Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance - Angela Duckworth (2016)

Part II. GROWING GRIT FROM THE INSIDE OUT

Chapter 8. PURPOSE

Interest is one source of passion. Purpose—the intention to contribute to the well-being of others—is another. The mature passions of gritty people depend on both.

For some, purpose comes first. This is the only way I can understand a paragon of grit like Alex Scott. Ever since Alex could remember, she’d been sick. Her neuroblastoma had been diagnosed when she was a year old. Shortly after her fourth birthday, Alex told her mother, “When I get out of the hospital, I want to have a lemonade stand.” And she did. She operated her first lemonade stand before she turned five, raising two thousand dollars for her doctors to “help other kids, like they helped me.” When Alex passed away four years later, she’d inspired so many people to create their own lemonade stands that she’d raised more than a million dollars. Alex’s family has continued her legacy, and to date, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation has raised more than one hundred million dollars for cancer research.

Alex was extraordinary. But most people first become attracted to things they enjoy and only later appreciate how these personal interests might also benefit others. In other words, the more common sequence is to start out with a relatively self-oriented interest, then learn self-disciplined practice, and, finally, integrate that work with an other-centered purpose.

The psychologist Benjamin Bloom was among the first to notice this three-phase progression.

Thirty years ago, when Bloom set out to interview world-class athletes, artists, mathematicians, and scientists, he knew he’d learn something about how people reach the top of their fields. What he didn’t foresee was that he’d discover a general model of learning that applied to all the fields he studied. Despite superficial differences in their upbringing and training, all the extraordinary people in Bloom’s study had progressed through three distinct periods of development. We discussed what Bloom called the “early years” in chapter 6 on interest and “the middle years” in chapter 7 on practice. We’ve now come to the third, final, and longest phase in Bloom’s model—the “later years”—when, as he put it, “the larger purpose and meaning” of work finally becomes apparent.

When I talk to grit paragons, and they tell me that what they’re pursuing has purpose, they mean something much deeper than mere intention. They’re not just goal-oriented; the nature of their goals is special.

When I probe, asking, “Can you tell me more? What do you mean?” there sometimes follows an earnest, stumbling struggle to put how they feel into words. But always—always—those next sentences mention other people. Sometimes it’s very particular (“my children,” “my clients,” “my students”) and sometimes quite abstract (“this country,” “the sport,” “science,” “society”). However they say it, the message is the same: the long days and evenings of toil, the setbacks and disappointments and struggle, the sacrifice—all this is worth it because, ultimately, their efforts pay dividends to other people.

At its core, the idea of purpose is the idea that what we do matters to people other than ourselves.

A precocious altruist like Alex Scott is an easy-to-fathom example of other-centered purpose.

So is art activist Jane Golden, the grit paragon we met in chapter 6. Interest in art led Jane to become a muralist in Los Angeles after graduating from college. In her late twenties, Jane was diagnosed with lupus and told she didn’t have long to live. “The news came as such a shock,” she told me. “It gave me a new perspective on life.” When Jane recovered from the disease’s most acute symptoms, she realized she would outlive the doctors’ initial predictions, but with chronic pain.

Moving back to her hometown of Philadelphia, she took over a small anti-graffiti program in the mayor’s office and, over the next three decades, grew it into one of the largest public art programs in the world.

Now in her late fifties, Jane continues to work from early morning to late in the evening, six or seven days a week. One colleague likens working with her to running a campaign office the night before an election—except Election Day never comes. For Jane, those hours translate into more murals and programs, and that means more opportunities for people in the community to create and experience art.

When I asked Jane about her lupus, she admitted, matter-of-factly, that pain is a constant companion. She once told a journalist: “There are moments when I cry. I think I just can’t do it anymore, push that boulder up the hill. But feeling sorry for myself is pointless, so I find ways to get energized.” Why? Because her work is interesting? That’s only the beginning of Jane’s motivation. “Everything I do is in a spirit of service,” she told me. “I feel driven by it. It’s a moral imperative.” Putting it more succinctly, she said: “Art saves lives.”

Other grit paragons have top-level goals that are purposeful in less obvious ways.

Renowned wine critic Antonio Galloni, for instance, told me: “An appreciation for wine is something I’m passionate about sharing with other people. When I walk into a restaurant, I want to see a beautiful bottle of wine on every table.”

Antonio says his mission is “to help people understand their own palates.” When that happens, he says, it’s like a lightbulb goes off, and he wants “to make a million lightbulbs go off.”

