The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language - John McWhorter (2014)

Chapter 4. Dissing the Chinese

MUCH OF THE APPEAL of Whorfianism is the idea that other people’s languages lead them to pay more attention to certain things than English speakers do. Investigators seek to show that certain particularities of a language make people more sensitive to the material of things, to grades of blueness, to the gender that their language happens to assign to inanimate objects. Indeed, many languages are chock full of constructions that call attention to nuances of environment that an English speaker would scarcely imagine any language’s grammar would have anything to do with. One duly supposes that all of the bells and whistles in such a language might indicate a kind of hypersensitivity to certain facets of living—that the rest of us ought marvel at and perhaps even take a page from.

The Normal Language: Beyond English Indeed

Part of what got thinkers like Whorf and other specialists in Native American languages into this frame of mind is that those languages tend to be janglingly elaborate in terms of what they pay attention to. The impression from a Native American language is typically that there is so much of it—that is, that one must attend to so very many things just to form a basic sentence. Of the languages in the world so full of meticulously particular distinctions that I can’t quite wrap my head around the idea of someone speaking them without effort, outside of the Slavic languages, almost all of them are Native American ones. Sitting in on a seminar at Berkeley about Cree years ago, for example, I endlessly remarked to the professor Richard Rhodes that I could not believe anybody could keep track of so many things in a language they actually lived life in—and he knew what I meant and cherished the language for exactly that reason. (It is to him that I owe a great deal for calling attention to the fearsome complexity of indigenous languages.)

The Atsugewi language of California is a great example, extinct as of recently but while it was still spoken, goodness gracious! For example: the sentence for “The soot flowed into the creek” was W’oqhputíc’ta cə ni?ə qáph cəc’uméyi. Breaking it down into its pieces in all of its forbidding unfamiliarity need not detain us here; suffice it to know that within that one sentence is a magnificent fussiness.

The word for move is a specific one used when referring to things like dirt—if it’s other things moving you use different words for move. The word for into is used only if it’s liquid being gone “into”; otherwise you use other words for into according to the substance (shades of that New Guinea language Yélî Dnye’s multiple words for on). Never mind that there’s already a suffix elsewhere in the sentence that itself means just “to”—it’s as if the language somehow thinks that wouldn’t be enough. Another suffix tells us that the sentence is factual as opposed to hypothetical, which would seem to be obvious from the fact that the person is saying it, but this language dots its i’s and crosses its t’s indeed! Then, the cə (pronounced roughly “tsuh”) marks the words soot and creek as nouns—just in case it isn’t clear that they are.

There is something delicious in speculating how a language like that might shape the thoughts of its speakers—lots of different words for move, into-ness being a Hydra-headed thing, getting highly explicit that things are things. To the extent that it might even give an English speaker a touch of an inferiority complex about our less elaborate language, this, too, can feel welcome in its way. Seeing how languages like Atsugewi work is an elegant and conclusive lesson in the mental equality of all human beings.

Whorfianism, here, seems beneficial.

But.

![]()

Languages differ much more than Atsugewi and English in how much they pack into a sentence. English, as languages go, is about in the middle of a scale of telegraphicness. It’s easy to suppose that English’s degree of complexity is “normal,” but a great many languages make English look like Atsugewi.

Let’s take a simple and endlessly translated sentence: In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. In languages that scan the way we are accustomed, that sentence requires attending to certain grammatical processes. In English, the sentence marks the past tense (created), has definite articles, and marks the plural (heavens). In the original Hebrew, this was Bereshit bara Elohim et hashamayim ve’et ha’arets. This, too, had past tense marking in bara“created,” definite articles (ha-), and plural marking (-im), as well as marking the heavens and the earth as objects rather than subjects with the et particle.

Other languages pack a little more into the sentence. In Russian, it is B načale sotvoril Bog nebo i zemlju. There is no definite article in Russian, but we have the past tense, the plural marking, and the marking of earth (zemlj-u) as an object with a suffix. In addition, Russian requires that we mark “beginning” with the locative marker -e (načal-e), and the so- in the word sotvoril for “created” serves to indicate that the creation happened at one time rather than over a long period.

Other languages utterly unrelated to European or Middle Eastern ones operate on quite a different plan, but maintain about the same level of busyness. In Tagalog, the main language of the Philippines, the sentence is Nang pasimula ay nilikha ng Diyos ang langit at ang lupa. The little word ay just pops up when you start a sentence with something other than a verb. Never mind why, but it’s something you have to do—grammar. The ni- part of nilikha “created” is another one of those persnickety markers that something is real rather than made up. Then Tagalog has articles of a sort: the difference between the ang’s and ng’s is rather similar to that between the and a.

Yet a language can “care” about much less than these do. In Mandarin Chinese, In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth is Qĭ chū shén chuàng zào tiān dì. Those words mean simply “start start God achieve make sky earth.”

There are no endings of any kind. There is no marking of the past, no definite articles, and no plural marking. There is no marking of anything as an object, much less marking the “beginning” as located “at” a place. The Chinese speaker neither reminds their interlocutor that what they are saying is “actual” nor even has to link the words for the sky and the earth with a word for and! Start start God achieve make sky earth.

