The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition (2016)

J

Jachin and Boaz: ( ![]() ). Two bronze pillars on the exterior of Solomon's Temple. Along with the other pillar, Boaz, it was erected before the door to the sanctuary:

). Two bronze pillars on the exterior of Solomon's Temple. Along with the other pillar, Boaz, it was erected before the door to the sanctuary:

And he [Solomon] erected the pillars for the portico of the sanctuary, and he erected the right-hand pillar and called it “Yachin,” and he erected the left-hand pillar and called it “Boaz.” (1 Kings 7:21)

The significance of the two named pillars on the portico of the Temple is never explained in the Hebrew Bible, and remains the Sod ha-Sodot, the mystery of mysteries, connected to the great structure.

These two bronze pillars, topped with curved capitals and festooned with a decorative motif of rimmonim (pomegranates) and shushan (lily?), are a genuine puzzle. The complex instructions concerning the capitals, in particular, using terms that appear nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible, introduce considerable uncertainty as to the final appearance of the pillars. Moreover, it seems that the pillars served no structural function, making them, as we would say today, “architectural features,” purely decorative objects. The fact that they are each named adds to the confusion, as the significance of the names (“foundation” and “strong”) is not self-evident. The obvious conclusion is that these were symbolic in nature. But the exact meaning of the symbolism has eluded most commentators.

One solution is that they are a vestigial element from Pagan temple design. There is evidence that Canaanite and Phoenician temples had exterior pillars. The lily motif is one seen on other pillars in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Overlapping this is the idea that they are representation of the divine phallus, symbols of power, vitality, and fertility, though the presence of two structures confuses the issue.

Scholar Jon Levenson argues the Temple is meant to be a microcosm of the world at its Edenic, pristine phase, a “model,” as it were, of the creation process (“The Temple and the World” 297). One can see this idea more explicitly acknowledged in Ezekiel 47, where the messianic temple resembles Eden, complete with four rivers flowing from its precincts. The Temple exemplifies the world at its primordial origin, the ideal cosmos. Therefore, just as the the Molten Sea basin in the courtyard symbolizes the constrained primeval waters, the pillars would be something paired within the paired process of forming the universe (notice in the Genesis 1 account, the world is formed out of paired merisms—light and dark, water above and below, land and sea, etc.). Thus they are either the [implied] pillars that hold up the heavens, the cherubs who guarded Eden (Gen. 3), or the two trees that sat at the center of the garden, the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Yet the correspondence between the Genesis narrative and the Temple pillars is not absolute. If they symbolizes cherubs, why pillars at all, especially when cherubs decorate the interior of the building? and if they invoke the trees, why not more centrally located in the structure? And Genesis does not explicitly mention pillars as a feature of creation. Still, the Genesis account of the creation is not the only one found in the Hebrew Bible (Pss. 74, 104; Job 38-40), each of which offer several similar, but hardly identical, descriptions. Ancient myths tend to have multiple, variant iterations.

The traditional commentaries offer several explanations for the names. Perhaps this most plausible is this one by David Kimchi:

He named the pillars to make a good omen. They were at the entrance to the Temple, and he called them by names to make a good omen. He called one “Yachin,” meaning “establishment,” that the Temple should be established forever, like the phrase, “Like the moon, it should be established forever.” “Boaz,” meaning “strength,” a contraction of “Bo Oz” [“strength within”], meaning that God would put strength and endurance, in it, as it is written, “Adonai will give strength to His people.” (Comment to 1 Kings 7:21)

