Improve Your Memory Every Day (2015)

Memory Techniques

The first part of our course is devoted to finding out just how good your memory is now, and then teaching you how to improve it. You can learn a lot in a very short time, By the end of just one day of study, you will have at your disposal a variety of powerful memory tools that will last you a lifetime, But don’t stop there! The more you use your new-found powers, the stronger they will become, Eventually, with regular practice, you will have a foolproof memory that will serve you well in all areas of your life.

You can learn a lot in a very short time.

Become more efficient and professional.

You will have at your disposal a variety of powerful memory tools.

How do you learn?

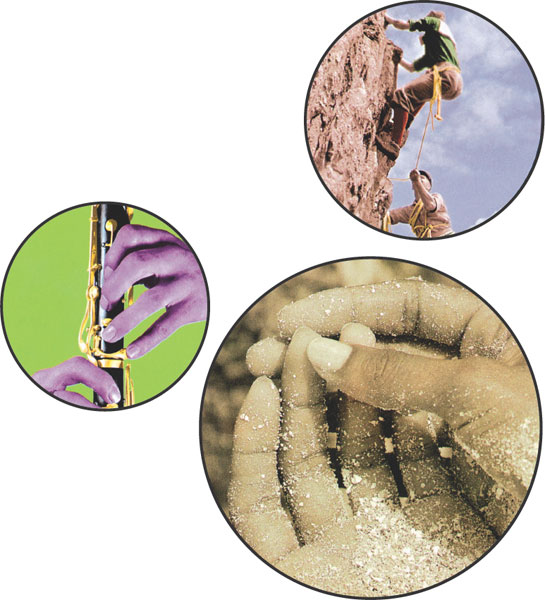

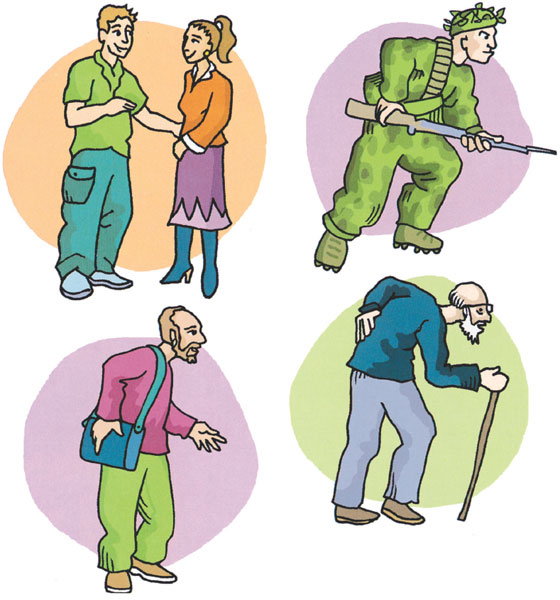

There are three ways in which we learn: looking, listening and doing. Of these, most of us have a favourite that we tend to rely on, a second method we use as a back-up, and a third method that we feel less comfortable with. Some lucky people can use all three styles effectively and some unlucky people are completely deprived of one or more of them (for example, blind students can gain nothing from visual learning). The following test will tell you how you rate on each learning style. See ‘What does it all mean?’ (opposite), for a description of your personal learning style.

1 At a lecture, you may learn in several ways. Which is your favourite?

a) Listening to the lecturer.

b) Copying down notes from a whiteboard.

c) Carrying out practical tasks based on what you learned in the lecture.

2 When you go to a movie, what do you remember best afterwards?

a) The dialogue.

b) The action sequences.

c) The things you did: driving to the cinema, buying tickets and getting popcorn.

3 How would you learn to fix a flat bicycle tyre?

a) Get a friend to describe how to do it.

b) Buy a repair kit and read the instructions.

c) Get to work with a spanner and figure it out for yourself.

4 If you wanted to learn the names of all the presidents of the USA, would you:

a) Make up associations for each name (such as think of Lincoln as a car)?

b) Look at portraits to help you remember their names?

c) Get a set of pictures, cut them out, label them and put them in an album?

5 If you like a pop song, which of these activities would you enjoy most?

a) Learning all the lyrics.

b) Watching the video constantly.

c) Trying to imitate the dance routine.

6 How well do you see things in your mind’s eye?

a) Poorly.

b) Very well.

c) Reasonably well.

7 When it comes to practical tasks using your hands, are you:

a) Average?

b) Excellent?

c) Poor?

8 If someone reads you a story, do you:

a) Remember it in great detail (parts of it word for word)?

b) See a sort of home movie in your mind?

c) Forget it quickly?

9 As a small child, which of these did you prefer?

a) Reading.

b) Drawing and painting.

c) Playing with a shape sorter.

10 If you moved to another town, how would you find your way around?

a) Ask the locals for directions.

b) Buy a map.

c) Walk the streets until you became familiar with their layout.

11 Do you tend to remember best:

a) The actual words people say to you?

b) The way things look?

c) Things that you do?

12 Which do you remember most vividly?

a) Poems you learnt at school.

b) What your childhood home looked like.

c) How it felt to learn to swim.

13 When gardening, do you:

a) Know the names of all the flowers and plants?

b) Recognize plants but forget their names.

c) Concentrate on practical tasks such as weeding and pruning?

14 Do you:

a) Read a newspaper every day.

b) Always make sure you see the news on IV

c) Don’t keep up with the news because you’d rather spend the time on something practical.

15 Which would cause you most distress?

a) Having impaired hearing.

b) Having impaired vision.

c) Having impaired movement

What does it all mean?

Listeners

If your answers are mostly ‘a’, you are a listener. You enjoy sounds, especially words, and you find they have powerful meanings for you. You are far more likely to remember and understand anything that you take in through your ears than information received through some other channel.

Lookers

If your answers are mostly ‘b’, you are a looker. You respond best to visual stimuli, which hold the most meaning for you. Anything you see will be easier to comprehend and retain than information from other sources.

Doers

If your answers are mostly ‘c’, you are a doer. You like to get your hands dirty (often quite literally). You learn best from practical experience - five minutes with your sleeves rolled up doing a practical job is, for you, a much more profound experience than several hours spent in a lecture theatre. If you’re lucky, you may have found that you answer equally well in more than one category. It is rare for anyone to learn exclusively in one style. Certainly, it is to your advantage to use all three learning styles wherever you can, because a combined attack is far more effective. If you find that you hardly use one style at all (looking, for example), you might have an undiagnosed problem in this area. An eye examination and a pair of glasses just might open up a whole new world to you.

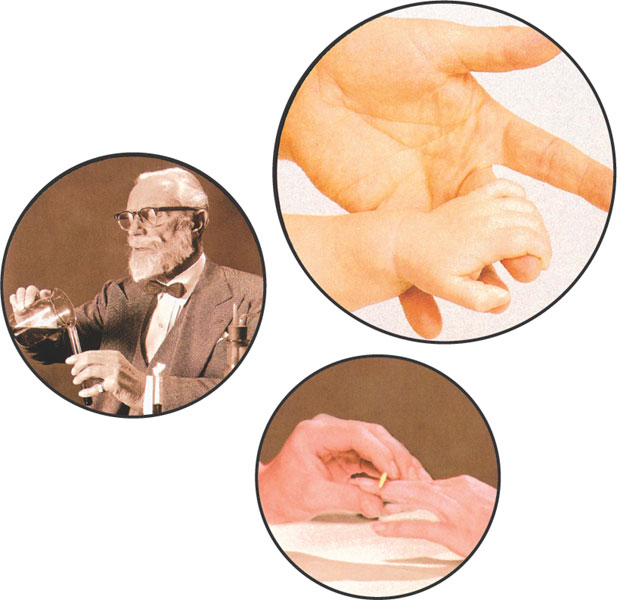

Build your own powerhouse

Concentration is the powerhouse of memory. No matter how many tips and tricks you learn from this book, your memory will not reach its full potential unless you learn how to concentrate. This is not something that comes easily to most of us nor, in spite of its huge importance, is it something that we are taught at home or at school. When I was at school, the teachers would yell, ‘Concentrate, boy!’ but they might just as well have said, ‘Levitate!’ for all the good it did. I didn’t know how to concentrate - not at will, anyway. Like most people, I could concentrate furiously on what interested me - a good book would do the trick but had trouble bending my mind to Latin case endings or quadratic equations.

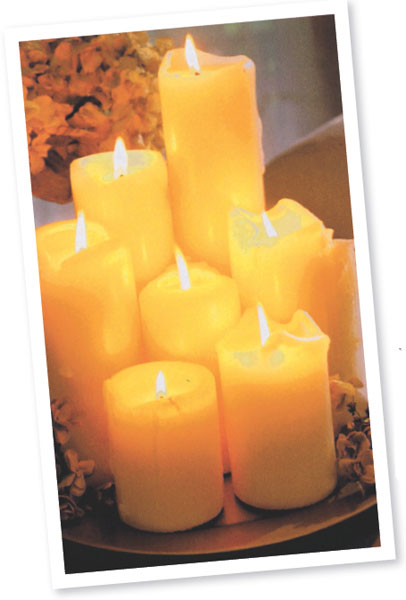

When I was older and became interested in mind-training techniques, I discovered that concentration was considered a necessary skill in many Far Eastern cultures, and that there were techniques for teaching it. Here is one of them, which you might find useful. It is several millennia old, but none the worse for that:

![]() Light a candle and set it on a table in front of you.

Light a candle and set it on a table in front of you.

![]() Stare at the candle for a couple of minutes. Try to remember every detail - the colour and texture of the wax, the appearance of the flame and the way it moves. Fix it all in your mind.

Stare at the candle for a couple of minutes. Try to remember every detail - the colour and texture of the wax, the appearance of the flame and the way it moves. Fix it all in your mind.

![]() Now close your eyes and try to retain the image of the candle in your mind’s eye for as long as you can.

Now close your eyes and try to retain the image of the candle in your mind’s eye for as long as you can.

![]() Your first efforts will probably be pitiful. This exercise looks easy but isn’t.

Your first efforts will probably be pitiful. This exercise looks easy but isn’t.

![]() Keep trying again and again. Eventually, you will be able to hold the image of the candle in your mind’s eye for as long as you wish.

