Paranormality: Why We See What Isn't There - Richard Wiseman (2011)

Chapter 2. OUT-OF-BODY EXPERIENCES

In which we hear about the scientists who attempted

to photograph the soul, discover how a rubber hand

reveals the truth about astral flying, learn how to

leave our bodies and find out how our brains

decide where we are right now.

I remember it as if it were yesterday. I had been admitted to hospital for some minor surgery and it was the night before the operation. As I drifted off to sleep something very strange happened. I felt myself slowly rise out of my bed, float up to the ceiling, and turned around to see my body sound asleep in the bed. A few seconds later I flew out of the door and whizzed full speed along the hospital corridors, eventually landing inside an operating theatre. The surgical staff were hard at work trying to remove a ketchup bottle from …

… actually, I can’t carry on with the story. It’s not that it is an especially painful memory, it’s just that I feel bad for making the whole thing up. I have never had an out-of-body experience. Sorry for wasting your time - it’s just that for years I have had to patiently listen to people as they describe their own flights of fancy and so it felt cathartic to produce one of my own.

Although fictitious, my experience does contain all of the elements associated with a ‘genuine’ out-of-body experience (or ‘OBE’). During these episodes, people feel as if they have left their body and are able to fly around without it, with many being convinced that they have found out some information that they couldn’t possibly have known otherwise. Many people report seeing their actual body during the experince, with some commenting on a strange kind of ‘astral cord’ linking their floaty self to their real self. Surveys suggest that between 10 and 20 per cent of the population has had an OBE, often when they are extremely relaxed, anaesthetized, undergoing some form of sensory deprivation such as being in a flotation tank, or on marijuana (bringing a new meaning to the term ‘getting high’).1 If the experience occurs when a person is in a life-threatening situation, it can also involve the sensation of drifting down a tunnel, seeing a bright light, and a feeling of immense serenity (these tend to be referred to as near-death experiences, or ‘NDE’). Experiences like these do seem to be surprisingly beneficial, with the vast majority of OBEers and NDEers reporting that the event has had a positive impact on their life.2

What is the explanation for these strange sensations? Are people’s souls really drifting away from their earthbound bodies? Or are these light-headed moments the result of our brains playing tricks on us? And, if that is the case, what does that say about where we are the rest of the time?

Early attempts to answer these questions involved a small group of strange scientists joining forces with the grim reaper in a bizarre search for the soul.

Dead Weight

In 1861 Boston jeweller and keen amateur photographer William Mumler made a remarkable discovery.3 As one of his self-portraits emerged from a developing tray he was astounded to see the ghostly figure of a young woman eerily floating by his side. Certain that the figure had not been present when he took the photograph, Mumler assumed that it was nothing more than a double exposure. However, when he showed the image to his friends they pointed out that the figure bore an uncanny resemblance to Mumler’s dead cousin and became convinced that he had stumbled on a way of photographing the dead. Mumler’s photograph quickly made front page news, with many journalists adopting a less than sceptical stance and promoting it as the first ever image of a spirit.

Sensing a business opportunity, Mumler promptly shut up his jewellery shop and started work as the world’s first spirit photographer. In session after session he worked hard to ensure that the spirits appeared on cue, and soon the sound of his magnesium flash pot was matched only by the noise from his till. But after a few highly successful years, trouble started. Several eagle-eyed customers noticed that some of the alleged ‘spirits’ on their photographs looked remarkably like people who had attended Mumler’s previous sittings. Other critics went further, accusing Mumler of breaking into houses, stealing photographs of the deceased and then using them to create his spirit images. The evidence stacked up and eventually Mumler was taken to court on charges of fraud. The trial proved a high-profile affair involving several well-known witnesses, including the famous showman Phineas Taylor ‘there’s a sucker born every minute’ Barnum, who accused Mumler of taking advantage of the gullible (think ‘kettle’ and ‘black’). Though acquitted of fraud, Mumler’s reputation was ruined. Never recovering from the huge legal fees it had cost him to defend the case, he died in poverty in 1884.

Ironically, the notion of spirit photography survived Mumler’s death. One eager proponent of the new fad was French researcher Dr Hyppolite Baraduc, who had a rather unusual take on the topic.4 Well aware that many of the alleged spirits bore a remarkable resemblance to the living, and eager not to dismiss the entire enterprise as bunkum, Baraduc believed that the sitters were producing the images using their psychic powers. Excited by this thought, he conducted a series of studies in which he had people hold undeveloped photographic plates and concentrate on an image. When several of the plates revealed strange blobs and shapes, Baraduc rushed to the Paris Académie de Médecine and announced his findings.

