Manage Your Pain: Practical and Positive Ways of Adapting to Chronic Pain - Michael K. Nicholas, Allan Molloy, Lee Beeston, Lois Tonkin (2012)

Chapter 18. Pain and Work

Summary:

Staying at work despite chronic pain is generally a good idea. There are many positives for us in working. Usually, working despite chronic pain requires some flexibility from both the worker and the workplace as some adjustments will be needed. But with goodwill on both sides, and good problem-solving strategies, most people with chronic pain can find useful employment. This chapter outlines some of the strategies that can be used to make work possible when you have chronic pain.

Pain doesn’t have to stop you working. In fact, many people with chronic pain continue to work and to find satisfaction in their work, even if they have to modify the ways in which they work. Understandably, however, many of the people who develop chronic pain do find it difficult to maintain their jobs as before. They may find aspects, such as the amount of sitting, standing or lifting, too difficult to keep up all day, even if they can do it for short periods. Some find that their employer is unwilling or unable to assist by agreeing to modify the demands of the job or to allow some flexibility. In these cases, the person with chronic pain may have to consider seeking more suitable employment. Some people with chronic pain appear to struggle on as they don’t want to lose their job or they fear they will be unable to find anything better elsewhere and they need the money. In these cases, we often find that people in this position do little else than work then “crash” when they get home at the end of the day. Their home and social lives may bear the brunt of the drive to stay at work.

It is also true that many people with chronic pain find they cannot continue to work and give up hope of ever getting back to work. Finding a job that you can do without aggravating your pain so much that you can’t do anything when you get home is often difficult. In general, the type of work (especially how physically-demanding it is) can influence your chances of returning to work or keeping your existing job. Interestingly, however, evidence from the New South Wales WorkCover Authority suggests that it is not just the nature of the job that is important. For example, the proportion of injured workers who haven’t returned to work within 6-months of injury is very similar for manual and office workers (17% versus 16%).

Whether or not someone returns to work after an injury depends on many issues apart from the nature of the job. For example, the availability of a suitable job, the skills of the worker (clearly, the more skills you have the better your chances will be), and the willingness of an employer to take on someone with a history of injury (especially if they have had a workers compensation claim in the past). Some, of course, do not want to return to work and may settle for improving their quality of life at home.

Despite the obstacles, many people with chronic pain do return to work. We have tried to learn from their experiences.

Peter was a classic example. Peter’s job was at risk. Attending our program and showing that he could be reliable at work was Peter’s last chance, and Peter was very keen to keep his job. Therefore he was committed to attending for our 3 week program. However, his attitude and behaviour in the first week made it clearly evident that he didn’t really believe any of this could make any difference.

However, to his credit, he persevered and attempted to at least trial the strategies. Early in the 3rd week, when Peter was making significant gains in coping with his pain, and was seeing improvements in his personal life at home, Peter said to us “You know, I really didn’t believe any of this could help in the first week”. We looked in mock surprise and said, “Oh, is that so, Peter?” “Was it that obvious?” he asked.

But Peter did apply the strategies, and was extremely proud of himself, and pleased with the significant progress he had made. A meeting was arranged with the relevant people from Peter’s workplace and he returned to work confidently following the program, believing that he had the skills required to satisfy the demands of the workplace, as well as his personal life.

This chapter outlines some of things we have learned from experiences like Peter’s. As with the other complex issues covered in this book we would recommend that you seek out professional assistance if you are not confident about dealing with this area on your own. In every country there are public and/or private agencies that can help people return to work after injury. Initially, most injured workers will be effectively guided by their doctor. But other health professionals, as well as employers, can also help. Access to different services varies between countries and you may need to get information on what help is available in your country. Usually, this information can be obtained from your doctor, employer, union or Government agencies. In the UK, for example, the offices of the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) should be able to give you advice on available rehabilitation services. A recent innovation in the UK has been the creation of the position of Personal Adviser in the DWP as a means of providing disabled people with advice and help in finding suitable assistance for overcoming the many obstacles faced when attempting to remain at work or to find new jobs.