Keep trying again and again. Eventually, you will be able to hold the image of the candle in your mind’s eye for as long as you wish.

Concentration training

What other things must you do when you concentrate? One is to, structure your time. Set aside a specific time for doing a particular task and try not to deviate from that. It is quite natural to sit down to a task, especially one that you don’t really enjoy, and then think of something important you need to attend to. Then you fancy a coffee. Then you go to see if the post has arrived. Then the phone rings and you spend time chatting. Then, since you’re already on the phone, you call a friend and waste some more time chatting. If you recognize this scenario, you not only need to practise concentration regularly, but also to structure your time. Make yourself a timetable and slot in all the tasks you hope to accomplish.

When you construct the timetable, bear in mind the way your day normally unfolds. Don’t allot complicated tasks to times when you are usually disturbed. Remember that there are quiet times that often don’t get used (early mornings, for example), which are really valuable if you need to work undisturbed.

If, as your work progresses, you find that your initial time estimates were faulty, you can correct them. That doesn’t matter. But what does matter is that you stick to your task until it is accomplished and do NOT let yourself be distracted.

Incidentally, if you think I’m one of life’s naturally ordered workers, who concentrates effortlessly, you’d be quite wrong. Everything I’ve written above is the product of bitter experience and oceans of wasted time. But now this section of the book is finished and I’m going for a coffee (after amending my timetable to show that it took me twenty minutes less than I’d planned).

Take a couple of minutes to consider whatever task is before you. Don’t just rush into it, but consciously decide what methods you could use to complete it, and how long it should take. Once you have decided on the length of the session, stick to that decision and let nothing stop you.

The truth is, a person‘s memory has no more sense than his conscience, and no appreciation whatever of values and proportions.

Mark Twain, Eruption

Body and mind

For your memory to work properly; you need to look after yourself. It’s no good assuming that you can put your mind to work whenever you want and despite the way you have treated yourself. Remember that your body and your mind are one. In fact, your mind is all you will ever know. Anything that is outside your mind simply does not exist for you and never can exist, because the moment you are aware of it, it is part of your mind. Thus, even your body is only available to you as a mind object. So, looking after your mind and body is really; really important. Here are some things you need to bear in mind if you want to function properly. (None of what follows is very complicated. You’ve heard it all before. So, why aren’t you doing it?)

Get enough sleep

This applies to everyone, but is particularly important to youngsters studying for exams. They are the ones who think that staying up until 3 a.m. every night chatting to their mates on the Internet is a really cool idea. It isn’t. Sleep deprivation ruins concentration and reduces your ability to learn. It is also generally detrimental to your health.

Eat sensibly

A good diet is essential to mental and physical health. Junk food is called that for a reason. Try to eat lots of fresh fruit and vegetables. There is no specific brain food, but eating lots of pizzas, burgers and takeaways will do dreadful things not just to your memory but to your general health. One thing is very important: eat breakfast! Researchers have found that those who eat breakfast have better powers of recall than those who don’t.

Get fresh air

Like concentration, breathing is something that we aren’t taught. Of course we do it naturally; but there are ways to do it more efficiently. Make sure, when you work, that you have a window open. Keep the room at a comfortable but not excessive temperature. Learn to breathe properly (see ‘Take a deep breath’, opposite).

Get exercise

You don’t have to live at the gym, but you do need a certain amount of exercise for your mind and body to function at maximum efficiency. Walking the dog (briskly) or mowing the lawn will do just as well, if you hate sports. But why not put in a little bit of extra effort and go for a long walk; or a swim? The dividends in both the long and the short-term are well worth the input.

... little threads that hold life’s patches of meaning together.

Mark Twain, Morals and Memory speech

TAKE A DEEP BREATH

Learn to breathe properly:

![]() Sit quietly on a straight-backed chair.

Sit quietly on a straight-backed chair.

![]() Sit upright but don’t strain (your muscles should be relaxed).

Sit upright but don’t strain (your muscles should be relaxed).

![]() Imagine that there is a strong thread that connects the top of your head to the ceiling.

Imagine that there is a strong thread that connects the top of your head to the ceiling.

![]() Tuck your chin in very slightly.

Tuck your chin in very slightly.

![]() Close your eyes and breathe normally for a few minutes until your body and mind start to calm down naturally. Now comes the part that requires practice.

Close your eyes and breathe normally for a few minutes until your body and mind start to calm down naturally. Now comes the part that requires practice.

![]() Very gently, draw the air down as far as you can. At first, you will only be able to get it down as far as your diaphragm. Surely that’s enough? You can’t go any lower, can you? Yes, actually you can. According to many Far Eastern schools of thought, there is an energy centre (called hara in Japanese and Tan Tian in Chinese) situated about 4 cm (½ inch) below the navel.

Very gently, draw the air down as far as you can. At first, you will only be able to get it down as far as your diaphragm. Surely that’s enough? You can’t go any lower, can you? Yes, actually you can. According to many Far Eastern schools of thought, there is an energy centre (called hara in Japanese and Tan Tian in Chinese) situated about 4 cm (½ inch) below the navel.

![]() Try to draw the breath into this point - it is possible. All it takes is practice and, once you have learnt to breathe this way, you’ll find that it has huge benefits for both mental and physical well-being.

Try to draw the breath into this point - it is possible. All it takes is practice and, once you have learnt to breathe this way, you’ll find that it has huge benefits for both mental and physical well-being.

Stuff to avoid

If you have never woken up in the morning unable to remember the events of the previous evening because you were a tad too enthusiastic with your drinking, I congratulate you. Most of us have done it at one time or another and you don’t need me to tell you that it’s a bad idea. If you want your memory to work well, booze is a very bad idea indeed, as are all drugs (including nicotine). An occasional indiscretion will produce a mere memory blip, but long-term abuse can mess up your mind in various unpleasant ways. Loss of memory will almost certainly be one of them.

The state of the art

How good is your memory right now? The following pages will seek to assess the current state of your memory with a series of tests that increase in difficulty. Just use whatever memory methods you normally use; it really doesn’t matter if you do badly. The idea of this section is to show you just how much you can improve your memory by putting into practice the techniques taught later in the book.

SHORT-TERM MEMORY TASK 1

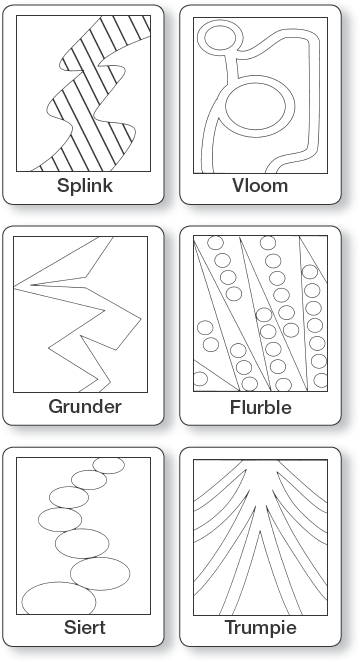

The ‘Flurble’ test

TIME: 3 minutes LEVEL:Easy

Instructions

1 Study the six pictures with strange names.

2 Spend three minutes memorizing them.

3 Now close the book, draw all six objects and write the correct names beneath them.

4 Check your answers against the original pictures.

5 Now spend a further five minutes - memorizing the original pictures.

6 Leave this exercise and then tomorrow, without further memorizing, try to draw and name what you can recall.

How did you do?

Although memory is always capable of improvement, if you were able to draw and name all six pictures on both occasions, your short-term memory is working well.

Retest: To test yourself further, go back to this task in, say, six weeks’ time and see if the memory has become a long-term one.

Remember this!

Memory works best by association. Try to think of things that remind you of the shapes and names you are trying to memorize.

SHORT-TERM MEMORY TASK 2

It happened last Friday

TIME: 3 minutes LEVEL: Easy

Here’s another easy test of your short-term memory: All you have to do is read through the passage below. You can study it as hard as you like for three minutes, then cover the story and answer the questions:

Last Friday, Jim’s wife, Sandra, asked him to go to the shops and buy some things ready for her parents’ visit at the weekend. She needed a couple of pizza bases, some canned tomatoes, mozzarella and a couple of bottles of wine. She told him to go to Brown’s because it was cheaper than Thompson’s (and anyway Tommy Brown was her cousin). She told him to stop on the way back and get the car cleaned, and to pick up their twins, Mark and Michael, from school. Jim was almost home when he discovered that he’d forgotten the cheese, so he went back to town. This time he went to Thompson’s, because it wasn’t as far to drive. He also bought a bag of pretzels and some salted peanuts because he remembered that his father-in-law, Dick, liked them.

Questions

1 What is Jim’s father-in-law called?

2 Which shop does his wife tell him to go to?

3 What does he forget on his first attempt?

4 Why does he go to Thompson’s rather than Brown’s on his second trip?

5 What are the names of Jim’s twins?

6 Where is he supposed to pick them up?

7 What is Jim’s wife called?

8 How many bottles of wine is Jim supposed to buy?

9 What canned goods does Jim’s wife ask him to get?

10 What is he supposed to do with the car?

11 When are his wife’s parents due to visit?

12 What is the connection between his wife and the owner of Brown’s?

13 What sort of cheese does Jim forget to buy?

14 What does he buy specifically for his father-in-law?

15 On which day does the story take place?

SHORT-TERM MEMORY TASK 3

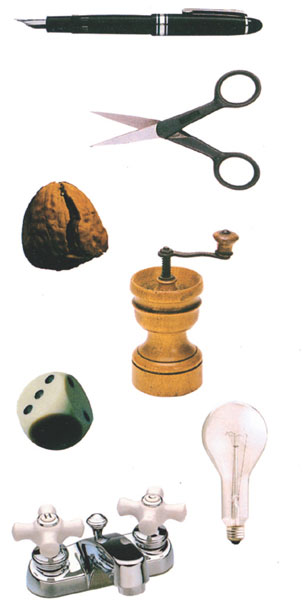

Kim’s game

TIME: 3 minutes LEVEL: Medium

Here’s a more difficult task to test your visual memory. In Rudyard Kipling’s book Kim, the young hero was trained in observation by being told to look at a tray full of objects and then, when the tray was removed, he had to remember as many of them as possible. Kim’s game has long been a favourite at parties but it also has a serious role in memory training. There are 25 objects pictured on these pages. Your job is to look at them for three minutes and try to fix as many as possible in your mind. Then, with the book closed, write a list of what you can remember. If you don’t get all the objects first time - and you’d have to have a very good memory to do that - you can have another go (and another) until you get the whole lot.

