The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition (2016)

B

Baal: (![]() ). “Lord/Master/Husband.” The chief active god of the Canaanite, Ugaritic, and Phoenician pantheons. A god of thunder and fertility, several biblical authors considered him YHVH’s chief rival for the loyalties of the people Israel. The Bible sometimes speaks of “baalim” in the plural. This may reflect the common custom of identifying a local spirit with Baal. Thus, in different places, the Bible mentions a Baal Hadad and a Baal Pe’or (“the lord god of Hadad” and “the lord god of Pe’or”).

). “Lord/Master/Husband.” The chief active god of the Canaanite, Ugaritic, and Phoenician pantheons. A god of thunder and fertility, several biblical authors considered him YHVH’s chief rival for the loyalties of the people Israel. The Bible sometimes speaks of “baalim” in the plural. This may reflect the common custom of identifying a local spirit with Baal. Thus, in different places, the Bible mentions a Baal Hadad and a Baal Pe’or (“the lord god of Hadad” and “the lord god of Pe’or”).

Baal ha-Chalom: (![]() ). “Lord of Dreams.” Based on Job 33:14-18, Judaism identified an Angel of dreams (Otzer Geonim 4). The name of the angel varies from source to source. In the Talmud, it can also refer to a professional oneiromancer (Ber. 56a-b). SEE Angel And Angelology; Divination; Dream; Sar Ha-Chalom.

). “Lord of Dreams.” Based on Job 33:14-18, Judaism identified an Angel of dreams (Otzer Geonim 4). The name of the angel varies from source to source. In the Talmud, it can also refer to a professional oneiromancer (Ber. 56a-b). SEE Angel And Angelology; Divination; Dream; Sar Ha-Chalom.

Baal ha-Sod: (![]() ). “Master of secrets.” A general, nontechnical moniker for a teacher of Jewish esoteric traditions.

). “Master of secrets.” A general, nontechnical moniker for a teacher of Jewish esoteric traditions.

Baal [Baalat] Ov: (![]() ). “Master [Mistress] of Ov.” A Necromancer. This term first appears in the Bible in a list of forbidden occupations (Deut. 18). An ov is a familiar, a term that may be derived from Akkadian. It is also possible, though less likely, that an ov is a dead ancestral spirit. In that case the word is being derived from the Hebrew avah, “father,” the Arabic aba, “return,” or aabi, Hittite for “grave.” 1 According to the Talmud, a Baal Ov is a medium who causes the dead to speak, either through his own Body or, in the Mesopotamian custom, through a skull (Sanh. 65b; Shab. 152b-153a; Josephus, Ant. 4:4). SEE Death; Divination; Ghost; Medium; Necromancer And Necromancy; Possession, Ghostly; Xenoglossia And Automatic Writing.

). “Master [Mistress] of Ov.” A Necromancer. This term first appears in the Bible in a list of forbidden occupations (Deut. 18). An ov is a familiar, a term that may be derived from Akkadian. It is also possible, though less likely, that an ov is a dead ancestral spirit. In that case the word is being derived from the Hebrew avah, “father,” the Arabic aba, “return,” or aabi, Hittite for “grave.” 1 According to the Talmud, a Baal Ov is a medium who causes the dead to speak, either through his own Body or, in the Mesopotamian custom, through a skull (Sanh. 65b; Shab. 152b-153a; Josephus, Ant. 4:4). SEE Death; Divination; Ghost; Medium; Necromancer And Necromancy; Possession, Ghostly; Xenoglossia And Automatic Writing.

1. Schmidt, Israel’s Beneficent Dead, 150-52; Roth, Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 3, 114.

Baal Shem: (![]() ). “Master of the [Divine] Name.” An informal title given to wonderworkers and/or saints. From earliest Judaism it was believed that the Names of God, but most often the Tetragrammaton, could be manipulated for theurgic or magical purposes. The Talmud also teaches that truly Righteous persons have the power to bend God’s will to their own (M.K. 16b). Such people were sometimes called anshei ma’aseh, “men of [wondrous] deeds.”

). “Master of the [Divine] Name.” An informal title given to wonderworkers and/or saints. From earliest Judaism it was believed that the Names of God, but most often the Tetragrammaton, could be manipulated for theurgic or magical purposes. The Talmud also teaches that truly Righteous persons have the power to bend God’s will to their own (M.K. 16b). Such people were sometimes called anshei ma’aseh, “men of [wondrous] deeds.”

The term “Baal Shem” for a wonderworker, however, is early medieval in origin. Though it was sometimes applied to religious poets, most people designated Baal Shems as either folk healers who used Segulah or Segulot cures, rainmakers, or the manufacturers of amulet. Some achieved fame as exorcists.1

Many writers used the term pejoratively, as synonymous with “quack” or “charlatan.” Even a marginal figure like Abulafia, Abraham looked down upon them. Some books of their cures and incantations, such as Miflaot Elohim (“The Wonders of God”), have been published in the modern era. The most famous of all Baalei Shem is Israel ben Eliezer, the founder of Chasidism.

1. Scholem, Kabbalah, 310-11.

Baal Shem Tov: SEE Israel Ben Eliezer.

Baaras: A location in Israel which yields a mysterious magical root uniquely effective in extracting demons, if one can overcome its lethal touch while harvesting it (War 7:180-185).

Baba Sali: Kabbalist and wunder-rabbi (Moroccan, ca. 20th century). He was famous for his healing powers. His gravesite in southern Israel is still a popular place of pilgrimage.

Babel, Tower of: SEE Babel, Tower Of.

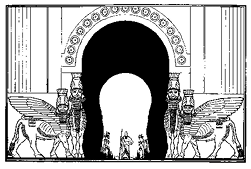

Babylon: (![]() ). Derived from Akkadian: Bab-ilum, “Gate of Heaven.” An ancient city-state empire centered in what is now Iraq. Supposedly founded at the command of the god Marduk, this city became the place of Jewish exile after 586 BCE. Babylon was a culture permeated with supernatural beliefs and magical practices. Under its hegemony in the years following the destruction of Jerusalem, Jews became increasingly preoccupied with such matters. Astrology, divination, the use of amulet, and the practice of Magic in a variety of forms, all became more pervasive folkways among Jews living in Iraq and Persia. Referring to the country as Bavel or Shinar interchangeably, the Bible repeatedly ridicules the pretensions of the Babylonians, especially in the fable of the Babel, Tower of (Gen. 11).

). Derived from Akkadian: Bab-ilum, “Gate of Heaven.” An ancient city-state empire centered in what is now Iraq. Supposedly founded at the command of the god Marduk, this city became the place of Jewish exile after 586 BCE. Babylon was a culture permeated with supernatural beliefs and magical practices. Under its hegemony in the years following the destruction of Jerusalem, Jews became increasingly preoccupied with such matters. Astrology, divination, the use of amulet, and the practice of Magic in a variety of forms, all became more pervasive folkways among Jews living in Iraq and Persia. Referring to the country as Bavel or Shinar interchangeably, the Bible repeatedly ridicules the pretensions of the Babylonians, especially in the fable of the Babel, Tower of (Gen. 11).

The Gates of Babylon with guardian Lamassu

Bachya ben Asher: Mystical Bible commentator (Spanish, ca. 13th-14th century). A student coming out of the circle of Nachmanides, his works include many occult teachings and esoteric interpretations of biblical episodes. Bachya particularly believed in the theurgic power of the commandment—that their proper performance empowered God, while Sin weakened God’s power in the world.1

1. M. Idel, Kabbalah: New Perspectives (New Haven, CT: Yale Press, 1988), 162-64.

Backwards: SEE Reversal (Magical).

Bahir, Sefer ha-: “The Book of Illumination.” This document is the most influential early book in what would become the classical Kabbalah of the Middle Ages. Though written in a Midrashic style and credited with great antiquity, it is more likely the work of early medieval Provencal mystics. Like the earlier Yetzirah, Sefer, the Bahir is deeply immersed in the supernal power of words and letters and wordplay and creative philology plays a major role in its esoteric oeuvre. The first description of the sefirotic Tree of Life appears in its pages. The concept of reincarnation is introduced in the form of cryptic parables. It is also one of the first works to treat the mundane nomina of the Bible as allegories for metaphysical realities. Thus, according to the Bahir, “Abraham” is really the divine attribute of love, and his saga recorded in Scripture is actually an Allegory for how God’s love functions in the created realms. It expounds on divine names and their magical uses, as well as how to theurgically activate divine power through the performance of commandments.1

1. Dan and Kiener, The Early Kabbalah, 28-31; A. Green, Guide to the Zohar (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), 16-18.

Bakol: (![]() ). The daughter of Abraham. Her existence is derived from reading the verse, “And God blessed Abraham with

). The daughter of Abraham. Her existence is derived from reading the verse, “And God blessed Abraham with ![]() [everything] (Gen. 24:1)” as a pun: how could he have everything if he didn’t have a daughter? (B.B. 47b, 16b; Gen. R. 59:7). The Bahir (78) regards her to be a supernal entity, either an angelus interpres, wisdom, or the Shekhinah, who grants Abraham insight into the cosmic order (Zohar I:223a. Also see Nachmanides’ and Bachya’s comments to Gen. 24:1).

