Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound, and Revolution of the Electric Guitar - Alan di Perna, Brad Tolinski (2016)

Chapter 7. THE FAB TWELVE

In New York City’s cold, wet February of 1964, a series of interconnecting suites on the twelfth floor of the elegant Plaza Hotel was under a state of siege. Reporters, radio DJs, photographers, film crews, social climbers, hucksters, sharpies, and business opportunists of every description were working any angle they could manage in efforts to gain access. Right outside, on the southeast corner of Central Park, the icy pavements of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-eighth Street were mobbed with adolescent and preadolescent youths, mostly female, straining against police barricades that had been erected to prevent them from storming the entrances of the venerable neoclassical edifice. They too were willing to risk life and limb to get up to the twelfth floor.

In the half century since its opening in 1907, the Plaza had hosted royalty, movie stars, jet-setters, renowned authors, foreign dignitaries, and numerous other categories of VIP. But the hotel’s seasoned staff had never witnessed anything quite like this. Even some of their own number, generally discreet to a fault, were silently hoping that a call for room or maid service might bring them to the twelfth floor. A special contingent from the Burns Detective Agency was hired to stop interlopers who might attempt to get upstairs by presenting phony credentials or sneaking up a back stairway.

One person who found a welcome at the Plaza’s besieged labyrinth of suites—sailing past the screaming throngs outside and tight security within—was an unassuming businessman in his mid-fifties named Francis C. Hall. He was the head of a modest-sized company in Southern California, and he had something that was very much of interest to the Plaza’s twelfth-floor guests. Hall’s company was the maker of Rickenbacker guitars.

Surrounded by assistants and one spouse, the preeminent occupants of the twelfth floor were four young rock-and-roll musicians from working-class Liverpool, England. They were a little nonplussed to find themselves the object of so much attention, but then it was much the same back home. Already a sensation of unprecedented proportions in the U.K., the Beatles were in New York to make their debut American performance on The Ed Sullivan Show, the popular TV variety program.

For that soon-to-be-historic telecast, which would draw a record 73 million viewers, the quartet’s rhythm guitarist, John Lennon, would play a black Rickenbacker model 325 electric guitar that he’d purchased four years earlier in Hamburg, Germany. At the time of the purchase, the Beatles were just a bar band banging out rock-and-roll tunes in the seedy dives of the city’s Reeperbahn red-light district. Lennon had subsequently played his Rickenbacker guitar on most of the early Beatles records that brought the group fame. The instrument had served him well, imparting a punchy, rhythmic sense of urgency to such tracks as the group’s breakthrough American hits at the time, “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

And while the Beatles’ lead guitarist, George Harrison, would be playing his Gretsch Chet Atkins Country Gentleman electric on the Sullivan show, he too was already a confirmed Rickenbacker fan. On a late-1963 visit to his sister in the United States, he’d purchased a solid-body Rick 425 at a music shop in Illinois. Harrison’s 425 and Lennon’s 325 had both done well for the band. The Beatles were keen to meet the man whose company made those fab guitars, and to check out a few new Rickenbacker models.

—

FRANCIS CARY HALL had already enjoyed a long and distinguished career in the electric guitar industry prior to his fateful encounter with the Beatles. The son of a Southern California shop owner, he’d inherited a keen business sense. By the late 1920s, when F.C. was still in his teen years, he’d found a way to monetize his youthful interest in electronics by manufacturing batteries at home and selling them through his father’s store. This eventually grew into his own radio repair business, which by the late 1930s had evolved to become the Radio and Television Equipment Company (Radio-Tel), a major distributor of electronic parts and, eventually, Tele King television sets.

In 1946, Hall branched into another emergent technology, the electric guitar. Radio-Tel took on the distribution of the Hawaiian and lap steel guitars that Leo Fender had begun manufacturing. Also investing money in Fender’s new enterprise, Hall played a vital role in the company’s early success.

But in 1953, Fender decided to form its own in-house distribution company, effectively dispensing with Radio-Tel’s services. So Hall purchased the Electro String company from Adolph Rickenbacker and turned his attention to developing and modernizing the Rickenbacker line of electric guitars.

The company had done well under Adolph’s leadership, but it was still focused on the electric lap and pedal steel market that Electro String/Rickenbacker had launched in the thirties and had subsequently come to dominate. By 1953, however, it was clear that the times had changed. Hawaiian music and lap steels no longer enjoyed the widespread popularity they once did. And with the advent of the Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul in the early fifties, it was clear that the electric Spanish guitar was the wave of the future.

The rock-and-roll explosion at mid-decade would escalate that wave to tsunami force. So, while maintaining Electro String’s steel guitar market share, Hall set about developing a full line of Rickenbacker electric Spanish guitars, starting with the Combo 600 model in 1954. He also began courting alliances with the new breed of rock-and-roll guitarists and, for a while, had Ricky Nelson and his band playing Rickenbacker gear.

But the shift of focus from established American rock and rollers to a rising new British beat group was a quantum leap that would dramatically increase Rickenbacker’s presence in the electric guitar market. It’s important to bear in mind that the Beatles became huge in England a full year before they broke big in the States. At that time, Americans had much less awareness of what was happening in British life than they do today. Air travel was far less common; popular music, films, and television shows from the U.K. received little or no U.S. distribution. Post-World War II America just wasn’t that interested in what happened overseas.

So how did Hall even know about the Beatles prior to their American breakthrough? The answer lies in the powerful sales and distribution network he had built up over the course of the preceding decades. A Rickenbacker regional sales rep named Harold Buckner had gotten wind of the Beatles’ phenomenal rise to fame in the U.K. Also, the group’s ascendancy had brought a wave of inquiries from several British companies hoping to land a contract to distribute Rickenbacker guitars—the Beatles’ choice—in England. The contract ended up going to the Rose Morris company in England, who’d begun courting Hall quite aggressively, if cordially, even sending him newspaper clippings with photos of Lennon and Harrison playing their Rickenbacker guitars.

Lydia Catherine Hall—F.C.’s wife—began amassing a dossier on the Beatles, compiling a scrapbook that combined the clippings from Rose Morris with whatever other news items she could find on the group. (Mrs. Hall played an active role in her husband’s business, perhaps most notably designing what would become the iconic Rickenbacker headstock logo.) Based on the data his wife had collected, Hall quickly saw the band’s potential to become the biggest thing since Elvis Presley.

On January 2, 1964, Hall wrote to Buckner, saying,

Buck, this is the hottest group in the world today, as they have the two top records by popular poll in Europe; and in addition, they have the top two LP albums for the same territory. If the boys are as popular in the United States as they are now in Britain, it will not be possible to make enough guitars to supply the demands. You may think I am boasting, but this is a fact.

Buckner’s response was enthusiastic, but also cautionary. “Watch out for all those Fender promoters,” he wrote, “or they’ll have [the Beatles] playing [Fender] Jaguars and Piggybacks [that is, amps]. And don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

So Hall got to work, contacting the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, in the U.K. Epstein was no stranger to working with musical instrument companies. He’d already negotiated a deal for the Beatles to use Vox amplifiers. By late ’63/early ’64, Epstein was being besieged by business offers, including licensing deals for Beatles wigs, dolls, lunch boxes, trading cards—a virtual avalanche of merchandise. He nonetheless found time to reply to Hall’s query, which set up an exchange of transatlantic correspondence between the two men. In the end, an appointment was fixed for the afternoon of February 8, when the Beatles would be in New York to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show.