So, while interest for Antonio came first—his parents owned a food and wine shop while he was growing up, and he “was always fascinated by wine, even at a young age”—his passion is very much enhanced by the idea of helping other people: “I’m not a brain surgeon, I’m not curing cancer. But in this one small way, I think I’m going to make the world better. I wake up every morning with a sense of purpose.”

In my “grit lexicon,” therefore, purpose means “the intention to contribute to the well-being of others.”

After hearing, repeatedly, from grit paragons how deeply connected they felt their work was to other people, I decided to analyze that connection more closely. Sure, purpose might matter, but how much does it matter, relative to other priorities? It seemed possible that single-minded focus on a top-level goal is, in fact, typically more selfish than selfless.

Aristotle was among the first to recognize that there are at least two ways to pursue happiness. He called one “eudaimonic”—in harmony with one’s good (eu) inner spirit (daemon)—and the other “hedonic”—aimed at positive, in-the-moment, inherently self-centered experiences. Aristotle clearly took a side on the issue, deeming the hedonic life primitive and vulgar, and upholding the eudaimonic life as noble and pure.

But, in fact, both of these two approaches to happiness have very deep evolutionary roots.

On one hand, human beings seek pleasure because, by and large, the things that bring us pleasure are those that increase our chances of survival. If our ancestors hadn’t craved food and sex, for example, they wouldn’t have lived very long or had many offspring. To some extent, all of us are, as Freud put it, driven by the “pleasure principle.”

On the other hand, human beings have evolved to seek meaning and purpose. In the most profound way, we’re social creatures. Why? Because the drive to connect with and serve others also promotes survival. How? Because people who cooperate are more likely to survive than loners. Society depends on stable interpersonal relationships, and society in so many ways keeps us fed, shelters us from the elements, and protects us from enemies. The desire to connect is as basic a human need as our appetite for pleasure.

To some extent, we’re all hardwired to pursue both hedonic and eudaimonic happiness. But the relative weight we give these two kinds of pursuits can vary. Some of us care about purpose much more than we care about pleasure, and vice versa.

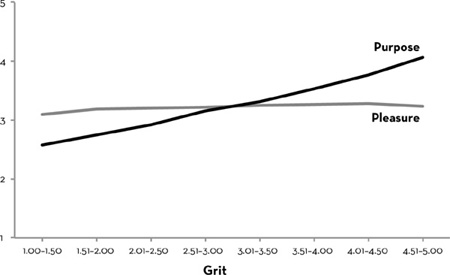

To probe the motivations that underlie grit, I recruited sixteen thousand American adults and asked them to complete the Grit Scale. As part of a long supplementary questionnaire, study participants read statements about purpose—for instance, “What I do matters to society”—and indicated the extent to which each applied to them. They did the same for six statements about the importance of pleasure—for instance, “For me, the good life is the pleasurable life.” From these responses, we generated scores ranging from 1 to 5 for their orientations to purpose and pleasure, respectively.

Below, I’ve plotted the data from this large-scale study. As you can see, gritty people aren’t monks, nor are they hedonists. In terms of pleasure-seeking, they’re just like anyone else; pleasure is moderately important no matter how gritty you are. In sharp contrast, you can see that grittier people are dramatically more motivated than others to seek a meaningful, other-centered life. Higher scores on purpose correlate with higher scores on the Grit Scale.

This is not to say that all grit paragons are saints, but rather, that most gritty people see their ultimate aims as deeply connected to the world beyond themselves.

My claim here is that, for most people, purpose is a tremendously powerful source of motivation. There may be exceptions, but the rarity of these exceptions proves the rule.

What am I missing?

Well, it’s unlikely that my sample included many terrorists or serial killers. And it’s true that I haven’t interviewed political despots or Mafia bosses. I guess you could argue that I’m overlooking a whole population of grit paragons whose goals are purely selfish or, worse, directed at harming others.

On this point, I concede. Partly. In theory, you can be a misanthropic, misguided paragon of grit. Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler, for instance, were most certainly gritty. They also prove that the idea of purpose can be perverted. How many millions of innocent people have perished at the hands of demagogues whose stated intention was to contribute to the well-being of others?

In other words, a genuinely positive, altruistic purpose is not an absolute requirement of grit. And I have to admit that, yes, it is possible to be a gritty villain.

But, on the whole, I take the survey data I’ve gathered, and what paragons of grit tell me in person, at face value. So, while interest is crucial to sustaining passion over the long-term, so, too, is the desire to connect with and help others.

My guess is that, if you take a moment to reflect on the times in your life when you’ve really been at your best—when you’ve risen to the challenges before you, finding strength to do what might have seemed impossible—you’ll realize that the goals you achieved were connected in some way, shape, or form to the benefit of other people.

