Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound, and Revolution of the Electric Guitar - Alan di Perna, Brad Tolinski (2016)

Chapter 9. ERUPTIONS

In his 1976 essay written for New York magazine, celebrated American social critic Tom Wolfe defined the seventies as the “Me Decade.” He described how U.S. economic prosperity had “pumped money into every class level of the population on a scale without parallel in any country in history,” triggering a wave of narcissistic behavior resulting in “the greatest age of individualism in American history.” The years immediately preceding Wolfe’s piece had marked a grim moment in American history. The early seventies had been dominated by headlines on the Watergate scandal, undermining the average citizen’s faith in his or her elected officials; the trial of the Charles Manson family, who had brutally murdered pregnant actress Sharon Tate; and the catastrophic last days of the Vietnam War. The Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC)’s 1973 embargo of oil to the United States, in response to American involvement in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, caused the price of oil to soar from $3 per barrel to nearly $12, sending shock waves through Wall Street as the stock market plummeted and inflation skyrocketed.

But after Nixon announced his resignation in 1974 and the war in Vietnam came to its end in 1975, spirits, it seemed, began to lift. Escapism prevailed at the box office: Star Wars, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Blazing Saddles, Smokey and the Bandit, and Animal House were among the top ten grossing films of the decade, and some of its most remembered. Style veered toward the ostentatious: this was the era, after all, of widened lapels and platform shoes, as clothing simultaneously became skimpier and more formfitting. Cocaine took its place as the hyper drug of choice among young adults, with cocaine initiation rates soaring across the decade, reaching their peak in the early eighties. Perhaps the most appropriate emblem of the era was American graphic artist and ad man Harvey Ball’s “smiley face”; its yellow visage could be seen grinning out from T-shirts, coffee mugs, and underwear. Though the news continued to bring its daily onslaught of tragedy, there was still a distinctive, inescapable sense, particularly among the young, that a corner had been turned.

It was a stark contrast to the mood across the sea, where England continued to struggle economically. Its industrial-based economy was in a tailspin, unemployment ran rampant, and inflation peaked at over 30 percent. Under these circumstances, it was no surprise that teens and young adults had become restless, angry, and cynical, their rage manifested in the punk rock movement that soon ruled Britannia.

American critics loved the anger and raw energy of U.K. bands such as the Sex Pistols, the Damned, and the Clash. But if record sales were any indication, most American kids weren’t feeling the angst. In 1978, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, perhaps the most important punk rock album of the era, failed to dent Billboard’s Top 100, while that same year, the soundtrack to the John Travolta movie Saturday Night Fever, featuring the dance music of the Bee Gees, stayed atop the album charts for twenty-four straight weeks, selling 15 million units. And if it was rock and roll you were after, nonthreatening corporate rockers Journey, Foreigner, Boston, and Meat Loaf, whose 1977 Bat Out of Hell album would eventually sell over 43 million copies worldwide, were there to satisfy you.

If you were eighteen and lived in Hollywood, California, you had likely begun hearing of a hard rock band from Pasadena that had recently arrived on the scene, poised to eclipse those more tepid bands. Memorably described by Los Angeles producer Kim Fowley as the musical equivalent of “a six-pack of beer, cruising down the highway with a big-breasted woman while running over animals,” Van Halen was the ultimate party band, packing in fans at clubs on the Sunset Strip like the Starwood, the Whisky a Go Go, and Walter Mitty’s Rock & Roll Emporium, where 300-capacity rooms were often illegally stretched to accommodate a thousand sweaty kids. Keeping with the spirit of the times, the band could switch at the drop of a dime between playing the classic hard rock of Led Zeppelin and disco hits like “Get Down Tonight” by KC and the Sunshine Band, while somehow retaining their own loose, hip, and happy sound. Their lead singer was a larger-than-life, motormouthed dervish, but the band’s main attraction was undoubtedly their young guitarist. For almost five years, word of his otherworldly playing had been burning up West Coast high school hotlines, and his club performances became legendary among local musicians. His approach to the guitar was so radical and exciting, it bordered on magic. Even professional guitarists who went to see him struggled to explain how this kid with the perfect hair and the “What, me worry?” grin was creating the torrent of lightning-fast licks, strange ringing harmonics, and screaming whammy-bar dives. To those who flocked to see him, one thing was clear: he was the real deal—the next Jimi Hendrix or Eric Clapton.