Hall enthusiastically wrote to Buckner: “I have a definite date to talk to the Beatles in New York; however please do not mention this to a soul, as I do not want our competition to know I will be in New York while they are there.”

It was a major coup for Rickenbacker. Despite George Harrison’s prominent use of Gretsch guitars, that company’s own Jimmie Webster had failed to land an audience with the Beatles in ’64. But somehow Hall had scored. Was it finesse? Timing? Sheer luck? Most likely a combination of the three.

F.C. and Catherine Hall traveled to New York in advance of the Beatles’ landing there. They took a suite at the Savoy Hotel, near the Plaza, where the Beatles were staying. Joining forces there with Harold Buckner, they set up a display of Rickenbacker instruments and amps in their suite. It was similar to the kind of hotel-room marketing displays they were creating for trade shows at the time, only for a much more select audience in this instance. Cognizant of how much was riding on the occasion, Hall had even engaged Belgian jazz guitarist and harmonica player Toots Thielemans to entertain the lads from Liverpool. Thielemans’s use of Rickenbacker guitars was what had influenced Lennon’s purchase of one of the company’s instruments back in Hamburg.

One can only imagine the level of anticipation in the room as the appointed time for the meeting drew near—let alone the consternation that must have arisen when the group failed to show up at the scheduled hour. But in due course the Savoy’s telephone operator rang the suite with a message from Epstein: the boys were running a bit late, but they would be there shortly.

The Beatles had been at a rehearsal for The Ed Sullivan Show that afternoon. Or at least three of them—Lennon, bassist Paul McCartney, and drummer Ringo Starr—had been at the rehearsal. Harrison couldn’t make it. He was confined to his bed at the Plaza with a case of the flu, hoping to recover sufficiently to perform well on the live telecast the following evening.

But once the three Beatles finished their rehearsal inside CBS-TV Studio 50 at Fifty-third Street and Broadway, they made their way over to the Savoy with Epstein and John Lennon’s wife, Cynthia, in tow. On their arrival at the Rickenbacker suite, F. C. Hall presented them with a copy of their debut U.S. album, Meet the Beatles, requesting that they autograph it. This was the first time Lennon, McCartney, or Starr had actually seen a physical copy of their first American record, and they were very pleased to do so. So Hall’s gesture turned out to be an effective icebreaker.

Catherine Hall struck up a conversation with Cynthia Lennon, one that would result in a friendly exchange of letters and cards between the two women over the ensuing years. Meanwhile, the “boys” got busy with the guitars.

Among them was a new Rickenbacker model 325 for Lennon and a Rick 4001 bass for McCartney to check out. But of all the Rickenbacker guitars on display at the Savoy that afternoon in ’64, the one that made the biggest impression was one of the company’s brand-new instruments, a semi-hollow-body electric twelve-string guitar bearing the model designation 360/12 Deluxe. Lennon and McCartney both played it and were so impressed that they invited Hall and his party back to the Plaza to show the new twelve-string guitar to Harrison.

The problem, however, was that the horde of hysterical adolescents who had surrounded the Plaza had gotten wind of the fact that three of the Beatles were now at the Savoy. So they’d run the short distance to the second hotel and laid screaming siege to it, effectively blocking the Beatles’ escape route. This kind of scenario had become an occupational hazard for the quartet and their management. Back in England, they’d evolved a whole set of strategies for evading frenzied fans, from sliding down laundry chutes to using decoy vehicles to distract overzealous well-wishers while the band escaped via another exit. But now they were in a strange city in a strange country, facing an unforeseen complication in a busy day filled with commitments and challenges.

And F. C. Hall found himself inside a scene that could have come right out of the Beatles’ first feature film, A Hard Day’s Night. Only this was real life, and there was a lot at stake for Rickenbacker’s chief—an opportunity to increase his business exponentially. So Hall went down to the hotel lobby and had a word with the Savoy’s bell captain. Hall was determined to find a way to get the Beatles, his own party, and the Rickenbacker twelve-string safely out of the Savoy and into the Plaza. He hadn’t come this far to be thwarted by a mob of screaming kids.

The bell captain pondered the situation for a while, then remembered the existence of a tunnel leading from the hotel’s basement to a discreet exit inside Central Park. He obligingly led the Lennons, McCartney, Starr, Epstein, the Halls, and Buckner down to a subterranean passageway. With F. C. Hall in possession of the 360/12 guitar, they traversed the tunnel’s length, emerged in Central Park, and enjoyed a brief stroll over to the Plaza, which they entered unharassed, making their way up to the twelfth floor.

Sitting in bed in his room, Harrison was on the telephone doing a radio interview when Hall brought in the guitar. He played it for a while and even sang a little. The interviewer asked him if he liked the instrument, and he said, “Yes, it’s a Rickenbacker.”

It was one of those mystical meetings of player and instrument that would shape the course of popular music for decades to come. The plangent jangle of Harrison’s Rickenbacker 360/12 on Beatles classics such as “I Should Have Known Better,” “I Call Your Name,” “You Can’t Do That,” and “Ticket to Ride” has become one of the great sonic signatures of mid-sixties pop music. In the process, the Rickenbacker 360/12 has been taken up by many hugely influential guitarists over the years, from Jim (Roger) McGuinn of the Byrds and Pete Townshend of the Who, to R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, U2’s the Edge, and many others.

—

VOLUMES HAVE BEEN written attempting to explain the phenomenon known as Beatlemania. Certainly no prior British musical act had enjoyed anything approaching the Beatles’ popularity in America, or indeed in the entire world. The Liverpudlian quartet were just four out of thousands of young Britons who had embraced skiffle music during the mid-1950s. Based on American folk music, skiffle favored amateur musicianship and a low-budget aesthetic that suited Britain’s struggling post-World War II economy. All you needed for instruments was an inexpensive acoustic guitar, a serrated metal washboard for percussion, and a homemade bass fashioned from a broomstick anchored onto a metal washtub.

Like many of their generation, Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr had progressed from skiffle to the brand-new rock-and-roll sounds emerging from American artists such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly, and Carl Perkins, not to mention country music and Motown. Living in the port city of Liverpool, the incipient Beatles had access to more obscure records from the United States. American sailors would bring these discs with them when they landed in the city. This, for instance, is how Lennon got his fondness for the little-known R&B artists Larry Williams and Roy Lee Johnson, whose songs would be covered by the Beatles in their early career.

The Beatles had a few distinct advantages over other aspiring rock-and-roll groups of the day. Perhaps most important, they had a formidable songwriting team in Lennon and McCartney. At the time, it was still fairly unusual for recording artists in most genres to write their own material. Even major rock-and-roll artists, such as Elvis Presley, followed the time-honored music industry practice of recording material crafted by professional songwriters. Lennon and McCartney, however, had written the Beatles’ first single, “Love Me Do,” and it had become a hit. They next convinced EMI staff producer George Martin to go with another of their own compositions, “Please Please Me,” as the Beatles’ second single, rather than cutting the song Martin had selected, “How Do You Do It” by British tunesmith Mitch Murray. The latter song would indeed become a substantial hit for Gerry and the Pacemakers. But “Please Please Me” set the world on fire.

