Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound, and Revolution of the Electric Guitar - Alan di Perna, Brad Tolinski (2016)

Chapter 3. THE WIZARD FROM WAUKESHA

In the late 1940s, the house that once stood at 1514 North Curson Avenue in West Hollywood wouldn’t have attracted much notice. In all its external details, the dwelling typified the cozy domesticity and middle-class comfort of American life in the years immediately following World War II. A trim, unassuming single-story structure, the house had a modest patch of front lawn that was adorned with palm trees and verdant Southern California foliage. A straight concrete pathway led up to four steps flanked by white columns, beyond which lay the front door.

The house was just around the corner from the stretch of Sunset Boulevard known as Sunset Strip—then, as now, a thoroughfare associated with showbiz glamour. The golden age of Hollywood filmmaking was in full swing, and the town’s movie studios were turning out box-office smashes and instant classics such as The Big Sleep, Notorious, Gilda, and Mildred Pierce. Sunset was the playground of movie moguls, mobsters, stars, and starlets who would dine and dance at the Trocadero, the Mocambo, Ciro’s, and other exotic boîtes de nuit. Strolling down Sunset, you could get a fine suit at Michael’s Exclusive Haberdashery—a front for the notorious gangster Mickey Cohen—or have an ice cream at Schwab’s drugstore soda fountain, where film star Lana Turner was said to have been discovered. Celebrities and would-be celebs resided at the Garden of Allah, Sunset Tower, Chateau Marmont, or one of the area’s tropically themed garden apartment complexes.

But L.A. has always been a place where you could turn off a busy main drag like Sunset and find yourself on a tree-lined, distinctly suburban side street, with rows of well-kept homes. The house on North Curson was just such a place, and its owner was something of a celebrity in his own right. Then in his thirties, Les Paul had established himself as one of America’s foremost guitarists through frequent radio appearances, live performances, and recordings with his own Les Paul Trio and top singers of the day, such as Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters. Audiences appreciated his homespun good humor as much as they enjoyed his supple guitar work.

In the late 1940s, Les would sometimes play host to two other men with more than a glancing interest in the guitar. They’d sit on the back patio at Les’s place, drinking beer and exchanging ideas. Unlike Les, they weren’t at all famous at the time—just humble tradesmen and fellow tinkerers from down in Orange County, south of L.A. and appreciably less fabulous than West Hollywood.

Leo Fender was a bit older than Les Paul, pushing forty at the time. Unlike Les, he was a native Californian, born and raised in Fullerton, where his parents had an orange grove. To a certain extent, Fender was the kind of guy that people would later call a nerd—a bespectacled man quietly obsessed with the mechanical and electrical workings of things, invariably equipped with a few pens and pencils protruding from the front of his shirt in a plastic pocket protector. He had recently parlayed his radio repair business into the Fender Electric Instrument Company, manufacturing lap steel guitars and amplifiers in a smallish way.

Les’s other guest on those Sunset nights was a more rough-and-tumble figure by the name of Paul A. Bigsby. The eldest of the three men on the patio, he’d certainly done his share of living. A Midwesterner like Les, he was born in Illinois and had moved to California, where he took a few hard knocks and epic spills as a motorcycle racing champion before turning his hand to designing and building them. A skilled machinist, he had eventually gravitated from building motorcycles to lap steel guitars on a custom basis for western swing musicians like Speedy West, Joaquin Murphey, and Noel Boggs. Bigsby was louder than Leo Fender and less suave—if no less outgoing—than Les Paul. A man of action with a big, booming voice and towering presence, he liked to describe himself as a guy who could build anything.

Given their relatively minor stake in the guitar business at the time, Fender and Bigsby were more than happy to travel north to Curson Avenue and pay a call on Les Paul. And they were warmly welcomed. Although the youngest of the three men, Les possessed an innate gift for putting people at ease while slyly making himself the center of attention. He was charismatic, if slightly avuncular, and a natural-born raconteur.

His studio-cum-workshop, out in the garage, was also a big draw. It was here that Les Paul did some of his most significant design work. The garage was cluttered with bulky, arcane, and frequently homemade pieces of electronic gear perched atop assorted items of household furniture. But it was a fully functional studio where Les would do commercial sessions—often with hillbilly and western swing ensembles—as well as record his own music. Leo Fender and Paul Bigsby were more than a little keen to find out what Les was up to in that garage.

