Impossible to Ignore: Creating Memorable Content to Influence Decisions - Carmen Simon (2016)

Chapter 6. SWEET ANTICIPATION

How to Build Excitement for What Happens Next

Carl Sandburg, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, spent the last years of his life on a farm in North Carolina. The distinguished journalist Edward Murrow (you may recognize him for his famous “Good night and good luck” sign-off) visited Sandburg for a stimulating conversation between two people in love with words. At the end of the interview, Murrow asked the poet:

“Mr. Sandburg, what is the ugliest word in the English language?”

“The ugliest word … ? The ugliest word … ? Uh … uh? The ugliest word … ?”

Most books and websites reporting this story relate it with a certain amount of detail before revealing Sandburg’s answer. One says: “The poet frowned. He reflected awhile, face knotted in thought. After a long, pregnant pause, Sandburg’s eyes brightened and returned to the reporter’s.” Another relates: “Sandburg pondered for a long minute and repeated the phrase slowly, ‘the ugliest word in the English language…. the ugliest word …’” Yet another reads: “With characteristic playfulness and drama, the wise poet pondered the question at length, seemingly searching his vast vocabulary storehouse for the appropriate answer. With a quizzical expression on his face and stroking his chin, he mused, “The ugliest word? The ugliest word … ? The ugliest word in the English language is … ‘exclusive.’”

However you come across this story, it is unlikely that you see the conclusion right away: “In an interview with a reporter, poet Carl Sandburg said that the ugliest English word is ‘exclusive.’” The ellipses in the descriptions, the mental imagery, the qualifiers, the details that prolong the thinking process … all draw us in because they create a pleasant sense of anticipation. If we find the topic relevant and anticipate a good reward, we’re motivated to linger with the text; the story turns the brain from passive to active by inviting it to think of what comes next. When we become active, we also feel more connected to what we see, and this connection brings pleasure.

There are many advantages associated with anticipation: it provides a cue that something interesting or important will happen, and it leads to improved attention, memory, and the decision to act. This is why it is worthwhile to understand anticipation and learn how to create it for your listeners in the quest to become impossible to ignore.

Something always happens next. can you get others excited about it?

Anticipation provides a good lab for testing mental models or schemas so we know how to adjust behavior and make better choices or predictions in the future. Imagine you saw an article titled “Things You Thought Were French but Aren’t.” In the article, you learn that the croissant comes from Austria, the French press was patented in Italy, the French braid originated in Greece, and an American designer is credited for the French manicure. In another situation, you find out that Russian nesting dolls, the set of hollow figures that open up to reveal progressively smaller dolls within, originated in China, were copied by the Japanese, and then were brought to Russia. On another occasion, you hear how fortune cookies are not really Chinese. In time, you start forming a new schema related to “culturally misattributed objects.” Next time you hear someone say, “This object originated in my country,” you may question that statement and not believe it immediately.

Anticipation allows us to prepare our state of attention and arousal in order to use just the right amount of energy; after all, it’s not useful to get excited if nothing worthwhile will happen, and it may not be advantageous to be fully surprised. During anticipation, the hippocampus gets a hit as well, which is why it facilitates learning and memory.

Anticipating well gives us not only a biological and cognitive advantage but a competitive advantage, too. For instance, experienced sports players in baseball, boxing, badminton, squash, tennis, or karate show superior performance compared with novices because they are good at anticipating an opponent’s next move. Sports psychologists consider these athletes as able to literally “expand the present.” The Romanian tennis star Ilie Nastase, one of the world’s top players in the 1970s, was considered to operate on “manufactured time.” This is the result of lots of practice, which turns skills into automated actions, and it allows real-time detection of relevant information about the opponent.