DON’T PANIC!

You won’t be able to bring things to mind if you are in a panic. Give yourself time and work calmly. (If you’re revising for a test or exam, start in plenty of time and don’t try to do it all the night before.)

A diplomat is a man who always remembers a woman’s birthday but never remembers her age.

Robert Frost

Can anybody remember when the times were not hard and money not scarce?

Ralph Waldo Emerson

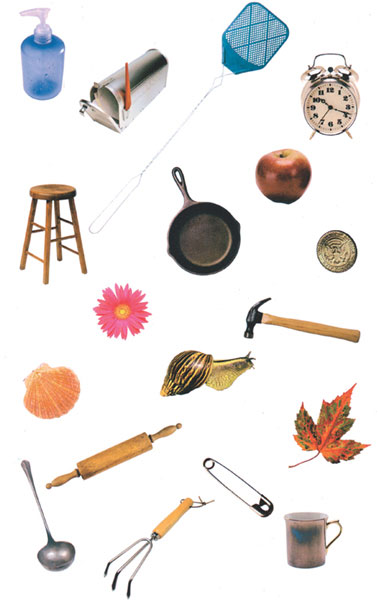

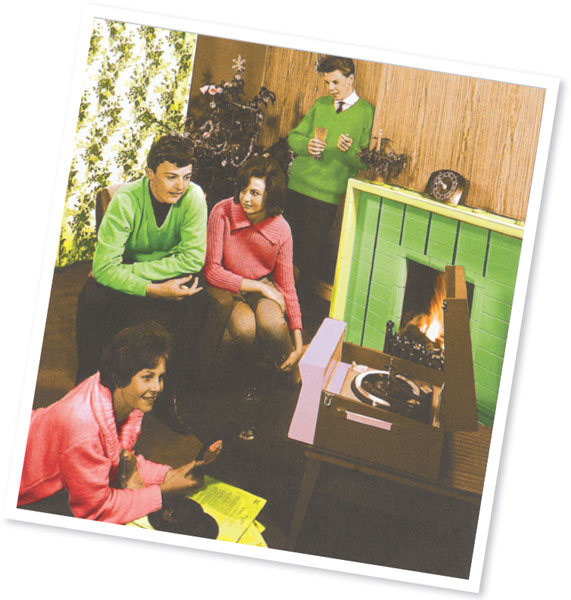

SHORT-TERM MEMORY TASK 4

Deceived by appearances

TIME: 3 minutes LEVEL: Medium

This is one of those spot-the-difference games that will really test your visual memory. The picture on this page is the original and the one on the opposite page is the altered version. On this occasion, however, the game is played slightly differently from usual. You need to look at the left-hand image for three minutes and try to fix it in your mind, then cover it up and try to find fifteen differences in the right-hand picture.

The differences are all quite obvious. This is not a puzzle to test keen observation. All you need to do is fix the first picture firmly in your mind and then spot the major changes that have been made.

STUDYING AND RECALL

If, in spite of all the advice in this book, you find some facts just won’t stick in your mind, take time to work out why. If they are too boring, use wild and wacky associations to make them more memorable. Really childish humour works wonders. But if you still get no result, consider why you cannot remember. Is your subconscious telling you that you’re studying the wrong course?

Does the material that you’re trying to remember have bad associations that you aren’t acknowledging?

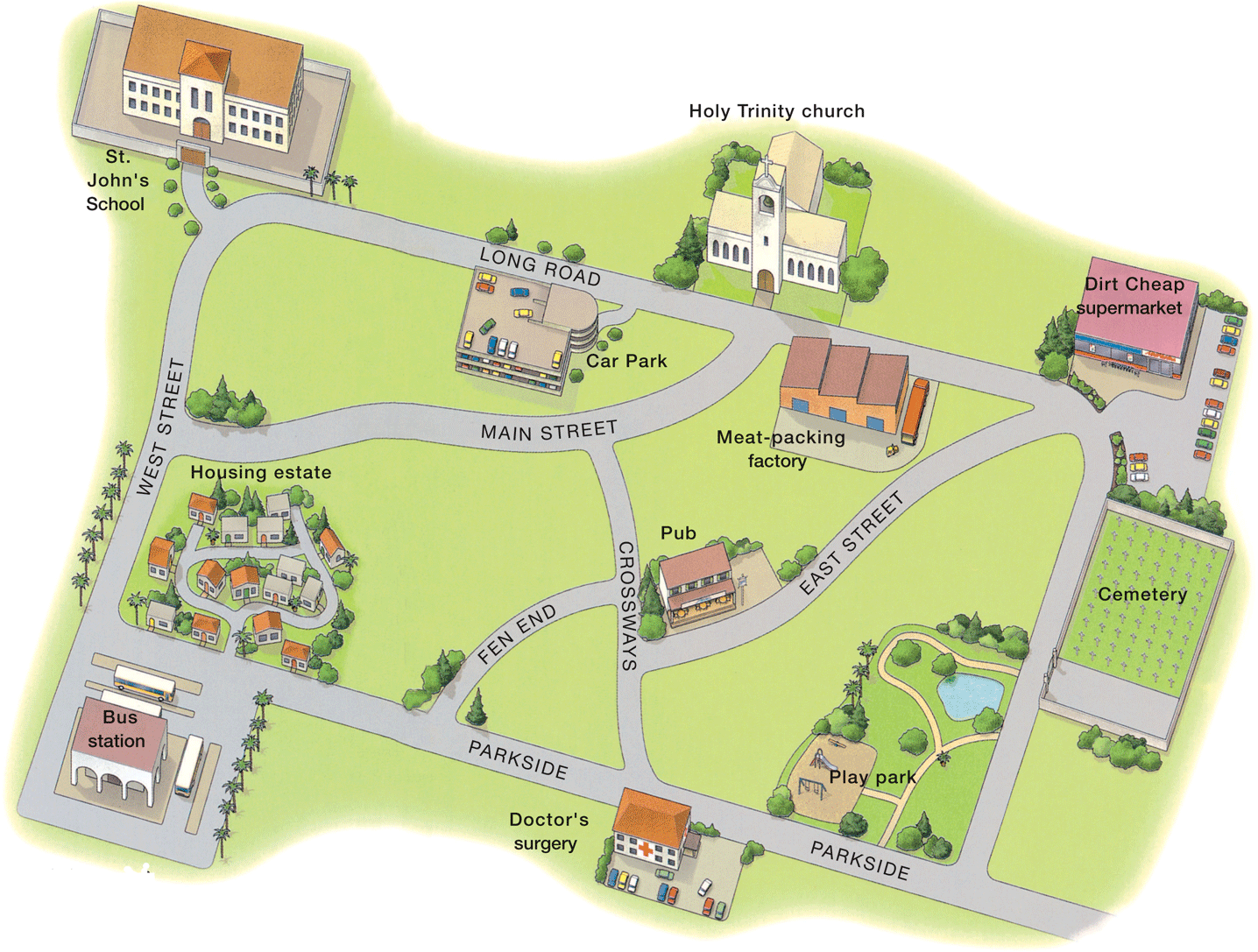

SHORT-TERM MEMORY TASK 5

Map memory

TIME: 10 minutes LEVEL: Medium

This test is about more than just visual memory (though that helps). The map contains a lot of diverse information (names, directions, objects). First, have a go at the whole map. Study it for three minutes, then cover the page with a piece of paper and try to answer the questions below. My guess is that you won’t know many of the answers. Now study the map for a further seven minutes and, this time, draw the map and add the annotations to it as you go. Learn the main outlines first and, once you can draw these without error, start to add further details until you get the whole thing right.

1 What is the name of the church?

2 Which road runs from the church to West Street?

3 Which road connects Fen End and East Street?

4 What is situated in the south-west corner of the map?

5 What is situated north of the cemetery?

6 On which road is the pub situated?

7 What lies at the south end of Crossways?

8 In which road is the multi-storey car park?

9 What lies between West Street and Fen End?

10 What is situated at the extreme eastern edge of the town?

11 What is the town’s main industrial concern?

12 What is the name of the school?

13 Which roads would you follow from the doctor’s surgery to the cemetery?

14 What lies at the north end of West Street?

15 What is the quickest route from the doctor’s surgery to the church?

How did you do?

If you really got all the questions right after only ten minutes’ study, you are ready to become a professional poker player! The trick is to build up your memory bit by bit, filling in extra details as you go. Of course, if you were learning the layout of a real town, it would also make sense to get on your bike and ride around the streets so that you could learn them from personal experience.

If you had great difficulty with this task, don’t worry, it is rather a tough one. Take your time and come back to this page later on. The good thing about memory is that practising a task like this will have a direct effect on your ability to perform other memory tasks. If you keep working at it, you will soon be able to commit material to memory quickly, accurately and painlessly

Remember this!

Learn to draw the town grid first, then practise putting in the road names followed by the buildings (working in a clockwise direction).

The advantage of a bad memory is that one enjoys several times the same good things for the first time.

Friedrich Nietzsche

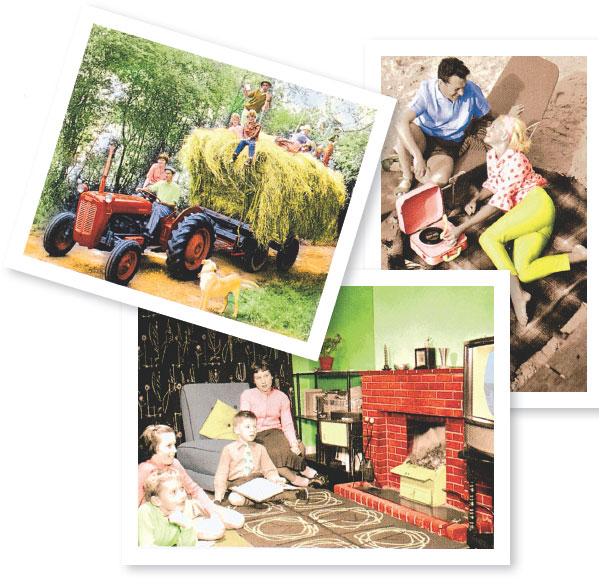

LONG-TERM MEMORY TASK

The good old days

Here’s a test of your long-term memory. This is one area where older people tend to excel. Youngsters, whose brains are firing on all cylinders may, even so, find it harder to recall the distant past than their elders.