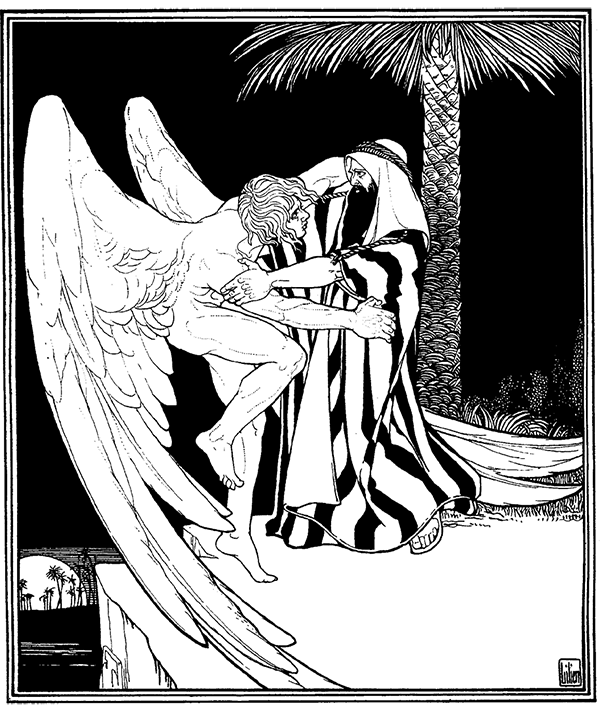

Jacob (also Israel): Biblical Patriarch, the son of Isaac. He was father to twelve sons who would be the founding fathers of the twelve tribes of Israel. In the Bible, Jacob experiences two major supernatural events, his dream vision of the ladder between heaven and Earth (Gen. 28) and his mysterious nighttime wrestling match with a man/angel by the river Yabbok (Gen. 32), at which time he is renamed “Israel” (“one who wrestles with God”).

In rabbinic legend, there are even more supernatural dimensions to Jacob’s life. Given the biblical account, it is not surprising that most of them revolve around Angels. When Jacob stole the birthright by deceiving his blind father Isaac, Isaac tried to curse him, but angels prevented this. At this time, Jacob purloined the garments of Adam which were then in Esau’s possession. When he wore them, they emitted the scent of Eden (PdRE 32; Zohar I:142b).

Jacob and Rachel by E. M. Lilien

When Jacob had his dream-vision of the heavenly ladder, he also received apocalyptic revelations. In one version, he actually ascended to the top of the ladder and from there caught a glimpse of the celestial temple (Gen. R. 56:10, 79:7; Sif. D. 352; PdRK 21:5; Tanh. Ve-Yetzei).

When Jacob wrestled with the angel, it was Esau’s guardian angel he battled (Gen. R. 77:2; Tanh. Va-yishlach). Another tradition claims it was his own guardian angel, Israel (PdRE 36). Angels also served as Jacob’s messenger to his brother Esau at the time of their reconciliation. Esau was so intimidated by this manifestation of the heavenly host that he immediately abandoned his plans to kill his brother. Later in life, Jacob’s arrival in Egypt brought an end to the famine his son Joseph had been battling. He died by the kiss of God.

The Zohar, building upon a tradition that Jacob resembled Adam (B.B. 58a), goes further in suggesting that Jacob took on all the most beautiful of Adam’s features—and perhaps he was even a reincarnation of the first soul (Zohar I:142b).

In early Jewish mysticism, Jacob is considered the most perfect of the Patriarchs, almost angelic (Ps. 134:5; Gen. R. 76:1; PdRE 35; Mid. Teh. 8:6). For that reason, his image is inscribed on the Throne of Glory, a fact alluded to in the Bible: “And upon the likeness of the throne was a likeness of a man” (Ez. 1:26). Midrash ascribes to him divine status in God’s eyes (Meg. 18a). All this, plus the fact that there is an angel with his name (Israel), suggests there may be a now-forgotten tradition of Jacob undergoing angelification (Gen. R. 74:17; Tos. Sot. 10:9; B.B. 17a).

The Zohar regards him to be the personification of Tiferet, the balancing force between the Chesed of Abraham and the Gevurah of Isaac (Zohar I:138a; Zohar II:259a; ZCh 57a).

Jacob ben Jacob ha-Kohen: Kabbalist (Spanish, ca. 13th century). Along with his brother, Isaac ben Jacob, he is the author of a popular mystical tract on the power of the Hebrew alphabet. SEE KABBALAH.

Jacob Isaac the Seer of Lublin: Chasidic master and wonderworker (Polish, ca. 18th-19th century). A celebrated figure in his own lifetime, he possessed the power to predict the future. He could also recount the past incarnations of the souls of the people he met. Because of these divinatory feats he was called the “Urim and Thummim.” Unfortunately, his powers escaped him at a critical moment, for he believed the Napoleonic Wars signaled the End of Days. SEE CHASIDISM; PHYSIOGNOMY.; RIGHTEOUS, THE.