[everything] (Gen. 24:1)” as a pun: how could he have everything if he didn’t have a daughter? (B.B. 47b, 16b; Gen. R. 59:7). The Bahir (78) regards her to be a supernal entity, either an angelus interpres, wisdom, or the Shekhinah, who grants Abraham insight into the cosmic order (Zohar I:223a. Also see Nachmanides’ and Bachya’s comments to Gen. 24:1).

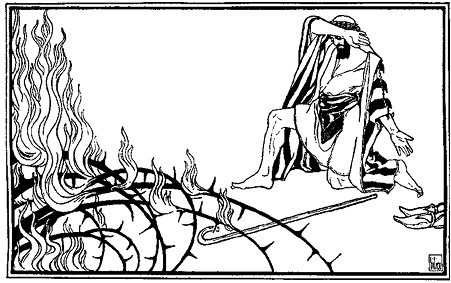

Balaam ben Beor: Ancient gentile seer from Transjordan. An extended story about Balaam appears in Numbers 22-24. Balaam is summoned by the King of Moab to collectively curse the Israelites. Being on good terms with YHVH, Balaam initially refuses, but is eventually induced to go help the king. Riding on an ass to join the king, he is confronted by a Sword-wielding Angel. Once he arrives, rather than cursing Israel, he is instead possessed by God and pronounces four extended blessing oracles upon them.

Gnostics declared Balaam to be a Prophet of the High God of goodness, and an enemy of the God of Israel, whom they equated with the evil Demiurge. They interpret the conflict of these two deities as the cause of Balaam’s various reversals of fortune. In the Midrash, Balaam is described as everything from a magician to a prophet. Based on the verse, “he knows the mind of the Most High” (Num. 24:16), one legend even declares him the greatest of the seven prophets God sent to the non-Jewish Nations, the gentile counterpart to Moses (B.B. 15b; Num. R. 20:1), perhaps even his superior (Sif. D. end). He is generally, but not consistently, portrayed as a wicked conspirator against Israel; he is credited with giving Pharaoh the suggestion to drown the Israelite children. Another tradition treats him as the most evil practitioner of Witch; he even derived his power by bestiality—copulating with his donkey (Sanh. 105a-b; Zohar I:126a). It was commonly held in the Middle Ages that Balaam was also a master of Astrology. Renderings of him in illuminated manuscripts often showed him holding an astrolabe. Raziel, Seferclaims he knew the workings of the divine Chariot (B.B. 15b; Tanh. Balak; A.Z. 4a-b; Avot 5).

Baladan: (![]() ). “Not a Man.” A dog-faced demons mentioned in rabbinic literature (Sanh. 96a) and the Zohar, Sefer ha- (I:6b). The name is evidently derived from the biblical character, Merodach-Baladan (1 Sam. 39:1; 2 Kings 20:12). Isaac Safrin may also be referring to these same imps when he speaks of the “evil dog” who works against humanity (Megillat Saterim).

). “Not a Man.” A dog-faced demons mentioned in rabbinic literature (Sanh. 96a) and the Zohar, Sefer ha- (I:6b). The name is evidently derived from the biblical character, Merodach-Baladan (1 Sam. 39:1; 2 Kings 20:12). Isaac Safrin may also be referring to these same imps when he speaks of the “evil dog” who works against humanity (Megillat Saterim).

Balsam: (![]() /Bosem). The juice of this plant is extracted for medicinal and perfumery uses. It may also have been an ingredient in the Incense burned in the Temple. In the World to Come, thirteen streams of balsam oil will flow for the pleasure of the Righteous (Tan. 25a; Gen. R. 62:2; Zohar I:4b; Zohar II:127a). SEE Herbs And Vegetables; Pharmacopoeia.

/Bosem). The juice of this plant is extracted for medicinal and perfumery uses. It may also have been an ingredient in the Incense burned in the Temple. In the World to Come, thirteen streams of balsam oil will flow for the pleasure of the Righteous (Tan. 25a; Gen. R. 62:2; Zohar I:4b; Zohar II:127a). SEE Herbs And Vegetables; Pharmacopoeia.

BaN: (![]() ). An acronym for “52,” a divine name appearing in Chayyim, Sefer ha-’s Etz Hayyim. The name is YHVH if each letter were given its full (malei) spelling: Yud H-H Vav H-H. It is sometimes used in a meditative permutation exercise.

). An acronym for “52,” a divine name appearing in Chayyim, Sefer ha-’s Etz Hayyim. The name is YHVH if each letter were given its full (malei) spelling: Yud H-H Vav H-H. It is sometimes used in a meditative permutation exercise.

Baneman: Yiddish, “changeling.” A wood-and-straw doll that demons substitute for a living infant. The parents are enchanted so as to perceive the doll as living, while the actual infant is taken and raised to serve infernal forces (Toldot Adam sec. 80). SEE Banim Shovavim.

Banim Shovavim: (![]() ). “Mischievous Sons.” Originally used to describe wayward children (Jer. 3:22; Chag. 15a), it took on a supernatural interpretation, being used to refer to changelings who are the offspring of human-demonic couplings. The concept can be seen in biblical interpretations of Cain that assume he had dual parentage through both Adam and the edenic serpent (Chochmat ha-Nefesh, 26c), whom the Talmud suspects copulated with Eve:

). “Mischievous Sons.” Originally used to describe wayward children (Jer. 3:22; Chag. 15a), it took on a supernatural interpretation, being used to refer to changelings who are the offspring of human-demonic couplings. The concept can be seen in biblical interpretations of Cain that assume he had dual parentage through both Adam and the edenic serpent (Chochmat ha-Nefesh, 26c), whom the Talmud suspects copulated with Eve:

When Adam, doing penance for his sin, separated from Eve for 130 years, he, by impure desire, caused the earth to be filled with shedim, lilin, and evil spirits. (Gen. R. 20; Eruv. 18b)

Incubi and succubae presumably continue to haunt men and women, appropriating their procreative powers to replenishing the ranks in every generation.

There seem to be two threads to this tradition. One assumes that such demonoid beings are the seemingly normal people who reveal their hybrid natures when they engage in heinous acts, while the other envisions these “sons” as spirits. All these creatures are a threat to the moral children of their parent and the demonic offspring must be redeemed by means of a graveside ritual of incantations and magical Circle (Tikkun Shovavim).1 SEE Demons; Nocturnal Emission.

1. G. Scholem, On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism (New York: Schocken, 1965), 154-56.

Banquet, Messianic: (![]() ). “The Meal of Leviathan.” Inspired by Job 41:6, one of the most popular mythic images of the reward awaiting the Righteous in the World to Come is the Seudah shel Livyatan, the messianic banquet (PdRE 10). There the great Chaos monsters, Ziz, Behemoth, and Leviathan, will finally be slaughtered for the enjoyment of all. In one version of this legend, there were originally two Leviathans. God killed the first in primordial times and salted away the meat for the banquet. The other sea monster will be served fresh (B.B. 74b; PR 16:4, 48:3; Mid. Teh. 14:7). The banquet appears in Akdamut, the 11th-century poem sung on the holiday of Shavuot:

). “The Meal of Leviathan.” Inspired by Job 41:6, one of the most popular mythic images of the reward awaiting the Righteous in the World to Come is the Seudah shel Livyatan, the messianic banquet (PdRE 10). There the great Chaos monsters, Ziz, Behemoth, and Leviathan, will finally be slaughtered for the enjoyment of all. In one version of this legend, there were originally two Leviathans. God killed the first in primordial times and salted away the meat for the banquet. The other sea monster will be served fresh (B.B. 74b; PR 16:4, 48:3; Mid. Teh. 14:7). The banquet appears in Akdamut, the 11th-century poem sung on the holiday of Shavuot:

And each righteous one under his canopy will sit,

In the Sukkah made from the skin of Leviathan,

And in the future

He will make a dance for the righteous ones,

And a banquet in Paradise,

From that Leviathan and the Wild Ox,

And from the wine preserved from the Creation—

Happy are those who believe and hope and

Never abandon their faith forever!

The subtext of this myth is that in messianic times the last forces of destruction, Chaos , and entropy will finally be swept away, and the world will achieve its perfect state.

Bar Hedya (or Hadaya): Talmudic oneiromancer (ca. 4th century). He is portrayed as a man of doubtful character whose interpretations depended on the amount of money paid him. The story of Bar Hedya also features a humorous episode about one of his predictions that came to pass: Rava was told by Bar Hedya that his dream signified he would be hit twice with a club. The Sage is in fact later attacked, but averts a third blow by declaring to his attacker, “Enough! I saw only two [blows] in my dream!” This suggestive story may help explain Bar Hedya’s maxim, “All dreams follow the interpretation.” In other words, dream interpretations are no more than self-fulfilling prophecies (Ber. 56a-b).

Bar Jesus: A Jewish magician mentioned in the Christian Scriptures (Acts 13:6-11).

Bar Nifli: ( ![]() ). “Son of the Clouds.” A messianic figure, based on the book of Daniel (7:13), described in IV Ezra, Babylonian Talmud, and Targum Yerushalmi. SEE Messiah.

). “Son of the Clouds.” A messianic figure, based on the book of Daniel (7:13), described in IV Ezra, Babylonian Talmud, and Targum Yerushalmi. SEE Messiah.

Bar Yochai: (![]() ). A gigantic Roc-like bird mentioned in Talmud (Bik. 57a; Yoma 80a; Suk. 5a-b). Some stories of this bird overlap those of the Ziz.

