Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral - David Dobbs (2005)

Part I

Chapter 4. Cambridge

I

ARRIVING IN New York in June 1849, thirteen-year-old Alexander Agassiz entered a world sharply different from the one he had left. Though Boston, to which Louis immediately took him, resembled European cities more than did most American towns (Louis generously likened it to Paris and London), it remained a far cry from Freiburg. And Alex, shy to start with, knowing hardly a word of English, must have felt the language barrier keenly.

He found his father, however, glowing from his seduction of his new country. For Louis Agassiz had conquered the United States faster and more thoroughly than perhaps any foreigner ever had. He loomed large almost from the instant he arrived, and while he made a sensational impact, it proved lasting, exerting an intellectual and cultural influence well beyond his initial fame and beyond even his death a quarter century later. Much of the initial fervor was created by his brilliance, eloquence, and charm. But his wider, more enduring impact spread not simply because he was irresistible, but because he offered a set of ideas for which his new country was ripe. His reconciliation of Christianity and science stood at the center of this appeal. But equally vital was that his particular marriage of learning and spirit-his elegant synthesis of the scholarly world of facts and ideas with a Whitmanesque sensual attentiveness-suggested a way for his vibrant but insecure adopted nation to establish its intellectual heritage. As a result, his appeal overran bounds of fashion, politics, interest, and time. His contemporary admirers included virtually all of his scientific and intellectual peers, the country’s financial and social elite, and cultural luminaries ranging from Henry Wads-worth Longfellow to Henry David Thoreau. Among later generations, his devotees spanned the spectrum from Teddy Roosevelt to Ezra Pound and included virtually every naturalist trained in the United States. These admirers saw in Louis something vitally American. As William James (who traveled to Brazil with Louis as a Harvard undergrad and became friends with Alex) wrote in a moving and insightful tribute almost twenty-five years after Louis’s death, no American since Benjamin Franklin had so embodied the country’s spirit or captured its imagination.

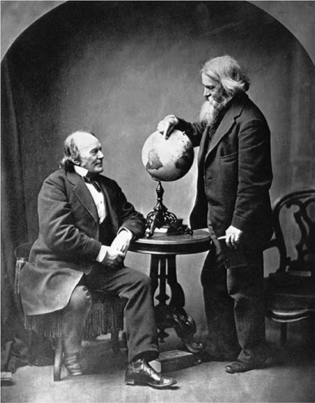

Louis Agassiz with his friend and ally Benjamin Peirce, the Harvard mathematician. Peirce is pointing out the location of Cambridge, Massachusetts, on the globe. In the 1850s, the two men were unchallenged in the world of American science.

2

Louis’s American renown actually preceded him. The textile magnate and Harvard supporter John Amory Lowell, founder of the Lowell Institute and its already famous lecture series, first heard of Louis in detail in 1842 when Charles Lyell, in Boston to give that year’s Lowell Lectures, gushed about Louis’s eloquence and agility of mind. Bolstered with that and other recommendations (a composite portrait suggesting a gregarious fusion of Cuvier and Lyell), Lowell invited Louis to give the lectures over the winter of 1846-1847, then excited his many friends in the national press into trumpeting Louis’s arrival.

The accolades grew as Louis spent his first month in the United States visiting universities and science centers in New Haven, Albany, New York City, Princeton, Philadelphia, and Washington. He completely seduced the country’s intelligentsia. He seemed to know the particulars of almost everything going on in all current natural science and could readily discuss the philosophical questions raised. He showed a flattering curiosity about everyone’s work and seemed instantly to grasp the possibilities, problems, and fascinations of every scientific inquiry-and often offered observations that expanded the investigator’s horizons. Benjamin Silliman, Jr., a second-generation Yale chemistry professor who knew pretty much everyone in American science, offered a typical effusion after Louis’s first visit to New Haven:

He is full of knowledge on all subjects of science, imparts it in the most graceful and modest manner and has, if possible, more of bonhomie than of knowledge. He has a more minute knowledge of his subject and at the same time a more wonderful generalizing power and philosophical tone than any man I have ever met. … It is not yet agreed whether the Ladies more liked the Man or the Gentlemen the Philosopher. 2

