Bitterman's Craft Salt Cooking: The Single Ingredient That Transforms All Your Favorite Foods and Recipes - Mark Bitterman (2016)

INTRODUCTION. THE FOOD THAT TIME FORGOT

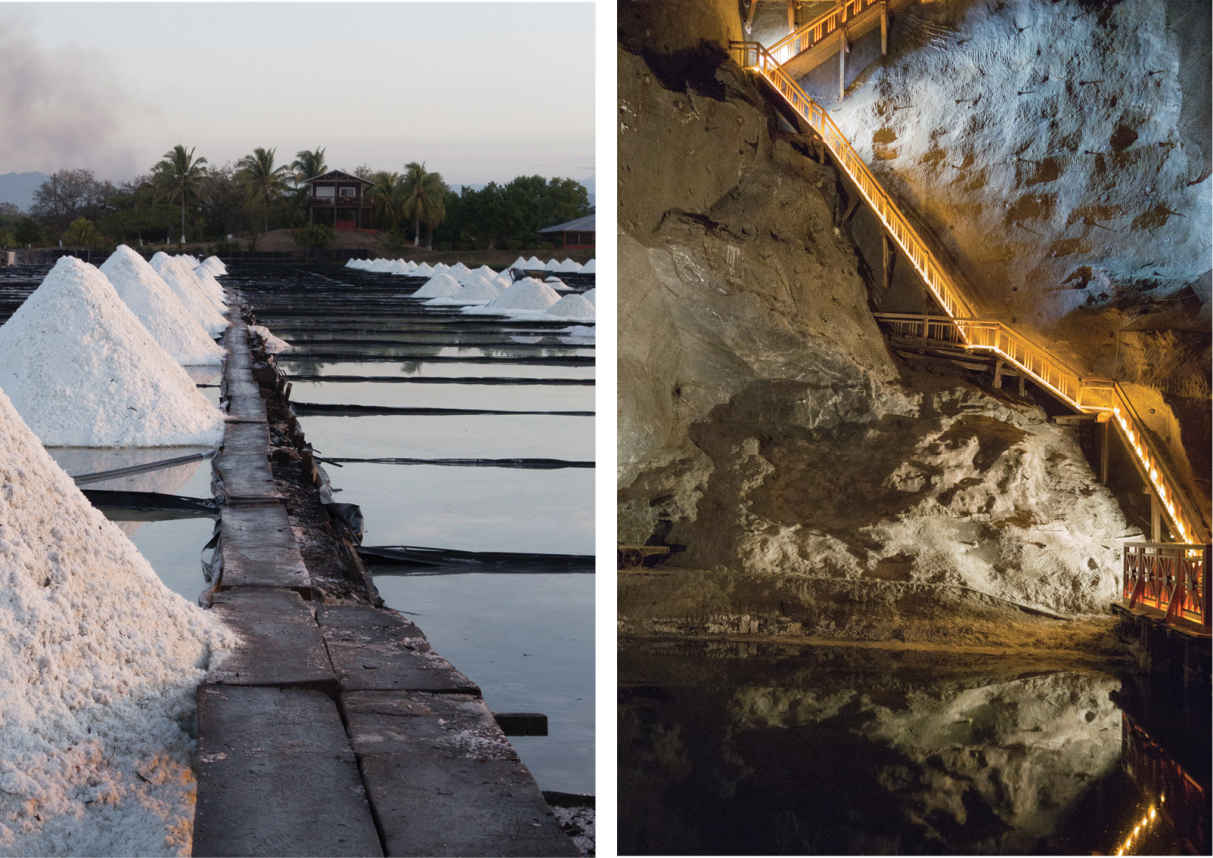

Iawake early, an hour before the sun came up, eager to explore the salt farm. The air is warm on my skin, humid but fresh. Barefoot, I take the narrow path through the marsh grasses toward the salt ponds, through the cordgrass, flowering salicornia, and sea lavender. Salt crystals crunch under my feet as I pick my way along the rough wooden planks that cross the ponds. I stop in the middle, and the still waters around me mirror the golden fire of dawn reaching up through a purple sky, silhouetting the scattered volcanoes to the east and along the border of El Salvador to the south. Behind me, to the west, birds squawk like pterodactyls from the shadows of the mangrove forest, and the faint roar of the ocean fills up the space beyond. I kneel, sift my fingers through the brine, and touch the glistening crystals to my lips. The flavor is unlike anything on earth; this is craft salt.

Salt is a food that traces its roots back to the horizon where mankind meets nature. Over the millennia, across virtually every culture and locale, everyone who could make salt did make salt. It was never easy. Water had to be evaporated using the sun or fire from seas or salt springs, or raw salt rocks had to be broken and pulled by brute force from the earth. Environments like salt marshes had to be protected, and resources like wood had to be conserved. It took great ingenuity and skill, honed over centuries to a fine craft, to achieve salt making that was reliable and sustainable. Salt is one of the most varied, locally rooted, ingeniously produced, and distinctive foods on earth.

Our planet is home to many hundreds of craft salts, each a perfect, authentic reflection of its native ecology, economy, and culinary tradition. But in order to use them, you don’t need access to every one. For practical use, there are only seven categories of salt, which all of the hundreds of varieties fall into: fleur de sel, sel gris, flake salt, traditional salt, shio, rock salt, and smoked/infused salt.