). A gigantic Roc-like bird mentioned in Talmud (Bik. 57a; Yoma 80a; Suk. 5a-b). Some stories of this bird overlap those of the Ziz.

Baradiel: (![]() ). “Hail of God.” The Angel of Hail (I Enoch). He is one of the “seven wondrous, honored princes” and governs the third Heaven (III Enoch).

). “Hail of God.” The Angel of Hail (I Enoch). He is one of the “seven wondrous, honored princes” and governs the third Heaven (III Enoch).

Baraita de Yosef ben Uziel: This esoteric commentary on Yetzirah, Sefer, pseudepigraphically ascribed to the authorship of the mysterious Joseph ben Uziel, grandson of the prophet Jeremiah, was an important text created within the mystic Circle of the Unique Cherub.1

1. Dan and Kiener, The Early Kabbalah, 24; Also see Dan, The ‘Unique Cherub’ Circle, 59-79.

Baraita mi-Pirke Merkavah: “Tradition from the Chapters of the Chariot.” A book of Ma’asei-Merkavah.

Barakiel or Baraqiel: (![]() ). “Lightning of God.” The Angel of lightning (I Enoch, PdRE 8, Zohar II:252b). One of the “Seven Princes” of Heaven (III Enoch).

). “Lightning of God.” The Angel of lightning (I Enoch, PdRE 8, Zohar II:252b). One of the “Seven Princes” of Heaven (III Enoch).

Barkayal: The Fallen Angels who taught Astrology to humanity (I Enoch 8).

Barminan: (![]() ). “Far from Us.” An expression meant to ward off the evil eye (think in terms of the Prayer of the rabbi in Fiddler on the Roof: “God, bless and keep the Czar—far away from us!”). It can also be used as a euphemism for a dead Body.

). “Far from Us.” An expression meant to ward off the evil eye (think in terms of the Prayer of the rabbi in Fiddler on the Roof: “God, bless and keep the Czar—far away from us!”). It can also be used as a euphemism for a dead Body.

Barnacle Geese: Fantastic Birds thought to metamorphose from Shell. Christians used this creature as an Allegory for Jewish conversion to Christianity (a humble shellfish can be transformed into a beautiful bird). Jewish versions of the barnacle geese legend have them growing on Trees (Zohar III:156).

Barrenness: SEE Fertility.

Baruch, Apocalypse of or Book of: A cluster of pseudepigraphic works, with different versions existing in Greek and Syriac, claiming to be Baruch ben Neriah’s firsthand accounts of the destruction of the earthly Jerusalemand his ascension to the heavenly Jerusalem. In one vision, Jerusalem is actually destroyed by angelic forces rather than Babylonians. Then the sacred vessels of the Temple are secreted away, after which the spirit of Prophecy seizes Baruch and he experiences eschatological visions. This is how the Syriac version ends. The Greek version picks up with Baruch ascending bodily into the Seven Heavens, where he sees fantastic visions of the past, the future, hell, and the celestial workings. Both versions, though evidently of Jewish origin, have been so heavily reworked by Christian writers that it is difficult to tell what is original and what has been superimposed on the text over time.1

1. Metzger and Coogan, The Oxford Companion to the Bible, 76-77.

Baruch ben Neriah: Secretary to the prophet Jeremiah (ca. 6th century BCE). Like many other peripheral characters that appear in Scripture, Baruch becomes a prominent figure in Jewish occult tradition. He becomes the protagonist of the Apocalypse of Baruch. The Rabbis identify him with the character Ebed Melech mentioned in the book of Jeremiah, making him an Ethiopian (PdRE 53). Counted as a Prophet by some Sages, later legends claim his Body experienced a saintly Death untouched by decay. His grave was a place of highest sanctity; like the Ark of the Covenant, those who touched it died. Other stories have him ascend bodily into Heaven, like Elijah. (Meg. 14b, 15a; Sif. Num. 99; II Baruch). SEE Righteous, THE.

Baruch She ‘Amar: ( ![]() ). A liturgical hymn recited on the Sabbath morning. Consisting of ten stanzas, Chayyim, Sefer ha- taught that one should contemplate the ten sefirot in sequence with the singing, an act of elevating the Soul through intention. The Prayer serves as a pivot point in Luria’s model of the four world worship, for it is the prayer that lifts the worshipper beyond the world of Asiyah into the higher state of Yetzirah (Sha’ar Kavvanot I). In time the Lurianic siddur, Nusach ha-Ari, adopted a thirteen-stanza version of the hymn, to mirror the thirteen divine attributes (Ex. 34).1

). A liturgical hymn recited on the Sabbath morning. Consisting of ten stanzas, Chayyim, Sefer ha- taught that one should contemplate the ten sefirot in sequence with the singing, an act of elevating the Soul through intention. The Prayer serves as a pivot point in Luria’s model of the four world worship, for it is the prayer that lifts the worshipper beyond the world of Asiyah into the higher state of Yetzirah (Sha’ar Kavvanot I). In time the Lurianic siddur, Nusach ha-Ari, adopted a thirteen-stanza version of the hymn, to mirror the thirteen divine attributes (Ex. 34).1

1. M. Hallamish, Ha-Kabbalah b’Tefillah, b’Halakhah, uv’Minhag (Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 2000), 33.

Bashert: (u![]() ). “Destiny.” A term for something perceived as inevitable, or meant to be. This term has a decidedly positive connotation, and is most often used in reference to a good Wedding match.

). “Destiny.” A term for something perceived as inevitable, or meant to be. This term has a decidedly positive connotation, and is most often used in reference to a good Wedding match.

Bat: Not mentioned in the Bible, in rabbinic literature the bat is a shape-shifting creature that takes a number of forms over time but eventually morphs into a demons (B.K. 16a). SEE Animals.

Bat Kol: (![]() ). “Daughter of a Voice/[Heavenly] Echo.” A minor form of revelation described in Talmud and later Jewish literature:

). “Daughter of a Voice/[Heavenly] Echo.” A minor form of revelation described in Talmud and later Jewish literature:

Our Rabbis taught: Since the death of the last prophets, Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi, the Holy Spirit departed from Israel; yet they were still able to avail themselves of the Bat Kol. Once when the rabbis met in the upper chamber of Gurya’s house at Jericho, a Bat Kol was heard from Heaven, saying: “There is one amongst you who is worthy that the Shekhinah should rest on him as it did on Moses, but his generation does not merit it.” The Sages present set their eyes on Hillel the Elder. (Sanh. 11a)

Not prophetic in the prescient sense, instead it proclaims God’s will, judgment, or in the above example, God’s regret (Ber. 3a).

It appears most famously in the miraculous duel between Rabbi Eliezer and the Sages (B.M. 59b; J. Ber. 2). It sometimes is heard extolling the Righteous at the time of their death, and will be heard by the newly resurrected when they arise from the grave (Zohar I:118a). By the Middle Ages, it becomes equated with attaining a mystical state of communion (Kuzari 3:11). SEE Prophecy And Prophets; Vision.

Batraal: A Fallen Angels mentioned in I Enoch, chapter 7.

Batya: (![]() ). “Daughter of Yah.” The daughter of Pharaoh, she adopted the infant Moses. Later she repudiates Idolatry and marries the Israelite Caleb (1 Chron. 4:15, 18). One interpretation concludes she had the spirit of Prophecy in her and knew she was raising an agent of God (Aggadat Yam Talmud). Others state she was at the river to treat her Leprosy and was moved by pure compassion to spare the child (Sot. 12b; Ex. R. 1:23). Regardless, this act of adoption meant God adopted her in return, earning her the name “daughter of Yah” (Lev. R. 1:3), and counted an Israelite (Meg. 13b). One oft-repeated tradition is that God miraculously extended her arm, ala Mr. Fantastic, to pull the child to safety. One claim puts her reach at 60 cubits (Bachya ben Asher’s comment to Exodus 2:5). She is one of the select few who ascended to Heaven without tasting Death. In Edenshe rules over one of the palaces of the righteous dead (Meg. 13a; Ex. R. 1, 18).

). “Daughter of Yah.” The daughter of Pharaoh, she adopted the infant Moses. Later she repudiates Idolatry and marries the Israelite Caleb (1 Chron. 4:15, 18). One interpretation concludes she had the spirit of Prophecy in her and knew she was raising an agent of God (Aggadat Yam Talmud). Others state she was at the river to treat her Leprosy and was moved by pure compassion to spare the child (Sot. 12b; Ex. R. 1:23). Regardless, this act of adoption meant God adopted her in return, earning her the name “daughter of Yah” (Lev. R. 1:3), and counted an Israelite (Meg. 13b). One oft-repeated tradition is that God miraculously extended her arm, ala Mr. Fantastic, to pull the child to safety. One claim puts her reach at 60 cubits (Bachya ben Asher’s comment to Exodus 2:5). She is one of the select few who ascended to Heaven without tasting Death. In Edenshe rules over one of the palaces of the righteous dead (Meg. 13a; Ex. R. 1, 18).

Beard: SEE Hair.

Beard of Faith: The beard that is described as adorning the “Ancient of Days” in Daniel. Since the “glory of the face is the beard” (Shab. 152a), the divine “beard,” whether assigned as an attribute to the Zeir Anpin or Atika Kadisha within the Pleroma, is part of the divine Glory and subject to elaborate, at time inscrutable, metaphysical speculation. It has thirteen locks (tikkunim), conduits for the thirteen divine attributes of Exodus 33 that stream into the material world, as well as the thirteen “rivers of balsam” that await the righteous in the World to Come (S of S 5:13; Zohar II:177a-b, 122b; Zohar III:130b, 139a-140b).1

1. P. Giller, Reading the Zohar: The Sacred Text of the Kabbalah (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 116-119.