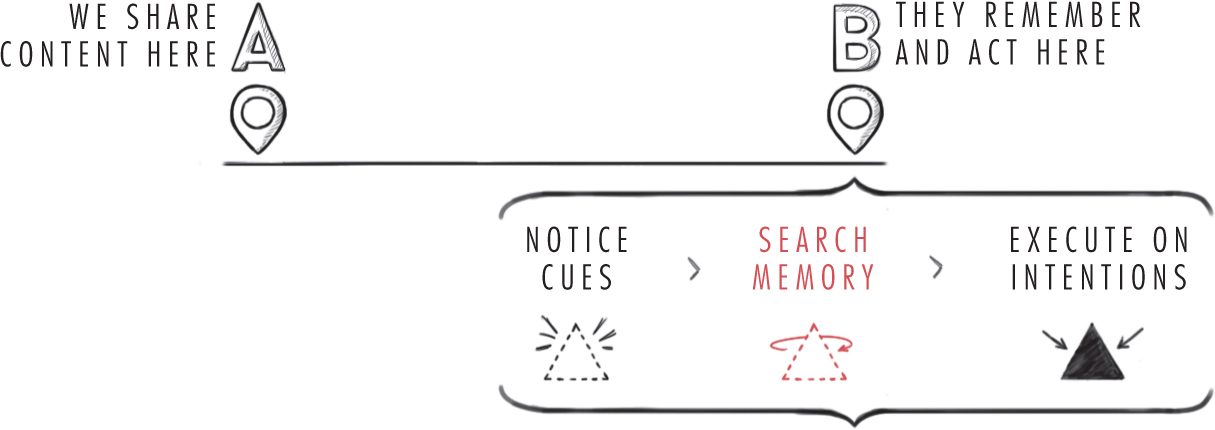

Based on these advantages of anticipation, let’s look at practical ways to create it for our audiences to impact the way they notice cues, search their memories, and act on intention at Point B. First, let’s distinguish in more detail the difference between expectation and anticipation.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EXPECTATION AND ANTICIPATION?

It is a bit of an exercise in hairsplitting because anticipation is part of expectation, and both are related to the brain’s tendency to be on fast-forward. For this discussion, let’s consider expectations as general beliefs about the world, which produce the tacit knowledge that something is going to happen. Anticipation is thinking consciously of what’s going to happen and preparing for it. While expectations run in the background and may be generic, anticipation brings forward a specific moment. For example, let’s say you’re at a restaurant and have a sip of wine left in your glass. You’re looking forward to finishing these last few drops when the waiter takes the glass away. That’s interfering with your anticipation. However, if the waiter suddenly spills coffee on your lap, that’s interfering with your expectations.

Let’s apply the same definitions of anticipation versus expectations from your audience’s perspective. When people listen to you, they hold in mind a wide range of possibilities, based on their previous knowledge, experiences, and memories of a similar context. With anticipation, you help them zoom in on a specific occurrence. And to achieve the biggest impact, as we will see in the rest of the chapter, add intrigue to the probable. After all, there is a reason for the popular term “sweet anticipation.”

SWEET ANTICIPATION

INFLUENCING ACTION WITH ANTICIPATION AND EMOTION

One of the most important aspects of anticipation versus expectation is the emotion that anticipation can evoke. “I expect the plane to land at 10” is one thing. “I anticipate my lover’s arrival on that plane” is another, and it is likely to get you to the airport. Anticipation invites others to imagine how the future unfolds, and that can impact the way they feel and make decisions.

Using the word “imagine” is a powerful way to create anticipation and emotion. Picture the messages below:

Imagine a world where every child owns a microscope.

Imagine getting rid of all the surveillance devices around you.

Imagine dragons.

While general expectations are about seeing the future (e.g., “Here is what to expect during business meetings”), anticipation is about feeling the future (e.g., “Here are three reasons to get excited about our next meeting.”). Imaginative thought is aspirational, but it’s imaginative emotions that push us into action. Anticipation is therefore a stronger expectation, a boost that gets us ready to act. Notice what happens in your brain when you read an introduction like this: “In October 2012, Jarrett Barrios, CEO of Red Cross of Eastern Massachusetts, decided to train for his first marathon. That race would be the tragic 2013 Boston Marathon, and Jarrett would be stopped at mile 25.8. This is Jarrett’s story of that day.” Would you pay attention to this unexpected cue and tune in and focus on what comes next? The anticipatory words not only include facts but also trigger emotions that make us focus on the content for a bit longer, despite possible distractions.

Anticipation is acting on expectations.

Why should we be concerned about including emotion when creating anticipation? Because people don’t act on reason alone; they act on reason and emotion. Isn’t a well-organized meeting agenda we share ahead of time worth showing up for? It is not, because people don’t act on reason alone; they act on reason and emotion.

