50 Famous Firearms You've Got to Own: Rick Hacker's Bucket List of Guns (2015)

WINCHESTER MODEL 94

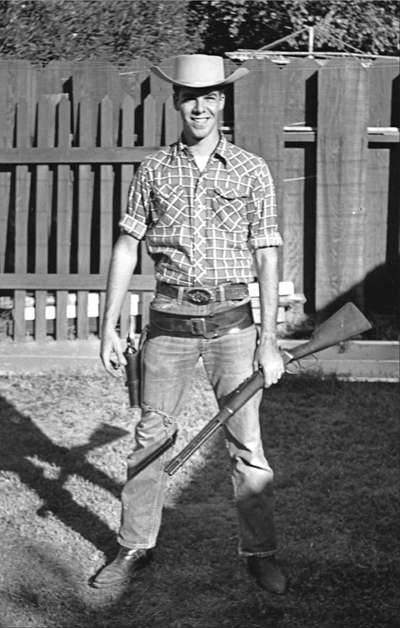

This hand-colored photo, taken in the early 1900s, shows a transplanted Pennsylvanian who ventured to the Pacific Northwest and became an adept hunter and guide. He is shown proudly carrying his Model 94 carbine and meat for the table.

I have a special affinity for this classic deer gun, because it was the first big-bore rifle I bought. However, I initially viewed it not as wood and steel, but as a black-and-white line drawing in one of the chapters of the late Harold F. Williamson book Winchester—The Gun That Won The West.

I remember, as a kid, pouring over that book—which I still own and is now torn and tattered—and studying every line of that illustration of the Winchester Model 1894 carbine: its square-shouldered receiver, the noticeably large trigger guard (especially when compared with those of the earlier Winchester saddle carbines), and the graceful, complementary taper of the barrel, magazine tube, and walnut forearm.

Of course, back then, I was too young to purchase, let alone afford, a Model 94 carbine. But one day that moment came. I remember it distinctly. It was at the old Pinney & Robinson’s Sporting Goods store in the Park Central Shopping Center in Phoenix, Arizona. I had walked in to browse the gun racks, as I often did, and there it was, a slightly used, flat-band Model 94 carbine in the coveted .30-30 caliber, which everyone knew was the deer cartridge. If you want to go after black bear, the old-timers told you, you bought a 94 in .32 Winchester Special, but, if it was venison you wanted for the table, then only a .30-30 would do.

Of course, the reality is that both cartridges are practically identical, ballistically speaking, and the only reason the .32 Special was developed in 1895—the same year the .30-30 was introduced as America’s first smokeless powder round—was that unlike the faster 1:12 rifling of the .30 WCF, the slower 1:16 twist of the .32 Special was more suited to stabilizing the bullet when reloading that cartridge with blackpowder, obviously to appeal to those hunters back then who didn’t trust a cartridge whose smoke they couldn’t see.

Needless to say, I was mesmerized by that 94 flat band (a unique post-war feature of Model 94 carbines produced from April 1946 through December 1948) in Pinney & Robinson’s used gun rack. To make it even more tantalizing, the carbine came with a saddle scabbard stamped “Marfa, Texas.” The rancher who had previously owned that Model 94 had brought it in to Pinney & Robinson’s to trade for a “modern” bolt-action rifle. I was glad he had, and often thought it would have been interesting to meet him after the fact.

As I recall, the asking price for gun and leather was $50, and I ended up trading a .22 Springfield Model 87A semi-automatic rifle and $30 cash for the 94 and scabbard; although I have acquired numerous Winchester 94s since, I still have that scabbard. Later that year after acquiring that first rifle, I took my first mulie with it, thus perpetuating the Model 94s reputation of having taken more deer than any other rifle in America. To be sure, the Model 94 and the .30-30 cartridge were so indelibly intertwined that the gun was often simply referred to as a “thuty-thuty,” no matter what its caliber when I was growing up in Arizona. In fact, for a long time I was under the impression that all pickup trucks came with a rifle rack and a .30-caliber Model 94 carbine in the cab’s rear window.

The author, with a wild boar taken by him with a single shot from a Model 94 carbine made in the early 1940s.

Like many other great guns of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Model 1894 came from the fertile mind of inventor John Moses Browning. It was the culmination of all the tubular magazine lever-actions that had come before it—including the Browning-designed Winchester Models 1892 and 1886. Moreover, the Model 94 was the first repeating rifle to be adapted to smokeless powder cartridges, specifically the .25-35 and the .30 WCF, which, of course, came to be known as the .30-30. Winchester Repeating Firearms paid Browning $15,000—the same amount he had previously received for his Model 1886 and 1892 patents—for rights to manufacture the Model 94.

