White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (2016)

Part I

TO BEGIN THE WORLD ANEW

CHAPTER FIVE

Andrew Jackson’s Cracker Country

The Squatter as Common Man

Obsquatulate, To mosey, or to abscond.

—“Cracker Dictionary,” Salem Gazette (1830)

By 1800, one-fifth of the American population had resettled on its “frontier,” the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi. Effective regulation of this mass migration was well beyond the limited powers of the federal government. Even so, officials understood that the country’s future depended on controlling this vast territory. Financial matters were involved too. Government sale of these lands was needed to reduce the nation’s war debts. Besides, the lands were hardly empty, and the potential for violent conflicts with Native Americans was ever present, as white migrants settled on lands they did not own. National greatness depended as much as anything upon the class of settlers that was advancing into the new territories. Would the West be a dumping ground for a refuse population? Or would the United States profit from its natural bounty and grow as a continental empire more equitably? There was much uncertainty.1

The western territories were for all intents and purposes America’s colonies. Despite the celebratory spirit in evidence each Fourth of July beginning in 1777, many anxieties left over from the period of the English colonization revived. Patriotic rhetoric aside, it was not at all clear that national independence had genuinely ennobled ordinary citizens. Economic prosperity had actually declined for most Americans in the wake of the Revolution. Those untethered from the land, who formed the ever- expanding population of landless squatters heading into the trans-Appalachian West, unleashed mixed feelings. To many minds, the migrant poor represented the United States’ re-creation of Britain’s most despised and impoverished class: vagrants. During the Revolution, under the Articles of Confederation (the first founding document before the Constitution was adopted), Congress drew a sharp line between those entitled to the privileges of citizenship and the “paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice” who stood outside the national community.2

The image of the typical poor white resident of the frontier was pathetic and striking to observers, but it wasn’t new at all. He was an updated version of William Byrd’s lazy lubber. He was the English vagrant wandering the countryside. If anything about him was new, it was that some observers granted him a folksy appeal: though coarse and ragged in his dress and manners, the post-Revolutionary backwoodsman was at times described as hospitable and generous, someone who invited weary travelers into his humble cabin. Yet his more favorable cast rarely lasted after the woods were cut down and settled towns and farms appeared. As civilization approached, the backwoodsman was expected to lay down roots, purchase land, and adjust his savage ways to polite society—or move on.

Whereas Franklin, Paine, and Jefferson envisioned Americans as a commercial people suited to a grand continent, those who wrote about the American breed during the nineteenth century conceived a different frontier character. This new generation of social commentators paid particular attention to a peculiar class of people living in the thickly forested Northwest Territory (Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin), along the marshy shores of the Mississippi, and amid the mountainous terrain and sandy barrens of the southern backcountry (western Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, plus the new states of Kentucky and Tennessee, and northern Alabama), and later the Florida, Arkansas, and Missouri Territories. In the heyday of James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), who gave early America the fearless forest guide known as Leatherstocking, the abstract cartography of the Enlightenment yielded to the local color of the novelist in describing the odd quirks of the rustic personality. Americans were starting to develop a mythic identity for themselves. The reading public was more attuned to travelers’ accounts than they were to grid plans and demographic numbers. As Americans looked west, and many moved farther away from cities and plantations along the East Coast, they discovered a sparsely settled wasteland. In place of Jefferson’s sturdy yeoman on his cultivated fields, they found the ragged squatter in his log cabin.3

The presumptive “new man” of the squatter’s frontier embodied the best and the worst of the American character. The “Adam” of the American wilderness had a split personality: he was half hearty rustic and half dirk-carrying highwayman. In his most favorable cast as backwoodsman, he was a homespun philosopher, an independent spirit, and a strong and courageous man who shunned fame and wealth. But turn him over and he became the white savage, a ruthless brawler and eye-gouger. This unwholesome type lived a brute existence in a dingy log cabin, with yelping dogs at his heels, a haggard wife, and a mongrel brood of brown and yellow brats to complete the sorry scene.

Early republican America had become a “cracker” country. City life catered to a minority of the population, as the rural majority fanned outward to the edges of civilization. While the British had made an attempt to prohibit western migration through the Proclamation of 1763, the Revolutionary War removed such barriers and acquiesced to the flood of poorer migrants. Both crackers and squatters—two terms that became shorthand for landless migrants—supposedly stayed just one step ahead of the “real” farmers, Jefferson’s idealized, commercially oriented cultivators. They lived off the grid, rarely attended a school or joined a church, and remained a potent symbol of poverty. To be lower class in rural America was to be one of the landless. They disappeared into unsettled territory and squatted down (occupied tracts without possessing a land title) anywhere and everywhere. If land-based analogies were still needed, they were not to be divided into grades of soil, as Jefferson had creatively conceived, but spread about as scrub foliage or, in bestial terms, mangy varmints infesting the land.4

The plight of the squatter was defined by his static nature and transient existence. With no guarantee of social mobility, the only gift he received from his country was the liberty to keep moving. Kris Kristofferson’s classic lyric resonates here: when it came to the cracker or squatter, freedom was just another word for nothing left to lose.

