Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral - David Dobbs (2005)

Part II

Chapter 13. “A Conspiracy of Silence”

I

IN 1847, when Alex was twelve and collecting beetles and nursing his mother in Freiburg and Darwin was thirty-eight and studying barnacles, George John Douglas Campbell, twenty-four, inherited the title he would thereafter prefer, the eighth Duke of Argyll. Camp bell also inherited a castle and 170,000 Highland acres. The land included some of the United Kingdom’s most intriguing geology. The Duke, intelligent and energetic, was soon spending considerable time studying it. Inspired to a gentleman’s life of science, he joined the Royal Society of London in 1851 (the same year as Huxley), and for the rest of his life he fit an amateur scientific career around distinguished service as a politician and diplomat. Appointed to several cabinets and as secretary of state for India, he was active in the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Murray’s home group, to which he was once elected president. He was a familiar figure amid both the London scientific establishment of Buckland, Lyell, and Darwin and the Scottish scientific community that included Thomson and Murray.

The Duke was proud to be a high figure in the world’s dominant power, and while he held liberal (if not exactly egalitarian) sentiments in governmental matters, he was conservative as a scientist. A catastrophist, he wanted no part of the Lillian uniformitarianism that emerged in the 1830s, and he despised Darwin’s theory of evolution and the seemingly atheistic positivist philosophies it epitomized.

He did not espouse the special creationism of Louis Agassiz, but he believed that since God created the world, the study of nature should at least implicitly be the study of God’s work. To reduce nature’s phenomena to arbitrary processes, to deny its workings any sense of purpose, and to sever facts from values was to cast God away from both the world and humankind.

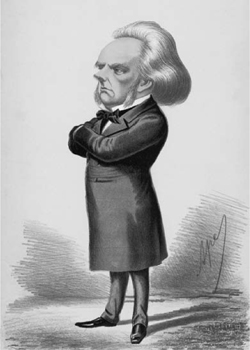

George John Douglas Campbell, the eighth Duke of Argyll in an 1869 cartoon. Campbell’s entry into the coral reef debate a decade later brought it a prominence no one had expected.

These attitudes were not uncommon among Victorians. Indeed, their prevalence was what made Darwinism so controversial. But the Duke articulated them with uncommon energy and skill, writing often and eloquently on science, education, religion, and philosophy. He clashed constantly with Thomas Huxley. If Huxley was Darwin’s bulldog, the Duke was the terrier who plagued Darwin by forever popping out of hedges to yap and snap. Huxley and the Duke first tangled in the early 1860s, and their dogfights ran clear into the 1890s. Huxley’s side won the war, of course, but his scraps with the Duke cut scars that ached for at least another generation. As late as 1918, Leonard Huxley, Thomas’s son, called the Duke (safely dead by then) “a polemical upholder of ideas left stranded by the progress of science.” And indeed the Duke looms in his period like a Churchill, an imposing, proudly archaic figure who fought with a frightening arsenal of rhetorical weapons and no apparent fear. His prose-just shy of florid, exquisitely structured and paced, embellished with metaphor, understatement, and backhanded malice-exudes the elegant malevolence of swordplay He had a particular knack for raising bloodlust while seeming to appeal only to the highest sensibilities. In the late 1880s, he played the role of antagonist in a controversy that tied the coral reef problem to the most contentious figures and ideas in science.

The coral reef controversy of the late 1880s emerged from an essay by a Duke ally, W. S. Lilly, who in November 1886 published “Materialism and Morality” in the prominent literary magazine the Fortnightly Review. Lilly, expressing earthily what the Duke had oft suggested, alleged that the positivism practiced by Thomas Huxley and others “reeks of the brothel, the latrine and the torture trough.” Huxley returned fire the next month. Lamenting that “the proprieties do not permit me to make [my response] so emphatic as I could desire,” he refuted Lilly’s positions. Two months later he opened a broader counterattack with a withering critique of the ideas of catastrophe and miracle titled “Scientific and Pseudo-scientific Realism.”