1 What was your grandmother’s full name?

2 What was the address of the house you were born in?

3 What was your first cuddly toy called?

4 What was your favourite meal when you were a child?

5 What was your nickname at your first school?

6 What did your grandfather do for a living?

7 What did your grandfather look like?

8 Think of a present that you were given when you were under five years old.

9 Visualize the house you grew up in. What colour was the front door?

10 Who lived next door to you when you were little?

11 Can you picture your first day at school? What did you wear?

12 Who was your first teacher?

13 What was the naughtiest thing you did when you were little?

14 What is your earliest memory?

15 Who did you sit next to in school when you were eleven years old?

16 Which teacher did you really dislike intensely?

17 Can you still remember any poem, speech or reading you learnt by heart at school?

18 Who was the first person you had a crush on?

19 Who was the first person you dated?

20 Who first broke your heart?

21 Who was your best friend when you were eleven?

22 What is the first holiday you remember?

23 What are your earliest memories of Christmas (or other appropriate religious holiday)?

24 Describe a favourite toy.

25 When did you learn to ride a bike?

26 Who taught you to swim?

27 Who was your first real friend?

28 What was your favourite childhood game?

29 What was your favourite TV programme when you were five?

30 What was the first record you ever bought?

31 What was your nickname at school?

32 Do you have sharp pictures in your mind of events from the distant past?

33 Is there a smell that brings back particularly vivid memories for you?

34 What was your first pet called?

35 How many of your cuddly toys can you name?

36 Can you recall any of your birthday parties (below the age of eleven) in detail?

37 What was your favourite song when you were under five?

38 Did you have a gang when you were under eleven? Who else was in it?

39 Can you remember any near misses you had as a kid (such as a road accidents)?

40 What was your most serious childhood illness?

41 Do you have one favourite memory (from your whole life)?

42 Is there one childhood friend you long to meet again?

43 Can you still remember stuff like science formulae that you learnt for exams?

44 Do you remember times long past more easily than recent events?

45 Can you remember where you were when you heard of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales?

How did you do?

The majority of people will have done well in this test and answered over 30 of the questions. What’s more, it is likely that as you started to answer the questions, you were prompted to remember more and more. This mood of reverie may persist for quite some time. It might even prompt you to do things such as getting out old photos and souvenirs, phoning old acquaintances, or even trying to trace people you have lost touch with. Once you stimulate long-term memory, it becomes hugely powerful. You may well be startled at the amount of detail you store in your memory. I have found that just writing out the questions has released a powerful set of images from my childhood, and I can smell creosote on old wood heated in the sunshine - a smell I always associate with summer as a child.

How do we memorize?

Do you remember your first and last days at school? Almost certainly. Do you remember what you had for lunch a week ago? Almost certainly not. We only remember things that stick out in our memory.

I love that bit in cop films when the detective says to a suspect, ‘What were you doing on 28 June at around six o’clock?’ The suspect answers and then the detective trips him up with some well aimed information. Do you remember what you did last Thursday? Of course you don’t. For something to be memorable, it must be made to stick out from the mass of completely forgettable detail that surrounds us. Think, for a moment, of all the information that passes in front of you every day. Think of all the cars, buses, trucks and people you see on your way to and from work. Can you remember any of them? No, normally not. But on the day there’s an accident, you may well remember that it was a blue Mercedes driven by a guy in a red T-shirt that ended up on the wrong side of the road wrapped around a concrete lamp-post.

Memorization is simply a matter of making something stick in your mind. How do you make something stick? You use glue, of course! Memory is just another sort of glue. In fact, it is many sorts and, because you want to remember things for different amounts of time, you need different strengths of glue.

Here is a quick rundown of the methods we’re going to use and a summary of what they are good for. We will look at each method in detail later.

Repetition

This is the weakest glue. Saying something over and over will make it stick in your mind for a very short while, then you’ll forget it again. This is great for, say, a telephone number that you need just once.

Physical reminders

A physical reminder is something such as tying a knot in the corner of your handkerchief to help you remember. All little kids have done this at some time but, just because it’s used by little kids doesn’t mean that it won’t work for you. It will. This method, however, works only briefly (which is all it was meant to do). It will remind you to pick up the kids from school, or take the car to the garage to be fixed, or pick up your dry-cleaning. Once it has accomplished the task, you get rid of it.

Ritual

This is a very weak glue that we use for a quick reminder. When she was too young to set her own alarm clock, my cousin had a system to ensure that she woke up at the right time. Before she got into bed, she’d turn around three times and each time she did it, she’d tap herself on the head and say, ‘Six-thirty! Six-thirty! Six-thirty!’ Then she’d jump into bed and yell, ‘Goodnight world, see you at six-thirty!’ It never failed. There are more complicated and useful ways to make ritual work for you.

Narratives

I must be honest and admit that I never use this method. But that’s no reason to leave it out of the book. I know people who swear by narratives. The method involves making up simple stories that connect a string of objects or facts to be remembered. For example, if you want to remember the telephone number 5231870, you could use a bit of imagination and turn it into, ‘At five to three I ate seven cookies.’ The trouble is that most information you’ll want to memorize will need quite a leap of imagination to turn it into a narrative. I hope it works for you but, personally, there are techniques I like much better.

Association

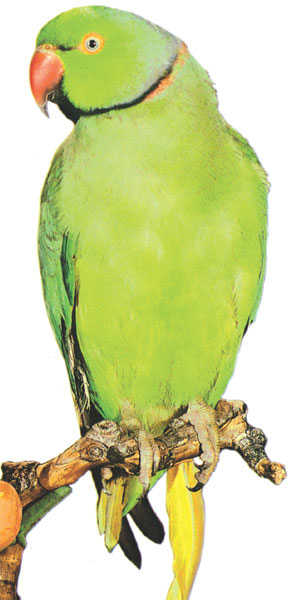

For some crazy reason, it is easier to remember a thing if you associate it with another thing. For example, I could never remember the word ‘cyclamen’ (it’s a plant, some people call it rabbit’s ears). Then I noticed that the leaves look a bit like little wheels, so I called the plant ‘cycling men’ and now I never forget. Associations are good for remembering odd bits of simple information.

Mnemonics

A mnemonic is just a simple device to help you remember. It often, but not always, depends on the initial letters of words to be memorized, such as HOMES for the Great Lakes of America (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Eyrie, Superior); or Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain for the colours of the rainbow (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet). Mnemonics are a strong glue and very useful. They help us remember a lot of stuff that is a drag to look up, and which we need to recall from time to time.

Rhythm and rhyme

We’ll use rhythm and rhyme to cover both metre (as used in poetry) and music. You can use both of these to remember a wide variety of things. Beware! This is a very, very strong glue. Anything you remember this way will stay with you for life. When I was young, I memorized all my physics formulae to the tunes from Bizet’s Carmen and now, forty years later, I still can’t listen to that music without recalling stuff about amps and volts.

Visualization

This is also a strong glue, which is used for things such as remembering faces, diagrams and pictures. It can also be used in other very important ways that will be explained later.

Kinaesthetics

You learn to play a musical instrument by using your sense of touch. Your fingers remember the correct positions and pressures. Also, you can reinforce other memories by adding some sort of motion to them. For example, some people beat out time while memorizing. You might not want everyone to see you do this (they might just get the wrong idea about your sanity), but it does work.

Learning it parrot fashion

Repeat after me: 0795634. Say it again, and again, and again. If you work at it for a couple of minutes, you’ll find that the memory sticks - but not for long. It’s doubtful whether, without using some other method, you would be able to remember those numbers this time tomorrow. But that’s OK because there are some things we just don’t want to remember for very long. So, if you look up a phone number and want to remember it just long enough to get to the phone and punch the buttons, repetition is a good technique. If, however, you’ve just met someone you think might become the love of your life and have been given his or her phone number, this is not a safe way to commit it to memory.

PLAY IT AGAIN, SAM

Memories that you want to keep fresh should be reviewed regularly. After you have used the techniques in this book for a while, you’ll build up a library of memories and, from time to time, you need to test yourself again. You can do this in any scrap of spare time you have, for example while travelling to work, or even while doing some other task such as mowing the lawn or cooking dinner. This reviewing procedure needn’t be boring and can actually be quite a good way to relax and forget the stresses of the day.

When my kids were really young, they would prepare for spelling tests by repeating the spellings until they got them all right. In those days, I knew less about memory than I do now, so, because I’d been taught to learn my spellings parrot fashion as well, I went along with it. The result? They both got excellent marks in their spelling tests, BUT by the next week they had forgotten everything they’d supposedly learnt.

Repetition forms part of all the other techniques you will learn and, used in combination with those techniques, it is very powerful; on its own it is only a temporary fix.

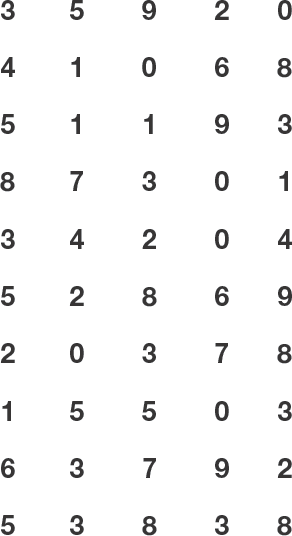

As an experiment, we’ll see just how many digits you can commit to memory using ONLY the repetition method. Here’s a series of 50 digits in groups of five.