Each of the salts that make up these broad categories look and taste like no other salt on earth, from mild to bold, from briny to sweet, from dry to moist, from delicate to rugged, from tactfully unprepossessing to ostentatiously gregarious. A single respectful glance at craft salt reveals something truly amazing: Salt has personality. Each has stories to tell that give our purchasing dollars meaning and make our cooking fulfilling.

The mission of this book is to make you think differently about salt and empower you to make food that is better in every way—taste, texture, eye appeal, and nutrition. My aims are to share an appreciation for real, naturally made salt and to reveal how the lively personalities of distinctive craft salts will celebrate your food like nothing else. With a pluck of courage, we can unearth the lost truth of craft salt, reveal its ancient power, and explore new horizons of flavor and satisfaction in cooking.

WINNING SALT

There are two ways to make salt. The most common salts are made by a process called winning, meaning evaporating salt water from the ocean, salt springs or wells, or from manmade brine. The other way is to dig it up out of the earth from a salt deposit.

Sea salts are the most common type of evaporative salt. Making them is simple enough, on paper: Collect some seawater in a shallow pond, keep it out of the rain, let the sun evaporate all the water, and then collect what’s left. In reality it’s fantastically more complicated than that. The process has to be controlled to crystallize the minerals you do want and leave behind the ones you don’t. You need a lot of space dedicated to concentrating the seawater, and then a tidy, manageable area for crystallizing the salt and collecting it. If it rains, you’re done for, so you need to pick the right place, and then scale everything to perfection so that you can make a reasonable quantity of salt before losing everything. If a storm comes, you lose the whole harvest, or worse, the entire salt farm.

Modernization has thrown up its own challenges, including the threat to salt marshes of urban development and pollution of the oceans. Perhaps the most difficult challenge faced by traditional sea salt farmers is the advent of large-scale, mechanized salt farming. Challenges notwithstanding, skilled practitioners of traditional solar salt making can be found around the globe. From Guatemala mangrove forests to highland Bolivia salt flats; from the Philippines to Vietnam; across Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Slovenia; from India to Eritrea to Ghana and a dozen countries in between, solar salt making is a vital economic activity and a storied connection to the past. Salt springs also feed famed salt works from Spain to Peru to China.

Lacking either an arid climate or natural concentrated brines, people have to get inventive. Bringing seawater into greenhouses both heats the brine and surrounding air to accelerate evaporation and protects the slowly forming salt from rain. This method has taken off in recent years in the Americas, where an often inhospitable climate and an insistence on sustainability converge to push salt makers to innovate. Hawaii, Maine, South Carolina, Florida, West Virginia, British Columbia, and Newfoundland are homes to greenhouse or similar zero-emissions salt-making techniques.

Yet another way to make salt sustainably is to look in the opposite direction of the sun, which is to say, straight down. Salt makers from Iceland to Wyoming to China have harnessed natural geothermal energy to make salt. The Earth’s liquid mantle delivers more than twice the total of all humanity’s energy output to Earth’s crust, superheating water that can be tapped at hot springs to heat pans filled with saltwater, creating exquisite salts in very inclement climates.

FIRE-EVAPORATED SALT

What do you do if you want to make salt, but there is simply not enough sun, too much rain, or no other natural sources of heat? The simple answer would be to boil off seawater using wood or coal or oil. This method was once widespread. Entire forests in Europe were decimated. Entire regions of England were blighted by coal soot. Thirty pounds of raw seawater must be evaporated to make a single pound of salt. The next time you reach for a box of fire-evaporated salt, consider that fossil fuels are a big part of the price tag!

Today environmental concerns make relying exclusively on fossil fuels to do the job unappealing and impractical in most instances, but there are exceptions. Many of the best fire-evaporated salts start with naturally concentrated brines, such as from a salt spring, well, or marsh, or use the limited available sun and wind to pre-evaporate the seawater to concentrate it before boiling off the remainder to crystallize salt. After 100,000 years of exploitation by Neolithic and post-Neolithic people in France, Le Briquetage de la Seille was developed and run as a major industrial salt works, boiling salt spring brine in earthenware vessels, breaking open the vessels to remove the cake of salt, and then discarding the vessels in heaps, converting at least 200 acres of the once flat countryside into a land of sprawling hills. People in China’s Sichuan province have for millennia been pumping concentrated brine from 2,000-foot-deep wells in the earth. Neolithic England was home to salt making in its southern salt marshes—a practice that continues there today.

Where naturally concentrated brines are not available, ingenuity is required. The Japanese spray water onto bamboo mats suspended from the ceiling of a greenhouse, or drizzle water down long rods of bamboo, or even strew saltwater over seaweed or sand to allow it to quickly dry in the sun, then rinse the salt from the sand in seawater. A salt maker in Norway harnesses freezing weather rather than hot sun to concentrate saltwater. As seawater nears freezing, the water molecules crystallize, pushing the heavier saltwater to the bottom and yielding a concentrated brine that can then be evaporated by fire.