Emotion is instrumental in decision-making. Antonio Damasio, an acclaimed neurologist, describes the condition of patients who have experienced damage to the emotional processing areas of the brain. As a result, these patients are paralyzed when making decisions. Healthy people use emotions as markers at encoding, so that at retrieval they have an easier time choosing, whereas for the damaged brain, any option looks just as good as the next one. This makes even trivial tasks such as choosing what to eat or what to wear extremely agonizing. Part of the problem is that these patients cannot anticipate feeling future outcomes: “Will I feel good or bad if I choose the chicken?” Even though they are intellectually aware of negative outcomes and can pass IQ tests successfully, they are still not capable of making decisions because the feelings about the various outcomes are not palpable.

We don’t just think about the future; we feel the future. While working with Victoria Guster-Hines, a vice president at McDonald’s, I remember brainstorming on how we could incorporate anticipation in her presentation about several business drivers for the new year. It would have been tempting to dive right into the facts. Instead, we spent a few minutes building anticipation with emotion first, so her audience could feel the facts later.

She started by relating stories about her family, and she shared photos from family events, including one of a breakfast with 70 people. She remarked how looking at the pictures reminded her of the fact that “the family you came from is as important as the family you are going to have,” and transitioned into speaking about the McFamily—the family she has at work, the family responsible for carrying out the new business drivers. This emotion-infused introduction took only 2 minutes, but those 2 minutes secured attention for 20 more afterward.

INFLUENCING THE AUDIENCE’S NEXT STEP WITH ANTICIPATION AND DOPAMINE

So far we’ve learned that anticipation has an impressive résumé: it leads to sharper focus (noticing cues), improved cognition, and faster reactions and decisions. Why does anticipation have so much power over our brains? The power stems from the “juice” that fuels it: dopamine. When we simulate the future, we are looking for rewards, and neuroscientists confirm that stimuli predicting the possibility of a reward invoke the same neuronal activity as the one triggered by the reward itself; this finding is valid in both human and animal research. Simply seeing the TV remote can get us excited in anticipation of all the fun things we get to see when we grab it.

Dopamine spikes in anticipation of rewards.

If we know how dopamine is released, we have the opportunity to impact not only the noticing of cues but also our listeners’ motivation and momentum to act on what we say. Let’s define motivation as the mental state in which we are willing to work to obtain a reward or avoid a punishment. Neuroscience research confirms that people feel more motivated to take action with a boost of dopamine.

Dopamine is transmitted from one brain region to another through a system of neurons, called the dopaminergic system. One branch of the system extends to the frontal cortex, where it impacts cognitive functions, such as thinking and short-term memory. Another branch goes to the striatum, which is responsible for motor control. Another goes to the limbic system, considered the emotional brain, which houses our reward center. Dopamine neurons signal the onset of important events and fuel the motivation to stay engaged, learn meaningful patterns, and ultimately obtain a predicted reward.

Many research findings related to dopamine mention its link to positive experiences. Neurobiological mechanisms associated with positive experiences typically include these components: wanting, liking, and learning. Consider chocolate. Wanting implies the motivation to go get it (that extra “oomph” we need to get on our feet and do something). Liking is the pleasure we get from eating it. And learning includes associations based on past experiences, which help us predict that the next experience with the same stimulus will feel just as good. Once we get a fix, we look back on the event to extract meaning and evaluate our predictive accuracy. Research has shown that even abstract pleasures, such as completing a project, admiring a painting, listening to music, or sharing opinions with others, can be as strong in generating a pleasant experience as basic sensory pleasures, such as eating something sweet.

Neuroscientists have dispelled the myth that dopamine mediates liking or the subjective pleasure we get from a reward. For example, researchers have observed that even patients with Parkinson’s still like the sweet taste of foods even though they endure severe dopamine depletion. In other words, we don’t need dopamine to like chocolate. We need dopamine to go get it.

Why should we be concerned with dopamine when we create content? It is because the presence of dopamine increases the likelihood that people have enough motivation to not only notice cues but come and get the rewards we’re promising—and return to us again.

Help people convert the prediction of a reward into the motivation to go get it.

