Emergency: This Book Will Save Your Life - Neil Strauss (2009)

Part IV. SURVIVE

Lesson 34

I need to make two stops,” I told the cab driver. “First I have to go to Gun World on Magnolia. Then I’m going to the Burbank airport.”

As soon as the words left my mouth, I realized I sounded like a madman. I tried to think of some way to explain this sequence of stops rationally—that I wasn’t planning to spray gunfire in the airport but actually picking up a pistol so I could fly to a place called Gunsite in Arizona and learn to shoot. But that sounded just as dubious.

Though I didn’t think I’d be allowed to fly with a gun, when I called Southwest Airlines earlier that week I was surprised to discover it was fine, as long as I declared it and kept it unloaded in a locked case in my checked luggage.

The taxi driver, a bald, frowning Armenian in a sweat-stained white polo shirt, took me wordlessly to Gun World, checking me out in the rearview mirror every few minutes. Just in case he drove away, worried that I’d kill him or hold him hostage when I returned with my gun, I brought my suitcase into the store.

I’d first visited Gun World with Katie ten days earlier to buy a Springfield XD nine-millimeter, which Justin Gunn had recommended as a beginner’s pistol.

At the counter, a man with black hair, black glasses, a goatee, and a gun thrust down the back of his pants gave me an application that needed to be approved by the Justice Department. It asked typical security questions about whether I’d ever been in a mental institution or had any restraining orders against me. Oddly, it also asked, “Have you ever renounced your American citizenship?”

It seemed strange that this would disqualify someone from owning a gun, as if it were a sign of violent tendencies like a restraining order. Fortunately, it didn’t ask if I’d applied for any new citizenships lately. Even stranger, though providing my social security number was optional, the application required me to state my race. It seemed kind of, well, racist.

Next to me, two Polish guys in matching basketball jerseys were looking at .44 Magnums. They’d just turned twenty-one—the legal age for owning a handgun in California. One of them pointed the gun at the mirror, admired himself holding the weapon, then said, “Stick ’em up,” and mimed blowing away his victim.

Petrified by this pantomime, Katie asked the man at the counter, “Don’t you feel weird selling guns to people? I don’t think people should have guns.”

“It’s in the Constitution, you know.”

“They should just be totally illegal. I think only violent people would want to shoot guns.”

It was difficult to tell whether the clerk was amused or annoyed.

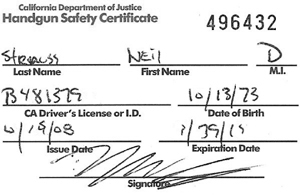

After I completed the Justice Department form, he explained that due to California state law, I’d have to wait ten days before I could pick up the gun. Then he slid me another piece of paper to fill out. It appeared to be some sort of test.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“You have to pass a handgun safety test first.”

I hadn’t taken a test in years. “Shouldn’t I study or something?”

By this point, it was clear that Katie and I were the stupidest people in the store. “Even if you were blind, you’d probably pass,” he said.

And he was right:

While packing for Gunsite ten days later, I dug through my closet to find practical clothing for shooting in the hot desert sun all day and under the cold desert sky at night. I came up nearly empty-handed. For most of my life, I’d bought clothes with the intention of being fashionable and hopefully attracting women. My jeans weren’t rugged and durable but slim-legged and waxy, and I wore accoutrements like wrist cuffs and wallet chains, which had no practical use to me—I didn’t even carry a wallet. I had the clothing of an urban café dweller, not a survivalist.

Katie tried to stop me as I left for Gunsite that morning. “I just don’t picture you holding a gun, babe.” She knew me well. “What if you get shot there? Or your gun blows up in your face?”

Those were the same questions I’d been asking myself. “I’ll be okay,” I said, as much to convince myself as her. “Why are you always so scared of everything, anyway?” I’d always wanted to ask her that.

“I think I watched too many movies as a kid. And I have a good memory, so I remembered all the scary things I saw. It’s a big world out there, and I’m a little person, you know.”

Though Katie was reluctant to admit it, movies weren’t the only source of her insecurities. Her stepfather used to punish her by making her kneel for an hour holding a box over her head and beat her if she dropped it. Once, on her birthday, he yelled at her for opening her presents carelessly, sent her to her room, and confiscated her gifts. And he constantly told Katie she’d grow up to be ugly, which is probably what led to her inability to leave the house without fixing herself up for an hour in the bathroom.

“When you grow up like that, you spend the rest of your life trying to avoid things that are dangerous,” Katie continued, “like dark alleys and cheerleading.”

“Why cheerleading?”

“I don’t want to end up on the top of the pyramid and fall off and break my bones,” she explained as I listened incredulously. “I don’t want to be on the bottom, because my back could break. And I don’t want to be in the middle, because someone could fall on me.” She paused and thought about it a little more. “There’s really no safe place in that pyramid, babe.”

“But what about bigger threats like terrorism and the economy?”

“I try not to think about those things.”

My fears, I realized, were different from Katie’s. Mine were forcing me out of my comfort zone; hers were making her retreat. And though it may be tempting to write off her fears as irrational, I later learned that roughly 66 percent of all severe sports-related injuries to female high school and college students are due to cheerleading accidents. And the main cause of those injuries is actually pyramids.

Nonetheless, I needed to find a way to make Katie face her anxieties, because they were holding her back from life and making her too dependent on others to take care of her. Before I could help her with her fears, though, I needed to do something about my own.

After picking up my gun, I resumed my taxi ride to the airport with the nervous Armenian driver.

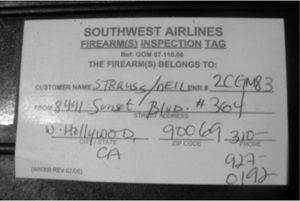

Fifteen minutes later, with my heart in my throat, prepared at any moment for security to wrestle me to the ground, I walked to the airline counter and repeated the exact words the clerk at Gun World had told me to say: “I’ll be checking in a firearm. It’s in my duffel, and it’s in a locked case and unloaded.”

“I’ll need to see it,” said the ticket agent, a pasty blond woman dotted with moles. She eyed me suspiciously. Maybe I was too nervous.

I repositioned my body in an attempt to block the view of the passengers in line behind me, and removed the case from my duffel. Then I placed it on the scale, unlocked it, and pulled this out:

Nobody panicked, nobody screamed, nobody tackled me. At that moment, if I’d wanted, I could have sprayed bullets all over the airport. But that would have made me an idiot, and the point of the gun was to protect myself from idiots like myself.

After telling me to remove the magazine, the mole lady asked me to put the gun back in the case and then taped this label to it:

“As a precaution,” she added after giving me a boarding pass, “you may want to wait near that door for ten minutes in case TSA has any questions.”

When no one appeared after fifteen minutes, I headed through security and to the gate, on my way to Arizona to learn how to kill.

Although a gun can’t do much harm in a locked box in a plane’s cargo hold, I had no idea it was this easy to fly with a firearm. It was the first time since I began this journey that I discovered a freedom I didn’t know I had, rather than a new restriction.