Louis cemented this impression of amiable savant with the Low ell Lecture series he gave beginning that December. By that time the talks were so keenly anticipated that the organizers offered a second lecture most days, and Louis packed the house-some five thousand seats-again and again. The lectures, which he titled “The Plan of Creation in the Animal Kingdom,” elaborated Cuvier’s vision of nature as divine design, but with a panache that only Louis could bring. In talks rich with facts, oddities, and charming asides, he described how the preceding century’s zoological discoveries had revealed a natural order so intricately patterned that only a supreme intelligence could have created it. Some of nature’s patterns, he explained, announced themselves-witness the prevalence of symmetry in body type or other major traits shared by closely related species. Other patterns revealed themselves only through close observation-the way developing embryos of advanced species, for instance, seemed to mimic successively the forms of “lower” species, so that a chimpanzee fetus resembled first a fish and then a pig before coming to look something like a chimp. He chose examples so astutely and described them so evocatively that while a textile worker could understand them, the country’s most advanced scientists, such as the botanist Asa Gray or Benjamin Silliman, Jr., learned some thing new.

He described the discovery of unexpected and often beautiful patterns in highly different life-forms, such as spiral structures found in both plants and animals, food-catching tentacles found in sea animals and terrestrial plants, and the radiate patterns found in both flowers and marine invertebrates. About the time he had everyone slack-jawed in wonder, he would provide comic relief by explaining how even the apparent breaks from this pattern-what he called “God’s leetle jokes,” such as the turtle or the narwhal-fit into the plan. Working without notes, he delivered all this with great animation and humor. When he was stumped for the right word in English (fumbling always oh so endearingly through a few candidates), he would draw on the blackboard, describing as he went.

Such a vast, complicated, highly structured scheme, he said, could only be the work of God. What else could account for such variety of form unified by so many patterns? True, some scientists and philosophers had suggested that some undocumented dynamic called evolution, or transmutation, might play a hand. But evolution was not only unfounded (no one had ever shown how one species could change to another); it was unneeded, for divine design could explain all of nature’s wonderful diversity. A species did not emerge from some mysterious transmuting force. It rose, said Louis, as “a thought of God.”

Thus Louis Agassiz sold a view of nature that seemed at once enticingly progressive and safely devout. Like the Covariant taxonomy from which it sprang, Louis’s plan of creation seemed to push science forward without threatening prevailing religious views about the world’s genesis. He appeared to resolve the tension between science and religion that had haunted scientists since Copernicus. Here was a rigorous science that not only tolerated belief in God but actually required it.

It was an alluring vision. Louis made it even more so by insisting that the observant amateur could discover these patterns as readily as the learned scholar. “Study nature, not books,” he urged his audience, espousing a seductively egalitarian notion of what it takes to master a discipline. Like a music teacher who kindly insists that feeling the music is the main thing-never mind all this theory, technique, and note reading-he appealed both to the democratic spirit and to the romantic notion that formal education is less important than enthusiastic application.

Louis’s elevation of nature above books ignored the exhaustive formal study underlying his own knowledge. It also clashed with an elitism that showed in his chubbiness and his later development of exclusive scientific societies such as the National Academy of Sciences. Yet it stood in perfect accord with his romanticism. Perhaps because he discovered his love of biology tramping in fields, Louis had long lectured and led field trips not just for advanced students but for dedicated amateurs, especially teachers and children. He insisted that any smart person could become a proficient naturalist. Now, as he lectured before large lay audiences as well as professionals painfully mindful that they lacked the institutional resources that Louis had tapped in Europe, both his message and his manner-his affable approachability; his encouragement of amateurs; even his self-effacing, out-loud search for the right word, as if showing the thinness of his own education-insisted that an elastic mind, a sharp eye, and direct contact with nature ranked as the natural scientist’s most vital assets. As his years in America strengthened this belief, it came to imbue every aspect of his teaching. He expressed it most notably in his sink-or-swim introduction to comparative anatomy, in which he would give a new student a strange specimen, usually from the sea, to examine for several days during which the student was to observe everything possible but never consult a book. He sometimes forbade books from dissection rooms altogether. The truth lay not in books or inherited knowledge; it stood before you, a work of God.

For a country eager to claim intellectual parity with Europe but keenly aware that it lacked a comparable intellectual history or institutional infrastructure, these ideas held immeasurable attraction- the more so, of course, for coming from one of Europe’s top scientists.

