The Illustrated Insectopedia - Hugh Raffles (2010)

On January 8, 2008, Abdou Mahamane Was Driving through Niamey...

1.

On January 8, 2008, Abdou Mahamane, the managing director of Radio et Musique, Niger’s first independent radio station, was driving home through Niamey, the country’s capital. Around 10:30 p.m., as he entered Yantala, a suburb on the western outskirts of the city, his Toyota hit a land mine hidden in the unpaved road. The radio announcement was blunt: “Our colleague was torn to pieces.” A woman passenger survived, but with serious injuries.

Karim and I had just got off the bus in Maradi, 415 miles to the east, and were watching the news report along with three or four other guests in the dimly lit hotel bar. “That’s the road I take home every night,” Karim said, shaken. On the large flat-screen TV, a silent crowd stared down at a floodlit crater and the mangled carcass of the journalist’s car. In the studio, seated in front of what looked like someone’s cell-phone photo of the blazing vehicle, a government spokesman was denouncing the Mouvement des Nigériens pour la justice (MNJ) and calling on loyal citizens to root out the evil in their midst. For its part, the MNJ, the Tuareg movement that has been in armed rebellion in the north of Niger since February 2007, accused President Mamadou Tandja’s regime of setting the mines itself to feed the spiraling insecurity and violence and of further entrenching this latest phase of a decades-long conflict by refusing to negotiate.

In the hotel bar, it was doubt, counterdoubt, and pensive silence. This was the first attack in the capital, but just the previous month two people had been killed by anti-tank mines here in Maradi, and four others had been wounded in the town of Tahoua. The month before that, a bus loaded with passengers had been hit outside Agadez, the major city of the north. There was no uncertainty about government hostility to independent journalists—two Nigerien and two French reporters were being held incommunicado for nosing around in the militarized rebellion zone. But who could say whether Abdou Mahamane had been targeted or was simply a chance victim? And in either case, who could be certain of the killers’ loyalties? People are “walking around on tip-toe,” reported the radio, everyone is “afraid of being blown apart.”

Still, as Nigeriens well know, there are many ways of being blown apart and many sources of insecurity and dread. These mines and this fear were just two of the routes by which the unrest was coming home. The first time we met, Karim had given me a concise introduction to Nigerien politics. Welcome to Niger, he said, a large country with a small population, a poor country rich in resources, a weak country with powerful neighbors.

A couple of days before the explosion, the two of us had taken a taxi over the U.S.-funded Kennedy Bridge, which spans the Niger River in Niamey, and walked through the lively campus of the Université Abdou Moumouni. Karim had studied law here until 2001, when the university was closed by student strikes. After that, he left to continue his schooling in Nigeria and Burkina Faso. He has many friends here still, and we stopped frequently to exchange greetings. Groups of young men were gathered in the sunshine outside their dormitories, listening to the radio, talking politics, getting haircuts. Young women strolled past arm in arm.

In a book-filled office on the ground floor of the two-story red-brick Faculty of Science building we met Mahamane Saadou, professor of plant biology. Karim had patiently explained to me how the political instability in the north generated random violence and psychic perturbation, how it held back the national economy by preventing the exploitation of subsurface wealth (uranium and oil), and how it increased the opportunities for geopolitical mischief by France, the colonial power, as well as by Libya and other neighbors. Professor Saadou listened as I described my ideas for this book and Karim explained that we were spending two weeks together talking to people in Niamey, Maradi, and the surrounding countryside about locusts—what these insects do, what is done to them, what they mean, and what they have created here in Niger. When we finished, Professor Saadou told us that one thing created by both land mines and locusts was terror and that they did it not only separately but together.

Because of the political standoff and the proven danger of kidnapping, Professor Saadou said, the internationally funded anti-locust teams in Agadez, close to the mountainous Aïr region and the advancing sands of the Sahara, rarely leave their bases. When they do, he continued, it is only for short visits to the field. They can’t carry out their work, and—because a chain is only as strong as its weakest link—neither, therefore, can the elaborate trans-Sahelian locust-monitoring network, the early-warning system designed to give protection to those adjacent to what is not just a zone of conflict but also a zone of distribution, a point from which the criquet pèlerin, the most destructive of the Sahelian locusts, swarms west and south into the agricultural regions.

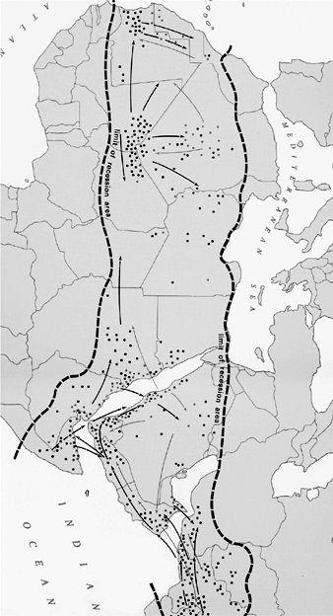

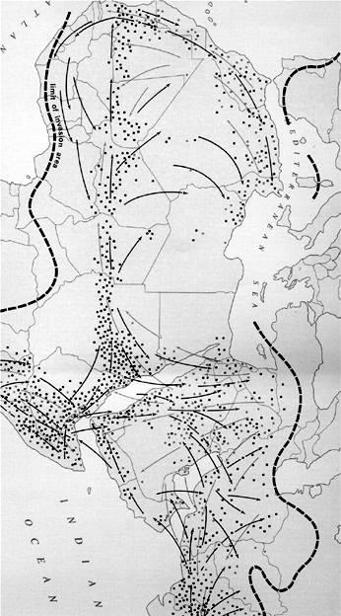

In fact, the professor went on, if you examine the desert locust atlas and look closely at the maps of the insect’s recession area—the zone in which it breeds and aggregates, the zone from which the swarms set out for pastures wetter and greener, a zone that covers about 6 million square miles in a broad belt that runs across the Sahel and through the Arabian Peninsula as far as India, and the only zone in which there is perhaps some slim chance of controlling the animal’s development—you’ll see clearly that many of the most important sites are in places commonly rendered inaccessible by conflict: Mauritania, eastern Mali, northern Niger, northern Chad, Sudan, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, western Pakistan. It’s an extensive, familiar, and in this context, deeply disheartening list.

Across campus, in the Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, Professor Boureima Alpha Gado told a similar story. A historian, Professor Alpha Gado is a leading expert on the famines of the Sahel and the author of an authoritative text on the subject.1 He described how he had used manuscripts from Timbuktu, the ancient center of Islamic and pre-Islamic learning, to determine occurrences of “calamités” dating to the mid-sixteenth century. For twentieth-century disasters, he collected oral histories from villagers, constructing a chronology of the major famines and identifying the critical factors—primarily drought, locusts, and changes in the agricultural economy—and their shifting interactions.

Professor Alpha Gado’s research revealed a rural society grappling with deeply founded insecurities, vulnerable to the vicissitudes of rainfall, human and animal epidemics, and upsurges in insect life. His work invigorated the truism that “natural disasters” act on already-existing social vulnerabilities and inequalities and that “nature” itself (driven in this case by desertification and climate-change-induced drought) is far from innocently natural. He carefully detailed the local social dimensions of these events: the colonial and postcolonial policies that increased the susceptibilities of people in the countryside to famine and reduced their resilience to insect invasions and disease. Notwithstanding the small number of all-too-brief interludes of relative prosperity, he described an everyday state of attrition interrupted by periods of catastrophe, in which the number of deaths has been “incalculable.” Like Mahamane Saadou, he painted a picture of overlapping terrors, of a persistent teetering on the brink, more a condition than an event, a condition with its own rhythms, histories, and enduring effects.