“We enjoyed sharing our likes and dislikes in life generally,” Les would later recall of those nights. They’d listen to the group that was currently recording, to the amplifier and the guitar, and talk about what changes they were going to make. “We used to spend hours after a recording session with some hillbillies—you know, country players. We’d sit in the back yard on the patio by the fire for hours and discuss sound.”

To a nosy neighbor peering into the backyard, it may not have looked like much. Just three guys settling into middle age, sitting around and talking shop. But the trio was quietly fomenting a revolution. They’d all been developing an idea that had been in the air for quite a while but had never quite come together until then. The upshot of their work would dramatically affect the sound of pop music, and indeed the tone, tenor, and trajectory of all popular culture in the latter half of the twentieth century and beyond. Each man, in his own way, was laboring to make the solid-body electric Spanish, or standard, guitar a reality. The instrument would become the mainstay of modern rock music and many other popular musical genres.

These days, the Mocambo, the Trocadero, and other hot spots of 1940s Hollywood have long since disappeared from the Sunset Strip. But their place has been taken by equally historic nightclubs like the Roxy and the Whisky a Go Go, where bands such as the Doors, the Byrds, Van Halen, and Guns N’ Roses made rock history for decades, and where today’s and tomorrow’s rock stars still strut their stuff. The stretch of Sunset right around Curson is home to a panoply of guitar shops where rock guitarists and other six-string aficionados flock in search of their dream axe. More often than not, they’re seeking gear that bears the name Fender, Bigsby, or Les Paul.

—

IT’S A POPULAR misconception that Les Paul single-handedly invented the electric guitar, or at least the solid-body electric guitar. While he contributed substantially to the instrument’s development, Les Paul most certainly did not invent the solid-body electric guitar, much less the electric guitar itself. George Beauchamp, Adolph Rickenbacker, Paul Barth, Harry Watson, and Walter Fuller’s enormous contributions to the electric guitar’s early development have been discussed. These men and others—including Lloyd Loar, Paul Tutmarc, and Victor Smith—had made significant progress with the new instrument, both technologically and commercially, well before Les did anything notable with it.

So where did we get this myth of Les Paul’s single-handed creation of the electric guitar, ex nihilo, like Yahweh summoning the cosmos into existence? All too often the source of this creation story was Les himself. He did have a talent for embellishing the truth and rewriting key chapters of musical history with himself as the sole hero. Among his many other gifts, Les Paul possessed that of gab. His easygoing charm and folksy way with a tall tale made people just want to believe anything he said. Maybe it was an artifact of that Depression-era determination to get over by any possible means—to make do, to improvise, to invent if necessary.

Born Lester William Polsfuss in Waukesha, Wisconsin, on June 9, 1915, he displayed both musical and mechanical inclinations from an early age. As a boy, he altered the player piano rolls at home, adding notes that weren’t meant to be there. There’s a story, probably coined by Les himself, that, at around age twelve, he fashioned a homemade electric guitar, amp, and P.A. system using a record player pickup, telephone mouthpiece, and parts from the family radio. “Looking back over my life,” Les said in 1999, “I think I probably spent a little more time tinkering with electronics than I did playing music.”

He played plenty of music as well, first hitting the road at the tender age of thirteen with a cowboy band during a summer break from school. “They were short on hats,” he recalled. “So when it came time to feature me, one of the other guys would give me his cowboy hat and boots. Of course they were way too big. When I went out there to sing my songs, pretty much all you could see was a big hat and a pair of boots.”

Hillbilly and western music were two kindred genres that the golden age of Radio had helped to popularize throughout the twenties. Launched in 1922, WSB in Atlanta was perhaps the first radio station to broadcast this style of music, followed by WBAP out of Fort Worth, Texas, in 1923. The National Barn Dance program, which began broadcasting in 1924 on WLS in Chicago, brought down-home music to millions of listeners. Nashville’s WSM Barn Dance got under way in 1925, and two years later would be renamed the Grand Ole Opry.

By the early 1930s, as Les reached his late teens, he had made his own way onto the airwaves, singing and strumming the guitar under the cheerfully countrified name of Rhubarb Red. Early in the history of broadcast, he appears to have had a keen sense of the new medium’s power, not only to reach a wider audience than a touring musician could ever hope to, but also as a platform for a savvy performer to craft a persona and sell himself as a larger-than-life character.

Rhubarb Red started out on Missouri radio stations KMOX and KWTO, playing sometimes on his own and sometimes in a duo with Sunny Joe Wolverton known as the Ozark Apple Knockers. The Knockers performed on Chicago’s WBBM for several months, as well, before going their separate ways in 1934.

