Emergency: This Book Will Save Your Life - Neil Strauss (2009)

Part V. RESCUE

Lesson 63

If any police officer ever gives you flak, get his name, then come to me.” Detective Mike Fesperman, head of the Devonshire police homicide division, was speaking in the roll-call room. It was my first time inside a police station. I always imagined I’d be entering in handcuffs, not as a potential reserve officer. “As far as I’m concerned, when you’re out there, you have the same status and respect as any police officer working the scene. I have tremendous respect for what your team does.”

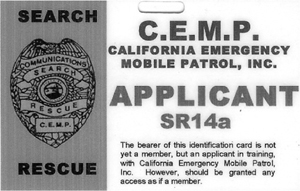

The team was the search-and-rescue unit I’d asked my EMT classmate about, California Emergency Mobile Patrol (or C.E.M.P.), a forty-six-year-old non-profit on call around the clock for the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles Fire Department. As instructed by the team’s applicant coordinator, I was wearing a white button-down shirt, black pants, and black boots. At the end of the meeting, I had to present my case to the group and then either be accepted or rejected as an applicant.

Fesperman was telling us about a body he’d found the previous week. It belonged to an artist who’d toured Europe with his work but lived as a vagrant in the park because he didn’t like confined spaces. A few days earlier, he’d bought beer for some teenagers. An argument ensued, he called one of their girlfriends a bitch, and the guys returned later and stabbed him.

It was one of the most violent stabbings Fesperman said he’d seen. To determine the date of death, a maggot was removed from the body and sent to the coroner’s office, where an insect expert pinpointed the murder time based on the life cycle of the larvae.

Fesperman wiped a hand across his brow. He was thin and bald, with taut skin and small, serious eyes that had seen the extremes of man’s inhumanity. He’d been a homicide detective for over a quarter century, as had his father.

If learning wilderness survival had thickened my skin, joining C.E.M.P. would certainly harden what lay beneath. Beyond the exposure to stress and violence, there were survival advantages I hadn’t anticipated: dozens of hours of rescue and police training; relationships with fire chiefs, police captains, and park rangers; field trips to the 911 call center, the coroner’s office, and the rest of the city’s emergency nerve center; police-blue uniforms, shiny metal badges, police radios, and cars with flashing lights and sirens that would get me past official roadblocks much better than my CERT uniform; and access to the government’s Wireless Priority Service program, which would give my cell phone precedence over other calls during an emergency when the network was tied up. Even Spencer couldn’t buy all that.

Three nights before, C.E.M.P. had helped Fesperman secure a crime scene. In this case, a fifteen-year-old girl had told her eighteen-year-old brother she’d found a rifle buried in the park. She led him to the spot and showed him where to dig for it.

But there was no gun. Unbeknownst to him, he was digging his own grave. When it was deep enough, his sister began stabbing him in the back. “What are you doing?” he cried out. “I’m your brother. I love you.” Suddenly she had a change of heart, stopped, and called 911. He was brought to the hospital in critical condition.

When asked why she’d done it, she simply told the police it was time for him to die.

“Human beings are animals,” Fesperman told us, scanning the room. “They’re vicious animals. Some of the things I’ve seen them do I could never even have imagined before I started this job.”

I thought my outlook on human nature was dark when I began learning survival. But the people I’d met along the way were far more Fliesian than I was—and they were in surprisingly good company. No less an authority on human nature than Sigmund Freud believed something similar. “I have found little that is ‘good’ about human beings on the whole,” Freud once confessed in an interview. “In my experience, most of them are trash, no matter whether they publicly subscribe to this or that ethical doctrine or none at all.”

Fesperman spent the next half-hour teaching newer members of the group how to preserve a murder scene. He told us not to touch the victims. Not to cover them with a blanket or sheet. Not to outline their bodies in chalk, despite what we’d seen in movies. Not to smoke, spit, or chew tobacco at the scene. And not to let anyone touch cigarette butts, bloodstains, or drag marks. All these things will contaminate DNA evidence and give the defense lawyer an opening to create doubt in the minds of jurors.

These rules, Fesperman continued, were especially important since, in a few months, the State of California planned to begin taking DNA samples from every person arrested within its borders.

I looked around the room after Fesperman said this, but no one else seemed disturbed. The official reason for inserting radio-frequency identification chips in passports and putting cameras on street corners and creating databases of people’s DNA, facial features, fingerprints, and irises is to aid investigators and to reduce crime and terrorism. But these measures come with an uncomfortable potential for abuse. At the press of a button, a government could turn these surveillance tools against its own citizens in ways that would make fascist regimes of the past seem permissive in comparison. Anonymity is a dying art.

“I look at every murder the same way,” Fesperman was concluding. “Whether it’s a celebrity or a vagrant, they’re still someone’s son or daughter.”

When the meeting ended, I was interviewed by the team about why I wanted to be a member and the skills I had. After I told them about everything I’d been learning and the hands-on disaster experience I was seeking, they went silent.

“Am I in?” I asked.

“We’ll let you know.”

Their words traveled into my ear, formed a lump in my throat, and stopped in a knot in my chest. I had no idea if I was the kind of person they were looking for. And I wanted, more than anything, to be part of the team. Not just for the experience, uniform, and siren. I wanted to belong.

Before entering the roll-call room of the Devonshire police station that day, I was alone and adrift in a world of panicked people. But in that room, there was a community of skilled men and women with a sense of purpose and mission. Unlike the paranoid PTs and the stockpiling survivalists, these were people who weren’t just trying to save their own lives. They had the resources, they understood the system, they knew the authorities, and they possessed not just the skills but the heart to help others survive in the cruel world Fesperman had described.

I walked to the police officer’s break room to await the team’s decision. Above the snack machines, World’s Wildest Police Videos flickered on a small television set.

A few minutes later, the applicant coordinator, SR77—no one here used names, only numbers—appeared in the doorway. “Welcome to the team,” she said. “I don’t know why they just didn’t tell you on the spot instead of making you suffer like that.”

I broke into a wide, relieved smile. Up until now, I’d sponged knowledge wherever I could find it. This was the first time I’d felt like part of something.

When I returned to the roll-call room, I was briefed on my responsibilities, a long list of team rules, and the minimum hours I was expected to put in every month. “In an emergency like an earthquake, your first priority is the safety of your family,” SR33, the team’s medical officer, sternly informed me. “When that’s taken care of, your next priority is the safety of your neighborhood. After that, your next priority is C.E.M.P.”

I didn’t realize it until that moment, but this wasn’t just a survival training decision. It was a life decision. As of that evening, I was no longer Neil to these people. I was an alphanumeric sequence. I was SR14a:

But rather than feeling like I’d lost my individuality, I felt like I’d gained a network.