Some of the most desperate populations lack saltwater or salt deposits of any kind. In Paraguay, trees with a high salt content are burned, and the residual salt is rinsed from the ash and then boiled off. This same technique is practiced in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere, each locale burning its indigenous salty trees and grasses. One particularly innovative method, in the Philippines, involves soaking coconut husks in seawater for several months, drying and burning the coconut husks, washing the ash with saltwater to create a concentrated brine, and then boiling it off in a pot over a fire until nothing is left but a big round ball of salt. If you weren’t convinced that mankind will do anything to get salt, these methods are proof.

The upshot is that spectacular salts can be made using either solar, fire, or hybrid methods. Solar (and geothermal) salts tend to be less expensive and more environmentally sustainable. For these reasons, solar salts are generally the best candidates for everyday cooking salts. Rock salts are also worth considering for use as an all-purpose salt, though for reasons we shall explore below, they may not be the ideal choice for many people.

ROCK SALT

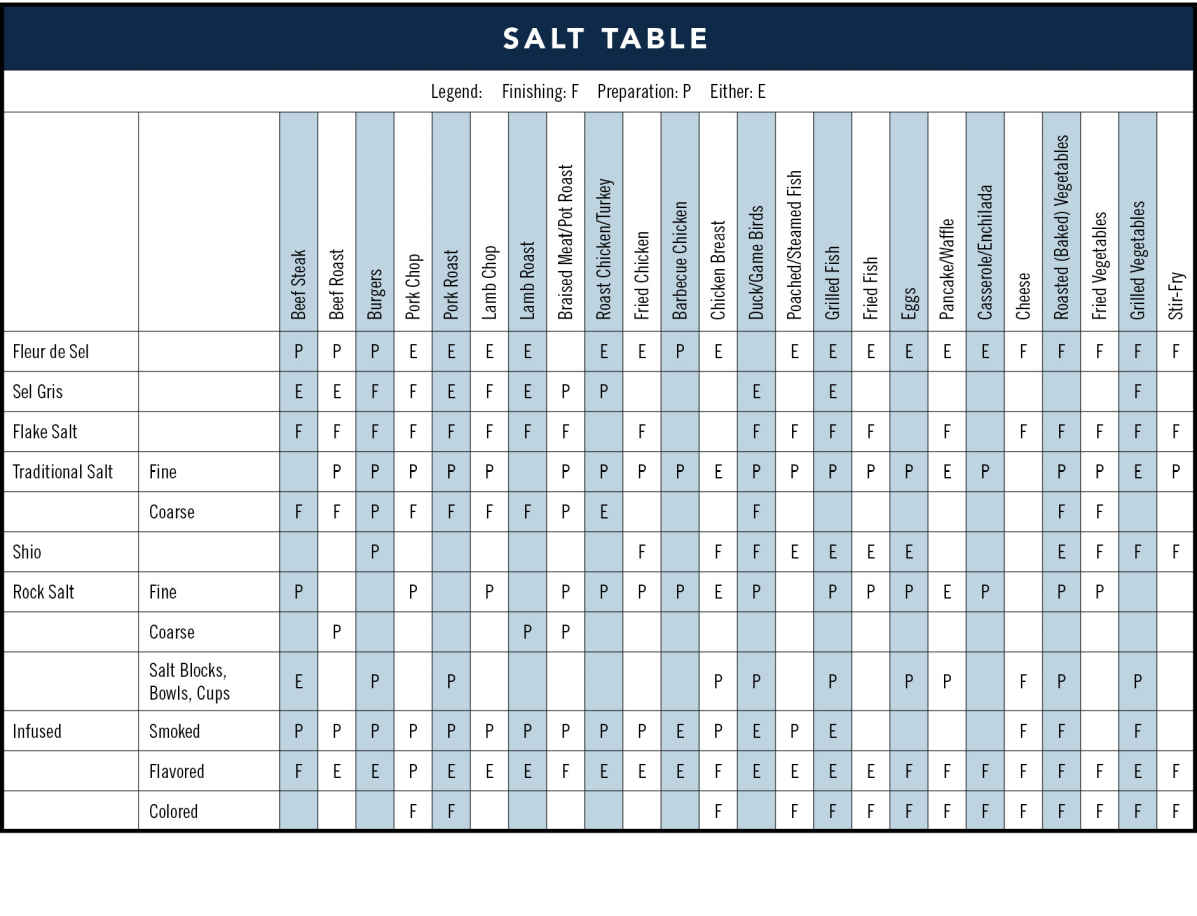

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates the earth contains 332,519,000 cubic miles of water, 97 percent of which is saline. Every square mile contains 120 million tons of salt. Millions of years ago, much of the earth that today is land was buried under this saltwater. On occasion these ancient seas would become isolated as landmasses arose around them or as sea levels dropped during ice ages, stranding inland seas. These seas evaporated, leaving vast salt deposits that would eventually get buried under sediments and other geological formations. Under the tremendous pressure of the earth above, salt deposits would solidify into solid rock called halite, the mineral form of salt. The earth contains countless such salt deposits.