Enter the Duke, who responded to Huxley’s essay with one calling Darwinism a “muddy torrent of bad physics and worse meta physics” and complaining (in the sort of language guaranteed to fire the agnostic Huxley) of “the fumes of worship and of incense raised before the fetish of a Phrase [‘natural selection’].” Darwinian idolatry, the Duke said, was suppressing the scientific world in a “Reign of Terror,” and “it is high time indeed that some revolt should be raised.”

Huxley responded by trying to kick the Duke’s own high rhetoric from beneath him. “Can it be,” he asked, “that a guillotine is to be erected in the courtyard of Burlington House for the benefit of all anti-Darwinian Fellows of the Royal Society?”

The Duke had in mind no literal guillotine, of course. But after a few weeks, obviously having worked at it a bit, he revealed the instrument by which he hoped to decapitate Darwinist theory and idolatry. If evidence was everything, then he would offer a specific example of a sound, empirically based theory that Darwinists had unfairly repressed: John Murray’s coral reef theory.

2

For an attack, the Duke’s “Conspiracy of Silence” essay, as it came to be known, opened kindly. The Duke, writing now in another leading literary magazine, The Nineteenth Century, began with a glowing portrait of a Beagle-era Darwin who had “a mind singularly candid and unprejudiced-fixing upon nature a gaze keen, penetrating, and curious, but yet cautious, reflective and almost reverent.” He spends a good two pages painting a Darwin anyone could love-curious, humane, impartial, and graciously, lucidly eloquent. The Duke then takes another ten pages to describe, apparently admiringly, Darwin’s theory of coral reef formation. This glowing, even moving account, written as by an advocate, ends with the Duke’s acknowledging that the theory was not onlyingenious, showing deep thought and a thorough knowledge of almost all that was known on the subject, but beautiful:

There was an attractive grandeur in the conception of a great continent sinking slowly, slowly, into the vast bed of the Southern Ocean, having all its hills and pinnacles gradually covered by coral reefs as in succession they sank down to the proper depth, until at last only its pinnacles remained as the basis of atolls, and these remained, like buoys upon a wreck, only to mark where some mountain peak had been finally submerged. … It was a magnificent generalisation. … I have heard eminent men declare that, if he had done nothing else, [Darwin’s] solution of the great problem of the coral islands of the Pacific would have sufficed to place [him] on the unsubmergeable peaks of science, crowned with an immortal name.

He’s setting Darwin up, of course, raising him high so he can drop him far. The attack comes after fifteen pages.

And now comes the great lesson. After an interval of more than five-and-thirty years the voyage of the ‘Beagle’ has been followed by the voyage of the ‘Challenger,’ furnished with all the newest appliances of science, and manned by a scientific staff more than competent to turn them to the best account. And what is one of the many results which have been added to our knowledge of nature-to our estimate of the true character and history of the globe we live on? It is that Darwin’s theory is a dream. It is not only unsound, but it is in many respects directly the reverse of truth. With all his conscientiousness, with all his caution, with all his powers of observation, Darwin in this matter fell into errors as profound as the abysses of the Pacific.

The Duke’s beef is not, he says, with the late Darwin, who had tried to solve an enormous puzzle with the best information at hand (albeit with a bit too much imagination). His beef is with Darwin’s followers, who defend his views even when it means ignoring growing mounds of contrary evidence. Recent findings confuting Dar win’s coral reef theory, he says, show that

all the acclamations with which it was received were as the shouts of an ignorant mob… Can it be possible that Darwin was wrong? Must we indeed give up all that we have been accepting and teaching for more than a generation? Reluctantly, almost sulkily, and with a grudging silence as far as public discussion is concerned, the ugly possibility has been contemplated as too disagreeable to be much talked about. The evidence, old and new, has been weighed and weighed again, and the obviously inclining balance has been looked at askance many times. But despite all averted looks I apprehend that it has settled to its place forever, and Darwin’s theory of the coral islands must be relegated to the category of those many hypotheses which have indeed helped science for a time by promoting and provoking further investigation, but which in themselves have now finally “kicked the beam.”