Jacob of Marvege: Mystical diarist (Rhenish, ca. 13th century) who collected legal and spiritual answers about Jewish practice from the Angels by means of incubation and published them in a text, She‘lot u-teshuvot min ha-shamayim (“Questions and Answers from heaven”). These legal opinions were widely accepted, despite their paranormal origins. SEE DREAM.

Jashar, Book of: (Sefer ha-Yashar). “Book of the Upright.” A lost book of ancient Israel quoted only briefly a few times in Scripture, virtually nothing is known about its dimensions, content, or authorship. Based on the few quotes excerpted, the only useful thing that can be said is that it was probably poetic in genre. Based solely on its title, some Sages claim that it is the book of Genesis, but none of the quotes taken from the Book of Jashar appear anywhere in Genesis. There is a medieval mystical text by Abraham Abulafia and an early modern midrashic book by the same name.

Jehovah: Christian scribal misinterpretation produced this name for God from YHVH. The name has no religious significance to Jews. SEE EXPLICIT NAME OF GOD; TETRAGRAMMATON.

Jekon: One of the leaders of the fallen angel (I Enoch, 69:4-5).

Jephthah: A biblical Judge/Chieftain appearing in the book of Judges. As punishment for following through on his foolish vow to immolate his daughter (Judg. 11), God cursed Jephthah that his flesh should fall away bit by bit, so that no one spot would be his final burial place (Gen. R. 60:3).

Jerahmiel: (![]() ). “May God be Compassionate.” A destructive Angel who rules one of the compartments of Gehenna (MhG). In II Esdras, he is an archangel.

). “May God be Compassionate.” A destructive Angel who rules one of the compartments of Gehenna (MhG). In II Esdras, he is an archangel.

Jeremiah: The biblical accounts of the Prophet Jeremiah are effectively bereft of supernatural elements. The Rabbis have little else to report in this regard, other than a legend that the prophet was born circumcised (AdRN 2). He is satirized in Alef Beit Ben Sira as accidentally siring his own grandson. According to a medieval legend, he created a golem using Sefer Yetzirah (Sefer Gematriot).

Jerusalem: (![]() /Yerushalyim, also Ir David; Ir ha-Kodesh). The city, originally a Jesubite stronghold, became David's capital around 1000 BCE. He modestly renamed it the City of David, but its ancient name continues to overshadow all subsequent names given by it conquerors, including Aelia Capitolina by the Romans and Al Quds by the Arabs. Often it is simply referred to as “the Holy City.” It is the holiest of the four holy cities of Israel (Hebron, Tiberius, and Safed being the others).

/Yerushalyim, also Ir David; Ir ha-Kodesh). The city, originally a Jesubite stronghold, became David's capital around 1000 BCE. He modestly renamed it the City of David, but its ancient name continues to overshadow all subsequent names given by it conquerors, including Aelia Capitolina by the Romans and Al Quds by the Arabs. Often it is simply referred to as “the Holy City.” It is the holiest of the four holy cities of Israel (Hebron, Tiberius, and Safed being the others).

The creation of the world began at the point where Jerusalem now stands. Before the fall, Adam Kadmon made his offerings before God on a hilltop where one day the city and Temple would be built (Gen. R. 8:20). It is first mentioned in the book of Genesis as “Salem,” when the mysterious priest of the city, Melchizedek, visits Abraham (chapter 14). The Temple of YHVH is built there on Mount Zion by Solomon. The city has been destroyed twice, once by the Babylonians and once by the Romans, and conquered many times by different empires. Whenever it has been permitted by its rulers, Jews have lived in the city.

It is the location of many miracle s and regarded to be the nexus point between the material and all spiritual planes. There is a celestial Jerusalem (Yerushalyim shel Malah) that is the ideal counterpart of the earthly Jerusalem (Yerushalyim shel Mattah) (Tanh. Pekudei 1). In the celestial Jerusalem, the temple there continues to offer sacrifices to God, overseen by the angelic High Priest, Michael (Tan. 5a; Zohar III:15b, 68b, 147b). The earthly Jerusalem is also the center of the world (Tanh. Kedoshim 10).