The Hallein salt mine in present-day Austria shows evidence of salt being evaporated from salt springs dating 4,000 years before organized rock salt mining of rock salt began there, around 600 BC. Two of the most famous salt mines in the world are the Wieliczka mine in Poland, near Krakow, and the Khewra mine in Pakistan’s Punjab province. The Wieliczka mine (pronounced vee-LEE-ska) has been in operation since the 12th century. Intellectuals, dignitaries, and industrialists from around Europe have visited for centuries, and it is home to some of the most astonishing feats of minecraft anywhere. Caverns the size of small stadiums are buttressed by timbers stacked like Lincoln Logs. Animals were lowered down to the mine to work out their natural lives. Pulley systems, pump systems, stairways, elevators, tunnels, and halls weave throughout the byzantine maze of the mine. But here art rivals engineering for impressiveness. Miners, a religious and superstitious bunch, carved sculptures of everything from religious icons and personages to mythical dwarves, whom they believed contributed a helping hand, secretly working the mines at night. Mining of rock salt in Wieliczka recently ceased, but tourism continues.

The Khewra mine, in the Punjab region of Pakistan, is the largest of several in the region where so-called Himalayan salt comes from. The term Himalayan is a colorful one, as the mines are separated from the Himalayas by nearly 200 miles. The mines have been used since their discovery in 326 BC, and there is evidence to suggest that salt was being mined prior to that. Deep in its nearly 25 miles of tunnels winding through 43 square miles over seventeen levels, miners have carved elaborate structures and sculptures. Among them is a 350-foot-tall assembly hall with 300 narrow stairs of salt; a 3,000-square-foot mosque that was constructed over the course of half a century; and a salt bridge known as the Pull Sarat, or bridge of trial. It is 25 feet long, with no supporting pillars, spanning a subterranean saline pond. Other items include miniature versions of the Great Wall of China; the Eiffel Tower; and two Pakistani landmarks, Chaghi Mountain and Lahore’s Minar-e-Pakistan. Khewra produces 300,000 tons per year. A good-size industrial salt mine might produce ten times that amount or more.

CRAFT VS. INDUSTRY: THE MODERN HISTORY OF SALT

The idea of good salt versus bad salt is not a new one. In the 1800s, the salt of choice was cheap, industrially made salt from Liverpool. Salt makers there boiled off brine using enormous amounts of cheap coal and other fossil fuels. Besides being an environmental catastrophe, the process yielded salt that many believed to be of middling quality at best. A letter circulated by the U.S. Senate in 1932 lambasted “the violent boiling and hasty crystallization” of “Liverpool salt, whose fair and tempting exterior renders it peculiarly imposing, whilst its intrinsic deficiency makes the delusional most pernicious and ruinous… . Indeed, this artificial salt is exceedingly unlike the salt formed by the evaporation and crystallization, which sea water naturally undergoes in the warmer latitudes.” The letter continued on, lamenting its ruinous effect on beef, pork, and New York butter, among other foods. Such recognition is largely absent from discussions on salt today, but we are still besieged by inexpensive, inferior salt. Today it wallows in our food supply in the form of cheap sea salt, iodized table salt, and kosher salt.

KOSHER SALT AIN’T KOSHER

Kosher salt has been a longtime favorite in restaurants in the United States, and from there it became the darling of food magazines and many cookbook authors as well. What is strange is that kosher salt is an industrially compromised ingredient. Most serious cooks eschew heavily processed foods (bologna, corn syrup, Cheez Whiz) or artificial chemicals (red dye #5, vanillin, MSG) in their cooking. Kosher salt is both of those things. It is made by pumping water into a salt deposit, chemically refining the resulting brine, and then boiling it off in large factories using series vacuum evaporators fired by fossil fuels.

Another common rationale for using kosher salt is that it’s cheap and readily available. This is true, but how much more expensive is it to use the best natural salt? A serving of superb natural salt costs about 3 cents, about the cost of a single slice of cucumber. Regardless of the cost, does “cheap and ubiquitous” express your aspirations as a cook? Excellent handcrafted salt is a luxury everyone deserves and can afford. Use salt that matters.

A WORD ON IODINE

Normally we get all the iodine we need from food, most notably seafood and dairy, but also beans, meat, and eggs. Sea vegetables, like seaweed salads, chips, or sheets, are so naturally high in iodine that they should actually be eaten in moderation. Salt is not, and never has been, a natural source of iodine.

Widespread access to seafood, dairy, and other iodine-rich foods has greatly reduced our need for iodine supplements. The British Dietetic Association states: “Most adults following a healthy, balanced diet that contains milk, dairy products, and fish should be able to meet their iodine requirements. A supplement containing iodine can help meet your iodine needs if you do not consume sufficient iodine-rich foods.” Multivitamins and natural supplements at health food stores are convenient sources.

Where you should not be getting your iodine is from your salt. Relying on foods with additives for proper nutrition is deeply problematic. If we turn to cupcakes made with fortified flour for our vitamin B12, we are getting lots of things we don’t need just to get a little of what we do need. The harsh, faintly acrid flavor of iodized salt should warn you off it.