So it was that Louis Agassiz satisfied America’s hunger for some one to raise the torch that Franklin and Jefferson had once carried- a learned figure of international stature who was a peer to Europe’s best, yet distinctly and unapologetically American in spirit. Strange that a new immigrant should be the one to fill this role. Yet Louis Agassiz’s immediate understanding and embrace of America’s energy and independence suited him for the task, while his European training ensured credibility.

Louis could thus resolve, as perhaps no one else could (and as enthusiastically as anyone could hope), Americans’ mixed feelings regarding European learning. On one hand, as many observers (most famously Alexis de Tocqueville) noted, America in the early 1800s exuded confidence that its homegrown vigor could best European sophistication in any arena, military, political, economic, or cultural. Yet anyone paying attention recognized that America lagged Europe horribly in scholarly and scientific pursuits and institutions. Virtually all leading American scholars and scientists of the time went to Europe for their advanced training, and many native observers bemoaned the lack of any vital American intellectual or cultural spirit. Henry Adams, for instance, complained that Americans “had no time for thought; they saw, and could see, nothing beyond their day’s work; … their attitude to the universe outside them was that of the deep-sea fish.” Americans’ appreciation of beauty and culture, he felt, was succinctly expressed in Grant’s lament that Venice would be a nice city if it were drained. Adams and others blamed this cultural myopia on the industrial age’s growing materialism. A more prickly assessment came from the Spanish-born Harvard philosopher George Santayana, who found the American imagination not merely suppressed but geriatrically sterile. The established strain of American culture at the time-the Euro-imitative arts and sciences against which Whitman, Melville, Emerson, and others rebelled- Santayana saw as a “harvest of leaves” by a culture holding “an expurgated and barren conception of life … without native roots [or] fresh sap.”

“[Even when Americans] made attempts to rejuvenate their minds by broaching native subjects,” Santayana wrote, “the inspiration did not seem much more American than that of Swift or … Chateaubriand… If anyone, like Walt Whitman, penetrated to the feelings and images which the American scene was able to breed out of itself, … he misrepresented the minds of cultivated Americans; in them the head as yet did not belong to the trunk.”

Louis’s vision of nature study, however, presented a way to connect head, trunk, and soil. Drawing on native materials with energy optimism, and initiative, naturalists both amateur and professional could create a homegrown alternative to stale high culture and debased mass culture while making a liberating asset of the country’s lack of educational infrastructure. It was a neat trick, applying to science the celebration of endemic American energy that found literary voice in Whitman. Louis sang a song of scientific self

Everyone ate it up-even future opponents like the Yale geologist James Dwight Dana and Harvard’s Asa Gray. Though these men knew perfectly well that book learning was as vital as observation, they were enthralled by Agassiz’s stunning memory, quickness of mind, and unrivaled power to rouse interest in natural science. Gray who accompanied Agassiz on his initial tour down the coast, wrote a friend that Agassiz “charms all, both popular and scientific” and was “as excellent a man as he is a superb naturalist.” The man who would later battle Agassiz over Darwin’s theory of natural selection wrote now that his lectures on embryology showed clearly that nature was formed by something other than just disinterested physical processes.

Reviews like this spurred tremendous demand for Agassiz’s lec- tures. He had originally planned to give the Lowell Lectures and then tour the continent researching its natural history (thus fulfilling his duty to King Ferdinand). But even before he finished the Lowell series, he was getting offers from other institutions vying to land what Jacob Bailey the naturalist at West Point, called “the big fish Agassiz.” A bidding frenzy ensued, and Louis soon abandoned his plans for King Ferdinand’s continental survey and concentrated on lecturing. In his first year in the United States, he earned more than eight thou sand dollars-a huge sum at the time, more than he’d made in the previous decade in Europe-and was able to pay off all the debts he’d run up over fifteen years at Neuchâtel. Celebrity paid well.

Louis Agassiz, of course, was not merely famous. He was a genuinely distinguished scientist with a singular ability to inspire. This was not lost on John Lowell and the other members of Harvard University’s corporation (its equivalent of a board of trustees). The university had been hoping to establish a school of science, and here arrived the perfect man to lead it-dynamic, energetic, internation ally renowned, and able to raise money effortlessly. Lowell, inquiring gently with Louis and getting a warm response, convinced a fellow textile magnate, Abbott Lawrence, to underwrite a new science school. The Lawrence Scientific School (later absorbed into Harvard’s school of arts and sciences) was thus created in 1847, and Louis became its first professor and effective director.