2.

Locusts appear twice in Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe’s famous 1958 novel of British colonialism’s explosion of rural life in the late-nineteenth-century Niger Delta. The first time, “a shadow fell on the world, and the sun seemed hidden behind a thick cloud.” The village of Umuofia stiffens in anticipation of the darkness engulfing the horizon. Or does it?

Okonkwo looks up from his work and wonders if it is going to rain at such an unlikely time of year. But almost immediately a shout of joy breaks out in all directions, and Umuofia, which has dozed in the noonday haze, bursts into life and activity.

“Locusts are descending” is joyfully chanted everywhere, and men, women, and children leave their work or their play and run into the open to see the unfamiliar sight. The locusts have not come for a very long time, and only the old people have seen them before.

At first, there are not so many, “they were the harbingers sent to survey the land.” But soon a vast swarm fills the air, “a tremendous sight, full of power and beauty.” To the entire village’s delight, the locusts decide to stay. “They settled on every tree and on every blade of grass; they settled on the roofs and covered the bare ground. Mighty tree branches broke away under them, and the whole country became the brown-earth colour of the vast, hungry swarm.”2 The next morning, before the sun has a chance to warm the animals’ bodies and release their wings, everyone is outside filling bags and pots, gathering all the insects they can hold. The carefree days that follow are filled with feasting.

But Chinua Achebe’s story is a tale of destruction. Joy becomes unrelenting historical pain. The cloud still looms, and its shadow falls over Umuofia’s future. Pleasures are bound fast to their fatal opposites. Everyone in the village is happily enjoying the unexpected harvest when a delegation of elders arrives at Okonkwo’s compound. Solemnly, the elders decree the killing of the beloved child who is Okonkwo’s ward, a killing that corrodes his family. Years later, when the locusts reappear, Okonkwo is in exile.

It is his friend Obierika who visits him with the news. A white man has appeared in a neighboring village. “An albino,” suggests Okonkwo. No, he is not an albino. “The first people who saw him ran away,” says Obierika. “The elders consulted their Oracle and it told them the strange man would break their clan and spread destruction among them.” He continues, “I forgot to tell you something else the Oracle said. It said that other white men were on their way. They were locusts, it said, and that first man was their harbinger sent to explore the terrain. And so they killed him.”3

They kill him, but it is too late. The vast swarm of white men would soon arrive. There’s no ambiguity in this story. The pleasures are quickly excised. It’s all flat, the flatness of history foretold. The flattening of everyday life among the locusts. Hard to think past these terrors, you might say (with reason). A vast swarm would soon come, and nothing would again be the same.

3.

Mahaman and Antoinette are such good hosts! We’re sitting in their luxuriant tropical yard in Niamey talking about les criquets. We’re trying to specify the exact category of food in which they belong. Everyone agrees they’re a special food. But they’re a special kind of special food, different from the special crispy honey cakes Mahaman just brought back from Ethiopia and insists that Karim and I eat more of. Criquetsare a social food, Antoinette says. Sort of like peanuts, but not a party food. Hmmm. A short silence. Well, texture is important: They’re crunchy! And they’re spontaneous, too. How so? Well, we shop in the open-air markets here, not in the supermarket, so we shop every day. It’s an every-day economy. We see criquets on the market and maybe we think, I’m going to buy some of them! We bring them home and cook them with oil, chilies, and plenty of salt. Sooo delicious! It’s a spontaneous treat. It’s a food for fun, a fun food, a personal, friendly treat. Friends, family. Social food. It’s the kind of food you eat just because you feel like eating it.

It’s a Nigerien food, adds Mahaman. When our daughter is at school in France, she always asks us to send her criquets. It’s the thing she misses most, the strongest taste of home. Yes, Karim agrees, it’s what everyone misses; we sent packages to my sister when she was in France as well. And don’t you remember, he asks me, that’s what the guy this morning selling those rust-colored, crunchy-looking insects on the sleepy market just past the university said too? Fry some in salt and take them back to New York, he said; share them with a homesick Nigerien and make him very happy!

Talking like this, we quickly establish that—like so many foods—criquets satisfy spiritual as well as physical hungers. Eating them is one of those things that makes someone Nigerien. They eat them in Chad too, says Karim, but the quality is not so good. And no one eats them in Burkina, although Nigerien students bring packages from home across the border, and people in Ouaga are starting to get a taste for them. But Tuaregs don’t eat them, someone says, further complicating the national question. And, entering right on cue, closing the garden gate behind him with a broad smile, the director of LASDEL, the research institute that is hosting my stay, says yes, that’s right, we Tuaregs don’t eat small animals at all!

A special food, we all agree, and in the markets in Niamey and Maradi, this is obvious. The United Nations calculates that 64 percent of the population of Niger lives on less than the equivalent of U.S. $1 per day. The regime struggles to maintain its position at the helm of the state. How can the administration capture the resources it needs to maintain its popular base when 50 percent of its potential annual budget goes directly to the international development organizations? The government disputes the U.N. figures, as well as the 2008 human development index score of 0.370, which placed Niger 174th out of the 179 countries measured, as well as the Save the Children Mothers’ Index of 2009, which ranked the country 158 out of the 158 countries surveyed and cited 44 percent of its children as malnourished, the life expectancy of its women at fifty-six years, and a figure of one in six for the number of its infants expected to die before their fifth birthday. In the media, those numbers are taken to be both a national shame and—more assertively—an expression of international hostility.4 Yet, however you look at it, in this situation the rhetoric of crisis does not work to the government’s advantage. Some of those figures may be debatable in a largely rural and far from straightforwardly cash-based economy. But it’s abundantly clear that few people outside development workers, successful merchants, and the political class have much income to circulate.

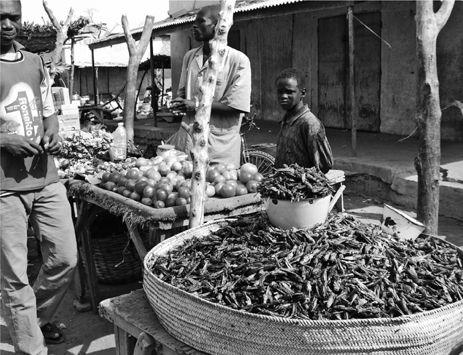

Nonetheless, in January 2008 traders in Niamey’s many markets were selling enamel basins of dried criquets for 1,000 CFA each, well over double the United Nations’ estimate of most people’s daily income.5Criquets are a special food. And an expensive one, too.

January is not a good month in this business. With Eid al-Adha falling in early December this year and then Christmas and the celebration of the new year, there’s little extra cash for criquets, and people buy only in small amounts, just fractions of the enamel tia measuring bowl. It’s not only money that’s tight. There aren’t many insects in circulation either. January turns out to be a long way from September, when supply peaks at the end of the rainy season and the markets are full of locust sellers and the price falls as low as 500 CFA. Now, as we soon find out, criquets are scarce in the villages, and in another month no one will be bringing them into town.

We talked to all the insect-selling stallholders we could find in Niamey. Some of them buy their stock in nearby market towns like Filingué and Tillabéri, some buy from traders on larger markets in Niamey, and some simply buy wholesale from neighboring stalls in the same market. Most, though, said their criquets come from Maradi, and all of them told us to go there. That’s where these animals are sent from, that’s where you’ll find the collectors out in the bush early in the morning, that’s where the big suppliers are based.