A SEA SALT IS NOT A SEA SALT

Sea salt is a tricky one. What most people think when they say “sea salt” is something natural, pristine, and beautiful as the sea itself. What they are getting is another story altogether. Most generic sea salt is made on mega-farms like Exportadora de Sal in Baja California, which cranks out about 7 million tons a year, or Morton’s Inagua salt fields in the Bahamas, which produce about 2 million tons a year. Cargill owns the largest sea salt operation in the United States, admired for its striking salt fields seen in the San Francisco Bay on approach to San Francisco International Airport. All of these makers share one goal: to make vast amounts of pure refined NaCl. These industrial sea salts are marketed as wholesome products made in harmony with nature, but in truth they rely on vast evaporating ponds that can undermine the sensitive ecological balance of their surroundings, and they require the use of heavy machinery, with all their attendant pollution. And the proof is in the pudding: At 99.8 percent pure NaCl, bereft of any of salt’s natural minerals, this salt is more refined than any food it seasons.

FOOD VS. CHEMICAL

Salt has been made to season food, preserve food, and supplement the diet of humans and livestock for thousands of years. About 270 million tons of salt are made every year—around 740,000 tons every day. However, salt for food and food processing makes up just 4 percent of the market, small potatoes next to the industrial uses for it.

In the mid-1800s salt found a new market, one that dwarfed its use in food. In the 1860s, Ernest Solvay perfected a method for making sodium carbonate (soda ash) by bubbling carbon dioxide through ammonia-containing salt brines. Today the world manufactures in the neighborhood of 50 million tons (45 million metric tons) of sodium carbonate, and its innumerable uses include dozens of chemical processes, water treatment, and making everything from detergents to paper to glass. The 1800s also saw the development of the chloralkali process for making chlorine and sodium hydroxide (caustic soda) from salt. Global chloralkali production is a staggering 200 million tons per year and growing. Gas exploration, pulp and paper making, metal processing, textile making and dyeing, tanning and leather treatment, rubber manufacture, and other industrial applications are the major uses. Road de-icing makes up yet another mega-market for salt, particularly in the United States.

THE CRAFT SALT FAMILY

We have been taught since childhood to think that salt is simple, but nothing could be further from the truth. Every craft salt has its own personality, and every personality is eager for an opportunity to harmonize (or clash) with your food. Rather than wade through an endless sea of different voices, we can combine them all into seven families: fleur de sel, sel gris, flake, traditional, shio, rock, and smoked and infused.

1. FLEUR DE SEL has delicate, moist, granular crystals and full mineral flavor. Fleur de sel forms when the weather is warm, and perhaps a light breeze tousles the surface waters of the crystallizing pan. Out of nowhere, salt crystals bloom across its face. In accommodating climates, fleur de sel crystals may sink and rest below the surface briefly, and then they are harvested before they have a chance to grow larger. The most important thing about fleur de sel is that the crystals are naturally fine, each as delicate and unique as a snowflake. Use it on milder, medium-bodied foods—everything from buttered toast to cooked vegetables to fish and pork.

2. SEL GRIS (also called bay salt or gray salt) boasts coarse, granular crystals with lots of moisture and rich, mineral flavor. Sel gris crystals form on the surface of a salt brine and also within the brine, and collect on the bottom. Sel gris is then raked off before it grows into a solid layer of salt, usually every several days. French sel gris is silvery gray from the trace amounts of silicates collected from the salt pan. Elsewhere, salt pans may be lined with a barrier against the mud below, or salt makers may allow a layer of salt to form on the bottom of the pan and then rake crystals off that layer. This produces very white salt that is nonetheless a sel gris. This is your salt for steak, lamb, root vegetables, and roasts of every kind.

3. FLAKE SALT comes in parchment-fine flecks and beautiful geometric pyramids. Flake salts are about fragility. The finest flake salts are so brittle that they pop into a million pieces if you so much as look at them the wrong way. Because they have very little mass for all that surface area, each crunch communicates only a smidge of salt. Some are moist; others are very dry. Though flake salts are most commonly made by evaporating water at a rapid rate, often at a boil, with fire or some other external heat source, there are a handful of flake salts made using only solar energy, usually in greenhouses. Flakes are incredibly variable from one maker to another, from one technique to another. Some form in tall, hollow pyramids, pointy as arrowheads, while others are squat pyramids, flat as Chinese throwing stars, and others are infinitesimally fine, like frost on the edge of a windowpane. Use them on fresh greens, cocktail rims, or anywhere a crisp, fleeting salt sensation is desired.

4. TRADITIONAL SALT (also referred to generically as sea salt and sometimes also bay salt) can be coarse or fine grained. Traditional salts are made similarly to fleur de sel and sel gris, except that rather than harvesting every day or several days, the salt is allowed to accumulate for months or even years. It is then harvested in huge chunks from a thick layer of salt accumulated on the bottom of a salt pan. The chunks are then mechanically ground down to the desired fineness. The salts can be made following any number of methods, from fire to geothermal to solar evaporation, though solar is by far the most common. Their use depends on the variety in question. Fine salts can be used as all-purpose cooking salts. Coarse salts can be used as a rustic touch on hearty foods.

