Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral - David Dobbs (2005)

Part II

Chapter 8. A Still Greater Sorrow

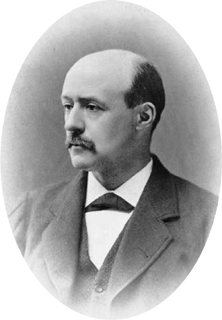

Alexander Agassiz, circa 1875

IWALKED UP and down the library with him till all was ready,” Theo Lyman wrote of Alex on Christmas Eve, the day they buried Anna.

She lay in parlor, hidden in roses and other white flowers. I turned my face to the wall and listened to the service by Dr. Peabody. It was a long way over to Forest Hills-a lovely, sunny day: her grave was … decked with branches and flowers. Alex stood at the brink, steadily, and with the tears rolling down his n8 REEF MADNESS

face, till I whispered to him to go and I would see everything finished.

The next day was only scarcely less grim. The three motherless boys opened their gifts amid likenesses of Annie that Alex had spread around the house, and they somehow bore up as Liz Cary, Theo, and Mimi tried to show some Christmas spirit. Alex was struck dumb. The tears he shed at his wife’s grave were the only ones anyone had seen him allow. “[He] can sleep and eat; and can read and write,” reported Theo; “but we cannot tell what is going on within.”

In the weeks ahead, Alex went to work most days, chipping away at the mountains of unfinished business his father left at the museum. At home on Quincy Street, where he and the boys stayed on with Liz Cary, he occupied himself rearranging bedrooms so as to have the boys’ nearer his. For a time he helped Cary with a “life and letters” biography of Louis, but he soon let her take that over; with Louis’s piles of unfinished correspondence, projects, and papers to deal with, his life already held too much of his father. He spent much of January responding to the many acquaintances and friends who had sent their condolences on Louis’s death. Most of them had written with out knowing that Annie had died too. Among these were Ernst Haeckel, the Naturphilosopher and Darwin champion whom Alex had befriended in Europe four years before. A few months later, Haeckel would publish a vicious dismissal of Louis’s work, calling him a charlatan and a plagiarist, provoking Alex to break off relations permanently. But at this point Alex could still confide in the man with whom he had long corresponded about embryology:

Your kind note written soon after father’s death finds me over whelmed by a still greater sorrow which has fallen upon me like a thunder-clap out of a clear sky. I had the misfortune a few days after fathers death to lose my wife… [Now] all seems of little consequence and I am utterly unable to get reconciled to an existence which is well-nigh intolerable …; at present I can find no incentive for anything and I can only hope that in the course of time my interest in my children and in my work may ultimately reconcile me to a sort of passive life.

While Alexander Agassiz hardly lived a passive life after Louis and Anna died, neither did he ever fully recover from this double blow. Much of the time he pressed forward out of duty, staying home for the boys as long as he could stand it and then, when his grief grew too huge, fleeing, leaving the boys with Cary His eyes, which during his marriage had lost their boyish wariness to a sure if gruff confidence, took on a more confirmed darkness. “Alex is drawing in, and hiding his grief,” wrote Theo, “[but] it tells on him, as you see in his great, sad black eyes, that sometimes wander as if they might see what they sought.” This look would remain all his life.

He found the first year nearly unbearable. The restless depression he suffered would today be recognized as mortally dangerous; it was all he could do, he told friends, to sit still, yet if he attempted too much, he collapsed in exhaustion and despair. The Quincy Street house, even the voices of his sons haunted him. In February he escaped, leaving the boys with Cary and going with Theo and Mimi on a six-week, six-thousand-mile trip down the coast to Florida and New Orleans and then up the Mississippi and Ohio to Cincinnati. When they returned, his grief seemed less acute, and for a time he applied himself energetically at the museum, finishing work on some of his father’s publications, cleaning up the accounts and operations, proofing the final volume of Revision of the Echini.

Then he made a mistake. He tried to run the summer school that Louis had started the year before at Penikese Island, just off the Massachusetts coast. The school was an invigorating thrill for Louis but a stone for Alexander. Theo Lyman, out on the island to teach and help Alex run the place, entered the office one day to find Alex bawling uncontrollably. “It was one of those moments when the load was too heavy,” wrote Theo. “He sat in his chamber and cried with out control; and seemed like a man who had lost much blood.” Theo took him to Brookline to rest. Every morning when Alex woke, Theo reported, “his hands were numb.”

