Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral - David Dobbs (2005)

Part II

Chapter 12. Accrual

I

AT FIRST IT appeared it might be easy, if you can call easy a decade that included several expensive and grueling sea journeys and some scientific tug-of-war. But within a few years of Alexander’s pledge to Murray to “investigate coral reefs,” he, Murray and others accumulated enough evidence to confidently believe they were displacing Darwin’s theory with another one more multifaceted and accurate.

The first step was the paper that Murray read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh and then published in its proceedings as well as in Nature(then a more popular and less technical science journal than it is today) in 1880. “The Structure and Origin of Coral Reefs and Islands” offered a well-documented argument that Darwin’s “simple and beautiful theory,” though “universally accepted,” was wrong. After describing Darwin’s subsidence theory in fair-minded and admirably concise language, Murray observed that in the time since its rapid acceptance, most investigators had “experienced great difficulty in applying Darwin’s theory” to the coral isles and atolls they actually encountered. He then stated that his goal was “to show … there are other agencies at work [besides subsidence] … by which submarine elevations can be built up from very great depths so as to form a foundation for coral reefs [and] that all the chief features of coral reefs and islands can be accounted for without calling in the aid of great and general subsidences.” In short, Dar win’s theory was not accurate or even necessary, for a better one was at hand.

He then presented a quantified elaboration of what he had told Alex in Edinburgh: that in every ocean throughout the world, the Challenger and other ‘post-Beagle cruises had found numerous mountain ranges and other banks that rose to within one thousand fathoms of the surface; that in the tropics, planktonic skeletons fell steadily and heavily enough on these mid-depth platforms to raise them to coral-friendly depths; and that the formation of these accrued slopes, along with the advance of the thickening talus slope on the reef’s outer edge and the solvent action of seawater in the lagoon behind, could explain every feature of every type of reef, fringing, barrier, and atoll. The “submerged banks” on which reefs form, he said, “are continually in the process of formation in the tropical regions …, and it is in a high degree probable that the majority of atolls are seated on banks formed in this manner.”

With his own alternative theory presented, Murray then described one archipelago after another that researchers had found to contradict Darwin’s theory. This catalog included Tahiti, where Darwin had his mountaintop epiphany; the Maldives, a vast Indian Ocean atoll that Darwin did not visit but that he considered a particularly strong argument for subsidence; and the Fijis, which Dana had claimed was an almost ideal illustration of Darwin’s principles. Murray pointed out that the heart of Darwin’s theory, the idea that most reefs form on sinking volcanoes, conflicted with the long, well-known association of volcanoes with elevation. Murray didn’t know it, but his doubts about this contradiction had been shared by Lyell-who, having died in 1875, was now spared having to decide whether to respond to Murray’s expression of them. “There has always seemed to me a difficulty,” Lyell once confessed to his journal in 1856, “in reconciling two facts in Darwin’s theory of volcanic and Coral areas-namely that Volcanoes are the upheaving power and yet, that nearly all the islands in the middle of great oceans are volcanic.”

Murray was more direct. “Throughout the volcanic islands of the great ocean basins,” he wrote, “the evidence of recent elevations are everywhere conspicuous,” while evidence of subsidence was rare. It was true, he admitted, that signs of subsidence tended to be hid den or ambiguous. But that didn’t mean they could be assumed, and they in fact needn’t be looked for. Given tectonic elevation and planktonic sedimentation-causes that are “proximate, relatively well known and continuous”-“it is not necessary to call in subsidence to explain any of the characteristic features of barrier reefs or atolls.”

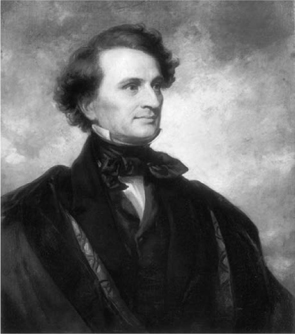

Yale geologist James Dwight Dana, whose voluminous observations on Pacific reefs supplied the main evidentiary support for Darwin’s reef theory

It was a good argument, delivered cleanly and with an occasional touché. It did not immediately win over Darwin’s advocates, but this didn’t bother Murray or Agassiz. For it gave the many public doubters of Darwin’s theory an alternative to gather around, and these scientists, who included several of the world’s most experienced coral reef observers, immediately began developing and elaborating Murray’s idea. Secret doubters and undecideds likewise gained an alternative, and many scientists who had not already made up their minds, as well as some who had previously accepted Darwin’s theory, now decided to remain neutral and wait for more research. Murray and Agassiz saw this as a significant victory. Almost every serious coral reef researcher since Dana had found reason to doubt the subsidence theory. More data would only strengthen Murray’s hand.