Second, of course, the Beatles were a damn good band. Their years in Hamburg had taught them to rock hard, play tight, and sing glorious three-part harmonies. Beyond just writing their own tunes, they represented a new kind of entity in rock and roll—a self-contained guitar and vocal band that had no distinct front person. The four of them came off as a collective phenomenon.

At the time, it was still very common for session musicians to play some or all of the instruments on recordings—even those by groups containing their own guitarists, drummers, and other instrumentalists. This was true of such groups as the Beach Boys and the Byrds, both of whom would score major hits that had instrumental tracks played by a group of L.A. session aces known as “the Wrecking Crew.” The argument was that professional session musicians were more accomplished and disciplined. So they could nail a track more quickly than a young band that had just come up from the bars and clubs, thus saving hours of costly studio time. Session musicians could read music, and they belonged to musicians’ unions, which was an important consideration in some territories.

But the Beatles were at the vanguard of new groups that shattered that whole system. It’s true that George Martin had replaced Ringo with session drummer Andy White on “Love Me Do.” But he soon came to realize that the collective energy the quartet generated on its own was far more valuable than a flawless or hassle-free performance.

And it was arguably the electric guitar itself that helped make this possible. Still a relatively new instrument at the time, it didn’t carry the burden of tradition—the intimidating repertoire and legacy of virtuosity that belonged to instruments such as the violin, piano, or even saxophone. Rock guitarists were in the process of inventing their own tradition, forging their own vocabulary. As the players crafted their own guitar parts, an ability to read traditional music notation was of little or no value, and could even be a detriment to a player’s authenticity. And authenticity would become a huge issue in the mid-sixties. The Beatles’ recordings possessed a youthful exuberance that affected their young audience far more profoundly than the work of more accomplished session players “slumming” on a rock-and-roll date.

It was the start of an important paradigm shift in rock music. Rather than centering on the singing voice and visual image of one charismatic individual, a musical act’s artistic identity began to be based on a distinctive songwriting voice that could be manifested by a group or an individual. Moreover, fans began to appreciate the unique playing style of each instrumentalist—how Ringo’s approach differed from that of, say, the Rolling Stones’ Charlie Watts, or the ways in which George Harrison sounded different from the Stones’ Keith Richards. It was no longer enough just to sing well and look good. In the Beatles era and beyond, audiences began to favor artists who wrote their own material, played their own guitars, and had something to say for themselves, both in song and in interviews. It was the start of rock music’s elevation from facile teenage entertainment to a valid art form—for many, the most important art form of the twentieth century.

As a result, the instruments played by this new breed of rock-and-roll artist would become a matter of supreme importance, even to the non-musicians among their fans. No longer a mere stage prop—which was essentially what it had been for Elvis—the guitar, particularly in its electric form, became charged with the mythic significance of Orpheus’s lyre—an instrument imbued with a quasi-magical power to enthrall, entrance, and incite hysteria.

Of course, no one could have foreseen all this when the Beatles first hit America in ’64—not even electric guitar manufacturers. Still, the Beatles’ arrival and Sullivan debut conveyed a powerful sense that something completely new had landed on U.S. shores.

So the 73 million Americans who tuned into The Ed Sullivan Show on the evening of February 9 had a lot to digest—a kind of perceptual gestalt—when the Beatles took the stage. For some at the time, it seemed almost an overload of aural and visual stimuli. The quartet performed on a specially designed, modernist stage set, with geometric shapes veering inward in an exaggerated vanishing-point perspective, reframing the Beatles within the rectangular frame of viewers’ television sets as if to say, “This is where it’s at.”

Along with wide-angle shots of the entire group, the camera came in for close-ups of each band member, giving more or less equal play to each Beatle. One round of individual shots offered subtitles with each band member’s first name. Lennon’s included the caveat, Sorry girls, he’s married. For many viewers it was the first step toward discerning separate identities and personalities amid the collective phenomenon of four musicians in matching suits playing what seemed a radical new style of rock-and-roll music.

For nascent Beatlemaniacs, every detail seemed charged with significance. The group’s hairstyles, devised by German artist Astrid Kirchherr, seemed shockingly in excess of standard male hair length at the time. In fact, much of the early American media coverage of the Beatles focused more on their hair than on their music. But while an older generation made bad-barber jokes, young viewers paid almost fetishistic attention to the Fab Four’s hairstyles, their Cuban-heeled boots from London’s Anello & Davide, and their stylish, slim-cut suits by London tailor Dougie Millings. Soon kids everywhere would be desperately scouring their hometown shops for anything remotely resembling these bold new fashions. Boys who could get away with it started growing their hair out and combing it down in the front, in emulation of Beatles hairstyles. Girls sought out clothes inspired by British couturieres such as Mary Quant—miniskirts and go-go boots. Fashion and music joined forces to create a dynamic new era in youth culture.

The Beatles’ guitars commanded a huge amount of attention as well. They not only looked incredible, but were the source of this exciting new sound blasting from the minuscule speakers of several million home television sets. With its compact, violin-shaped body, Paul McCartney’s left-handed, German-made Hofner 5000/1 bass guitar was the most traditional-looking stringed instrument on the stage that night (indeed, the Hofner company dates back to 1887). As such, it seemed to complement McCartney’s persona as the nicest, homiest, most sensible Beatle—the one you’d least mind your daughter going out with. The Hofner 5000/1 became so closely associated with him that it would henceforth be known as “the Beatle bass,” no matter who else played one. And the way McCartney wielded the instrument seemed to viewers an extension of his crowd-pleasing manner. He brought the headstock up close to his face and wiggled it each time the group went into one of its “Oooohhh” vocal harmonies, eliciting a collective, cathartic, and deafening wave of screams from the audience. On these cues, the television camera would cut to audience reaction shots. It was almost as if the bass’s headstock were wired to the theater seats, transmitting a kind of electric current to fans each time McCartney wiggled it.

George Harrison’s dark brown Gretsch Country Gentleman guitar seemed a trifle too large for him, enhancing his boyish charm as he picked and fretted the instrument with a look of stern concentration. With its bewildering array of gleaming knobs and switches, it seemed a very grown-up guitar. Harrison had chosen the Gretsch in emulation of the big archtop guitars played by his rock-and-roll elders and heroes—Carl Perkins, Eddie Cochran, and Duane Eddy, not to mention the seminal country picker Chet Atkins. He’d purchased it four months earlier at the Sound City music shop in London—his third Gretsch guitar, with several more to follow during his tenure with the Beatles.

But John Lennon’s Rickenbacker 325, with its angular contours, was by far the most unconventional and modern-looking guitar played in the Sullivan telecast. Its slender black body blended with Lennon’s black jacket in such a way that it seemed to disappear from view at certain camera angles—the instrument merging with the performer’s body—leaving the impression that the instrument’s body consisted solely of its semicircular pickguard. The guitar seemed to form part of Lennon’s defiant, bowlegged stance. And while few viewers would have been able to pick out individual guitar lines, the joyous, clangorous wall of sound generated by these instruments telegraphed an incredible sense of exuberance and liberation for a generation of American baby boomers coming of age. Their peers all around the world felt very much the same.