It was as Rhubarb Red that Les Paul made his recording debut on the Montgomery Ward label, in 1937, with a series of sides that included the jaunty “Just Because” and “Deep Elem Blues.” Both tracks adhere to the same old-timey formula—a briskly strummed acoustic guitar accompaniment to verses that alternate melodic harmonica passages with Les’s reedy vocalizing. With the possible exception of a few jazzy passing chords, there’s little indication here of the more uptown musical approach Les would develop in just a few years, although an element of Rhubarb Red’s cornball humor would remain part of his personal style, even after he moved on to slicker musical genres and newer media.

It was during his time in Chicago in the 1930s that Les made one of his first serious forays into electric guitar design. He had teamed up with Carl and August Larson, a Swedish-born fraternal guitar-building team active from the 1890s through the 1940s. Their handmade guitars were marketed under a variety of brand names, including Maurer, Prairie State, Euphonon, Stahl, and Dyer, and are still highly regarded today.

“In 1934 the Cumberland Ridge Runners were working at the same radio station I was at, WJJD,” Les recollected. “I saw that their guitarist Doc Hopkins, and several other country players, were playing a brand of guitar that I’d never seen before. It wasn’t a [C. F.] Martin [& Company brand] or anything familiar. I said, ‘What is that thing?’ ‘Oh, it’s the Larson brothers,’ was the reply. So I had to get my butt over there. To my amazement they were in a barn out in the country, outside Chicago.”

Once he’d tracked down the barn, Les found a sign on the front entrance that simply said PULL THE STRING. He did as instructed. The string triggered a bell in a loft at the top of the barn where the Larsons had their workshop. A man, presumably one of the siblings, stuck his head out of a top window demanding that the visitor state his business. On announcing he wanted to talk about building a guitar, Les was admitted to the premises.

The guy pulls the latch up with a long string. You had to quickly leap in there and the door locks after you. I walk up two flights of stairs, up to the top of the barn. And one of the Larson brothers, I guess it was August or Carl, says, “What do you want?”

“Well, I’d like to have you make a guitar for me.”

“Well, I’m a busy man. Tell me specifically what you want.”

“I’d like one that has a solid top on it. No f-holes in it, and additional frets.”

On describing his concept, Les was asked if he was a player himself. “Oh I play pretty good,” he demurred, picking up a guitar that was lying around and offering a small sample of his technique.

“You’re pretty good,” Larson conceded, “but not as good as Rhubarb Red.”

“You think so?”

“I know so. You ever hear of him?”

“They didn’t even know I was Rhubarb Red!” Les marveled. “I had to explain to them that I used two different names. They didn’t get it anyway, but they made the guitar for me. They made two for me. One I gave to Chet Atkins. The other one, I don’t know what happened to it. Maybe I gave it away when I went to New York later on. But the Larson brothers were just great. I had a lot of fun working with them.”

Les had asked the siblings to build him two or three guitars (accounts vary), each hollow-bodied but with a solid maple top approximately an inch thick, with no sound holes and two pickups. The thick, solid top marks a significant early step in his eventual evolution toward a completely solid-body guitar design. Traditional guitar craft had long favored making the top as thin as possible, supported by the slenderest practicable bracing underneath. (A thinner top will vibrate more, thus creating greater natural resonance.) And guitar tops had always contained one or more sound holes to maximize projection from the hollow body. The instruments the Larsons built for Les took a different tack—minimizing the natural vibration of the wooden top, thus allowing the electronic pickups to do more of the work of generating the instrument’s tone.

It also was during this time in Chicago that Les began to move away from the hillbilly-inflected sound of his Rhubarb Red persona, in favor of a more sophisticated jazz guitar style that was gathering momentum. And so Lester Polsfuss rechristened himself yet again—now as Les Paul—creating a more sophisticated persona to complement his new musical direction. There was, however, a transitional period when the guitarist’s two identities coexisted, somewhat schizophrenically, side by side.

“In the daytime, I made money playing country music on the radio,” Les would later explain. “At night, I played jazz. You didn’t make much money playing jazz but you learned so much. That’s when I had the privilege of learning from Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum…all the greats. Chicago was the place to lock into jazz.”

