50 Famous Firearms You've Got to Own: Rick Hacker's Bucket List of Guns (2015)

SMITH & WESSON

MODEL 29

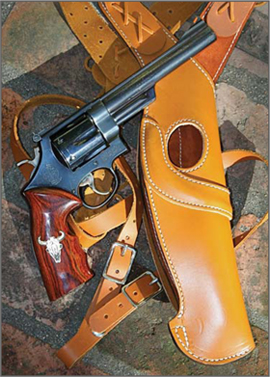

The Model 29 with an 83⁄8-inch barrel is the ideal gun for knockdown targets and hunting. The rosewood grips are from Eagle Grips.

There are only a few firearms whose legendary status is derived from the fact they can be defined by a single cartridge. One such gun is the Smith & Wesson Model 29, which was never chambered for anything other than the .44 Magnum.

The saga of the S&W Model 29 began in the early twentieth century, with a coterie of big-bore pistolero handloaders, hunters, and lawmen whose combined efforts gave us the .357 Smith & Wesson Magnum in 1935. But that wasn’t enough for those who favored pushing bigger bullets at higher velocities. Forming an unofficial group known as “The .44 Associates,” they focused on stoking up the .44 S&W Special, to see if they could take it to a world of ballistics where no cartridge had gone before.

Hacker’s 1957-era Model 29, with aftermarket ivory scrimshaw grips, was originally shipped to a gun writer in New York for testing. The Dirty Harry shoulder holster was made by The Original Dirty Harry Shoulder Holster Company of Wild Guns Leather.

Using this Galco DAO holster, the author hunted with this reissue S&W Classic Model 29 in Arizona, where he harvested a javelina of undisclosed proportions with a single shot.

Although chambered for .44 Magnum, the Model 29 digests .44 Specials with equal aplomb.

Chief among these proponents was a pistol-packing Idaho rancher named Elmer Keith, whose experimentations and gun magazine writings describing his handloading and hunting exploits put him front and center in the post-war development of what would become the .44 Magnum. The .44 Special had been developed in 1907 as a longer-cased, smokeless powder version of the .44 Russian. Smith & Wesson had created the .44 Special as an inaugural chambering for its New Century revolver, also called the First Model Hand Ejector of 1908, an ultra-sturdy double-action more popularly known as the Triple Lock (described in detail elsewhere in this book).

Due to the fact that the smokeless powder loading of the .44 Special was more accurate when kept at the blackpowder velocities approaching that of the older .44 Russian, this newer cartridge was not factory loaded to its maximum potential. Thus, with extra room in the case for more powder, it was the perfect candidate for Keith’s “.44 Special Magnum” cartridge, as he wanted to call it. His ongoing experimentations succeeded in blowing up a few cylinders, but at last he had a cartridge with which he was satisfied. He convinced Remington Arms Company to produce it, but first the case had to be lengthened a tenth of an inch more than the .44 Special to prevent shooters from duplicating Keith’s cylinder-splitting exploits, much the same as the .357 Magnum case had to be made longer than the .38 Special, upon which that round was based. The result was the .44 Remington Magnum, which held a semi-jacketed 240-grain bullet that thundered out of the barrel at 1,400 fps and struck with more than 750 ft-lbs of energy at 50 yards—almost double that of the .357 Magnum, which up until then, was the most powerful commercially available handgun cartridge. Now that title was about to be transferred to the new .44 Magnum.

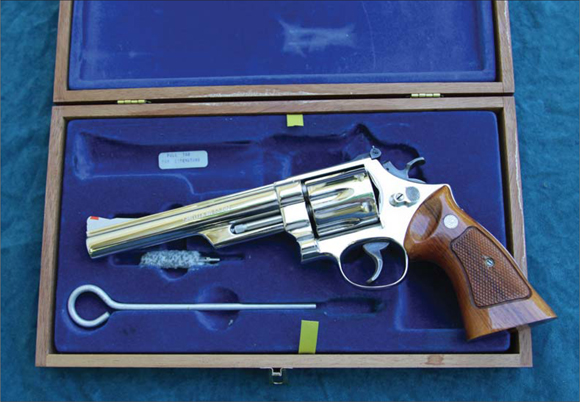

This Model 29 from the 1970s has all the bells and whistles: 61⁄2-inch barrel, nickel plating, recessed cylinder, pinned barrel, and original case and accessories—and it has never been fired!

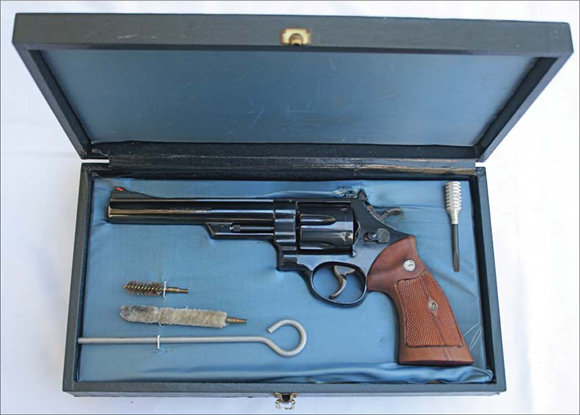

A first year production Model 29, with original case and accessories.

