because she was so photogenic. Here she is standing on a beach, her legs being rubbed with grease, sitting on the floor doing warm-up exercises and, oddly, wearing dainty heeled shoes, or preparing to dive into the Lambeth Baths. Unlike Ivy Hawke ‘the smiling swimmer’, or Lily Smith, resplendently covered in medals, Gleitze often looks a little shy in these posed shots. But images of her during her Channel swim tell another story, of sheer exhaustion and triumph, and her story was suitably included in The Girls’ Book of Heroines.

Her legacy in terms of Thames swimming, however, has yet to be properly recognised. The fact that she swam 120 miles from Westminster to Folkestone in 1927 means she was the one who paved the way for the men who came after, such as Andy Nation, Lewis Pugh, Charlie Wittmack and David Walliams. When it comes to long-distance swims lasting days, it was a woman who got there first.

Lewis Pugh swims past the Houses of Parliament during his journey along the length of the Thames in 2006. Westminster has been the site of daring swimming feats since Victorian times.

Now at last Mercedes Gleitze is being celebrated as a pioneering open-water swimmer. In October 2013, at the Global Open Water Swimming Conference held in Ireland, she was enshrined into the IMSHOF as an Honour Pioneer Open Water Swimmer. This was followed in September 2014 by another enshrinement held in Scotland, this time into the International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF) as an Honour Open Water Pioneer Swimmer. In addition, a documentary, Mercedes: The Spirit of a New Age, has been made about Gleitze’s swimming career by Northern Ireland producer Clare Delargy, and a feature film is underway. Mercedes’ daughter, Doloranda Pember, meanwhile, has just finished writing a fully illustrated chronicle of her mother’s swimming career.

I meet Doloranda at Tate Britain, a fifteen-minute walk upstream from Westminster Bridge, where I’ve suggested we chat in the gallery’s restaurant because it first opened, although not to the general public, in 1927, the year of her mother’s record-breaking Thames swim. The Rex Whistler Restaurant was once considered ‘The Most Amusing Room in Europe’, thanks to its specially commissioned mural, The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats.

Doloranda is already seated when I arrive and I recognise her at once; she has the same delicate features as her mother. Behind her Whistler’s mural covers every wall of the basement room, in hues of green and blue with many a watery scene. Not long after it was completed the mural was under 2 feet of water as a result of the massive Thames flood of 1928, but it survived and has recently been cleaned. Doloranda has come by coach from her home in Gloucestershire and she’s brought some examples from her mother’s extensive archives. There’s a clink of cutlery and a chink of wine glasses from the lunch party at the table next to us, a waiter brings a tray of freshly baked rolls, then she begins to show me some of her mother’s treasures.

Mercedes Gleitze left over 2,000 documents, including letters, newspaper cuttings, photographs, witness statements and swimming logs in boxes in the attic, and Doloranda has spent several years charting every single swim. ‘Although she seldom spoke to us in detail about her achievements, because she left all these documents I’ve been able to record her career accurately in the biography I’ve just written. We had no idea how famous she’d been in her day. Now and again she might mention something but she kept her memories to herself, she was just a mother to three children and a housewife. She made herself invisible when she retired into domesticity and became totally reclusive. That’s why she isn’t as well known today as, say, Gertrude Ederle, but I’m about to put that right.’

Doloranda brings out one of the red exercise books her mother bought from Woolworths, its thick pages crammed with press reports. ‘She glued them all in, and when she ran out of glue because of war shortages, she sewed them in.’ Next she shows me posters announcing indoor swims, press photos from the Channel swim, a copy of the Channel Swimming Association’s verification of the crossing, and several pages listing all her mother’s endurance and open-water swims from 1923 to 1933. The collection is particularly important because when Gleitze returned home to her flat in Pimlico after her successful Channel swim in October 1927 it was to find that a leather travelling case presented to her by the Amateur Swimming Club had been stolen from her bedroom. The case contained ‘swimming articles, programmes, and a number of press photographs of the last few years’ and although there was money in the room, only the case was taken.

We talk about her mother’s Channel swim and Doloranda explains that a journalist who had been invited to accompany the crossing cancelled at the last moment. As a result of this, Gleitze would never again undertake a swim without it being properly documented, and as just one example Doloranda shows me the original documents attesting to the fact she swam the Strait of Gibraltar, page after page, in both Spanish and English, listing the names of every single spectator. But despite all these records, ‘the thinnest file I’ve got is on the Thames swims’, and, like me, she’s been frustrated trying to find out more details.