5. SHIO is distinguished by fine to superfine grains. Named after the Japanese word for salt, shios are typically made in damp or cold climates where simple solar evaporation is not possible. Instead, salt water is pre-evaporated before being boiled or simmered into a concentrated brine over a fire; then the crystals are skimmed off the top or from within the brine. In short, it is made in much the same way as the best flake salts, except the crystals form in fine grains. Use shio on fish, steamed vegetables, in delicate broths, and—my favorite—in pickles.

6. ROCK SALT has hard, pebble-like crystals that can be ground to any coarseness. While many people consider rock salt to be the ultimate in natural, unrefined salts, in reality it is no more or less pure than any good sea salt, and it is lower in minerals than many and has harder, less sensuous crystals than most. Rock salt is made by mechanically grinding rocks and boulders of salt found in the earth and running the results through screens to sift out the desired crystal size. Rock salts, when finely ground, have excellent adhesion on fried foods like potato chips and french fries.

7. SMOKED AND INFUSED SALTS can be made with virtually any salt, though flake salts and medium-ground to finely ground traditional salts are the most common. Smoked salts are made by cold-smoking wet salt crystals so they take up the rich, natural aroma of smoking woods. Mesquite, hickory, apple, alder, cherry—any aromatic wood can be used to smoke salt. Sprinkle them on food as a finishing touch to lend rich outdoorsy flavor. Infused salts are made in a variety of ways, but regardless of the technique, the best ones achieve something better than the sum of their parts. Like smoked salts, the best results are achieved by using them as a finishing touch. Smoked and infused salts are for sprinkling wherever intense, high-fidelity flavor is desired.

ANATOMY OF SALT

Four characteristics come into play when salt is used to cook and finish foods: crystal structure, moisture content, mineral content, and place of origin.

CRYSTAL STRUCTURE is the most important feature of any salt. Crystals can be chunky and coarse or granular and fine; they can be smooth and solid or intensely fractured; they can form into huge pyramidal structures that splinter into flakes or into superfine fronds and flecks that threaten to dissolve almost instantly. The importance of crystal structure cannot be overstated. Undissolved, it dictates the impact of the salt on your palate: the pop, crackle, snap that lend tantalizing crunch on a steak, crispy freshness on vegetables, or simmering subtlety on seafood.

MOISTURE CONTENT lends mouthfeel to salt crystals. Dried-out salt is hard. Moist salt is unctuous. A coarse, chunky salt with plenty of moisture yields to your tooth for a satisfying suppleness. Moist salts will loll about on the tongue, generating and mixing with your saliva, while dry salts will soak up every available drop of moisture in your mouth. The first sensation is nice. The second, often as not, is not. Moisture also lends resiliency to salt, so if you want a salt to resist dissolving on food long enough to make it into your mouth intact, moisture is key. Flake salts are the exception, as the big crystals of some flake salts perch on food without dissolving, then burst in your mouth without parching it.

MINERAL CONTENT varies enormously from salt to salt, from 3 percent to as much as 30 percent trace minerals. Where crystal structure and moisture contribute to the impact of the salt, minerals are what give salt its flavor. Every sea, every salt spring has its own unique mineral fingerprint. Distinct from the impact of the salt, this mineral profile imparts the salt’s flavor. I call it “meroir”—akin to the terroir of wines. Some craft salts are briny, others are earthy; some are refined, others are harsh; some are sweet, others are bitter; and some are hot. Most are a combination of all of these sensations and more.

PLACE OF ORIGIN is a fourth consideration. While it does not directly affect your taste buds, it definitely affects the pleasure you take from your food. Place reflects our values. Place is a choice between farms or factories, sustainability or exploitation. And of course, places carry with them the thrill and romance of the flavors they evoke. A tagine redolent of Moroccan spices awakens an unconscious thrill of a North African moon rising over the Sahara. For me, fried garlic, steaming clams, and chopped parsley bring me back to a warm home for a linguine dinner with Mom. Salt is intimately connected to place, to natural environment, histories, and cuisines. The unique saltwater from which a salt is made, the unique climates that shape salts, and of course the unique people who do the salt making all resonate within every grain. Salt is about connection.

THE INGREDIENT VS. THE COOK

Throughout history, cuisine has witnessed a power struggle between ingredient and technique. Love of ingredient shows us how to respect and honor the origin, people, and virtue of food. Expertise with technique shows us how to optimize, transform, and create as cooks. The silent integrity of the ingredient demands considered techniques to celebrate it. Think of the ingredient as the inspiration, and the technique as the creation. You can’t have one without the other. When ingredients lack integrity, the creation lacks authenticity. Using cheap, poor-quality, industrialized ingredients will always make your food suffer. But using high-quality ingredients alone is not enough. To prepare truly delicious food, as opposed to the merely fashionable, surprising, or chic food, both technique and ingredient must shine, with neither outshining its partner.

“What do I want from my food?” That’s the question you should ask every time you cook. Because salt enhances the flavor of almost any ingredient, anyone who eats on a regular basis eventually starts to salt by rote. Consider the interaction of your ingredients with the techniques you will use to prepare them. Think of salting as an opportunity. Do you want it to spark and vanish or persist and penetrate? Do you want to build a crescendo of flavor or do you prefer salt to barely underscore the flavors that are already present? What textures do you want: a quick snap, a subtle crackle, a just perceptible crunch, or nothing at all?

