Mountain Music Fills the Air: Banjos and Dulcimers: The Foxfire Americana Libray - Eliot Wigginton, Foxfire Students (2011)

DAVE STURGILL

Dave Sturgill’s roots in Piney Creek go back to the time of the Indian. Unlike many of his ancestors, however, he spent a large portion of his life away from the mountaias. After he graduated from high school during the Depression, he began to wander, covering the country from New York to San Francisco. “I got my education by traveling, and of course one of the things I was interested in, even then, was music, so I carried my instrument and played in clubs to make a little money.”

In 1938, he wound up in Washington, D.C., went to school for a year, worked for the Western Electric Company, and then moved to the Bell Telephone Company. He stayed with them for twenty-nine years in Washington, and was a general engineer in switching equipment when he left. He was fourteen months away from retirement, he had a wife and sons, “But my heart never left the hills. This was where I always wanted to be. There were riots in Washington then, and these hills looked so good every time I came down here that I finally came down here and stayed.” He worked for a while in a small musical factory in Nashville that was foundering, then left, came back home, built a shop and dug in. His two sons, meanwhile, had been doing some wandering of their own—one worked for the Evans Steel Guitar Company in Burlington, North Carolina, for a while—but they, too, were circling closer and closer to home. Now they’re Dave’s partners in what has turned into a thriving business in guitars, banjos, mandolins, and dulcimers. Neither Dave, Danny nor John has ever regretted the move. As John said, “Being born in Washington was an accident I couldn’t help. I never did count that home. I spent all my summers down here. Now I’m here to stay.”