Listeners packed into those Hollywood clubs could only wonder: Who the hell was this remarkable kid, and where on earth did he come from?

—

EDWARD LODEWIJK VAN HALEN moved to Pasadena, California, from his native Nijmegen, Holland, when he was seven, along with his parents and his older brother, Alex. When they arrived in 1962, Ed remembers, the cash-poor family had only “$25 and a Dutch-made Rippen piano,” and what little of the former the family had went into teaching the children how to play the latter.

By all accounts, those early years in the United States were not easy. Ed’s dad, Jan, was a professional musician who played saxophone and clarinet in wedding bands at night, but kept janitorial day jobs to make ends meet. Life for the boys wasn’t much easier.

“When I came to this country I was scared,” remembers Eddie. “I couldn’t speak the language. I used to get the shit kicked out of me by white people, so to speak. I was a minority. My earliest friends were black kids in the neighborhood. I didn’t have to manufacture pain to create.”

Alex was the more extroverted of the two boys and worked hard to fit in, while Ed tended to retreat into a world of his own—a world of music. Both boys were trained to play classical piano, but young Edward excelled, winning trophies in local music competitions. Neither particularly enjoyed the music they were being asked to play—they were more attracted to rock bands such as the Dave Clark Five, the Animals, and Cream—but they learned fundamentals that would serve them well in the ensuing years: rhythm, harmony, left and right hand independence, and steely discipline.

Alex eventually drifted toward the guitar, while Ed started banging away at drums. In a cosmic stroke of luck, they decided to trade—or at least Ed was forced to defer when his older brother became more interested in pounding the skins.

“When I first picked up the guitar there was no message from God or anything,” Eddie told Guitar World. “Some things were easy, some things were hard. But I didn’t even think about whether it was easy or hard; it was something I wanted to do, to have fun and feel good about doing it. Whether it took me a week to learn half a song or one day to learn five songs, I never thought of it that way.”

Those days and weeks melted into years, as the shy, gifted young man’s guitar playing continued to improve. “I used to sit on the edge of my bed with a six-pack of Schlitz Malt talls,” he said. “My brother would go out at 7 p.m. to party and get laid, and when he’d come back at 3 a.m., I would still be sitting in the same place, playing guitar. I did that for years.”

More than a few of those long practice hours were spent thinking about aspects of the instrument that most simply took for granted. “Since the beginning, everything I picked up off the rack at a music store—even the custom-made stuff—did not do what I wanted it to do,” Van Halen said years later. “Either it didn’t have enough of something, or it had a bunch of Bozo bells and whistles that I didn’t need. A lot of it had to do with the fact that I never took guitar lessons, so I didn’t know right from wrong. I didn’t know there were rules; I just knew what I liked and wanted to feel and hear.”

His tinkering with instruments began early on:

I bought one of my first guitars from Lafayette Electronics, which was like a Radio Shack. They had a 12-string guitar that I really liked, but I didn’t want 12 strings; I wanted six. I asked the guy if I could take six off and try it out, and he said, “No.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “If you buy it, you can do whatever you want.” So I bought it, took six strings off and I loved it! And that was my very, very first successful attempt at changing something that was considered standard to my liking.

Later, Van Halen got more daring with his experiments. After purchasing a rather pricey goldtop Les Paul, he fearlessly took a chisel to the vintage instrument, and replaced the bridge pickup with a louder and more powerful humbucker stolen from one of his other guitars. Then he decided he wasn’t a fan of the instrument’s gold finish, so he stripped it and repainted it black. The modifications gave Edward more of what he wanted and was a hint of things to come, including the striped paint job that you see on most of his guitars since the band’s first album.

Edward destroyed a lot of instruments trying to get them to do what he wanted, but he learned something from every guitar he tore apart, and discovered even more things in the process.

But why did he have to go to so much trouble to create the guitar of his dreams in the first place? Part of the answer was simply Van Halen’s idiosyncratic brand of DIY genius; he refused to be constricted by the equipment that was available. But the rest points to a story with implications far beyond Southern California.

—

LEO FENDER WAS a creative genius and a driven perfectionist, but his run with Fender was coming to an end. A series of strep and sinus infections throughout the fifties and early sixties, along with the stress of running his growing empire, had left him fatigued. Sometime in the mid-sixties, Leo instructed his associates to start looking for someone to buy the company he had built, which had by then expanded to more than five hundred employees occupying twenty-seven buildings in Fullerton.