Beelzebub: (![]() ). A demons. He is first mentioned as a Phoenician god in 2 Kings 1. His name probably derives from Ugaritic “Lord Baal,” though it is often translated as “Lord of Flies.” By Greco-Roman times he is a demon lord and he is mentioned in Christian Scriptures (Matt. 12:24-27). He may be the same as Belzebouel, who appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS).

). A demons. He is first mentioned as a Phoenician god in 2 Kings 1. His name probably derives from Ugaritic “Lord Baal,” though it is often translated as “Lord of Flies.” By Greco-Roman times he is a demon lord and he is mentioned in Christian Scriptures (Matt. 12:24-27). He may be the same as Belzebouel, who appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS).

Beer Shachat: (![]() ). “Well of Destruction.” A term derived from Psalm 55:24, it is one of the seven compartments of Gehenna, the destination of the “wicked Nations.” Kushiel is its principle Angel (Masechet Gehinnom).

). “Well of Destruction.” A term derived from Psalm 55:24, it is one of the seven compartments of Gehenna, the destination of the “wicked Nations.” Kushiel is its principle Angel (Masechet Gehinnom).

Behemoth: (![]() ). A mythical beast mentioned in Job 40:15-24 and Psalm 50:10, which calls him the first of God’s creations. Other sources insist he was created on the sixth day (Mid. Konen). Behemoth drinks up all the waters that flow from Paradise (PR 16:4, 48:3). He is so big he sits on a thousand mountains (Ps. 50:10; Zohar I:18b). His bones are hard as tubes of bronze and his limbs are like Iron rods.

). A mythical beast mentioned in Job 40:15-24 and Psalm 50:10, which calls him the first of God’s creations. Other sources insist he was created on the sixth day (Mid. Konen). Behemoth drinks up all the waters that flow from Paradise (PR 16:4, 48:3). He is so big he sits on a thousand mountains (Ps. 50:10; Zohar I:18b). His bones are hard as tubes of bronze and his limbs are like Iron rods.

At the end of time he will do battle with Leviathan, a battle neither will survive. In the World to Come, he will be an entrée at the messianic banquet (II Esdras 6:52; B.B. 74b; Lev. R. 13:3, 22:10; PdRE 11). In Zohar, the beast sometimes symbolizes the Shekhinah (Zohar I: 223b). Behemoth is often portrayed in medieval Jewish illuminated manuscripts as an ox of gigantic proportions. SEE Animals.

Beinonim: (![]() ). “The In-betweens/the Doubtful.” Starting in Talmud (Ber. 7a; R.H. 16b) and highlighted in III Enoch, it is the designation for those who are neither pious, tzadikim, nor evil, rashaim. The bulk of humanity, the Beinonim, are those whose Fate in the afterlife is still in question. The condition and rectification of the Beinonim is the topic of the first chapter of the Tanya, and serves as the premise for the chapters that follow. (Tanya, Sefer Shel Beinonim).

). “The In-betweens/the Doubtful.” Starting in Talmud (Ber. 7a; R.H. 16b) and highlighted in III Enoch, it is the designation for those who are neither pious, tzadikim, nor evil, rashaim. The bulk of humanity, the Beinonim, are those whose Fate in the afterlife is still in question. The condition and rectification of the Beinonim is the topic of the first chapter of the Tanya, and serves as the premise for the chapters that follow. (Tanya, Sefer Shel Beinonim).

Beit El Circle: This Jerusalem-based kabbalistic fellowship has been one of the most influential Jewish mystical movements among Sefardi and Hasidic Jews since its start under the leadership of the Yemenite mystic Shalom Sha’bari in the mid-18th century. The circle focuses on the teachings of Isaac Luria as recorded by Chayyim Vital. The academy that Sha’bari nurtured emphasized a curriculum of mixed Kabbalah, Talmud, and medieval philosophy. Arranged in around-the-clock “watches” so that study would be going on perpetually, the Beit El system cultivated in the adherents a vigorous lifestyle centered on study, Prayer, and contemplation. The adherents go so far as to wear two sets of tefillin simultaneously during daylight hours, in order to honor the differing practices of two famous sages. The circle continues into the 21st century.1

Prayer is the emphasized rite of the group, and the Beit El philosophy teaches the extensive use of kavvanot, ritualized concentration, in prayer, as well as contemplating divine names, as means to achieve devekut, union with God. The group has been usually preoccupied with the proper observance of the biblical system of shemittah and yovel, sabbatical and jubilee years.2

1. L. Jacobs, The Jewish Mystics (London: Kyle Cathie, 1990), 156-169.

2. Ibid.

Beit ha-Midrash, heavenly: SEE Yeshiva Shel Malah.

Beit Shean: This town at the south side of the juncture of the Jezreel and the Jordan valleys is the gate to Eden (Eruv. 19a).

Bela ben B’or: (![]() ). “Devourer Son of Consumption.” First of the eight Edomite kings who “ruled before there was a king in Israel” (Gen. 36:31-39). In the Lurianic creation myth, the “eight kings” are an Allegory, and Bela is Knowledge, the first vessel to shatter, releasing evil into the cosmos.

). “Devourer Son of Consumption.” First of the eight Edomite kings who “ruled before there was a king in Israel” (Gen. 36:31-39). In the Lurianic creation myth, the “eight kings” are an Allegory, and Bela is Knowledge, the first vessel to shatter, releasing evil into the cosmos.

Beli Ayin ha-Ra: (![]() ). “No evil eye!” An adjuration against witchcraft.

). “No evil eye!” An adjuration against witchcraft.

Belial: (![]() ). “Worthless.” Belial is a demons mentioned in the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), apocryphal books, and the Gospels. As is so often the case, the word appears in the Bible as an adjective, meaning “worthless” (1 Sam. 10:27) and/or rebellious person (Job 34:18), but in post-biblical tradition becomes reified as an entity, place, or supernatural force (see, for example, Abaddon and Ketev Meriri). Talmud Baba Batra 10a uses the word ambiguously, so that the reader could infer the term to mean either “worthlessness” or “devil.” Based on the Book of Jubilee’s description of him as the accuser and tempter (1:20. Also see Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, Reuben 2), Belial may be an alternative name for Samael, Satan, ha-Satan, or a conflation with both. In some medieval works, Belial gives birth to Armilus.

). “Worthless.” Belial is a demons mentioned in the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), apocryphal books, and the Gospels. As is so often the case, the word appears in the Bible as an adjective, meaning “worthless” (1 Sam. 10:27) and/or rebellious person (Job 34:18), but in post-biblical tradition becomes reified as an entity, place, or supernatural force (see, for example, Abaddon and Ketev Meriri). Talmud Baba Batra 10a uses the word ambiguously, so that the reader could infer the term to mean either “worthlessness” or “devil.” Based on the Book of Jubilee’s description of him as the accuser and tempter (1:20. Also see Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, Reuben 2), Belial may be an alternative name for Samael, Satan, ha-Satan, or a conflation with both. In some medieval works, Belial gives birth to Armilus.

Belimah: (![]() ). A term that may or may not first appear in Job 26:7, where b’li-mah seems to mean “emptiness.” As used in Sefer Yetzirah to refer to the sefirot prior to their unfolding, it means either “containment/restraint” (the divine restraint that pre-existed the Emanation) or “Silence” (the cosmic silence that preceded God’s first words, “Let there be light”).1 Other interpretations referencing the passage in Job, divide it into two words,

). A term that may or may not first appear in Job 26:7, where b’li-mah seems to mean “emptiness.” As used in Sefer Yetzirah to refer to the sefirot prior to their unfolding, it means either “containment/restraint” (the divine restraint that pre-existed the Emanation) or “Silence” (the cosmic silence that preceded God’s first words, “Let there be light”).1 Other interpretations referencing the passage in Job, divide it into two words, ![]() /b’li-mah, “without whatness,” in the sense of “without substance.” Thus Belimah becomes associated with Keter, the first emanation.

/b’li-mah, “without whatness,” in the sense of “without substance.” Thus Belimah becomes associated with Keter, the first emanation.

Other works, such as Baraita de Yosef ben Uziel, understand it as a reference to the ten metaphysical concepts the average Jew is forbidden to investigate: what is before Creation, after the judgment, the reward of the righteous, the punishment of the wicked, and the remotest ends of what is up, down, east, west, north, and south. As this encyclopedia reveals, this prohibition is mostly honored through the breach.

1. Green, Guide to the Zohar, 54; A. Kaplan, Sefer Yetzirah: The Book of Formation (New York: Samuel Weiser, 1978), 25-26.

Bell: Bells appear in a significant role only during biblical times, when the High priest was required to wear them on the hem of his Ephod (Seventy-Two of them according to the Talmud):

You shall make the robe of the ephod entirely of blue wool. Its collar shall be folded over within. It shall have a woven border around its opening … it may not be frayed. On its hem you shall make pomegranates of blue, purple, and scarlet wool, on its hem all around. Between them, there shall be gold bells all around … It must be on Aaron when he serves; so that its sound is heard when he enters the Holy before Adonai. (Ex. 28:31-35)

These bells served to placate or drive back the Guardian Angels (Sar ha-Panim) that surround the Ark of the Covenant when the high priest enters the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur (Az be-En Kol piyut). Lilith is compared to a “golden bell” that disturbs men in their Sleep (Gen. R. 18.4). Unlike Christian-based theurgic practices, bells do not appear to have been used much by Jewish practitioners.