Ignoring those who thought that his results were simply photographic artefacts, Baraduc forged ahead and started to experiment with other forms of supernatural photography. Although still sceptical of mainstream spirit photography, he wondered whether it might be possible to photograph the very recently deceased and capture the soul as it left the body. He was presented with his first opportunity to photograph the dead when his 19-year-old son Andre passed away from consumption in 1907. Just a few hours after Andre’s death Baraduc did what any loving father and dedicated scientist would have done - he snapped a picture of his son’s lifeless body lying in its coffin and examined the resulting image for evidence of the soul. He was astounded to discover that the photograph showed a ‘formless, misty, wave-like mass, radiating in all directions with considerable force’. Ignoring the possibility of this being some sort of photographic artefact, or indeed the result of him psychically projecting his own thoughts onto the image, Baraduc eagerly waited for another opportunity to test his hypothesis. He didn’t have to wait long.

Just six months after the death of his son, Baraduc’s wife became seriously ill and clearly did not have long to live. Eager to make the most of the opportunity, Baraduc set up his photographic equipment at his wife’s bedside and patiently waited for her to shuffle off her mortal coil. His wife sighed three times as she passed away and Baraduc managed to take a photograph during one of her dying breaths. The image showed three luminous white ‘globes’ floating above Madame Baraduc. Elated, Baraduc took another photograph of his wife’s corpse 15 minutes later and a third roughly an hour after that. The three mysterious globes made another appearance in the first of these images and congregated into a single large globe in the second.

Baraduc was certain that he had photographed the soul. Others were not so convinced. When assessing the images in his recent book Ghosts Caught On Film, Mel Willin notes that one professional photographer suggested that the effect could well have been caused by tiny pinholes in the bellows behind the lens of the camera.5

Baraduc was not the only soul-searching scientist to work with the dying and dead. Just after the turn of the last century American physician Duncan MacDougall undertook a series of equally macabre, and now infamous studies in an attempt to discover the weight of the human soul.6 He visited his local consumptives’ home and identified six patients who were obviously very close to death (four from tuberculosis, one from diabetes, and one from unspecified causes). When each patient looked like they were just about to pop their clogs MacDougall quickly wheeled their beds onto an industrial-sized scale and waited for them to pass away. MacDougall’s laboratory notes from one of the sessions provide a vivid description of the difficulties involved in the task:

The patient … lost weight slowly at the rate of one ounce per hour due to evaporation of moisture in respiration and evaporation of sweat. During all three hours and forty minutes I kept the beam end slightly above balance near the upper limiting bar in order to make the test more decisive if it should come. At the end of three hours and forty minutes he expired and suddenly, coincident with death, the beam end dropped with an audible stroke hitting against the lower limiting bar and remaining there with no rebound. The loss was ascertained to be three-fourths of an ounce.

After another five patients had met their maker MacDougall calculated the average drop in weight at the moment of death, and proudly announced that the human soul weighed 21 grams. His findings guaranteed him a place in history and, perhaps more importantly, provided the title for a 2003 Hollywood blockbuster staring Sean Penn and Naomi Watts.

In a later study he dispatched 15 dogs on the scales and discovered no loss of weight, thus confirming his religious conviction that animals do not have souls.

When MacDougall’s findings were published in the New York Times in 1907 fellow physician Augustus P. Clarke had a field day.7 Clarke noted that at the time of death there is a sudden rise in body temperature due to the lungs no longer cooling the blood, and the subsequent rise in sweating could easily account for MacDougall’s missing 21 grams. Clarke also pointed out that dogs do not have sweat glands (thus the endless panting) and so it is not surprising that their weight did not undergo a rapid change when they died. As a result, MacDougall’s findings were confined to the large pile of scientific curiosities labelled ‘almost certainly not true’.

A few years later American researcher Dr R. A. Watters conducted several remarkable experiments involving five grasshoppers, three frogs and two mice.8 In 1894, Scottish physicist Charles Wilson was working on the summit of Ben Nevis when he experienced a ‘Brocken spectre’. This striking optical effect occurs when the sun shines behind a climber and into a mist-filled ridge. In addition to creating a large shadow of the climber, the sunlight often diffracts through the water droplets in the mist, resulting in the giant figure being surrounded by coloured rings of light. The experience set off a chain of thought in Wilson that eventually resulted in him creating a device for detecting ionizing radiation known as a cloud chamber. Wilson’s chamber consisted of a sealed glass container filled with water vapour. When an alpha or beta particle interacts with the vapour, they ionize it, resulting in visible trails that allow researchers to track the path of the particles.