It didn’t take long to find an interested party. In 1965, national and multinational conglomerates had become increasingly significant parts of the American economy. Historians and economists have since identified the fertile period between 1965 and 1969 as the Third Merger Wave, due to a strong economy that gave many firms the resources necessary to acquire other companies. (The conditions were uncommon—the last merger wave had taken place in the twenties.)

Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. (CBS), the radio and television media giant, was just one of the businesses eager for diversification, and they saw in Fender an opportunity. So, for an impressive $13.5 million (roughly $80 million by today’s standards), CBS acquired Fender in early 1965. Considering both companies’ ties to the entertainment industry, it seemed like a fine match. And it was—but only for a hot minute.

Within months, CBS started intensifying production and slashing costs. In their first year, they increased Fender’s guitar and amplifier output by about 30 percent, and a scant year later they erected an enormous new Fullerton-based facility and increased productivity by an additional 45 percent.

The rapid expansion came at a cost. By 1966, CBS was instituting changes that started to negatively impact the feel and quality of Fender instruments and amps. Their most popular guitar—the Stratocaster—was the first to get hit in the twang bar. The guitar’s sensuous curves suddenly became less contoured and sleek, and cheaper plastics were used for the pickguards. Indian rosewood supplanted the beautifully figured Brazilian rosewood on the fingerboards, and quality control went out the window.

In 1968 the thin, nitrocellulose lacquer that had been used on every Fender guitar since the early fifties was changed to the cheaper polyurethane. By 1971 the desecration was complete when the Strat was given a three-bolt neck (instead of the conventional four bolts), and bridge saddles fashioned from a cheaper alloy in place of the original pressed steel, all of which contributed to a less lively sound. Eventually CBS started slashing away at product lines; by 1980 they’d eliminated Esquires, Duo-Sonics, Jaguars, Jazzmasters, and thinline Teles, while also purging the majority of Fender’s distinctive custom-color options.

To this day among guitar collectors, the term “pre-CBS” is used to describe a utopian world where the just ruled, the righteous prevailed, and all instruments achieved a sort of platonic ideal. “Post-CBS,” on the other hand, is a demarcation uttered with the kind of disdain usually reserved for traditional Chinese curses.

Gibson, too, was undergoing extraordinary changes—and not for the better. In December of 1969, Ecuadorian Company Limited (ECL), a South American beer and cement conglomerate, purchased the Gibson parent company, Chicago Musical Instruments. Perhaps their name was a touch too exotic for U.S. consumers; it was quickly Americanized to “Norlin.” The acquisition spelled disaster for the brand.

It would be a stretch to suggest that no great guitars were built during the seventeen-year Norlin era, but it is remembered as a time of missed opportunities, questionable quality control, and downright weird and unpopular products such as the Marauder, an awkward Les Paul/Telecaster hybrid with a Flying V headstock; or the RD, a hideous variation on the Gibson Firebird with electronics designed by synthesizer guru Bob Moog. Among their most egregious acts, however, were the indignities heaped on the once-mighty Les Paul.

The original single-cutaway Les Paul Standard was an instrument that was just slightly ahead of its time. Prematurely discontinued in 1960, it experienced a spectacular revival four or five years later, as we’ve seen. While any reasonable company would’ve responded by immediately putting the instrument back into production, Gibson hesitated. When they did finally respond, it was with “the Deluxe,” a half-assed variation on the Standard.

Players immediately took offense at the fact that the guitars they were being marketed looked different from the ones their heroes were using. But that was just the beginning. Like the Stratocaster, the Les Paul would be subjected to other detrimental changes, both cosmetically and in construction, and it would take years before the company rectified these injustices.

In the meantime, vintage guitars were all over the pages of music papers, becoming almost as recognizable as the players, and were coveted by musicians the world over.

With the corporate heads at Gibson and Fender turning a tin ear to consumers, a number of manufacturers, big and small, started to see opportunity. As the Japanese were seizing upon weakness in the “Big Three” American automakers, grabbing market share with their sturdy and inexpensive products such as the Honda Civic, something similar was happening to the U.S. guitar industry. Due to a lack of legislation to address patent infringements and restrict import sales, a boatload of high-quality Les Paul and vintage Stratocaster knockoffs, produced by overseas manufacturers, hit the shores in the 1960s and ’70s. And players took notice. Japanese manufacturers, including Tokai, Fernandes, Burny, Ibanez, Univox, and Aria, flooded the U.S. market with excellent instruments at reasonable costs. Also sensing gaps in the marketplace were new American companies like Peavey, Music Man, Heritage, and B.C. Rich, who began to take flight themselves.