And what had exposed this error? It was the reef theory of John Murray,

supported with such a weight of facts and such close texture of reasoning that no serious reply has ever been attempted… Here was a generalisation as magnificent as that of Darwin’s theory. It might not present a conception so imposing as that of a whole continent gradually subsiding… But… the new explanation was more like the analogies of nature-more closely correlated with the wealth of her resources, with those curious reciprocities of service which all her agencies render to each other, and which indicate so strongly the ultimate unity of her designs.

Thanks, however, to the “curious power which is sometimes exercised on behalf of certain accepted opinions, or of some reputed Prophet, in establishing a sort of Reign of Terror in their own behalf,” Murray’s new theory had produced only “slow and sulky acquiescence, rather than that joy which every true votary of science ought to feel in the discovery of a new truth and-not less-in the exposure of a long-accepted error.” The whole affair showed, said the Duke, that solid science was being held hostage by those who considered Darwin’s theories sacrosanct.

As a final slap at Huxley and his fellow travelers, the Duke dredged up the decade-old Bathybius debacle. This great mistake regarding the “mother slime” with the “fine new Greek name” had caught on, the Duke alleged, only because Darwin’s theory of evolution made the idea of Bathybius so attractive that it “ran like wildfire through the popular literature of science.” The farce ended only when the Challengercrew, with Murray playing a prominent role, discovered that the primordial ooze was just a labartifact. “This was bathos indeed,” punned the Duke, “a case in which a ridiculous error and a ridiculous credulity were the direct results of theoretical pre conceptions.”

It’s rare that an argument so lively and caustic-so much plain fun-carries such lyrical grace. The lyricism wasn’t just dressing. To begin with, it protected the Duke from the charge that he was blind to the beauty of elegant theory; the man gushed about ideas the way Louis Agassiz gushed about creatures. This style, and particularly the lovely account of Darwin’s theory also co-opted Darwin as an ally against his own supporters. By describing Darwin’singenious attempt so sympathetically and eloquently-all the while praising his renowned open-mindedness-the Duke sharpens his assault on the close-minded idolaters who would ignore new evidence.

In part, the Duke was making a wider argument that would be an accepted truism a century later: that science, being a social as well as an intellectual enterprise, is prone to errors of idolatry, pride, cowardice, and politics. A scientific orthodoxy (at least that of Darwin ism) could legitimize bad theories the way governments legitimized bad laws.

This infuriated the empiricists who championed Darwin. The Duke was calling them atheistic churchmen and closet idealists, pseudoempiricists who would adore a theory because it reflected an ideal order not in nature (much less God) but in the theory itself. In love with elegant thought, elated at being free of the restraints of religion, they worshipped not thoughts of God but those of man-and particularly of the man named Darwin.

3

Huxley responded with polite acidity and some deft stratagems of his own. He declared that given the difficulties of studying something so complicated as reef formation, he (who had spent three years among reefs) doubted there were ten people in the world fit to weigh the merits of Darwin’s and Murray’s theories. (Presumably the Duke, who’d never been to the tropics, wasn’t among them.) Then, turning to the Duke’s charges of idolatry and censorship, he hammered at the weak spots in the Duke’s argument.

“The Duke,” Huxley declared, “commits himself to a greater number of statements that are demonstrably incorrect… than I have ever seen gathered together in so small a space.” Huxley actually counted off the major errors (seven) and answered them in order. He noted, for instance, that when the Duke said that no one had attempted a serious response to Murray’s theory (incorrect statement number one), he overlooked Dana’s extended and highly specific rebuttal of 1885; that the “ignorant mob” that received the theory (error number four) apparently included Dana and other widely renowned men of science; and, most damningly that far from being ignored or suppressed (falsehood number six), Murray had published his theory in two major journals, Geikie had elaborated it in his 1883 Nature review article, and several recent geology textbooks discussed it. Huxley also rebutted in detail the Duke’s accusation (inaccuracy number seven) that Murray had been improperly discouraged from publishing his theory in the first place.