It was the potential of the cloud chamber that enthralled Watters. In the early 1930s he speculated that the soul may have an ‘intra-atomic quality’ which might become visible if a living organism was exterminated inside Wilson’s device. Watters didn’t adopt Baraduc’s ‘keep it in the family’ approach to research, or share MacDougall’s scepticism about soulless animals, and so administered lethal doses of anaesthetic to various small creatures (including grasshoppers, frogs and mice), then quickly placed them into a modified cloud chamber. The resulting photographs of the dying animals did show cloud-like forms hovering above the victims’ bodies. Even more impressive to Watters was the fact that the forms frequently seemed to resemble the animals themselves. Not only had he proved the existence of a spirit form, but he had also shown that frogs’ souls, remarkably, are frog-shaped. His surviving photographs, now stored in the archives of the Society for Psychical Research in Cambridge, are less than convincing. Although the images do show large blobs of white mist, the shapes of the blobs would only resemble animals to those with the most vivid of imaginations. Once again, it is a case of the human mind seeing what it wants to see.

The ambiguous nature of the blobs proved the least of Watters’ problems. Several critics complained that it was impossible to properly assess his spectacular claims because he had not described his apparatus in sufficient detail. Others argued that the images could have been due to him failing to remove dust particles from the chamber. The final nail in Watters’ coffin came when a physics schoolteacher named Mr B. J. Hopper killed several animals in his own specially constructed cloud chamber and failed to observe any spiritual doubles.

The search for physical evidence of the soul proved less than impressive. Baraduc’s mysterious white globes could well have been due to tiny holes in the bellows of his camera, MacDougall’s loss of 21 grams at the moment of death was probably the result of idiosyncrasies in blood cooling, and Watters’ photographs of animal spirits can be explained away as a combination of dust and wishful thinking. Given this spectacular series of failures it isn’t surprising that scientists rapidly retreated from the photographing and weighing of dying humans and animals. However, reluctant to simply abandon the quest for the soul, they adopted an altogether different approach to the problem.

Anyone for tennis?

The Strange Case of the Spiritual Sneakers

Open nearly any New Age book about out-of-body and near-death experiences and you will soon read about Maria and the worn-out tennis shoe.

In April 1977 a migrant worker named Maria from Washington State suffered a severe heart attack and was rushed into Harborview Medical Centre. After three days in hospital Maria went into cardiac arrest, but was quickly resuscitated. Later that day she met with her social worker, Kimberly Clark, and explained that something deeply strange had happened during the second heart attack.9

Maria had undergone a classic out-of-body experience. As the medical staff worked to save her life, she found herself floating out of her body and looking down on the scene seeing a paper chart spewing out from a machine monitoring her vital signs. A few moments later she found herself outside the hospital looking at the surrounding roads, car parks and the outside of the building.

Maria told Clark that she had seen information that she could not have known from her bed, providing descriptions of the entrance to the emergency ward and the road around the hospital building. Although the information was correct, Clark was initially sceptical, assuming that Maria had unconsciously picked up the information when she had been admitted to the hospital. However, it was Maria’s next revelation that made Clark question her own scepticism.

Maria said that at one point on her ethereal journey she had drifted over to the north side of the building, and that an unusual object on the outside of a third floor window ledge had caught her attention. Using her mind power to zoom in, Maria saw that the object was actually a tennis shoe, and a little more zooming revealed that the shoe was well worn and the laces were tucked under the heel. Maria asked Clark if she would mind seeing if the tennis shoe actually existed.

Clark walked outside the building and looked around, but couldn’t spot anything unusual. Then she went up to the rooms in the north wing of the building and looked out of the windows. Apparently this was easier said than done, with the narrow windows meaning that she had to press her face against the glass to see onto the ledges. After much face pushing Clark was amazed to see that there was indeed an old tennis shoe sitting on one of the ledges.

‘Fifteen-love’ to the believers.

As Clark reached out onto the ledge and retrieved the shoe she noticed that it was indeed well worn and that the laces were tucked under the heel.

‘Thirty-love’.

Moreover, Clark noticed that the position of the laces would only have been apparent to someone viewing the tennis shoe from outside the building.

‘Forty-love’.

Clark published Maria’s remarkable story in 1985 and since then the case has been cited in endless books, magazine articles and websites as watertight evidence that the spirit can leave the body.

In 1996 sceptic scientists Hayden Ebbern, Sean Mulligan and Barry Beyerstein from Simon Fraser University in Canada decided to investigate the story.10 Two of the trio visited Harborview Medical Centre, interviewed Clark and located the window ledge that Maria had apparently seen all of those years before. They placed one of their own running shoes on the ledge, closed the window and stood back. Contrary to Clark’s comments, they did not need to push their faces against the glass to see the shoe. In fact, the shoe was easily visible from within the room and could even have been spotted by a patient lying in a bed.

‘Forty-fifteen’.