PRACTICAL AND REALISTIC WAYS TO GENERATE DOPAMINE

So far, we know two things: (1) if there is an anticipated reward, people notice and are willing to exert some effort to get it; and (2) dopamine is released in even higher doses when there is an unexpected but pleasant reward. Let’s see how we can put these findings into practice.

Help Your Audience Anticipate a Pleasant Reward Accurately

When people anticipate a reward, dopamine neurons fire off. This is useful because you can rely on the audience exerting some effort—such as planning to attend your meeting, presentation, or training session or clicking to see your content—to get what you’re promising.

What do people find so motivating that they are willing to act? To answer that, ask another question: What pushes you into action? And do you stay motivated with the same intensity all the time? Behavioral and neuroscience findings indicate that the strength of our motivations fluctuates according to our mood. Food is appealing when we’re hungry and we’re willing to go through great effort to get it, but it is not so relevant on a full stomach. To create anticipation, we must appeal to rewards that are linked to a current state of mind.

The degree of motivation that triggers behavior is also dependent on individual traits (some people are naturally the “go-getter” type), stress, sleep deprivation, and even the state of intoxication at the time of decision-making. For example, people who are already taking some drugs (e.g., amphetamine) find it easier to stay motivated to seek rewards because dopamine levels are already high. Learned rewards do not change in this case, but the intensity of the motivation to do something does. Overall, fluctuations in mood make it tough to predict what people want to do next.

Mere knowledge about a reward is not motivation.

Although it is possible that if we are hungry or stressed or sleep deprived, we may not be intensely motivated to do much, let’s consider these states as exceptions rather than rules. And since we know the brain is constantly seeking rewards, let’s look at practical ways to account for rewards and the value of those rewards in our approach to content. But what do people consider rewarding? And how do they assign values to rewards?

The values we assign to rewards come from the effort necessary to obtain rewards (physical, mental, or financial), from the risk, and from the delay before we receive those rewards; values also depend on the social impact we associate with those rewards. Even though studies remind us that food, sleep, sex, fun, entertainment, and leisure are strong motivators, business professionals immediately ask, “How will some of these drivers reflect in the content I create for work purposes?” Someone may say, “I can’t really reference sex or food in my B2B content when I talk about Big Data.”

Researchers Adrian Gostick and Chester Elton surveyed 850,000 adults from different countries to understand what drives people at work and what differentiates dedicated employees from those just going through the motions. Their list contains five main categories (Achievers, Builders, Caregivers, Reward-Driven, and Thinkers) with a total set of 23 drivers. Achievers find these aspects rewarding: challenge, excelling, ownership, pressure, and problem solving. Builders consider these elements rewarding: developing others, friendship, purpose, service, social responsibility, and teamwork. Caregivers are motivated by empathy, family, and fun. The Reward-Driven are excited about money, prestige, recognition, and autonomy. Thinkers are motivated by creativity, excitement, impact, learning, and variety. Consider using this list (for more details, visit thecultureworks.com) to create anticipation for any message. It is effective because the motivations plug into items that have different driving power for different kinds of people.

Let’s say you are announcing a program on marketing automation, and you want to appeal to marketing professionals. You can customize the anticipatory messages depending on the type of participants you expect and what they consider rewarding. This technique enables them to anticipate rewards accurately:

“Attend this program to learn 4 techniques for marketing automation.” (Thinkers motivated by learning)

“Attend this program to be best-in-class for marketing automation.” (Reward-Driven motivated by recognition)

“Challenge yourself to learn the latest marketing automation techniques.” (Achievers motivated by challenge)

Business communicators sometimes wonder, “If I tell others what will happen during an upcoming conversation, meeting, or presentation, won’t that spoil it?” Receiving ample information ahead of time is not a letdown. This is because the proof of what will happen influences people’s feeling of power. For example, in a research study, people were asked to interact with each other; prior to the interaction, they were sent some information about their conversation partners, therefore creating anticipation about what this partner may be like (e.g., extroverted, friendly, energetic, outgoing). Some participants did not receive this information. Participants who had an informational advantage reported that they felt empowered. The reverse was also tested: having ambiguous information ahead of time led to the diffusion of power. People feel the need to control their environment, and the experience of power means having enough resources to take action.

Having information about someone else ahead of time is a source of power.