In sum, there may be gritty villains in the world, but my research suggests there are many more gritty heroes.

Fortunate indeed are those who have a top-level goal so consequential to the world that it imbues everything they do, no matter how small or tedious, with significance. Consider the parable of the bricklayers:

Three bricklayers are asked: “What are you doing?”

The first says, “I am laying bricks.”

The second says, “I am building a church.”

And the third says, “I am building the house of God.”

The first bricklayer has a job. The second has a career. The third has a calling.

Many of us would like to be like the third bricklayer, but instead identify with the first or second.

Yale management professor Amy Wrzesniewski has found that people have no trouble at all telling her which of the three bricklayers they identify with. In about equal numbers, workers identify themselves as having:

a job (“I view my job as just a necessity of life, much like breathing or sleeping”),

a career (“I view my job primarily as a stepping-stone to other jobs”), or

a calling (“My work is one of the most important things in my life”).

Using Amy’s measures, I, too, have found that only a minority of workers consider their occupations a calling. Not surprisingly, those who do are significantly grittier than those who feel that “job” or “career” more aptly describes their work.

Those fortunate people who do see their work as a calling—as opposed to a job or a career—reliably say “my work makes the world a better place.” And it’s these people who seem most satisfied with their jobs and their lives overall. In one study, adults who felt their work was a calling missed at least a third fewer days of work than those with a job or a career.

Likewise, a recent survey of 982 zookeepers—who belong to a profession in which 80 percent of workers have college degrees and yet on average earn a salary of $25,000—found that those who identified their work as a calling (“Working with animals feels like my calling in life”) also expressed a deep sense of purpose (“The work that I do makes the world a better place”). Zookeepers with a calling were also more willing to sacrifice unpaid time, after hours, to care for sick animals. And it was zookeepers with a calling who expressed a sense of moral duty (“I have a moral obligation to give my animals the best possible care”).

I’ll point out the obvious: there’s nothing “wrong” with having no professional ambition other than to make an honest living. But most of us yearn for much more. This was the conclusion of journalist Studs Terkel, who in the 1970s interviewed more than a hundred working adults in all sorts of professions.

Not surprisingly, Terkel found that only a small minority of workers identified their work as a calling. But it wasn’t for lack of wanting. All of us, Terkel concluded, are looking for “daily meaning as well as daily bread … for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying.”

The despair of spending the majority of our waking hours doing something that lacks purpose is vividly embodied in the story of Nora Watson, a twenty-eight-year-old staff writer for an institution publishing health-care information: “Most of us are looking for a calling, not a job,” she told Terkel. “There’s nothing I would enjoy more than a job that was so meaningful to me that I brought it home.” And yet, she admitted to doing about two hours of real work a day and spending the rest of the time pretending to work. “I’m the only person in the whole damn building with a desk facing the window instead of the door. I just turn myself around from all that I can.

“I don’t think I have a calling—at this moment—except to be me,” Nora said toward the end of her interview. “But nobody pays you for being you, so I’m at the Institution—for the moment… .”

In the course of his research, Terkel did meet a “happy few who find a savor in their daily job.” From an outsider’s point of view, those with a calling didn’t always labor in professions more conducive to purpose than Nora. One was a stonemason, another a bookbinder. A fifty-eight-year-old garbage collector named Roy Schmidt told Terkel that his job was exhausting, dirty, and dangerous. He knew most other occupations, including his previous office job, would be considered more attractive to most people. And yet, he said: “I don’t look down on my job in any way… . It’s meaningful to society.”

Contrast Nora’s closing words with the ending of Roy’s interview: “I was told a story one time by a doctor. Years ago, in France … if you didn’t stand in favor with the king, they’d give you the lowest job, of cleaning the streets of Paris—which must have been a mess in those days. One lord goofed up somewhere along the line, so they put him in charge of it. And he did such a wonderful job that he was commended for it. The worst job in the French kingdom and he was patted on the back for what he did. That was the first story I ever heard about garbage where it really meant something.”

In the parable of the bricklayers, everyone has the same occupation, but their subjective experience—how they themselves viewed their work—couldn’t be more different.

Likewise, Amy’s research suggests that callings have little to do with formal job descriptions. In fact, she believes that just about any occupation can be a job, career, or calling. For instance, when she studied secretaries, she initially expected very few to identify their work as a calling. When her data came back, she found that secretaries identified themselves as having a job, career, or calling in equal numbers—just about the same proportion she’d identified in other samples.