Consider that all food is not created equal. Even when cooking ingredients from the same food group, variations in cooking methods can yield vastly different dishes. The stewed flavors of a long-braised brisket are not the same as those of a grilled rare steak. Why salt them the same? Pasta sauced with foraged morels is nothing like the same noodle glistening with jewels of raw ripe tomato under a sheen of fruity olive oil. We need to recognize those differences and honor them with the considered application of distinctive salts. Salting purposefully deepens your connection to your ingredients, allowing you to cook them more considerately and creatively.

Making the most of every opportunity to use finishing salt is a matter of understanding the behaviors of different types of salts and then picking a salt that you think will fulfill the mission you set for it. For example, finish with a fleur de sel when you want delicacy and balance in every bite, or a flake salt when you want sparkle and contrast. Finish with sel gris when you want a powerful intonation that endures well after the fork has left your mouth, or finish with a smoked salt when you want the natural aromas of cooking outdoors to greet you before you’ve taken your first bite.

The importance of finishing with salt does not mean you shouldn’t cook with it. A handful of traditional sea salt thrown into pasta water does wonders, and a sprinkling of fleur de sel an hour before grilling is the smartest thing you can do to up the ante on a thick steak. Stocks develop more flavor with salt. Vegetables brighten with salt in the water. Cookies may love salt sprinkled on top, but they need it in the dough, too.

THE THREE RULES OF SALTING

1. Cook with unsalted, whole foods whenever possible. Put yourself in the driver’s seat so that you can do the salting, not some food chemist. Let your mouth decide when, where, and how much to salt. Salted butter is meh. Unsalted butter with fleur de sel is miraculous.

2. Use craft salt, and only craft salt, every day. It will cost you a few pennies more per person, but you’ll be cooking like a king. Throw away your kosher salt, iodized table salt, and cheap sea salt. Salt brings pleasure. Your love is worth good salt.

3. Skew your salting toward the end of preparation, and use finishing salts. Use less or no salt while cooking, leaving room at the end to sprinkle a finishing salt of choice. Salt is the most powerful, distinctive ingredient. The right salt at the right time will celebrate your food like nothing else.

SALARIUS MAXIMUS

The purpose of salt is to elevate flavor and honor food. The best possible measure of a perfectly salted dish is not that it tastes salty, but that it tastes wonderfully, ecstatically like itself—or even better, like the dreamed-of ideal of itself. Salt makes pink fish taste like salmon, white roots taste like potato chips, and sweet dough taste like cookies. Sometimes, with outright aggressive salting, food can become something else altogether: an over-the-top, maddening sensation. A few recipes in this book tread the outer limits of sane salting, like the Fleur de Hell Fried Chicken, which employs a fine salt in the brine to moisten the meat and send the bird’s savory flavors through the roof, a coarse salt in the breading for a glittering mineral zing, and a flake salt to finish just for the electrostatic crunch of it.

Wowing as recipes like this can be, I’m not suggesting you make extreme salting a thematic part of your cooking. Adding too much salt can be like blasting the car radio to the point where the windows rattle as you drive down the street. The intensity of the experience drowns out the music. Remember, it’s moderation we are seeking, though even moderation needs to be practiced in moderation.

My first book, Salted: A Manifesto on the World’s Most Essential Mineral, with Recipes, is a celebration of salt, and the aim is to explore the untapped powers of the world’s many distinctive varieties. Because nothing shows salt off like whole salt crystals atop a finished dish, techniques in the book were skewed toward finishing with salt rather than cooking with it. In this book I pick up where Saltedleaves off, enlisting craft salt in a sweeping variety of salting techniques. As you work your way through the recipes here, I hope you will take note of the way we employ various techniques to push the boundaries of salting. Salt is frequently called upon several times in a recipe. You can blend a fine smoked salt with a chunky sel gris before rubbing it on a steak or chop like in the Thrice-Salted Rib-Eye Steaks. At other times, salting is a lesson in simplicity, like the Tossed Red Salad with Shallot Vinaigrette and Flake Salt. Show off some graphic panache with black and white salts atop Avocado Toast. For dessert, invite your mouth to a debate: White Chocolate Bark with Dark Chocolate Salt.

Like all chefs and many practiced home cooks, I add salt by pinches, not with measuring spoons, but in these recipes I have listed measurements of salt by teaspoon and tablespoon—not because I necessarily expect you to use them, but because it is the most accurate way of guiding you as you learn to salt purposefully. Once you get the hang of it, I encourage you to go pro and stop wasting time digging for spoon measures. Your fingers will give you vital data about the salts you’re using: their heft, their crunch, their moistness. As soon as you can, toss your measuring spoons out the window, but be cognizant of the risks. There is no way to rescue a dish once it has been oversalted. When you play with salt in your cooking, always be mindful of the total amount in any given recipe. Salting, like so much in life, is about judgment, but to live it to its fullest, it takes a little risk-taking.

WHERE IS YOUR SALT?