Alex’s own appraisal was equally blunt. “I was obliged to drop Penikese,” he wrote a friend. “It broke me down completely. … As long as I am idle I flourish, but the least work unnerves me completely so that I seem to have no control over myself. If matters do not mend I must pack up my traps and go off for a few months for an entire change of scene.”

Matters did not mend. The one piece of positive family news was that Mimi Lyman was pregnant. But while Alex was glad for his friends, the solace that the new pregnancy offered them, still grieving after the loss of their daughter, only sharpened his own misery. As Mimi’s November due date and the anniversary of Alex’s double loss neared, he turned again to the anodyne of travel. This time he would go to the Andes and Lake Titicaca. His ostensible purposes were to examine copper mines, gather artifacts for Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Ethnology, and do some zoological collecting. Mostly however, he would simply try to stay a step ahead of his sorrow.

It worked for the most part, though the early weeks were rough. On the anniversary of Anna’s death, having just arrived in Peru and not yet traveling in earnest, he broke down completely, according to his son George in Letters and Recollections, penning a “beautiful and pathetic letter” of grief to Liz Cary* Writing it seemed to bring relief, however, for the next day Alex composed four pages of good travel narrative to Theo Lyman with no mention of heartache. A few days later he set off on his long overland travels.

For several weeks he covered new terrain rapidly enough to divert himself. Though his destination was Titicaca, he was in no hurry to get there, for the whole point was to move. An assistant curator from the museum, S. W. Garman, had come along to help at Titicaca, and Alex now sent him ahead by train-an often vertiginous three-hundred-mile course through the Andes-while he took a more meandering route by horse. Alexander had always loved to ride, and he now rode for most of several weeks, covering up to forty miles a day and getting fit and tough and tired enough to drop straight to sleep each night. Usually he stayed with new friends, for he found that a single letter of introduction (such as those he carried to the managers of the mines he visited, most of them Europeans) would create a running chain of new invitations. He thus generally traveled with good local advice and often a guide provided by his hosts.

Having spent his life in verdant climes, he found the pampas stark. His letters show a knack for landscape description that surfaces only occasionally in his professional writing:

What a pretty country this coast range would be were it only green, but you see only here and there a few green bushes; to be sure they say that in spring it is covered with wild flowers, but as in California it lasts but a very short time. Some of the trans verse valleys, where a little water still winds its way among the pebbles, are masses of green, and give you an idea of what this country might be with irrigation. There must have been water here in plenty in olden times, for the town of Ovalle and the terminus of the railroad from Coquimbo are placed in the broad bed of an ancient river, and high above the town rise the old terraces over two hundred feet high, through which the for merriver once cut its way and has now left the huge masses of pebbles and cobble stones which compose the surrounding hills. You do not see, even in the Connecticut Valley, better river terraces than found here, only here they are due to the gradual rising of the whole of the Chile coast, so plainly seen by this sort of formation, and by the old beaches high above the present level which you find all along the coast.

Other areas, such as the Atacama Desert, a great, arid bowl in Chile, were downright surreal. “It is exactly like riding over a dried-up caldron bottom filled with salt,” he wrote home, “which is left in huge cakes a couple of feet thick, with horns of salt in all possible shapes sticking out in all directions, through which you wind your way. … As you ride along you are nearly suffocated with this salt dust getting into your eyes and ears and mouth.” East of the desert, low green hills gave “a very fine panorama” of the mountains cut by deep canyons marking the paths of dead rivers.

“The bleakness of the scene, the utter desolation and waste of the prospect, I cannot describe, [and] not a living thing did I see,” he wrote Cary. But while the land’s bareness intimidated, it also revealed the geological puzzles of the steep, sharp-crested cordillera. Like others before him, Alexander could not resist the riddles posed by the Andes’ exposed history. The raised shorelines and river bottoms fairly shouted of geologic uplift, as did the marine fossils everywhere- seashells on the shores of mountain lakes, coral embedded in ledges at three thousand feet. It was the most interesting land he’d ever encountered. “I wish,” he lamented, “I could have time to remain here to study [it].”