—

F.C. AND CATHERINE HALL were present as the Beatles’ guests at the historic Sullivan telecast. A portion of F.C.’s head is even visible in some of the footage from the performance. It is not known what the couple, then in their mid-fifties, made of the event, though their son John—the current head of Rickenbacker—got the impression that they weren’t unduly impressed with the music. This culture-defining moment did, however, represent the realization of the dream F.C. had set in motion eleven years earlier, in 1953, upon purchasing the company from Adolph, when he’d embarked on the task of modernizing Rickenbacker.

One of Hall’s first moves at that time had been to hire the German-born guitar designer Roger Rossmeisl. It was Rossmeisl who would go on to design the sharp-looking guitars that helped rocket Lennon and Harrison to fame.

A stylish, handsome man of twenty-seven when he joined the Rickenbacker staff, Roger Raimond Rossmeisl was the son of German jazz guitarist turned luthier Wenzel Rossmeisl and Elizabeth Rossmeisl (née Przbylla), a singer who performed under the stage name “Lollo.” Wenzel gave his son some instruction in guitar building, but Roger also attended the prestigious Mittenwald school of instrument making in Germany. He eventually went to work for his father, who had launched a company producing archtop jazz guitars. Wenzel had named the brand after his son—Roger Guitars.

The company managed to survive the extremely difficult World War II years in Germany. In 1946, Roger spearheaded a move into electric archtops. But the company suffered a major setback in 1951, when Wenzel was jailed for a currency violation of Germany’s foreign exchange laws. Roger took over the business, but he apparently lacked his father’s management skills. Also, the younger Rossmeisl’s fondness for luxury and high living helped bring the company to financial ruin.

To escape his creditors, Roger decided to immigrate to the United States. He wrote to Gibson’s Ted McCarty, who paid Rossmeisl’s fare from Germany and gave him a job at the Gibson factory in Kalamazoo, Michigan. This, however, did not last very long. Rossmeisl clashed with McCarty, who did not care for the young man’s ideas for improving on their classic designs. And at this point, not long after World War II, Rossmeisl had apparently fallen afoul of anti-German sentiment at the factory, particularly among workers of Dutch descent.

So Rossmeisl used the pretext of vacation leave from Gibson to travel out west and land a gig playing guitar on a ship bound for Hawaii. Following the vessel’s return voyage to L.A., he took a job at Rickenbacker.

Rossmeisl’s design work for Rickenbacker combined the Old World classicism of Mittenwald violin-making; the jazzy flair of his namesake, Roger Guitars archtops; and a sleek, industrial, modernist aesthetic that seemed attuned to the sensibility of Germany’s Bauhaus school of design. He tended to simplify and sharpen the angles of more traditional guitar designs. Some of the rounded contours became more pointed. The traditional violin-style f-holes became elongated slashes. Every surface and detail of the electric guitar, as reimagined by Roger Rossmeisl, became streamlined in a new, harmonious whole.

“Roger certainly had a sense of style and design,” said John Hall, son of F. C. Hall and Rickenbacker’s current owner, who knew Rossmeisl personally. “The guy was a real sharp dresser. He always had impeccable clothing—the latest styles. You can see that in photos of him. He also had a Sunbeam Alpine sports car. He had a real sporty kind of outlook on things.”

While Rossmeisl’s life would spiral tragically downward into alcoholism and an early death, his years at Rickenbacker represented a high point for him both professionally and personally. He and his wife would visit the Hall family at Christmas bearing lavish gifts. The presents were “very creative and unusual,” the younger Hall recalled. In the late fifties, Rossmeisl designed the Rickenbacker Capri series of guitars, which would morph into the 300 series, which included both John Lennon’s 325 and George Harrison’s 360/12.

“He became the father of our modern Rickenbacker design,” Hall said.

The twelve-string guitar had been around for ages in its acoustic form, finding a home in folk music and blues through the work of performers such as Leadbelly, Blind Willie McTell, and Pete Seeger. Where a standard guitar has six strings, a twelve-string has six pairs of strings, known as “courses.” The two strings in each course are spaced closely together, so that the player’s fretting finger can press both down simultaneously. The twelve-string guitar produces a bigger, more sonorous tonality than its six-string counterpart, a sound that Pete Seeger once described as “the clanging of bells.”

Prior to Rickenbacker’s introduction of the 360/12 in 1964, both Gibson and a tiny company called Stratosphere had attempted to market twelve-string electrics. But neither had met with any real success. Had it not been for the Beatles, the Rickenbacker twelve-string electric design might have fallen by the wayside, too—which would have been a shame, given both the visual and tonal beauty of the instrument.

In electrifying the twelve-string guitar, Rickenbacker introduced a few innovations. The way the courses were strung was slightly different, resulting in a new kind of tonality. Second, an ingenious new headstock arrangement had tuning keys for the principal strings facing outward, in the conventional manner, while keys for the doubled strings faced backward. It’s a subtle difference to the non-player, but as Harrison is alleged to have said of the Rickenbacker’s revised design, “Even when you’re drunk you can still know what string you’re tuning.”

The Rickenbacker 360/12 that Hall brought to Harrison at the Plaza was the second ever manufactured. (The first went to Las Vegas entertainer Suzi Arden, a personal friend of Hall’s.) Harrison ended up keeping the guitar for his own, and would later acquire a second 360/12, putting both to excellent use. Lennon would commission Rickenbacker to make him an electric twelve-string version of the small-bodied model 325 that he favored. Hall’s hunch that the electric twelve-string’s innovative design and distinctive sound would appeal to the guitarists in a groundbreaking musical group paid off in a big way. Design work on the 360/12 had begun in 1963, the same year that Beatlemania took hold in England, and in that regard the instrument and the group that made it famous were completely contemporaneous.

The Beatles’ prominent use of both Rickenbacker and Gretsch guitars in the early years of their career brought about a tremendous increase in sales for both companies. In the pre-Fab Four 1961-63 period, Gretsch produced an average of 5,000 guitars per year. By 1965, at the height of Beatlemania, that number had jumped to 13,000 units per year. Harrison’s preferred Country Gentleman 6122 was one of Gretsch’s biggest sellers, with production jumping from an annual average of 200 in 1962 to 1,400 by 1965. At Rickenbacker, the story was much the same. The company had to move into a larger building to step up production, upgrading manufacturing equipment and employee compensation.