Chicago, in 1937, was where the first of many Les Paul Trios was formed, with upright bassist Ernie Newton and rhythm guitarist/vocalist Jimmy Atkins (elder half brother of guitar legend Chet Atkins). Subsequent lineups and instrumentation would vary, but Les Paul was always heavily featured on electric guitar—playing either one of the many commercially available hollow-body electric guitars then available, or various instruments he had built or modified over the years. The small-ensemble format seemed to suit Les as a player. It was also a harbinger of things to come; small combos would eventually eclipse the big bands of the day. That was, in part, a result of the increased capacity for volume and wider tonal range of the guitar in its emergent, electrically amplified form. In fact, the New York chapter of the American Federation of Musicians came out against the electric guitar in the 1930s, for fear that it would put horn players and other musicians out of work. But ultimately there was no stopping the electric guitar’s rise to prominence.

—

WITH ITS THRIVING jazz scene and vibrant nightlife, mid-thirties Chicago may have been exciting to a young musician, but Les soon had his eyes on a destination that promised even greater thrills. On the strength of his ambition and a tall tale to his bandmates, Les Paul persuaded his trio to try their luck in New York.

“I told them, ‘I know all kinds of people in New York.’ I was lying like hell. I didn’t know anyone, but I didn’t want to tell that to the other guys.”

So, in 1938, the trio relocated. It didn’t take long for Les to make good on his promise, wangling a regular thrice-weekly spot for the trio on bandleader Fred Waring’s radio program, The Chesterfield Hour (sponsored by a leading cigarette brand of the day). Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians were one of the top orchestras of the era, and the show’s presenter, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), was not only America’s first coast-to-coast radio network, launched in 1926, but also one of only three major networks at the time.

Not all listeners responded favorably to the new act coming across NBC’s airwaves. Some wrote in to complain about the strange and, to their ears, unpleasant sound of the newfangled electric guitar Les Paul was playing. There were demands to fire him, or at least rein him in. But Waring stuck by him, and slowly but surely the radio audience adjusted to the hollow-body electric guitar’s timbres. Some may have persisted in their complaints, but others wrote in to say they liked what they heard.

Les Paul had hit the big time. Then as now, New York was a fertile environment for new ideas in music, and Les found himself hobnobbing with Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt. He and his fellow guitar players would gather at the Epiphone guitar showroom on Fourteenth Street, or Eddie Bell’s New York Band & Instrument Company on Sixth Avenue and Forty-sixth Street, where they could exchange ideas and play the newest guitar gear.

While Les may have enjoyed the company, he found that the new equipment just didn’t suit his needs as a player. The archtops typically favored by jazz guitarists—those hollow-body guitars that took inspiration from violin making—came with their own inherent set of liabilities. Stated in the simplest terms, they resonated too much. Resonance—natural vibration of the instrument’s wooden body—is a good thing in unamplified guitars. But with the addition of electronic amplification, all that resonance can create a “woofy” tone that’s hard to control or subdue as volume increases. At higher volume levels, hollow-body guitars are highly prone to feedback—the “howling” sound that results when the pickups start interacting with the amplifier’s speakers, setting up what’s called a transduction loop. In future generations, guitarists like Pete Townshend and Jimi Hendrix would find creative musical uses for feedback. But to players in the late thirties and early forties, it was still very much to be avoided.

So Les decided to push forward with the concept he’d been exploring with the Larsons, and which had been incubating among guitarists and builders for more than a decade—an electric Spanish guitar with a partially or completely solid body.

“When I started fooling with guitars back in the 1920s it was all about, ‘What if we could hear the string all by itself?’ ” Les said.

We know that a hollow-body guitar has an acoustic chamber that is resonating at different frequencies. But what if we could isolate the string from that? If you could take the string all by its lonesome, with nothing sustaining it but the nut and the bridge, what would this honest-to-God string sound like? Is it something we would want to hear? Could the sound be manipulated electronically in some way? That was the challenge: to take a string that was completely divorced from the body and make it sound better, or at least just as good.

And so, starting sometime in 1939, Les decided to put his theory into practice. He got hold of a solid, 4"x4" slab of pine, roughly the length of a conventional archtop guitar body (about 20 to 22 inches). To this he attached a bridge, two wood-covered pickups that he made himself and, also of his own making, a crudely wrought vibrato tailpiece (which anchored the strings and allowed for bending the pitches of notes). To the upper portion of the pine slab he affixed a Spanish guitar neck.

Attachable to either side of the pine block were two “wings” of an Epiphone hollow-body archtop guitar—an instrument whose body he had sawed in half the long way, in the direction that the strings run. These may have been added to the instrument as an afterthought, to make it look more like a conventional guitar, and also perhaps to make it easier to hold in the seated playing position.