Biblical Jerusalem was the epicenter of many fabulous phenomena. The entire city smelled like cinnamon (Shab. 63a). During the time the Temple stood, no woman ever miscarried, no one ever experienced demonic attack, there were never any accidents, the buildings never collapsed, the city was fireproof, no one was homeless, and no one was parsimonious (AdRN 35). As the “gate of heaven” (Gen. 28), all varieties of good and blessing flowed down from heaven through the city to benefit the world (Lev. R. 24:4). The Temple compound, as befits its unique metaphysical status, at times defied the laws of physics by providing infinite space for worshippers (Avot 5).

In the World to Come, the celestial Jerusalem will descend to Earth and the city will spread out in every direction to encompass all the returning exiles (Zech. 2-12; Ber. 49a; B.B. 75b, Sifrei 1). Messianic Jerusalem will be of astronomical proportions and unsurpassed splendor, encompassing thousands of gardens, pools, towers, and citadels, and only the righteous will be permitted entry. The gates and building will be made of precious gemstones, its walls of precious metals, and its glow will be visible to the ends of the earth (Isa. 54:12; Mid. Teh. 87:2; B.B. 75b; PdRK 299; BhM 3:74-75). Its towers will rise so high that it will merge with heaven (BhM 3:67; PdRK 466). God’s glory will reside there and experiencing it will become commonplace (Zech. 2).

A great tent will be made from the skin of Leviathan and all will gather under it to feast on its meat in a messianic banquet. The hidden vessels of the Second Temple will be recovered, the Temple will function again, and the waters of the abyss, now tamed, will issue forth from under the messianic Temple, growing into mighty streams that will freshen the waters of both the Dead Sea and the Mediterranean (Yoma 77b-78a; Zech. 14; Ezek. 47:1-12). clouds will convey the pilgrims of all nations to Jerusalem on a regular basis, where they will worship at the Temple in universal harmony.

Jesus: Itinerant Galilean holy man and, from a Jewish perspective, failed Messiah (ca. 1st century). In the Gospel accounts, Jesus is a miraculous figure, born of a mortal woman and the Holy Spirit. He has the power to heal, cast out demons, multiply foodstuffs, walk on water, and perform many other miracles. Christian dogma declares him the “only begotten son of God” and “God incarnate,” claims that Jews reject.

The Rabbis rarely mention Jesus or Christians in the centuries following his death. From the few unambiguous comments about him found in Talmud and Midrash, it is clear they knew very little about Jesus, and what little they did know came mostly from Christian sources. Often what appear in rabbinic literature are convoluted tidbits from the Gospel accounts. Thus a figure called Ben Stada—who may or may not be Jesus—gained magical skills as a result of spending his youth in Egypt (Shab. 104b). Whether or not the Shabbat passage is actually referring to Jesus, elsewhere it is clear some Rabbis believed Jesus was really a magician (Sanh. 104b). The medieval polemical tract Toldot Yeshu claimed that Jesus obtained his magical and miraculous powers by stealing the knowledge of the Tetragrammaton from inside the Temple. He wrote the name of God on parchment and inserted it into an incision (or a tattoo) in his skin. Jesus then used the power of God’s name to fly and to perform miraculous healings.

Jews were also highly skeptical of the Christian claim of his resurrection and ascension. Rather than ascending bodily into heaven as the Gospels claim, Toldot Yeshu asserts his Body was stolen by a gardener who used it for his own purposes. References to this “body theft” story also appear in Pagan and Christian apologetic literature about Jesus. Most of the more colorful Jewish legends appear in Toldot Yeshu.1

The Zohar is implacably, albeit cryptically, hostile to the figure of Jesus, and assigns him a variety of roles of impurity and evil in its metaphysics, most especially linking him with the demon Samael (I:146a; II:11a; 111a; III:124a).

1. Roth, Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 10, 10-14; vol. 15, 1208.

Jethro: The father-in-law of Moses. According to Midrash, for a time Jethro served as a sorcerer in the palace of Pharaoh. He saw Joseph use the rod of power the Patriarchs had inherited from Adam, so when Joseph died he took it and planted it in the garden of his home in Midian. There it remained, unmovable, until Moses appeared and drew the rod out of the earth. When he saw this, Jethro knew Moses was the man destined to deliver Israel, and he gave his daughter Zipporah to him in marriage (PdRE 40). In Zohar, his conversion to faith in the One God rectifies the sin of his ancestor, Cain (I: 28b; II: 67b).