As for a handgun, Smith & Wesson had just the revolver, the Triple Lock, which had gone through Second and Third Model pre-war variations and now existed as the Hand Ejector Fourth Model, or 1950 Target (later known as the Model 24). But first some beefing up had to be done to ready this six-shot wheelgun for the muscular .44 Magnum. A longer cylinder closed the gap between it and a thicker barrel, both of which bumped the weight of the gun to 48 ounces, which helped tame the excessive recoil. In addition, the cylinder featured recessed chambers which enclosed the cartridge heads.

The first gun, one of five sequentially numbered prototypes built in Smith & Wesson’s Experimental Department on what would eventually become the company’s N-frame, was serial No. S121835, with the “S’ prefix denoting a hammer-block safety. On December 15, 1955 the first actual production gun, serial No. S130927 was completed. On December 29 the second gun, S130806, was presented to R.H. Coleman of Remington Arms Company, and on January 19, 1956, the revolver was officially announced to the public. It was simply called “the .44 Magnum,” and the price was $140.

The .44 Magnum was fitted with Goncala Alves target grips and offered in blued or nickel finishes, both with case hardened hammer and trigger. The revolver came with adjustable sights and a four or 61⁄2-inch barrel. The gun was housed in a black, wooden, satin-lined case embossed with “.44 Magnum” and the S&W logo on the lid. Included were a screwdriver and a cleaning rod with wire brush and cotton swab attachments. Of the next five models produced, all in January 1956, S130942 was shipped to Julian Hatcher, Technical Editor of the American Rifleman, and on January 27, No. S147220 went to Elmer Keith. Other notable gun writers of the day also received 61⁄2-inch barreled versions.

The author considers the Model 29 the only handgun a hunter needs.

Hatcher’s review broke in the March 1956 issue of the American Rifleman and other articles appeared soon after. Needless to say, the .44 Magnum was an immediate success, especially among hunters (no doubt enamored with Keith’s exploits of having dropped a deer at 600 yards with his .44 Magnum) and a few law enforcement personnel who liked the cartridge’s potential to effectively crack an automobile’s engine block. Others soon realized .44 Specials (which could also be chambered in the 44 Magnum) made this hefty handgun much more comfortable to shoot over the long term, adding flexibility to the guns popularity.

Smith & Wesson has reissued the Model 29 in both a four-inch barrel (shown) and the original 61⁄2-inch length.

The author’s factory laser-engraved four-inch Model 29, which was produced only in 2012. The custom leather rig was made by Galco Gunleather, of Phoenix, Arizona.

In 1957, reflecting a change in designation throughout the Smith & Wesson line, the .44 Magnum became the Model 29, starting with serial No. S179000. An 83⁄8-inch barrel was added in 1958, and the black wooden case was changed to mahogany in 1960. The Gun Control Act of 1968 changed the “S” serial number designation to an N-frame prefix, beginning with N1 and ending in 1983 with N96000. After that, a new serial number series featured three letters followed by four numbers. In 1979 the 61⁄2-inch barrel was shortened to six inches to standardize production with other guns, and in 1981, the counterbored cylinder chambers and pinned barrel were eliminated as being unnecessary. Later, the pivoting, hammer-mounted firing pin was changed to a frame-mounted design.

Over the years, the Model 29 underwent many variations, including Model 629 stainless steel versions, silhouette guns, and limited edition Performance Center specials, all of which proved popular. But nothing compared with the unprecedented publicity the Model 29 received in 1971, with the movie Dirty Harry, in which Clint Eastwood uttered these now-immortal words: “This is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world, and it can blow your head clean off.” Sales soared and for a while Model 29s were selling for three times their suggested retail price—if one could be found for sale, that is.

The Model 29 was discontinued in 1999, but has been brought back recently as a limited edition Classic in four and 61⁄2-inch barrels. In my collection, I own Serial No. S171XXX, which, in 1957, was shipped to a gun writer in New York, who, unfortunately, marked his test guns with a six-dot punch pattern. When I acquired it, the gun had been fired so extensively with full-house loads that I had to screw the barrel back a full turn to close the cylinder gap. This early gun still has the pre 29-1 right-hand thread on the ejector rod, so it backs out and jams after a few cylinderfuls of .44 Mags. But, as the second gun writer to own this Model 29, I feel I’m continuing a legacy started by the late Elmer Keith, Skeeter Skelton, and other members of the .44 Associates, all of whom felt that when it comes to handguns, bigger is better.