Belomancy: The casting of arrows for the purposes of divination is well attested to in Semitic cultures surrounding Israel. Not only do Akkadian and Arabic documents refer to it, but archaeologists have found bronze arrowheads with the inscription chetz (arrow) on them. Since inscribing an arrow with the word “arrow” seems pointless, at least one scholar speculates that the word is meant as a pun of the Ugaritic word for “luck.” 1

The practice of belomancy is explicitly mentioned twice in Hebrew Scriptures, once with condemnation (Ezek. 21:26), the other as a legitimate way for a Prophet to discern the future (2 Kings 13:14-19). It is alluded to in another passage (1 Sam. 20:19-22). This third passage may be meant as satire, showing it (and the interpretation of word omen in general) to be nothing more than a sleight-of-hand trick to convey messages already known to the practitioner.

The methods of belomancy vary. According to Ezekiel, a bundle of arrows is shaken and then cast down, possibly in front of an Idol. The pattern in which they fall was presumably interpreted, I Ching fashion, by the baru (diviner). Arab sources suggest that arrows (usually three, just as described in the 1 Samuel passage) were shot, and the message then derived from the pattern of their landing.

1. Singer, The Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 2, 307; Roth, Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 3, 114-15.

Ben Azzai, Simon: Talmudic Sage and mystic (ca. 2nd century). Several sources report that when Ben Azzai expounded Torah, the flames of Sinai enveloped him:

Once, when Ben Azzai was interpreting Scriptures, flames blazed up around him, and when asked whether he was a student of the mysteries of the “Chariot of God,” he replied, “Like pearls, I string together words of the Torah with those of the Prophets; those of the Prophets with those of the Writings; and thus the words of the Torah rejoice as on the day when they were revealed in the flames of Sinai.” (Lev. R. 16; S of S R. 1.10)

He is one of the Four Sages who entered Pardes or PaRDeS. According to the account in Chagigah 14b, “He looked and died.” Genesis Rabbah takes this as a sign of his piety; for he is credited with saying that the pious see the rewards awaiting them in the moments before their Death. The Sages taught, “He who sees Ben Azzai in a dream is assured piety” (Ber. 57b).

Ben Stada: A practitioner of witchcraft mentioned in Talmud (B. Shab. 104b). He derived his knowledge from Egypt, one of the great sources of arcane knowledge (Sanh. 67a; Ka. 1:16).

Ben Temalion: A beneficent demon that helped a group of Jews, led by Simon bar Yochai, sent as emissaries to Rome. He did this by first possessing the daughter of Caesar, then allowing Bar Yochai to perform an exorcism on her. When Ben Temalion finally left her Body, Bar Yochai earned Caesar’s gratitude and his cooperation (Me. 17b). Among medieval Jews of the Rhineland, “ben Temalion” becomes an idiom for any mischievous spirit.1

1. Singer, The Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 2, 257.

Ben Zoma, Simon: Talmudic Sage and mystic (ca. 2nd century). He is one of the Four Sages who entered Pardes or PaRDeS. The experience drove him mad (Chag. 14b). Prior to this misadventure, Ben Zoma was noted for his obsession with Ma’asei-Bereshit, the mysteries of Creation. So powerful was his hold over the imagination of the Sages that the Talmud offers this promise, “He who sees … Ben Zoma in a dream is assured of wisdom” (Ber. 57b).

Bereshit: (![]() ). “When God Created …” This first word of the first book of the Bible serves both as the Hebrew name for the book Genesis and as an idiom for “Creation.” Because of its pride of position at the “start” of creation, as well as its uniqueness (the word never appears again in Scriptures), the word is subjected to intensive and varied exegetical analysis. Many, many meanings are derived from this one six-letter word.

). “When God Created …” This first word of the first book of the Bible serves both as the Hebrew name for the book Genesis and as an idiom for “Creation.” Because of its pride of position at the “start” of creation, as well as its uniqueness (the word never appears again in Scriptures), the word is subjected to intensive and varied exegetical analysis. Many, many meanings are derived from this one six-letter word.

Since the time of RaSHI, it has been widely understood that the conventional sequential translation, “In the beginning …” is inaccurate. Bereshit is a construct, not absolute form, so a temporal “When [God] began to …” is more accurate. So already on the merely syntactical level the word has its complexities. But Jewish tradition has also held the six letters contain secrets that the wise will understand. For example, by making a Notarikon (in this case, separating the word into two words, it yields:

![]() He created six [things] … (Gen. R. 1:4; MhG)

He created six [things] … (Gen. R. 1:4; MhG)

A secret is revealed—six critical entities preceded the actual creation of Heaven and Earth: The Throne of Glory [positive existence], Torah [the blueprint for existence], the ancestors [the righteous pillars that support existence], the concept of the Temple [the link between worlds], and the name of Messiah [redemption and rectification].

Although the Torah itself suggests that certain hylic entities coexisted with God at the beginning (water, darkness), by separating out the diacritical dagesh [it is the dot in the first letter] from the word and treating it as a metaphysical symbol, the exegete reads it as:

Beginning with a point … ![]() /b’ reshit], (Zohar I:15a)

/b’ reshit], (Zohar I:15a)

and from this the Zohar demonstrates the philosophic principle creation ex nihilo [from nothing] in the first word. The author of the Zohar also finds hints of the sefirotic structure in the first sentence, Bereshit bara Elohim:

With Wisdom [reishit = Chochmah, a claim based on Proverbs 8:22; 3:18], the Infinite [= Keter, the subject being implicit in the verb form bara] created Elohim [= Binah].

In a different vein, all Jewish mysticism takes very seriously the pathos (the caring) of God. Kabbalah emphasizes that God is driven by a “need” to create and relate to that creation, an idea scandalous to rationalist philosophy, which posits that God must be impassive. Rearranging the six letters yields a phrase that reveals that creation is a:

![]() /A song of desire (Attributed to Isaac Luria)

/A song of desire (Attributed to Isaac Luria)

and confirms the mystical premise of a deity longing for us.

These are just a few examples. Tikkunei Zohar alone has seventy d’rashot on the word Bereshit. But this kind of freeform interpretation creates other problems for the tradition. For example, Christians can play this game too. The six letters can be regrouped to spell out: father; son; fire [equaling the Holy Spirit, though the association seems tenuous]; fortunate daughter [i.e., the Virgin Mary]; even crucifixion on the sixth day. This last element is based on an alphabetically/morphological pun: the Hebrew Tav, the sixth letter in the word, is the equivalent of the Greek tau … which is cross-shaped (De Naturis Rerum, a commentary by 12th-century monk Alexander Neckham).

Christian exegetical demonstrations like this may in part explain the gradual Jewish shift to more contextual, plain-sense [Pashat] interpretations of the Hebrew Bible favored by later generations of commentators such as RaSHI, David Kimhi, and Sforno; contextual readings offer less chance of having one’s own hermeneutics used against one. SEE CHAOS; CREATION; MA’ASEI-BERESHIT.

Beriyah, World of: (![]() ). “Creation.” The second of the four worlds of emanation, this is the level in which positive existence emerges. It encompasses the “lower” worlds of Yetzirah and Asiyah. Some traditions associate this with the highest orders of Angels and the Throne of Glory. As the first world that is “created” rather than purely “emanated,” it is said to function as the first garment concealing the supernal shefa of God’s creative force. It is, nonetheless, a realm of pure intellect and the place from which human reason emanates. It is also the domain of pure law (Etz Chayyim). Jewish word mysticism also associates it with the first letter hay in the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God.

). “Creation.” The second of the four worlds of emanation, this is the level in which positive existence emerges. It encompasses the “lower” worlds of Yetzirah and Asiyah. Some traditions associate this with the highest orders of Angels and the Throne of Glory. As the first world that is “created” rather than purely “emanated,” it is said to function as the first garment concealing the supernal shefa of God’s creative force. It is, nonetheless, a realm of pure intellect and the place from which human reason emanates. It is also the domain of pure law (Etz Chayyim). Jewish word mysticism also associates it with the first letter hay in the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God.

Beruchim, Abraham: Kabbalist (North African, ca. 16th century). He advocated the mystical discipline of midnight study andPrayer. He was such a severe advocate of repentance that he was believed by many to be the reincarnation of the prophet Jeremiah.

Berudim: (![]() ). “Spots.” In the Lurianic cosmic-allegorical interpretation of Genesis 31:10, this refers to Yetzirah, the World of Emanation.

). “Spots.” In the Lurianic cosmic-allegorical interpretation of Genesis 31:10, this refers to Yetzirah, the World of Emanation.

BeSHT: SEE ISRAEL BEN ELIEZER.

Bestiality: Sexual relations with animals are explicitly forbidden by the Torah (Lev. 18). Stories of inter-species intercourse do, however, appear in Jewish literature. The most famous of these is a Talmudic reference to Eve copulating with the serpent (Shab. 146a). There is also a more obscure tradition that Adam first gave vent to his libido with God’s other creations, a story that serves as an etiological rationale as to why God felt compelled to create a female partner for him. One Midrash claims that antediluvian people engaged in bestiality with all the land creatures, thereby contributing to the absolute corruption of all Creation, requiring the great Flood to purge the Earth of this obscenity (Gen. 6; Eruv. 18b). Interestingly, as in Greco-Roman religions, such tales of bestiality are mostly set in the mythic past.

