50 Famous Firearms You've Got to Own: Rick Hacker's Bucket List of Guns (2015)

RUGER

BLACKHAWK .357 AND .44 MAGNUM FLAT TOPS

Back in 1955, William Batterman Ruger’s fledging Sturm Ruger & Company was already batting two for two, first in 1949 with its Mark 1 Standard Pistol and then, in 1953, with the Single Six—a seven-eighths scale, vastly improved .22 version of the Colt Single Action Army. Both rimfires had hit the ball out of the park, but now the TV Western craze and fast-draw mania were starting to sweep the country. As a result, outdoorsmen, weekend plinkers, and would-be gunslingers were all clamoring for a big-bore single-action.

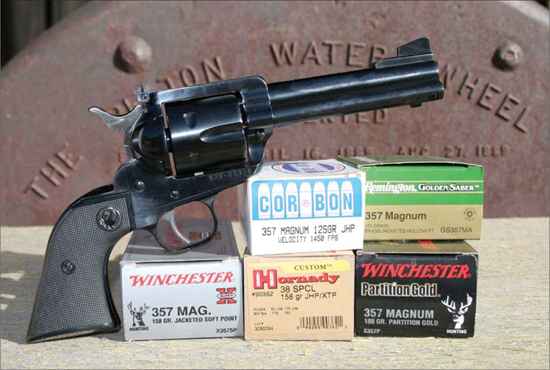

Ruger’s New Model .44 Magnum Blackhawk.

At the time, the only options were used, first generation Peacemakers and a Great Western replica marketed by Hy Hunter of Burbank, California (although, contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t made by him). Consequently, Colt’s was planning to relaunch its Single Action Army, the sixgun they had declared obsolete back in 1947. But times had changed, and this was literally a whole new ball game.

For Bill Ruger, his next offering to the shooting public was obvious, especially in light of rumors that Colt’s was planning to reenter the single-action arena: he would develop a full-sized single-action chambered for the powerful .357 Magnum, at the time the most popular pistol cartridge in America. Of course, Colt’s had produced a scant 525 pre-war Peacemakers in .357 Magnum, but the sixgun Bill Ruger created was nothing like any single-action that had come before it.

For one thing, the frame was 4140 chrome molybdenum steel. Rather than Colt’s costly case hardening, Ruger anodized the frame black, a technique he also used on the one-piece cast aluminum trigger guard and backstrap assembly, a carryover borrowed from the Single Six. This made the gun much more economical to produce, though at the same time, Ruger incurred the extra costs of also using chrome molybdenum steel for the hammer, loading gate, trigger, and pawl, even though he admitted these parts didn’t require this added strength. Still, Ruger felt it added to the gun’s prestige.

Because of the .357 Magnum’s higher pressures, Ruger decided to dramatically beef up the topstrap. That extra-thick bar of steel created the ideal platform to add a Micro click-adjustable rear sight, which was teamed with a Baughman-style ramp front sight having an 1⁄8-inch wide serrated steel blade. This was a vast improvement over the shallow topstrap groove and high front blade of the SAA, which caused the Peacemaker to shoot low. Also, Ruger opted for a spring-loaded, frame-mounted firing pin, another carryover from the Single Six. He also eschewed the flat mainspring of the SAA for a practically unbreakable coil spring. Likewise, the flat trigger bolt spring, always subject to breaking, was replaced with music wire coil springs. Finally, to solve the Model P’s habit of “shooting loose,” Ruger incorporated Nylok screws.

The author’s finely tuned .44 Magnum Super Blackhawk, as customized by Bill Oglesby, of Oglesby & Oglesby.

To ensure this redesigned single-action would not be misconstrued as a reworked Colt, such as those customized by pioneering firms like Christy Gun Works and King Gunsight Company, its name would have to convey the fact that it was an entirely new gun. In keeping with his passion for classic motorcars, Bill Ruger christened his new revolver the Blackhawk, after the famous Stutz roadster of the 1920s. (Three years later, Ruger would again turn to the Stutz Motor Car Company for inspiration, when he named a diminutive .22 revolver the Bearcat.)

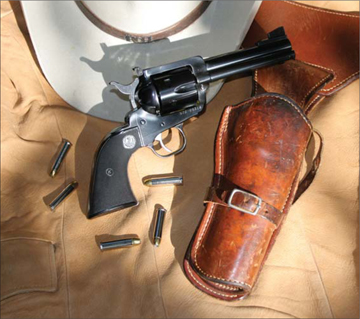

With its black, checkered, two-piece Butapreme grips (changed to two-piece walnut, in 1960), thick frame, and 45⁄8-inch barrel, the Ruger Blackhawk was a stylish, albeit somewhat chucky-looking handgun. Although it didn’t balance as well as the Single Action Army, the Blackhawk weighed the same, two pounds and six ounces, thanks to its aluminum backstrap/trigger guard assembly and ejector tube. Because of its thick, squared-off topstrap, these early Blackhawks have since been nicknamed “Flat Tops,” by collectors.