Next, the sceptics wandered outside the building and noticed that their experimental running shoe was surprisingly easy to spot from the hospital grounds. In fact, when they returned to the hospital one week later the shoe had been removed, further undermining the notion that it was difficult to spot.

‘Forty-thirty’.

Ebbern, Mulligan and Beyerstein believe that Maria may have overheard a comment about the shoe while sedated or half-asleep during her three days in hospital, and then incorporated this information into her out-of-body experience. They also point out that Clark didn’t publish her description of the incident until seven years after it happened, and thus there was plenty of time for it to have become exaggerated in the telling and retelling. Given that key aspects of the story were highly questionable, the trio thought that there was little reason to believe other aspects of the case, such as Maria saying that the shoe was well-worn prior to its discovery, and the lace being trapped under its heel.

‘Deuce’.

Just a few hours at the hospital revealed that the report of Maria’s infamous experience was not all that it was cracked up to be. Despite this, the story has been endlessly repeated by writers who either couldn’t be bothered to check the facts, or were unwilling to present their readers with the more sceptical side of the story. Those who believed in the existence of the soul were going to have to come up with more compelling and water-tight evidence.

‘New balls please.’

A QUICK VISUALIZATION EXERCISE

It is time for a simple two-part exercise. Both parts will require you to write in this book. You might be somewhat reluctant to do this, but it is important for three reasons. First, you will need to refer to the numbers later in this chapter and so it is helpful to have a permanent record of them. Second, if you are in a bookshop you will be morally obliged to buy the book. Third, if you have already bought the book, the chances of getting a decent resale price on eBay will be greatly diminished. OK, let's start.

Part One

Take a look at your surroundings. Perhaps you are in your home, lying in the park or sitting on the bus. Wherever, just have a look around. Now imagine how your surroundings would look if you were floating out of your body, about six feet above where you actually are, and looking down on yourself. Hold that image in your mind's eye. How clear is the image? If you had to assign it a number from one (where there is almost no image at all) to seven (a very clear and detailed image), what number would you give it? Now write down the number, in indelible blue or black ink, on the line below:

Your rating:_____

Now look around and see where you actually are, and then again imagine floating high above your body. Next, switch back to your actual location and then back to seeing the world from above your head. Now rate the ease with which you could switch between the two locations by coming up with a number between one ('Boy that was tricky') to seven ('Soooo easy'). Once again, write down the number below:

Your rating:_____

Part Two

Please rate the degree to which the following statements describe you by assigning each a number between one ('Absolutely not') and five ('Wow, it is like you have known me for years').11

|

RATING |

||

|

1. |

While watching a film I feel as if I am taking part in it. |

|

|

2. |

I can remember past events in my life with such clarity that it is like living them again. |

|

|

3. |

I can get so absorbed in listening to music that I don't notice anything else. |

|

|

4. |

I believe that stoats work too hard. |

|

|

5. |

I like to look at the clouds and try to see shapes and faces in them. |

|

|

6. |

I often become absorbed in a good book and lose track of time. |

|

Many thanks for completing the exercises. More about them later.

How to Feel Like a Desk

The infamous case of the tennis shoe on the ledge provides less than compelling evidence for the notion that people are able to float away from their bodies. Worse still, several researchers invested a considerable amount of time and effort conducting more rigorous tests of the notion and also drew a blank. For example, parapsychologist Karlis Osis tested over a hundred people who claimed that they could induce an OBE at will, asking each to leave their body, travel to a distant room and identify the randomly selected picture that had been placed there.12 The vast majority of his participants were confident that they had made the trip but as a group they scored no better than chance. Similarly, researcher John Palmer and his colleagues from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville used a variety of relaxation-based techniques to train people to have OBEs and then asked them to use their new-found ability to discover the identity of a distant target.13 In a series of studies involving over 150 participants, the experimenters failed to detect any reliable evidence of extrasensory perception.

In short, over a hundred years of scientific soul searching has ended in failure. Despite Baraduc’s attempts to photograph the spirits of his dead son and wife, MacDougall weighing the dying and Watters slaughtering several grasshoppers, the evidence didn’t stack up. As a result, the researchers changed tack and focused their attention on the information provided by those who claimed to have left their bodies. The best anecdotal case studies turned out to be a tad unreliable, and experiments involving hundreds of OBEers attempting to identify thousands of hidden targets failed to yield convincing results.

After all of this, it might appear that out of the body experiences have nothing to offer the curious mind. However, subsequent work has adopted a very different approach to the problem and, in doing so, both solved the mystery and provided an important insight into the innermost workings of your brain.

There is an old joke about a man who is trying to track down a particular room in a University Philosophy Department. He becomes lost and eventually comes across a map of the building. On the map he sees a large red arrow pointing to a particular corridor, and on the arrow it says ‘Are you here?’ It’s not a bad gag. But more importantly it raises an important issue - how do you know where you are? Or, to put it in slightly more philosophical language - why do you think that you are inside your own body?