Bestiality is closely associated in the Talmudic imagination with witchcraft, and the Sages believed that it was through intercourse with animals that Balaam gained his infernal powers (Sanh. 105a-b; Zohar I:126a).

Thus in Talmud, there are several apparently earnest discussions as to whether a Jew should let a Pagan serve as a bailiff for Jewish livestock, out of fear the animals will be used for immoral/infernal purposes. It would be easy to assume that these are simply cases of Jews stereotyping their neighbors, but the fairly frequent representation of human-animal coupling on Greek pornographic urns might suggest and explanation for the Talmud’s preoccupation with this issue.1

1. S. Deacy and K. Pierce, eds. Rape in Antiquity: Sexual Violence in the Greek and Roman Worlds (London: Duckworth, 2002), 69-96. Also see P. Mathieu, Sex Pots: Eroticism in Ceramics (New York: A & C Black, 2003).

Bet: (![]() ). Second letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It has the numeric value of two. It is the first letter appearing in the Torah. According to Genesis Rabbah, the shape of the letter (closed above, below, and on one side, with only one side open) is meant to teach that a person should not engage in speculation about what is above, below, or precedes Creation; a lesson respectfully but more or less completely ignored by the author of this book. Based on its numeric value, it reveals that God created two worlds simultaneously:

). Second letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It has the numeric value of two. It is the first letter appearing in the Torah. According to Genesis Rabbah, the shape of the letter (closed above, below, and on one side, with only one side open) is meant to teach that a person should not engage in speculation about what is above, below, or precedes Creation; a lesson respectfully but more or less completely ignored by the author of this book. Based on its numeric value, it reveals that God created two worlds simultaneously:

Rabbi Yehudah ben Pazzi explained according to Bar Kappara: Why was the world created with a bet? To teach you there are two worlds: this world and the world to come. Another interpetation: Why [begin] with a bet? Because bet is the language of berachah/”blessing.” And why not with an alef? Because alef is the language of arur/”cursing.” (Gen. R. 1.9)

According to Deuteronomy Rabbah, the bet at the beginning of Torah (with its value of 2) teaches us about the inherent duality of Creation (2:31).1

1. Munk, The Wisdom of the Hebrew Alphabet, 43-54.

Beth (or Beit) Alfa: This archaeological site of an ancient synagogue (ca. 4th-5th century CE) is most notable for the richly decorated mosaic floor consisting of numerous Jewish motifs surrounding an elaborate zodiac at the center. The most puzzling element of this display is that Helios, the Greek god of the sun, is clearly represented there in the hub of the design.1

1. M. Avi-Yonah, The Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (London: Oxford University Press, 1975), 187-90.

Beth El: “House of God.” The location, near biblical Luz, where Jacob had his dream of a stairway to Heaven (Gen. 29). It would later become a sacred center for the early cult of YHVH. The story of Jacob’s dream may have been meant to provide an etiology for why the shrine was established at that location.

Betulah: (![]() ). “Virgin”/Virgo.” The zodiac sign for the month of Elul. This sign signifies the Earth, night, sensuality, materiality, and the feminine principle.1

). “Virgin”/Virgo.” The zodiac sign for the month of Elul. This sign signifies the Earth, night, sensuality, materiality, and the feminine principle.1

1. Erlanger, Signs of the Times, 99-120.

Bezalel: (![]() ). “In the Shadow of God.” This Israelite craftsman, “filled with the spirit of God,” was primarily responsible for the construction of the tabernacle (Ex. 24-25). Bezalel was identified as a gifted artisan in the Bible, and legends of his fantastic skills multiplied.

). “In the Shadow of God.” This Israelite craftsman, “filled with the spirit of God,” was primarily responsible for the construction of the tabernacle (Ex. 24-25). Bezalel was identified as a gifted artisan in the Bible, and legends of his fantastic skills multiplied.

So great was his insight into God’s intention that the Sages dubbed him the R’aiah, the Seer, along with other honorific names. Bezalel built the tabernacle according to a heavenly pattern shown to him. He could do this because he knew how to manipulate the Hebrew alphabet to unleash its supernal powers, just as God used them to create the universe (Ber. 55a; Zohar I: 9a). This legend is related to the widely held belief that the tabernacle was itself a model of the cosmos (Num. R. 12:13). The medievals credited his talent as a metallurgist to his knowledge of Alchemy.

Bible: (![]() /TaNaKH also

/TaNaKH also ![]() /mikra). TaNaKH is an acrostic for the three divisions of the Hebrew Scriptures: Torah, Neviim, and Ketuvim (Pentateuch, Prophets, and Writings). This arrangement also roughly reflects the decreasing degree of divine inspiration credited to each book, with Torah being the most direct of God’s revelations and the Writings generally credited to the more modest influence of the Ruach Elohim, the “Holy Spirit.” The Hebrew Scriptures consist of thirty-nine canonical books (there are other methods of counting the collection, including treating the twelve minor prophets as a single book). The authoritative collection emerged out of a little-understood and mysterious process of canonization, a canonization not completed until at least the end of the 2nd century CE.

/mikra). TaNaKH is an acrostic for the three divisions of the Hebrew Scriptures: Torah, Neviim, and Ketuvim (Pentateuch, Prophets, and Writings). This arrangement also roughly reflects the decreasing degree of divine inspiration credited to each book, with Torah being the most direct of God’s revelations and the Writings generally credited to the more modest influence of the Ruach Elohim, the “Holy Spirit.” The Hebrew Scriptures consist of thirty-nine canonical books (there are other methods of counting the collection, including treating the twelve minor prophets as a single book). The authoritative collection emerged out of a little-understood and mysterious process of canonization, a canonization not completed until at least the end of the 2nd century CE.

The Bible also mentions within its pages several other mysterious lost books. These include the Book of Jashar, the Book of the Wars of the Lord, and the royal chronicles of both Judah and Israel.

Like any other Jewish tradition, Jewish esoteric traditions look to ground themselves and justify their teachings in the authority and authenticity of Scripture. And certainly, the Hebrew Bible provides plenty of obvious examples of the fabulous: Angels, giants (Gen. 6), miraculous staves (Ex. 7), and monsters (Ps. 74). But the logic of the occult assumes that for all the wonders and forces that are visible and revealed, there are much more powerful things in the text which are concealed and must be detected. There are multiple proof texts for this premise, such as Psalm 62, “One thing God has spoken, two things I have heard,” and Proverbs 25:2: “It is the glory of God to conceal a matter; to search out a matter is a glory of kings” (Also see Job 28; Prov. 25:11; Deut. 29:28). Thus, before the rise of Protestantism with its hermeneutic conceit that the meaning of the Scriptures was mono-vocalic, explicit, and self-evident, the Bible was widely regarded by both Jews and Christians to be a cryptic text: multi-vocalic, filled with layers of meanings, occult secrets, and powers that had to be extracted hermeneutically, or filled with teachings not meant for the masses. These secrets are concealed in the laws and stories by means of hints, allusions, allegories, and are even encoded into the very language itself. In fact, the more difficult the message was to ascertain, the more precious it was to be considered.1

This perception of the Bible as an exoteric text is illustrated in a famous legend that the Earth trembled when Onkelos the Proselyte and Jonathan ben Uziel first translated the Scriptures from the Holy Tongue (Hebrew) into popular Aramaic. When Ben Uziel further dared to make explicit the esoteric meanings embedded in Scriptures through his translations, a heavenly voice ordered him to stop (Meg. 3a; En Yaakov).

Evidence that the words of Scripture were held to have numinous and apotropaic powers already begins in biblical times, as indicated by the discovery of metal amulets inscribed with the Priestly Blessing (“The Lord bless and guard you …”) dating from the Monarchy period. Tefillin and mezuzahs, both of which contain biblical texts, were similarly credited with offering protection to their users (Ber. 23b; S o S R. 3:7; Num. R. 12). Reciting Psalm 91 came to be regarded as the first line of defense against demons. In the Middle Ages, a scroll or book of Scriptural verses would be placed at the head of a crib to protect an infant.

Despite the words of Rabbi Akiba, who declared that all those who use Bible verses for spells have no place in the World to Come (M. Sanh. 10:1), many biblical verses, such as Exodus 15:26, were used as healing incantations. In order to heal a seriously ill person, one might look in a book of Scripture, take the first word the eye falls upon, and add that word to the ailing person’s name. Biblical names, words, and phrases appear on virtually every inscribed amulet. Perhaps the most frequently used verses in a theurgic context are Genesis 49:18, Zechariah 3:2, and Numbers 6:24-26. Psalms were particularly popular in this regard. An entire book, Shimmush Tehillim, “Useful Psalms,” is devoted to cataloging verses for treating various conditions.

Passages would also be recited over crops to increase fertility and over property to protect it. According to Chayyim Vital, one can read and pronounce Scripture in such a way that it draws down an Angel that grants the summoner further revelations of secrets contained in the text (Sha’ar ha-Nevuah 2).