I’m enjoying running around Niamey with Karim. There’s so much to see and learn here. I love the markets, discovering with a shock that I recognize only a tiny proportion of the vegetables. These plants got here through an evolutionary history I can’t begin to imagine! And then there are products for sale that might equally be animal, vegetable, or mineral for all I can tell. I can’t come close to guessing their purpose until Karim explains that these neatly stacked mottled-glass marbles are globules of tree resin, which make a superior chewing gum; that those dark, craggy tennis balls are crushed and compressed peanuts used for sauce; that those bottles of murky liquid are full of contraband gasoline smuggled in from Nigeria.

Karim and I keep each other busy visiting the markets, the university, and government offices, meeting all kinds of interesting people, not just scholars and traders but state officials, development workers, insect scientists, insect eaters, and talkative fellow passengers in communal taxicabs. We make the most of Mahaman and Antoinette’s hospitality. But this can’t last. After just a few days, we find ourselves huddling in the crowded bus station at 3:30 a.m. We’re cold, sleepy, and a little bad tempered, and it feels as though the bus to Maradi will never arrive.

4.

We spent those first few days in Niamey chasing after Achebe’s paradox: How could these animals bring both feast and famine? How could they be harbingers of both life and death, bearers of both pleasure and pain? Our contacts and our conversations multiplied, and as they did, our questions changed. Soon, we were wondering if—as Boureima Alpha Gado had tactfully suggested—this was less a paradox than a confusion, if maybe there were more animals here than we realized, if perhaps they weren’t the animals we thought they were, if maybe we weren’t always talking about the same ones, if perhaps some of this was a problem of translation. In French, everyone called them criquets. In Hausa, they were houara. We’d thought we were talking to people about locusts, but now we weren’t quite so sure.

AGRHYMET, an agricultural research organization sponsored by Africa’s nine Sahelian countries, has offices and a library in Niamey, just past the university. The helpful and generous staff members gave us a set of attractive pocket-size paperbacks, including the Vade-Mecum des criquets du Sahel by My-Hanh Launois-Luong and Michel Lecoq, a field guide to more then eighty regional species. Some of these, such as the criquet pèlerin, the criquet migrateur, the criquet nomade, and the criquet sénégalais, are famously destructive and have long been the object of intensive research and control measures. Others, listed by their Latinate species names, are included simply because they’re abundant or, conversely, because they’re unusual.6

The Vade-Mecum identifies nearly all the criquets of the Sahel as members of the Acrididae family, the short-horned grasshoppers. Among the approximately 11,000 known species of grasshoppers, 10,000 are in the Acrididae family, including all the locusts (about 20 species). What is it that makes the locusts special? Biologists distinguish them from the other acridids by their ability to change form in response to crowding. Schistocerca gregaria—the criquet pèlerin, the desert locust, the eighth plague of Egypt—is perhaps the most characteristic of all. The harmless solitary insect is thought to be stimulated to enter a gregarious phase by the increased contact that accompanies high population density, a density which results from two coinciding but not unusual factors: higher than average rainy seasons, which encourage the insects to reproduce, followed by dry periods, which shrink its habitat, limit its food resources, and encourage it to travel.7 In phase transformation, the rapid and reversible changes in the animal’s morphology (wider head, larger body, longer wings), life history (earlier reproduction, reduced fecundity, more rapid adult maturation), physiology (higher metabolic rates), and behavior are so radical that for a long time insects in the two phases were thought to be distinct species.

The gregarious nymphs—the hoppers—form into bands of thousands or even millions of individuals and begin to march. As they make their way across the desert, other hopper bands arrive and merge with the original column. They can cover tens of miles heading in a straight line, and as they march, they pass through their five instars, stopping their journey only when they finally molt to become the adult insect.

At a critical density, the adult locusts take to the air. Until recently, it was thought that the Sahelian swarms were carried along the intertropical convergence zone to areas of rainfall favorable for reproduction. It’s now clear that rather than being passively transported on the current, the animals control their route and direction: they navigate, altering their course and orientation both collectively and individually, often flying against the wind rather than with it and stopping at attractive feeding areas as they go. It has also become clear that swarming is principally a foraging activity rather than a migratory one and that long-distance migration is more commonly undertaken by solitary adults flying huge distances at night. It is this complex combination of talents—rapid reproduction and aggregation, long-distance flight, mass foraging, and individual migration—that allows the criquet pèlerin to find and exploit temporary patches of favorable habitat in an overall highly marginal environment.8

The scale of the swarm is well-known but still hard to comprehend. The University of Florida Book of Insect Records (a wonderful project!) describes one in Kenya in 1954 that contained about 50 million insects in each of the seventy-five square miles it covered, a total of 10 billion animals.9 These are vast numbers and vast appetites. One locust can consume the equivalent of its own body mass in vegetation every day; only 0.07 ounces perhaps, but multiply that by 10 billion and calculate the consequences. Somewhere on the BBC website, I read the impressive statistic that one ton of locusts, just a small patch of a swarm, eats the same amount of food in twenty-four hours as 2,500 people (but which people, we might wonder?). It’s obvious but still worth stating that the impossibly high numbers are compounded by the huge distances the insects travel (up to 2,000 miles in a season) and the destruction they bring over this enormous area, as well as by their willingness and capacity to eat almost anything, not only crops but plastics and textiles. Only subground crops—tubers, for instance—are safe.

In English, the linguistic distinction between locusts and other grasshoppers is emphatic.10 Locust conjures up a tight set of referents linked to rapaciousness, fear, and suffering. By contrast, grasshopper—at least outside the anti-acridian literature—is rarely menacing. Think of David Carradine in Kung Fu or of Keats’s little friend who “takes the lead / In summer luxury” and is “never done / With his delights.”11

There’s nothing in the popular use of the word grasshopper that calls up the ravageurs. But there should be. Fearsome as they are, locusts do not have a monopoly on terror in the Sahel. Even on insect terror. The other most-dreaded criquet in Niger is a grasshopper, Oedaleus senegalensis, the criquet sénégalais. Described as a nongregarious grasshopper because it does not change phase, it nonetheless forms hopper bands and loose adult swarms and can migrate more than 200 miles in one night.12 The criquet sénégalais has been responsible for devastating invasions of Nigerien farmland and pastureland on a scale comparable to that of the criquet pèlerin. Like the desert locust, this grasshopper is a continual threat to Sahelian farmers. Unlike the locust, it breeds in areas close to cropland and has a development cycle tightly coordinated with that of millet. It’s a persistent, debilitating presence, rarely absent from the fields. Indeed, it’s often argued that the use of pesticides to control insect outbreaks has increased grasshopper populations by removing their predators. “Grasshoppers,” wrote the entomologist Robert Cheke in 1990, “afford a much greater long-term and chronic menace to agriculture than do the classic locusts.”13 People in the countryside told us that even when the criquet sénégalais and its allies aren’t swarming, there’s terror in the slow death caused by their constant undermining of everyday life and future horizons.

Yet, it is still the case that the bulk of research and management funding for securing crops against agricultural pests is aimed at the criquet pèlerin. It’s partly a taxonomic disorder—a question of naming and its consequences—that grasshoppers, some of whom are identical to locusts in all significant respects, have been cast into the shade. Whereas the swarming of the criquet pèlerin has long provoked the full-blooded apparatus of humanitarian intervention, until quite recently farmers’ losses in their struggles with the Sahelian grasshoppers were understood only as part of the cost of growing food under marginal conditions.14 This is also partly a problem of temporality. And of vision and visibility, too. A long-term war of attrition hardly lends itself to the campaign politics of disaster relief. An upsurge of locusts is a crisis, with all the international media and aid-agency mobilization that a crisis entails. It is a “plague,” driven by the locust’s perverse glamour, its charisma and celebrity, generating spectacular news and both the obligation for governments to be seen combating an iconic foe and the opportunity for international agencies to step in to the administrative void.