Eighteen months into his American tenure, then, Louis Agassiz had achieved goals of which he had long dreamed but so far fallen short: He had a prestigious and well-paid teaching position at a major institution; the ability to earn almost unlimited amounts of money and adulation; and near official status as his adoptive country’s first naturalist.

3

When Alex arrived to join him, he found his father riding the headiest surge of his American success. Louis was also elated over the woman he introduced to Alex as his stepmother-to-be, Elizabeth Cabot Cary

Well educated, musical, bilingual, attractive, warm hearted, and twenty-seven years old (as near in age to Alex as to Louis), Liz Cary was about the best thing that could have happened not just to Louis but to Alex. By all accounts she took Alex to heart immediately, and he, grateful after his recent trials for such an unequivocal commitment, remained dedicated to her all his life. In later years he called her his best friend as well as his mother. As for Louis, marrying Liz Cary furnished private stability and happiness for himself and his children and secured his acceptance into the highest layers of Boston society. For Elizabeth Cabot Cary was born of the Cabot family, one of the richest and most established of the oft-mingled clans (Cabots, Lowells, Feltons Shaws, and others) who dominated Boston finance and society.

Liz Cary also possessed astonishing grace, intelligence, empathy strength, and energy, and she managed to enhance and enjoy Louis’s ambitions while curbing his domestic excesses. She greatly stabilized (one is tempted to say civilized) the home in which Alex lived. Upon his son’s arrival, Louis’s house held a menagerie that included snakes, an eagle, and a bear that was a gift from Henry Thoreau. Presumably a symbol of nature’s noble simplicity, the bear simplified nothing, though it did offer unpredictable entertainment, as when during a dinner party it slipped its chains in the basement, raided the wine cask, and stumbled upstairs to disrupt the party. (It soon graced the dissecting table.) When Cary moved in, the animals and all of Louis’s aides save Burkhardt moved out, and Alex, soon joined by his sisters, settled into the best-regulated home they ever had. (Some animals eluded immediate capture. Several weeks after moving in, Cary found a fugitive snake in one of her shoes. Louis, hearing her shout of protest, said he was wondering where that snake had got to.)

Even sans animaux, the place remained busy, for Cary and Agas-siz, a sort of elite dream couple, became a node of Cambridge and Boston’s social world. With Cary’s help, Louis had conquered Brahmin Boston as thoroughly as he had Harvard. Ralph Waldo Emerson, in for a Boston visit from his own web in Concord, had heard enough of Louis from Thoreau and others that he knew him at first sight: “I saw in the cars a broad-featured, unctuous man, fat and plenteous as some successful politician, and pretty soon divined it must be the foreign professor who has had so marked a success in all our scientific and social circles, having established unquestionable leadership in them all; and it was Agassiz.”

4

Emerson soon joined the circle, becoming part of Louis’s elite Saturday Club. On other nights, Cabots, Feltons, and Lowells came for dinner, and the place often swarmed with less formal visitors. Alex sometimes came home from school to find his father jawing with the great mathematician Benjamin Peirce, who lived across Quincy Street from Agassiz and became a close friend. Their bond seemed one of opposites. Peirce was a ferociously unapologetic intellectual elitist (he once delighted in being publicly called a nabob), a notoriously opaque lecturer, and a brilliant mathematician, while Louis espoused intellectual egalitarianism, lectured with singular lucidity and could scarcely add. But they agreed that the universe was a divine creation, that it could be understood by those few who could perceive the rules of God’s order, and that they ranked high among those few. Peirce, amused that his computationally challenged friend had a mathematically talented son, would often conjure some math puzzle for Alex. Alex usually solved it, which suggests both his intelligence and Peirce’s feelings for him, for Peirce could stump anyone and usually chose to. Alex would witness an even more unpredictable mixture of lucidity and obscurity when the Saturday Club gathered, with Agassiz and Peirce joined by John Lowell, Longfel low, Emerson, and other luminaries who would talk deep into the night.