Huxley wasn’t the only one fuming. Many in the British scientific world had felt attacked, and some of them joined the fight. As the discussion moved from the monthly Nineteenth Century to the letters page of Nature(where “weekly publication,” as historian Susan Schlee put it, “allowed for a quicker and more satisfying exchange of insults”), the barrage leveled at the Duke provided one of the livelier strings of letters that Nature had yet run. John Judd, a prominent geologist and supporter of Darwin’s theory, cited the several textbooks and articles that had discussed Murray’s theory and quipped, “If [Murray’s treatment] be a ‘conspiracy of silence,’ where, alas! can the geological speculator seek for fame?” University of Lon don geology professor and immediate past president of the Geologi cal Society Thomas Bonney who would soon emerge as a major defender of Darwin’s theory despite his lack of coral reef experience, confessed he was “old-fashioned enough to resent being called a knave more than being called a fool” and said the Duke’s charges of repression suggested that he was either “strangely oblivious of, or, among the cares of a statesman, has failed to keep himself au courant with, the literature of geology.” (Several combatants voiced this pseu-dosympathetic lament that the Duke’s political duties must have left him behind; Bonney was the only one to season it with French.) When the Duke wrote a letter offering a second example of suppression, accusing the Darwinian establishment of stifling a paper Guppy had offered the Royal Society, Huxley quipped that “as fast as old misrepresentations are refuted, new ones are evolved out of the inexhaustible inaccuracy of his Grace’s imagination.”

This pithy fight about knavery quickly made the coral reef problem one of the most prominent and explicitly controversial in science. It also created, amid the sword work, the most thorough discussion yet of the arguments for and against the two theories.

Many who had not yet read Darwin’s and Murray’s theories now did, and virtually every scientist who had actually seen a reef chimed in. Murray was invited to present his theory (updated with additional data) to the Royal Society of London, and this updated account ran in Nature in early 1888, as did pretty much anything else Murray wanted to say on the subject.

The more substantive parts of the debate covered several key issues. One was Murray’s idea that lagoons formed not through subsidence but through solution of coral by seawater. Any reef-genesis theory had to explain how lagoons were created, and many of his peers considered Murray’s notion of lagoon formation the weakest part of his reef theory; quite a few, including some who favored Murray’s general theory, doubted that seawater dissolved corals fast enough to create lagoons. Others, echoing the objection Darwin had written to Alex, pointed out that if seawater did dissolve calcium-based material quickly enough to create deep lagoons, the same sol vent power should prevent the banks from piling high enough to provide coral foundations in the first place. Some who supported Murray’s larger theory about planktonic accumulation suggested other mechanisms that could account for lagoon formation. Captain William Wharton of the Royal Navy, for instance, an accomplished marine scientist who would soon become a rear admiral and hydrograph, reiterated the Eschscholtz-Chamisso observation that since corals grew most rapidly to seaward, a Murrayesque reef-one mounting on a sediment-formed bank-would naturally create a lagoon behind the faster-rising seaward edge or perimeter. Corals growing on island banks would thus form bowl-shaped atolls, and a shoreline bank could give rise to a barrier reef. If a rising reef took such a form, even modest destruction of the reef interior by solution, perhaps combined with the erosive power of current and tide, might produce even deep lagoons. Wharton’s lagoon-formation the sis was seconded by Oxford geologist Gilbert Bourne, whose long examination of the Chagos and other banks in the Indian Ocean led him to “conclusions nearly identical” to Wharton’s and quite opposite Darwin’s. “The true cause of the atoll and barrier lagoons,” wrote Bourne, “lies in the peculiarly favorable conditions for coral growth present on the steep external slopes of the reef.”

Wharton, who wrote carefully and tactfully, clearly not wanting a scrap, also stressed how little was known about the bathygraphy of most coral areas. Of the 173 larger islands in the Tuamotus, Ellice (now Tuvalu), Gilbert, Marshall, and Caroline Islands, for instance, only four had been even partially sounded. Data so sketchy hardly justified grand generalizations.