The two most common Nigerien terms for this animal are expansive. Both criquet (in French) and houara (in Hausa) describe a motley community of insects whose commonalities far exceed their differences. Karim and I never systematically mapped this community’s boundaries, nor did we map differences between the terms, but each comfortably enfolded all the insects we were talking about: the ones eaten at parties, the ones collected in the bush, the ones caught up in children’s games, the ones sold in markets, the ones sent to homesick relatives, the ones that swarm and ravage spectacularly, the ones that don’t swarm but still ravage, the ones with polymorphic phases, the ones without, the medicinal ones, the magical ones, the ones that offer a glimpse of financial possibility, the locusts and the other grasshoppers.

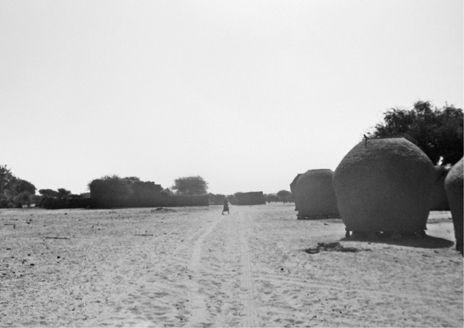

One morning in the village of Rijio Oubandawaki, a dusty three-hour drive north of Maradi, a crowd of men and boys came up with the names of thirteen different houara in just a few minutes. As it’s women who collect these animals, who knows how many more we’d have learned if they’d been back from the fields. Eleven of those thirteen houara were edible. Three of them were considered especially dangerous to crops. Only one was a swarming insect. Some of the men in this big village, with its clusters of low adobe houses, its narrow lanes bordered with woven fences, its open sandy plazas, and its large concrete schoolhouse, remembered the arrival of those swarming houara in their youth. How could they forget? The insects stripped the fields, invaded the houses. Could they have been the criquet pèlerin? Or perhaps the criquet sénégalais? Or perhaps it was the criquet migrateur, once a source of terror in this region but now largely neutralized by environmental changes in its outbreak zone in Mali. It would depend on when the animals appeared. From 1928 to 1932, it was the criquet migrateur; from 1950 to 1962, the criquet pèlerin; from 1974 to 1975, the criquet sénégalais.15 Whichever it was, they told us categorically, those particular houara have never been here since.

The biologists we met in the cities couldn’t match the animals’ lively names—chief’s knife, from the kalgo tree, sorcerer houara, radada (an onomatopoeia)—with their French or Latinate equivalents. They couldn’t even help us identify the dark ones called birdé that everyone in Rijio Oubandawaki loves to eat, which eats all the medicinal plants so is itself a strong medicine, but whose appearance in the fields is nonetheless a source of dread. Of all the criquets we encountered, birdé is the one that seems to conform most closely to Achebe’s paradox. We suspected it was Kraussaria angulifera, a well-known swarming grasshopper that combined with the criquet sénégalais in massive outbreaks across West Africa in 1985 and 1986 and AGRHYMET’s Vade-Mecum describes as among the most dangerous ravageurs of millet in the entire Sahel. Flanked by pesticide posters in his office at the anti-acridian section of the Maradi Direction de la protection des végétaux, Dr. Mahaman Seidou gave it a second life as one of the two most popular insect food species in Niger.

Nonetheless, we were starting to think of the houara as more protean than paradoxical: many selves, many beings, many lives. Still, here and now, in this place, at this moment, its identity seemed profoundly fixed. Locusts or not, swarming or not, food or not, income or not, they cast a shadow on the land. The facts, even if not completely precise, were unavoidable. Approximately 20 to 30 percent of the Nigerien agricultural crop, some 450,000 tons, a total greater than current estimates of the country’s food deficit (the difference between what the population eats and what it grows), is lost annually to insects and other animals, mostly birds. Here in the Maradi region, where conditions are even more favorable to insects than elsewhere in the country, that figure is closer to 50 percent.16

Perhaps, though (we had to wonder), it wasn’t only the weight of the facts that cast this shadow over our conversations. Perhaps the depth of the shadow was also an artifact of our interest and of the resources we embodied in a country dependent on and habituated to international aid workers. That day in Rijio Oubandawaki, life’s pleasures and the houara’s possibilities—the food, the games, the cash in hand, the knowledge—slipped quickly out of sight. In other circumstances, it might be satisfactions that come to the surface. But with such a brief visit, with so little earned intimacy, with just the appeal and the desire on all sides, the life most visible was the obvious—the houara most visible was the obvious—the one that multiplied the manifold insecurities of a profoundly hardscrabble human existence.

“I have a question,” one man said to me as we were leaving. “Can you tell us some techniques we can use to control these houara and protect our millet?” How could I respond? “I’m afraid I’m not really an expert in that kind of thing,” I said awkwardly, adding that when I returned to Niamey the following week, I would immediately visit the central office of the Direction de la protection des végétaux and tell the officials about the problems people here are facing. Everyone fell silent. The men with whom we’d been talking thanked me courteously but said I should understand that there was really no point in doing that.

Fifteen years ago, the questioner explained, a team of agricultural-extension workers had come to the village. They trained people to use pesticides and left a supply for the residents’ use. Everyone applied the chemicals as instructed and was happy to see that they worked: insect damage was significantly reduced, yields increased, and there seemed to be no harmful effects on crops, people, or other animals. Soon, though, the chemicals ran out, and fifteen years later the stock has still not been replenished. Nowadays, he continued as we all listened attentively, the only people who use pesticides in this village are the rich farmers, those with more than twenty-five acres, who can afford to buy chemicals privately. The houara avoid their fields and concentrate their appetites on the rich men’s less fortunate neighbors. Every year the insects and birds (those terrible birds!) eat our millet, our sorghum, and our cowpeas; sometimes they eat half our crop or more. We stretch wire for the birds, and we set fire to the houara. We burn the birds, too. But none of it helps. He lapsed into quiet and another man in the group spoke. Actually, he said, you should go to the ministry. When you do, if you look hard enough, you’ll find thick folders of paperwork about this village. You should go, but you shouldn’t bother talking to anyone about us. You shouldn’t imagine they’re not aware of the situation here. Whatever else is going on in the capital, it’s not ignorance.

5.

The bus arrives and we clamber aboard. With the hugest red sun rising ahead of us, we’re soon barreling out of Niamey and across the baked landscape, its flatness punctuated by low rounded hills and sharp lateritic escarpments. For the next few hours, the two-lane highway is lined by ocher villages filled with family compounds of rectangular mud-brick houses. Graceful onion-shaped granaries overflow with sheaves of millet from the recent harvest. People sit outside their homes or at stalls along the road. Men build and renovate walls and fences, repair the granaries, hoe fields. Women thresh tall heaps of grain, pound millet for porridge, gather around village wells, carry large bundles of firewood or millet stalks, their dazzling cotton cloths billowing as they walk. Children collect wood too, or tend other children or herds of goats. We stop briefly to buy food in the crowded bus station at Birni N’Konni and then continue east, ignoring the turning that cuts north to Tahoua, Agadez, and the uranium town of Arlit. From this point on, everything feels a little greener, a bit more prosperous: large herds of long-horned cattle, flocks of camels, their front legs loosely bound to stop them from straying too far too fast, droves of donkeys, more granaries, more fields, and the startling dark splash of irrigated onion patches.