2

That Darwin himself remained unconverted surprised no one. Yet Murray’s theory got his attention and, if you wanted to read him that way, opened some doubt in his mind. Alex discovered this not long after Murray’s paper came out, when he sounded out Darwin with a letter from off the tip of Florida. He wrote from the U.S. steamer Blake, tanned, tired, and with several volumes of new reef data freshly recorded from the last of three research cruises off Florida and the Caribbean that he took from 1877 to 1881. While these were general, comprehensive oceanographic expeditions, with extensive bathymetric soundings and zoological collecting, they mark the beginning of Alexander’s serious coral reef work. Seven years later he would publish the results of those cruises in the two-volume Three Cruises of the “Blake” a thick and sometimes dense report that nonetheless contained enough evocative passages and illustrations to sell well. (Apparently there was still demand for natural history works by an Agassiz, even sans metaphysics.) In Three Cruises he would argue that the foundation underlying the Florida reefs, along with the entire peninsula and its vast surrounding shoals, was created by deposition of not just planktonic debris but the remains of huge numbers of animals brought there by the Gulf Stream. Atop these banks, which had been formed long ago and had scarcely moved up or down since, the coral merely formed a thin veneer. “This explanation,” as he would put it in Three Cruises,“tested as it has been by penetrating the thickness of the beds underlying the coral reefs, seems a more natural one … than that of… subsidence.”

By the time he wrote Three Cruises, Alex had enough confidence in Murray’s theory to cite Florida as a first proof that deposition could work globally. “If… we have succeeded in showing that great submarine plateaux have gradually been built up in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean by the decay of animal life,” he wrote, then “we shall find no difficulty in accounting for the formation of great piles of sediment on the floors of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, pro vided these banks lie in the track of a great oceanic current.” For now, however, writing Darwin from the Blake, Alex stuck to local specifics:

TORTUGAS, l6 APRIL l88l

It is very natural you should be in my mind, as I am in the midst of corals… The Tortugas being the very last of the Florida reefs [to be researched] I find much that has not been noticed before and helps to explain, somewhat differently from what was done by Father, the formation of the reefs… Every thing … tends to show that the immense plateau which forms the base upon which the Peninsula of Florida is formed, was built up by the débris of animal remains,-Mollusks, Corals, Echinoderms, etc. (after it had originally reached a certain depth in the ocean), until it reached the proper height for corals to flourish.

This was hardly news to Darwin. He had acknowledged in the 1872 edition of The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs that the banks around Florida and in the Caribbean “clearly show that their origin must be chiefly attributed to the accumulation of sediment.” He saw the region as an exception to his theory.

Alex’s letter, then, might have drawn a blunt rejoinder pointing out Darwin’s prior caveat on Florida and noting that Alex’s Florida findings didn’t really speak to the larger subsidence argument. It might have drawn such a rejoinder, that is, were Darwin a different sort of polemic. Instead, Darwin responded with a rebuttal that was simultaneously concession, counterargument, and invitation. It’s an extraordinary letter, classic Darwin in its graciousness, its mixture of spirited assertion and humble consideration, and its noncommittal commitment to open-mindedness. Even while defending his view and questioning Murray’s, he allows doubt about his own theory- and flatters Alex that he, perhaps more than anyone, has the resources to settle the issue.

5 MAY l88l, DOWN

It was very good of you to write to me from Tortugas, as I always feel much interested in what you are about, and in reading your many discoveries. It is a surprising fact that the peninsula of Florida should have remained at the same level for the immense period requisite for the accumulation of so vast a pile of debris.

You will have seen Mr. Murray’s views on the formation of atolls and barrier reefs. Before publishing my book, I thought long over the same view, but only as far as ordinary marine organisms are concerned, for at that time little was known of the multitude of minute oceanic organisms.

With his “only as far as …” he admits that his theory had not considered the rain of planktonic debris Murray had found. Yet he goes on to disallow Murray’s idea anyway, at least for the time. “I rejected [Murray’s] view,” he wrote, “as from the few dredgings made in the Beagle in the S. Temperate regions, I concluded that shells, the smaller corals, etc., etc., decayed and were dissolved when not protected by the deposition of sediment; and sediment could not accumulate in the ocean open.”