It is important to realise that while your doctor is able to advise you on the best treatments for your injuries and pain, he/she may have limited knowledge and expertise when it comes to return to work issues. You are likely to need additional help, especially if you are having (or have had) trouble returning to work. This is especially true if you have been out of work for many weeks or months. We recommend that you discuss with your doctor the sorts of difficulties or obstacles you are facing in returning to work, but also say that you didn’t expect him/her to solve these problems for you. Instead, you could ask his/her help in finding out who could provide assistance in this area. It would be ideal if you and your doctor could work in a cooperative way with whoever is able to help you in your efforts to return to work.

In many cases, returning to one’s previous type of work may not be realistic. You may need to consider looking for ways of retraining or learning new skills to help you become employable again. Most countries offer training in practical work skills through technical colleges, but available courses are likely to differ from place to place. You will need to do some asking around to find out what is available near you.

Things to consider about work and pain

(1) Do you want to work? This may seem an odd question, but there is little point in going through the motions of trying to work if you really don’t want to. How could you know? At present you may not feel like working, but who knows, this feeling may change as you apply this programme and get more confident about what you can do. Re-examining the chapter on setting goals could help you to work out your priorities here.

(2) Is it realistic for anyone in pain to work? In general, the answer is yes. As mentioned earlier many people work despite pain. Providing they can make the necessary adjustments (such as pacing activities, modifying postures and minimising difficult tasks), many people have returned to work after injury despite persisting pain. Naturally, this is usually best done by negotiating with your employer about what you can manage and what assistance or accommodations you require, at least to begin with. Over time, as you build up your tolerances these arrangements can change.

One patient who attended our programme at the hospital, for example, was taking over 400mg of morphine a day and was unable to perform her clerical job. Nevertheless, her employer said he was willing to take her back if she could attend reliably and build up her hours over time. After attending the programme with us she was able to cease her use of morphine and had paced up her exercises to the point where she felt ready to return to work for a couple of hours a day. The employer agreed and a return to work plan was arranged. The plan involved her gradually pacing up her time at work, starting with two 2-hour blocks a day for three days a week (working every second day). Her 2-hour work blocks were separated by an hour or so when she would do her exercises at a nearby gym. At the time of writing (about 16 months since she completed the programme), this patient is still working (now 5 hours a day, 5 days a week), and she has not taken anything for her pain for over a year. She is happy with this work level as it still leaves time for other things she likes to do and she doesn’t burn herself out at work. We believe that one of the key reasons for this lady’s success was the willingness of her employer to compromise and find ways of helping (as opposed to blocking).

A large study in the state of Michigan in the United States of America also found that those employers who found ways to help their injured workers return to work tended to have better success in return to work rates than those who did not. So, when an employer says they have “no light duties” or “you have to be 100% fit before you can come back to work”, it seems to us that such employers are not really trying to help someone return to work. Remember, most people who work are not that fit.

(3) Using problem-solving. Working despite pain is clearly an area which requires good problem-solving skills. Often the best solutions will not be ideal, but they may be better than not working at all. Re-read the chapter on problem solving (Chapter 15). One good example of this was a man who had been a truck driver when he was injured. A year or two later when his pain had not improved he attended our programme and, despite being quite despondent before it, he did pick himself up and when he returned home he managed to get a new job as a tour bus driver. He has kept this job for a couple of years now and he looks a different person to the one who attended our programme. When we asked him how he managed to keep driving with his painful back, he said he had worked out that if he stopped the bus every hour or so (to give the tourists an opportunity to get off the bus and take a look about) he could keep his pain under control. So he had found a job that he had the skills to do (as a former truck driver) and he could still pace his sitting so that he didn’t overdo it and stir up his pain.

(4) Dealing with stress. A number of studies have shown that workers who are dissatisified with their jobs and feel stressed or unhappy at work, tend to have more trouble in returning to work after injury. On the other hand, some recent treatment studies in Scandinavia have shown that if injured workers with back problems learn effective ways of dealing with stress they have more success in staying at work. Have another look at the chapters on Challenging Ways of Thinking About Pain (Chapter 11), and Stress and Problem-Solving (Chapter 15). If you find your work is made harder by stress, then you may be able to improve how you are dealing with it. This may also help you stay at work.