In this setting Alex began a part of his life more peaceful and productive, though hardly boring or routine. Once past his initial shy ness and difficulties with English, he quickly made friends with his fellow students and the children of Cary’s friends. In winter he liked to skate, and in summers he accompanied his father, stepmother, and sisters to Nahant, an island northeast of Boston where the Cabots and other blue bloods summered. There he developed a love of marine biology that grew all his life. He and his sisters sometimes accompanied their father and Cary on collecting or lecturing trips farther a field. In his first years in the United States, Alex traveled up and down the eastern seaboard; to the Gulf Coast; to the Florida Keys for the 1851 reef study; to South Carolina the following two winters when his father had lecturing stints in Charleston; and to many universities and scientific institutions between Boston and Washington,

D.C. By the time he was halfway through college, he was an accomplished field worker and had met most of the country’s scientific elite.

Alex took great advantage of the opportunities this new world offered, resisting distraction and showing remarkable resilience and concentration. Already he could work as few others could. The youth was showing the characteristics that would distinguish the man: “The thoroughness and ease with which he worked, his great reserve, his sudden explosions of indignation, his quiet and entire devotion to those he loved, his occasional outbursts of mirth, as delightful as they were unexpected, his unfailing charm-all these belonged to the Swiss boy no less than to the scientific man of cosmopolitan friendship and fame.”

Enrolling at Cambridge High School soon after he arrived, he graduated two years later, in spring 1851, at fifteen. That fall he entered Harvard. He excelled in all sciences and in math, having more luck than most in following Peirce’s lectures. Yet while he spoke five languages, he showed little interest in studying any of them, and he assiduously avoided philosophy. Like Peirce, who loved math because it was the most rigorous instrument for testing theories, Alex sought knowledge where it could be found and confirmed with most certainty. As his son would later phrase it, “He devoted himself to the knowable, and left groping among the intangibles to others.”

We can only wonder how much of this agnosticism was a reaction to his father’s promiscuous theorizing. Each side of Alex’s family had harboured doers as well as thinkers (Cécile had a second brother who was a mining engineer, and Louis’s brother was a merchant), so perhaps Alex merely inherited a practical bent. Yet it invites speculation that a youth so exposed to philosophical inquiry should seem averse to it. His uncle Alexander, Alex’s most substantial intellectual influence in the years before he came to America, was an adherent of Naturphilosophie, and Louis, though claiming a strict empiricism, spun elaborate speculative structures from his findings and talked to no end of philosophical matters.

Alex steered decidedly clear of all this, even as an undergraduate, when such musings come most naturally. This hard-nosed literal-mindedness, which he would retain all his life, fit firmly into an apparent abjuration of his father’s excesses. Where Louis was loud, impulsive, expansive, and distractible, Alex was quiet, steady, held his cards close, and worked with a diligence-actually finishing things-that his father had sustained only briefly and only in his youth. Perhaps when one has a father as flamboyant as Louis Agassiz, the best rebellion is quiet conservatism. Or perhaps Alex simply saw the trouble Louis’s extravagance created and chose a more controlled path. He had certainly suffered enough shocks riding Louis’s.

In any case, Alex approached his schoolwork with remarkable energy and discipline. While not the bon vivant his father was, he had a quieter sort of charm beneath his subdued, acutely attentive demeanor. One friend he made in South Carolina the winter of 1851-1852, a young woman four years older than he (twenty to his six teen), recalled later that “he was so different from other boys, and so delightful, a most charming boy-just at the age when boys are so seldom charming.” Though reserved, he was confident socially. Having long produced small plays with his sisters, he joined Harvard’s Hasty Pudding theatrical club, and he rowed bow on a famed crew that also included Charles William Eliot, who as president of the university from 1869 to 1909 would become one of the most important figures in American higher education. (At only medium height and around 140 pounds, Alex would seem an unlikely oars man, but he had impressive physical strength all his life.)

Living in the big Quincy Street house with his family, going to class across the street with his father and his father’s colleagues during the day, Alex did not exactly move beyond his father’s sphere while attending college, nor beyond the complications arising from Louis’s chronic overextension. As his college years ended, Alex found himself teaching in a girls’ prep school that Liz Cary had founded. Cary started the school partly out of a strong interest in education (she later became Radcliff College’s first president) but also because Louis, even with his new salary and lucrative speaking calendar, was again spending more than he earned. Cary, determined to provide a household income independent of Louis’s, set up the Agassiz Girls’ School and recruited Alex to teach there. He dutifully took the job even while he studied chemistry briefly and then reenrol led in the Lawrence Scientific School for another graduate degree, this one in natural history. For the next two years, he fit a half-time teaching position at the girls’ school amid his studies.