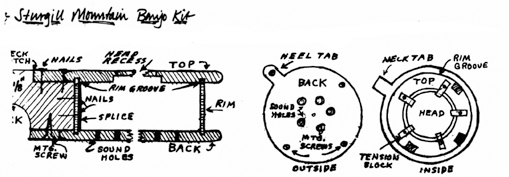

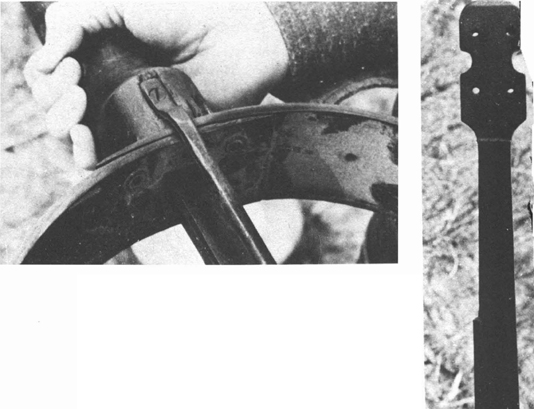

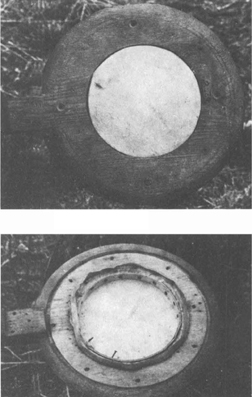

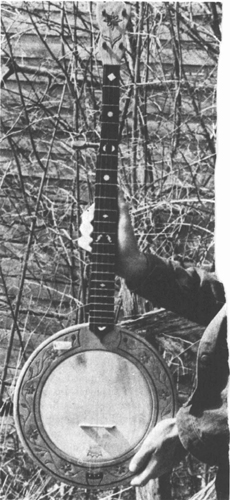

ILLUSTRATION 56

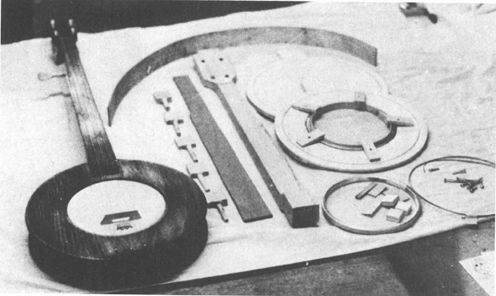

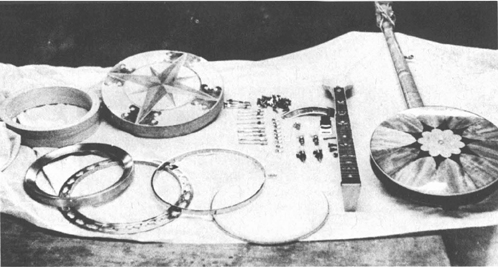

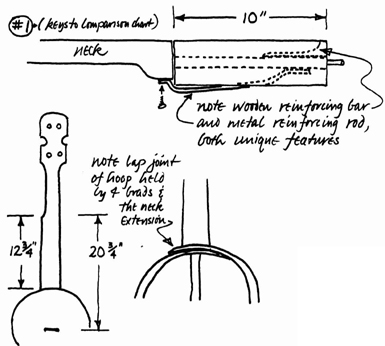

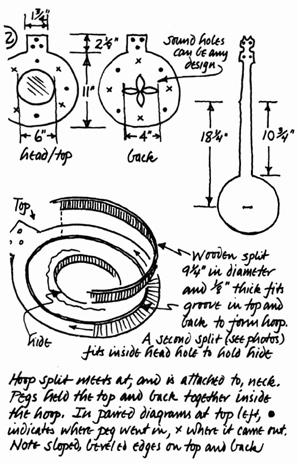

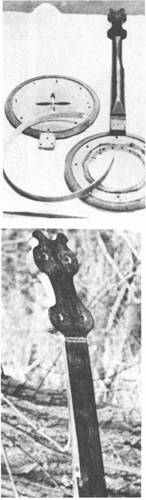

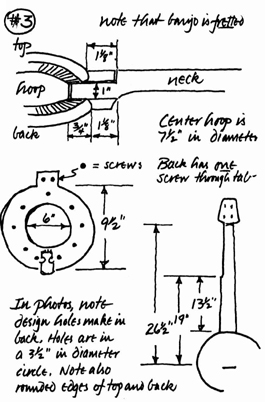

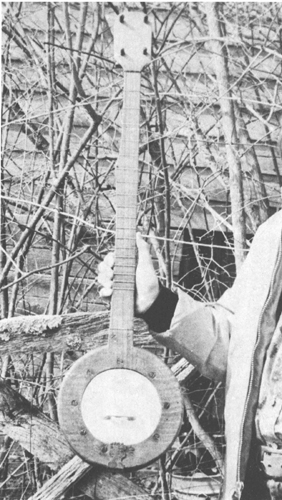

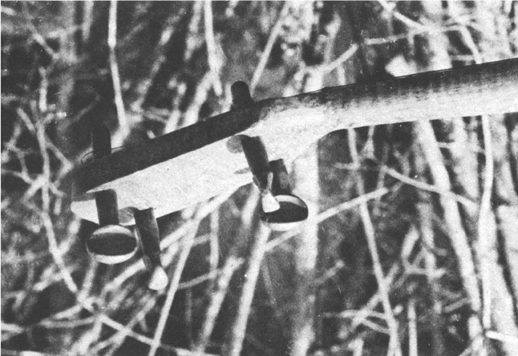

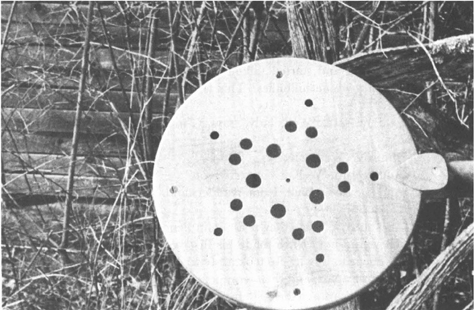

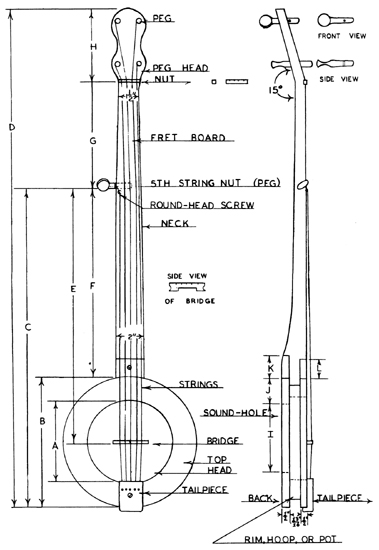

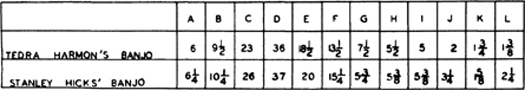

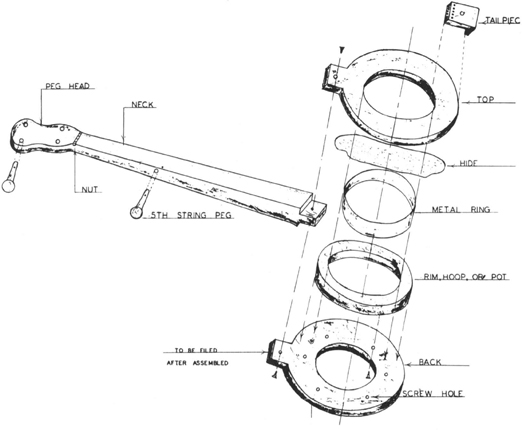

ILLUSTRATION 57 Below, ILLUSTRATION 58 shows the pieces that come with the Sturgill kit, as well as an example of the finished banjo the kit produces. There are several variations here (most incorporated from traditional instruments Dave has seen, such as those in the following illustrations) that we have not previously noted: the thin hoop, for example, that fits into corresponding grooves on the inside of the top and back. Note also that the commercial 6″ head is held into place by a wooden ring, which is in turn held in place by 5 wooden blocks nailed or screwed into the underside of the top. Note also the tailpiece—simply 3 brass brads driven into the top. The strings hook around their heads. Design and cut your own sound holes. Has fretted fingerboard. The diagrams that come with the instructions are pictured above.

ILLUSTRATION 58

ILLUSTRATION 59

ILLUSTRATION 60

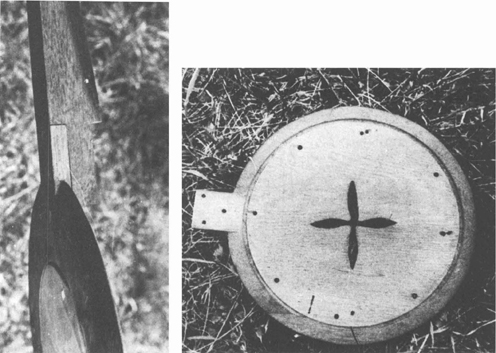

ILLUSTRATION 61 The component parts of the most elaborate Sturgill banjo laid out. They include a fully inlaid resonator.

Recently Dave went to Washington to attend a dinner celebration that Bell was sponsoring. He ran into a friend there whom he had worked with, and they began to talk about the move he had made. Asked Dave, “Who was president of this company when you and I started to work for it?”

The friend said, “I’m not sure,” and thought for a few minutes. “It was either Mr. Wilson, or …”