Eventually, having wound over large parts of Peru and Chile, he took a train to Titicaca. The world’s highest navigable lake, some 125 miles long and 50 wide (about half the size of Lake Erie), 3,200 miles square, and averaging several hundred feet deep, Titicaca sits in the northern part of the altiplano, a broad, terraced plateau between two of the Andes’ tallest ranges. It drains an immense area. Twenty-five rivers flow into it, yet the strong sun and dry wind lift so much water off the surface that the sole river exiting drains only 5 percent as much water as enters the lake. The rest evaporates. The altiplano, still rising, has rearranged itself in tectonic heaves several times just within the last few millennia. Though the lake once spread far wider than it does today, on its bottom rest Incan ruins built only a few thousand years ago, when the topography and climate left them dry.

Alex was interested in these ruins as well as in what life occupied the lake. But when he caught up with Garman, the young curator had discovered only three fish species in weeks of work, bringing the lake’s total fish species count to six; as in many other high lakes or polar waters, a few fish species ruled all. Garman fared better with mollusks and crustacea, pleasing his boss, and captured some immense frogs and “an excellent collection” of birds. (He did not collect any local cattle, even though the cattle, descendents of cows brought by the Spaniards, had by now developed some unusual pseudoamphibious habits: In the dry season, finding little on the arid shores, the cows and bulls waded up to their flanks and, mooselike, dunked their heads to pull water weeds.)

Alex, arriving after his weeks of riding horseback and train, checked in with Garman for a couple of days and sent him back out on the lake for more dredging and collecting. Then he set off in the Yavari, a small steamer provided by the Peruvian government, to survey the lake and do some dredging of his own. He looked mainly for antiquities and Incan artifacts, a novel use of the dredge that brought him few treasures. He did better bargaining with people for the old things they had in their houses. The straightforward, efficient Agassiz met intense frustration when some object that he spotted in a corner pile or “kicking about in all directions,” as he complained to Cary, “much as [in] George and Max’s play-room,” assumed immense value the instant he showed interest in it. Bargaining maddened him. His cash usually prevailed, of course, and he eventually brought back an impressive trove. In the practice of the day he also dug up a few Indian graves for the mummies and the fishing, hunting, and house hold implements buried with them.

When not on the boat or traveling the surrounding countryside, he stayed in a railcar that the local mining engineers had outfitted with a tiny kitchen, dining room, and parlor, and in which they granted him one of the five bunks. Here, because he was tired, or because he was at his final planned stop, or perhaps simply because he stopped moving, the gloom caught up with him. Writing Theo to congratulate him on the birth of his son two months before, he despaired of finding the sort of hope that Theo now possessed.

I wish I could see the youngster and his parents and look in upon your happiness for a moment. You can start life again now with as bright prospects for the future as any one could wish and I hope you and Mimi will have all the happiness you deserve. I find it harder and harder to face my prospects. It is all well enough when hard at work or when I have to make an effort to keep up my spirits as I must do constantly while staying with people who have been so kind to me …, but when the necessity of this has passed I am left with nothing to distract me [and] it seems to me as if I could not endure. Time does not make any difference and all I can do is try and distract myself with novelties. As for settling down in any one spot I have not the heart and the prospect of staying proudly at home seems unbearable. I know it is not right to the boys but it is stronger than I am at present and I must keep on the move for a while at least.

He kept on the move for a few more weeks, poking around the towns near Titicaca for more artifacts. By early March he felt it time he got home. He sent Garman away with the zoological and ethno graphic collections, then retraced his steps out of the Andes. From Callao he sailed along the coast to Panama, where he visited old friends, then trained across the isthmus and steamed across the Caribbean and up the seacoast to New York. Other than being happy to see his boys, he did not pretend to be glad to return. His past seemed all but obliterated; what remained of it haunted him; and he saw nothing to draw him forward. Yet in fact he had already encountered his future amid the Andes’ arid crenulations. It lay in the coral embedded there, and in the trail of a man who had come before him.

*George did not print or excerpt the letter and seems to have destroyed it, for it is in none of the archives. This was not the only loss to such housecleaning. In Alex’s letterbooks-the thin-leaved letterpress volumes in which he recorded copies of all his outgoing correspondence-the four pages spanning December 1873 to early January 1874 are among a dozen or so that someone razored out. In addition, Alex wrote some letters of a more personal nature- there’s no way to know how many-without copying them at all.