Jewelry: SEE CROWN; EARS AND EARRING; GEMSTONES; RING; TZOHAR.

Jezebel: Queen of Israel through marriage to King Ahab. The Bible taught that she was a witch who used her powers to lead Ahab astray (2 Kings 9). She is one of “four women who ruled the world” (Es. R. 3:2).

Job: The Rabbis call him one of the “seven gentile Prophets.” In the pseudepigraphic Testament of Job, Job fights a protracted face-to-face contest with Satan. At the end of his life, Job gives his daughters miraculous belts that grant them power over Angels.

Jochnes and Mamres (alternately, Jannes and Mambres): The chief magicians of Pharaoh who battled Moses in Egypt (Ex. 7-8). They foresaw the coming of Moses by means of divination and so instructed Pharaoh to kill the Israelite firstborn sons. As the two sons of Balaam, they were true witches; they could fly and make themselves invisible (Gen. R. 86.15; Kid. 49b). Later they joined the Israelites in the Exodus as agent provocateurs and they were that “mixed multitude” that incited the people to construct the golden calf (Zohar II:191a-2: 191b). They also assisted Balaam in his efforts to curse Israel. Eventually they were slain using the power of the divine name (Men. 85a; Tanh. Ki Tissa 19; Yalkut Ex. 168). They derived their power from the Sefirah of Gevurah (Zohar I:83a, 249a-b; Zohar II:28a).

Joel: (![]() ). An Angel mentioned in the Testament of Solomon.

). An Angel mentioned in the Testament of Solomon.

Jonathan, Rabbi: SEE YOCHANAN.

Jonathan Shada: A demon mentioned in the Talmud (Yev. 22a).

Joseph: Patriarch and son of Jacob. Joseph was a celebrated oneiromancer, with a special God-given capacity to interpret dreams. On three occasions he demonstrates this talent in the Bible (Gen. 37, 39, 41). He was also a diviner, engaging in the practice of hydromancy by use of a ritual cup. This cup becomes the occasion for one episode in the reconciliation of Joseph and his brothers (Gen. 43-44).

According to the Midrash, the pit his brothers cast him into was populated by poisonous snakes and scorpions, but like Daniel, he was miraculously protected (Shab. 22a; Gen. R. 84:16). Later, Gabriel taught Joseph all the world’s languages while he languished in prison. After his death, the Egyptians had his Body sealed in a metal coffin and sunk in the Nile in order that his bones would bless the river (MdRI BaShallach; Ex. R. 20:17).With the help of Serach bat Asher, Moses was able to raise the coffin from the deep in order to fulfill the promise made to Joseph, on his death bed, that his bones would be buried at Machpelah (Sot. 13a-b; MdRI BeShallach; PdRK 11:12). Probably the most enduring legend about Joseph is that the descendants of Joseph are immune to the evil eye:

R. Yochanan [who was surpassingly handsome, like his ancestor Joseph] used to go and sit at the gates of the mikvah. When the daughters of Israel ascend from the bath, said he, “Let them look on me, that they may bear sons as beautiful and as learned as I.” Said the Rabbis to him: “Do you not fear an evil eye?” “I am of the seed of Joseph,” he replied, “against whom an evil eye is powerless.” For it is written, Joseph is a fruitful bough, a fruitful bough by a (Alay ayin) fountain, (Gen. 49:22) about which R. Abbahu observed: Read not “alay ayin [by a fountain]” but “oleh ayin [transcends the eye].” R. Jose b. Hanina said: [It is derived] from this passage, And let them grow [ve-yidgu] like fish in the midst of the earth, into a teeming multitude in the midst of the earth [Gen. 48:16; Jacob’s blessing of Ephraim and Menasheh, the two sons of Joseph]; Just as fish in the seas are covered by water and the eye has no power over them, so also are the seed of Joseph: the eye has no power over them. (Ber. 20a)

Joseph ben Ephraim Caro: SEE CARO, JOSEPH; MAGGID.