How to pull all this together? Guppy hoping to twist the various antisubsidence threads into a cord, noted that among those who accepted Murray’s account of reef foundations, the differences concerning the creation of lagoons were academic and likely solvable; they need not sink the theory. It might be, he suggested, that

in our present state of knowledge it will be wisest to combine in one view the several agencies enumerated by [Murray, Semper, Agassiz, and others] as producing the different forms of coral reefs. On the outer side of a reef we have the directing influence of the currents, the increased food-supply, the action of the breakers,. In the interior of a reef we have the repressive influence of sand and sediment, the boring of the numerous organisms that find a home on each coral block, the solvent agency of the carbonic acid in the sea-water, and the tidal scour. These are real agencies, and we only differ as to the relative importance we attach to each.

4

Alex must have given a shout of assent when he read Guppy’s plea. He too was becoming convinced that reefs were built by numerous forces that combined in different ways at different locations. He didn’t say so in Natures letters column, for that wasn’t his type of forum (though he was quick to tell Murray he was glad to see him speak up there). Yet the debate sparked by the Duke’s provocations did draw a response from Alex. The Duke flap happened to erupt just as Alex was finishing his long-gestated Blake report and his shorter monograph on the 1885 Hawaiian trip. His earlier papers on Florida and the Bermudas had largely avoided broad theoretical statements. Now he finally got explicit.

In Three Cruises of the “Blake,” Alex offered for the first time, briefly but plainly, an argument, similar in essence to the Duke’s coral reef comments but more measured, that the evidence against Darwin’s theory had reached critical mass. After making the case that the Florida and other nearby reefs formed atop sedimentary banks, he went on to say that

the evidence gathered by Murray, Semper, and myself, partly in districts which Darwin has already examined … tends to prove that we must look to many other causes than those of elevation and subsidence for a satisfactory explanation of coral-reef formation. … If… we have succeeded in showing that great submarine plateaux have gradually been built up in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean by the decay of animal life, we shall find no difficulty in accounting for the formation of great piles of sediment on the floors of the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Little else in Three Cruises hints at which theory should prevail. Alex reserved his longer say for his Hawaii monograph, a more logical place to address Darwin’s theory and one that may have felt safer, since Three Cruises was meant to be a popular book, while the Hawaii paper appeared in the Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. He opened with what amounted to a long review article-half of the forty-four-page paper, in fact. This is itself revealing, for the scientific-review article is usually an explicit attempt to shape (or reshape) the conclusions drawn from a body of work. Alexander clearly hoped to do just that: to show that the total body of reef research compelled replacement of Darwin’s theory with one less simple.

He began by rebutting some of the arguments leveled against Murray in the Nature exchange. He reserved a particularly curt dismissal for the mathematical arguments of T. Mellard Reade, a dry-footed mathematician who had called Murray’s overall theory “far-fetched” and who was especially critical of the lagoon-solution thesis. Such “investigators who know little of coral reefs from their own observations,” Alexander said pointedly, “have ignored or flatly denied facts which can hardly be dealt with in so summary a fashion.” Alex countered Reade’s objections with evidence from reef observers such as Jukes and himself as well as other lab experimenters.

Yet while Agassiz answered those objections to Murray’s lagoon-solution thesis, he also took pains to express his own reservations about his friend’s model, saying “it is pressing the theory too far … to consider [solution by carbonic acid] the principal cause of the formation of lagoons.” It was more likely he said, that lagoons were formed, as Guppy had suggested, through a combination of forces. He also agreed with another Guppy assertion, that the “new” accrual theory was itself built upon one of the earliest reef theories based on actual observation:

Chamisso* seventy years ago advanced the view that an atoll owes its form to the growth of corals at the margin [of a submarine bank] and to the repressive influence of the reef debris in the interior; but this view gave no satisfactory explanation of the foundation of such a coral reef [that is, how the submarine bank formed], and Darwin was driven to his theory of subsidence. The great defect in the way of Chamisso was, however, removed by Murray, who supplied the foundation of an atoll without employing subsidence, and investigation in the Florida Sea (Agassiz) and in the Western Pacific (Guppy) have con firmed his conclusions.