Maradi hums with commercial energy, but its position at the hub of Niger’s economic life dates only from the end of the Second World War. Because of its geographic location and an inability to secure its supply lines, the town was excluded from the great trans-Saharan caravan routes that for centuries linked Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and other Mediterranean ports first to Zinder, Kano, and destinations close to Lake Chad, and then to the rest of Africa. This trans-Saharan trade supplied the eighteenth-century Hausa city-states, commercial powerhouses that in turn supplied gold, ivory, ostrich plumes, leather, henna, gum arabic, and, most lucratively, sub-Saharan slaves to Tuareg and Arab traders, who carried them north, returning from the coast with firearms, sabers, blue and white cotton cloth, blankets, salt, dates, and the multi-purpose mineral natron, as well as candles, paper, coins, and other European and Maghrebi manufactured goods.17

By 1914, the British rail network through Nigeria had reached Kano, close to the border with Niger. It was now both cheaper and safer to send goods by train to Lagos and the other Atlantic ports than to ship them north on the cross-desert camel trains. Taking advantage of the decline of the caravans and the sudden access to transportation, the French administration pushed aggressively to provide the Maradi Valley with the initial capital and infrastructure needed to cultivate groundnuts for the colonial oil market. By the mid-1950s, Maradi was competing as a regional center for a crop that had been strongly commercialized by the French in Senegal and elsewhere in their West African colonies but until then had barely taken hold in Niger. Forced to pay colonial taxes in cash—and drawn to the new European trading houses selling imported goods—Maradi’s farmers brought more and more land into groundnut cultivation and initiated two dynamics that would prove devastating during the extended drought and famine that lasted from 1968 to 1974: the undermining of already-fragile food security through the large-scale substitution of groundnuts for staple crops, especially millet, and the encroachment on and effective privatization of grazing areas used by Tuaregs, Fulanis, and other pastoralists, who, pushed with their animals onto increasingly marginal lands, would make up the significant majority of famine victims.18

The border that split Hausaland between French-ruled Niger and the British Protectorate of Northern Nigeria was fixed in a series of conventions agreed to by the two colonial powers between 1898 and 1910. Insecure about the transborder loyalty of their Hausa subjects, the French funneled their patronage to the Djerma of western Niger, moving the capital from Zinder to Niamey in 1926. “While roads, schools, and hospitals were gradually introduced [by the British] into Northern Nigeria,” writes the anthropologist Barbara Cooper, “the French permitted Maradi to languish as a neglected backwater in a peripheral colony, where infrastructure developed fitfully if at all.”19

The effects of these policies were, predictably, not quite as intended. Even though precolonial Hausaland had been riven by violent rivalries, the common experience of colonial exaction under both British and French rule, plus the persistence of cultural, linguistic, and economic connections, created powerful cross-border identifications that continue to this day. One mark of this linkage is the emergence in Maradi of the alhazai (from the Islamic honorific Alhaji—he who has completed the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca), powerful Hausa merchants who began their careers in the groundnut industry and the European trading houses but rapidly diversified to exploit the opportunities for commerce, licit and illicit, offered by the border. As Cooper notes, it was the ability of the alhazai to capitalize on British investments in northern Nigeria—such as the rail link to Kano—that propelled them to prominence and allowed them to weather such crises as the famine of 1968-74 (from which many profited handsomely) and the devaluations of the Nigerian naira in the 1990s.

The alhazai are also lively participants in the global Islamic geography that links Maradi to Egypt, Morocco, and other sites of higher education, and to Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and other centers of big capital. And they are conspicuous in the resurgent Islamic networks that tie the city to the twelve sharia-governed states of northern Nigeria. Recalling his experience as a leftist student activist confronting the rise of a newly politicized Islam in the university, Karim predicts that the young urban intellectuals leading the Islamist organizations will take power in Niger within twenty years. Their discipline, probity, and commitment has a powerful appeal, modeling a future radically distinct from the remoteness and opportunism—the lack of ideology, as Karim puts it—of the politicians in Niamey and the debilitating combination of ineffectuality and neocolonial authority that has come to characterize the aid organizations.

Discourses of political and moral decadence easily merge. The riots that shook Maradi in November 2000 were led by Islamist activists protesting the Festival international de la mode africaine, a fund-raising fashion show backed by the United Nations that drew leading designers from Africa and overseas. Demonstrators denounced single women as prostitutes, targeting them in the streets and in a refugee village to which many had fled from prior Islamist violence in Nigeria. Rioters torched brothels, bars, and betting kiosks. They invaded Christian and animist compounds.20

People in Niamey point to signs of change in public culture: stores that just a couple of years ago stayed open during Muslim prayers now shutter; large numbers of women on the university campus now wear veils. Maradi is in the vanguard of this complex struggle among “reformist” and “traditional” Muslims, evangelical Christians, and secular Nigeriens. Karim tells me it’s a very different place from when he lived here in the 1990s. Even so, one evening we’re taken by surprise in the city’s giant open-air movie theater when our undubbed, unsubtitled Hindi-language Bollywood gangster film cuts without warning into cheap hillbilly porn that someone has spliced into the pirated DVD. A thick sexual silence descends on a theater that moments before had almost as much life in the all-male audience as it had on-screen. But the surreal effect soon wears thin, and we head off to our hotel on the back of zippy motorbike taxis under starry black skies. When we arrive, Karim tells me that (despite the theater) the Islamists are the future now. With international development and its version of modernity discredited, with the nation in tatters, with no alternatives in sight, time is on their side. When I reply that I didn’t come all this way to write a lament for Africa, he offers a quote he attributes to Lenin: The facts, he says, are unavoidable.

6.

January is as slow a month for criquets here as in Niamey. Yet, passing through the fortresslike gate of the Grand Marché, we’re right away in conversation with a friendly young guy who sells some houara here but mostly exports to Nigeria. The Nigerians look for insects from Maradi because they know that farmers in this area don’t use pesticides, he tells us. We ask where he gets his animals and he calls to a man sitting chatting at the back of the stall. Hamissou is a supplier with whom the owner of this stall has a long-term contract. He shyly describes how he’s been traveling through the villages north of Maradi on his motorbike for ten years buying millet, bissap (hibiscus flowers), and houara.

Two days later there are four of us: Karim, Hamissou, Boubé (who usually drives for Médecins Sans Frontières), and me. We’re heading fast but cautiously—because of land mines—out of Maradi along a red dirt road so straight it seems it will never end. Hamissou is next to me in the backseat, dressed all in white, his cotton scarf thrown across his face against the dust.

Visiting villages with Hamissou was a pleasure. Everyone was excited to see him. His arrival generated laughter and excitement. Men jumped up to playact wrestling with him. They affectionately made fun of his shyness. His trade was a happy, relaxed affair with no economy of distrust.

That morning he took us into the bush to meet women collectors. They’d left their village after the 6 a.m. prayers, and when we caught up with them four hours later, they were far from home. They showed us where they find the houara under low shrubs, how they poke at them with millet stalks, catch them in one hand with swift, sure movements, snap the back legs of the lively ones to stop them from jumping, and secure them in a cotton pouch. If this were September, they said, they’d be collecting pounds every day, making 2,000 or 3,000 CFA from Hamissou and still having a good quantity left to eat. Houara replace meat, they said, reminding me of the conversation in Mahaman and Antoinette’s yard in Niamey. They’re full of protein and—also like meat—they’re not something you eat every day (or, if you want to avoid vomiting and diarrhea, too much of). They’re delicious fried with salt or ground up to make a sauce for millet. In September, there are so many out here in the fields that we bring the children with us to hunt. But now, in January, it’s too cold in the mornings for children, and there aren’t any insects anyway. Look at this sad collection: it takes two days to fill this pouch, and it sells for just 100 CFA. Even the higher price this time of year doesn’t compensate for the poor supply.