He then casts doubt on Murray’s central mechanism-but immediately pulls his punch:

I have expressly said that a bank at the proper depth would give rise to an atoll, which could not be distinguished from one formed during subsidence. I can, however, hardly believe in the former presence of as many banks (there having been no subsidence) as there are atolls in the great oceans, within a reasonable depth, on which minute oceanic organisms could have accumulated to the thickness of many hundred feet… Lastly, I cannot understand Mr. Murray, who admits that small calcareous organisms [such as planktonic debris that supposedly build up the banks] are dissolved by the carbonic acid in [sea] water at great depths, and that coral reefs, etc., etc., are likewise dissolved near the surface, but that this does not occur at intermentdiate depths, where he believes that the minute oceanic organ isms accumulate until the bank reaches within the reef-building depth. But I suppose I must have misunderstood him.

We see what Alex is up against: a mind agile, determined, and gracious. He could hardly be more dangerous. Darwin is like the wizened martial arts teacher, warm hearted but deadly, who humbly compliments your efforts even as he deflects your every blow and occasionally delivers, from nowhere, a smack upside the head. Dar win’s graciousness is genuine. But it’s also a serious weapon meant to disarm. When he says in a kindly tone that he finds a fact surprising or an idea’s meaning elusive, it’s never clear whether we should consider the stupid thing to be him or the fact or idea-until we realize that since it’s Charles Darwin speaking, chances favor the latter. He shows too the smoothness of the passive-aggressive dinner host who raises a contentious subject just long enough to score a point, then forestalls response by sweeping the subject away as too odious. He even manages to wield the same phrase as sword and shield in a single paragraph: “I cannot understand Mr. Murray [in his insistence that shells dissolve in shallow and deep water but not at medium depths],” he says to open the attack that he ends with the disarming “But I suppose I must have misunderstood him.” It all seems calculated (or, more to the point, spun with unconscious ease) to destroy Murray’s argument while launching a preemptive strike of politesse to prevent counterattack.

But then, just when he has genially painted Murray’s theory as an unworkable stretch and left Alex almost no equally gracious way to differ strongly, Darwin, in another combination of directness and obliquity, suggests that he might have got everything wrong after all and so perhaps an adjudicator is needed-and that Alex, with his expertise, knowledge, and money, is best qualified to serve:

Pray forgive me for troubling you at such a length, but it has occurred to me that you might be disposed to give, after your wide experience, your judgment. If I am wrong, the sooner I am knocked on the head and annihilated so much the better… I wish that some doubly rich millionaire would take it into his head to have borings made in some of the Pacific and Indian atolls, and bring home cores for slicing from a depth of 500 or 600 feet.

This makes a strange call to action. It recalls the dance with which Darwin led Gray along in their extended and oblique correspondence about plant distribution before confessing his evolution theory. Was he doing the same here with Alex, only inviting him to prove him wrong? One can’t quite call his request for Alex’s clarifying opinion a challenge; the tone is too gracious. Yet his astonishing mix of antagonistic counterargument, seemingly modest half-admissions of thin evidence and poor thinking, and flattery amounts to a dare. The wish for a “doubly rich millionaire” is a particularly deft touch; Darwin knew well that Alex was trebly rich. The final, irresistible goad is the suggestion that a few hard facts might settle the whole issue. The deductive theorist is cooking a meal the aroma of which the inductivist investigator can scarcely resist.

Darwin wrote Alex this letter on May 5,1881. When Alex found it on returning to Cambridge from Florida two weeks later, he wrote back immediately. His response matches Darwin step for step in a dance of half-concession, correction, and counterproposal. He be gins by confessing that he thinks Murray might be overplaying the planktonic-debris factor; to him it seems more likely that planktonic debris are joined by the skeletons of mollusks, starfish, echinoderms, crustacea, and other bottom dwellers to build more solid, current-resistant banks than Murray proposed. As to the question of shells and planktonic skeletons dissolving at different rates at different depths, Alex, mirroring Darwin nicely in his disarming false modesty, says he wouldn’t really know about that, but in his experience (which he needn’t trumpet, since Darwin has just acknowledged it as wider than his own) calcareous skeletons actually stay “fairly well preserved after death” once they’ve reached bottom. He finishes this polite opining by saying that he still sides with Murray, with some caveats, and agreeing amiably that more facts are indeed the key to settling the matter: “Your objection that there is not a great probability of finding in the Pacific as many banks as there are atolls is … one which seems to me can only be met by showing in subsequent surveys that these atolls are themselves only slightly raised patches upon large banks… This is a problem … which I have had in view for a long time and hope to solve one of these days.