The “Log,” as it came to be known, is a true work of bricolage—a folk-art assemblage of spare parts and found guitar artifacts. It was a testament to Les’s resourcefulness and creativity, and one of his most important inventions. But the most important question still remained: Would it play? Les strung it up and plugged it into one of the amps that was in use for his hollow-body guitars, and he found, much to his satisfaction: the thing actually sounded pretty good. It can be heard on several of his classic recordings, including “Lover” and “Lady of Spain.”

Les would later recall the reaction his homemade guitar elicited when he brought it to a jam session prior to adding the body “wings.” “I took it to a bar out in Sunnyside [Queens, New York],” he told Guitar Magazine, “and when I sat in with just the four-by-four they laughed at me! When I put the wings on, they thought it was a guitar and everything was fine.”

In a way, the Log was a successor to the guitar made by the celebrated nineteenth-century luthier Antonio de Torres, who fashioned his instrument’s back and sides out of papier-mâché in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the thin wooden top and bracing pattern he’d devised. The back and sides of a hollow guitar are superfluous, Torres was, in effect, saying. You can make them out of anything. It was the vibrational qualities of the top of the guitar, the part that faces a guitar’s audience, and its bracing that created the instrument’s beautiful tone.

Les’s Log, like Torres’s papier-mâché guitar, is a demonstration instrument, although it demonstrates a different acoustical principle. In an amplified setting, the traditional guitar’s hollow body and thin, resonant top become superfluous—or, even worse, a liability. In other words, the vibrational qualities—or the relative lack of vibration—exhibited by a solid chunk of wood lend themselves to amplification better than those of a hollow box.

And if you get rid of the box, then why couldn’t your electric guitar be shaped like pretty much anything? The elongated rectangle of the Log’s central body-block eloquently—if somewhat inelegantly—demonstrates this. The traditional guitar shape can be discarded. (Luthiers in subsequent decades would run wild with this idea, as we’ll see.)

Though Les didn’t go out of his way to dispel the notion that he was the first electric guitar builder, the truth is that his Log had its predecessors. George Beauchamp had attached a guitar string and a very primitive pickup to a solid chunk of 2"x4" wood, way back in the late twenties. But his prototype didn’t work very well, and he had been aiming to create an electrified Hawaiian steel guitar, not an electric Spanish guitar like the Log.

The Log, in contrast, became one of Les Paul’s main working instruments for years to come. Of course, if he had not gone on to lend his name to a Gibson electric guitar—an instrument, incidentally, that he did not design, but that would become hugely popular in subsequent decades—the Log might have been a mere footnote in musical history. But as it is, that prototype is regarded as a major milestone in the development of the solid-body electric Spanish guitar. As an indicator of the Log’s historic importance, it is now enshrined in the Country Music Hall of Fame’s collection of iconic musical instruments.

—

NOT THAT THE world instantly recognized Les’s genius. He had been doing some of his work on the Log at the Epiphone guitar factory in Lower Manhattan. Noted for its stylish jazz archtops, Epiphone was one of the top guitar manufacturers and a major rival of Gibson. Les would later remember Epiphone chief Epi Stathopoulo’s less-than-enthusiastic reaction to his new instrument: “Epi looked at me and said, ‘What in the hell are you doing?’ I spent a few Sundays at the Epiphone factory making that thing. They were all curious to see what I was up to. And when I got done making it, the only ones who liked it were the night watchman and me. No one was very impressed with it.”

Nor was Gibson interested in the Log when Les brought it to the company’s Kalamazoo, Michigan, headquarters at some point in the forties, hoping to partner with them on a commercially produced solid-body electric. Gibson was then enjoying huge success with its hollow-body archtop electrics and saw no reason to take a chance on a solid-body contraption. Les was reportedly dismissed by Gibson president Maurice H. Berlin as “that character with the broomstick with a pickup on it.” Years later, Berlin would confide to him, “We laughed at you for ten years.”

While accounts vary—as they often do in Les’s case—Les claimed that he first brought the Log to Gibson in 1941, which would have been a singularly bad moment to embark on a risky new business venture. It was the year that the United States entered World War II. Wartime shortages of materials curtailed productivity for many manufacturing industries. Factories were commandeered and converted into manufacturers of war supplies. As a result, a number of guitar companies were forced to fold. Even a major player like Gibson would emerge from the war years seriously hobbled. The solid-body electric guitar would have to wait nearly another decade to take flight.

Fortunately, Les Paul had other fish to fry. While passionately interested in the idea of a solid-body electric guitar, his creativity had further avenues to explore. It was also in 1941 that he acquired another electric guitar—a hollow-body this time—that would become a key element in his recorded sound during this period. He was in Chicago doing some radio work when a man approached him with an Epiphone guitar and an amp.