Reserve Room for Some Uncertainty

We’ve discussed helping others to anticipate accurately by looking at motivating functions related to reward. This perspective is useful because it reduces prediction error; in general, people want to feel in control and predict upcoming rewards if they are to exert any effort. However, neuroscience research reminds us that there is a functional and anatomical overlap between reward and novelty. The area of the brain that anticipates rewards is the same area that processes novelty. Novelty has intrinsic rewarding qualities, and dopamine spikes even more in the face of uncertainty because of the magnitude of the prediction error.

The anticipation of novelty also activates the hippocampus, which means that those new items are more likely to enter long-term memory. For example, in an fMRI study, participants were shown cues that predicted novel or familiar pictures with 75% accuracy. Cues that helped participants anticipate novel pictures activated the reward center of the brain more than cues associated with familiar pictures. In other words, anticipating novelty felt as good as anticipating a reward. When novelty feels rewarding, we are more motivated to explore environments that contain novel stimuli. This exploratory behavior can have biological advantages, such as in animals exploring new territories for food or business professionals exploring new fields for entrepreneurship.

In a sense, we’re dealing with a paradox: on one hand, we want to help people predict our communication accurately, but on the other, we want to provide novelty to trigger a larger spike in dopamine. Music composer and cognitive psychologist David Huron has practical recommendations for reconciling these two angles. Here is an adaptation of his views to general business communication: Let’s imagine you’re creating content that is based on a sequence of bits; these bits can be parts of a campaign, segments in a presentation, or multiple presentations in an event. Let’s say you keep all the bits the same, and the sequence is like this: AAAAA. This would give your listeners a lot of predictability because after they detect the pattern, they will know what to anticipate next and are certain they will get it (hence dopamine release). However, after a while, boredom sets in. The opposite of this technique is an ABCDE sequence, where each component is different from the previous one. This means that the brain has to wait until the E bit is finished to see what happens next, and the lack of predictability is too unsettling.

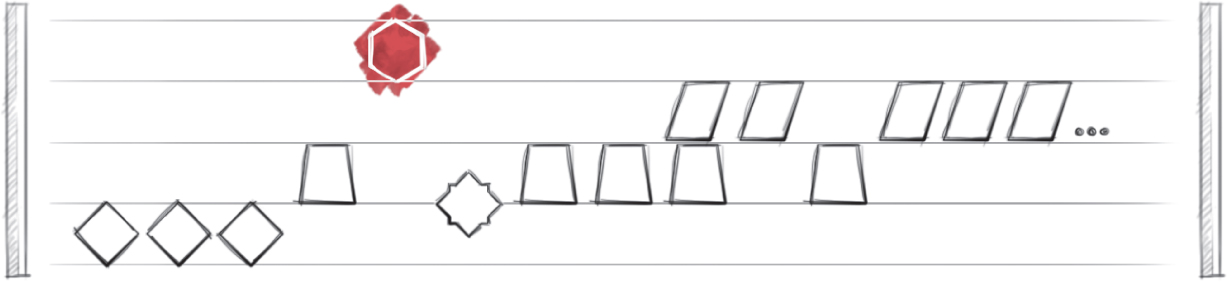

A better approach is to start with the familiar, introduce a new component, allow greater familiarity to settle in with some repetition, and then move on to other new material. Dmitry Kormann, a musician from São Paulo, Brazil, observes how composer Igor Stravinsky creates momentum in his classic The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky uses a few steps forward and one step back to introduce new elements, returns to something familiar with a modification, and then reintroduces an older item. The rhythm continues between patterns that have emerged and novelty. Check out the image below: some of the shapes stay the same, some new ones are introduced, and then there is a return to older ones with a modification; note that each time there is novelty, there is also some familiarity.

MIX PREDICTABILITY WITH NOVELTY

As you analyze your content, how does your sequence compare? Are you simply moving from one block to another in your content, or are you returning to a motif? Consider alternating between progressively larger blocks and smaller instances of familiar blocks.

We can learn about optimal content sequence based on accurate prediction and novelty from brand names. A brand name is a form of anticipation because we rely on feedback loops from the past to help us predict that our experience in the future will be similar when we use that brand again. Burberry, a brand widely known for its iconic checkered pattern (predictability at its best), is a good example of staying true to its history while allowing new designs to emerge. For example, you can still buy its signature beige trench coat, but Burberry has expanded its offerings beyond a full line of clothing to other products, such as cologne and cosmetics. Even if you can’t afford a coat, you can still send “Burberry kisses” through digital media or listen to hip new artists when you browse in its stores. The brand constantly merges the old with the new.