Although I was wasn’t even a teenager at the time, I still remember staring in fascination at Ruger’s first magazine ad announcing the new Blackhawk in the August 1955 issue of the American Rifleman. “The ultimate development of the single-action revolver,” the copy proclaimed. This was the same year Colt’s reintroduced its Peacemaker, but it was only available in .45 Colt and .38 Special. Ruger had the single-action .357 Magnum field to itself. What’s more, the Blackhawk listed for $87.50, compared to $125 for the Colt SAA.

Hunters were quick to embrace the new Blackhawk, but it also found acceptance with those engaged in fast-draw, the fastest growing sport in the country. With its smooth action, the gun didn’t need tuning, although snipping a coil or two off the mainspring lightened the hammer pull. Most competitors replaced the Micro rear sight with a steel blank, so they wouldn’t rip off their thumbs when fast-cocking the gun. Many also removed the front sight, so it wouldn’t drag on the holster when they cleared leather. (It should be noted all fast-draw contests were conducted only with blank ammunition or wax bullets—live rounds were never used, a common-sense safety rule that is still followed.) Like Cowboy Action Shooting today, hours of hard and fast hammer cocking put a lot of wear and tear on those Ruger Flat Tops, but the guns proved to be practically indestructible. It got to a point where Colt’s finally stopped sponsoring the Sahara Las Vegas National Fast Draw Championships, as most events were being won by Ruger Flat Tops.

In 1962, with serial No. 42,670, the era of the Flat Top came to an end, as the topstrap was recontoured that year to incorporate protective “ears” on either side of the rear sight. By that time, Ruger had retooled the original Blackhawk design, beefing it up slightly to handle the then-new .44 Magnum cartridge. However, with its standard-sized XR-3 plow-handled grips—the same size used on the .357 Magnum—the gun was almost uncontrollable with full-power factory loads, and many shooters resorted to firing .44 Specials out of it. The .44 Magnum Blackhawk morphed into the Super Blackhawk in 1959, with a 71⁄2-inch barrel (although a few rare 61⁄2-inch barreled guns were also produced). Even more dramatically, the Super Blackhawk featured a non-fluted cylinder, elongated walnut grips, and a Dragoon-styled square-back trigger guard.

Externally, this New Model .357 Flat Top Commemorative mirrors the original 1955 version.

A rare factory engraved New Model .357 Anniversary commemorative.

The next significant change came about, in 1973, when Ruger revamped its entire single-action lineup to incorporate a revolutionary new transfer bar safety which, for the first time, permitted a single-action revolver to be safety carried with six rounds in the cylinder. To load these New Models, as they have subsequently been called, the loading gate was flipped open, which freed the cylinder and allowed it to rotate for loading. That eliminated the half-cock notch on the hammer, a characteristic that still trips me up after so many decades of shooting a Colt single-action. Muscle memory occasionally causes me to attempt to put a New Model Ruger SA on half-cock, which, of course, no longer exists.

The New Model Super Blackhawk gradually morphed into a sixgun sporting a more rounded trigger guard and a less elongated grip frame. However, I found myself wishing the Super Blackhawk also sported a shorter 45⁄8-inch tube, like the original Blackhawk in .357 Magnum. It would be the perfect backup gun, I theorized, for a safari to Africa. In 1985, I expressed this thought to the late Tom Ruger, who was Sturm, Ruger’s Vice President of Marketing. A gun was subsequently produced for me, and the shorter barrel has now become a regular part of Ruger’s lineup. In recent years, I had this gun extensively reworked and customized by Bill Oglesby of the gunsmithing firm Oglesby & Oglesby, a job that included case hardening the frame, fine-tuning the action, and outfitting it with Oglesby’s patented, one-piece faux ivory Gunfighter grips.

It was the original .357 and .44 Magnum Flat Tops that established a new criteria for every big-bore single-action that came after it. Small wonder that, in 2005, in honor of the .357 Magnum Flat Top’s fiftieth anniversary, and again in 2006 to acknowledge the fiftieth anniversary of their .44 Magnum Flat Top, Ruger issued limited editions (with New Model improvements) of its first bold ventures into the big-bore single-action arena. Whether original Old Models or reissued New Models, both versions have a definite place on our bucket list. Just don’t try putting the New Models on half-cock.