Emergency: This Book Will Save Your Life - Neil Strauss (2009)

Part III. ESCAPE

Lesson 27

When I took a cab to the island’s capital, Basseterre, at five A.M. the day after Christmas, the J’ouvert street party—the climax of the island’s two-week-long carnival celebration—was in full swing. Bands lined the sides of floats and trucks, hammering away on steel drums as hundreds of drunk revelers danced ecstatically behind them. It was not a show for tourists, but an age-old rite occurring despite my presence. It seemed hypocritical to call this place my home when these were not my people and this was not in my blood.

I didn’t belong here. Kevin didn’t belong here. Victor didn’t belong here. Regan didn’t belong here. The Russians, Ugandans, and all the eccentric real-estate developers with their big dreams didn’t belong here.

Then again, there was a time when these revelers didn’t belong here either. The Kalinago tribe fought the Igneri tribe for the island. The French and the Spanish fought first the Kalinago, then each other. The French and the British then fought, uniting briefly to massacre nearly the entire native population at a site now known as Bloody Point.

Yet still the island belongs to no one. It’s just a neutral witness to human nature. And all that blood—like most of the blood spilled over man’s inability to cohabitate and share—has been shed for nothing. So until the battle resumes one day, the island’s guests will spend their time exchanging pieces of paper that represent value for other pieces of paper that represent land, just as we do everywhere else in the world. More than warfare, this symbolic paper, a single sheet of which can make a man a slave or a king, is the pinnacle of human civilization.

And that afternoon, I had my final meeting with a member of the race of man dedicated to the mastery of that paper: my lawyer.

“I can deal with bastards, but I hate assholes,” Maxwell was telling someone on the phone when I entered. “Some people, they shouldn’t be dealt with nicely.”

When he hung up, I tried to make small talk and asked how his holiday had been so far. This was a mistake.

“I’ve been working the whole time. I can’t take a vacation like you.” He seemed to feel he was the only person in the world who had to work. “It’s because of this thing.” He pointed to the mobile phone hanging from his belt. “It never stops.”

I pulled the forms he’d given me out of an envelope I was carrying. I’d filled in my name, address, and my parents’ address. But other questions—asking for my occupation, annual income, and reason for wanting the citizenship—I’d left blank, because I had no idea what the government was looking for. If it wanted to attract rich investors to the island, it would probably reject me because I was just a writer and my income was nothing in comparison with the business magnates and Russian mobsters who usually applied for citizenship. So I asked Maxwell for advice.

“Is it better to put writer or author?”

“Doesn’t matter.”

“How should I describe my source of income?”

“They just need a guarantee that you have an income.”

“Okay. One last question, then I’m out of your hair: what should I put down where it asks ‘reason seeking citizenship’?”

He groaned as if he’d rather be in Guantánamo getting tortured and uttered with great effort, “‘Alternative citizenship and future retirement home.’”

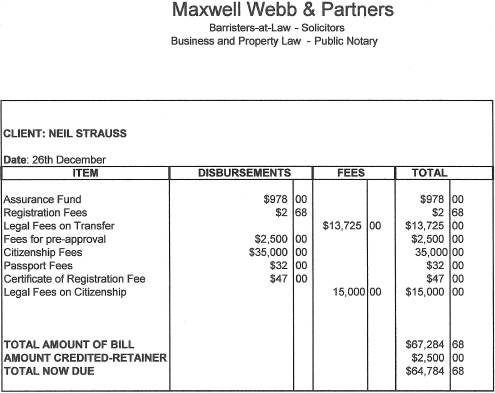

As I filled out the rest of the application, he yelled something about making a mistake on my invoice at a beleaguered secretary, who was wearing inordinately high red peep-toe shoes. She returned a few moments later with the largest bill I’d ever been handed in my life:

I didn’t have that kind of money lying around.

“I’ll need you to wire that to my account,” Maxwell informed me, “along with the full cost of the apartment.”

“I thought I was just supposed to pay a ten percent deposit.” Cold sweat began prickling my forehead and the back of my neck.

“The government likes to see all the money in an account so they know you won’t back out.”

Until that moment, I hadn’t given much thought to the practicalities of affording the citizenship. Perhaps if I took out a second mortgage on my current home, I might be able to raise that amount. Then I could take care of the monthly mortgage payments by renting out the unit when I wasn’t on the island. So not only would I become a citizen of St. Kitts, I’d also become a foreign real-estate speculator and shady landlord.

But it was still a devastating amount of money. What if I was a victim in some sort of long con? Maxwell had the home-team advantage. I was completely at the mercy of his word.

He irritably shuffled through my documents and handed me a piece of paper that would, hopefully, become my passport one day. “Write your name inside the box, but make sure it doesn’t go outside the box,” he told me, then repeated it, as if I were stupid.

“In order to submit your application,” he continued, “I’ll also need a negative HIV test, a clean police record, nine passport photos, and a copy of your birth certificate.”

I handed him the lease agreement for St. Christopher Club and asked him if it was okay to sign.

“I did all the documentation for St. Christopher Club,” he replied, as if offended I’d dare to ask such a question.

“So you wrote this agreement, then?”

A vertical tremor in his face seemed to imply his assent. This was quite possibly the stupidest thing I’d done in my life.

“So,” I asked, hoping for more reassurance than at my last visit, “what’s the likelihood of this going through?”

“As long as you have no criminal record, a clean HIV test, and no tax problems in the U.S., you’re fine,” he replied.

“Anything else ever go wrong?”

“As long as you have no criminal record, a clean HIV test, and no tax problems in the U.S., you’re fine.”

It was clear he just wanted me out of his office. Foolishly, I tried to make more small talk in an effort to befriend him. “Hope you get some free time in.”

“I have another client coming,” he responded. “Can I ask you to leave?”

I walked out with a sinking feeling in my chest.

In the Andrei Tarkovsky film Stalker, just before making a fateful decision, one character says to another, “There must be a principle: never do anything that can’t be undone.”

That principle is why, on the brink of a big decision, the first thing to fill my mind is doubt. What separates the strong from the weak, I reminded myself as I wandered sticker-shocked through the streets of Basseterre, is the ability to act instead of spending most of life paralyzed, too scared to make a choice that might be wrong.

St. Slim Jim, patron saint of reckless decisions.