While these enterprising start-ups posed legitimate threats to the established companies, most players still lusted after the brands their heroes used. And if they couldn’t buy those discontinued treasures, maybe they could improve the subpar Strats they already owned.

—

ONE OF THE inevitable results of the decline of Fender and Gibson in the seventies was the creation of the “aftermarket replacement parts” industry—an unsexy name for a resourceful group of independent tinkerers who started making guitar parts and accessories that improved inferior factory-made instruments.

Leading the charge of this revolution was a young Staten Island, New York, musician and guitar technician named Larry DiMarzio, who built his first Super Distortion pickup as a replacement for factory Gibson humbuckers in 1972.

“I started building my own pickups for the most practical reason,” DiMarzio says. “I wanted my guitar to sound better. I wanted to get a bigger sound than what I was getting out of the standard pickups of the day. It turns out others did, too.”

Most of DiMarzio’s early marketing was by word of mouth on a local level and via small mail-order-only ads, placed in the back of national music magazines and announcing “The Hottest, Loudest, Longest-Sustaining Pickups Ever Made!” True to his claim, his humbuckers, with their increased output level, made almost any Les Paul roar.

It didn’t take long for the word to spread among East Coast guitar cognoscenti. Soon the hottest players in the land, like Kiss’s Ace Frehley and jazz virtuoso Al Di Meola, were beating a path to DiMarzio’s modest door.

“I worked at the Guitar Lab on 48th Street in Manhattan,” he said. “We’d get in a new Les Paul and remove the heavy gauge strings, then grind and polish the frets because the factory hadn’t done this properly, and make a total readjustment.” Soon he was also adding his own pickups to the mix, trying to extract from inferior instruments the kinds of sounds produced by the classic guitars owned by Eric Clapton and Mountain’s Leslie West.

Over the next decade, many other enterprising technicians and luthiers got into the act. After spending time in London and doing repairs for Jimmy Page, George Harrison, Jimi Hendrix, and others, a New Jersey native named Seymour Duncan eventually settled in California and started his own very successful replacement parts company in late 1978.

So did another talented West Coast guitar entrepreneur named Wayne Charvel, who became a local legend in the early seventies for his repair work and stunning custom finishes while employed as an independent contractor for Fender. In 1974, Charvel opened a shop of his own in Azusa, California, and commissions flowed quickly from gigantic bands such as Deep Purple, ZZ Top, and the Who.

Wayne’s insider perspective and expertise allowed him to identify common problems and gaps in the market, and he, like DiMarzio, eventually started his own mail-order business that sold guitars as well as his unique inventions, such as a stainless steel tremolo arm for Stratocasters that was four times stronger than the originals. To supplement his business, he enlisted two talented woodworkers—Lynn Ellsworth, who would go on to start Boogie Bodies, and Dave Schecter, who later founded Schecter Guitar Research—to craft bodies and necks with the kind of elegance and precision no longer being offered by the big manufacturers.

But perhaps Charvel’s canniest recruit was not an employee but the inquisitive and enthusiastic young musician who regularly haunted his California repair shop, and whom he had taken to mentoring. Eddie Van Halen was still a couple years away from superstardom, and he often visited Wayne’s world in the mid-seventies. Sometimes he would boldly pepper Charvel with questions on guitar repair. On other occasions he’d quietly hang out and absorb information that he would use to create his own spectacular innovations—inventions that would eventually put the replacement parts industry on the map for good.

“The first time Ed came in he asked me if I could stop his DiMarzio pickup from squealing,” said Charvel.

I told him I could. I showed him a trick I learned from an electronics genius I knew named Bob Luly, where you soaked the pickup in hot wax, which is now commonly referred to as “potting.” To the best of my knowledge, we were the first to “pot” after-market pickups…

After that, Eddie would come by the shop a lot, and sometimes he would sit on the floor and play the guitar while I repaired some of his other guitars.