Eleven months later, on April 19,1882, before the two could continue this correspondence, Darwin died. He was seventy-three. His death, and the convivial tone of his brief exchange with Alexander on coral reefs, leaves us to wonder whether these two men, who seemed to share an extra mutual regard for having found in each other an unexpected warmth and open-mindedness during Darwin’s feud with Louis two decades earlier, might have advanced the coral reef debate along more constructive lines than it ended up following.

Such speculation is moot, of course. One might just as readily have predicted that Darwin’s exit would allow a more objective, less personality-laden consideration of coral reef genesis. But that hardly proved the case either.

3

For three years, health problems, other travels, the demands of running the museum, and the composition of Three Cruises of the “Blake”(five hundred pages thick with illustrations) prevented Alex from reaching the Pacific. In December 1884, however, he sailed to Hawaii (then still called the Sandwich Islands) and spent two months looking for signs of elevation and subsidence. He saw “[everything] there was to be seen in the way of coral reefs” on Oahu and much on Maui and Hawaii as well, and he exhaustively reviewed previous reports. Dana and others who had been there before him had done most of the sounding work, so he was free to move quickly between places to examine the physical structure of the corals. Without a boat himself this time, he usually hired fishermen to take him over the reefs in their outrigger canoes so he could peer down on the coral. At other times he borrowed a boat and rowed himself out over the reefs. He talked to well drillers and copied their bore records to see what strata they punched through when looking for water. Everything he found confirmed his feeling that Hawaii, his first Pacific reef area, fit Murray’s model of an advancing reef atop an accrued bank better than it fit Darwin’s subsidence theory.

When he got back he wrote Dana, whom he had also written before the trip. In both letters Alex steers clear of any sharp differences.

You will be interested to hear that while at Sandwich Islands I followed in your tracks and explored the area pretty thoroughly [and discovered] some interesting points. … I must now look up carefully all you have done … and shall then take the first opportunity of publishing a short paper on the reefs of the Sandwich Islands. What a delightful place these islands are. It seems a … paradise, especially as called up on a raw specimen of a New England spring day.

It’s the tone of someone seeking the camaraderie of two old friends who disagree about something they love. Alex would respond much differently when he read Dana’s next reef paper a few months later.

Meanwhile he had reason to take heart in the increasing number of researchers who said that their field observations in the Pacific didn’t agree with Darwin. Such objections had actually begun decades earlier. Louis Agassiz, as mentioned before, had found in 1851 that the Florida reefs didn’t appear to be the result of subsidence. The German geologist J. J. Rein had concluded the same about the Bermudas in the 1860s, and Alexander himself had corroborated these views and expanded them to the Bahamas in his Blake cruises. Carl Semper’s 1860s examination of the Palau Islands (now called the Pelews, part of the Carolines) had found them incompatible with the subsidence theory. And Henry Forbes, visiting the Indian Ocean’s Cocos atoll in 1879, saw neither signs of subsidence nor any necessity to call on it to explain this atoll that Darwin had found so confirming.

These pre-Murray refutations, having no theory of their own to reinforce, had received little attention. Once Murray published his theory, however, refutations got more play, though most appeared in the proceedings of the Murray-friendly Royal Society of Edinburgh rather than in Nature. H. B. Guppy, cruising the Solomon Islands in HMS Lark in 1882-1884, concluded that subsidence played no role in creating this large archipelago just east of Papau New Guinea; rather, the Solomons’ barrier isles and atolls formed roughly as Mur- ray suggested, starting atop banks or in the shallows around volcanic islands and then extending outward on talus while erosion and solution formed lagoons behind. Gilbert Bourne, an Oxford professor and later director-general of the General Survey of Great Britain, closely investigated the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean and decided that though “Darwin [working from charts] considered that the Great Chagos bank afforded particularly good evidence of the truth of the subsidence theory… [a] more intimate knowledge of the Great Chagos Bank … shows this view to be untenable.”