It many ways, it seems like an odd question. After all, we seem to be inside our bodies and that is that. However, the question has hidden depths. Perhaps the greatest insights have come from a ground-breaking experiment that you can recreate in your own home using just a table, a large coffee-table book, a towel, a rubber hand and an open-minded friend.14

Start by sitting at the table and placing both of your arms on the tabletop. Next, move your right arm about six inches to the right and place the rubber hand where your right hand used to be (this is assuming that the dummy hand is a right hand - if not, use your left hand during the demonstration).

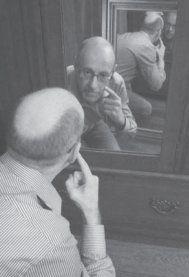

The set-up for the first part of the dummy hand experiment.

Now stand the book vertically on the tabletop between your right arm and the rubber hand, ensuring that it prevents you from seeing your right arm. Then use the towel to cover the space between your right hand and the rubber hand (see photograph below).

The dummy hand experiment in action. It is possible to appreciate the psychological impact of the experience by looking at the facial expression of the person in the photograph.

Finally, ask your friend to sit opposite you, extend their fingers and use them to stroke both your right hand and the rubber hand in the same place at the same time. After about a minute or so of stroking you will start to feel that the rubber hand is actually part of you. This feeling has interesting consequences for your real, but hidden, hand. Researchers have monitored the skin temperature of people’s hands during the study and discovered that when they believe that the rubber hand is part of them, their hidden hand becomes about half a degree colder - it is as if the brain is cutting off the blood supply to the unseen hand once it believes that it is no longer part of the body.15

It is a powerful illusion. In a similar series of studies, conducted by Vilayanur Ramachandran and described in his book Phantoms in the Brain, people were asked to place their left hand below a table, and an experimenter then stroked the hidden hand and the tabletop simultaneously.16 Once again, their sense of self shifted, with about 50 per cent of people feeling as if the wooden tabletop had become part of them.

To explain what’s going on here, let’s use a simple analogy. Imagine walking around in a new city and suddenly realizing that you are lost. The only way forward is to go hunting for a signpost. Similarly, when your brain is trying to decide where ‘you’ are it has to rely on the equivalent of signposts, namely, information from your senses.

Most of the time this works really well. Your brain might, for example, see your hand and feel pressure from your fingertip, and so correctly assume that ‘you’ are in your arm. However, in the same way that people sometimes mess around with signposts and point them in the wrong direction, so once in a while your brain will mess up. The rubber hand experiment is one of those situations. During the study, your brain ‘feels’ your left hand being stroked, ‘sees’ a dummy hand or wooden table being subjected to simultaneous stroking, concludes that ‘you’ must therefore be located in the dummy hand or table, and constructs a sense of self that is consistent with this idea. In short, the sense of where you are is not hard-wired into your brain. Instead, it is the result of your brain constantly using information from your senses to come up with a sensible guess. Because of this, the sense of ‘you’ being inside your body is subject to change at a moment’s notice.

Ramachandran’s work has important practical, as well as theoretical, implications. The majority of people who have had an arm or leg amputated often continue to feel excruciating levels of pain from their phantom limb. Ramachandran wondered whether this pain was due, in part, to their brains becoming disoriented because they were continuing to send signals to move the missing limb but then not seeing the expected movement. To test his theory, Ramachandran and his colleagues ran an unusual experiment with a group of amputees who had lost an arm.17 The research team built a two-foot-square cardboard box that was open on the top and front. They then placed a vertical mirror along the middle of the box, thus separating it into two compartments. Each participant was asked to place their arm into one of the compartments, and then orient themselves so that they could see a reflection of their arm in the mirror. From the amputee’s perspective it appeared as if they were seeing both their actual, and missing, arm. The amputee was then asked to carry out a simple movement with both of their hands at the same time, such as clenching their fists or wriggling their fingers. In short, Ramachandran’s box created the illusion of movement in their missing limb. Amazingly, the majority of the participants reported a reduction in the pain associated with their phantom limb, with some of them even asking if they could take the box home with them.