The confirming evidence, he emphasized, had come from a much longer list of researchers than just Guppy and himself. The harsh fact, he noted, was that only those who originally bought Darwin’s theory still supported it, while all subsequent investigators had found that the evidence argued against it. To Alex, this alone was reason to set aside Darwin’s theory.

With the exception of Dana, Jukes, and others who published their results on coral reefs soon after Darwin’s theory took the scientific world by storm, not a single recent original investigator of coral reefs has been able to accept [Darwin’s] explanation as applicable to the special district which he himself exam ined… The great mass of observations since the promulgation of Darwin’s theory is on the side of the more recent explanation of the formation of coral reefs, while the older theory rests upon an hypothesis of which it is under most circum stances extremely difficult to obtain any proof whatsoever.

He then took a dozen pages to detail the evidence against Darwin and for an accrual theory as it had emerged in journeys that not only covered most of the world’s tropical coral reef areas but that together outweighed what Darwin and Dana had seen. There had been Louis Agassiz, J. J. Rein, and himself in the Atlantic and Caribbean, and Forbes, Semper, Guppy, and Bourne “in the very regions explored by Darwin” (the Pacific). In each case he explained how the researcher’s key findings refuted both Darwin’s generalizations and his theory’s applicability in the explored region. Finally, he described how his own Hawaiian findings, particularly the borings that showed only thin layers of coral, contradicted Darwin’s generalities and Dana’s assertion that Hawaii was formed through subsidence.

Alex’s long catalog of evidence expressed well his basic con tention and his belief in how science worked. As observation piled atop observation to raise the pile of evidence higher, the conclusions became obvious. This was science working properly: not through intuitive leaps and study of maps but through eyes-on observation and the tireless accumulation of reliable information.

That was his evidentiary argument. He also articulated an explicitly methodological argument: Darwin’s theory, he insisted, was both circular and speculative in its reasoning, and as such had to be rejected as a matter of principle, especially in the face of a more empirically based and better-documented accrual theory. Science was about evidence, not beautiful ideas. We cannot buy a theory that is its own proof. Yet that is what Darwin and Dana asked. “Darwin and Dana have assumed a possibility as a fact, and, the theory once given, have attempted to prove the subsidence instead of bringing the subsidence of coral reefs as a proof of the theory.” Committed to using an unprovable subsidence to explain reefs, they had resorted to using the reefs themselves to prove the premise: What makes reefs possible? Subsiding land. How do we know the land subsides? Because there are reefs. No certain knowledge-no known fact, no proven process, no unambiguous observable evidence-held this circle together. It rested on strength of reason-a sort of faith in the logic.

Such speculations occurred when you jumped to conclusions too soon. This was clearly true of Darwin, Alex argued, who, “it should be remembered, examined only the Great Chagos Bank, and based his speculations on the observations he made on this single group.” But it was also true of Dana, despite all his field experience. In his Hawaii report, having worked some of Dana’s tracks, Alex took a first shot at rebutting him directly, and his attempt illustrates what a vexing problem Dana presented to him. Alex tried to deal with Dana both by emphasizing Dana’s differences with Darwin-using him to damn Darwin, in other words-and by dismissing Dana’s agreements with Darwin as observational mistakes made under the sway of Darwin’s theory. He discarded Dana’s speculations about the timing and extent of subsidence as “immaterial” next to the question of whether reefs require subsidence at all. He acknowledged that reefs doubtless did sometimes form atop subsiding areas but argued that if they formed on stable or rising areas as well, then the subsidence the ory was not the sweeping, complete explanation it was said to be. Likewise the theory was wrong, or essentially useless as science, if subsidence could not be proven.

And this, he said, was precisely the case. Certainly Darwin hadn’t proven subsidence, for he had seen only a few reefs. Neither had the many who based their conclusions on charts. And neither had Dana, who despite his vast field experience had few soundings to document his assertions and so had to rely instead, even in the face of consider able evidence of elevation, on topographical features such as his famous drowned-valley fjords to “prove” subsidence. It was, he con cluded, “a most unsafe method of reasoning.”