Alex, meanwhile, was slow to publish his own results about either the Blake or the Hawaii trip. He had the usual distractions of mine, museum, and other work, but it also seems he was hesitant to enter a fray in which he might be quickly identified as a leader. It was a strange time. The mounting evidence and number of opponents against the subsidence theory made it a good moment to lead a charge. But having seen his father fare poorly from them, Alex viewed tussles between men rather than ideas as a destructive distraction rather than as how science should be done. He felt strongly that if an idea was solid enough, it would win out. And as evidence against Darwin’s theory piled higher in the 1880s, he had reason to believe that its weight would tilt the scales without him. The cause already had two worthy champions: Murray, who held unequaled prominence as an oceanographer, and Archibald Geikie, the director-general of the General Survey of Great Britain. In 1883 Geikie had greatly bolstered Murray’s theory by publishing a long review article in Nature that summarized the breadth of evidence contrary to Dar win’s theory.

Alex thus left most of the publishing to others, communicating his own findings either slowly or in letters. He wrote Dana and Mur ray with similar frequency and congeniality. He sought to keep his end of it a collegial tug of ideas and (more to the point, since he always valued evidence above abstractions) evidence. He seemed to assume that both men would recognize the implications of the mounting evidence against Darwin’s theory.

He got a dose of reality in the fall of 1885, when he read a new thirty-eight-page paper from Dana, “Origin of Coral Reefs and Islands.” Alex had just written Dana another in that year’s series of friendly-rivalry letters, ending it with a comradely confession: “It has been one of my dreams,” Alex told Dana, “to make an expedition with modern methods to the great coral areas of the Pacific and with Calumet’s financial success I hope I now may secure a vessel to go solve what I look upon as one of the most interesting problems in geology, the array of Pacific Islands and the whole subject of coral reefs.”

In his paper, however, Dana made it clear that he considered the problem already solved. In a tone that sometimes drifted toward sarcasm, he vigorously rebutted the new attacks on Darwin’s theory and specifically refuted Murray’s argument. He also claimed the empirical high ground, asserting that with the importance that Murray and his supporters gave to field experience (and Darwin’s lack thereof), and “knowing that we are all for the truth and right theory, [I have] reason to believe that those who have been led to object to Darwin’s conclusions will be pleased to have their objections reviewed by one who has a personal knowledge of many of the facts.” Dana was flashing the trump card he still held as the single most widely experienced reef observer.

Alex was both miffed and strangely heartened. He found it encouraging that Dana felt a need to refute Murray’s theory. And Dana’s rebuttal could be read in places as a retreat. Dana here with drew, for instance, the notion of a vast, continent-size area sinking, allowing that the area of subsidence might not prove as extensive as suspected before. But he also said that even if he and Darwin were wrong about an entire continent’s sinking, that exaggeration did not detract from the value of the central thesis: Subsidence could just as well occur more locally or within certain regions or arcs.

Yet if he showed some signs of moderation, Dana clearly didn’t intend to surrender: He spent twenty-two of his thirty-eight pages countering every one of the objections cited by Geikie in his long, damaging review of two years before. He also threw new, painful darts at Murray’s work, reinterpreting Challenger soundings to sup port Darwin’s theory instead of Murray’s. And he finished by declaring Murray’s and others’ theories “incompetent” and stating that “the hypotheses of objectors to Darwin’s theory are alike weak… Dar win’s theory therefore remains as the theory that accounts for the origin of coral reefs and islands.”

Alex was taken aback. The margins of his copy of Dana’s paper are filled with annoyed rejoinders like “not at all,” “why so?,” “why not?,” “facts not so,” “[Darwin] never saw them,” “oh no such thing,” “badchart,” “what has that to do with coral?,” and, regarding Darwin’s reliance on charts to interpret the structure of entire archipelagoes, the crucial “danger of leaps.” The paper cooled his attitude toward Dana. It instantly put an end to the letters Alex had been writing him about the beauty of the Pacific islands and the interesting problems that remained.

Yet still he hesitated to enter the fray. He was at that point writing up his Hawaii report and struggling with even more revisions to Three Cruises. He also continued to tend the museum and mine and had started, at his big summer place in Newport, a small summer research institute for advanced students from the Museum of Com parative Zoology and elsewhere.