Ration new material.

I once worked on a presentation with a CEO for a telecom company that produces session border controllers, multiservice security gateways, and session routing proxies. These are not the sexiest topics on the planet to discuss, but we managed to create anticipation and attract attention by announcing that the presentation was about disruption and how the company was best positioned to handle new trends in the telecom industry. Announcing key market trends had been done before in an executive presentation, so to break the pattern of predictable business content, the CEO interspersed personal stories of a recent visit with his son to the Roundhouse Railroad Museum in Savannah, Georgia. Juxtaposing pictures of his young son and old trains, the CEO pointed out the state of transition his company was undergoing and the fact that history never looks like history when you’re living through it. Each time the CEO introduced new information (trends such as mobility, over-the-top applications, unified communications, cloud communication, and service diversity), he used personal stories to return to the same motif: being prepared to transition from old to new and stay relevant. This allowed his audience to enjoy a good mix of predictable and unexpected content.

TECHNIQUES FOR BUILDING ANTICIPATION WITH UNCERTAINTY

Providing a modicum of uncertainty in your communications is effective because dopamine spikes in the face of unexpected events. In general, uncertainty makes us uneasy, which is why it is often referred to as “tension.” We can tolerate some tension as long as (1) we know its degree, (2) we are reminded about the importance of the final outcome, and (3) we can tolerate the amount of delay until that outcome is realized. Let’s identify practical guidelines associated with each.

1. The Degree of Uncertainty

As a communicator, you must balance how much information to reveal (and allow listeners’ brains to predict accurately) and how much information to withhold (and get listeners ready for action, even if the action only implies people showing up to listen to you). When the outcome is certain and of little consequence, the anticipation effect is minimal. This is why asking people to join you for a “status update meeting” is a fairly dull proposition, but it can be rescued with a little work.

Compare these two invitations: “Meeting update on Tuesday. We are on track for the first three tasks, but we need to discuss task 4.” Versus “You won’t believe what we found during our last task audit and the impact it will make on the final milestone of your project.” Only use this tactic when it is truthful; avoid the click bait technique, marked by empty sensationalism.

Uncertainty can derive from the “what” or the “when” of a situation, which means you can manipulate these two variables when you create a message of anticipation. Notice what happens when you tell your partner, “I have a surprise for you tonight.” You make the “when” known, but dopamine spikes because the “what” is uncertain. You also feel the power of anticipation if your employer says, “We have a small bonus for you, which you will receive this quarter.” You know what, but you don’t know specifically when.

2. The Importance of Possible Outcomes

When we anticipate events, the brain typically estimates the worst and best possible outcomes, consciously or subconsciously. For example, if you have elbow pain, you may be estimating the best outcome to be a bit of inflammation that will go down with some Advil; the worst outcome may be a torn ligament and surgery. Your decision to see a specialist depends on how important having a functional elbow is to you. If you’re an avid tennis player, you will go through the extra effort to see a doctor even if you anticipate the diagnosis to be fairly benign. If walking or hiking is your main activity, the anticipation of elbow surgery may not bother you until it starts interfering with other outcomes that are important, such as brushing your teeth or picking up your child.

Reflect on your own messages. When you build anticipation for an upcoming event, ask from your listeners’ perspective: What are some possible outcomes? How important are they? And is there a big difference between the best and worst outcome? For example, if you want to build anticipation to entice people to attend a conference, the possible outcomes are that they fully enjoy it; they somewhat enjoy it except some sessions may be boring; they may consider all sessions to be boring, but at least there is some beneficial networking; or they totally hate it and consider it a waste of time. To minimize the difference between best and worst outcomes (“loved it” versus “hated it”), conference organizers have a few options. For instance, they set up events in venues that go beyond a predictable conference center or hotel. Imagine a business event hosted in an old warehouse, aircraft hangar, museum, botanical garden, or restored nineteenth-century sailboat. These are creative backdrops. Even if the content doesn’t appeal to them, people will likely remember the experience.