—

THE STORY OF how Ed built his iconic red, black, and white striped “Frankenstein,” or “Frankenstrat,” guitar—one of the most famous guitars in rock history—has often been riddled with errors, many perpetuated by the guitarist himself in an attempt to throw copycats off his trail. However, in recent years, he’s opened up about his legacy. As Eddie explained to Guitar World, the guitar was the product of years of trial and error.

After working on his goldtop Les Paul and getting a taste for guitar modification, Eddie acquired several other guitars that he would put on the operating table, including a 1961 Gibson ES-335 and both 1958 and 1961 Fender Stratocaster guitars. “That 335 used to be my favorite guitar, because it had a thin neck and low action,” he said, referring to the close proximity between the guitar’s strings and its fretboard. “It was real easy to play, but the guys in the band hated how it looked.”

One can only imagine what his group thought after Edward performed some major surgery on the hapless guitar. Frustrated by the fact that the ES-335 would go out of tune every time he depressed the instrument’s vibrato arm, he took a hacksaw and cut the tailpiece (which anchors the strings to the guitar’s body) in half so only the higher three strings would wiggle when he used his whammy bar. “That way I could always go back to the three lower strings to play chords if the vibrato made the high strings go out of tune,” said Van Halen. “People tripped out on that, but I’d try anything to make something work.”

As whammy-bar dives became a greater part of his playing style, Van Halen discovered that the Fender Strat’s vibrato system was easier to keep in tune. Unfortunately, his picky bandmates considered the Strat’s tone too thin. Eddie had a solution to that dilemma: he routed out the body of his ’61 Strat and installed a fat-sounding Gibson PAF humbucker in the bridge position.

“I slapped a humbucker in there and figured out how to wire up the rest of the shit,” he said. “That got me closer to the sound I wanted, but it still wasn’t right. The tone was still too thin, probably because of the wood that the body was made of.” After months of experimentation and frustration, Ed decided to start from scratch and build his own guitar, using scraps from previous instruments and cheap parts purchased from his buddies at Charvel.

Modifying a guitar with new or spare parts was a radical idea in the seventies, but it was easy to see where Ed got his inspiration. Southern California was the birthplace of hot-rod culture, where backyard car mechanics, working with junkyard parts, would compete with each other to see who could make the fastest car. His Pasadena hometown was a major center for these DIY mechanics, and custom cars were literally everywhere. Don Blair’s legendary Speed Shop, one of the first shops to sell custom parts in Southern California, was located less than two miles from where Ed grew up, and the town’s connection to “kustom kar kulture” was caricatured in Jan & Dean’s 1964 novelty hit “The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena),” about a granny with a fast car and a lead foot.

At the time, Charvel and Lynn Ellsworth were making replacement guitar bodies and necks and selling them under the Boogie Bodies brand. Van Halen dropped by the factory sometime in 1975 and bought an ash Strat body for $50. It was, he recalls, a “piece-of-shit” body on the bottom of a stack of other bodies. For another $80, he acquired an unfinished maple neck.

Because the body was pre-routed for three narrow, Fender-style pickups, Van Halen chiseled out a larger cavity to install a bigger standard humbucking pickup, nearest to the bridge. He pulled the humbucker from his Gibson ES-335 and mounted it to the new body—a move that enhanced the guitar’s bass response, liveliness, and sustain.

Though there were chambers for two more pickups, Van Halen left them empy; he couldn’t remember the wiring circuit for installing additional pickups and tone controls (“I never touched the tone controls anyway”). He also installed jumbo Gibson frets on the fretboard, and a brass nut on the neck of the guitar, and salvaged a vibrato tailpiece from one of his vintage Strat guitars to repurpose for this new, homegrown instrument.

To cover the empty pickup holes, he cut a piece of black vinyl and nailed it on, covering the cavity. The final and most distinctive touch was a black-and-white-striped finish. Van Halen applied this by first spraying the body with several coats of black acrylic lacquer paint, then taping it up and spraying several coats of white lacquer paint over it. The tape was removed once the final coat was dry. The result of these modifications was a guitar that combined Van Halen’s favorite aspects of his Les Paul Standard, his ES-335, and his Strat.

A Frankenstrat was born.

—

WHEN VAN HALEN’S self-titled debut album was released in 1978, you could almost hear the resounding thud in the guitar community as jaws hit the ground. Van Halen’s debut sounded unlike anything heard before, largely due to Ed’s guitar playing. While the opening track “Runnin’ with the Devil” offered a taste of his larger-than-life sound, it was the second track that started a revolution.