Amy’s conclusion is that it’s not that some kinds of occupations are necessarily jobs and others are careers and still others are callings. Instead, what matters is whether the person doing the work believes that laying down the next brick is just something that has to be done, or instead something that will lead to further personal success, or, finally, work that connects the individual to something far greater than the self.

I agree. How you see your work is more important than your job title.

And this means that you can go from job to career to calling—all without changing your occupation.

“What do you tell people,” I recently asked Amy, “when they ask you for advice?”

“A lot of people assume that what they need to do is find their calling,” she said. “I think a lot of anxiety comes from the assumption that your calling is like a magical entity that exists in the world, waiting to be discovered.”

That’s also how people mistakenly think about interests, I pointed out. They don’t realize they need to play an active role in developing and deepening their interests.

“A calling is not some fully formed thing that you find,” she tells advice seekers. “It’s much more dynamic. Whatever you do—whether you’re a janitor or the CEO—you can continually look at what you do and ask how it connects to other people, how it connects to the bigger picture, how it can be an expression of your deepest values.”

In other words, a bricklayer who one day says, “I am laying bricks” might at some point become the bricklayer who recognizes “I am building the house of God.”

Amy’s observation that the same individual in the same occupation can at different times think of it as a job, career, or calling brought to mind Joe Leader.

Joe is a senior vice president at NYC Transit. Basically, he’s the New York City subway’s lead engineer. It’s a task of almost unimaginable proportions. Annually, more than 1.7 billion trips are taken on the city’s subways, making it the busiest subway system in the United States. There are 469 stations. Laid end to end, the tracks for the subway system would reach all the way to Chicago.

As a young man, Leader wasn’t looking for a calling. He was looking to pay back student loans.

“When I was coming out of college,” he told me, “my biggest concern was just getting a job. Any job. Transit came to our campus to recruit engineers, and I got hired.”

As an intern, Leader was assigned to work on the tracks. “I threw in rails, I was pulling ties, I was doing cable work for the third rail.”

Not everyone would find that work interesting, but Joe did. “It was fun. When I was first on the job, and all my buddies were business or computer guys, we used to go out, and on the way home from the bars in the evening, they used to run up and down a platform and say, ‘Joe, what’s this, what’s this?’ I used to tell them: that’s a third-rail insulator, that’s an insulated joint. To me, it was fun.”

So, interest was the seed of his passion.

Joe soon ended up doing a lot of planning work, which he also enjoyed. As his interests and expertise deepened, and he started to distinguish himself, he began to see transit engineering as a long-term career. “On my days off, I went down to the laundromat to do the laundry. You know those big tables for folding your clothes? Well, all the women used to laugh because I’d bring my engineering drawings and lay them out and work on them. I really fell in love with that part of the job.”

Within a year, Joe said he began to look at his work differently. Sometimes, he’d look at a bolt or rivet and realize that some fellow had put that in decades ago, and here it was, still in the same place, still making the trains run, still helping people to get where they needed to be.

“I began to feel like I was making a contribution to society,” he told me. “I understood I was responsible for moving people every single day. And when I became a project manager, I would walk away from these big installation jobs—you know, a hundred panels or a whole interlocking [of signals]—and I knew that what we’d done was going to last for thirty years. That was when I felt I had a vocation, or I would say, a calling.”

To hear Joe Leader talk about his work might make you wonder if, after a year of not finding your work to be a calling, you should give up hope. Among her MBA students, Amy Wrzesniewski finds that many give their job only a couple of years before concluding that it couldn’t possibly be their life’s passion.

It may comfort you to know that it took Michael Baime much longer.

Baime is a professor of internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. You might think his calling is to heal and to teach. That’s only partly right. Michael’s passion is well-being through mindfulness. It took him years to integrate his personal interest in mindfulness with the other-centered purpose of helping people lead healthier, happier lives. Only when interest and purpose melded did he feel like he was doing what he’d been put on this planet to do.

I asked Michael how he got interested in mindfulness, and he took me all the way back to his boyhood. “I was looking up at the sky,” he told me. “And the strangest thing happened. I felt like I was actually getting lost in the sky. I felt it as a sort of opening, like I was becoming much larger. It was the most wonderful experience I’ve ever had.”

Later, Michael found that he could make the same thing happen just by paying attention to his own thoughts. “I became obsessed,” he told me. “I didn’t know what to call it, but I would do it all the time.”

Several years later, Michael was browsing in a bookstore with his mother when he came upon a book that described his experience exactly. The book was by Alan Watts, a British philosopher who wrote about meditation for Western audiences long before it became fashionable.