In classic magical fashion, verses were often read both forward and in reverse, or in permutations. Scriptures can also be used for purposes of divination. SEE BIBLIOMANCY; CODES; HEBREW AND HEBREW ALPHABET; PSALMS;TEMURAH; TORAH; TZERUF/Tzerufim.

1. J. Kugel, How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture (New York: Free Press, 2007), 14-16. Also see F. Talmage, “Apples of Gold: The Inner Meaning of Texts in Medieval Judaism,” in Jewish Spirituality, A. Green, ed., vol. 1 (New York: Crossroad, 1994), 313-355.

Bibliomancy: (![]() /Sheilat Sefer). Using sacred Scriptures as a means of divination. Above and beyond the familiar interpretative tradition that finds references to current events in the words of the Prophets. This kind of interpretation can be found in the pesher commentaries found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. And, of course, it is still a popular way to interpret the book of Revelations among some contemporary Evangelical Christians.

/Sheilat Sefer). Using sacred Scriptures as a means of divination. Above and beyond the familiar interpretative tradition that finds references to current events in the words of the Prophets. This kind of interpretation can be found in the pesher commentaries found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. And, of course, it is still a popular way to interpret the book of Revelations among some contemporary Evangelical Christians.

A verse can also be selected at random in the hopes of receiving an ominous message (Chag. 15a; SA Yoreh Deah 179:4). Some Sages believed in the mantic science of kleidon, treating the serendipitous overhearing of verses recited by school children as omens :

Says Rabbi Johanan, “It is clear that I have a Master in Babylon; I must go and see him.” So he said to a child, “Tell me the verse you have learnt.” He answered, “Now Samuel was dead.” Said [R. Johanan], “This means that Samuel has died.” But it was not the case; Samuel was not dead then, and [this revealed] only that R. Johanan should not trouble himself [to go]. (Chul. 95b; also see Git. 58a)

The Baal Shem Tov compares the Bible to the Urim and Thummim as a potential source of mantic knowledge (Sod Yakhim u’Vo’az).

Binah: (![]() ). “Understanding/Insight.” In the sefirotic system, Binah is the offspring and compliment to Chochmah. It is the dark receptacle of Chochmah’s light, the female counterpart to its masculine principle (Zohar III:290a), though in principle it also holds “masculine” qualities. It suckles the lower worlds. As such, it is also called Ima, “Mother,” and Heichal, “Palace.” It is the womb of God’s light, giving birth to all the “lower” sefirot.1 Binah is one of the root aspects of the Tree of Life. It is also, however, the beginning of judgment because it is the beginning of division (Bahir 186). In the context of Jewish ritual, Binah is associated with the Holy Ark, which contains the Torah. Removing the Torah from its concealment activates the divine flow from Binah to Tiferet (Or ha-Yashar).

). “Understanding/Insight.” In the sefirotic system, Binah is the offspring and compliment to Chochmah. It is the dark receptacle of Chochmah’s light, the female counterpart to its masculine principle (Zohar III:290a), though in principle it also holds “masculine” qualities. It suckles the lower worlds. As such, it is also called Ima, “Mother,” and Heichal, “Palace.” It is the womb of God’s light, giving birth to all the “lower” sefirot.1 Binah is one of the root aspects of the Tree of Life. It is also, however, the beginning of judgment because it is the beginning of division (Bahir 186). In the context of Jewish ritual, Binah is associated with the Holy Ark, which contains the Torah. Removing the Torah from its concealment activates the divine flow from Binah to Tiferet (Or ha-Yashar).

1. H. Eilberg-Schwartz, ed. People of the Body: Jews and Judaism from an Embodied Perspective (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1992), 119-120.

Binush, Binyamin, of Krotoszyn: (Polish, 1660?-1730). Wandering Baal Shem and author of two books: a magical manual, Sefer Amtachat Binyamin, and a collection of Lurianic healing Prayers, Shem Tov Katan. He was famed for his efficacious amulets, especially ones for the protection of women during and after childbirth.

Birds: (![]() /Tzipor; Oaf ). Birds are a symbol of immortality and the Soul. Studying the behavior of birds was a form of divination most popular among the Hittites.1 Since biblical times, Jews have also regarded birds as portending the future. According to one strand of tradition, human souls take the form of birds in Heaven (Baruch Apocalypse 10; SGE). The Vilna Gaon, in his mystical interpretation of the book of Jonah, also teaches that a dove symbolizes the transmigrating human soul. SEE ANIMAL; HOOPOE; MILHAM BIRD; PHOENIX; ZIZ.

/Tzipor; Oaf ). Birds are a symbol of immortality and the Soul. Studying the behavior of birds was a form of divination most popular among the Hittites.1 Since biblical times, Jews have also regarded birds as portending the future. According to one strand of tradition, human souls take the form of birds in Heaven (Baruch Apocalypse 10; SGE). The Vilna Gaon, in his mystical interpretation of the book of Jonah, also teaches that a dove symbolizes the transmigrating human soul. SEE ANIMAL; HOOPOE; MILHAM BIRD; PHOENIX; ZIZ.

1. Hallo and Younger, The Context of Scripture, 206; Roth, Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 3, 114.

Bird’s Nest: SEE PALACE OF THE BIRD’S NEST.

Birth: SEE CHILDBIRTH

Birth Pangs of the Messiah: (![]() /Chevlei ha-Mashiach). This refers to the various tribulations and disturbances—political, social, and cosmic—that precede the coming of the Messiah (Shab. 118a; Sanh. 98a).

/Chevlei ha-Mashiach). This refers to the various tribulations and disturbances—political, social, and cosmic—that precede the coming of the Messiah (Shab. 118a; Sanh. 98a).

Bitachon, Sefer ha-: This esoteric work by the little-known Iyyun Circle includes passages on the creation of a golem.

Bitter Destruction: (![]() /Ketev Meriri). The demons of catastrophe is identified from biblical passages (Deut. 32:24; Ps. 91:6; Isa. 28:2). He is featured in a discussion of having a fortunate nature:

/Ketev Meriri). The demons of catastrophe is identified from biblical passages (Deut. 32:24; Ps. 91:6; Isa. 28:2). He is featured in a discussion of having a fortunate nature:

Abaye was walking. Rav Papa was on his right and Rav Huna was on his left. He saw Ketev Meriri approaching him on his left—he had Rav Papa and Rav Huna switch sides. Rav Papa said, “Why aren’t you concerned for me?” [Huna replied] “Your Mazel is good now.” (Pes. 111a-b)

His power is greatest between the seventeenth of Tammuz, the date when the walls of Jerusalem were breached by the Romans, and the ninth of Av, the day the Temple was destroyed. He is scaly and hairy and rolls about like a ball. His gaze brings instant Death (Num. R. 12.3, 7:9; Me’am Loez).

Bittul ha-Torah: (![]() ). “Nullification of (precepts) of the Torah.” In general, this is regarded as a bad thing, and Jews are forbidden to engage in any activity that is so distracting from engagement with Torah it effectively crowds it out of one’s life (A.Z. 18b; Tos. Shab. 7.5; Tos. A.Z. 2.2). In certain Haredi and Hasidic circles, this can be applied quite restrictively, effectively prohibiting any “secular” pursuit at all.

). “Nullification of (precepts) of the Torah.” In general, this is regarded as a bad thing, and Jews are forbidden to engage in any activity that is so distracting from engagement with Torah it effectively crowds it out of one’s life (A.Z. 18b; Tos. Shab. 7.5; Tos. A.Z. 2.2). In certain Haredi and Hasidic circles, this can be applied quite restrictively, effectively prohibiting any “secular” pursuit at all.

Bittul ha-Yesh/Bittul ha-Nefesh: (![]() ).“Nullification of the Ego/Selfhood.” This can mean a range of self-negating conditions from total submission to God’s will to ego-annihilation. Since the ego stands as an impediment between the Soul and God, Chasidic teachings encourage the spiritual seeker to sublimate or even overthrow the self in order to achieve devekut, unification with the true reality that is God.1

).“Nullification of the Ego/Selfhood.” This can mean a range of self-negating conditions from total submission to God’s will to ego-annihilation. Since the ego stands as an impediment between the Soul and God, Chasidic teachings encourage the spiritual seeker to sublimate or even overthrow the self in order to achieve devekut, unification with the true reality that is God.1

1. Rabinowicz, The Encyclopedia of Hasidism, 48; A. Green, Jewish Spirituality, vol. 2 (New York: Crossroad, 1986), 181-91.

Black: SEE COLOR.

Blasphemy: ( ![]() /Birkat ha-Shem [euphemism]). While the Torah prohibits insulting God (Lev. 24:10-23), the exact parameters of this offense are unclear. In Jewish tradition the offense of blasphemy is limited to one who pronounces the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) for the purpose of profaning it (M. Sanh. 7.5; Sanh. 56a). In the Bible, the punishment could include Death, but that has been nullified since Talmudic times. The Mishnah statement on the matter, “Let YHVH curse YHVH,” makes the issue so puzzling, it becomes legally impossible to define or enforce. The Gospel accounts that claim Jesus was condemned by a Jewish court for “blasphemy” for calling himself son of God has no basis in any known Jewish law (M. Sanh. 7:5), suggesting the charge may be the Gospel writer’s own invention.