Many twenty-year-old men would relish holding forth before rooms full of bright young women, but Alex hated it. Unlike his father, he found teaching neither easy nor enjoyable. In fact he seemed increasingly resistant to the charms of both academe and natural history as professions. He told his close friend and classmate Theodore Lyman that he had entered engineering school because he didn’t want to be a poor biologist or have to teach all his life. Now, as he finished his natural history degree, that sense of entrapment seemed to resurface: He had his degree (three, in fact-an undergrad degree in zoology and master’s equivalents in engineering and natural history) but faced the sort of under funded, overextended existence he so hated seeing in his father. He was also in love, having fallen for one of his students, Anna Russell, the daughter of blue-blooded family friends. He wanted to marry her, but the thought of doing so and then staying on at the museum and making ends meet by teaching, either at the girls’ school or at his father’s school, felt constricting.

Louis set up an escape route: Alexander Dallas Bach, a good friend of his who was the director of the U.S. Coast Survey, happened to need a capable, sea-legged scientist and engineer to help survey the Pacific Northwest coast. It was a connection job, but Alex, educated in geology, oceanography, and engineering and an experienced coastal cruiser, was superbly qualified. The position sounded promising. Bache, emphasizing the military and commercial advantages of well-surveyed waters, had drawn massive government resources to the survey, and its work was highly regarded. But the cruise Alex went on during the fall of 1859 suffered such bad weather, and Alex so resented the bureaucratic inefficiencies of a government operation, that when cold weather halted operations for a time he took a leave rather than seek another immediate assignment.

In San Francisco, waiting for a boat to start the long trip home via Panama (which still had to be crossed overland), he spent almost a month catching, drawing, and cataloging perch and medusae. He became so absorbed that he didn’t want to leave, and indeed he did not leave until he had written dozens of pages of description to “moncher papa” and a monograph on West Coast perch. Then, perhaps deterred by the thought of returning to Boston’s winter, he accepted an invitation from the superintendent of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, whom he had befriended on his westward passage over the isthmus, to be his guest in Acapulco and Panama. In both places he did yet more collecting and wrote more long letters to Louis, scores of pages of lovely pen work and maps and drawings of sea creatures-medusae, crabs, crustaceans, sea worms and sea slugs, shrimp-each numbered and tied to a description at letter’s end. They were casual, newsy letters home, but they were also natural history papers almost ready for publication, and he in fact later revised and published several.

His Coastal Survey job, meanwhile, remained available. But as the weeks passed, the job held less attraction. Though the work was sometimes exciting, the pay was poor, and he missed his fiancée. As he collected, cataloged, drew, and described, it became clear that engineering, whatever its practical and pecuniary attractions, would never hold him the way biology did. Like a boat coming around, his thoughts and plans turned toward home, and more seriously toward marriage.

The only problem was money. Anna Russell came from yet another rich merchant family, but she and Alex had agreed they should live independently. She had even reduced her spending in his absence, as if in preparation for a naturalist’s budget. But though she was willing to sacrifice some comfort, neither she nor Alex was ready to live penniless. He needed a salary.

Here Theodore Lyman stepped in. Like many of the friends Alex had made through family and school, Lyman was rich, and as a fellow zoologist and graduate of the Scientific School he saw natural history as a vital enterprise. He also felt (as Henry Adams would echo years later) that Alex was the best of the class both at Harvard and the Scientific School. It bothered him that a lack of funds should keep his gifted friend from pursuing science. Lyman knew of Louis’s chronic, maddening overextension and his erratic ways, and he felt sad to see how Alex suffered them. So he proposed a solution. Louis Agassiz had finally talked Harvard, along with the Massachusetts legislature and several private donors (including the Lyman family), into financing the establishment of a permanent museum for the Scientific School’s growing collections. Construction on the Museum of Comparative Zoology had in fact begun while Alex was away. This new museum would need curators to organize its collections, and Lyman had already volunteered to serve as a curator of mollusks. Facing an arduous task (for Louis had acquired many, many mollusks), Lyman convinced Alex to let him fund another curatorial position so that Alex could work alongside him. Lyman put up fifteen hundred dollars a year (the sum Harvard had offered Louis just ten years before). This was not a plush salary and would require that Alex (and Russell, after they married) live with Louis and Liz Cary for a while to make ends meet. But it was a start.