With his parents’ encouragement, Michael took classes in meditation throughout high school and college. As graduation approached, he had to decide what to do next. Professional meditator was not an actual full-time occupation. He decided to become a doctor.

Several years into medical school, Michael confessed to one of his meditation teachers, “This isn’t really what I want to do. This isn’t right for me.” Medicine was important, but it didn’t match up with his deepest personal interests. “Stay,” said the teacher. “You’ll help more people if you become a doctor.”

Michael stayed.

After finishing his coursework, Michael says, “I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. To kind of tread water, I just signed up for the first year of internship.”

To his surprise, he enjoyed practicing medicine. “It was a fine way to be helpful to people. It wasn’t like medical school, which isn’t so much about helping people as cutting apart cadavers and memorizing the Krebs cycle.” Rapidly, he progressed from intern to fellow to running the medical clinic to becoming the assistant director of residency and, finally, chief of general internal medicine.

Still, medicine wasn’t quite what Michael would consider a calling.

“As I practiced, I realized that the thing many of my patients really needed wasn’t another prescription or X-ray, but actually what I’d been doing for myself since I was a kid. What many patients needed was to stop and breathe and fully connect with their lived experience.”

That realization led Michael to create a meditation class for patients with serious health conditions. That was in 1992. Since then, he’s expanded the program and, just this year, taken it on as a full-time occupation. To date, about fifteen thousand patients, nurses, and physicians have been trained.

Recently, I asked Michael to give a lecture on mindfulness for local schoolteachers. On the day of his talk, he stepped up to the podium and looked intently at his audience. One by one, he made eye contact with each of the seventy educators who’d given up their Sunday afternoon to hear what he had to say. There was a long pause.

And then, with a smile I can only describe as radiant, he began: “I have a calling.”

I was twenty-one when I first experienced the power of a purposeful top-level goal.

In the spring of my junior year in college, I went to the career services center to find something to do that summer. Turning the pages of an enormous three-ring binder labeled SUMMER PUBLIC SERVICE, I came across a program called Summerbridge. The program was looking for college students to design and teach summer enrichment classes for middle school students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Teaching kids for a summer sounds like a good idea, I thought. I could teach biology and ecology. I’ll show them how to make a solar oven out of tinfoil and cardboard. We’ll roast hot dogs. It’ll be fun.

I didn’t think, This experience is going to change everything.

I didn’t think, Sure, you’re premed now, but not for long.

I didn’t think, Hold on tight—you’re about to discover the power of purpose.

To be honest, I can’t tell you much about that summer. The details escape me. I do know I woke long before dawn each day, including weekends, to prepare for my classes. I do know I worked long into the night. I remember specific kids, and certain moments. But it wasn’t until I returned home and had a moment to reflect that I realized what had happened. I’d glimpsed the possibility that a child’s connection with a teacher can be life-changing—for both.

When I returned to campus that fall, I sought out other students who’d taught at Summerbridge programs. One of these students, Philip King, happened to live in the same dorm. Like me, he felt a palpable urgency to start another Summerbridge program. The idea was too compelling. We couldn’t not try.

We had no money, no idea how to start a nonprofit, no connections, and, in my case, nothing but skepticism and worry from parents convinced this was a catastrophically stupid way to use a Harvard education.

Philip and I had nothing and, yet, we had exactly what we needed. We had purpose.

As anyone who has started an organization from scratch can tell you, there are a million tasks, big and small, and no instruction manual for any of them. If Philip and I were doing something that was merely interesting, we couldn’t have done it at all. But because creating this program was in our minds—and in our hearts—so overwhelmingly important for kids, it gave us a courage and energy neither of us had ever known before.

Because we weren’t asking for ourselves, Philip and I found the gumption to knock on the doors of just about every small business and restaurant in Cambridge, asking for donations. We found the patience to sit in countless waiting rooms of powers-that-be. We waited and waited, sometimes hours on end, until these authority figures had time to see us. Then we found the stubbornness to keep asking and asking until we secured what we needed.

And so it went for everything we had to do—because we weren’t doing it for ourselves, we were doing it for a greater cause.

Two weeks after Philip and I graduated, we opened the doors to the program. That summer, seven high school and college students discovered what it was like to be a teacher. Thirty fifth-grade boys and girls discovered what it was like to spend their summer vacation learning, studying, working hard, and—though it may have seemed impossible before they actually did it—having fun at the same time.