In a mere 1:42, the solo guitar instrumental “Eruption” changed the way electric guitarists looked at the instrument forever. As the title suggests, the track was an explosion of musical ideas—sounds and techniques that paved the road for guitarists for decades to come.

Using his Frankenstrat guitar, tuned down a half-step to E-flat, through a 1968 Marshall Super Lead tube amp, supplemented by an MXR Phase 90, a Univox echo unit, and the Sunset Sound studio reverb room, Edward offered a brief—but devastating—summary of everything he had been working on in the previous years.

First, there was the tone of his homemade guitar itself, which Van Halen referred to as his “brown sound.” He had always admired the rich, liquid textures of Eric Clapton during his Cream era, but Ed’s guitar added extra bite to the beauty. His sound was big, round, and majestic when needed, but it could also ring out with sharp clarity during quicker passages. His deft use of reverb and echo contributed to the concert hall vibe.

But what caused the real ruckus was the song’s ultra-speedy licks and Eddie’s use of two-handed tapping. Employed three decades earlier by Jimmie Webster on his Gretsch guitars, it was still a relatively unused technique wherein the guitarist engages fingers from both hands at once on the fretboard, in order to play intervals and passages that would be impossible using only the fretting hand.

“Tapping is like having a sixth finger on your left hand,” Van Halen explained at the time of the album’s release. “Instead of picking, you’re hitting a note on the fretboard. I was just sitting in my room at home, drinking a beer, and I remembered seeing other players using the technique for one quick note in a solo. I thought, ‘Well, nobody is really capitalizing on that idea.’ So I started dickin’ around and realized the potential. I had never seen anyone take it as far as I did.”

Young guitarists completely flipped for Ed’s sound, and even the most jaded members of the guitar community were impressed. Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, who rarely handed out compliments, said, “For my money, Van Halen is the first significant new kid on the block. Very dazzling. He flies the flag well.” Even the curmudgeonly Frank Zappa thanked Eddie for “reinventing the guitar.”

After the release of the first Van Halen album, the musical universe shifted. Being a guitar hero was suddenly more fashionable than it had been since the heyday of Hendrix and Clapton. But now the bar had been raised, and the stakes were greater. If you were really going to compete with King Edward, you’d better be fast as hell, look cool, have a trove of new ideas, and a guitar nobody had ever seen.

Influenced by the work of eighteenth-century violinist Niccolo Paganini, the fierce Swedish guitar sensation Lars Johan Yngve Lannerbäck, more commonly known as Yngwie Malmsteen, introduced classical scales and arpeggios to the rock world and pioneered the use of sweep picking, a technique in which the guitarist plays single notes on consecutive strings with a sweeping motion of the pick, to produce a lightning-fast series of notes.

The Swede, who often dressed like a flamboyant rock-and-roll Beethoven, preferred to play a traditional Fender Stratocaster, but he radically altered it by scalloping the fretboard, a modification that scoops out some of the wood between the frets and facilitated Malmsteen’s tremendous speed and wild vibrato.

A steady stream of shredders were to follow, many with their own signature instruments built to their specifications by up-and-coming guitar companies looking to knock Fender and Gibson off their pedestals. Steve Vai and Joe Satriani, two phenoms from Carle Place, New York, had colorful guitars crafted for them by the Japanese brand Ibanez, both featuring pickups custom-made by Larry DiMarzio. Mick Mars of Mötley Crüe played an angular B.C. Rich Warlock, while Dokken guitarist George Lynch had ESP, another Japanese company, build him an instrument with a “Kamikaze” graphic.

Not since the heyday of bebop in the fifties had so many fast and inventive musicians invaded the pop music market. Most of these flashy young guns played in “hair metal” bands, a hard rock subgenre known for its colorful clothes, androgynous style, crunchy riffs, pop choruses, and incredible guitar solos.

For all the competition, Van Halen would remain one step ahead for years to come. One of his most historically important performances came in 1982 when mega-producer Quincy Jones enlisted Ed to play a solo on Michael Jackson’s work in progress, Thriller. What eventually became “Beat It” exploded racial barriers on MTV and rock radio. It would contribute to Thriller’s claim to being the best-selling album of all time.