As Dave tells the story: “I knew who was president at that time because I’d made it a point to find out. So I reminded him which one it was. I said, ‘Now that wasn’t even thirty years ago, and you’re not even sure who the president of the company was when you started.’ I says, ‘Think about this a little bit. Twenty years from now, there won’t be anybody working for this company that will know you or I either one ever worked for it. But,’ I says, ‘a hundred years from now, they’ll be people who will know I made musical instruments.’ ”

Dave is convinced that the move away from Washington saved his life—and his spirit. “When it gets down to a question of security, the only security you can possibly have on this earth is what your Creator gives you. It doesn’t come from anywhere else. He can take it all away from you just like that, or he can give it back to you. I don’t have to worry about health insurance because I figure He’s going to look after me. So I gave up life insurance, health insurance, pension—all the rest of it—but I have absolutely no regrets. Smartest thing I ever did as far as I’m concerned, because I know now that if I’d stayed there, I’d be dead. I was getting ulcers and high blood pressure. My heart was bothering me, and several other things. And all that’s gone now. None of it’s bothering me. I’m actually in better health now, five years later, then when I left there. I certainly don’t regret leaving all that behind. And nothing would ever get me back into it, I’ll tell you. Not again.

“I’m not saying you should go completely back to Nature. That’s not the answer either. They talk about the good old days. Well, I was raised in those, and I don’t want to go back to oil lamps and outdoor toilets. That’s a little too much. But there are things that are a lot more important than how big an automobile you’ve got, or how big your bank account is. I was into it up there. An hour and a half fighting traffic every morning to get downtown. An hour and a half fighting that traffic every evening to get back. I’d be a nervous wreck every time I got on the job, and I’d be the same way when I got home. And, boy, I started asking myself every day, ‘Why? Why? What in the world am I fighting this for?’ ”

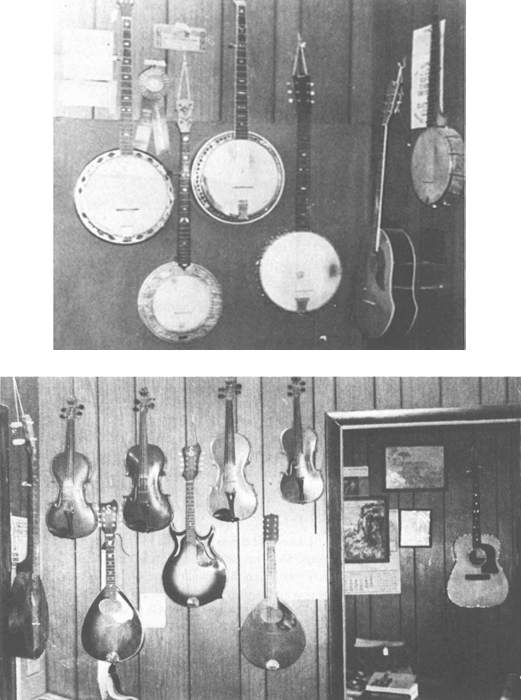

ILLUSTRATION 62 The walls of Dave’s shop are filled with instruments they have made—everything from mandolins and fiddles to guitars and banjos.