This is Chinese. For a Westerner, much of mastering the language is a matter of getting used to how very much does not have to be said. Yet it leads to a question. If languages that are bubbling over with fine-grained distinctions about materials and the definiteness or actuality of things are windows into the minds of their speakers, then what are we to suppose Chinese’s grammar tells us about the minds of its speakers?

More generally, if it is true that what’s in a language’s grammar reveals to us what its speakers think about most readily, then what does a language suggest about its speakers when its grammar requires attention to relatively little? If Atsugewi represents a worldview, then it would seem that the worldview of the Chinese is rather uncomprehending and barren.

Whorf, in a less-often quoted passage, seems to have anticipated that his framework required some kind of address of the variable complexity among languages, venturing that “it may turn out that the simpler a language becomes overtly, the more it becomes dependent upon cryptotypes and other covert formations, the more it conceals unconscious presuppositions, and the more its lexations become variable and indefinable.”

One senses that Whorf thought of these “covert formations,” “unconscious presuppositions,” and endlessly “indefinable” meanings as potentially weighty stuff. However, it is hard to imagine what scientific approach could illuminate such obscurity and murkiness. The whole idea is close to saying that English speakers have thoughts while Chinese speakers merely have notions.

Whorfianism, here, seems dangerous.

A Blooming Mess

And that has hardly been a renegade sentiment where Chinese is concerned. After all, the nature of Chinese grammar is such that one might venture that speaking Chinese makes one see the world not just differently, but dimly. There has been academic speculation along exactly those lines, and predictably, the wonder and romance that traditionally greets Whorfianism fell instantly away. The question is what this means for the whole enterprise.

The case in question is that of psychologist Alfred Bloom, in the early eighties. Bloom did nothing but follow in the footsteps of what was even by then decades of Whorfian work, and investigated whether how Chinese works affects how Chinese people think. However, this time, his focus was not on multiple words for colors or bouquets of words indexing what things are made of, but an absence of something.

Namely, a language like English is highly particular in encoding hypotheticality. To an English speaker, it seems as normal as the law of gravity that there are three similar but different sentences such as:

If you see my sister, you’ll know she is pregnant.

If you saw my sister, you’d know she was pregnant.

If you had seen my sister, you’d have known she was pregnant.

The three connote different shades of nonreality; the first (If you see my sister …) implies that something will likely happen. The second (If you saw my sister …) makes the business an imagined scenario. The third (If you had seen my sister …) shifts the entire matter, complete with its hypotheticality, into the past.

In Mandarin Chinese, only with a studious elaboration unnecessary to casual speech could one convey those differences. All three sentences would be rendered as “If you see my sister, you know she is pregnant,” without the specific marking of pastness and the conditional (you’d, i.e., you would) that English uses as a matter of course.

Here, then, is another example of how in Chinese, in the relative sense, one simply doesn’t have to say much. Word for word the rendition is roughly “If you see I sister you know she pregnant get” for all three of the English sentences. So: if separate words for dark blue and light blue mean Russians perceive shades of blue “more” or “faster” than we do, and if an array of words marking what things are made of means that the Japanese process material “more” or “faster” than we do, then certainly if Chinese marks the hypothetical less explicitly than English, then the Chinese process hypotheticality “less” or “more slowly” than …

You can likely imagine the response.

It wasn’t a witch hunt, but it elicited a suspiciously long trail of reply articles compared to cozier Whorfian work, especially for a book published long before the Internet era. There have been five major anti-Bloom pieces, trucking all the way up to 2005, a quarter century after Bloom’s book appeared, by which time he had long ago moved on intellectually and occupationally. One also gleans, in the reception, a certain visceral component between the lines. All of the responses are thoroughly professional and civil, but the title of one is “A Response to Alfred Bloom”—why so personal? More typical would be “A Response to Bloom (1981)” or no mention of his name at all. Or, the subtitle of another one is “Picking Up the Pieces”—what broke? There would seem to have been what some processed as a bit of a brawl.

Frankly, there would almost certainly have been one if Bloom published his work in our era. Talk about your hypothetical—if Bloom ventured that Chinese makes its speakers less attuned to the difference between the real and the imagined today, then today he would be roasted in the blogosphere for months. It’s not an accident that Peter Gordon’s and Dan Everett’s claims about the Pirahã have elicited an analogous volume of academic resistance, as Whorfian work highlighting deficit rather than advantage.

Yet Bloom did not just toss out his speculation without demonstration. He presented Chinese and American subjects with a story that could be interpreted counterfactually or concretely. Seven percent of the Chinese speakers chose the counterfactual interpretation, while 98 percent of the Americans did. He also posed to Chinese speakers perfectly plausible questions such as “If all circles were large and this small triangle were a circle, would it be large?” He found that far too often for it to be accidental, his subjects answered along the lines of “No! How can a circle be a triangle? How can this small circle be large? What do you mean?” English speakers had this response much, much less often.

Bloom, in exactly the same tradition of thought that people have found so attractive when applied to heightened sensibilities among Native Americans, concluded that speaking a language leaving much hypotheticality to context leaves a person’s thought patterns less attuned to it than an English speaker’s.