If the returns are so low, why spend all these hours in such backbreaking work? I asked, stupidly. An older woman responded, not troubling to hide her scorn: Because we’re hungry. Because we have no money. Because we have to buy food. Because we have to buy clothes. Because we have to stay alive. Because in one month we won’t have even these few insects. Because there’s nothing else we can do to make money at this time. Because it’s something, and doing something is better than sitting at home doing nothing.

She continued: Sometimes there are years when the houara don’t arrive at all. But when they do, they help us build capital. With the proceeds from collecting, we can buy cooking oil, plastic bags, and everything else we need to sell masa, deep-fried millet cakes. With the proceeds from that, we can save a little more, buy our children things they need, create a little security. There are years when so many houara come to the village, she added, that we can even buy a cow. But what we can’t do is store the surplus against the times of hunger. They keep—that’s not the problem—but we can’t do without the cash.

She turns back to catching insects under the shadeless sun. The rest of us follow suit and are soon scrambling around chasing houara in the dust. And what I remember best about this is that Boubé was really good at it, that he kept going long after Karim and I had given up, that he really didn’t want to leave, and that in no time at all the rest of us were standing out there under that everlasting blue sky watching him digging in the bushes and laughing at his success.

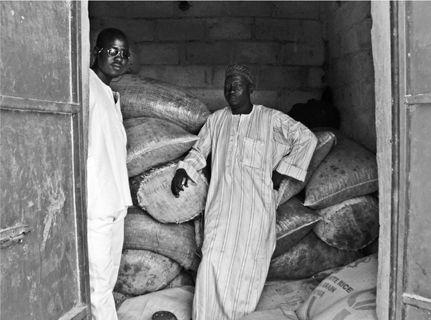

A few days later, there were again four of us passing through the police roadblocks and bouncing along the red road north from Maradi. This time, Hamissou was busy elsewhere, and we were accompanied by Zabeirou, an energetic presence in the front seat next to Boubé, explaining in a stream of Hausa, French, and English how he had become the largest criquet merchant in Maradi, if not in the entire country.

From 1968 to 1974, a savage drought and famine, compounded by outbreaks of Schistocerca gregaria, destroyed Niger’s groundnut economy. Hunger forced farmers to abandon export cropping and return land to subsistence foods, the displacement of which had so undermined their security. Across the Sahel, between 50,000 and 100,000 people died. In Niger, groundnut production plummeted from 210,541 tons in 1966 to 16,535 tons in 1975.21

But by the mid-1970s, some of the world’s largest deposits of uranium, discovered by the French atomic energy commission in the Aïr region, were filling the fiscal void. At its height, uranium provided well over 80 percent of the country’s export revenues and stimulated a national economic boom. But by the early 1980s, following the meltdown at Three Mile Island and the success of the anti-nuclear movement in Europe and the United States, the price of uranium began its long fall, a slump from which it is only now emerging.22 Production of uranium in Niger collapsed along with the price, once more throwing the economy into a revenue crisis and even further on the mercies of the multilateral donor agencies and their punishing financial prescriptions.

At the beginning of this cycle, the uranium enterprise SOMAIR—a subsidiary of the French nuclear conglomerate COGEMA—built a new mining town out in the desert 150 miles north of Agadez. This was Arlit, called Petit Paris for its expat-focused amenities, such as supermarkets stocked directly from France. It was here that Zabeirou had worked as a laborer until 1990, when he left with a payment of 150,000 CFA (something like $550 in those days). He moved back to Maradi and, once there, started to study the markets. He quickly saw that there was a high demand from women for criquets and that—unlike other popular goods—there were no big operators working the trade. The alhazai of Maradi had failed to step in, and business was dominated by petty entrepreneurs.

As he tells it, Zabeirou moved decisively to become Niger’s first serious criquet merchant. Armed with his Arlit capital, he built up his stock by buying all the animals he could from rural collectors. Once he’d cornered the market, he slashed his price deep enough to force out the competition. With his monopoly in place, he raised his prices again and soon recovered his losses.

Nowadays, the competition is more serious and Zabeirou’s business more elaborate. He has a network of informants scattered in towns and villages around Niamey, Tahoua, and Maradi and across the border in northern Nigeria whose job is to seek out houara in times of scarcity. He also has buyers, each with a budget of 300,000 CFA, whom he sends out from Maradi and Niamey to procure in villages and markets. It’s a wary world. Zabeirou keeps his sources secret. Often, he keeps his own location hidden too, moving around clandestinely, letting people think he’s in Maradi checking on supply when he’s actually doing business in Niamey. It’s a wary world, but it pays off: there have been times when he has made 1 million CFA in a week.

When he is in Maradi, Zabeirou is most likely to be at Kasuwa Mata, the Women’s Market, a mostly wholesale market on the northern edge of the city dominated by women traders. Kasuwa Mata is a staging area for goods arrived from the countryside. From here, they go to the Grand Marché and other outlets in town, to markets elsewhere in Niger, and to buyers in Nigeria. Zabeirou has a well-stocked stall here, a destination for middlemen like Hamissou and for women collectors arriving from their villages with houara for sale.

He has four resale options: he can retail directly from his stall; he can wholesale to traders in Kasuwa Mata and elsewhere in Maradi who then resell in the local markets; he can send sacks by truck for his employees to sell in Zinder, Tahoua, or Niamey; or he can take the houara to Nigeria. At this time of year, a time of high prices and scarce supply, many of his customers are women who prepare the animals for their preteen children to sell from metal trays balanced confidently on their heads. It’s a popular spicy snack, tiny packs of five or six insects for 25 CFA that other children buy outside their elementary schools or bigger packs for 50 CFA that the drivers of kabu-kabu, motorbike taxis, stand crunching as they wait for their next fare.

Zabeirou led us to a storage facility behind his stall and showed us some of his stock. Sacks and sacks of criquets, several months’ supply, 2 million CFA worth, he said. He would add to them over the next few weeks—until there were no more in the countryside and the price started to rise. Then he’d release them to the market. Good business, we all agreed.

Three wives and ten children. A large house with a walled yard close to Kasuwa Mata. Zabeirou’s prosperity was matched by his expansive manner. Karim and I were cautiously pleased that he’d decided to adopt us. After a couple of hours on the road, we stopped in the market town of Sabon Machi, where he insisted on buying us a breakfast of masa and sweet tea. Another couple of hours and we arrived in the village of Dandasay.

Zabeirou’s brother Ibrahim is one of the three schoolteachers here. He has a quiet and gentle manner quite different from that of his older sibling. As we talk, I’m thinking what a sympathetic teacher he must be. He is telling me that parents in the village have so little cash that he is scared when he sometimes has to ask them for 10 CFA for supplies. He introduces me to his colleague Kommando, a strikingly tall, thin man with a similarly kind demeanor. Karim figures out that Zabeirou hasn’t been here before. Off-road on the last stretch of the journey to Dandasay, we’d been forced to stop for directions more than once. As we pulled into the village, he’d ordered the children who raced to greet us to run and tell their mothers that he’s here to buy houara.