As he was writing these words, Alex was again beginning to feel that his side was winning. The row over the “conspiracy of silence” had made quite a stink, but the ensuing debate revealed where the weight of evidence lay. In April, as he was composing his Hawaii paper, he wrote Simper, “After all that has of late been written against the theory of subsidence I do not believe we shall hear much again of Dar win’s theory.”

This confidence faded, however, as the Duke of Argyll controversy continued into 1889 without seeming to convince any promi- nent subsidence advocates or fence sitters. Then came a double blow that knocked Alex’s hopes into sand. Late 1889 and early 1890 brought new editions of Darwin’s and Dana’s coral reef books, the reception of which showed that while the balance may have tilted away from Darwin, his theory still held substantial ground. Both books staunchly maintained, as Dana stated at the end of a new section in his book dismissing Agassiz’s and other objections, that “Dar win’s theory … remains as the theory that accounts for the origin of atolls and barrier islands.” The landlubber Thomas Bonney, mean while, concluded likewise in a literature review appended to the new Darwin edition, saying it was “premature to regard the [Darwin] the ory … as conclusively disproved.”

These prominent entrenchments from either side of the Atlantic, representing the two men still seen (though in Alex’s opinion with little reason) as the world’s leading coral reef authorities, seemed to epitomize the staying power of the Darwin theory. It was hard to say which was more exasperating. Here you had Bonney-a man whom Darwin’s son, Francis, had chosen as editor of the new edition despite a complete lack of reef experience, and who only three years before, in his first letter to Nature on the Duke of Argyll flap, had said that he felt qualified only to comment on the “literary” aspects of the coral reef controversy-presuming to pass judgment on phenomena and structures he had never seen. Bonney was backed by another British geologist with no field experience in coral reefs, John Judd (the series editor for the new geological editions Francis Dar win brought out in 1889), who in a preface opined that “while … Darwin was betrayed into some grave errors, yet the main foundations of his argument have not been seriously impaired by the new facts observed in the deep-sea researches, or by the severe criticism to which his theory has been subjected during the last ten years.”

Dana, meanwhile (seventy-seven by then), seemed willing to go to any length to deny the significance of the evidence against the theory he’d fallen in love with a half century before. In response to Guppy’s damning observation that in the Solomons “the coral reef rock forms a comparatively thin layer” over several hundred feet of elevated sedimentary limestone-extremely strong evidence that subsidence played no role in forming this prominent atoll-Dana said the Solomons “only prove that in coral-reef seas corals will grow over any basis of rock that may offer where the water is right in depth and other circumstances favor. They are not evidence against the subsidence theory but simply local examples under the general principle just stated.” This had to have sparked a howl from Alex, for to him it was the very fact that “corals will grow over any basis of rock that … depth and other circumstances favor” that both negated and obviated the subsidence theory. Yet here was Dana insisting that this particular instance (a major archipelago) was not merely an exception to the rule of subsidence but that this exception somehow proved the rule. Apparently the rule of subsidence was one that no number of exceptions could disprove.

The whole thing was getting to be too much. It especially irked Alex that scientists would accept on faith such a huge, nearly Pacific-wide movement to explain something that occurred in so many locations and circumstances. To Alex, pointing to a huge, unproveable subsidence as a cause improved only slightly on pointing to God’s hand.

“It is remarkable,” he wrote in his Hawaii paper, “that Darwin, who is so strongly opposed to all cataclysmic explanations, should in the case of the coral reefs cling to a theory which is based upon the disappearance of a Pacific continent, and be apparently so unwilling to recognize the agency of more natural and far simpler causes.” Dar win’s coral theory was indeed beautiful. Unfortunately, it defied both the mass of evidence and the principles of empirical practice. Alex could fathom its stubborn persistence only by recognizing in it what Lyell had once seen in Louis’s plan of creation-that for many people, the idea was so lovely that they could not help but want to believe it.