“The guy told me that he’d got his hand caught in a bread wrapping machine at work and he’d mangled it badly,” Les recalled.

He said, “I can’t play guitar anymore, and I’d like you to have this guitar and amp.” Well, that guitar and amp were to become history. I said to myself, “I can operate on this guitar. I can cut it all up. It’s a guitar I don’t care about. I’ll make it different than any other guitar I got, and I’ll do some of the things I always wanted to do but couldn’t.” This one had a hole in the back of it, so I could go in there and do a hysterectomy. It was called the Clunker.

This guitar would be the first of several “Clunkers,” hollow-body electrics that became platforms for design experimentation. Les Paul was a key originator of the concept that an electric guitarist could—and should—make modifications to his instrument in pursuit of a sound uniquely his own. Seen from this perspective, electrical and mechanical engineering of both the guitar and amplifier are an integral part of the electric guitarist’s art—a creative resource to be pursued just as avidly as playing technique or any other traditional musician’s skill. Following in Les’s wake, many of the greatest electric guitarists, from Pete Townshend to Eddie Van Halen, would become not only virtuosos but technical innovators of the instrument and its amplifier.

Like most of Les’s guitars, the Log and the Clunker would undergo a process of constant rewiring, revamping, and revision as their owner experimented with new sonic ideas. And those ideas weren’t flourishing in isolation. His thoughts on the electric guitar were starting to converge with those of others. The instrument’s dramatic moment of cultural ascendancy was right around the corner.

—

THE LOG AND the Clunker served Les well in his new home: Hollywood. He and his trio relocated there in 1942, and the city proved to be just as good to the guitarist as New York had been. Before long, the Les Paul Trio was backing Bing Crosby. A well-groomed, personable singer, film actor, and all-around entertainer with a massive fan base, Crosby was one of the first true pop stars of the modern era, and Les’s work with him brought only greater attention to the guitarist.

“Bing just loved the guitar,” Les would later recall. “He would lay down on the floor and put his head right near [the guitar amp] speaker. And there was eight hundred people in the audience, and they’d watch Bing.”

The Les Paul Trio’s first recording with Crosby, “It’s Been a Long, Long Time,” became a hit for Decca Records in 1945. The record showcases Les’s considerable talents as an accompanist, his lyrical electric guitar lines echoing and answering Crosby’s wistful baritone voice in graceful counterpoint. It was the start of a long and successful relationship with both Crosby and Decca.

Les also recorded with the popular singer Helen Forrest and “America’s Sweethearts,” the Andrews Sisters. He toured with Crosby and the Andrews Sisters as well, and was also quite active in radio during this period. NBC placed him in charge of several shows, some featuring jazz and others country. Searching for a singer for one of his country spots, he was introduced to Colleen Summers. The two hit it off and would later marry and record together as Les Paul and Mary Ford. (The latter name is one that Les found in a phone book and subsequently copyrighted. Stage names mattered a lot to him.)

The Les Paul Trio would also cut many instrumental recordings of their own for Decca. These included jazzy arrangements of such standards as Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine” and Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies,” as well as a selection of Hawaiian and country music. A number of the Decca sides, such as 1947’s “Guitar Boogie,” “Steel Guitar Rag,” “Caravan,” and “Somebody Loves Me,” feature another innovative electric guitar that Les designed—a headless aluminum model. Tonally, the guitar didn’t sound much different from other electrics he played at the time—clean and crisp, a little lacking in low-end warmth, perhaps all the better to articulate Les’s extremely nimble and inventive playing style on these tracks. The fact that this aluminum guitar sounded so similar to ones made of wood only served to underscore Les’s central premise that the sound of an electric guitar comes principally from the electronics rather than the body. The metallic instrument worked well in the studio but not onstage, where hot theatrical lighting caused the aluminum to expand, thus throwing the guitar out of tune.

Always a staunch supporter of Les’s experiments with music technology, Bing Crosby offered to set him up in his own recording studio and music school, Les Paul’s House of Sound. But the guitarist declined, preferring to put together a studio in the detached garage of his home on Curson Avenue. Musicians today commonly have their own home recording studios; Les Paul was an early pioneer of the practice.