That was more than twenty years ago. Now called Breakthrough Greater Boston, the program has grown far beyond what Philip and I could have imagined, providing tuition-free, year-round academic enrichment for hundreds of students every year. To date, more than a thousand young men and women have taught in the program, many of whom have gone on to pursue full-time careers in education.

Summerbridge led me to pursue teaching. Teaching led me to an enduring interest in helping children do so much more with their lives than they might ever dream possible.

And yet …

For me, teaching wasn’t enough. Still unfulfilled was the little girl in me who loved science, who was fascinated by human nature, who, when she was sixteen and had a chance to take a summer enrichment class, picked—of all the courses in the catalog—psychology.

Writing this book made me realize that I’m someone who had an inkling about my interests in adolescence, then some clarity about purpose in my twenties, and finally, in my thirties, the experience and expertise to say that my top-level, life-organizing goal is, and will be until my last breath: Use psychological science to help kids thrive.

One reason my dad was so upset about Summerbridge is that he loves me. He thought I would sacrifice my welfare for the well-being of other people who, frankly, he didn’t love as much as his own daughter.

Indeed, the concepts of grit and purpose might, in principle, seem to conflict. How is it possible to stay narrowly focused on your own top-level goal while also having the peripheral vision to worry about anyone else? If grit is about having a pyramid of goals that all serve a single personal objective, how do other people fit into the picture?

“Most people think self-oriented and other-oriented motivations are opposite ends of a continuum,” says my colleague and Wharton professor Adam Grant. “Yet, I’ve consistently found that they’re completely independent. You can have neither, and you can have both.” In other words, you can want to be a top dog and, at the same time, be driven to help others.

Adam’s research demonstrates that leaders and employees who keep both personal and prosocial interests in mind do better in the long run than those who are 100 percent selfishly motivated.

For instance, Adam once asked municipal firefighters, “Why are you motivated to do your work?” He then tracked their overtime hours over the next two months, expecting firefighters who were more motivated to help others to demonstrate the greatest grit. But many of those who were driven to help others worked fewer overtime hours. Why?

A second motivation was missing: interest in the work itself. Only when they enjoyed the work did the desire to help others result in more effort. In fact, firefighters who expressed prosocial motives (“Because I want to help others through my work”) and intrinsic interest in their work (“Because I enjoy it”) averaged more than 50 percent more overtime per week than others.

When Adam asked the same question—“Why are you motivated to do your work?”—of 140 fund-raisers at a call center for a public university, he found nearly identical results. Only the fund-raisers who expressed stronger prosocial motives and who found the work intrinsically engaging made more calls and, in turn, raised more money for the university.

Developmental psychologists David Yeager and Matt Bundick find the same pattern of results in adolescents. For example, in one study, David interviewed about a hundred adolescents, asking them to tell him, in their own words, what they wanted to be when they grew up, and why.

Some talked about their future in purely self-oriented terms (“I want to be a fashion designer because it’s a fun thing to do… . What’s important … is that you really enjoy [your career]”).

Others only mentioned other-oriented motives (“I want to be a doctor. I want to help people out …”).

And, finally, some adolescents mentioned both self- and other-oriented motives: “If I was a marine biologist, I would push [to] keep everything clean… . I would pick a certain place and go help that place out, like the fish and everything… . I’ve always loved having fish tanks and fish because they get to swim and it’s, like, free. It’s like flying underwater or something.”

Two years later, young people who’d mentioned both self- and other-oriented motives rated their schoolwork as more personally meaningful than classmates who’d named either motive alone.

For many of the grit paragons I’ve interviewed, the road to a purposeful, interesting passion was unpredictable.

Aurora and Franco Fonte are Australian entrepreneurs whose facilities services company has 2,500 employees and generates more than $130 million in annual revenue.

Twenty-seven years ago, Aurora and Franco were newly married and dead broke. They got the idea to start a restaurant but didn’t have enough money to launch one. Instead, they began cleaning shopping malls and small office buildings—not out of any sense of calling, but because it paid the bills.

Soon enough, their career ambitions took a turn. They could see a brighter future in building maintenance than in hospitality. They both worked ferociously hard, putting in eighty-hour weeks, sometimes with their infant children in carriers strapped across their chests, scrubbing the bathroom tiles in their customers’ buildings as if they were their own.

Through all the ups and downs—and there were many—Franco told me: “We always persevered. We didn’t give in to obstacles. There was no way were going to let ourselves fail.”

I confessed to Aurora and Franco that it was hard for me to imagine how cleaning bathrooms—or even building a multimillion-dollar corporation that cleans bathrooms—could feel like a calling.