There is another important use for repetition, however, and that is in getting other people to remember something. I used to study Spanish at a local community college. People came from surrounding villages; one of which was called Over. Every time anyone mentioned that they came from Over, the teacher would say ‘sobre’ (the Spanish for ‘over’). He said it every lesson and, by the end of the year, if there was one word of Spanish that everyone remembered permanently it was ‘sobre’. The limitation of this technique is that you can only get people to remember things they want to remember. If you repeat something they don’t want to remember, it’ll just bounce off like water off a duck’s back. For example, I frequently tell my kids to tidy up and turn off TVs, hair straighteners, CD players, lights and so on before they go to school. Several thousand repetitions have so far failed to do the trick.

Remember, the rule is that you must only use repetition to memorize these numbers. See how many you can remember and how long you can retain your sequence. You’ll probabiy be disappointed, but don’t worry - this is only a minor way of memorizing.

A memory is what is left when something happens and does not completely unhappen.

Edward de Bono

God gave us memories that we might have roses in December.

J. M. Barrie, Courage

There’s always something there to remind me

When you were young, you may have had quirky tricks, such as tying a knot in the corner of your handkerchief to help you remember simple tasks or chores. Physical reminders like this are a quick and easy way to get you to remember something simple that might otherwise slip your mind. The hanky knot is invaluable for reminding you to take your kids to the dentist. Some people use methods such as a rubber band wound around one finger (rather uncomfortable and too obvious) or a sticking plaster covering a nonexistent cut.

Physical reminders can be extended from your person to your surroundings. Leaving some familiar object out of its normal place can act as a memory trigger. For most of us, this technique can work at a simple level (car keys left on the coffee table (instead of on the key rack) can tell you to take the car for servicing), but if you leave too many reminders around they might become confusing. Some families get so used to communicating in this way, that they leave quite complicated ‘notes’ for each other that no one else could ever understand. For example, someone might leave a stone misplaced near the front door to tell other family members that a spare set of house keys has been hidden in the potting shed. Cunning, eh?

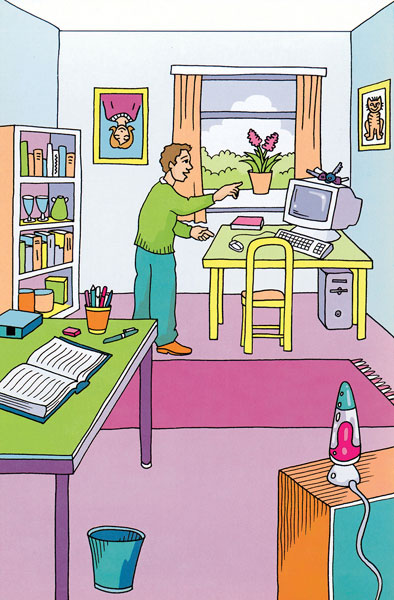

This is Jim’s house. The book lying open on his desk is to remind him to go the library. The car keys have been left on top of the computer to remind him to get the car serviced, and the picture of his wife is upside down, not because he’s careless, but because tomorrow is her birthday and he must remember to buy her a present.

ATTACK ON ALL FRONTS AT ONCE

Don’t use just one technique to remember something - try to use several. Looking, listening and doing methods should all be combined for the best result. For an example of how to do this, go to ‘Learn the kings and queens of England’ and look at the hints there.

Memory is a child walking along a seashore. You never can tell what small pebble it will pick up and store away among its treasured things.

Pierce Harris, Atlanta Journal

We do not remember days; we remember moments.

Cesare Pavese, The Burning Brand

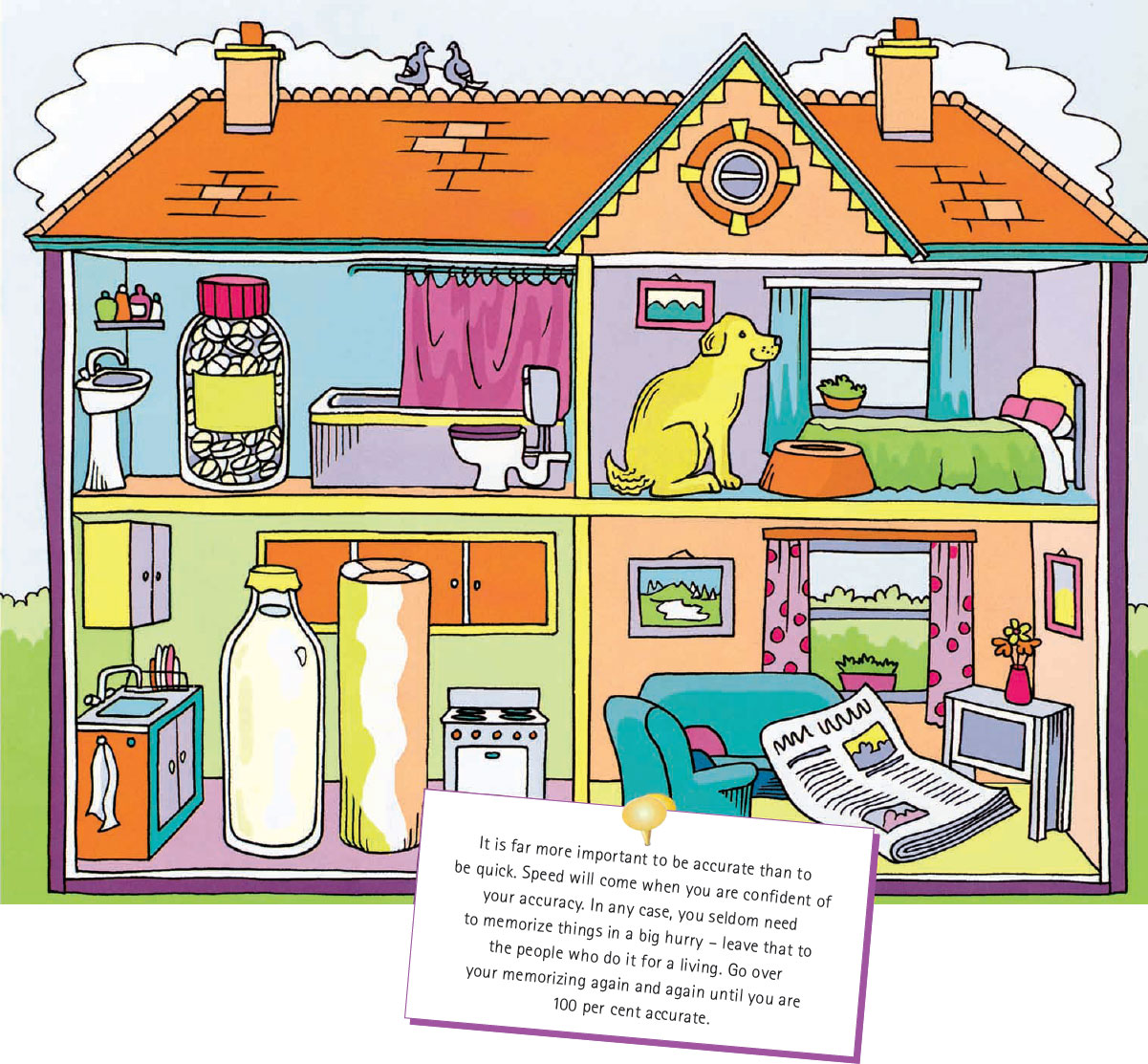

It’s all in the mind

Can you visualize your house? Yes, almost certainly you can. You probably know every nook and cranny of it and could find your way around blindfold. This is what makes it an excellent device for memorizing.

Let’s say you are going shopping. One way of remembering the things you need to buy would be to imagine the objects around the house. For example, a newspaper lying on your virtual kitchen table will remind you to go and buy The Times. You can strengthen the memory bond by making the objects appropriate to the places they are left - a bag of sugar near a photo of your little daughter (isn’t she sweet?) and a bag of lemons next to the photo of your mother-in-law ...

Give it a try. Take the following list and place the items in your virtual house (or another place you feel comfortable with):

Newspaper

Painkillers

Chocolate bar

Milk

Sugar

Cookies

Apples

Potatoes

Breakfast cereal

Sticking plasters

Weedkiller

Fertilizer

Guitar strings

Oranges

TV listings

magazine

Barbecue charcoal

Cut flowers

Knitting wool

Sausages

Toothpaste

Check through your list several times until you’re sure you can remember every item clearly. Always walk around your virtual house in the same order. This adds a very important element of ritual to your memorizing.

I want to tell you a story

One way of remembering things is to combine them into a silly story. Note the word ‘silly’. The sillier the story, the more likely you are to remember it. For example, using the items pictured, you could come up with something like this.

I was waking on stilts (that looked like hockey sticks)

when I lacrossed the road and tripped over a heap of tennis balls.

My intentions were foiled because I crashed into a fence,

which made an enormous racket.

After that I needed some tea,

so I went to my club to wait (weight).

No one offered me a lift so I ran home,

which left me feeling full of bounce.

KEEP IT WACKY

You don’t remember sensible things because they’re just too boring. You do remember wacky things. Use wild associations, crazy rhymes, and weird visual images. My father taught me the alphabet by getting me to sing it to the tune of the Ode to Joy from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. You think that’s a crazy thing to teach a little kid? I loved it! Try singing it in the shower and you’ll see what I mean.

Stupid? Undoubtedly. But memorable. Try it out for yourself. Come up with your own story and I bet that within a few minutes you’ll be able to remember the whole list without omitting a single item.

The only problem with this method is that it does confine you to remembering all the items in the same order. If someone asked you, ‘Does the tennis racket come before or after the golf clubs?’, you’d probably have to run through the whole story to make sure.

Memory is a complicated thing, a relative to truth, hut not its twin.

Barbara Kingsolver, Animal Dreams

Rhythm and rhyme

When no one’s listening, try singing the nursery rhyme ‘Jack and Jill Went Up the Hill’. Go on! Just for me. One thing I’ll guarantee, you haven’t forgotten the words or the tune. That’s because rhythm and rhyme are very, very, very strong memory glue. If you want to remember something forever, set it to music with a good, strong rhythm. In olden times, the bards would not just tell old stories, they would sing them. That’s how they remembered all those interminable tales of heroes, gods and beautiful maidens. If I ask you to tell me a well-known story like, say, Peter Pan, you’ll probably be able to give me a précis; but the whole thing, word for word? I doubt it. But you can learn huge chunks of Shakespeare by heart because that’s poetry and the rhythm helps you, even though much of the language is unfamiliar.