Over the years, researchers responding to Bloom have gotten different results from his. Their interpretations as to why involve how degrees of experience with English affect Chinese people’s responses to such questions, how felicitous Bloom’s translations into Chinese were, and Chinese people’s possibly being better at grappling with hypotheticality applied to ordinary situations rather than deliberately abstract ones. Yet, Bloom of course offered responses to the responses.

At the end of the day, the observer’s verdict is that Bloom was on to something, but not in a way that Whorf would have found especially compelling. There were hints of the truth even in the responses Bloom got at the outset, when subjects tended to object to the peculiar “what if” questions as “unnatural,” “un-Chinese,” “confusing,” and “Western.” Bloom’s approach was to guess that these responses were surface manifestations of something driven ultimately by language affecting thought. However, just as plausible is that these thoughts represented, well, thought.

More specifically, could it not be that there is something in being Chinese, not speaking Chinese, that occasions a less ready engagement with useless brain-teaser questions like the ones about triangles being, just for the sake of argument, circles?

Evidence for that argument would be if speakers of a language as rich in markers of hypotheticality as English were as uncomfortable pretending triangles are circles as the Chinese subjects were. That evidence exists.

Linguist Donna Lardiere has shown that Arabic speakers sound quite “Chinese” when presented with what are, ultimately, silly questions. Arabic is not a telegraphic language in the slightest. It has explicit grammatical machinery to, if necessary, situate hypotheticality in the past to yield pluperfect if I had and conditional would-style meanings if necessary, such that “If you see I sister you know she pregnant get” seems just as queerly elementary to an Arabic speaker as it does to an English speaker. Yet Lardiere found that when presented with questions like the triangle bit, Arabs typically had responses such as: When you learn something you learn as it is—a circle is a circle, get what I mean? And a triangle could never be a circle.… If I agreed with this, it means I’m disagreeing with everything I did in math, it’s like, how could an orange be an apple? Well, I don’t think it’s possible.

It would seem that we are dealing indeed with a difference in mindsets, but conditioned by culture rather than language. The main lesson is actually that the very familiarity a reader of this book is likely to have with counterfactual questions like the one about circles and triangles is a cultural trait rather than a human universal. As Lardiere notes, it is hardly just Chinese and Arab people who are often thrown by direct questions unconnected to utilitarian context. Studies such as linguistic anthropologist Shirley Brice Heath’s classic Ways with Words demonstrate that direct and out-of-context questions themselves, along the lines of “What is the capital of South Dakota?,” are an artifice of educational procedure much less natural in oral cultures in general, in which the direct question is often processed even as abrupt and confrontational. This possibly explains differentials in educational success between middle-class and less fortunate children (of all races) in the United States.

Equally pertinent is fascinating work in the 1930s by A. R. Luria in what is now Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan with illiterate or near-illiterate peasants. For example, Luria asked subjects “in the far north, where there is snow, all bears are white. Novaya Zembla is in the far north and there is always snow there. What color are the bears?” Responses ranged along the lines of “I don’t know. I’ve seen a black bear. I’ve never seen any others … each locality has its own animals.” Sound familiar? Respondents tended to find the very idea of answering questions disconnected from real-world utility idle, boring, and even faintly ridiculous.

There are endless directions to go in from the fact that human cultures and subcultures differ in their openness to engagement with questions that are abstract for their own sake. However, the evidence for this mindset being created by an absence of particular words or constructions that translate as, say, I would have been or I had been has not held up. And on Chinese in particular, we might question whether we would have wanted it to, because it would signal something much larger.

Namely, if no way to indicate I would have been or I had been in your language leaves you slow to wrap your head around the hypothetical, then imagine what we would be faced with in Chinese’s lack of so very much else. Chinese has no definite articles. It has no marking of past and future—no I walked or I will walk; tense is often just left to context and they do just fine. It has no difference between he, she, and it, or evidential markers, and forget about any subjunctive. It does not even usually mark things as plural. Chinese, overall, takes it light. Really light.

And let’s imagine: one careful article after another about all of these grammatical nonfeatures could possibly make a case about Chinese “shaping thought” in rendering its speakers infinitesimally less sensitive to such nuances of living. And the result would be a loomingly miserable proposition, which, no matter how artfully phrased, would constitute a grisly case that to be Chinese is to be not especially quick on the uptake.

Condemnation would be swift and indignant, and it is here that it becomes urgent to reconsider that the psychological differences revealed in even the finer Whorfian experiments are so small. When the results can potentially be framed as meaning that some people perceive time as vertical, or process differentials of blueness as “popping” enough to contort their take on paintings from Picasso’s blue period, many will seek ways of reading those small differences as having some kind of larger import. However, as it happens, the controversy over Bloom’s work actually leaves hints of the same kind of small but present result, suggesting some shade of influence from language upon thought.

