The Battle of Aleppo: The History of the Ongoing Siege at the Center of the Syrian Civil War (2016)

Chapter 2: The Assad Regime

"During its decades of rule.. the Assad family developed a strong political safety net by firmly integrating the military into the government. In 1970, Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, seized power after rising through the ranks of the Syrian armed forces, during which time he established a network of loyal Alawites by installing them in key posts. In fact, the military, ruling elite, and ruthless secret police are so intertwined that it is now impossible to separate the Assad government from the security establishment.. So.. the government and its loyal forces have been able to deter all but the most resolute and fearless oppositional activists. In this respect, the situation in Syria is to a certain degree comparable to Saddam Hussein’s strong Sunni minority rule in Iraq." - Foreign Policy magazine editorial, 2011

When Bashar al-Assad was born on September 11, 1965, he became his father Hafez’s third child with his first wife, and he never had any aspirations of ruling Syria or being in the military or Ba’ath Party as a young man. In fact, his dream was to be an ophthalmologist, and as a young adult he trained to be an ophthalmologist in London during the 1990s. According to Bashar himself, one of the reasons ophthalmology interested him is because there was a lack of blood. While there, he was noted by fellow students and his teachers (who all knew his family background) for his humble and almost austere lifestyle (Zisser 2007, 23). Bashar was described as likable by his classmates, but a bit quiet and not especially outgoing (Zisser 2007, 23).

As much as Bashar may have dreamed of being an ophthalmologist and helping his fellow Syrians with their eye problems, duty and fate would quickly propel the young Assad to power in Syria. On January 21, 1994, Bashar’s brother Basil, who was the “heir apparent” to their father Hafez’s presidency, was killed in a car accident in the Syrian capital of Damascus (Zisser 2007, 19). Basil’s untimely death left the Assad patriarch in a quandary. Hafez had invested time and energy into making sure that Basil would be a proper replacement, but upon his son’s death a new replacement had to be found. Bashar was chosen by his father as a replacement because he was the oldest surviving son - he was actually two years older than Basil - and seen as a viable candidate because of his education and intelligence. Although he had previously shown no interest in wielding power, Bashar began to be groomed to eventually take power, and he explained the sense of duty he felt to Syria in a 2013 interview with Der Spiegel, a German publication: “It's human to love where you come from. But it is not just a question of the emotional relationship. It is also about what you, as a person, can do for your home, especially when you are in a position of authority. That becomes especially clear in times of crisis.”

At first, there were major obstacles to his assumption of power (Zisser 2007, 30). Bashar had no military experience and he was not a member of the Ba’ath Party, both of which effectively acted as the power behind the government. Also, Syria was at least nominally a republic, which meant that Bashar would have to be first “selected” (or sanctified) by the Ba’ath Party and then stand in a general election, even if that election was fraudulent. If Hafez did not follow the protocol, he would run the risk of being accused of being a potentate of the Saudi variety and risk falling in a putsch to the military and Ba’ath Party, the very people who put him in power. Thus, to counter-act any ill perception important peoples may have had about Hafez elevating Bashar as his heir apparent, Hafez placed his son in the army, where he made vital contacts and built his power base (Zisser 2007, 30).

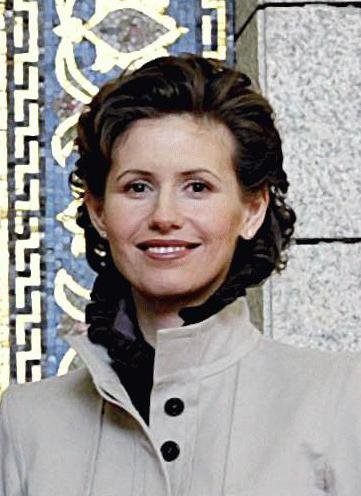

Before he became president of Syria, Bashar also became involved in his own machinations that were intended to strengthen his power base. One of the most notable steps he took was marrying a Sunni woman, Asma, which no doubt helped him appear less sectarian and appeal to the Sunni majority (though the two had a relationship before he was ever made heir apparent to the Syrian presidency) (Zisser 2007, 63). Asma’s beauty and Western roots were alluring to outsiders, as captured in a notorious profile of her done by Vogue magazine: “Asma al-Assad is glamorous, young, and very chic--the freshest and most magnetic of first ladies. Her style is not the couture-and-bling dazzle of Middle Eastern power but a deliberate lack of adornment. She's a rare combination: a thin, long-limbed beauty with a trained analytic mind who dresses with cunning understatement. Paris Match calls her ‘the element of light in a country full of shadow zones.’”

Photo of Asma al-Assad taken by Ricardo Stuckert for Agência Brasil

Despite the overtures and alliances he and his dad made, some Syrians were not happy with Bashar becoming the face of their country. Hafez’s once loyal brother, Rifaat, who was living in exile due to fallout between the two, was implicated in a plot to kill Bashar, and the Assad regime reacted by killing and imprisoning several of Rifaat’s supporters in 1999, which stopped any threat he posed to Bashar (Zisser 2007, 37).