Business events sometimes showcase guests who have skills in fields other than what the event is actually about; this is another way organizers invite people to imagine optimal outcomes. For example, Orlando-based artist Rock Demarco can paint anything in 10 minutes. Picture the portrait of your CEO being done in record time to a rock’n’ roll soundtrack. For extra oomph, Demarco wears a glove with five fingerlike paintbrushes that shoot lasers. Toronto-based street painter David Johnston uses chalk to make realistic drawings at live events. He creates those 3D scenes you may have seen that tease your mind, such as drawing stairs on a flat street that give you the sensation you can go down to another level, even if there is no other level. French artist Antonin Fourneau brings an installation made of thousands of LEDs set against a wall, which he lights up by using a damp sponge. The final result is a water light graffiti show. Some may consider these entertainments nothing more than marketing fluff, so be sure to tie them to a message you want to make memorable. Otherwise, they may seem superficial.

Unusual activities do not have to cost a lot of money. In some of my brain science workshops, I take participants to an area they have not visited before, where they can interview strangers on various topics important in their fields, including leadership, communication, conflict management, marketing, sales techniques, or artificial intelligence. We receive some of the most useful insights from Starbucks baristas, university students, tourists, and hotel staff.

What are some unusual activities happening in your area? Or what performers with skills different from your teams’ can you invite to add a new take on your content or provide a break from it? Once you identify guests who can add insights, or an unexpected venue, link them to the value they provide and create anticipatory messages that make it easy for your audiences to answer, “What’s the worst that can happen?”

3. The Delay Before the Outcome Is Realized

The third aspect that impacts tension is delay, meaning the time that elapses before an outcome is realized. When you create any sort of communication, you essentially take your audience from one state to another state. The time lapse between the starting point and the destination can be short (seconds, minutes) or long (weeks, months, even years). TV news programs are very good at creating tension via delay: “What will happen to the stock market in the next two weeks? And should you go away for the holidays? All of this and more at 11.” Sometimes TV producers use foreshadowing, meaning constantly announcing what’s been shown and what happens next. For example, in a House Hunters episode on the HGTV channel, a show where people search for a dream home in various parts of the world, we may hear something like: “Abby Gordon memorized maps of Paris before ever setting foot in France. So when a job transfer to the city of her dreams came up, she took the chance. Now, after five years of renting, Abby is ready to take her relationship with the City of Light to the next level. She wants to buy an apartment that reflects her personal style. See what happens when House Hunters International settles down in Paris, France.” Then we see some commercials, and in the next scene, we hear a summary of the intro, and then view the first house that Abby visits. The formula of novelty + foreshadowing + brief summary of previous segment + novelty + foreshadowing … repeats a few times during the show.

If the topics are relevant, anticipation sustains the motivation to tune in to a program later; we appreciate it when programs release the tension with useful information, and we become disappointed when they don’t (“We stayed up for this?”). Movie trailers provoke a similar reaction. They create anticipation and tension through delay, and sometimes they deliver. The trailer said just enough to get us interested, and the entire movie is a good experience. Sometimes they disappoint: the funniest moments portrayed in the trailer were the only funny moments in the movie.

A delay must keep the promise of the anticipated reward.

In business communication, the length of the delay depends on your audience. Sometimes business audiences are in such a rush that only a short delay is effective. Here are a couple of examples:

“Do you know who is tracking your movements online? A plug-in for the Firefox browser called Lightbeam tells you which third parties want to grab hold of your data. It records every website your computer connects with, often more than the one you intended to visit. It then creates visualizations, ranging from a list to a clocklike design, to highlight who is requesting access to your data.”

“Are you sick of searching for a city parking spot? Let your phone do the work. An app can automatically determine when its user has parked, and can alert others when the spot comes open again, all without manual input. The app could also be programmed to predict when a driver is heading back to his or her car and send out notice that a parking space is about to become free.”

The tension and release happen quickly and are intended for busy professionals who only have a few seconds to listen or read brief segments. If you are working in a space where you know communication has to happen in very short bites, make sure the “reveals” that deliver on the promise of anticipation are satisfying and accurate.

If the delay is brief, find the right words for the reveal and practice them.