Some people complain about being made to learn poetry by heart at school, but I loved it. Have a go at Walter Scott’s ‘Lochinvar’. What, all of it? Yes, why not? You’ll find that because it is real old-fashioned poetry with strong rhythm and rhyme, you’ll memorize it easily and, more to the point, permanently.

Instructions

![]() There is no magic trick to learning things that come with rhythm and rhyme built in. The fact is that our minds naturally store anything that comes in this form. That’s why kids can learn endless pop songs and be word perfect in all of them.

There is no magic trick to learning things that come with rhythm and rhyme built in. The fact is that our minds naturally store anything that comes in this form. That’s why kids can learn endless pop songs and be word perfect in all of them.

![]() All you have to do is split the thing into chunks (the Scott poem works in couplets, so that’s the best way to learn it).

All you have to do is split the thing into chunks (the Scott poem works in couplets, so that’s the best way to learn it).

![]() Just keep going over it until the rhythm and rhyme embed themselves in your memory.

Just keep going over it until the rhythm and rhyme embed themselves in your memory.

The past is never dead, it is not even past.

William Faulkner

A happy childhood can’t be cured. Mine’ll hang around my neck like a rainbow, that’s all, instead of a noose.

Hortense Calisher, Queenie, 1971

Lochinvar by Sir Walter Scott

O young Lochinvar is come out of the west,

Through all the wide Border his steed was the best;

And save his good broadsword he weapons had none,

He rode all unarm‘d, and he rode all alone,

So faithful in love, and so dauntless in War,

There never was knight like the young Lochinvar.

He staid not for brake, and he stopp’d not for stone,

He swam the Eske river where ford there was none;

But ere he alighted at Netherby gate,

The bride had consented, the gallant came late:

For a laggard in love, and a dastard in war,

Was to wed the fair Ellen of brave Lochinvar.

So boldly he enter’d the Netherby Hall,

Among bride’s-men, and kinsmen, and brothers and all:

Then spoke the bride’s father, his hand on his sword,

(For the poor craven bridegroom said never a word),

“O come ye in peace here, or come ye in war,

Or to dance at our bridal, young Lord Lochinvar?”

“I long woo‘d your daughter, my suit you denied;

Love swells like the Solway, but ebbs like its tide

And now I am come, with this lost love of mine,

To lead but one measure, drink one cup of wine,

There are maidens in Scotland more lovely by far,

That would gladly be bride to the young Lochinvar.”

The bride kiss’d the goblet: the knight took it up,

He quaff’d off the wine, and he threw down the cup.

She look’d down to blush, and she look’d up to sigh.

With a smile on her lips and a tear in her eye,

He took her soft hand, ere her mother could bar,

“Now tread we a measure!” said young Lochinvar.

So stately his form, and so lovely her face,

That never a hall such a gailiard did grace;

While her mother did fret, and her father did fume

And the bridegroom stood dangling his bonnet and plume;

And the bride-maidens whisper’d, “’twere better by far

To have match’d our fair cousin with young Lochinvar.”

One touch to her hand, and one word in her ear,

When they reach’d the hall-door, and the charger stood near;

So light to the croupe the fair lady he swung,

So light to the saddle before her he sprung!

“She is won! We are gone, over bank, bush, and scaur;

They’ll have fleet steeds that follow,” quoth young Lochinvar.

There was mounting ‘mong Graemes of the Netherby clan;

Forsters, Fenwicks, and Musgraves, they rode and they ran:

There was racing and chasing on Cannobie Lee,

But the lost bride of Netherby ne’er did they see.

So daring in love, and so dauntless in war,

Have ye e’er heard of gallant like young Lochinvar?

GIVE ME A BREAK!

It is important to take breaks during a memorization task. The mind works in mysterious ways, and one of them is that it keeps on working even when you think it has stopped. If you start a task today, and then stop and get a night’s sleep, you’ll find that during the night your mind has been mulling over the memory and by the next day. Your performance will have improved. If you don’t take breaks, you’ll get tired and stale and your task will be longer and more arduous.

I can see it all!

Some people are born visualizers. Their imagination is full of vivid pictures and vibrant colours. My visual memory, on the other hand, looks like a collection of rather faded picture postcards. If you have a really good visual memory, you can make use of it in a number of ways. One of them is to play Memory Lane.

Think of the street where you live (or any other street that you know really well). In your mind’s eye, walk down the street depositing items that you want to remember in all the front gardens. You can include just about anything. In our illustration the man is reminding himself to take an umbrella when he goes to work (rain is forecast), get in a round of golf when he comes home, and buy butter, sugar and tea. There’s a list of ‘Things To Do’ outside the local shop. Finally, he reminds himself to go to a friend’s party where he will book tickets for Hawaii (his friend is in the travel business and gets him a discount).

You can extend this technique as much as you like. Some people, for example, learn dates by mentally carving them on a stone timeline. Another use for visual memory is in remembering faces and places. If visual memories work for you (there’s no particular trick to doing it), you just have to remember to do it! If you’re visiting a new town for the first time, make sure you keep a visual record of the route you take through the town so that you can find your way back to where you parked the car.

Divide and conquer

Never attempt to memorize large chunks of material in one go. Split large tasks into smaller elements. If there is a natural split (the stanzas of a poem, for example) it is helpful, but if not, just create an artificial division to suit yourself. To see this technique in action, look at ‘Presidents of the USA’.

In memory’s telephoto lens, far objects are magnified.

John Updike

Learning by doing

For some people, the very best way to learn about something is to go and do it. They get more information from that than they would from any amount of book learning. This ability lends itself to a whole area of memory techniques based on doing, which are sometimes called ‘kinaesthetic techniques’.

When I was young, I went to a school that had strong views about pupils bringing the right books and equipment with them for lessons. The words, ‘Sorry, I forgot’, were not met with a smile. So, how did I manage to avoid trouble? I constructed a ritual for filling my school bag every evening. It was very complicated, but that was precisely the reason it worked. Not only did each book and item of equipment have its own place, but each one had to be put in the bag in the correct order. It soon became a virtual impossibility to forget anything, because if I did, the ritual didn’t feel right and I’d soon spot my oversight.

That is one sort of ritual, but there are other much more complicated and useful ones.

When something that we do regularly is considered important, one way of making sure it all goes to plan is to turn it into ritual. Churches have been good at this for centuries. So have other institutions such as monarchies. A nice bit of ritual binds the community together and reminds everyone of their place in the grand scheme. But how is this relevant to your quest for a better memory?

The army is often derided for teaching people to do things by numbers. But this is actually a very good and practical use of ritual. How else would you teach a youngster who has little formal education (and may not be too bright) to strip down a complicated device such as a machine gun, correct a jammed mechanism, and put it all back together again, without losing any of the pieces? Ritual, that’s how. Once they learn to do it by numbers, they will never forget, even when under fire and in a highly stressed state. It has become impossible to leave out one of the numbered stages.

ORDER, ORDER!

When you learn a list of things (telephone numbers, for example) make sure that you frequently change the order in which you rehearse them. If you don’t, there is a strong risk that you will be committing the order itself to memory. If that happens, you will find that you have to go through the whole list every time you want to find one item. So, when you rehearse your list, mix it up so that the order never forms part of your memory pattern.

The past is malleable and flexible, changing as our recollection interprets and re-explains what has happened.

Peter Berger

There are lots of people who mistake their imagination for their memory.

Josh Billings

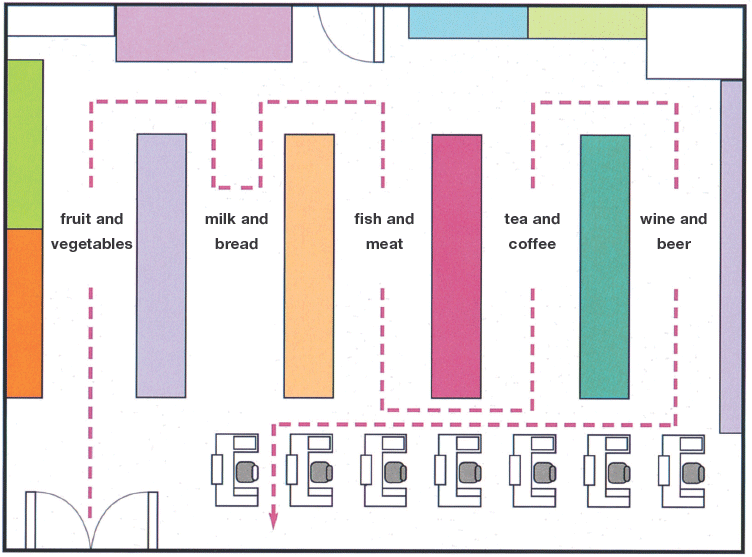

Supermarket routines

My wife has another sort of ritual. When she visits the supermarket she always makes exactly the same tour. Most of us buy more or less the same stuff each week, but with some changes (for example, you probably don’t need razors every week). But once you’ve committed the order to memory, you no longer have to think about it and can concentrate your energy on remembering any changes to the usual routine (for example, maybe this week you fancy wine instead of beer). You can extend your ritual to cover not just the supermarket, but all the other places you normally have to visit. The ritual makes it very unlikely you’ll forget anything important. Some people might object that shopping this way is rather boring and mechanical. To counter that, we save the fun stuff (new clothes, CDs, etc.) until last so that we can enjoy them at our leisure.

Don’t knock ritual! It is an effortless way to remember complicated information without mistakes. Think, for example, of how you drive a manual car. Do you consciously think: apply brakes, slow down, change gear, check mirror, look both ways at junction? No, of course you don’t. Once you can drive, the whole process becomes automatic. No matter what the circumstances on the road, the appropriate ritual will cut in. The only time you’ll be flummoxed is if you get into a violent skid and haven’t bothered to learn the technique for dealing with a skid safely.

The gentle touch

Do you remember showing some new possession (a camera, for example) to a friend for the first time? He says, ‘Oh, let’s have a look!’ and takes it from you, apparently to look closer. But as well as looking, he is also feeling. For some reason, we are a bit coy about our habit of learning through touch. We actually would like to touch all sorts of things (especially other people) just to get to know them better, to quite literally get a feel for them. The sense of touch is delicate but also very powerful.