Hafez and Rifaat (left)

With alliances made and enemies eliminated the only obstacle left in the way for Bashar to become president was his father, until June 10, 2000, when Hafez died of a heart attack at the age of 69. Right away, machinations were underway to ensure Bashar became president. First, the constitution had to be changed to allow the 34 year old Bashar to assume office because the minimum age requirement was 40 (Zisser 2007, 39). One week after his father’s death, on June 17, 2000, Bashar took the oath of loyalty that made him president of Syria after a fraudulent election was conducted, in which he won 97% of the vote (Zisser 2007, 41).

Despite the questionable election and tactics that placed him in Syria’s highest office and the obvious specter of his father’s brutally authoritarian reign, many in Syria and across the world viewed Bashar al-Assad with optimism. The optimism that many felt towards Bashar al-Assad was based on a combination of his age, educational background, and his physical looks. Bashar was viewed by many across the world as a bright young attractive leader who was married to an equally bright and attractive woman. In that regard, Asma was an important piece of the puzzle, as her Western ways not only attracted foreigners but also induced them to believe Syria might be on the path toward Westernization. As the Vogue magazine profile glowed, “The first lady works out of a small white building in a hilly, modern residential neighborhood called Muhajireen, where houses and apartments are crammed together and neighbors peer and wave from balconies. The first impression of Asma al-Assad is movement--a determined swath cut through space with a flash of red soles. Dark-brown eyes, wavy chin-length brown hair, long neck, an energetic grace. No watch, no jewelry apart from Chanel agates around her neck, not even a wedding ring, but fingernails lacquered a dark blue-green. She's breezy, conspiratorial, and fun. Her accent is English but not plummy. Despite what must be a killer IQ, she sometimes uses urban shorthand: ‘I was, like…’"

Furthermore, Bashar did not fit the standard profile of a Middle Eastern despot. For example, he did not wear a military uniform replete with medals he never won, nor was he known for fiery invective that demonized Israel or the West. He was a young man that many had high hopes for, to the extent that even before he became the president many in Syria had nicknamed him “The Hope” (Lesch 2012, 2). Much of the high hopes for Bashar no doubt were the result of his age, but much of it was also the result of his own words and actions shortly after he became president. Assad announced that the central commitments of his presidency were the following: the continuity of his father’s programs; modernization of Syrian society; more openness; and a more intellectual approach to the country’s problems (Zisser 2007, 52-56). Bashar also made attempts, at least outwardly, to de-Ba’ath the government by limiting some of the party’s powers (Zisser 2007, 73). In his own words, he suggested the direction that he intended to take the Syrian government: “Democracy is obligatory, but we must not enact the democracy of others. The Western democracies stemmed from a long history which produced leaders and traditions that created the present culture of democratic societies. We, by contrast, must adapt a democracy distinctive to us, founded on our history, culture and civilization and stemming from the needs of the society and reality in which we live.” (Zisser 2007, 41)

Although what Bashar said concerning democracy and the development of his nation may be true, it’s also easy to detect a slight tone of defiance in his words. Bashar’s idea of Syrian democracy was continuous with his father’s and essentially revolved upon the concept that what was good for the Assad family, the military, the Alawites, and the Ba’ath Party was good for Syria as a whole.

The anemic economy that Bashar inherited from his father no doubt was a factor in his current problems, but Assad also carried on many of his father’s same policies towards dissidents, which would later be a reason for many outside of Syria to oppose his regime. One of the major criticisms of the Hafez al-Assad regime was over his treatment of political rivals and dissidents. Hafez’s brutal crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood was crushing, but Bashar’s suppression of dissidents may have been more insidious, and it began to hurt his image in the eyes of the outside world. Many Syrians initially believed that Bashar was a legitimate reformer who would lead his country towards a true democracy, so shortly after Bashar’s assumption of the presidency, many politically minded Syrians began to form “cultural forums”, which were essentially groups that met at various locations (including at members’ homes) to discuss the problems facing their country and how best to solve them (Zisser 2007, 84). As the numbers of Syrians who participated in those forums grew, Assad and the Ba’ath Party carried out a three-pronged attack on these groups, who they began to view as dissidents and enemies (Zisser 2007, 89-92). First, many dissidents were physically assaulted, while others met with serious and “mysterious” accidents (Zisser 2007, 89). Next, leaders of the cultural forums were forced to obtain permits, which were often costly and nearly impossible to get, or risk fines and/or jail time (Zisser 2007, 90). Finally, writers of dissident publications were arrested (Zisser 2007, 90-92). Bashar tried to counteract any negative image he had acquired by these actions by releasing a number of other political dissidents who were imprisoned before this crackdown, but the political and social damage had been done (Zisser 2007, 93). The world began to view Bashar much as they did his father. Although Bashar was younger and more modern, his actions began to belie his true nature as a typical Middle Eastern despot.

When anti-government demonstrations broke out in early 2011, hardline elements of the Syrian government that Bashar had, to a limited extent, attempted to sideline because of their opposition to his reform efforts, were re-empowered. For these elements, repression was deemed the appropriate answer, given, at least in part, the precedent of Hama, in which Hafez was perceived as “successfully” crushing dissent through violent measures. In hindsight, however, the emergence and proliferation of social media would be a bulwark against any swift suppression of the opposition.