Curson Avenue is also where he began to make some of the earliest known experiments with multitrack recording, using not tape but a disc-cutting lathe he built with the flywheel from a Cadillac and outfitted with multiple cutting heads. Les says he was playing around with “disc multiples” (his term for what we call multitracking) as early as the thirties, but by 1946 all the pieces were in place for him to exploit these technological innovations in a major way. He discovered, for instance, how to create echo effects using the record and playback heads of his recording machine, thus pioneering the use of what is now called slapback echo. This is the “hiccupping” sound later to become a mainstay of rockabilly and other early rock and roll, created as the audio signal is reproduced by the playback and recording heads in rapid succession.

The catalyst that led Les to deploy all these developments in a single recording was a comment made by his mother—and frequent career advisor—Evelyn Polsfuss:

She said, “Lester, I heard you playing on the radio this afternoon and you were great.” I said, “Maw, I wasn’t on the radio this afternoon.” And she says, “Well, you better do something because everybody else is getting to sound like you!” So I went back to Hollywood, got in that studio and said, “I’m not gonna come out of here until I got a sound that’s so different that my mother can tell me from anybody else on the radio.”

The result was “Lover,” a tour de force of glycerin guitar work performed on the Log and the Clunker. A tipsy waltz-time intro gives way to a frenetic up-tempo reading of the old Rodgers and Hart standard that might have been beamed in from another galaxy. The arrangement’s giddy, high-pitched arpeggios and crazy chromatic runs sound as if Les’s guitars had inhaled a massive breath of helium. The track still comes across as delightfully bizarre today. One can only imagine how strangely it must have struck listeners in the forties. “Lover” introduced the world at large to the wondrous array of sounds that could be generated by the creative manipulation of recording technology. In addition to echo, there was varispeeding—the helium effect produced by increasing the speed at which the tape passes over the playback head—and overdubbing, the process of piling one sound on top of another by means of multiple tape tracks.

This was the principle of musique concrète—the tape-manipulated art music developed by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen—applied to pop music. “Lover” also gave birth to the concept of the electric guitarist as studio auteur, manipulating guitar effects and the multitrack resources of the studio itself to build a beguiling sonic landscape. Les Paul was one of the first musical artists to intuit that the best use of a recording studio might not be simply to document a live performance but rather to serve as a workshop for building audio collages track by track. And because the electric guitar, by its very nature, produces an electrical signal rather than an acoustic sound, it made for an ideal and infinitely malleable input device for the studio’s array of magical effects.

This insight would go on to provide tremendous inspiration for Jimi Hendrix, Brian May of the band Queen, and a host of other classic rock guitarists who employed the recording studio in this painterly way. One of these six-string titans, Jeff Beck, was just six years old when he heard Les Paul recordings such as “Lover” and its follow-up, “How High the Moon,” for the first time on BBC Radio.

“I remember the sound was fantastic, especially the slap echo and the trebly guitar,” Beck told Guitar World magazine in 2009.

I had never heard an instrument like that before. Up to that point, all I listened to were marching bands from World War II and dance orchestras that played music to entertain housewives. All of a sudden this scatty guitar came over the airwaves. To a kid like me, who had been around music all of the time, it sounded so different. It still sounds fresh today compared to contemporary music, so imagine what it sounded like compared to a bunch of trombones. It just leapt out of the speakers.

“Lover” seemed sufficiently weird to Decca that they refused to put the track out, which led Les to sign a new deal with Capitol Records. Released in 1947, “Lover” was billed as introducing “Les Paul’s New Sound.” It did much to foster public perception of Les as the high-tech Svengali of the electric guitar—“The Wizard from Waukesha,” as he became known. It also inaugurated a long string of Les Paul and Mary Ford hits for Capitol. Mary served as a highly accomplished rhythm guitarist as well as lead vocalist on many of these recordings. She and Les seemed the ideal duo, musically as well as romantically.

“She was a very fine musician,” Les said of Mary. “A very fine singer. Had a great ear, too. Tremendously talented gal. I had all the luck in the world.”

But this run of good fortune came perilously close to a premature and permanent end. Les was involved in a serious auto accident in 1948. His right arm was broken in such a way that the elbow joint was rendered incapable of motion. At one point, the doctors thought they would have to amputate the arm. Les later claimed that he started working on ideas for a guitar synthesizer at this time, searching for a way to be able to continue making music with just one arm.

“That wouldn’t have fell together had they not said they were gonna amputate my arm. After the automobile accident, they said, ‘Sorry.’ I said, ‘Don’t feel sorry. I’ve already thought of an idea.’ So I got a pencil and paper and with my left hand started to draw out a synthesizer.”

Luckily, Les got to keep his right arm. With characteristic determination, Les had the doctors set his broken bones in such a manner that his partially immobilized arm would always be in position to pick a guitar. He later claimed that he’d abandoned the guitar synth idea because his hands were full with other commitments and inventions. Was the whole thing another one of his tall tales? It’s hard to say.