Van Halen recalls his role in the song’s birth:

I get this call and I said, “Hello?” And I hear a guy on the other end going “Hello? Hello?” We couldn’t hear each other, so I hung up. The phone rings again and I hear this voice on the other end asking: “Is this Eddie? It’s Quincy, man!” And I’m like, “Who the fuck? What do you want, you fuckin’ asshole?” So finally he says, “It’s Quincy Jones, man!” And I’m goin’, “Ohhh, shit! I’m sorry, man…” After the record, he wrote me a letter thanking me and signed it “The Fuckin’ Asshole.”

—

ED CONTINUED TO tinker with his Frankenstrat across the decades, making it into an even sexier, more formidable monster. In 1979 he had retaped the body of his black and white guitar and painted over it with red Schwinn bicycle paint, creating the guitar look most associated with Van Halen. Additionally, he gave his creation a little “trailer trash” flash by attaching red truck reflectors to the rear of the body and installing large eyehook screws to the horn and back of the guitar—a foolproof method of keeping his strap attached to his instrument.

In addition to revamping the cosmetics, Van Halen would help refine another major guitar innovation: the locking tremolo system. Using a whammy bar was a major part of his playing technique, allowing him to bend notes dramatically. But excessive use often caused his strings to fall hopelessly out of tune. He had developed a number of strategies to minimize the problem, but he was unable to come up with a solution that worked all the time.

Just as Ed’s star was rising, a guitarist named Floyd Rose was dealing with the same set of issues. Rose was playing in a rock band and wanted to use his whammy bar the way his hero Jimi Hendrix did, but was frustrated when his guitar wouldn’t stay in tune. Using skills acquired from years of jewelry making, he devised an ingenious system of clamps that would lock the strings of the guitar at the nut (where the neck meets the head) and again at the bridge. Together they’d keep the guitar in tune even under extreme duress.

Rose shared his invention with his friend Lynn Ellsworth, who immediately thought of Edward. “So, I went with him to show Eddie the locking system I created,” says Rose. “He liked it and gave me a guitar to put one on.”

Ed picks up the story from there: “My role in the design and development of the Floyd was adding the fine tuners to the bridge…Strings stretch, temperature changes, and depending on how hard you play, your guitar would go out of tune. So, you’d have to unclamp the nut, which involves loosening three screws with an Allen wrench, tune the guitar, and re-clamp the nut down again. There wasn’t enough time to do all this in between every song live…To put it simply, it was a pain in the ass.” So Eddie suggested adding fine tuners to the bridge. This would allow a player to lock down the strings, so they’d essentially stay in tune, but to still make subtle adjustments when needed. And it worked, becoming an essential device for rock players in the eighties and beyond.

It was no surprise that a number of guitar companies started knocking on Van Halen’s door. Who wouldn’t want to work with the man who had completely revolutionized their business? In the last few decades he has collaborated with Kramer, Music Man, and Peavey, before joining forces with a revived and rejuvenated Fender in 2005. Unlike guitarists who endorse products in name only, Eddie worked tirelessly with each brand he was associated with to improve and refine his ideas in an effort to build better products. One of his latest guitars, the EVH Wolfgang, took over three years to design, and during that time over eighty different pickups alone were tested before one was deemed good enough for the guitar.

When journalists ask Ed who his biggest influences are, he often confounds them by saying Les Paul. Anyone who knows guitar history understands exactly why Van Halen would cite the mighty Wizard from Waukesha. What other figures were equal parts virtuoso and technical innovator? Before Paul passed away in 2009, he and Van Halen had become extremely close friends. Ed often chuckled at the memories of Les calling him at 3:00 a.m. to discuss some esoteric guitar-related concept, or else to simply bullshit. During those late-night chats, Eddie recalls with pride, Les would often sign off by saying, “There’s only been three great electric guitar makers: me, you and Leo [Fender].”

In 2015, Ed promised there would be more new guitars to come. “I don’t know if there is such a thing as perfection,” the guitarist said, “but the Wolfgang is the best of everything we could find at this moment. I’m always changing, so even ‘the best’ is a tough word for me to define. I’m going to continue work on building better guitars.”

As for his beloved red, black, and white Frankenstrat guitar, Ed still uses it here and there. But lest anyone doubt its lasting significance, in 2011 the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., came knocking on Van Halen’s door asking to add the prized instrument to its collection. Eddie refused to part with the original, but recognizing the honor, offered up “Frank 2,” an exact duplicate made by a master guitar builder at Fender and used during Van Halen’s 2007-8 North American tour.