It turns out to be a complicated day. Assuming the twin roles of tour guide and impresario, Zabeirou has decided we need to see houara being prepared for sale. He begins to organize the performance but has barely started rounding up likely women when he discovers that the collectors have yet to come back from the bush and no one here has any fresh criquets. In the meantime, women alerted by their children have emerged from their houses with small bags of insects. Normally, they take these to the nearby market in Komaka or to Sabon Machi, bigger and further away, or, on a Friday, to Maradi, much bigger and further still. Normally, Zabeirou would have buyers waiting for him in those markets. But today is a special day, and he sets up shop behind our truck and starts to deal.

He hasn’t got very far when a group of men arrives to invite us to a cebe, a baby’s naming ceremony. It’s on the far side of the village, so Zabeirou suspends operations, and we make our way through the narrow sandy lanes to where the first row of chairs has been vacated in front of a thatched patio beside a small house. The imam takes his place on a mat among a group of senior men, and the audience watches, periodically joining in to recite the blessings, as the dignitaries move through the solemn ceremony. It’s calmly meditative, and everyone is focused on the chants with a quiet intensity. But as the service proceeds, I gradually become aware of what sounds like a spirited debate going on behind us. I turn around, and there’s Zabeirou in position again at the back of the truck, bargaining with a line of women waiting to sell their houara.

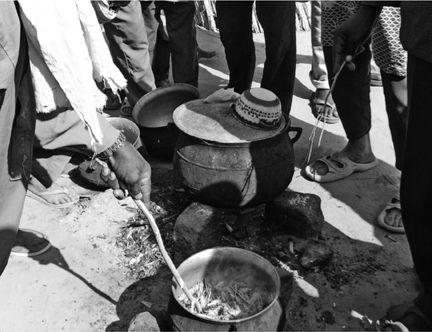

We’re treated too well here. After the ceremony, the father of the child invites us all to eat first, before his other guests. Karim, Boubé, Zabeirou, Ibrahim, and I enter a small round building and are served an elaborate meal of millet and meat. We reemerge to hear that the collectors have returned from the bush. A fire is hastily lit outside a nearby house, and a young woman (decidedly unimpressed) begins heating a large pot of water under the gaze of what is by now a sizable crowd. As the scene develops, Zabeirou offers detailed National Geographic-style commentary for our benefit and repeatedly cautions me not to miss the opportunity to take photos. When the houara arrive, he dumps them in the boiling water, takes the young woman’s stick, and not letting up his patter, shoves the flailing animals deep into the pot. The women who perform this mundane operation on a daily basis are shut out of the circle and wander off to more compelling things. The men take turns poking at the pot, closely watching something that they, too, must have seen untold times but takes me entirely by surprise: as they churn in the roiling water, the tan-colored insects rapidly turn pink, resembling nothing so much as cooked shrimp and, in that moment, opening an unlucky door into other universes of possible fates.

The insects boil for thirty minutes. Meanwhile, Ibrahim and I chat with the maigari, the headman of this large village, and with a few other men. They tell us that the criquet pèlerin was here sixty years ago but has not been back since. These older men remember the destruction but—like the men in Rijio Oubandawaki—it’s not something they dwell on. Rather than this once-in-a-lifetime apocalypse, it’s the less exotic houara like the birdé, with their grinding away at everyday food security, that preoccupy them.

Kommando is part of this conversation, too. As it ends, he tells me that he used to work in a village about sixty miles north of here called Dan mata Sohoua. We should visit, he says. The chief there can tell us about the locust invasion of 2005. It’s quite a story. Just then I spot Zabeirou across the crowd. He has a tia and is using it to measure out the women’s insects. To the sellers’ dismay, he piles the animals high, mounding more and more until there must be as much as 40 percent extra heaped on the basin, which he then tips into his sack. As I watch, I recall how he always gives an additional “social payment” when he sells in Kasuwa Mata, how he piles on varying amounts depending on the status of the buyer (a widow, for instance, may get more), so that the houara spill over the lip of his tia in a gesture of generosity that is, however, somewhat more modest than the one he’s managing today.

The drive back to Maradi is uneventful. Before we leave, the woman who had begun boiling the houara is called back to spread them on a blue tarpaulin so we can watch them dry in the sun. Zabeirou declares himself satisfied with the day’s program. As we approach the city, he asks if I’ll be back soon. I can’t offer a date, and we all slip into our own thoughts. When we reach Zabeirou’s house, his demeanor changes abruptly. Eschewing conventional sentimentalities, he demands payment for his services, apparently forgetting that our outing was conceived under the banner of international friendship and that he has already done rather well from the women of Dandasay. Karim is infuriated, and we enter into testy negotiations, Zabeirou refusing to let us leave until an unhappy compromise is reached.

The three of us drive back across town feeling irritable. But the mood doesn’t last long. Our sense of purpose returns when we decide to follow Kommando’s advice and head out early the next morning for Dan mata Sohoua.

7.

According to the World Bank, the invasion area of the criquet pèlerin extends over 20 percent of the earth’s farm- and pastureland, a total of 11 million square miles in sixty-five countries. Control measures, primarily surveillance and chemical spraying, focus on outbreak prevention and elimination in the recession area, the drier central zone of this region, the 6 million square miles within which the animals mass. The reasoning is simple: once the hopper bands have undergone their final molt to become winged adults and the swarm has taken to the air, the only option is crop protection through upsurge elimination on-site, an option with very low rates of success. Crop protection in the village, Professor Mahamane Saadou had told us, is a mark of the failure of prevention in the recession area. It means villages are saturated with pesticides—some that are banned in Europe and the United States—placing in jeopardy both the members of the village brigades who apply the chemicals (often without protective clothing or adequate training) and the community’s food chain and water supply.

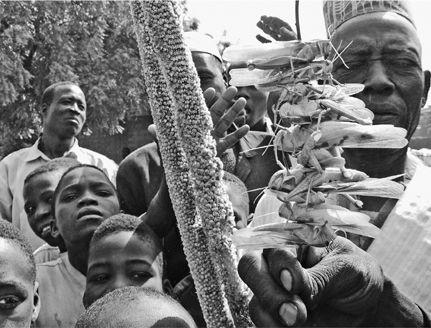

As Kommando had promised, the chief of Dan mata Sohoua was keen to tell the story. The locusts arrived from the west, he said. It was October, just after the rainy season. The millet was fully ripened, but the harvest had not yet begun, and the grain was still on the plants. The timing could not have been worse.

At first there were only a few, the harbingers—as Chinua Achebe has it—sent to survey the land. They appeared around midday. The children came running from the fields to raise the alarm. But none of the adults went to look. They knew it was already too late. By the time darkness fell, the swarm had arrived.

The next morning the village was overrun. The houara covered the ground. They covered the bush. You couldn’t see the ground. You couldn’t see the millet. People tried to chase them away. They used tools, they used their hands, they set fires. They tried to save the millet by picking it from the plant. What could they do but heap the seed heads on the ground? By the time they turned back, the insects were all over them.

On the morning of the second day, the maigari and a group of senior men went to Dakoro, the nearest town, to alert the Agricultural Service. Normally, the maigari told us, the Agricultural Service paid no attention to the problems here. But that day they came. After inspecting the fields, they advised people to pray. There was nothing else for it, they said.