Joshua: The successor of Moses as leader of the Israelites, Joshua meets an Angel outside of Jericho, the commander (Sar) of the host of heaven, which later tradition identified with Michael (Josh. 5:13). He commanded the sun to stand still for thirty-six hours (Yalkut Lech Lecha). Joshua eventually married Rehab, and the Prophets Jeremiah and Huldah were their descendants (Num. R. 8; MdRI Yitro).

Joshua ben Levi: Talmudic Sage (ca. 3rd century). In addition to being a prodigy in Jewish law, Ben Levi was also one of the most colorful adepts of esoteric knowledge in rabbinic literature. He was a confidant of the angelic Elijah. Elijah was Joshua’s maggid, or spirit guide (Sanh. 98a). Joshua accompanied Elijah on some of his earthly missions (Mak. 11a; Gen. R. 35:2; BhM 2).

Rabbi Joshua is most famous for having toured the seven levels of Gehenna and the seven heavens. There are multiple versions of his visions in both rabbinic and medieval texts. In one case, it is told that he first tricked the Angel of Death into giving up its sword before Joshua jumped over the wall to Eden:

When he (ben Levi) was about to die, the Angel of Death was instructed, “Go carry out his wish.” [The origins of the Make a Wish Foundation?] When he (the Angel) showed himself to him, [ben Levi] said, “Show me my place [in paradise].” “Very well,” he replied. [ben Levi] Said “And give me your sword, or you may frighten me on the way.” He gave it to him. On arrival, he lifted him up [over the wall] and showed him [paradise]. [ben Levi] Jumped and dropped on the other side. The Angel grabbed him by the cloak, but he exclaimed, “I swear I will not go back!” …”Return my sword!” He [the Angel] said, but he would not. A Bat Kol [a heavenly echo] finally went forth and said to him, “Return the thing to him, for it is required for mortals” [and he returned it]. (Ket. 77b)

In one of the alternate versions of this tale, he returned the weapon only after extracting a promise from the Angel that it would henceforth no longer display the fearful weapon to his victims (Ber. 51a; Eruv. 19a; BhM 2, 5).

Joshua had the power to make it rain (J. Tan. 3:4). He also practiced oneiromancy and taught methods for interpreting and averting ill omens that appear in dreams (Ber. 56b). He provided sage advice on how to avoid attracting the Angel of Death (do not take a shirt directly from someone’s hand in the morning, do not allow someone who has not washed their hands to wash yours, and don’t stand close to a woman who has just returned from caring for a corpse) (Ber. 51a). He also understood how to interpret omens Berachot 7a.

His son Joseph also had the power to see visions (Pes. 50a; B.B. 10b).

Joshua ben Perachia: Early Sage (ca. 1st century BCE- 1st century CE). He was one of the zugot, the scholars who formed the leadership of the Jewish community in the third through first centuries BCE. He is credited as being a teacher of Jesus while he lived in exile in Egypt (Sanh. 107b). Evidently, there is a legend (this writer cannot identify the source) that Joshua once used a get to exorcise a succubus . For this reason, his name will sometimes be invoked in the text of amulets and incantation bowls that likewise use the language of divorce to exorcise Liliths and female demons, as seen in this example:

This day above any day, and generations of the world, I Komesh bat Machlaphta have divorced, separated, dismissed thee, O Lilith, Lilith of the desert, hag and ghul … I have fenced you out by the ban which Joshua ben Perachia sent against you. 1

1. R. Patai, “Exorcism and Xenoglossia among the Safed Mystics,” The Journal of American Folklore 91, no. 361 (1978): 225; Naveh and Shaked, Amulets and Magic Bowls, 17, 159-61.

Joy and Humor: “Serve God in Joy” (Ps. 100:3). Judaism emphasizes that joy and laughter are spiritual tools that draw one close to God (Avot 4:1; Shab. 30b; Ben Porat Yosef 49a). Humor, music, and dance are, in fact, forms of worship. Chasidism in particular teaches the need to make joy central to worship, and offers techniques for cultivating joyfulness on a daily basis. Sadness is a kind of Satan, a spiritual obstacle to be overcome daily (Zohar I:180b).

