50 Famous Firearms You've Got to Own: Rick Hacker's Bucket List of Guns (2015)

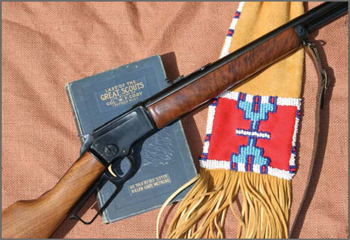

MARLIN MODEL 39

The Model 39 is basically the same rifle Annie Oakley used in her trick shooting act with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West shows, around the turn of the last century.

Everyone enjoys meeting a celebrity, and when you pick up a Marlin Model 39, you are holding the oldest continuously produced rifle in firearms history. In a way, you are also connecting with Annie Oakley, one of the world’s greatest trick shooters, and a woman who was dubbed “Little Sure Shot” by Chief Sitting Bull, when they were both appearing in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West shows around the turn of the last century. The diminutive shooter—she was only five-feet tall—repeatedly wowed audiences with her expertise at hitting targets with a Marlin 1897, the immediate predecessor to the Model 39.

Indeed, one cannot write about the Model 39 without bringing in the Model 97, the first repeater that could digest .22 Shorts, Longs, and Long Rifle cartridges interchangeably. The slim, lightweight lever-action also featured Marlin’s new (at the time) takedown feature, which not only made for easy transportation, but also enabled shooters to clean the gun from the breech. To disassemble, all one had to do was cock the hammer, unscrew the large retaining screw on the right side of the receiver, and carefully lift the buttstock portion up to the right of the frame. The breech bolt then slides back, up, and out, as a separate piece from the action.

In 1922, after a brief manufacturing hiatus caused by World War I and a change in company ownership, the Model 1897 was brought back, only this time it carried a new designation as the Model 39. In all other respects, the new pistol-gripped .22 was nearly identical to the older Model 97, complete with casehardened receiver, octagon barrel, and its trademark .22 rimfire cartridge interchangeably and takedown features. Of course, being a Marlin lever-action, it also boasted a solid top receiver and side ejection, just like the Model 97, although the new Model 39 loaded via a button-type magazine tube under the barrel, rather than the latch-type tube of the Model 97. Otherwise, this was basically the same gun as its predecessor. Initial cost was $26.50, which made the Marlin 39 one of the most expensive .22 rifles on the market. But quoting from Marlin’s 1922 catalog:

The Marlin Model No. 39 lever action rifle is the most accurate .22 repeating rifle in the world, and is the choice of expert shooters for hunting small game such as rabbits, squirrels, crows, foxes, etc., and for target shooting up to 200 yards ... a great many big-game hunters prefer this lever action rifle, as it has the “feel” of a big game rifle and permits them to keep in practice at small expense.

Claims of 200-yard target accuracy and big-game rifle “feel” might have been a bit of a stretch for the slim, 51⁄2-pound .22, but there was no denying that it could consistently pop tin cans at 100 yards and was fast handling enough for effective running shots at jackrabbits. For thousands of admirers, it seemed there was little that could be done to improve the Model 39. Nevertheless, somewhere around the early 1930s, the bolt was strengthened to permit use of the new, high-speed .22 ammo that was just coming onto the market. A retaining screw was also added to keep the internal frame-mounted ejector from hanging up on patches as the cleaning rod was pushed through the bore. (One thing to know with this model is that, if the ejector wasn’t freed before reassembling the rifle, the gun would fail to eject.)

The author’s Model 39 TD (Take-Down) carbine, which is no longer in the Marlin line, featured a straight-grip stock and 161⁄4-inch barrel.

The current Model 39’s takedown feature began with the original Model 1897.

Although the Model 39 had neared mechanical perfection as the world’s only lever-action .22, in 1939, it was reintroduced as the Model 39A. The changes were merely cosmetic. Gone was the old, octagon barrel, replaced by a round, semi-heavy barrel with Ballard-type rifling. The ivory bead front sight had been changed to a silver bead, but the tang was still drilled and tapped for a peep sight. More notable changes came a year later, when the slim stocks of the previous 1897 and Model 39 rifles were updated to a more hand-filling semi-beavertail forearm and a slightly thicker pistol grip buttstock.

In 1945, after a break in production prompted by WWII, the Model 39A returned, only this time with a ramped front sight and a blued receiver, which replaced the pre-war case hardened receiver. This is essentially the same rifle that remains in the Marlin line today, although, over the years, a number of minor variations have been made. The most notable was the 39A Mountie, a handsome, straight-stocked, 20-inch-barreled carbine that came out in 1953. In addition, the lever contour had been changed from square to round, and, in 1988, a cross-bolt safety and rebounding hammer was added, much to the chagrin of many who learned gun safety with the little .22 on half-cock.

Although Marlin did not normally offer custom options on its Model 39, a few notable exceptions exist. One I am personally familiar with is a pair of factory nickel-plated Model 39s that have a lasso-twirling cowgirl expertly relief-carved into the premium grade stocks. These guns were presented to the late Gail Davis, the actress (and expert trick shot) who played Annie Oakley on TV, from 1953 to 1956. In addition, Marlin has produced a number of commemorative models, including the 39ADL, a deluxe version manufactured in 1961, a Model 39 Article II, in 1971 (which paid tribute to the NRA’s 100 years of dedication to America’s gun owners), and, appropriately, an 1897 Annie Oakley Commemorative, in 1997.

My experience with the Model 39 goes back to the introduction of the Mountie, although, at the time, I was too young to harbor any realistic hopes of acquiring one. In the 1980s, I finally bought a used 39M and made the mistake of packing it as an extra camp gun on a big-game hunting trip. My guide couldn’t take his eyes off that Marlin .22 from the minute I took the two halves from my bedroll. Later, when I “barked” a squirrel with that Model 39 (I was actually trying for a head shot and missed, but the effects were just as impressive to the guide, and who was I to tell him differently?), he offered me a ridiculous price for the little gun. I refused. After our hunt, the guide again approached me, this time with a wad of cash that far superseded his previous offer.

“I’ve got to have that rifle,” he pleaded. “It’s the best shootin’ .22 I’ve ever seen.”

I finally succumbed to temptation and have regretted it ever since. A few years later, right before the advent of the cross-bolt “safety,” I did a shooting test with a then-current Marlin 39 TD (Take-Down) carbine, which featured a straight-grip stock and 161⁄4-inch barrel. The accuracy with copper plated bullets was so impressive (soft lead bullets tend to clog microgroove rifling), I bought the gun.

To date the Marlin 39 still remains in the line, with more than 2,200,000 having been produced—but, sadly, its days might be numbered. It is an expensive gun to manufacture (continuing its reputation as one of the most expensive .22s around), and other lever-action .22s now exist. But I’ve still got my 1980’s Model 39. Needless to say, I’m hanging on to this one as a permanent part of my bucket list.