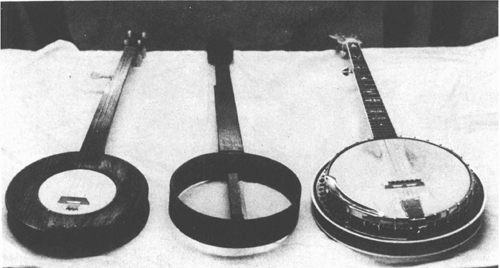

ILLUSTRATION 63 The evolution of the banjo from its simplest form to the Hicks-Harmon-Glenn variety to the most modern, complex form worthy of an Earl Scruggs.

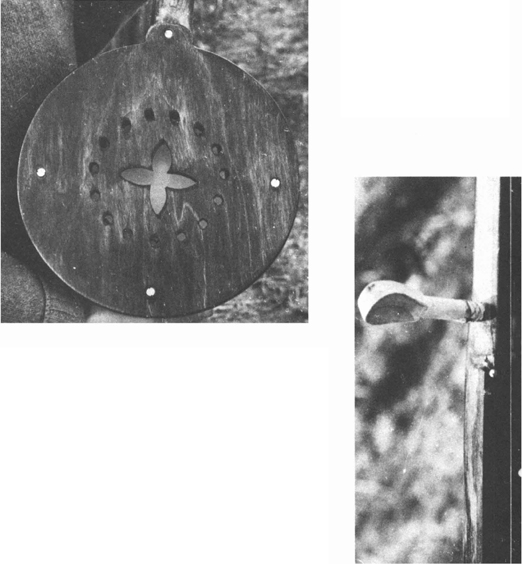

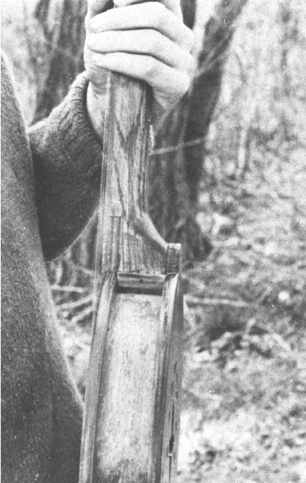

ILLUSTRATION 64-ILLUSTRATION 77 illustrate four varieties of banjos which Dave has in his collection. They are documented in the following four groups and in the “Dave Sturgill” section of the comparison chart (ILLUSTRATION 81).

ILLUSTRATION 64

ILLUSTRATION 65

ILLUSTRATION 66

ILLUSTRATION 67

ILLUSTRATION 68

ILLUSTRATION 69

ILLUSTRATION 70

ILLUSTRATION 71

ILLUSTRATION 72

ILLUSTRATION 73

ILLUSTRATION 74

Dave’s time away from the mountains, as well as the fact that the original grant for the land he now owns was made to his four-times great-grandfather and there has never been anyone but Sturgills and Indians on it, has made him passionately committed to his land and people:

“The picture that’s been drawn of these mountains down through here has been wrong—so much of it—through the years. When I was with Bell, I had several assignments up in New York City. I’d be up there sometimes for two or three weeks at a time, and those people would find out where I was from—that I came right out of the edge of the Smoky Mountains down here in the Appalachians—and they would call me ‘Hillbilly.’ They’d get a big kick out of it. And I’d say, ‘Yeah, but there’s one big difference. You can take any boy out of those hills and turn him loose in New York City and he’ll get by. But take one of you fellows down in the hills and turn you loose; you’d starve to death.’

“But the picture most of those people had of those mountaineers was pure Little Abner. Now that’s where they got it from—the comic strips. And that’s the truth today, even. Ninety per cent of the population, they think of everybody down in the mountains in terms of Little Abner. They don’t realize it’s not that way any more.