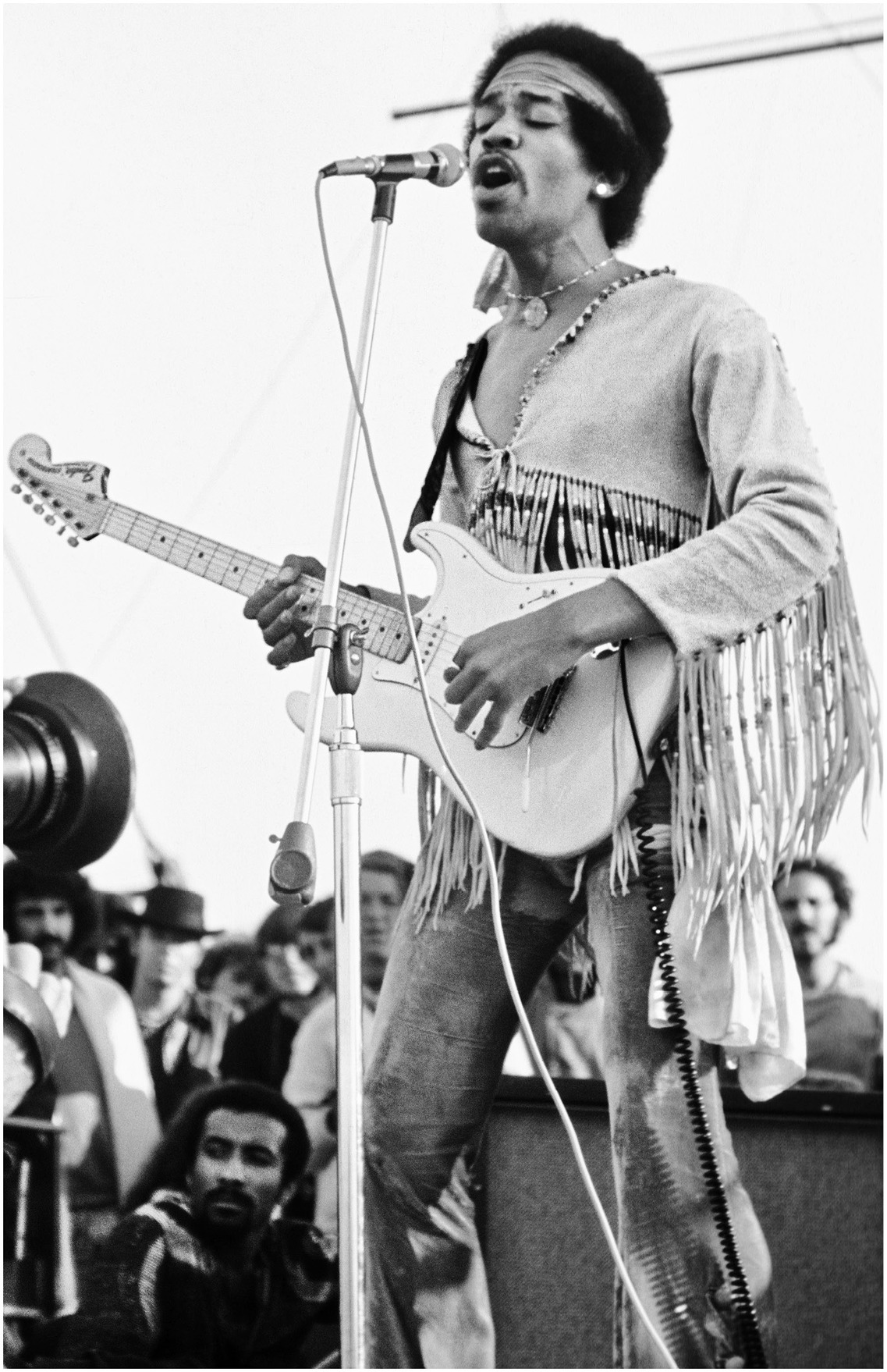

While Harrison generally deployed the Rickenbacker electric twelve-string for chiming, melodic guitar parts, he tended to use his Gretsches for grittier leads, and also passages that showed off the strong country influence in his playing, such as the concise, eloquently terse solo in “Can’t Buy Me Love.” Like many of their British Invasion contemporaries—perhaps most notably Keith Richards and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones—Harrison and Lennon weren’t locked into strict lead guitar/rhythm guitar roles. There was a greater freedom of interplay between guitarists in early- to mid-sixties rock music, before lead guitar became the rarefied domain of virtuoso players such as Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton.

—

ALONG WITH HAVING SPORTS CARS, mansions, and posh girlfriends, rock guitarists who land on top of the charts will most certainly spend their newly acquired cash on some new axes. The Beatles were no exception, amassing an array of Gibsons and Epiphones early on. But it’s not so much the guitars themselves as what the Beatles did with them. They were brilliant innovators in the nascent field of rock guitar aesthetics, crafting both highly original chord progressions and a fascinating array of new guitar textures never heard before. Where jazz guitarists tend to innovate through harmonically clever and virtuosically dexterous note choices, remaining relatively indifferent to tone, rock guitarists tend to innovate sonically, often going to great lengths to coax arresting, startling, or mesmerizing sounds from their guitars, amps, and other equipment. It’s a holistic approach that embraces the entire signal path, from strings to speakers. And, in a rock context, the Beatles are the towering figures at the dawn of this tradition—the gateway, if you will, to Hendrix, Townshend, Beck, and other rock titans.

The Beatles’ 1964 single “I Feel Fine” opens with the first-ever deliberate and imaginative deployment of guitar feedback on a rock record. John Lennon and his bandmates had come upon the sound accidentally and decided to put it to creative use. They were fortunate in having a producer, George Martin, who was not only willing to adopt their unconventional creative ideas, but also able to provide the technical know-how necessary to implement them.

The Beatles also pioneered the use of “backwards” guitar for the solo in their 1966 song “I’m Only Sleeping”—achieved by recording a guitar part and then flipping the tape reels around on playback to create a surreal, dreamlike sound. This would become a hallmark of the psychedelic period, just getting under way at the time. No stranger to innovation himself, Paul McCartney was arguably the first musician to run a bass guitar signal through a fuzz pedal, which he did on the Beatles’ 1965 recording “Think for Yourself.” The same device was responsible for the guitar lead in the Stones’ “Satisfaction,” released that same year.

—

THE SUCCESS OF the Beatles in 1964 touched off a full-scale British Invasion of what were then called “beat groups” from the U.K. The Dave Clark Five, the Animals, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Yardbirds, Herman’s Hermits, the Hollies, the Zombies, the Searchers, the Moody Blues, Gerry & the Pacemakers, Manfred Mann, Freddie & the Dreamers, Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas, and numerous other electric guitar-driven English rock-and-roll groups enjoyed massive worldwide hits in the mid-sixties. In the United States, the network television shows Shindig! and Hullabaloo, along with variety programs such as Ed Sullivan’s and a handful of local rock-and-roll shows in major U.S. markets, afforded fans precious opportunities to see the new British groups in action.

In Great Britain, too, the Beatles and their contemporaries represented the first major new movement in rock-and-roll music and culture since the music’s original breakthrough in the mid-fifties. And this time, it was a homegrown phenomenon. Young Britons eagerly tuned into ITV’s program Ready Steady Go! each week to watch England’s newest hit-makers perform their latest songs. But the new sounds created a great, and often hostile, divide in British youth culture. The fashion-forward Mods embraced the new British-made rock—particularly that of the Who, the Kinks, and Small Faces—along with the contemporary sounds of American Motown and Jamaican ska, known as “blue beat” at the time. On the other hand, there were the Rockers, who clung to the old sounds of artists such as Elvis and Gene Vincent and the 1950s “greaser” style, with slicked-back hair and leather motorcycle jackets. Asked by an interviewer in a scene from A Hard Day’s Night if he was a Mod or a Rocker, Ringo Starr replied, “I’m a mocker.”