Bloom, in one wing of his project, found that Chinese-English bilinguals performed better than Chinese monolinguals, concluding that commanding English affords a person a connection with hypotheticality that someone speaking only Chinese lacks. Also, L. G. Liu and then David Yeh and Dedre Gentner have shown that Chinese speakers perceive counterfactuality more readily when presented with familiar situations rather than abstract ones—upon which the fact remains that English speakers display that differential much less. That is, there may be something about English and hearkening to the difference between the real and the possible.

Here, however, where we are faced with the Chinese possibly exhibiting a handicap, note how much less savory it seems to magnify squeaky differentials laboriously glimpsed under artificial conditions into a statement about a people and how they wield their cognition amid this thing called life.

Choosing Which Differences Matter

Plural marking in Chinese as compared to other languages helps illuminate the heart of the issue.

Chinese doesn’t care much about how many things there are. Things are marked for plural only for explicitness and more when they are alive; otherwise, for the most part plurality is left to context and no one bats an eye. It’s European languages, among others, that are oddly strict about indicating overtly whenever there is more than one of something. Notice that the previous sentence would have been thoroughly processible if one could say, “It’s European language that is oddly strict.…”

Take Genesis again: English has “And God said, ‘Let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth.’” Chinese has “God say water force much much multiply have life life of matter, and have sparrow bird fly at ground above” (Shén shuō shuĭ yāo duō duō zī shēng yŏu shēng mìng de wù, yāo yŏu qiāo què niăo fēi zài dì miān yĭ shàng). Chinese shows us that plural marking, seemingly so normal, is actually, as languages go, a tic, an obsessive-compulsive disorder that a language might wend its way into. Atsugewi means you just have to specify what kind of moving, and into what, and don’t forget to always show that a noun is what it is, a noun. In the same way, English is a contract under which you agree to always specify overtly that there was more than one of something. Something bubbles up somewhere in any language.

Yet it is hardly inconceivable that a Whorfian experiment could be devised that showed that Chinese speakers, in some way, to some extent, are—quite slightly—less vividly attuned to how many of something there is when presented with, say, two rather than one objects on a screen. Why not, after all? In the introduction I noted that Whorfianism has been problematic in tending to only examine a few languages at a time, but Whorfianism has also only examined a highly constrained set of grammatical features. If language shapes thought, then what decides which aspects of it do so? Why not how a language encodes the plural?

Or doesn’t? On Chinese’s wan commitment to marking plurality, a Whorfian take would presumably have to be that as elsewhere, “language shapes thought.” Yet most of us would wonder whether we were really to process Chinese people as significantly less attuned to there being two cups that need washing rather than just one, that two buses went by instead of one, and that there are two people in the living room rather than just one. Or: if Chinese people do process twoness a nano-peep less alertly than English speakers, is it to an extent that anyone could reasonably consider a different way of processing existence?

We gain perspective on the notion in viewing it from the other extreme. Suppose a language could be analyzed as making its speakers even more attuned to plurality than English? Suppose a language were one of the ones, say, of a breed in Africa Westerners are rarely aware of, such as the one spoken by the tragically burdened people of Darfur?

In their language, called Fur (Darfur means “the land of the Fur”), plurality is basically irregular, period. In English you mark the plural with -s except for a dozen or so strange cases like children, mice, geese, and men. But imagine a language where almost all plurals were like that! That’s Fur. Thief: kaam. Thieves: kaama. But eye: nuunga, eyes—kuungi. You think child/children is odd? Try Fur: child, kwe. Children, though, is dogala! And that’s how it is for all nouns—you just have to know.

In a language related to Fur, Sudan’s Dinka, fire is biñ while fires is biiiñ where you make the i in the middle three times as long (yes, you really do!). Palm fruit is tuuk said on a low tone; say it on a high tone and you get palm fruits. Man: mooc. Men: Rooor! Women roar too—woman: tiik; women: djaaar! But hippos don’t: one of them is a roow, two of them are root, and you just have to know, just like you have to know that one blade of grass is a nooonwhile if there are more, they have one less o and are noon, and on and on, with every noun.

There is barely anywhere to grab on. And it could be taken as meat for a Whorfian analysis. Remember: if Russian has separate words for dark blue and light blue, then that means Russians perceive shades of blueness meaningfully more vividly than English speakers. Okay: but it follows that we might ask a like question. If Fur and Dinka speakers have randomly different words for two of something rather than one of something, then presumably that means that Fur and Dinka speakers perceive shades of plurality more vividly than English speakers. If the Russians have their blues, then the Fur have their eyes—nuunga and kuungi—different “eyes” on the world, right?

And just suppose an experiment showed speakers of these languages hitting a button just a whisper faster than someone from New Haven when they saw a picture on a screen switch from depicting one house to depicting two. Or, presented with a big square with two dots in it, hitting the button faster when the screen added underneath a picture of two cows rather than one.

I lack the cleverness of the top-class Neo-Whorfians; they could devise an apter experiment. But I seek a larger point. Many are receptive to the idea of Russians with their blues, or Europeans and their tables talking with high voices—that’s from a study that showed that speakers of languages that assign gender to inanimate objects are statistically more likely to imagine them with traits corresponding to the “sex” they belong to. But fewer would cotton to the idea that in real life, in a fashion that the humanist or an interested NPR-listening layman ought heed, certain African tribespeople process the difference between one dog and two more immediately than those reading this book.