The Newport house, in fact, had become a great pleasure to him, and by this time it held a draw that almost outweighed his ambivalence about home, his aversion to New England winters, and, at times, his desire to pursue the coral reef question. The house-a mansion, really, with more than two dozen rooms-was built on a point of land that gave great views as well as easy access to both Nar-ragansett Bay and the open Atlantic. Alex had started spending summers there in 1875, working in a special room outfitted as a lab, and in 1877 he had constructed a research laboratory in an entirely separate building. The place even had microscope tables that rested, each via its own brick pier, directly on the granite ledge beneath the lab so that footsteps wouldn’t vibrate the instruments. Seawater, pumped into live tanks by a windmill on the point, was oxygenated with com pressed air to allow the keeping of live specimens. He soon added another wing for his own private offices and lab. Every summer a dozen or so students came (some of them yearly for almost two decades) to pursue largely independent study there-a sort of pre cursor of the summer research programs that would later be established at Woods Hole.

Here, during summers in the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s, Alex happily studied yet more echinoderm embryology as well as such matters as how flounders change their colors to match whatever surface lies beneath them. It was a comfortable return to small questions. He stayed out of the students’ hair for the most part, concentrating on the satisfaction of doing his own work undistracted by anything other than afternoon horseback rides with his sons. By the 1880s the comfort of this routine had eased the intense restlessness he’d felt in the mid-i870s. His health also weighed heavily in his consideration of how avidly to pursue the reef question. He was in his forties now, and a combination of leg problems and what were diagnosed as circulatory ailments combined with his susceptibility to seasickness to forbid sea journeys much of the time. (A particularly harsh bout of seasickness can quickly convince almost anyone that death is near; because Agassiz’s doctors had told him he risked precisely that, his sufferings were that much more distressing. He was as seasick on his trip to Hawaii as he’d ever been.) At other times-twice during the 1880s-his health was too fragile in winter to do more than travel overland to Florida (where he stayed ashore) or the American West. Most other winters during this period he traveled mainly on land, boarding boats only to cross the sea rather than study it. He journeyed to Egypt and North Africa, Mexico, India, Europe, and Japan. These visits of escape began to seem not merely distractions, as they had been in the late 1870s, but pleasurable goals. Fond of roughing it but with the money to rest or travel in luxury when he desired, he enjoyed these trips tremendously. He loved, for instance, trying to figure out the geology of the Sahara, and he made a rigorous hobby of hunting for artifacts and photographing ancient architecture.**

Next to this, the risks and discomforts of further journeys on the Pacific were daunting. As the 1880s wore on and he passed fifty, it increasingly seemed sensible not only to let others wield the pen against Darwin’s theory but to let younger men do the field research as well. Some already were. In the 1880s alone, researchers such as Guppy and Bourne were rapidly adding new archipelagoes to the list of those that defied Darwin’s theory. Alex had reason to believe that such fieldwork would eventually win the day.

By the nature of it, of course, it was hard to know how decisively the coral reef issue was moving his way. A multifaceted, localityspecific, conditional explanation like his would not be suddenly hailed far and wide but would gain credibility only gradually. It would not setin with the sudden power of an epiphany, for unlike an epiphany it was not simplistic. For Alex, this was almost the whole point. Later he would come to favor a particular model of reef building. But for now his explanation was so conditional that it was almost an antitheory: He was pushing the idea that no single theory could cover all or even most coral reefs, that instead the origins of each reef system must be considered separately. Such an explanation could win out only in suitably subtle fashion, one reef system at a time.

As he worked up his Hawaii notes in the mid-i88os, precisely this seemed to be happening. The reports of Bourne, Guppy, Rein, and others were pebbles that would raise the theory high enough to obscure Darwin’s simple, shimmering idea. Let Dana be stubborn. He was only one man. Most scientists without entrenched interests were feeling that Darwin had overreached. Alex had reason to believe that as more reef data accrued, a more multifaceted model would win. It would take some time, but it was happening. And that was all right. That was how science worked.

Then came a row that made it clear that all such thinking was fantasy.

*His gathering of artifacts greatly enriched the collections of Harvard’s Peabody Museum. By 1890 he had seen and photographed almost all known ancient sites in North and South America, for example, and from his pictures constructed a theory, remarkably similar to that held by twenty-first-century anthropologists, about the migration of the first Americans from the far northwest southward all the way to the west coast of South America, where the hunters-turned-farmers turned hunters again.