The stubbornness of Darwin’s theory seemed to prove the dangers of the deductive method that Bacon had tried to counter. Coral reef theory had become slave to a tyranny of premise, and those such as Huxley and Dana who championed subsidence were indulging in something close to idealist thinking. “I cannot understand why Dana should … not see the force of the argument against subsidence,” Alex wrote Semper, “and it is most confounding that Huxley [and Darwin] … should both be ready to call upon a ‘deus ex machina’ to account for what can so easily be explained by more simple causes.”

Perhaps most disturbing was the idolatry that the Duke had referred to-a personalization of theory that carried dangers to which Alex was particularly sensitive. Alex had seen Louis’s defen-siveness about species creation infect all his work; now he saw the defensiveness that Darwin’s supporters had developed during the Origin controversy spread over anything the man said.

Alexander’s sensitivity to such zeal was only heightened by his discovery, reading Darwin’s Life and Letters in late 1887, that Darwin had been quietly but ferociously ambitious and constantly pushed his agenda behind the scenes. In a letter to Murray that December, a letter that he begins by expressing his dismay at Huxley’s defense of Darwin’s coral theory, Alex writes, “I was surprised … to see the elements of [Darwin] pushing his cause … brought out so persistently [in Life and Letters]. The one thing always claimed by Darwin’s friends had been his utter unselfishness and absolute impartiality in his own cause. Certainly his correspondence with Hooker, Huxley and Gray shows no such thing.” Alex was doubtless referring to the correspondence of the late 1850s and 1860s, when, along with cultivating his British allies and bulldogs, Darwin cheered Gray on in the American debates that so diminished Louis. It could not have helped to read of his father being ridiculed: “It is delightful to hear all that [Gray] says on Agassiz,” Darwin wrote Hooker in 1854, in a letter reproduced in Life and Letters.“How very singular it is that so eminently clever a man, with such immense knowledge on many branches of Natural History, should write as he does.” Alex, writing Murray in the midst of the Duke of Argyll flap, tries to forgive Darwin even as he points out these faults, saying it’s a delightful book regardless. Yet there’s no mistaking his sense of betrayal as he recognizes the self-serving behavior of the man who dethroned his father.

The tangle he had entered was wrapping its vines about him. To pursue good science, it seemed, was to take on his father’s nemeses. With the coral reef controversy of the late 1800s-the polarization of opinion, the explicit layering of a methodological debate atop the consideration of evidence, the reentry of old Origin-era antagonists like Huxley and Dana-Alex’s scientific and personal fates had merged. They had done so long before, of course. But this time he seemed to recognize it in ways he had not earlier.

And so amid the echo of Darwin and Dana’s new editions, with the longest scientific discussion of reef theory to date leaving things unresolved, he decided to return to sea. He would sail in much the same spirit in which he had sailed to Florida and Hawaii, hoping to gather enough facts to outweigh the evidence of Darwin and Dana. But this time he would go to the very isles from which Darwin’s the ory had risen; he would go where Darwin and Dana had gone, see what they had seen, and cut the ground from beneath them.

There was another difference as well. When he had gone to Florida and Hawaii, the reef debate had been low-key, genial, and, as far as he could see, reasonably untainted by personalities and ideology. He had discussed the central points of contention cordially and productively with the man who had spawned the theory, a man who literally asked to be corrected-“knocked on the head,” as he put it-if he was wrong. But after the blood spilled over the conspiracy of silence, the revelations of Darwin’s own ambitiousness and back stage maneuverings, the insults delivered Murray by Huxley and himself by Dana, Alexander now understood quite well that he was entering an arena in which the lights were bright and the audience excitable, and in which everything, particularly the stakes, tended to be magnified. Though Darwin was dead, it was clear Alex would have to do more than knock him on the head with a few new facts. He had to bury him.

He lacked the youth that had blessed Darwin and Dana when they sailed. But he had time enough, immense expertise, and a great deal of money.

*Alexander here unknowingly repeats the historical misattribution of Eschscholtz’s idea to Chemise.