Touch does not just inform us of things that are going on right now, but it also involves a specialized kind of memory. A blind friend once showed me how he could run his fingers over the cards in a pack and identify many of them just by the way they felt: odd irregularities, creases and bent corners, which would be just about invisible to a sighted person, were picked out unerringly by his heightened sense of touch.

Although our sense of touch is innate, like all other senses it can be improved by practice. You need to spend some time quite deliberately feeling objects and trying to identify them just from touch. Some work depends entirely on a well-developed touch memory: For example, a bomb disposal officer is trained to do this sort of work largely by the memory of how things feel. It is not always possible to open up a bomb and take a good look inside, so he needs to be able to feel his way around. A touch in the wrong place could put a very sudden end to his career.

It’s surprising how much memory is built around things unnoticed at the time.

Barbara Kingsolver, Animal Dreams

To look backward for a while is to refresh the eye, to restore it, and to render it the more fit for its prime function of looking forward.

Margaret Fairless Barber, The Roadmender

Eidetic memory

What used to be called photographic memory is now known by the term ‘eidetic memory’. Some people can look briefly at an object, design or document and then reproduce it in minute detail, just as though their mind had taken a photograph of it. As you would imagine, there is huge controversy surrounding this whole topic. Some psychologists are strong believers in eidetic memory, whilst others have doubts, or even deny that there is any such phenomenon.

It seems beyond question that certain individuals do have a greater-than-average ability to remember things they have seen. One of my aunts, who was trained as a dressmaker, had the useful ability to copy any dress after looking at it for only a very short time, She built up a thriving business turning out imitations of dresses she had seen pictured at society weddings, or worn by film stars. A flick through the pages of the gossip magazines or, better still, a few minutes spent in the presence of the actual dress, and she could make you a perfect copy

The point is, could you learn to do this; or do you have to be born with the ability? Let’s see! The drawings on these pages start out as quite simple, but get increasingly complex. Look at each drawing (for as long as you need). Then put the book aside and try to reproduce the drawing in as much detail as possible.

TRAIN YOUR EIDETIC MEMORY

There are numerous free computer games, available on the Internet to help train your eidetic memory. Simply search under the words ‘eidetic memory training’ and you will find a wide choice of programs on offer.

One of the most moving aspects of life is how long the deepest memories stay with us. It is as if the individual memory is enclosed in a greater, which even in the night of our forgetfulness stands like an angel with folded wings ready, at the moment of acknowledged need, to guide us back to the lost spoor of meaning.

Laurens Van Der Post

Our memories are card indexes consulted, and then put back in disorder by authorities who we do not control.

Cyril Connolly, The Unquiet Grave

Mozart memories?

Much has been written about the so-called ‘Mozart effect’ and the whole area has been infected by controversy and commercialism. I don’t want to argue about whether little kids can have their IQs boosted by listening to Mozart, simply because it is not relevant to our purpose. What I do want to discuss is whether any sort of music can aid concentration and memory.

Many people like to use music as a background to any sort of work. Runners in the park, kids doing homework, workers on assembly lines and shoppers in supermarkets all receive a daily dose of background music. I regularly visit the design studio of one of my publishers and see the designers hunched over their Macs, each in his or her own private world of music. But does the music help or distract?

What follows are my personal views and I make no claims other than they are based on my own experiences, and those of my family and students I have worked with in my creative writing classes. If you disagree, feel free to do so and listen to whatever you please. If it works for you, it works.

The only thing I would absolutely advise against, when trying to memorize, is having a TV on anywhere near you. If you can see it, you will not be able to concentrate on the work in hand. Even the most witless game show or soap looks entrancing when the alternative is to do some work. If you can only hear the Tv, it’s not much better - you’ll be wondering, even if only at the back of your mind, what is happening on screen. You’ll almost certainly give in at some point and go to take a quick peek. You may return to your work (or not), but in any case your concentration will be broken.

Don’t just memorize at odd moments. Plan a session, decide how long it will last and what you will achieve. Decide when you will take a rest.

Music is far more a matter of personal taste. My kids swear that they can revise to the strains of heavy rock. I’m sure that you can do some tasks to music but I doubt that you can marshal all your concentration when you are listening to something loud and lively. Having said that, I must confess that I’m writing this to the strains of Pink Floyd, and my concentration is unbroken so far.

So how about classical music? Like many people, I enjoy popular classics. I can happily listen to The Four Seasons or Scheherazade, but it’s not the sort of music I’d choose to work to - until recently, that is. I read an article about the way in which classical music (any classical music) could increase your concentration and improve memory. Since it was strictly relevant to this book I gave it a try and, to my surprise, it worked very well indeed. I recommend it to you. You don’t even have to like the music. But it does create a calm atmosphere where you will find concentration easier and where memories will stick. And the quicker you learn, the sooner you can get back to the TV.

Every day your memory grows dimmer/ it doesn’t haunt me like it did before.

Bob Dylan

You are not a computer

Some people maintain that the brain works like some sort of super-computer. They even talk about removing faulty programs and replacing them with new, improved ones. Piffle! The brain is not at all like a computer. Don’t be fooled into believing this sort of nonsense. Your memory works in a mysterious and highly complex fashion. It needs careful training and maintenance. You do NOT have a hard disk in your head. Here are the main differences between the way you memorize and the way a computer does it.

It is singular how soon we lose the impression of what ceases to be constantly before us. A year impairs, a lustre obliterates. There is little distinct left without an effort of memory, then indeed the lights are rekindled for a moment - but who can be sure that the Imagination is not the torch-bearer?

Lord Byron

Computer

![]() No sense of humour

No sense of humour

![]() 100 per cent recall on hard disk, floppies and CD-ROM

100 per cent recall on hard disk, floppies and CD-ROM

![]() Can share memories with other computers

Can share memories with other computers

![]() No visual memory (but can recognize photos when encoded)

No visual memory (but can recognize photos when encoded)

![]() No emotional reaction to memory

No emotional reaction to memory

![]() No creativity

No creativity

![]() Will only recall what the human operator asks for

Will only recall what the human operator asks for

![]() Unable to memorize smells

Unable to memorize smells

![]() Memories are in no particular order of importance

Memories are in no particular order of importance

![]() Very limited ability to learn from experience

Very limited ability to learn from experience

![]() Does not learn by touch - Requires no rest

Does not learn by touch - Requires no rest

![]() Requires no food (but needs electricity in order to function)

Requires no food (but needs electricity in order to function)

![]() Has no emotions

Has no emotions

![]() Will recall any memory upon request

Will recall any memory upon request

![]() All memories remain just as they were when recorded

All memories remain just as they were when recorded

Human

![]() Sense of humour (in most models)

Sense of humour (in most models)

![]() Fallible and capable of forgetting even important data

Fallible and capable of forgetting even important data

![]() Able to share memories with other humans

Able to share memories with other humans

![]() Strong visual memory

Strong visual memory

![]() Memory used to spark off creative tasks

Memory used to spark off creative tasks

![]() Quirky memory that recalls data not asked for

Quirky memory that recalls data not asked for

![]() Memorizes smells

Memorizes smells

![]() Memories are roughly ranked according to importance

Memories are roughly ranked according to importance

![]() Learns greatly from experience

Learns greatly from experience

![]() Can learn complicated tasks by touch alone

Can learn complicated tasks by touch alone

![]() Must sleep or die

Must sleep or die

![]() Has complicated dietary requirements that can affect memory

Has complicated dietary requirements that can affect memory

![]() Memories are strongly linked to emotions

Memories are strongly linked to emotions

![]() May resist recalling painful memories

May resist recalling painful memories

![]() Can add sentimental gloss to memories (the ‘Good Old Days’ effect)

Can add sentimental gloss to memories (the ‘Good Old Days’ effect)

TESTING, TESTING, TESTING

It is very easy to convince yourself that you remember something when you are really not yet word-perfect. To get over this difficulty, you should get someone to test you whenever possible.

Inability to remember

If you find yourself unable to retain information, there may be several possible reasons. The main one is usually stress. You will never be able to memorize if you let yourself get stressed. Memory is like sex - you have to be in the right mood, and that means feeling happy, relaxed and enthusiastic about what you are doing.

![]() Do NOT leave revising to the last minute. Start in good time and do a little - thoroughly - each day. It is far better to learn a little bit well than to try to cram in a whole lot and make a mess of it. To get it all done on time, you must plan your revision well.

Do NOT leave revising to the last minute. Start in good time and do a little - thoroughly - each day. It is far better to learn a little bit well than to try to cram in a whole lot and make a mess of it. To get it all done on time, you must plan your revision well.

![]() Do things to ensure you’re in a good mood. Have some snacks and drinks (non-alcoholic) nearby to reward yourself for your efforts. If you like music, put some on at a low volume (you won’t revise properly if you have to contend with loud music).

Do things to ensure you’re in a good mood. Have some snacks and drinks (non-alcoholic) nearby to reward yourself for your efforts. If you like music, put some on at a low volume (you won’t revise properly if you have to contend with loud music).

![]() Make sure that you are not too warm or too cold.

Make sure that you are not too warm or too cold.

![]() Allow plenty of fresh air into the room. A stuffy room makes you drowsy and messes up your ability to concentrate.

Allow plenty of fresh air into the room. A stuffy room makes you drowsy and messes up your ability to concentrate.

![]() Keep other members of the family away and get someone to answer the phone and take messages for you.

Keep other members of the family away and get someone to answer the phone and take messages for you.

![]() To revise successfully, you need to concentrate for at least half an hour to an hour. Too little will do you no good and too much will make you stale. After each session, take a break. When you are revising hard for an exam, you can get in three or four one-hour sessions a day, then go out and do something completely different.

To revise successfully, you need to concentrate for at least half an hour to an hour. Too little will do you no good and too much will make you stale. After each session, take a break. When you are revising hard for an exam, you can get in three or four one-hour sessions a day, then go out and do something completely different.