It is one thing to convince people that part of them inhabits a dummy hand or tabletop, but is it possible to use the same idea to move a person out of their entire body? Neuroscientist Bigna Lenggenhager, from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland, decided to investigate.18

If you were to take part in one of Lenggenhager’s studies you would be taken into her laboratory, asked to stand in the centre of the room and fitted with a pair of virtual reality goggles. A researcher would then place a camera a few feet behind you and feed the output into your goggles, causing you to see an image of your own back standing a few feet in front of you. Next an animated stick would appear on the image in front of you and slowly stroke your virtual back. At the same time the researchers would sneak up behind the real you and slowly stroke your back with a highlighter pen, being careful to ensure that the actual stroking matched the virtual stroking. The experimental set-up is identical to the dummy hand study, but with the ‘virtual you’ taking the place of the dummy hand and a highlighter pen replacing your friend’s hand. In the same way that stroking the dummy hand produced the strange sensation that part of you inhabited the hand, so Lenggenhager’s set-up resulted in people feeling as if their entire body was actually standing a few feet in front of themselves.

The dummy hand and virtual reality experiments demonstrate that the everyday feeling of being inside your body is constructed by the brain from sensory information. Alter that information and it is relatively easy to get people to feel as if they are outside of their bodies. Of course, people don’t have access to rubber hands and aren’t wired into virtual reality systems when they have out-of-body experiences. However, many researchers now think that this strangely counter-intuitive idea is essential to understanding the nature of these episodes.

MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL

Neuroscientist Vilayanur Ramachandran and his colleagues have created a simple way of replicating Lenggenhager's experiment without the need for a complicated and expensive virtual reality system.19 In fact, you just need two large mirrors and your finger. Arrange the two mirrors so that they are facing one another and a few feet apart. Next, angle one of the mirrors so that when you look into one mirror you see the reflection of the back of your head (see photograph). Finally, gently stroke your cheek with your finger and look at the image in the mirror.

|

|

Set-up for the mirror experiment. |

This rather unusual set-up replicates the illusion created by Lenggenhager's virtual reality system. Your brain 'feels' your cheek being stroked, 'sees' a person standing in front of you being subjected to simultaneous stroking, concludes that 'you' must therefore be standing there, and constructs a sense of self that is consistent with this idea.

When he took part in the demonstration, Ramachandran felt as if he was touching an alien or android body that was outside his own body. Many of his colleagues felt similar sensations, with some of them reporting that they wanted to say 'hello' to the person in the mirror.

At the start of this book I described how seeing psychologist Sue Blackmore on television made me realize how studying the supernatural could reveal important insights into our brains, behaviour and beliefs. Blackmore has investigated many aspects of the paranormal over the years, but much of her work has focused on the secret science behind out-of-body experiences.

Witchcraft, LSD and Tarot Cards

Sue Blackmore’s interest in the paranormal dates back to 1970 when she was a student at Oxford University and had a dramatic out-of-body experience. After several hours experimenting with a Ouija board and then relaxing with some marijuana, Sue felt herself rise out of her body, float up to the ceiling, fly across England, travel over the Atlantic, and hover around New York. Eventually she travelled back to Oxford, entered her body through her neck and finally expanded to fill the entire universe. Other than that it was a quiet night.

Upon her return to reality, Sue became fascinated with weird experiences, trained as a white witch, and eventually decided to devote herself to parapsychology. She was awarded a doctorate for work examining whether children have telepathic powers (they didn’t), went on several LSD trips to see if they would improve her psychic ability (they didn’t), and learned to read Tarot to discover if the cards could predict the future (they didn’t). After 25 years of such disappointing results Sue finally gave up the ghost and became a sceptic. For many years she examined the psychology of paranormal experiences and beliefs, trying to figure out why people experienced seemingly supernatural sensations and bought into such strange stuff. Most recently she has turned her attention to the mystery of consciousness, focusing on the ways in which the brain creates a sense of self (although, rather disappointingly, the ‘Who Am I’ tab on her website delivers a straight biography).

One of Blackmore’s early investigations tackled a question that comes up frequently when I speak about the paranormal - why do identical twins often appear to have a strange psychic bond with one another? Many proponents of psychic ability believe that this odd bond is due to telepathy. In contrast, sceptics argue that twins will often think in very similar ways because they have been raised in the same environment and have the same genetic makeup, and that such similarity will cause to them to make the same decisions and thus appear to read each other’s minds.

To help settle the issue, Blackmore brought together six sets of twins and six pairs of siblings, and conducted a two-part experiment.20 The first part was a straightforward test of telepathy. One member of each pair played the role of the ‘sender’ while the other was the ‘receiver’. The sender was presented with various randomly selected stimuli (such as a number between one and ten, an object, or a photograph), and was asked to psychically transmit the information to the receiver. No evidence of telepathy emerged from either the twins or the siblings.

In the second part of the experiment, Blackmore asked the senders to transmit the first number that came into their mind, make any drawing that appealed to them, and choose which of four photographs to send. The results suddenly changed. As predicted by the ‘twin telepathy is due to similarity’ hypothesis, there was a sudden surge in the twins’ performance. For example, when asked to think of a number between one and ten, 20 per cent of the trials involving twins produced the same number compared to just 5 per cent of those with the siblings. For the drawings, the twins again scored well, exhibiting a 21 per cent success rate compared to the siblings’ 8 per cent.