Meanwhile, Les’s old friends Leo Fender and Paul Bigsby were starting to come into their own. They too were making discoveries about pickup design and the other topics of discussion on those late-forties Hollywood nights, out on the patio at Les’s Curson Avenue house. Fender and Bigsby were poised to take center stage as the forties gave way to the fifties. But Les wasn’t about to let them hog the spotlight for too long. The world hadn’t heard the last of Les Paul.

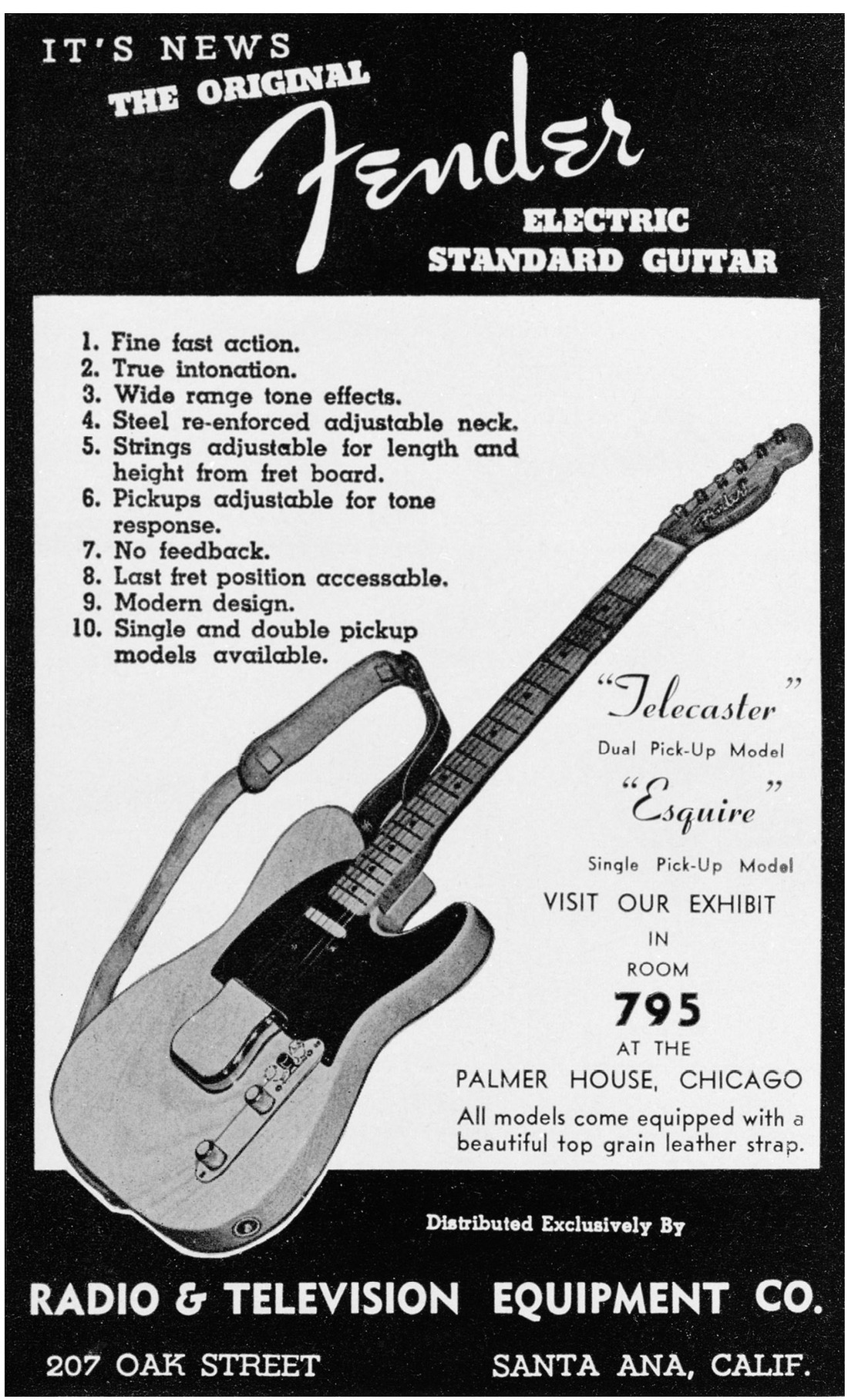

A trade ad for the Fender Telecaster and Esquire