The music of these new bands from Britain was all heavily influenced by American rock and roll, blues, and R&B. And they were playing it, for the most part, on Gretsches, Rickenbackers, Gibsons, Epiphones, and other American guitars. So why, then, did it sound so distinctly English? There are several factors, among them the cultural differences between the young British musicians and the predominantly African American artists they were emulating. But it would be difficult, in assessing the beat-group sounds coming out of the U.K. in the mid-sixties, to overestimate the role played by British-made Vox guitar amps. The sound of the British Invasion is very much the sound of Vox.

The amplifiers grew out of a partnership between businessman and accordion player Tom Jennings and guitarist Dick Denney, who first met during World War II while working at a munitions factory in Britain. The two men formed Jennings Musical Instruments (JMI) in 1957, and began producing amplifiers, and later other products, under the Vox brand name. JMI brought the first Vox amplifier, the AC15, to market in early 1958. Designed by Denney, the 15-watt guitar amp was markedly different from the amplifiers that Leo Fender and other American innovators had been designing and marketing. Vox amps employed different tubes and a different configuration of components to create a bright, highly dynamic tonality that would become closely identified with the “jangle” of the British Invasion sound. In the vivid language of noted amp expert, guitarist, Marshall amp design consultant, and former vice president of marketing for Fender Ritchie Fliegler, a Vox amp from this period is “on 10 and wailing the whole time it’s on.”

The 30-watt Vox AC30 was introduced in 1959, and remains one of the standards in rock guitar, still very much in use today. But the thing that really crystallized Vox’s wow factor was the advent of the company’s Top Boost circuit—essentially an extra treble control—for the AC15 and AC30. Top Boost is what’s largely responsible for the brilliant timbre of something like the guitar intro to the Beatles’ “Eight Days a Week.”

Shortly after launching JMI and Vox amps, Jennings and Denney opened a retail shop at 100 Charing Cross Road in London, with a nearby manufacturing facility in Dartford, Kent. Their goal from the start was to get into the burgeoning market for electric guitar gear that had been initiated by the advent of rock and roll in the mid-fifties. They scored a major triumph in late 1959 when the Vox AC30 became the amp of choice for the Shadows, Britain’s top rock-and-roll band at the time, led by bespectacled guitarist Hank Marvin. The Shadows had a dual-pronged career. On the one hand, they were the backing band for the popular U.K. rock-and-roll singer Cliff Richard, sometimes described as “the English Elvis Presley.” But the Shadows also released a very successful string of guitar instrumental tracks on their own. When they deployed their Vox AC30s on their 1960 instrumental hit “Apache,” it did not go unnoticed.

Most of the young, soon-to-be British Invaders were huge Shadows fans. “Before Cliff and the Shadows, there had been nothing worth listening to in British music,” John Lennon once said. Lennon and Harrison had named an early instrumental of theirs “Cry for a Shadow” in honor of the group, emulating the Shadows’ sound and style.

So it was no mere whim that brought Brian Epstein into JMI’s Charing Cross Road shop in July of 1962. He offered store manager Reg Clarke a deal: If Clarke would supply the Beatles with free Vox amps, the group would agree to use Vox amplification exclusively and also lend their image, likeness, and words of endorsement to Vox ads and other promotional endeavors—a true PR and marketing bonanza. Of course, the Beatles were still a virtually unknown commodity in the summer of ’62. They’d just barely managed to secure their recording contract with EMI, having been turned down previously by Decca. They had yet to score any hits. But Epstein nonetheless assured Clarke that his boys were going to be “very big indeed.”

Clarke phoned his boss, Tom Jennings, to ask what he should do. The store manager later said he would never forget Jennings’s response to Epstein and his offer: “What does he think we are, a fucking philanthropic society?”

Clarke nonetheless made a pact with Epstein, thereby saving himself and Jennings the ignominy of going down in history—along with Decca Records’ Dick Rowe—as men who had been foolish enough to turn down the Beatles. And so John Lennon and George Harrison each got a tan Top Boost AC30. These were promptly put to use onstage and, on September 4, 1962, at Abbey Road Studios in London, where the Beatles recorded “Love Me Do.” Paul McCartney got his first Vox bass amp in early 1963. JMI would continue to supply the Beatles with Vox gear throughout their career, crafting louder and louder amps to compete with the decibel levels generated by audiences filled with screaming young Beatlemaniacs.

Like everything else surrounding the Beatles, Vox amps looked as fabulous as they sounded. While Dick Denney brought engineering talent to the equation, it was Tom Jennings who had a flair for stylish visual design. The amps’ diamond-pattern grille cloths, bold VOX logos, and space-age chrome stands all became vital British Invasion signifiers.

Tom Jennings had obviously changed his tune about philanthropy. By the mid-sixties, Vox product catalogs were proudly displaying a photographic who’s who of British Invaders, including the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Animals, the Dave Clark Five, Manfred Mann, the Hollies, the Searchers, and many others. Also seen with their stacks of groovy Vox gear were several of the British Invaders’ key American counterparts, such as the Standells, the Sir Douglas Quintet, and, fittingly enough, Paul Revere & the Raiders.

—

OF ALL THESE new rock-and-roll groups, it was of course the Rolling Stones who had claimed a place right alongside the Beatles at the top of the heap. The Stones’ manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, shrewdly saw the efficacy of marketing the Stones as a kind of anti-Beatles. To young rock-and-roll audiences at the time, the Rolling Stones offered a kind of primal, dark, Dionysiac alternative to the Beatles’ more sunny, well-groomed Apollonian appeal.

While a lot of this was just media hype, there was nonetheless an essential difference between the Beatles and Stones. It was—and remains—immediately discernible in their music. Unlike the Beatles, the Stones started out as blues and R&B purists. While they’d been profoundly affected by the birth of rock and roll in the mid-fifties, they’d focused their attention on the music’s African American antecedents in a way that the Beatles hadn’t. A big part of it was being from London, where a small but enthusiastic blues/R&B scene had grown up.

It had originated in an enthusiasm for “trad,” or traditional African American jazz—what we might now call Dixieland or New Orleans jazz—that had taken hold of England in the fifties. Trad was part of a larger appreciation in Britain at the time for the many genres that make up what is now called Americana, or American roots music. A key figure on the trad scene was trombone player and bandleader Chris Barber. He’d touched off the skiffle craze by fostering the career of guitarist, banjo player, and vocalist Lonnie Donegan.

And—perhaps more significant, given the direction guitar-based rock music would take over the next three decades—Barber also brought African American blues into the U.K. by promoting concert appearances and tours by seminal bluesmen such as Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters, and the harmonica/guitar duet of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. In the audience for many of these early blues dates, assiduously taking in every detail, were future British rock stars such as Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and, of course, the Rolling Stones.

One of the bluesiest elements in many of the early Stones recordings is electric slide guitar, often played by one of the group’s founding members, Brian Jones. A heavy hitter on the London R&B scene—arguably heavier, at that time, than the Stones’ cofounders, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards—Jones is often credited as the first musician in England to play slide guitar. Performing at early London venues such as the Marquee and the Ealing Jazz Club, he had even billed himself as Elmo Lewis—a tribute to American bluesman and slide guitar pioneer Elmore James, combined with the first part of the young guitarist’s given name, Lewis Brian Hopkin Jones.

It was also Jones who gave the Rolling Stones their name, appropriating the song title “Rollin’ Stone” from pioneering bluesman Muddy Waters. Even more so than the music of Elmore James, Waters’s music would have a tremendous influence on the Stones. Sharing a squalid London flat with Jagger and another friend, Jones and Richards would spend hours listening to records.