One assumes that whatever a psychological experiment might eke out of a person in an artificial context, whatever eensy-weensy differences on that score one might find in the cosseted context of a psychological experiment, all human beings are in the same mental boat on one versus two, in terms of what could impact anything we know as this life we are all living, how we deal with it, and what we create on its basis.

What’s cool about Dinka is that all the plurals are irregular. All languages are, in their own ways, as utterly awesome as creatures, snowflakes, Haydn string quartets, or what The Magnificent Ambersons would have been like if Orson Welles had been allowed to do the final edit. What’s cool about Dinka is not, however, that it makes its speakers quirkily alert to there being more than one of something.

![]()

The question is why that same verdict doesn’t apply to the Russian blues, the Japanese and their materials, or even that other trait Whorfianism has applied to the Chinese, their supposedly vertical sense of time. The Whorfian objects: “Of course all people process plural versus singular—but we’re on to things like vision and sensation and time.” Yet I am aware of no analysis spelling out just why vision and time are more pertinent to cognition than something as basic to experience as number. No matter what clever studies showed about differentials within milliseconds of response, no researcher would gain any traction from claiming that a goatherder in central Africa is more alive than an accountant in Minneapolis or a shoemaker outside of Beijing to there being two people in front of him than one. Why, then, would differentials in milliseconds about anything else in a language shed significant light on something as portentous as How People See the World?

Whatever the responses might be, they would have to square with the fact that there are countless languages in the world that present the speaker of a European language not with more—dark blue and light blue—but less. Some of them don’t even have a word for less. In the rain forest of Surinam in South America, descendants of slaves who escaped plantations in the country in the 1600s live today in thriving communities, speaking their own language called Saramaccan. It’s a blend of words and grammar from English, Portuguese, Dutch, and two African languages, and is not a variety of any of them, but very much a language of its own.

As a real language, it has its quirks. One of them is that to say She is less naughty than him, you must say He is more naughty than her; there simply is no word corresponding to less. There are many languages that have no word for less of this kind; if you think about it, it doesn’t matter—as long as there is a way to say more, less is, technically, a frill. You can always express a thought via mentioning the element that is more rather than the one that is, consequently, less.

Does this mean that Saramaccans, living life as vividly as we do, are less attuned to differences in degree than other people? And more to the point, note how unlikely it is that anyone would attempt to find out, despite Whorfianism’s supposed purely intellectual interest in whether language shapes thought. In comparing other languages with English, the Whorfian quest is fonder of the mores than of the lesses, as it were.

This, however, makes hundreds of languages of East and Southeast Asia risky business for Whorfianism, as they pattern much like Chinese. If the Laotian in his language says Aren’t you afraid the boss will be disgusted when you are preparing food?, he expresses it as “You not fear boss crap-disgust right?, you make eat?” No tense, no articles, no -ing, no when conjunction. If language affects thought, then what kind of thought are we to attribute to the population of Laos? Or Thailand, given that Thai and Laotian are essentially the same language?

Here, there is a possible objection. Of course, there are things in a language for a Whorfian to investigate beyond how much or little it marks overtly. We have even seen this with Chinese, in studies of whether its speakers process time vertically: this refers not to how detailed Chinese’s marking of time is or is not, but simply in what kind of words it happens to use for the purpose. However, this leaves my question in this chapter standing and just as urgent.

Here’s why. All languages differ from other ones in countless random ways analogous to English’s next month being the month below in Chinese. For instance, just for this expression it’s the month that comes in Spanish, the following month in Russian, front month in Indonesian, and so forth. Yet besides this kind of six-of-one/a-half-dozen-of-the-other differentiation between all languages, Chinese remains distinct from so very many of them in a particular way: its laconic essence compared to European and most other languages.

That quality stands eternally alongside the month below kind of things, and as Alfred Bloom saw, would seem to be as subject to Whorfian questions about how language shapes thought as anything else. Yet, for example, the Bloom study is not even mentioned in Deutscher’s Through the Language Glass. As honest as that book is about how Whorfianism has fared, perhaps the Bloom story seems too utterly awkward to allow any room for languages as different pairs of glasses.

The take-home message is that language varies awesomely despite a single basic human cognition. The take-home message is not, however, that how languages vary teaches us about how cognitions vary. Tempting as the latter analysis may be, it will eternally run up against things such as that across Indonesia, the way to render Someone is eating the chicken in casual speech can be just Chicken eat! Anyone who has spent time in Indonesia will readily attest that the nation’s people are vastly more reflective than anything a sentence like that—typical of much colloquial Indonesian—suggests about language shaping their thoughts. Where is the warmly received Whorfian literature about how certain languages might make their speakers less aware of something central to existence? My goal in this book is to show that the essence of language absolves us from having to even treat that as a problem.