“It’s not about the cleaning,” Aurora explained, her voice tightening with emotion. “It’s about building something. It’s about our clients and solving their problems. Most of all, it’s about the incredible people we employ—they have the biggest souls, and we feel a huge responsibility toward them.”

According to Stanford developmental psychologist Bill Damon, such a beyond-the-self orientation can and should be deliberately cultivated. Now in the fifth decade of his distinguished career, Bill studies how adolescents learn to lead lives that are personally gratifying and, at the same time, beneficial to the larger community. The study of purpose, he says, is his calling.

In Bill’s words, purpose is a final answer to the question “Why? Why are you doing this?”

What has Bill learned about the origins of purpose?

“In data set after data set,” he told me, “there’s a pattern. Everyone has a spark. And that’s the very beginning of purpose. That spark is something you’re interested in.”

Next, you need to observe someone who is purposeful. The purposeful role model could be a family member, a historical figure, a political figure. It doesn’t really matter who it is, and it doesn’t even matter whether that purpose is related to what the child will end up doing. “What matters,” Bill explained, “is that someone demonstrates that it’s possible to accomplish something on behalf of others.”

In fact, he can’t remember a single case in which the development of purpose unfolded without the earlier observation of a purposeful role model. “Ideally,” he said, “the child really gets to see how difficult a life of purpose is—all the frustrations and the obstacles—but also how gratifying, ultimately, it can be.”

What follows is a revelation, as Bill put it. The person discovers a problem in the world that needs solving. This discovery can come in many ways. Sometimes from personal loss or adversity. Sometimes from learning about the loss and adversity confronting others.

But seeing that someone needs our help isn’t enough, Bill hastened to add. Purpose requires a second revelation: “I personally can make a difference.” This conviction, this intention to take action, he says, is why it’s so important to have observed a role model enact purpose in their own life. “You have to believe that your efforts will not be in vain.”

Kat Cole is someone who had a role model for purpose-driven grit.

I met Kat when she was the thirty-five-year-old president of the Cinnabon bakery chain. If you listen to her story without reflecting much on it, you might dub it “rags to riches,” but if you lean in and pay attention you’ll hear a different theme: “from poverty to purpose.”

Kat grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. Her mother, Jo, worked up the courage to leave Kat’s alcoholic father when Kat was nine. Jo worked three jobs to make enough money to support Kat and her two sisters, and yet still found time to be a giver. “She’d be baking for someone, running an errand for someone—she intuitively saw every small opportunity to do something for others. Everyone she got to know, whether they were coworkers or just people in the community, became family to her.”

Kat emulated both her mother’s work ethic and her profound desire to be helpful.

Before we get to Kat’s motivation, though, let’s consider her unlikely ascent up the corporate ladder. Kat’s résumé begins with a stint, at age fifteen, selling clothes at the local mall. At eighteen, she was old enough to waitress. She got a job as a “Hooters girl” and one year later was asked to help open the first Hooters restaurant in Australia. Ditto for Mexico City, the Bahamas, and then Argentina. By twenty-two, she was running a department of ten. By twenty-six, she was vice president. As a member of the executive team, Kat helped expand the Hooters franchise to more than four hundred sites in twenty-eight countries. When the company was bought by a private equity firm, Kat, at age thirty-two, had such an impressive track record that Cinnabon recruited her to be its president. Under Kat’s watch, Cinnabon sales grew faster than they had in more than a decade, and within four years exceeded one billion dollars.

Now let’s consider what makes Kat tick.

One time early in Kat’s waitressing days at Hooters, the cooks quit in the middle of their shift. “So,” she told me matter-of-factly, “I went back with the manager and helped cook the food so all the tables got served.”

Why?

“First of all, I was surviving off tips. That’s how I paid my bills. If people didn’t get their food, they wouldn’t pay their check, and they certainly wouldn’t leave a tip. Second, I was so curious to see if I could do it. And third, I wanted to be helpful.”

Tips and curiosity are pretty self-oriented motivations, but wanting to be helpful is, quite literally, other-oriented. Here was an example of how a single action—jumping behind the stove to make food for all those waiting customers—benefited the individual and the people around her.

The next thing Kat knew, she was training kitchen employees and helping out with the back-office operations. “Then one day, the bartender needed to leave early, and the same thing happened. Another day, the manager quit, and I learned how to run a shift. In the course of six months, I’d worked every job in the building. Not only did I work those jobs, I became the trainer to help teach all those roles to other people.”

Jumping into the breach and being especially helpful wasn’t a calculated move to get ahead in the corporation. Nevertheless, that beyond-the-call-of-duty performance led to an invitation to help open international locations, which led to a corporate executive position, and so on.