Nonetheless, later that day a plane arrived to spray the area with pesticides. As it flew overhead, the houara took off. At first it seemed as if they were leaving the village, but instead they took aim at the plane. They flew straight for it, enveloping the cockpit, swarming over the wings, trying to force it up and away from the village. The pilot changed tactics. He couldn’t come in low. Instead, he tried to spray alongside the insects, but they scattered and the chemicals had little effect. The animals were disciplined and organized. It was as if they had a commander and were following orders.

As if they had a commander. Every day, they started work at exactly 8 a.m. No, not because it was cold before then. That’s what everyone thinks, that they were waiting for the heat to warm their wings. But, no, it was because they had their workday. Like white people. They started at 8 a.m., never earlier. As it got close to 8, they became restless and ready to fly. The commander gave the order, and they began. When they took off, they flew low, scouring the ground for food, always ready to land. At 6 p.m., they stopped. Like an army with a commander. These animals were intelligent. It was as if they had binoculars. If they left anything, they turned around and came back for it. If one of them was injured, they turned around, came back, and ate their fallen comrade rather than leave it on the road.

There were people who set fire to them in the mornings as the houara massed there waiting for the order. It was a mistake. It was just a provocation. If they managed to kill a sackful like that, they could be sure that double that number would soon arrive to take their place. Everyone stopped going to the fields. When they went outside, they had to cover their faces. Adults stopped children from going into the bush.

On the third day, the locusts left. There was no more millet. They’d taken it all. But they’d left something of their own. Two weeks later, the eggs hatched, and the hoppers emerged from the ground. This time was far worse than before.

A small girl walked across the sand to where we were seated under a generous shade tree. The afternoon air was hot and still. In the distance, we could hear the rhythmic thuds of women pounding millet. The maigari sold the girl a few bouillon cubes. A thin-faced man seated behind a tabletop sewing machine picked up the story as the rest of us, six men and two women, listened.

We’d never seen these houara before, he said. Even people 100 years old had never seen them. We called them houara dango, destroyer crickets. They were bright yellow on the outside, black inside. The yellow came off like paint if you touched them. They were so strange that at first we thought they’d been invented by white people. The old people told the children not to touch them. The goats that ate them aborted, the chickens died. Not from the pesticides, as you might think, but from some tiny insects that lived inside the houara. The chickens and goats weren’t safe to eat. We had to destroy them. The houaraentered the wells. They poisoned the water. Not even the cattle could drink from that water. Someone in another village ate them, and he was sick, vomiting for days. We couldn’t eat them. If we could, there were so many we’d be eating them still.

Now everyone was talking. There was no doubt that the second wave was even more devastating than the first. The Agricultural Service sprayed the hatchlings, but the survivors ate the corpses. There was nothing left in the fields. Whatever the hoppers could eat in the village, they ate. This time, they stayed for three weeks, working their way systematically through the village, consuming everything in their path, even their own dead; yes, that’s right, they left nothing, not even their own dead.

With no millet in the granaries and no harvest to look to, people in Dan mata Sohoua were completely dependent on emergency food aid. Fueled by emotionally charged reporting on the BBC, the situation in Niger and across the Sahel became international news. The specter of famine coupled with plagues of locusts prompted high-profile public appeals in the donor countries. These in turn generated dismayed reaction from the administration of Mamadou Tandja, who watched as this media-driven internationalization gave carte blanche to the nongovernmental organizations to act on behalf of a humanitarian global public, further undermining the state’s already-limited capacity.

For a few weeks, the Médecins Sans Frontières feeding center in Maradi “received more media attention than anywhere on the globe.”23 And, indeed, although it is unclear how severe the situation was in other parts of Niger, for residents of the countryside around Maradi (and for pastoral people in the north), things were significantly more difficult than normal. Oxfam stepped in to Dan mata Sohoua with 400 bags of rice, which arrived just as everyone was debating whether to abandon the village. Dan mata Sohoua became a center of food distribution for people who arrived from all around to collect their ration. Oxfam promised three full consignments, but for reasons unknown to people here, the second delivery was much reduced and the third simply didn’t materialize.

That year of the houara dango, farmers in Dan mata Sohoua had planted seed lent by development organizations as an advance against their crop. When the millet failed, they had few options. One was to appeal to local merchants—from a position of extreme weakness—to convert donated rice to cash to meet their debt. But the rice never came, so the debts deepened (and people were unable even to sell their food aid, a practice that, although reviled by the aid agencies as profiteering, can have its own compelling logic).

Two harvests later, people told us, they still hadn’t repaid the loans. Nor had they paid their taxes since 2005. Just as the Nigerien state is caught in its chronic international dependencies, so people in the countryside around Maradi struggle to access whatever resources might come their way.24 In the long days of hunger after the invasion, farmers in Dan mata Sohoua joined with NGOs in the region to start a banque céréalière, taking grain (rather than seed) on loan and repaying the loan after the harvest. Even in the best of times, the harvest provides little surplus, so the obligation to give some of it away is not a welcome one. But at least in this arrangement there is no need for cash—or for a Zabeirou. Perhaps, says someone wistfully, if the harvests are good, if no more swarms arrive, we’ll be out of this hole in another two years.

8.

On the bus back from Maradi, Karim and I found ourselves sitting with a group of agronomists headed to Niamey for a conference on insect-pest management. They shared with us their ridged sheets of tchoukou—tangy crispy-chewy cheese—and when we all got down to stretch our legs at Birni N’Konni they insisted on paying for sodas. We talked about their work with resistant strains of millet, and I thought back to the conversation Karim and I had a few days before with an enthusiastic young researcher at the Maradi Direction de la protection des végétaux who is developing a biological control of the criquet pèlerin using pathogenic fungi as an alternative to chemical pesticides.

The next morning we went back to the university to visit Professor Ousmane Moussa Zakari, a prominent Nigerien biologist critical of the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization’s efforts at pest control. The FAO has never successfully predicted an invasion of the criquet pèlerin, Professor Zakari said. He calculates that there have been thirteen major locust outbreaks in Niger since 1780, and although the local effects can be overwhelming, the aggregate is less so. Like many of the researchers and farmers we talked to, he regards current control efforts as a failure. The recession area is too large and too inaccessible, the insects are too adaptable, capable of withstanding extended drought and responding rapidly to favorable conditions. He argued that the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on eradication would be better spent elsewhere, helping farmers draw on their own knowledge of pest control, for example, and working with them to develop new techniques, such as interrupting the development of the criquet sénégalais by delaying the planting of the first of the two annual crops of millet.

That same day, as if in a reminder of the complex fragilities with which Nigeriens struggle, a French aid worker was caught in a carjacking in Zinder. She had stopped her vehicle for two men who appeared to need help at the side of the road. They bundled her out of the car and drove off. No one was hurt, but unfortunately for everyone involved, the men had left without realizing that the woman’s toddler was still in the vehicle’s backseat.

I think it was also that day that Karim told me about catching houara when he was little. I think it was that day—although it could have been earlier, as the bus worked its way into the sunset across the plains from Maradi, or it could have been in a taxi at another time altogether, as we drove onto Kennedy Bridge past the U.N. billboard that celebrates the “Rights of the Child,” or it might even have been before we left Maradi, driving back from Dan mata Sohoua along the only road in Dakoro, a road lined with signs for international development agencies (just as the main drag in a U.S. town is lined with signs for motels and fast-food restaurants). Anyway, it was on one of those occasions that Karim told me about catching houara when he was little. It was in the village close to Dandasay where he grew up. It was a favorite game. All the children played. They’d make a light to draw the insects and catch as many as they could, the more the better. There was no shortage, and the winner was the one who caught the most. It was a simple game but a happy one, he said.