And a problem it is. Take the possible riposte that I am caricaturing Whorfian work, when it only suggests that a language makes its speakers only somewhat more likely to think in certain ways. Just somewhat. That riposte is well and good when applied to how vividly someone might perceive gradations of blue, or even how vertically someone might perceive time going by. But that riposte also boxes one into agreeing that the telegraphic nature of Chinese suggests that its speakers are somewhat dumb. Let’s not caricature—just somewhat. But still. If you want the grits you have to take the gravy.

To wit, if when faced with Chinese’s telegraphic quality the proper response is to suppose that any cognitive consequences are too minimal to be treated as affecting thought and culture, then one must ask why the verdict is not the same even when the data happen to suggest greater, rather than lesser, alertness to some aspect of being human.

Whorfianism and Thrift

Might there be a way to mine Whorfian gold from the terseness of Chinese nevertheless? It’s been tried, in a pleasantly oddball fashion. I always suspected someone would try it, as there is a precedent for its approach in a passing idea some linguists venture on a related topic.

A truism in the academic linguistics realm is that all languages are equally complex. The truism is well intentioned and even benevolent, in that it stems from a quest to demonstrate that languages of “undeveloped” groups are not jibberish. Linguist/anthropologists of the early twentieth century of the kind who influenced Whorf, such as Edward Sapir and Franz Boas, set this discovery in stone, showing that Native American languages like Navajo are, if anything, more complex than French and German.

They are—boy, are they! However, the fundamentally advocational and defensive stance here—itself invaluable—settled into a general recoil from the idea that any language could be less complex than any other one. That sense reigns still among linguists, anthropologists, and fellow travelers. Yet it is impossible not to notice that when it comes to complexity, languages do differ.

No one who knows English and Chinese could miss what we have seen in this chapter, that overall, you simply have to say less in a typical Chinese sentence than in an English one. However, what’s less known to most is that compared to possibly most of the world’s languages, English is rather like Chinese. For example, in languages like the one used on Rossel Island off of Papua New Guinea that I mention in chapter 2, in the typical sentence you have to pack in things an English speaker would never dream of having to actually attend to, such as endlessly fine shades of what it is to be on something, or even using assorted suffixes to indicate whether the he or she you mention is the person you were just talking about or some new he or she, or even other suffixes to show whether you are doing something (like walking) or just undergoing something (like falling). Some languages are just much busier than others.

In response to this, knowing that some languages also attend to much less of the nuance of reality than that—for example, Chinese—some linguists fashion a way of maintaining the idea that all languages are equally complex: the idea that having to glean something from context is, in itself, a kind of complexity. Under this analysis, there are two kinds of complexity. It’s complexity that English has to mark something as happening in the past with -ed or to carefully index grades of hypotheticality with the if’s and then’s and conditional mood and such. But then it’s also complexity that in Chinese you have to glean those kinds of things from context. That is, reliance on context is, itself, complex.

Well, okay. I find the idea forced, and no one has ever demonstrated it scientifically. However, it’s always out there, and it means that it’s only a matter of time before someone proposes that in Chinese, since absence is complexity too, not having a grammatical trait can force attention to something just as having it can.

That is exactly what Yale economist Keith Chen has put forward about Chinese and other languages. His thesis is peculiar and bold. Chinese does not have a future tense marker along the lines of English’s will. Many languages don’t and leave future largely to context. Chen proposes that in countries with languages that don’t mark the future regularly, like China, the absence of the future marking makes people pay more attention to futurity—and makes them more likely to save money! And pay more attention to preventative health practices and such. To be clear: the idea isn’t that having a future marker makes you pay more attention to the future, rather, not having one does.

Needless to say, the media loved this, especially with Chen providing the deeply quantified kind of analysis economists are trained in. Might it be that quietly, how people’s grammars work has actually had an impact on their countries’ economies? As weird as that seems, might it be that the truth, however bizarre the notion seems, is in the numbers?