Not so coincidentally, it’s the sort of thing her mother, Jo, would have done. “My passion is to help people,” Jo told me. “No matter at business, or away from business, if you need somebody to come over and build something, or help out in some way, I’m that person who wants to be there for you. To me, any success I’ve had, it’s because I love to share. There’s no reserve in me—whatever I have, I’m willing to give to you or anyone else.”

Kat attributes her philosophy to her mother, who raised her “to work hard and give back.” And that ethic still guides her today.

“Gradually, I became more and more aware that I was very good at going into new environments and helping people realize they’re capable of more than they know. I was discovering that this was my thing. And I started to realize that if I could help people—individuals—do that, then I could help teams. If I could help teams, I could help companies. If I could help companies, I could help brands. If I could help brands, I could help communities and countries.”

Not long ago, Kat posted an essay on her blog, titled “See What’s Possible, and Help Others Do the Same.” “When I am around people,” Kat wrote, “my heart and soul radiate with the awareness that I am in the presence of greatness. Maybe greatness unfound, or greatness underdeveloped, but the potential or existence of greatness nevertheless. You never know who will go on to do good or even great things or become the next great influencer in the world—so treat everyone like they are that person.”

Whatever your age, it’s never too early or late to begin cultivating a sense of purpose. I have three recommendations, each borrowed from one of the purpose researchers mentioned in this chapter.

David Yeager recommends reflecting on how the work you’re already doing can make a positive contribution to society.

In several longitudinal experiments, David Yeager and his colleague Dave Paunesku asked high school students, “How could the world be a better place?” and then asked them to draw connections to what they were learning in school. In response, one ninth grader wrote, “I would like to get a job as some sort of genetic researcher. I would use this job to help improve the world by possibly engineering crops to produce more food… .” Another said, “I think that having an education allows you to understand the world around you… . I will not be able to help anyone without first going to school.”

This simple exercise, which took less than a class period to complete, dramatically energized student engagement. Compared to a placebo control exercise, reflecting on purpose led students to double the amount of time they spent studying for an upcoming exam, work harder on tedious math problems when given the option to watch entertaining videos instead, and, in math and science classes, bring home better report card grades.

Amy Wrzesniewski recommends thinking about how, in small but meaningful ways, you can change your current work to enhance its connection to your core values.

Amy calls this idea “job crafting,” and it’s an intervention she’s been studying with fellow psychologists Jane Dutton, Justin Berg, and Adam Grant. This is not a Pollyanna, every-job-can-be-nirvana idea. It is, simply, the notion that whatever your occupation, you can maneuver within your job description—adding, delegating, and customizing what you do to match your interests and values.

Amy and her collaborators recently tested this idea at Google. Employees working in positions that don’t immediately bring the word purpose to mind—in sales, marketing, finance, operations, and accounting, for example—were randomly assigned to a job-crafting workshop. They came up with their own ideas for tweaking their daily routines, each employee making a personalized “map” for what would constitute more meaningful and enjoyable work. Six weeks later, managers and coworkers rated the employees who attended this workshop as significantly happier and more effective.

Finally, Bill Damon recommends finding inspiration in a purposeful role model. He’d like you to respond in writing to some of the questions he uses in his interview research, including, “Imagine yourself fifteen years from now. What do you think will be most important to you then?” and “Can you think of someone whose life inspires you to be a better person? Who? Why?”

When I carried out Bill’s exercise, I realized that the person in my life who, more than anyone, has shown me the beauty of other-centered purpose is my mom. She is, without exaggeration, the kindest person I’ve ever met.

Growing up, I didn’t always appreciate Mom’s generous spirit. I resented the strangers who shared our table every Thanksgiving—not just distant relatives who’d recently emigrated from China, but their roommates, and their roommates’ friends. Pretty much anyone who didn’t have a place to go who happened to run into my mom in the month of November was warmly welcomed into our home.

One year, Mom gave away my birthday presents a month after I’d unwrapped them, and another, she gave away my sister’s entire stuffed animal collection. We threw tantrums and wept and accused her of not loving us. “But there are children who need them more,” she said, genuinely surprised at our reaction. “You have so much. They have so little.”

When I told my father I wouldn’t be taking the MCAT exam for medical school and, instead, would devote myself to creating the Summerbridge program, he was apoplectic. “Why do you care about poor kids? They’re not family! You don’t even know them!” I now realize why. All my life, I’d seen what one person—my mother—could do to help many others. I’d witnessed the power of purpose.