TRYING TO FORGET

One of the ways in which you differ from a computer is that your memories cannot be deleted at will. Memories that are not reviewed regularly will fade eventually. Memories that are of no further interest (like a once-only telephone number) will vanish without trace. Unpleasant memories have a habit of sticking just because they are unpleasant. The harder you struggle against such memories, the harder they are to erase. My uncle was with troops who liberated a Nazi death camp, and he struggled with the memory for the next forty years.

The only way (and it’s by no means infallible) to deal with such memories is to review them when they resurface.

What’s stopping you?

A major cause of faulty memory is lack of understanding. Certain things can be learnt parrot fashion, whether you understand them or not (though almost any attempt at memorization is improved by understanding). For example, you can learn the dates of all the battles in the American Civil War by rote if you want to. But how much better it would be if you understood the background, who was fighting and why. When you have that sort of framework to hang the information on, it is far easier to make it stick.

Some things just cannot be learnt without understanding them. Science without understanding becomes a jumble of weird symbols and figures. Literature becomes soulless and without meaning. If you master the background to a subject, the information will be easier to assimilate.

If you really can’t remember, despite your best efforts, you need to ask yourself why. Are you studying something you really hate just to please your parents? Are you in a career that no longer interests you? Are you afraid of failing your exams? If there is some unresolved issue that is stopping you from memorizing successfully, then unless you face and resolve it, you will find your efforts constantly frustrated.

Everybody needs his memories. They keep the wolf of insignificance from the door.

Saul Bellow

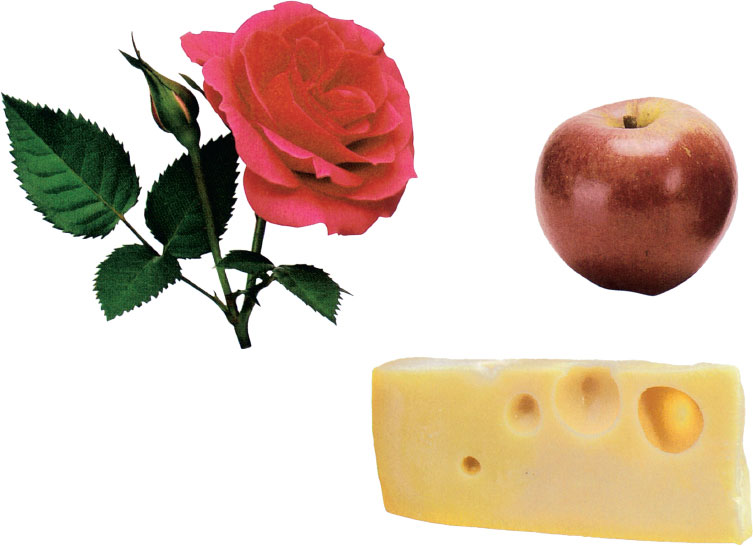

Ah, yes! I remember that smell!

Smell is the strongest memory key of all. This is strange when you consider that, compared to other animals, our sense of smell is quite frail. Nevertheless, we have all had the experience of a sudden aroma taking us back to some place we loved or hated years before. Chalk dust can evoke school classrooms, the smell of chlorine conjures up swimming lessons long past, and strawberries have a smell inseparable from hot summer days.

The smell trigger is highly personal. Although most readers will relate to at least some of the smells given off by the items below (because they are very common ones), we all have our own special triggers. I react strongly to the smell of the herb coriander (cilantro). It reminds me of my time teaching in Thailand, when it was served with virtually every meal. It has a powerful smell which, until I was used to it, I found rather offensive. Then I got to like it, and now the smell reminds me of delicious Thai meals I’ve enjoyed in the past.

It is frustrating that the smell trigger cannot be used to help us store information. It doesn’t provoke the right kind of memory. Smell is closely linked to emotion rather than the recall of facts. It might help you to remember places, people, or things that made you happy, sad, angry, lovelorn, or amused; sadly, it cannot remind you of, say, the names of the Presidents of the USA.

Is there any practical use for the smell trigger? It is useful for creating moods (as anyone who owns an oil burner, or who regularly uses incense, will testify). You could use it as an adjunct to other memorization methods by introducing aromas that you find agreeable and which put you in a relaxed mood.

CONFIDENCE

Probably when someone gives you an address, phone number or any other important information, you rush at once to write it down. Don’t! Learn to have confidence in your memory. The more practice you have at remembering, the more you remember. Have confidence in your ability and you’ll soon find that it is justified.

The sense of smell can be extraordinarily evocative, bringing back pictures as sharp as photographs, of scenes that had left the conscious mind.

Thalassa Cruso, To Everything There is a Season

Ah, yes! I remember it well!

You might remember a number from the musical Gigi in which an old man and his sometime lady-friend recall their first date. He gets all the details wrong and she corrects him but, even so, he always replies, ‘Ah, yes! I remember it well!’ And he does! This is an excellent example of what is now called False Memory Syndrome. I’ll give you another. When I was a boy in Scotland, we used to go to Craiglockhart golf course in Edinburgh for tobogganing. It was five minutes’ walk from my house. I remember the scene vividly. The clubhouse was on the right and the golf course swept away majestically to the left. It was a really excellent place to ride a toboggan. Recently, I went back after forty something years and found the scene exactly as I remembered it. Except for this: the clubhouse was actually on the left and the golf course swept away to the right! It was not that I’d come in from another direction, because I’d found my old house and followed the exact route I’d taken so often as a kid. But there we are - a false memory.

We don’t know a lot about how false memories happen, but research suggests that they can be encouraged very easily. In a recent experiment, volunteers listened to a description of experiences they could not possibly have had (though they were unaware of this). For example, a group of British volunteers were told of an incident in which a skin test was carried out by scraping a sample of skin from the little finger. (This particular technique is simply not used in the UK, though it is common in the US, so there was no way any of these people could have had it done to them.) Some members of the group subsequently went on to form very clear memories of having had such a test taken.

False Memory Syndrome can be simply odd and even quite amusing, but it does have a sinister side. Some psychotherapists have made a fortune helping clients to recover memories of sexual abuse during childhood. Theoretically, these were memories that had been buried deep in the psyche because of the trauma associated with them. Increasingly, however, it seems that a proportion of such patients have simply been encouraged to form false memories of events that never took place.

If you want to see False Memory Syndrome in action for yourself, try this experiment. Ask your family or a group of friends to write a description of an event you shared. It could be a party, a family gathering, or an outing of some sort. Not only will the individuals all remember the event slightly differently, but the chances are that at least one person will come up with a scene that the others are all quite sure never took place.

Nostalgia is like a grammar lesson: you find the present tense and the past perfect.

Anon

The long and winding road

This is an exercise in using your long-term memory. There is nothing you need to do to form this type of memory - it happens automatically. Your unconscious will simply file stuff away without any reference to your conscious desires at all. This can be quite inconvenient. Sometimes you may find yourself desperate to remember an incident from long ago, only to find that you can’t dredge it up. At other times, you’ll find yourself plagued with memories that are either quite useless and distracting or, even worse, decidedly unpleasant.

What to do? It is a good idea, every now and again, to deliberately stimulate long-term memory. There are several ways of doing this and you should use all of them. One is simply to sit and recollect incidents from your past. You can just ramble aimlessly down memory lane if you want to, or you can pick out a specific train of thought (school days, jobs you have held, old friends, former lovers, whatever takes your fancy). Just let your mind meander where it will. The more relaxed you feel, the more likely you are to have a good experience. An extra way of stimulating the flow of memory is to either write your thoughts down (you don’t have to be an expert writer, notes will do just as well), or to recount your experiences to a relative or friend. If you do use someone as a recipient for memories, make sure it is a person who is both willing and trustworthy.

Another way to get the long-term memory centre working is to look through mementoes and photographs, or to visit places that you used to frequent long ago. This is obviously a very powerful stimulant and you’ll probably find that once you do it, the flow of memory will turn into a flood.

Finally, you might try talking to friends, relatives, colleagues and acquaintances from your past. People are often very keen to do this (as can be seen from the success of various websites that encourage people to get back in contact with their former friends).

For most people, there are considerable benefits in keeping their long term memory in good repair. It aids mental health by reinforcing our sense of identity, reassuring us about who we are and how we fit into our own personal life story: It can provide a feeling of warmth and security that is far better than anything you can get from pills.

Just one word of warning - if your life is full of unresolved conflicts, unhappy memories and repressed traumas, you should only carry out this exercise in the company of a trained professional.

To help you begin your journey, try the suggestions below. They will give you some preliminary thoughts that will launch your voyage of exploration in the right direction. We tried a questionnaire a bit like this earlier in the book, but this one is more ambitious and, as you are doing it entirely for your own private interest, you should take your time over it and not let yourself feel rushed.

Considering these questions will almost certainly put you in a mood where other memories come flooding out. This mood of reverie may persist for hours or even days.

1 Write down or talk about your very favourite memory. With luck, you will have lots of good ones to choose from, and deciding which is the best will be part of the fun. Examining memories will also set off trains of thought that you will find interesting and rewarding.

2 Discuss, with yourself or others, who is the one person in your life you would like to meet again. Why is that person so important to you? Recall as many events associated with that person as you can. Once you start, you will find other memories begin to push forward into your consciousness.

3 List your greatest achievements. These need not be grand - you don’t have to have climbed Everest or explored the Amazon rainforest. Little things will do as long as they mean a lot to you.

4 Name a favourite TV programme from when you were a child. Remember as many details as you can. Just what was it you enjoyed so much? Would you still enjoy it now if you were able to see are-run?

5 Write something about pets you had in the past. Pet memories are often sweet and sad at the same time. They are also a very potent reminder of times past.

6 Discuss someone you knew who changed (or failed to change) the course of your life. What would you say to that person if you met him or her today?

7 Think of the five things you remember best about your parents. Parent memories are, of course, some of our most powerful. Handle with care!

8 What was the best job you ever had? And the worst? Did you follow the career you wanted? Have you enjoyed your working life or are there things you would have done differently?

9 What scene from your past would you most like to visit again? If you could, would you change anything or was it so perfect that you’d like to live it all over again?

10 Think of a day from the distant past in as much detail as you possibly can. Don’t just remember people and events, but conjure up memories of things, colours, textures and smells.

Be remembered