We finish our lunch and leave the Tate, walking along Millbank before crossing the road to the Thames. We sit on a bench in Victoria Tower Garden South, the wall that separates us from the river dappled in shadow from overhanging trees. The water today is as green as Whistler’s mural. The afternoon is sticky and muggy, we’re disturbed by planes overhead and motorbikes on the road behind us, and I have to listen carefully to hear Doloranda as she tells me the story of her mother and the Thames.

‘What do you think this was like,’ I ask, ‘when Mercedes swam here?’ ‘The Thames won’t have changed, or most of the bridges,’ she says, ‘but the London Eye,’ she lifts an arm to point across the river, ‘that’s new. And the water in the Thames in the 1920s would have been much more polluted, there would have been dead animals and other obnoxious deposits for a swimmer to contend with.’ But this didn’t deter Mercedes. ‘Most women still led restricted lives at that time,’ says Doloranda. However her mother ‘was one of the new women of that era, and was determined to follow her dream’, which in this case meant swimming the Channel.

‘American swimmers who came to try their luck were heavily sponsored by newspapers; they had the money and came here and trained full-time. British women didn’t have any funding. My mother had to earn a living; she was a working girl, she had rent to pay and limited holidays. She had little chance to train in the sea, and suddenly she had an idea one day, maybe she could use the Thames to train in at weekends. She lived in Pimlico and worked as a shorthand typist for a shipping company in Westminster, where her fluency in English and German was an asset. It was one of the new white-collar office jobs being offered to women, and better than domestic service. In the holidays she went to Folkestone to train, but at the weekends the Thames offered her similar conditions to the Channel because of its tidal flow. She walked along the Embankment every day to and from work and that’s what gave her the idea. It was not her original ambition to swim the Thames but she saw it as an opportunity. Swimming the English Channel was such a target, especially for a woman, because at that time no woman had ever done it.’

I say I’m amazed her mother could just get in and swim. ‘She couldn’t,’ explains Doloranda, ‘she got a licence from the Port of London Authority.’ I stare at her, astounded that the PLA granted Mercedes permission to swim in the filthy, crowded river in the middle of London. ‘She applied for a licence to swim on Sundays and they gave it to her. I find that incredible. The PLA didn’t raise any objections about health and safety; they didn’t say “no, it’s too polluted”. Mercedes just saw this body of water as somewhere to train. She used her initiative! Her motivation was to break records and make money for her planned charity, these were her parallel aims. On her walk to work she witnessed the unemployed, all the destitute people on the streets and under the bridges; this was during the years leading up to the Great Depression.’

I wonder if Mercedes worked in an office overlooking the river, and I ask where she swam from on these training weekends. Did she dive in from a beach or leap off a bridge? Did she hire a boat? ‘I don’t know,’ says Doloranda, ‘there are gaps in my knowledge.’ Another gap is the 120-mile swim, and I ask where her mother would have spent each night. ‘I suspect she would have got B&B accommodation at each of the landing places en route to Folkestone. It would have been the most practical thing to do. Unfortunately in her archives there are very few details of the actual swim - just about the start and the finish. However, I did find one press report that said she swam the tide out after that “near death” incident and landed at Erith at the end of the first stage. Lack of detailed information on this swim also frustrated me. I know the Daily Mail covered it because I have a letter she wrote to them asking for copies of the photographs they took of the swim.’

As for her liquid diet, Mr Garman, the boat skipper, would have handed her mugs of tea, coffee and hot milk, and when she turned to solids her menu while swimming normally consisted of egg and bacon, ‘which must have been difficult to eat in the water!’, ham sandwiches, fried fish, ‘a raw egg drink that was supposed to be nutritious’ - Doloranda pulls a face - ‘Bovril, Ovaltine, grapes, and on one or two occasions roast duck’. I ask if her mother was aware of the swimmers who had come before her, the women who also broke records in the Thames going back to Victorian times, and she says she doesn’t know and that the press reports in her mother’s archives don’t mention them.

For Doloranda, her years spent charting Mercedes’ swims have been enlightening. It has given her the chance to learn about her mother’s outstanding career - the details of which as a child she knew very little. Doloranda and her siblings all loved to swim, ‘but none of us had her ambition’. She has only swum once in the Thames herself, at Maidenhead sixty-five years ago with friends, when she remembers getting tangled up in reeds. And today she no longer swims in public pools, because ‘I’ve become sensitised to chlorine’.

Doloranda is immensely proud of the way Mercedes managed her own career and the fact that her ‘endurance swims in corporation pools gave city-dwelling people, especially women and girls, the opportunity to see a woman do physical things’. As for the charity her mother established, ‘although enemy action during the war destroyed the Charitable Homes, her Trust Fund is still active today and is being used to help people in poverty. The revenue from my book will go to Mum’s charity.’