However, it is also true that other people at work will often be part of the problem. It could be your boss or other workers or colleagues. Have another look at the chapter on Interacting With Those Around You (Chapter 16). This could help to prepare you to deal with others at work more effectively. This is also an area where a rehabilitation provider should be able to assist you and help you to negotiate a reasonable arrangement with your boss, as well as other colleagues. If these problems are related to your not being able to do as much as you used to do, due to your pain, it might help to show them this book.

Remember what you were like before your pain became chronic? How would you have looked at someone like you now? Maybe you could discuss this with your colleagues or workmates? Some people with chronic pain have told us that they looked for ways of “trading” some of their duties with others, so that they did some of the tasks the others normally did, while the others picked up some of their more difficult tasks. Naturally, this can be awkwardand this could be an area where the help of a trained rehabilitation provider could make a big difference.

(5) Alternatives to work. Whatever has caused your pain, it is helpful to return to your normal activities as soon as possible, to avoid becoming depressed and despondent, as well as disabled. This includes returning to some sport or fitness activity, even a simple walking program, preferably with some company. Your local community services, council or library can often be a good source of information on what is available in your district.

Another way of gradually resuming some fulfilling activities is to do some voluntary work. Most local councils will be able to give you information about what is available. If you are not ready (or don’t wish) to return to paid work just yet, then doing some voluntary work can be a first step. This can not only help you to feel useful, but also it can give you some useful “on the job” training and help you to get up to “freeway speed” and ready to return to more demanding work.

Ergonomics

For a lot of people, a large part of their day is spent in one position. This may be at a desk in front of a computer or studying, driving long distances, standing at a work bench or any number of positions. Or maybe you are only doing activities for relatively short periods, such as ironing. Whatever you are doing, it is important that you look at your work environment and make sure that it is as comfortable as possible for you. If you would like more advice on the best layout for your office or work-space you could consider consulting an ergonomist. Ergonomists are people who have special training in this area and they can be a good source of ideas for what might help you.

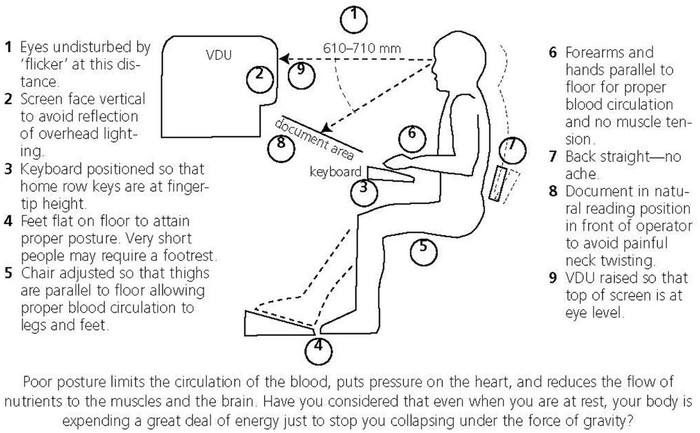

An example of sitting at a computer is given here. Sometimes it means making some changes to the area in which you are going to work, but in the long run it is worth it.

However adjusting equipment alone will not be all that is required. It is important to assess your work flow and the activities you are performing and to plan them so that you can make regular changes in your position using pacing to gradually do more. An awareness of your posture and the ability to change your posture remains essential to optimise work safety.

Sofia was a good example of these principles.

Sofia was suffering neck pain following a motor vehicle accident. She was a school teacher and was keen to resume marking exam papers. However, the fixed posture involved with reading and writing was a problem. She was able to use a sloping desk board and had adjusted her sitting posture. She had also been working on building up her tolerance for using her arms in a fixed position. As a result, she had learnt that there was a time limit that she could sit and mark papers. Therefore she set her timer and took a short break and changed her position. Eventually she found that she could actually mark more papers, and not suffer so greatly at the end.

In conclusion

Clearly, there are many issues involved in returning to work while still in pain or staying at work despite pain. In some cases it is likely that the demands of the job will be too much to manage. In these cases, consideration about alternative options is clearly wise. In other cases, it may just be a matter of re-examining the nature of the work and trying to work out more effective ways of managing. Whichever is the case for you, we would strongly recommend that you use this book to make sure you have as many of the skills as possible to handle your job despite pain. It can also be helpful to involve others, like your local doctor, and your family. But, consistent with the theme of this book, we would recommend that you try not to let pain stop you achieving your return to work goals.