Despite the assumptions of dour puritans of all faiths, both the Bible and rabbinic literature brim with humor: puns, wordplays, joke names, and even episodes of Schadenfreude. The entire biblical Book of Esther is written in the style of a farce about a very serious subject, anti-Semitism, and through the celebration of Purim, Jewish tradition treats it as an elaborate parody.

Two jesters are mentioned in the Talmud as spiritual agents of God (Tan. 22a). The Baal Shem Tov particularly praised the work of clowns in opening people’s hearts to God. Chasidic masters employed witty stories, jokes, and even outright pranks in order to instruct their disciples, a custom still markedly evident in rabbinic sermons to this day.

Jubilees, Book of: This retelling of the events of Genesis is a Sefer Chitzon, a book “outside” the biblical canon. It features the story of the fallen angel, the giants, and a sectarian solar calendar. Multiple copies of it were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the priests of Qumran may well have been the advocates, or even the authors, of the Jubilees ideology.

Judah: Patriarch and son of Jacob, progenitor of the tribe of Judah and therefore of most Jews. His voice was so powerful it could be heard in neighboring countries. He was reported to have fantastic strength, superior to Samson. He could grind an iron bar to dust with his teeth, and become so angry the hair over his heart would burst out, tearing his garment (Gen. R. 91-93:7). The “Angel of Desire” drove him to have sex with Tamar (Gen. R. 85). He completed the restoration, begun by his grandfather Abraham, of the presence of the Shekhinah in the world. The Shekhinah granted him eternal kingship in return (Zohar III:237b).

Judah ben Samuel he-Chasid or Judah the Pious: Founding figure of the German Pietist movement and wunder-rabbi (German, ca. 12th-13th century). His birth was miraculously portended, and his future greatness was revealed through a divination ritual by his father. He himself could foretell the future of individuals. He could use the name of God to constructive ends, from healing the sick to capturing criminals and curbing dangerous bishops. A number of his segulot have been preserved. He could teleport via a cloud. He believed that one could learn new insights into the Torah and its interpretations by consulting Angels, adjuring demons, and using the theurgic power of certain Jewish Prayers, especially the sh’ma (Or Zarua, Eruv. 147; Meirat Einayim). In at least one account, he conjured a dead spirit (Ma’aseh Buch; Sefer ha-Gan). When he became convinced by divination that a woman’s barrenness was a lifelong condition, he had the woman undergo a simulated burial and resurrection in order to cure her. His major works were Sefer ha-Kavod (which has not survived intact), Sefer Chasidim, and Sod ha-Yichud.

Judah Loew ben Bezalel (the Maharal): Rabbi, polymath, and mystic (Czech, ca. 16th century). A great communal leader of the Jews of Prague, Rabbi Judah is most famous for the story of the golem he created to protect the community against anti-Semitic violence (Miflaot Maharal).

Judgment: (![]() /Mishpat; qdx/Tzedek). God is the source and guarantor of justice (Ps. 82). In Genesis, chapter 18, Abraham asks the rhetorical question, “Will not the Judge of all the earth deal justly?” Since, as the book of Job highlights, there is in fact no assurance of justice being meted out in this world, Judaism teaches God’s ultimate judgment awaits us in the World to Come. In the rabbinic understanding, post-mortem judgment comes in three phases: chibbut ha-kever, Gehenna, and Yom ha-Din (the torments of the grave, hell, and Judgment Day). The process each soul faces is based on the moral condition of the person; whether he or she is counted among the righteous, the wicked, or the Beinonim, the “in-betweens” whose life is a mix of sin and merit. Kabbalists divide the afterlife into seven periods of judgment (Zohar III:127a).

/Mishpat; qdx/Tzedek). God is the source and guarantor of justice (Ps. 82). In Genesis, chapter 18, Abraham asks the rhetorical question, “Will not the Judge of all the earth deal justly?” Since, as the book of Job highlights, there is in fact no assurance of justice being meted out in this world, Judaism teaches God’s ultimate judgment awaits us in the World to Come. In the rabbinic understanding, post-mortem judgment comes in three phases: chibbut ha-kever, Gehenna, and Yom ha-Din (the torments of the grave, hell, and Judgment Day). The process each soul faces is based on the moral condition of the person; whether he or she is counted among the righteous, the wicked, or the Beinonim, the “in-betweens” whose life is a mix of sin and merit. Kabbalists divide the afterlife into seven periods of judgment (Zohar III:127a).