“When we started playing together,” Richards said, “we were listening to Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters—the two-guitar thing, the weaving. We did it so much, which is the way you have to do it. So we both knew both guitar parts. So then you get to the point where you get it really flash and you suddenly switch—the other one picks up the rhythm and the other one picks up the lead part.”

“I hope they don’t think we’re a rock and roll outfit,” Mick Jagger told London music rag Jazz News in ’62. This quote was often cited ironically in later years, when the Stones became known as “The World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band.” But it was an important distinction to make in London of 1962.

“British R&B bands, we called them at the time,” recollected Giorgio Gomelsky, who managed both the Stones and the Yardbirds early on, and ran London’s “most blueswailing” nightclub, the Crawdaddy. “Because rock and roll was not that. It was considered white, surfing, teenybopper music—the corporate rock of that time. All these people like Fabian, these sort of pseudo Elvis Presleys.”

Even in ’62, though, there was a note of hypocrisy—or perhaps just plain hype—in Jagger’s claim that his band was not “a rock and roll outfit.” The early Rolling Stones would cover Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly songs, just as the Beatles would do. But aligning oneself with more traditional African American styles was a badge of authenticity on the tiny London scene that fostered the early Stones. Two early Stones members, Geoff Bradford and Brian Knight, had actually quit the band because they took exception to Richards’s fondness for Chuck Berry.

“The very little budding blues scene in England—all four hundred of us—were split into two camps,” according to Gomelsky. “ ‘That version of Chuck Berry is not blues.’ ‘Yeah, but that version of so-and-so is not rhythm and blues.’ Blues Unlimited, one of the big fanzines at the time, were distributing pamphlets. All these disputes were going on and at the same time bands were playing and the scene came about. And [the disputes] didn’t make any difference afterward.”

In this context, it’s significant that the Rolling Stones’ first single was a Chuck Berry cover, “Come On,” released in June of 1963. It was rock and roll enough to launch the Stones out of the insular London R&B scene and into the same wide world of hysterical teenage fan adulation that the Beatles had both generated and attracted.

“We were a blues band,” Richards commented years later, “[but] we made just one little pop record and it became a hit. Or semi-pop. And suddenly chicks screamed at you and you’re not playing for anybody anymore. You’re just wondering how the hell you’re going to get off this stage and safely get out of this town before you get ripped to shreds…Weird, manic. And you’re thinking, ‘But I’m a blues player!’ ”

“The Stones weren’t really a girls’ band, man,” Gomelsky reflected. “None of the R&B bands were. Ninety percent males used to come to the shows, among them the Pete Townshends, Eric Claptons, and Jimmy Pages…all those people. The Beatles were more a girls’ band. But, in the end, you can’t resist the sexual economics.”

Which is to say that the Stones were a gateway to the blues for many young musicians and listeners, both American and English. By covering so many blues classics by artists such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, the Rolling Stones aroused a powerful curiosity about the originals in the minds of adventurous young guitarists seeking new sounds and inspirations. With a dearth of written information about these artists available at the time, Stones fans traced down the names in the songwriting credits on the group’s albums and singles. (Who is McKinley Morganfield? Ah, it’s this guy they call Muddy Waters. Who the hell is Chester Arthur Burnett? Oh, that’s Howlin’ Wolf.)

It was an act of cultural appropriation, certainly. But the Rolling Stones in particular were eager to share the limelight with their blues heroes, exposing them to an enthusiastic new audience that, in years to come, would provide African American bluesmen with a significant new source of income in record sales and song royalties. One of the Stones’ greatest coups was to arrange for Howlin’ Wolf to perform on America’s premier pop-music television program, Shindig!, in 1965. The sight of a large, black man in his mid-fifties shakin’ his thang before an audience of somewhat bemused white American teenagers and a spellbound Brian Jones remains one of the strangest and most evocative video artifacts of the mid-sixties.

Much like the bluesmen of old, Keith Richards and Brian Jones started out playing fairly modest electric guitars made by Harmony, the American company that specialized in affordable instruments, selling many through retail outlets such as Sears in the States. Jones played a Stratotone and Richards a Meteor. But they gradually worked their way up to better guitars as the Stones’ popularity grew, Jones gravitating toward a Gretsch Anniversary model and Richards an Epiphone Casino, both hollow-body instruments. High-quality electric guitars were still hard to come by in the U.K., as indicated by the fact that Lennon and Harrison had bought their Rickenbacker electrics in Germany (where distribution was a bit more reliable) and the United States, respectively.

Fame brought the Stones their own endorsement deal with Vox. An early Vox promo shot captures the brief period when the Rolling Stones wore matching band outfits, featuring leather vests. Many of the early Stones recordings, not to mention live shows, were done on Vox amps, principally AC30s. Jones also became closely associated with the teardrop-shaped Vox Mark III electric guitar. The idea for the instrument came from Vox chief Tom Jennings, as part of his ongoing quest to position Vox as makers of not just amps but the absolutely coolest-looking instruments on the scene. To that end, Jennings instructed Vox chief design engineer Mick Bennett to craft an electric guitar with a body shape resembling that of a lute. The prototype was given to Brian Jones.

It was an obvious choice. The visual reference to the Renaissance lute suited Jones’s romantic public image. His fluffy mane of “Prince Valiant” blond hair had always set him apart, giving him an air of almost feminine vulnerability that appealed to young girls in a powerful way. Jones was always the most flamboyant dresser among the Stones, and the uniquely shaped white guitar seemed an extension of his image and persona, much in the same way that Lennon’s Rickenbacker 325 was part and parcel of his identity as a performer. Vox also made a twelve-string version of the Mark III for Jones. They created a teardrop-shaped bass guitar for the Stones’ bassist as well, marketed as the Vox Bill Wyman model. Production models of all these teardrop instruments, as well as the more angular Vox Phantom models, became highly sought-after items among up-and-coming guitarists and aspiring future rock stars during the mid-sixties.

Instrumentally, Brian Jones was the Stones’ most “outside the box” thinker. It was he, for instance, who took a metal slide to a Rickenbacker electric twelve-string to create the signature riff on the band’s 1966 hit “Mother’s Little Helper.” This was far from standard procedure. The guitar, moreover, was just one of many instrument choices for Jones. He played harmonica predominantly on a lot of the early Rolling Stones recordings. And as the group developed stylistically, he branched out into a kaleidoscopic array of instrumental colors—Indian sitar, Appalachian dulcimer, recorder (the wooden flute heard on “Ruby Tuesday”), marimba, organ, piano, saxophone, and pretty much anything else that came to hand in the recording studio. This became a key role for him as Jagger and Richards’s ascendancy as the Stones’ songwriters thrust them into a leadership position that Jones once saw as his own.

“Brian was always searching for another sound,” Richards recalled. “As a musician he was very versatile. He’d be just as happy playing marimba or bells as he would guitar. Sometimes it was, ‘Oh make up your mind what sound you’re going to have, Brian!’ ’Cause he’d keep changing guitars. He wasn’t one of those guys who said, ‘Right, here’s my axe.’ ”

Jones’s multi-instrumental tendencies, combined with his drug-fueled personal decline, would lead Richards to assume a more prominent guitar role as the sixties progressed. In August of 1964, Richards acquired what would become an iconic instrument for him—a 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard equipped with a Bigsby tailpiece that had been installed by the instrument’s previous, and original, owner, British guitarist John Bowen. It became Richards’s main guitar between ’64 and ’67, seen by many Americans for the first time when he played it on the Rolling Stones’ debut Ed Sullivan Show performance, on October 25, 1964.