When your audience is fairly patient, you can create a slightly longer delay with longer sentences instead of just a few words; or if you’re writing, using an attractive title, an intriguing image, and an interesting first paragraph motivates people to read on. For example, in an article in Popular Science titled “What My Mother Learned from Einstein,” the author relates that in 1946, her mother was going to school in Cape Town, South Africa, and wrote a letter to Einstein to share her dream of becoming a scientist. The title and first paragraph invite us to read on to find out if Einstein replied. The delay is fairly brief. We find out that the writer’s mother received a response from Einstein, full of encouragement. At the time, men and women were not seen as equal, especially in the sciences, so she was surprised to receive a second letter from Einstein, reminding her that she could achieve her dreams despite her gender. The quick tension is followed by an even more rewarding release. Not only did he reply, but he wrote her twice!

In other communications, such as comprehensive marketing campaigns, meetings, or conferences, you can stretch tension for hours, days, weeks, or months. Take, for instance, the prolonged tension generated by a campaign created by Grupo W, an agency in Mexico, for Rexona Power, a men’s deodorant manufactured by Unilever. The goal of the marketing campaign was to advertise the best attribute of the deodorant: 1 million active molecules, which means extra protection for extremely active men, aged 18 to 25. The agency built curiosity around the product by creating a website and advertising a national movement in Mexico to raise 1 million clicks to “save Fermin” (about whom nothing is known). The campaign reached its goal in a few weeks, after which it launched “Who Is Fermin?” on the site. Online visitors had to overcome various obstacles, which, when solved, provided information about Fermin and whether they shared his spirit. The long delay in showing the actual product, Rexona Power, was worthwhile, as sales increased once consumers related with the “Fermin spirit,” which is living life to its fullest (and, of course, wearing the proper deodorant).

Even when an outcome is highly predictable, you can still use delay to generate that extra dose of dopamine to keep the brain engaged. We can learn from Hollywood how to do this. Imagine a highly predictable Hollywood plot in which you know the good guy will win. To delay predictability, directors:

1. Use slow motion.

2. Cut to a new scene in the middle of the predictable scene or just before the outcome is realized.

3. Turn what we thought would be a predictable shot and a decisive moment into a not-so-important one after all, with the real decisive moment happening later in the movie.

I was listening to a software executive who mentioned that he had previously worked at Apple as part of the team that developed Newton, an initial attempt at a tablet. He paused and allowed the people in the room to absorb the information. Everyone is impressed by anything related to Apple. Then he added, “Newton was the first product that Steve Jobs nixed when he came back to Apple.” What we thought would be a predictable story of success turned out to be one of failure. Everyone smiled sympathetically and immediately connected with the speaker. He spoke about his successes later on in his presentation.

Provide sweet anticipation, not an agonizing wait.

I received some great advice from Jack Daly, an entrepreneur who has sold two multimillion-dollar businesses and is now inspiring audiences all over the world to grow their businesses. “Give people a valuable tool in the first five minutes of a presentation and announce five more for later on.”

Ponder your communications right now. Can you delay gratification while sustaining attention? Are you making the reveal too soon? How long can you prolong anticipation without your audience getting discouraged or annoyed? Allow the answer to dictate the length of the delay. This mindset is important because anticipation triggers dopamine, which activates motivation and action.

KEEP IN MIND

✵ Use the word “imagine” to create anticipation and invite action. People don’t just think about the future; they feel the future, and emotion influences decision-making.

✵ People feel more motivated to take action with a boost of dopamine. The presence of dopamine increases the likelihood that people have enough motivation to not only notice cues but come and get the rewards we’re promising and return to us again.

✵ Dopamine is released when we help people anticipate a reward accurately, but also when we reserve room for some uncertainty. The area of the brain that predicts rewards is the same area that handles novelty.

✵ Dopamine spikes in the face of unexpected events. In general, uncertainty makes us uneasy, which is why it is often referred to as “tension.” We can tolerate some tension as long as (1) we know its degree, (2) we are reminded about the importance of the final outcome, and (3) we can tolerate the amount of delay until that outcome is realized.

✵ Unusual activities or performers with skills different from your teams’ are anticipation hooks and serve as strong cues that announce worthy outcomes.

✵ If the delay before realizing a promised reward is brief, find the right words for the reveal and practice them.

✵ Use foreshadowing, which means frequently giving signs of what will come next.