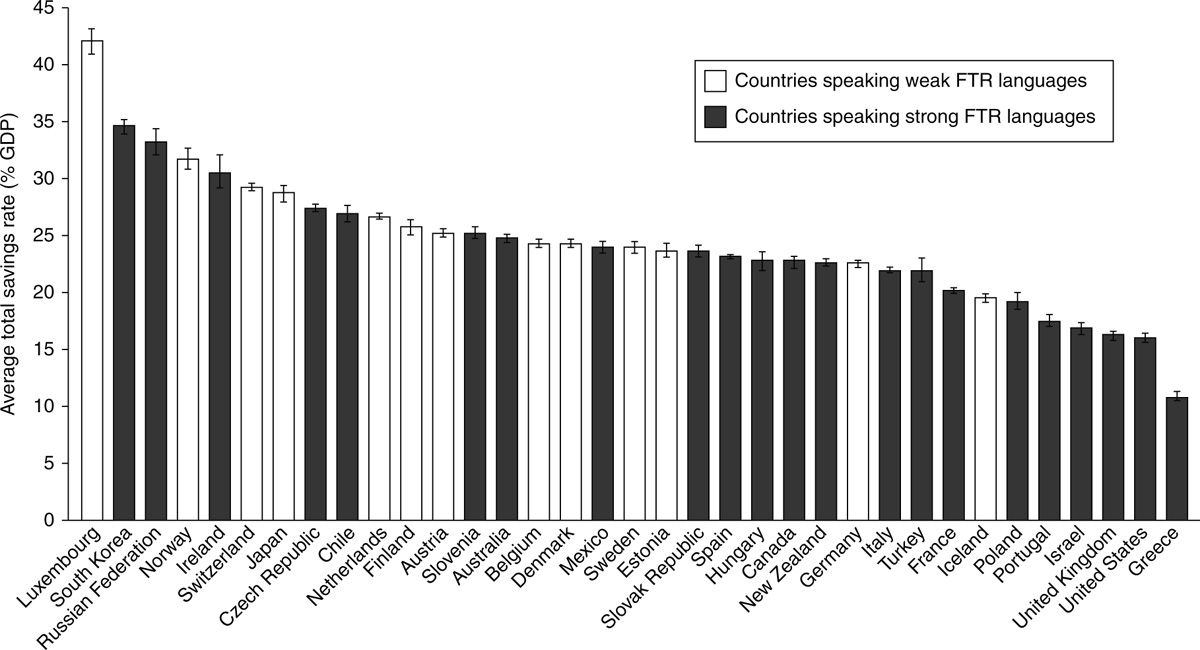

No, I’m afraid not. A swell graph of Chen’s allows us to find the actual truth. The dark bars are languages that mark the future pretty religiously, in the way that an English speaker thinks of as normal: for example, I walk, I walked, I will walk. The light bars are the languages where the future is largely left to context—which worldwide, is actually quite common.

Chen presents the graph as showing that future-marking languages cluster among the countries with lower savings rates. Already, we see that despite the statistical fact that countries with future-marking languages save 4.75 percent less, the overall picture leans discomfitingly toward a rather scattered distribution of dark and light bars—some light ones amid the dark, and lots of dark ones amid the light. The statistics show the reality? Sure—but only if the linguistic analysis is solid. And it happens not to be.

Chen, although making a diligent effort to consult the grammars, was misled by the fact that ultimately, grammars can be unreliable when it comes to explaining whether or not a language “marks the future” as regularly as English does. For example, Chen has Russian as a future-marking language. And indeed, you can get that impression from a grammar of Russian that devotes itself to telling an English speaker that you express the future by doing x, y, and z. However, Russian does not have anything you could call a future marker in the sense of English will or the future tense conjugations you might recall in French and Spanish.

Figure 4.1: OECD Savings Rates, 1985-2010

Note: On average, countries that speak strong FTR languages save 4.75% less. t = 2.77, p = 0.009

It is part of learning Russian, in fact, to wrap your head around expressing the future by implying it, through bits of stuff that mean other things. It wasn’t for nothing that literary critic Edmund Wilson once ventured—possibly having drunk in some Whorfianism—that Russians’ inability to be on time was because Russian doesn’t have a future tense.

Even English is like this to an extent: one says We’re buying the Honda Civic, where we express something we will do in the future with the construction called the present progressive. Imagine someone asking, “So, what’s going on about the car you want to buy?” If you respond, “We will buy the Honda Civic,” you likely learned English last night.

In Russian, the future usually piggybacks this way on something else. The details are oppressive and, here, unnecessary, but suffice it to say that while in English the big distinction is between now, then, and later, in Russian the big distinction is between “flowing along” and “bang, right then,” whether in the past, present, or future. The future, in Russian, is largely expressed as one of various takes on “bang, right then.” So, ja pisal means “I was writing,” that is, flowing along writing. But add na- and say ja na-pisal and it means “I wrote”—right then. Tell someone to write something (right now) and you say Na-pishi! In the same way, to say “I will write” you use that same na- bit and say Na-pishu. The idea is that you are not talking about just writing along, over a period of time—rather, you mean you will start some writing. Right now, writing will start.

But this means that in Russian, there is no marker you can think of as being specifically for expressing the future. Russian offers no table of future tense endings to learn. A Russian struggles to explain to an English speaker what “the future in Russian” is, typically resorting to just giving examples like na-pishu whose endings, in terms of conjugation, are in the present tense. True, you can use the be verb to say “I’ll be writing”—ja budu pisat’. This is the kind of thing Chen likely came across. But that’s a highly secondary, also-ran kind of future—go back to the Honda conversation and imagine some poor soul saying, “I will be buying the Honda Civic.” Only now and then do you need to say such things. Overall, to learn Russian as an English speaker is to ask, at some point, “How, exactly, do you put a verb in the future?”

So that means that on Chen’s chart, the Russian bar should be white. Now, as it happens, if it were white, that would be good for Chen, because Russians are actually good savers. For him, Russian as a future-marking language is something he has to classify as “noise,” because his idea is that languages that mark the future make their speakers save less money. But this actually creates more, not fewer problems.

Russian is part of a family of languages, the Slavic brood, that largely all work the same way. The facts on the future are the same for Czech, Slovak, and Polish. Predictably from his take on Russian, Chen codes all of them as future marking. Yet on his chart, Czechs are good savers (another problem even under his analysis), while Poles are bad ones, and Slovaks are somewhere in between.