If we took out all the salt put into food by factories and chefs, our salt consumption would shift radically; 75 percent of the salt we eat comes from processed or prepared foods. Only 10 percent of our dietary salt comes naturally in the foods we eat (and far less if you are a vegetarian), and typically only 15 percent from salt we add ourselves. The salient story here is eat processed and prepared foods less, cook whole foods yourself, then let fly with the salt, adding it judiciously but generously, freeing yourself to bring every bite to the peak of perfection.

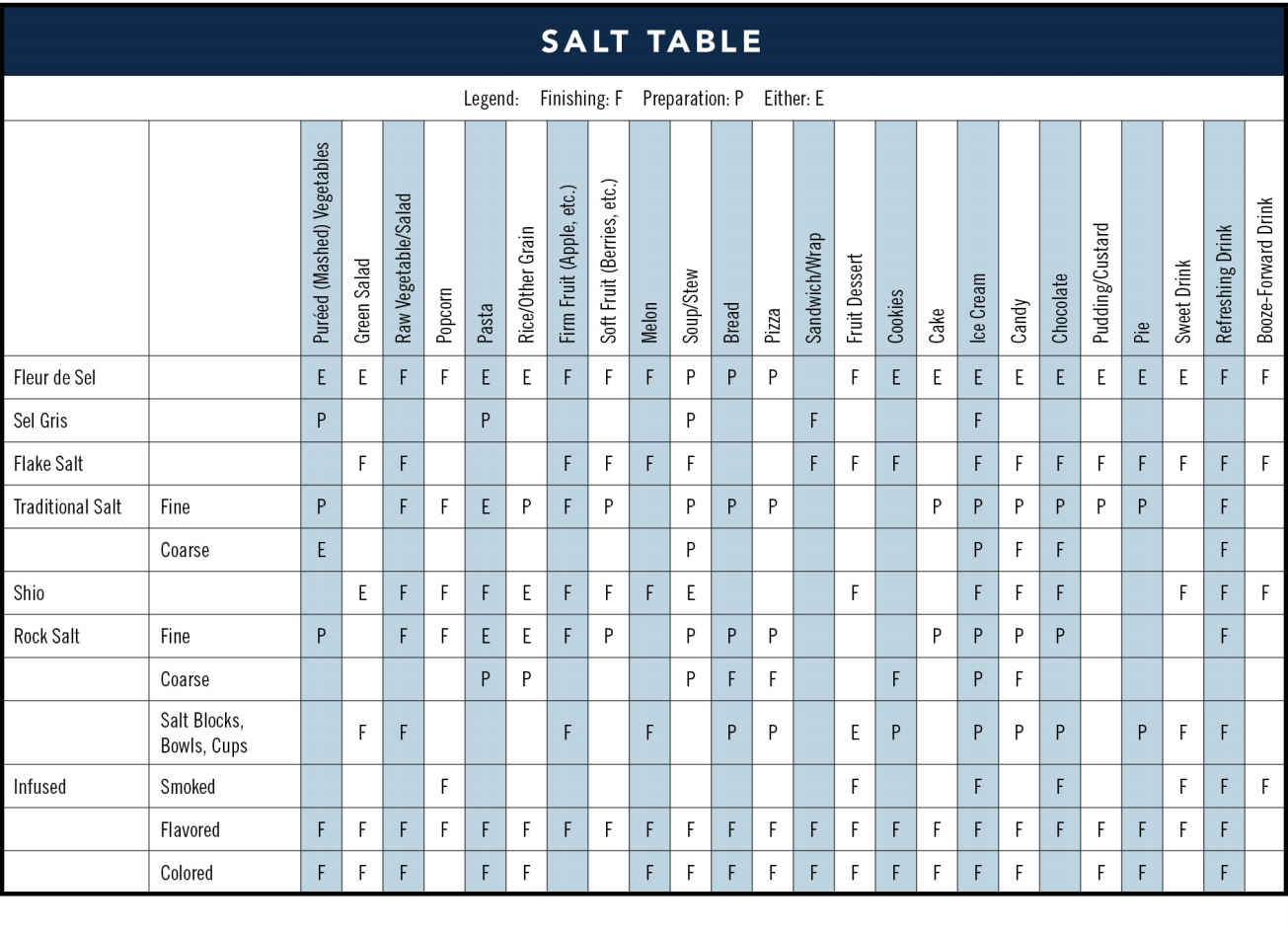

CHARTING SALT

Before the recipes in each section you will find a quick reference table listing food compatibilities for each of the seven salt families, and a Salt Box follows almost every recipe, giving you alternatives to the salts found in the ingredient lists. A Craft Salt Field Guide, organized by salt types, includes information about the individual types of salts found in this book.

FLEUR DE SEL

Delicately crunchy, fine grained for everyday cooking and sprinkling.

SEL GRIS

Coarse crystals with bold crunch and minerally flavor for hearty foods.

FLAKE SALT

Pyramidal confetti for snap and sparkle on fresh foods and cocktails.

TRADITIONAL SALT

Diverse family of salts made by hand in a time-honored fashion.

SHIO SALT

Fine, granular crystals harboring immense mineral richness.

ROCK SALT

Free-flowing crystals for baking, grinding, and shaking.

SMOKED SALT

Cold-smoked sea salt crystals for outdoorsy flavor and aroma.

INFUSED SALT

Select sea salt married with herbs and spices for an aromatic twist.