/Birkat ha-Shem [euphemism]). While the Torah prohibits insulting God (Lev. 24:10-23), the exact parameters of this offense are unclear. In Jewish tradition the offense of blasphemy is limited to one who pronounces the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) for the purpose of profaning it (M. Sanh. 7.5; Sanh. 56a). In the Bible, the punishment could include Death, but that has been nullified since Talmudic times. The Mishnah statement on the matter, “Let YHVH curse YHVH,” makes the issue so puzzling, it becomes legally impossible to define or enforce. The Gospel accounts that claim Jesus was condemned by a Jewish court for “blasphemy” for calling himself son of God has no basis in any known Jewish law (M. Sanh. 7:5), suggesting the charge may be the Gospel writer’s own invention.

Blessed Holy One: (![]() /ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu). A title for God popularized in Talmudic times, in Kabbalistic thought “The Blessed Holy One” designates the specifically male aspect of the Pleroma and it is identified with the sefirah of Tiferet. SEE NAMES OF GOD; SEFIROT.

/ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu). A title for God popularized in Talmudic times, in Kabbalistic thought “The Blessed Holy One” designates the specifically male aspect of the Pleroma and it is identified with the sefirah of Tiferet. SEE NAMES OF GOD; SEFIROT.

Blessing: (![]() /B’rachah). The capacity to bless something belongs foremost to God (Gen. 1, 12). A human may also bless, but with the understanding, either explicitly stated (“May it be Your will …”) or implied, that the power of blessing comes from the Deity. Because a blessing is the exercise of divine power, even if humans utter it, Jewish literature regards blessings to have real consequences (Gen. 28, saga of Esau and Jacob). Though Isaac intended the blessing he spoke over Jacob for Esau, once it was given, it could not be rescinded. In this sense a blessing is also more like an adjuration or decree of destiny than a Prayer. The fact that humans have the capacity to bless is a sign of our exalted status in the cosmos (Meg. 15a; Ber. 7a; Chag. 5b).

/B’rachah). The capacity to bless something belongs foremost to God (Gen. 1, 12). A human may also bless, but with the understanding, either explicitly stated (“May it be Your will …”) or implied, that the power of blessing comes from the Deity. Because a blessing is the exercise of divine power, even if humans utter it, Jewish literature regards blessings to have real consequences (Gen. 28, saga of Esau and Jacob). Though Isaac intended the blessing he spoke over Jacob for Esau, once it was given, it could not be rescinded. In this sense a blessing is also more like an adjuration or decree of destiny than a Prayer. The fact that humans have the capacity to bless is a sign of our exalted status in the cosmos (Meg. 15a; Ber. 7a; Chag. 5b).

As is the case with so many other aspects of Jewish practice, the Zohar eroticizes blessing, claiming its existence only flow through the union of male and female forces (III:74b). The theme of drawing down blessing through the sefirot via the sexual act becomes a recurrent theme is later Kabbalistic teachings.1 SEE CURSE.

1. M. Idel, Kabbalah and Eros (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 122, 183, 205-206.

Blood: (![]() /Dam). Blood is considered the essence of life, full of numinous qualities, and the handling of blood is of tremendous concern to God:

/Dam). Blood is considered the essence of life, full of numinous qualities, and the handling of blood is of tremendous concern to God:

And whatsoever man there be of the house of Israel, or of the strangers that sojourn among them, that eats any blood, I will set My face against that person that eats blood, and will cut him off from among his people. For the life of the meat is in the blood; and I have given it to you upon the altar to make atonement for your lives; for it is the blood in the living thing makes atonement [for consuming them]. Therefore I said unto the Children of Israel: No person of you shall eat blood, neither shall any stranger that sojourns among you eat blood. (Lev. 17:11-12)

For that reason, many taboos and laws concerning blood are found in Jewish law (Lev. 19:26; M. Ker. 5:1; Yad, Ma’achalot Asurot 6:2). The sprinkling of blood from the sacrifices upon the altar was an element in the rituals of atonement and purification, and blood resulting from slaughter for food had to be poured out on the ground and covered over (Lev. 17:13). The Torah expressly forbids the use of blood for divination (Lev. 19:26).

It is the first of the plagues God unleashes upon Egypt—every body of water , from the sacred Nile to the cooking kettles, was turned to blood and defiled. Blood also has protective power against numinous forces, as demonstrated during the Exodus from Egypt (Ex. 12:7, 12:22-23). Medieval physiology held that menstrual blood (niddah) was transferred/transformed into mother’s milk during and following gestation.

The Jewish awe regarding blood continued to have a paranormal aspect—the Zohar develops a dichotomous metaphysic around the symbolism of blood of circumcision (symbolizing purity) and blood of menstruation (symbolizing impurity). It also offers a contrast between the “blood of Jacob” and the “blood of Esau,” a polemical mirror image of the emerging Spanish obsession with limpieza de sangre, blood purity of lineage.1 Jewish men were particularly in awe of the weird and frightening power of menstrual blood, a fascination with a strongly misogynistic tone. One medieval tradition held that menstruating women who gaze into mirrors will leave blood marks on the glass.

As alluded to above, blood from sacrifices and food slaughtering must be poured out on the ground and covered, a means of legitimizing the taking and consumption of animal life through a rite of acknowledgment, “returning” the “life” to its maker and legitimate owner. Subsequent Jewish law requires that Jews go to great lengths to extract blood from animal carcasses, first hanging the animals for draining, then soaking and salting the flesh afterward to draw out any additional blood. This taboo about eating blood has meant that blood is not a regular materia magica used in Jewish magical formulae, rituals, or potions. Occasional exceptions appear in magical manuals such as Sefer ha-Razim, where we learn lion’s blood, mixed with wine and rubbed on the soles of the feet, gives one persuasive power over princes. Later religious authorities, usually drawing from non-Jewish sources, start to permit blood as an ingredient in therapeutic formulae (Shevut Yaakov II: 70).

Ironically, the Jewish attitude of aversion to blood may have inspired Christian anti-Semites to regard Jews as blood obsessed and even blood lusting. Among American folklorists, the custom of hanging slaughtered animals and draining the blood practiced among Hispanics of the Southwest is taken as evidence of Crypto-Jewish occult folkways.2 SEE BLOOD LIBEL.

1. D. Biale, Blood and Belief: The Circulation of a Symbol between Jews and Christians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 106-107.

2. J. Neulander, “The New Mexican Crypto-Jewish Canon: Choosing to be ‘Chosen’ in Millennial Tradition,” Jewish Folklore and Ethnology Review 18, no. 12 (1996): 140-58.

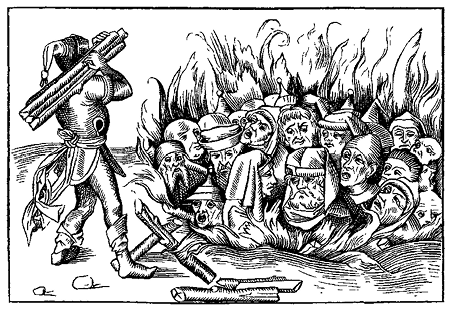

Blood Libel: The claim that Jews kill gentiles motivated by ritual/demonic impulses. While accusations of Jews engaging in ritual murder go as far back as the 1st century CE (Against Apion 2, viii 95), in what amounts to a remarkable disregard of all the evidence that Jews loathed the consumption of blood, medieval Christian superstition held that Jews, vampire-like, craved the blood of innocent Christians. This accusation, now known as a “blood libel,” enjoyed great currency in Christian circles from the Middle Ages until well into the 20th century, though it was sporadically debunked by Church authorities.1

Early versions of the libel claimed Jews would steal the consecrated host from church sacristies and then perform satanic rituals upon the bread in order to make it bleed. Because Easter was the time of Jesus's death, the rumor then arose that Jews ritually reenacted the death of Christ by killing an “innocent,” usually a child, and using the child’s blood for the making of matzah for Passover. The first such accusation occurred in Norwich, England, in the 12th century. A long series of similar accusations arose across Europe in the centuries that followed. The purported Christian victims were frequently beatified, while the Jews accused mostly met manifold gruesome ends, the manners of death being limited only by the local imagination.

Woodcut of the mass execution of Jews in Nuremberg, 1493

During the Black Death plagues of the 14th century, it was widely believed that Jews were spreading the contagion by poisoning the wells used by Christians, leading to numerous savage persecutions across Europe. Actual trials of Jews for ritual murder peaked during the 18th century.

A Russian clerk, Menachem Mendel Beilis, was the last Jew tried for the crime of ritual murder in 1911 (he was acquitted). In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Catholic newspapers revived the charge against Jews as part of a campaign to combat the liberal, socialist, and democratic ideas then sweeping Europe (Jews were seen as central players in these infernal ideologies). Partly as a result, accusations continued to arise in Catholic countries in the first half of the 20th century.2 Gleefully promoted by the Nazis in the 1930s-40s,the blood libel is enjoying a new life in the Arab world, where the media and leaders in Syria and Saudi Arabia periodically claim that demonic Jews are filled with (literal) blood lust directed at non-Jews.3

1. J. Trachtenberg, The Devil and the Jews (Philadelphia, PA: JPS, 1943), 140-58.

2. D. Kertzer, The Popes Against the Jews: The Vatican’s Role in the Rise of Modern Anti-Semitism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001).

3. “Top Hamas Official Osama Hamdan: Jews Use Blood for Passover Matzos,” MEMRITV, Clip No. 4384 (transcript), July 28, 2014, http://www.memritv.org/clip/en/0/0/0/0/0/0/4384.htm.

Blue: SEE COLOR.