Dying itself is seen as a kind of atonement for one’s sins (M. Sanh. 6:2) and the terror of encountering the Angel of Death begins it all. This is the start of the chibbut ha-kever, and the subsequent separation of the soul from the Body is overseen by various angels of judgment, especially Domah, the angel of the grave. The newly deceased souls, lingering at the grave, must review their earthly deeds and experience the disintegration of their earthly remains (Lev. R. 4; Sanh. 47b; Tan. 11a; Mid. Teh. 11:6; Chag. 5a). The righteous, by contrast, are spared both the pain of death and the confrontation with the grimmest angels (PR 44:8). Those who gave charity in secret or were diligent in their Torah study will also be spared the worst of this first phase (PR 2; Ket. 104a).

The second, intermediate phase of the rabbinic scheme involves the placement of the soul pending the final Day of Judgment. The souls of the righteous, as well as those who underwent enormous suffering while still in their bodies (Eruv. 41b), go directly to Gan Eden or the Treasury of Souls beneath the Throne of Glory. The wicked and the Beinonim descend into Gehenna, where they are assigned to different compartments. For the Beinonim (that is, the bulk of humanity), Gehenna is a kind of purgatory, purifying their souls of the accreted sins of their lifetime. The process lasts a maximum of twelve months, after which the souls are transferred to Gan Eden to await the Day of Judgment (Shab. 33b; R.H. 17a; Ex. R. 7:4). For the wholly wicked, Gehenna is where they will remain until the End of Days. Some Sages in the Talmud try to identify those who will meet such an awful judgment. They include those who utterly deride the teachings of God and who combine adultery with publicly shaming and slandering their neighbors as those they think deserve the fate of “going down into Gehenna and not coming up.” (B.M. 58b). Others add the entire generation of the Flood (M. Sanh. 10:3).

Third, at the Final Judgment at the End of Days, all souls undergo resurrection and must stand before God, the Judge of Judges (Sanh. 91a). Most souls, even those who were burdened with so many sins that they had to be summoned directly from Gehenna, will then know the final reward of the World to Come. Only the utterly and completely wicked will be annihilated and blotted out completely from under heaven and from all memory (B.B. 11a; Ber. 18b; Shab. 152b-156b). SEE DEATH; ETERNAL LIFE; JUDGMENT, DAY OF; WORLD TO COME.

Judgment, Day of: (![]() /Yom ha-Din; Yom Adonai; Yom ha-Hu; Ait ha-Hee). A term often applied to the annual observance of Rosh Hashanah, when God judges Creation (even the Angels are judged—Isa. 24:21; High Holiday Machzor) or to the later tradition that there are actually four days of judgment each year: Rosh Hashanah, Sukkot, Passover, and Shavuot (PdRK 7:2).

/Yom ha-Din; Yom Adonai; Yom ha-Hu; Ait ha-Hee). A term often applied to the annual observance of Rosh Hashanah, when God judges Creation (even the Angels are judged—Isa. 24:21; High Holiday Machzor) or to the later tradition that there are actually four days of judgment each year: Rosh Hashanah, Sukkot, Passover, and Shavuot (PdRK 7:2).

“Judgment Day” is also used to refer to the eschatological moment at the end of time when the sleeping dead are resurrected to give a final account for their deeds in life. Many versions of this day appear in Jewish writings, starting with the biblical book of Daniel (chapter 7). Some describe it as a day of darkness and wrath when all the nations will be judged (Am. 5, 8; Isa. 1-3). It will be marked by earthquakes and consuming fires. Those who go through it will be purified, like silver in a crucible (Zech. 14). Even as individuals are called to moral account, the nations will also be judged. The nation of Israel will be vindicated, and its suffering at the hands of other nations redressed. The righteous among the nations will be accounted to Israel, and will ascend God’s sacred mountain to form the messianic Kingdom of God. Some traditions link the day to the coming of the Messiah, though others distinguish the two events from each other to varying degrees (R.H. 16b-17b). SEE BEINONIM; EDEN, GARDEN OF; ESCHATOLOGY; ETERNAL LIFE; GEHENNA.; JUDGMENT