The museum’s director, Brent D. Glass, put it solemnly: “The museum collects objects that are multidimensional, and this guitar reflects innovation, talent and influence.” Ed would no doubt agree with that assessment, but in his earthy, self-deprecating way he would probably add that it also reflects “a whole lotta dickin’ around.”

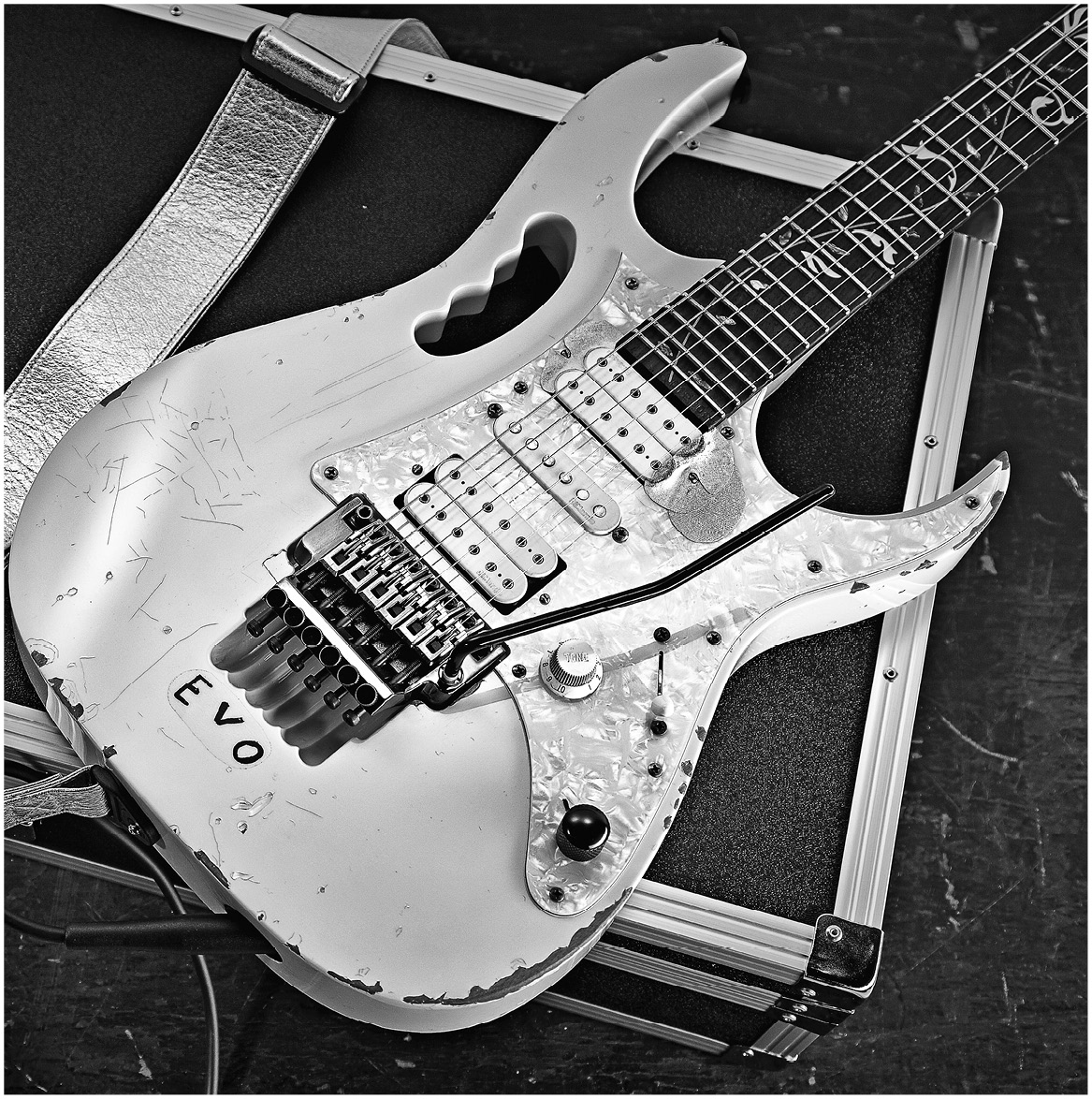

Steve Vai’s Ibanez white JEM7V-EVO, his primary stage and recording guitar