“It was my first touch with a real great, classic rock and roll electric guitar,” Richards said in 1997. “And so I fell in love with [Les Pauls] for a while.”

Richards’s 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard has become the stuff of rock-and-roll legend. Stories circulated that it is the same guitar later owned by Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page. (It’s not.) In 1967, Richards sold the guitar to Mick Taylor, who within two years would become Brian Jones’s replacement in the Rolling Stones. But as the existence of the myths themselves attest, Richards’s 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard has come to be regarded with awe. It’s seen as a gateway instrument—a harbinger of the late-sixties age of the guitar hero. Shortly after Richards took up the Les Paul Standard, guitar icons such as Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and Mike Bloomfield all did the same, playing that instrument on some of their most significant recordings. So, just as the Stones turned a generation of guitarists onto the blues through their covers of songs by Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and other American bluesmen, “Keef” is seen as forging the path that made the Les Paul Standard one of the most important instruments in rock history.

—

AMONG ITS MANY other contributions to popular culture, the British Invasion era gave the world some of the greatest electric guitar hooks ever recorded. In this area as well, the Beatles and the Stones were at the head of the pack. The mid-sixties rock-and-roll market was very much based around hit singles rather than album sales. In order to stay in the game, groups had to come up with a new chart-topping track every month or so. An attention-grabbing introductory guitar riff was an essential part of the format. Guitar intros had been around since the dawn of rock and roll in the fifties in the exemplary work of guitarists such as Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins. But these intros were often just that, a perfunctory two or four bars of electric frenzy that would then give way to a vocal and never be heard again, except perhaps at the end of the song.

The art of the almighty riff hit a new height in the mid-sixties. Designed to grab and hold the listener rapt, the riff would not only introduce the tune; it also become an integral part of the song’s spine, underpinning a verse vocal melody, as in the Beatles’ “Day Tripper,” or driving home a money-shot chorus vocal, as in the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction.” Chordal arpeggios and patterns, such as those in the Animals’ “The House of the Rising Sun” or the Searchers’ “Needles and Pins,” could be equally effective. The tone of the electric guitar was in itself a signifier of excitement. Perhaps the greatest example of this is the single guitar chord that opens the Beatles’ “A Hard Day’s Night.” The timbre of Harrison’s Rickenbacker 360/12 through a Vox amp, shadowed by Lennon’s Gibson J-160E, also played through a Vox, is a musical statement in itself.

One key difference between the Stones and the Beatles is that the latter were working in the studio with a formally trained musician and record producer, George Martin, whereas the Rolling Stones’ earliest recordings were produced by their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham. Both were excellent producers in their own right, but they were very different in style and approach. Martin was somewhat older than the members of the Beatles, an avuncular figure who was very open to the group’s creative ideas but also made sure that everything went down to tape in accordance with proper EMI technical standards. Oldham was somewhat closer in age to the Stones, and had had no prior experience as a record producer when he began working with them. As a result, the artist/producer relationship was more one of lads running amok together in the studio. Also, while the Beatles almost always recorded in the familiar and controlled environment of EMI’s Abbey Road Studios in London, the Stones ventured further afield into less familiar studios on less familiar turf. They worked at the RCA facility in Hollywood, and Chess Studios in Chicago, where their heroes Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, and others had made historic blues recordings.

All of which contributed to a perception of the Rolling Stones as having a more raw sound than the Beatles. This in turn fueled the Stones’ image as a dangerous, outsider alternative to the Beatles. However cordial relations between the two groups may have been, “Stones vs. Beatles” became the dialectic that defined much of pop music in the mid-sixties. Bands tended either to be rough and ready, Stonesy, bluesy, R&B-inflected outfits—like the Kinks, the Who, the Animals, and the Yardbirds—or more Beatlesque groups with pristine vocal harmonies, in the manner of the Hollies and the Zombies. Needless to say, their guitar choices were also often based on those of the band(s) they emulated.

—

THE PROFOUND CULTURAL impact of the British Invasion did much to encourage teenagers on both sides of the Atlantic to get hold of some electric guitars and form rock-and-roll bands in the basements and garages of their parents’ homes. If anything was more exciting than growing your hair out and suiting up in groovy Mod gear, it was kitting yourself out with an electric guitar and amp, recruiting some friends, and actually trying to make music like the Beatles, the Stones, and other British Invaders.

As a result, the demand for electric guitars went through the roof. At the top of the food chain, premier American makers such as Gibson, Fender, Gretsch, and Rickenbacker all went into manufacturing overdrive. But a flood of inexpensive foreign imports from Japan, Germany, Sweden, Italy, and other countries began to flow into both the U.S. and the U.K. Teisco Del Reys, Kents, Silvertones, Ekos, and Hagstroms were among the overseas brands often sold through department stores rather than specialist music shops. American brands such as Harmony, National, Valco, Kay, and Airline also came in at bargain prices. Many were starter instruments, some better than others. Players who showed some ability and genuine interest might move on to a higher-quality guitar.

So the British Invasion was to guitar music roughly what the Gutenberg Bible and advent of printing had been to literacy. It touched off a cultural explosion. Playing music—and specifically electric guitar music—became a vernacular pursuit, the musical voice of the masses. And garage bands became the primary arena for this new musical conversation.

The garage rock groundswell that had begun with the rise of amateur surf instrumental bands a few years earlier gained dramatic momentum in the months and years after the Beatles’ early-1964 U.S. debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. By the mid-sixties, garage rock had emerged as a distinctive rock-and-roll subgenre in its own right, with regional, national, and sometimes international hits by garage outfits such as the Standells, the Shadows of Knight, Question Mark & the Mysterians, the Music Machine, Music Explosion, the Sonics, and the Knickerbockers. The sound tended to be a few shades raunchier than the Stones or the Kinks at their rawest, and the overall garage band aesthetic was a bit more low-budget than what the bigger English and American groups were doing at the time. But that was all part of the appeal. The “anyone can do it” accessibility of mid-sixties garage rock would become a major inspiration for punk rock a decade later, not to mention several garage rock revivals.

With young guitarists on both sides of the Atlantic seizing Rickenbackers, Gretsches, and other electric guitar models, the British “Invasion” had given way to an impassioned, creative, two-way dialog between British and American rock musicians. By 1965, musical ideas and influences were traveling both ways, back and forth across the Atlantic at the speed of sound. This dynamic cultural exchange would shape the course of rock music in the decades that followed. The shared basic language of this inspired détente was the broad lexicon of American roots music. But in embracing it as their own, the Beatles, the Stones, and other British groups transformed it into something new and exciting. And in bringing it all back home, the Americans took British innovations and traditions on board. The strategic alliance that made all this possible, the marriage of American guitars and British amps, proved to be one made in rock-and-roll heaven.

The 1968 Fender Stratocaster that Hendrix played at Woodstock sold for $2 million in 1998.