This leaves Chen in a muddle no matter how we parse the data. We might say that even if Russian and friends don’t have a word or prefix like will that is only for future, they do require a speaker to do something to make the future, even if that something can also be used for other things. So, we could say that calling them nonfuture languages is splitting hairs. But then, why are Russian, Czech, Slovak, and Polish spread all the way across the grid? Shouldn’t they, if grammar shapes thrift, cluster?

But then if we accept that these four languages are not future marking and should all be white, then that distribution is still a fatal flaw. What is Polish, in particular, doing way over on the right with the bad savers, when Poles (as I have confirmed in exchanges with a Polish speaker while writing this) have the same hard time telling an English speaker how to “make a verb future” as Russians, and for the same reason? We might add that Czech and Slovak are essentially the same language—why would their speakers be so many bars apart if we are really seeing a meaningful correlation between grammar and having the discipline to save?

Meanwhile, Slovenian is also a Slavic language and, as it happens, it does have an actual future-marking construction. But on Chen’s chart, aren’t Slovenians a little too far leftward in the thrifty realm for people with a future-marker that supposedly should be discouraging them from socking funds away for a rainy day?

And there’s some more. For example, Korean, too, requires an English speaker to give up the idea of a “future marker.” Nothing in Korean corresponds to will—Chen may have gotten an impression otherwise from a suffix that is translatable as roughly “could” or “might.” But that’s not will.

Whether we keep the four Slavic bars black or white, their spreading all the way across the thriftiness grid, in combination with the Korean problem, renders Chen’s chart a randomness. Ultimately, it comes down to this. Given how Chen’s chart actually corresponds with the grammars in question—such as that future-marking Slovenian is right next to Anglophone Australia but twenty-one bars leftward of the Anglophone United States—how plausible is it that the reason savings rates in the United States have been so low has anything at all to do with the word will?

The Dog That Doesn’t Bark

When a Study Shows a Negative

And so it goes. Even attempts to show links between what Chinese does have and how Chinese people think run aground. We have already seen how fragile the results are from investigating whether Mandarin’s month below means that Mandarin speakers sense time as vertical in any significant way. In addition, an analogous problem has cropped up regarding something else present, rather than absent, in Mandarin. This time it’s the same kind of markers of material that we saw in Japanese with the Nivea experiment.

In Japanese, when there’s a number, recall, you have to stick in a little word that differs depending on what something is like. Two hiki of dogs, but two hon of beers, and so on. Chinese has the same “bubble”: two zhī of dogs, two tiáo of rivers, and many more. To an extent, these little words correspond to actual qualities of the thing in question—for many animals, for many skinny things. However, they spill beyond that, to the extent that overall, speaking the language means just knowing which little word to use with which word, just “because.” For example, why in Mandarin is it both two bă of scissors and two bă of umbrellas? You just have to live with it.

Yet Whorfianism entails that Mandarin speakers must think of scissors and umbrellas as alike on a certain level regardless, because—drum roll, please—language shapes thought. And then in other languages with little words like this that you have to use after numbers, they apply in alternately random ways. Remember how Japanese’s hon, used with beer, is also used with things as unlike as pencils, phone calls, and movies? Whorfianism, then, also leads one to expect that speakers of other languages with such little words must mentally group things that happen to take the same one of them, such as Japanese—or Thai, where you say both two tua of eels and two tua of tables.

But in fact, speakers of such languages do not group objects that way. A study has shown that Mandarin speakers are as likely to feel scissors and eels alike as scissors and umbrellas, despite that in Mandarin, while scissors and umbrellas both require bă, eels, as skinny things, require tiáo. Meanwhile Thais are as likely to group eels and umbrellas as eels and tables, despite that in their language both eels and tables take tua while umbrellas take a different marker khan.

This study shows, quite simply, that despite Mandarin and Thai speakers using little words each indexed to often random assemblages of nouns day in and day out, they do not end up processing those objects as akin on any deep level. To wit, to speak Mandarin is not to be a human being who sees scissors and umbrellas as somehow alike in a way that any other rational human being would.

And in the end we must ask whether that is a surprise. It is no more one than that it doesn’t add up that Mandarin speakers go around less aware of the difference between what is and what could be than English speakers. Languages differ. Thought doesn’t. Or, if it does, it’s because of cultural factors that are conditioned by—wait for it!—culture. Not grammar.

![]()

The Whorfian impulse will resist. Surely the data are not yet all in. But what are data? The relevant data here are “Start start God achieve make sky earth” and “If you see I sister you know she pregnant get.” Billions—literally billions, if we count the speakers of Mandarin, the other Chinese varieties, and the innumerable similar languages spoken in East and Southeast Asia—of human beings speak in exactly that way day in and day out, and have since time immemorial.

Cherish Whorfianism as showing that all people are cognitively advanced, or even cognitively interesting. But then admit that an imposing clutch of languages tend to relegate the obvious to the blankness of implication. And then try again to embrace the idea that language shapes thought. Studies show that it does—or better, that it can. Somewhat.

But is that “somewhat” robust enough that in light of what her grammar is like, we could tell a Mandarin speaker she’s a bit of a dummy?