In short, the evidence indicates that twin telepathy is due to the highly similar ways in which they think and behave, and not extra-sensory perception.

Interview with Sue Blackmore

www.richardwiseman.com/paranormality/SueBlackmore.html

However, Blackmore is perhaps best known in sceptical circles for her work explaining out-of-body experiences. She took as her starting point the notion that the feeling of being located inside your body is an illusion created by your brain on the basis of incoming sensory information. Then, in the same way that a rather weird set of circumstances involving a dummy hand or a virtual reality system can cause people to believe that they are elsewhere, Blackmore wondered whether an equally strange set of circumstances might cause people to think that they had floated away from their bodies. Sue focused her attention on two elements that were central to most OBEs.

The first principle can be illustrated with the help of the image over the page.

Fix your eyes on the black dot in the centre of the image and stare at it. Providing that you are able to keep your eyes and head relatively still you will find that after about 30 seconds or so the grey area around the dot will slowly fade away. Move your head or eyes and it will jump right back again. What is going on here? It is all about a phenomenon referred to as ‘sensory habituation’. Present someone with a constant sound, image, or smell and something very peculiar happens. They slowly get more and more used to it, until eventually it vanishes from their awareness. For example, if you walk into a room that smells of freshly ground coffee, you quickly detect the rather pleasant aroma. However, stay in the room for a few minutes, and the smell will seem to disappear. In fact, the only way to re-awaken it is to walk out of the room and back in again. In the case of the illustration above your eyes slowly became blind to the grey area because it was unchanging. This exact same concept can result in the so-called ‘hedonistic treadmill’, with people quickly getting used to their new house or car, and feeling the need to buy an even bigger house or better car.

Blackmore speculated that this process was also central to OBEs. People tend to experience OBEs when they are in situations in which their brains are receiving a small amount of unchanging information from the senses. They are often robbed of any visual information because they have their eyes shut or are in the dark. In addition, they usually don’t have any tactile information because they are lying in bed, relaxing in the bath, or are on certain drugs. Under these circumstances the brain quickly becomes ‘blind’ to the small amount of information that is coming in, and so struggles to produce a coherent image of where ‘you’ are.

Like nature, brains abhor a vacuum, and so start to generate imagery about where they are and what they are doing. That is part of the reason why people are more likely to have images flowing through their mind when they shut their eyes, are in the dark or take drugs. Blackmore hypothesized that certain types of people would naturally find it easy to imagine what the world looks like when you float out of your body, and also become so absorbed in their imagery that they confuse imagination for reality, and that these individuals that would be especially likely to experience OBEs.

To test her theory Blackmore carried out several experiments.21 In fact, you have already taken part in a version of them. A few pages ago I asked you to imagine yourself being about six feet above where you actually are, and rate the clarity of your imagery and the ease with which you switched from one perspective to another. Sue presented this task to two groups of people - those that had experienced an out-of-body experience and those that had not - and obtained very different results. Those that had previously experienced floating away from themselves tended to report much more vivid images and found it much easier to switch between the two perspectives.

Blackmore also speculated that people who reported OBEs would tend to become absorbed in their experiences, so that they found it difficult to separate fact from fantasy. I also asked you to rate the degree to which six statements described you. Five of them are the types of items that you find on standard questionnaires designed to measure the degree to which you become absorbed in your experiences (I added the item about the stoats working too hard for fun). People who obtain high scores on absorption questionnaires tend to lose track of time when they watch films and television programmes, become confused about whether they have actually carried out an action or simply imagined it, and are more easily hypnotized (in the case of the five questions presented at the start of this chapter a total of 20 or more would constitute a high score). In contrast, lower scorers are more down-to-earth, practical and rarely confuse their imagination with reality (a low score would be ten or less). Blackmore’s studies involved asking OBEers and non-OBEers to complete absorption questionnaires: the OBEers consistently obtained much higher scores.

In short, Blackmore’s data suggests that people who experience OBEs are much better than others at naturally generating the type of imagery associated with the experience, and struggle to tell the difference between reality and imagination. Put these people in a situation where their bodies receive only a small amount of unchanging information about where they actually are and, just like the people taking part in the dummy hand and virtual reality experiments, they can end up believing that they are no longer located inside their bodies.

HOW TO LEAVE YOUR BODY

Understanding the real causes of out-of-body experiences can help you become a frequent flyer. The first part of the process involves developing three key psychological skills: relaxation, visualization and concentration. Let's examine each in turn.