The new gun quickly earned a reputation as a hard-hitting, close-range hunting rifle. These attributes were primarily due to its smokeless powder chamberings and an action that, while not quite as smooth as in the Models 1873 and 1892 (both of which were still in the line at the time), was one that was noticeably stronger. A single, solid steel rod slid up and locked behind the closed bolt, thus providing greater safety to the shooter, a solid selling point in those transition years between blackpowder and smokeless. Also unique to the Model 94 was its hinged floor plate that pivoted down when the action was opened. Of course, the rifle’s nickel steel barrel was a big feature, even though initial metallurgy problems kept the two new smokeless powder chamberings from appearing until 1895. Thus, ironically, the first smokeless powder repeater was initially available only for two older blackpowder rounds, the .32-40 and the .38-55. It wasn’t until a year later that the Model 94 came out in the much-touted .25-35 and .30 WCF chamberings.

Although this High Grade Oliver F. Winchester Limited Edition, the first “new” Model 94 to be produced by Miruko of Japan in 2010, was intended to be a collectable, the author could not resist the temptation to see how it shot. It is shown with the cartridge that helped make the Model 94 famous, the .30-30.

Rifles with 26-inch round or octagon barrels were standard, as was a 20-inch barreled saddle ring carbine, which proved to be extremely popular, especially in its .30-30 chambering, as the same sight picture could be used out to 125 yards and still result in a lethal hit on deer-sized targets. Small wonder the Model 94 quickly became a favored firearm not only for hunters, but also as a working tool on ranches and farms. And, because the large trigger guard could readily accommodate gloved hands, it was the rifle and carbine of choice during the 1897 Alaskan Gold Rush, resulting in the Winchester 94 being christened “The Klondike Model” during its earliest years.

Gold seekers and cowboys weren’t the only fans. Law enforcement agencies, including the Los Angeles and Glendale California Police Departments, various railroad police, and such diverse organizations as the Texas Rangers and New York State Troopers added the Winchester 94 to their gun racks. During World Wars I and II, approximately 1,800 special ordnance-marked Model 94 carbines were issued to U.S. troops stationed along the Mexican and Canadian borders, as well as to Home Guard units and members of the Army Signal Corps, which, according to noted author Bruce N. Canfield in his book U.S. Infantry Weapons of The First World War (Andrew Mowbray Publishing), used them to guard our spruce forests from enemy saboteurs, as, in those days, Sitka spruce was one of the primary materials used for airplane construction.

Besides rifles and carbines, special order Model 94s were produced up through the first half of the twentieth century. Options included half-round/half-octagon barrels, takedown versions, special engraving and checkering patterns, and a variety of barrel lengths, including rare Baby Carbines (since dubbed “Trappers” by collectors) that sported 14-, 15-, and 16-inch barrels.

Over the years, a number of changes have taken place with the Model 94. In 1924, the rifle was discontinued and in 1951 the longer wood of the carbine’s forearm was shortened. In 1964, in what is now recognized as an ill-advised move, manufacturing procedures were modified to reduce costs. Thankfully, by 1967 the company realized it had done something terribly wrong and steps were gradually taken to restore the Model 94 to its former glory. Nevertheless, that chapter in the Model 94s history has provided collectors with the designations of “pre-’64” and “post-’64” Winchesters, with pre-’64 guns commanding more money on the collectors’ market.

The author, in his teenage years in Arizona, proudly poses with his first Winchester 94 carbine, a flat band .30-30.

In 1981 “Side Eject” was added, so that for the first time, it became easier to mount a scope on the Model 94, for those who favor such things on an otherwise handsome carbine. In the 1990s the traditional half-cock was removed and replaced by a trigger-block safety and a trigger return spring, along with an ugly dished-out push-button safety that, thankfully, was removed, in 2003 and replaced by a tang-mounted safety. However, those traditionalists among us still prefer the older half-cock, which of course is only available on older guns.

The closing of Winchester’s historic Hartford, Connecticut factory in 2006 was a momentous event that caused a buying frenzy for Model 94s—especially pre-’64 versions—that is still having residual effects today. After a brief hiatus, the guns are now being expertly made by Miruko in Japan, still with rebounding hammers and tang safeties, but nonetheless with a quality of workmanship that rivals the guns of yesteryear. Thus, while the Winchester ‘73 may have been “the gun that won the West,” the Model 94 was the gun that galloped past the closing days of the frontier and maintained Winchester’s lever-action lead throughout the twentieth century and, now, well into the twenty-first. In fact, even today, I can’t pass up a pre-’64 Model 94 carbine without asking the price and if it is affordable, I’ll relive those early years in Pinney & Robinson’s and buy it.