“We had some people come in here last summer when I was writing this history of my family. One woman I corresponded with was from Portland, Oregon. Her ancestors had come from here and she was very interested, and she had some information that I didn’t have. She passed that on to me, and we incorporated it into the book. But her daughter came by here last summer and called and introduced herself, and she said she wanted to come down and take a day and visit. And I told her I’d be glad to meet her, to come on down. And so she came on in here into the shop, and the first thing she said after she introduced herself was, ‘Tell me something. Where is this Appalachia I’ve been reading about and hearing about all my life? The picture I’ve always had about this country was little shacks and people sitting around on the porch.’

ILLUSTRATION 75

ILLUSTRATION 76

ILLUSTRATION 77

“And I said, ‘Well, I could take you to a few places like that, but we’d have to hunt for them. They’re pretty scarce, and they’re still a few here, but …’ ”

Dave, and most of the true mountain people, have humorous stories tucked away about outsiders that have come in looking for REAL mountain folks. We have more than a few ourselves. And the humor is often touched with a sense of anger. Dave told us his favorite:

“I’ll tell you the best one I heard of all. Up at Laurel Springs where there’s a motel, service station and so forth, a couple of years ago this big car from Pennsylvania pulled in there to get some gasoline. And the man and his wife got out—middle-aged couple—and they were straight-out tourists all the way, with the colored glasses and the shorts, the camera, the whole bit. So while the man was putting gas in the car, the woman came around and started talking to him. Says, ‘Where can we go to see some real genuine hillbillies? This is the first time we’ve ever been down in here.’

“And he says, ‘Well, lady,’ says, ‘I’m sorry,’ said, ‘you can’t see any now.’

“She said, ‘Well, why?’

“And he said, ‘Well, it’s out of season.’

“And she says, ‘Well, I don’t understand.’ Says, ‘What do you mean it’s out of season?’

“And he says, ‘Well, they’re all up in Pennsylvania teaching school!’ ”

As a young boy, Dave made his first banjo because he wanted one and was too poor to buy it. He took a plywood packing crate, set it in the creek until it came apart, and then wrapped a strip of its thin wood veneer around a five-gallon can and held it in place with rubber bands until it dried to form the hoop. Then he whittled the neck out with a pocketknife.

His interest in music came naturally. His mother could play instruments, as well as his grandfather and great-grandfather on her side. In addition, he had an uncle who liked music so well that he cleared a half-acre of land down on the river, kept it mowed, and built benches in between the willow trees. “There was a little sandy spot there where they used to land the boats. And us kids twelve, thirteen and fourteen years old, we’d get down there and play and dance and sing until three in the morning—and sometimes it would go longer than that. Dancing on the ground. He’d take wood down there and pile it up for us—always kept wood down there—and he’d build a fire and sit down there and listen to us play.”

Now Dave and his sons make mandolins, guitars, fiddles (he’s made nearly thirty-five and restored over 200 himself), dulcimers, and, of course, banjos of all types. At one end of the scale is the mountain banjo kit that they sell for $35.00. The pattern for the kit came from an old mountain banjo that was much like those that Tedra Harmon and Stanley Hicks now make except that it is fretted. The kit includes instructions as well as everything that is necessary to make one yourself from the pieces of yellow poplar (all routed, marked for holes, etc.) to the fret wire, strings, tension blocks, nails, screws and the plastic head.

At the other end of the scale is the one-of-a-kind, staggeringly beautiful custom variety that he and his sons turn out for special customers willing to pay up to $1,500.00 for one of the finest banjos money can buy. With engravings and inlay, these instruments are works of art far too complex to detail here.

ILLUSTRATION 78

ILLUSTRATION 79

ILLUSTRATION 80

Dave has done a good bit of experimentation in his time, and has whittled his choice of materials down to a few favorites. If he were to make banjos with animal hide heads instead of commercial ones, he would prefer house-cat. He has a banjo hanging on the wall that has a cat hide in it that is forty years old and still rings well. And he has also heard of catfish skin being used, and he imagines that would also be good as it wouldn’t be as subject to humidity as the other hides are.

For wood, he likes yellow poplar (his choice for the kits) because it is strong but resilient, vibrates well, and has good tone. A favorite neck of his is red oak. And for head sizes, he’s found that on the mountain-style banjo, a six-inch head with a half-inch-thick top and back rings the best.

I could tell that Dave was really happy now making instruments for a living. It shows in his work, and it shows in his face.

While we were there, Dick Finney, a man Dave grew up with, came over. Both were born on the same day, January 21, 1917, and had played together since they were young. Dick uses the second guitar Dave ever made, and Dave is building him a new one now. They played for us, Dave on the banjo and Dick on the guitar.

We played the tape we made of them all the way home.

RAY MCBRIDE

Photographs by Ray and Steve Smith.