Relaxation

'Progressive Muscle Relaxation' involves deliberately tensing various muscle groups and then releasing the tension. To try the technique, remove your shoes, loosen any tight clothing and sit in a comfortable chair in a quiet room. Focus your attention on your right foot. Gently inhale and clench the muscles in your foot as hard as possible for about five seconds. Next, exhale and release all of the tension, allowing the muscles to become loose and limp. Work your way around your body performing the procedure in the following order:

|

Right foot |

7. |

Right hand |

13. |

Abdomen |

|

2. |

Right lower leg |

8. |

Right forearm |

14. |

Chest |

|

3. |

Entire right leg |

9. |

Entire right arm |

15. |

Neck and |

|

4. |

Left foot |

10. |

Left hand |

shoulders |

|

|

5. |

Left lower leg |

11. |

Left forearm |

16. |

Face |

|

6. |

Entire left leg |

12. |

Entire left arm |

Each time, tense the appropriate body part for about five seconds and then release the tension.

Visualization

Inducing an out-of-body experience requires good visualization skills. If you are naturally good at imagining scenes and pictures in your head then that is great. If not, try the following exercise.

Imagine walking into your kitchen, taking an orange out of the cupboard and placing it on a green plate. Next, think about digging your nails into the smooth skin of the orange and starting to peel it. Think about how the orange would feel and smell. Visualize the juice coming out of the orange and onto your fingers. Imagine pulling all of the peel away and placing it on the plate. In your mind's eye, separate each of the segments and place them on the plate as well. Now look at the juicy segments. Are you salivating? Are the colours bright and sharp? Was each stage of the process vivid and did it involve all of your senses?

Repeat the exercise once every few days, trying to make it seem more realistic each time.

Concentration

The ability to focus your thoughts is also key to creating an out-of-body experience. This simple exercise will help assess and, if necessary, improve your concentration skills.

Try to count from 1 to 20 in your mind, moving onto each new number after a few seconds. However, the moment that any other thought or image enters your mind, start the count again. Initially, you will probably find this simple task surprisingly difficult, but over time you will learn how to focus your thoughts and will soon find yourself counting to 20 with no distractions.

Putting it all together

OK, it's time to try and induce an out-of-body experience. Sit in the most comfortable chair in your house. Next, stand up and take a look around. How does the room look from this perspective? Remember as many details as possible including, for example, the position of any furniture, the scene outside the window, and any pictures on the walls. Next, slowly make your way to another room. Once again, notice as much as possible on the way, including the colour of the walls, the furniture and objects that you encounter, and the type of flooring that you are walking on. To help with the process, choose four key points along the route and remember them in as much detail as possible.

Now return to the original room and sit down in the chair. Carry out the 'Progressive Relaxation Exercise'. When you feel completely relaxed, imagine a duplicate of yourself standing in front of you. To avoid the difficult (and for many, unpleasant) task of visualizing your face, imagine that your doppelganger is standing with their back to you. Try to form an image of their clothes and the way they are standing. Now, think back to what you saw when you were actually standing in that position, and imagine moving from your body into theirs. Don't worry if you don't succeed at first. This is tricky stuff and usually requires some practice.

Once you manage to feel as though you have left your own body and entered the mind of your imaginary doppelganger, try to take a few steps along the route that you mapped out, stopping at each of the four points to admire the view. If you are struggling with the movement, some researchers recommend increasing your motivation by not drinking any liquid for a few hours before the experience, and placing a glass of water in the room that you intend to visit. Also, don't be afraid of the experience - remember, you can snap back into your body at any point. After you have got the hang of inducing an out-of-body experience, you should be able to fly around the world at will, limited only by your imagination and without feeling guilty about your carbon footprint.

For decades a small number of devoted scientists attempted to prove that the soul is able to leave the body. They took photographs of recently deceased family members, weighed the dying, and asked those having out-of-body experiences to try to see pictures hidden in distant locations. The enterprise failed because you are a product of your brain and so cannot exist outside of your skull. Subsequent research into out-of-body experiences focused on finding a psychological explanation for these strange sensations. This work revealed that your brain constantly relies on information from your senses to construct the feeling that you are inside your body. Fool your senses with the help of rubber hands and virtual reality systems, and suddenly you can feel as if you are part of a table or standing a few feet in front of your body. Rob your brain of these signals and it has no idea where you are. Couple this sense of being lost with vivid imagery of flying around, and your brain convinces itself that you are floating away from your body.

Your brain automatically and unconsciously carries out the vitally important ‘where am I?’ task every moment of your waking life. Without it, you would feel that you are part of the chair you are sitting on one moment and in the floor the next. With it, you have the stable sense of constantly being inside your body. Out-of-body experiences are not paranormal and do not provide evidence for the soul. Instead, they reveal something far more remarkable about the everyday workings of your brain and body.