Both “squatter” and “cracker” were Americanisms, terms that updated inherited English notions of idleness and vagrancy. “Squatter,” in one 1815 dictionary, was a “cant name” among New Englanders for a person who illegally occupied land he did not own. An early usage of the word occurred in a letter of 1788 from Federalist Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts, writing to James Madison about his state’s ratifying convention. Identifying three classes of men opposed to the new federal Constitution, he listed the former supporters of Shays’ Rebellion in the western counties, the undecided who might be led astray by opinionated others, and the constituents of Maine: this last group were “squatters” who “lived upon other people’s land” and were “afraid of being brought to account.” Not yet a separate state, Maine was the wooded backcountry of Massachusetts, and Gorham was about to become one of the most powerful speculators in the unsettled lands of western New York State. In 1790, “squatter” appeared in a Pennsylvania newspaper, but written as “squatlers,” describing men who inhabited the western borderlands of that state, along the Susquehanna River. They were men who “sit down on river bottoms,” pretend to have titles, and chase off anyone who dares to usurp their claims.5

Interlopers and trespassers, unpoliced squatters and crackers grew crops, cut timber, hunted and fished on land they did not own. They lived in temporary huts beyond the reach of the civilizing forces of law and society and often in close proximity to Native Americans. In Massachusetts and Maine, squatters felt they had a right to the land (or should be paid) if they made improvements, that is, if they cleared away the trees, built fences, homes, and barns, and cultivated the soil. Their de facto claims were routinely challenged; families were chased off, their homes burned. Squatters often refused to leave, took up arms, and retaliated: a Pennsylvania man in 1807 shot a sheriff who tried to eject him. Down Easter Daniel Hildreth, tried and convicted of attempted murder in 1800, went after the proprietor himself.6

Slang tends to enter the vocabulary well after the condition it describes has existed. And so the presence of squatters predated the word itself. In Pennsylvania, as early as the 1740s, colonial officials issued stern proclamations to warn off illegitimate residents who were settling on the western lands of wealthy proprietors. Twenty years later, with little success in curbing their invasion, courts made the more egregious forms of trespass a capital crime. Yet even the threat of the gallows did not stop the flow of migrants across the Susquehanna, down the Ohio, and as far south as North Carolina and Georgia.7

British military officers were the first to record their impressions of this irrepressible class of humanity. As early as the 1750s, they were called the “scum of nature” and “vermin”; they had no means of support except theft and license. The military condemned them, but also used them. The motley caravan of settlers that gathered around encampments such as Fort Pitt (the future Pittsburgh), at the forks of the Ohio, Allegheny, and Monongahela Rivers, served as a buffer zone between the established colonial settlements along the Atlantic and Native tribes of the interior. A semicriminal class of men, whose women were dismissed as harlots by the soldiers, they trailed in the army’s wake as camp followers, sometimes in the guise of traders, other times as whole families.8

Colonial commanders such as Swiss-born colonel Henry Bouquet in Pennsylvania treated them all as expendable troublemakers, but occasionally employed them in attacking and killing so-called savages. Like the vagrants rounded up in England to fight foreign wars, these colonial outcasts had no lasting social value. In 1759, Bouquet argued that the only hope for improving the colonial frontier was through regular pruning. For him, war was a positive good when it killed off the vermin and weeded out the rubbish. They were “no better than savages,” he wrote, “their children brought up in the Woods like brutes, without any notion of Religion, [or] Government.” Nothing man could devise “improved the breed.”9

“Squatter” or “squat” carried a range of disreputable meanings. The term suggested squashing, flattening out, or beating down; it conjured images of scattering, spinning outward, spilling people across the land. Those who recurred to the term revived the older, vulgar slur of human waste, as in “squattering a soft turd.” By the late eighteenth century, in the time of the influential Buffon, squatting was uniformly associated with lesser peoples, such as the Hottentots, who reportedly convened their political meetings while squatting on the ground. During the Seven Years’ War, British forces used the tactic of squatting down and hiding when fighting Native Americans—essentially imitating their foe’s ambushes. Lest we overlook the obvious, squatting—sitting down—was the exact opposite of standing, which as a noun conveyed the British legal principle of securing territorial rights to the land. The word “right” came from standing erect. One’s legal “standing” meant everything in civilized society.10

“Crackers” first appeared in the records of British officials in the 1760s and described a population with nearly identical traits. In a letter to Lord Dartmouth, one colonial British officer explained that the people called “crackers” were “great boasters,” a “lawless set of rascals on the frontiers of Virginia, Maryland, the Carolinas and Georgia, who often change their places of abode.” As backcountry “banditti,” “villains,” and “horse thieves,” they were dismissed as “idle strag[g]lers” and “a set of vagabonds often worse than the Indians.” By the time of the Revolution, their criminal ways had turned them into ruthless Indian fighters. In one eyewitness account from the Carolina backcountry, a cracker “bruiser” wrestled his Cherokee foe to the ground, gouged out his eyes, scalped his victim alive, and then dashed his skull with the butt of a gun. Overkill was their code of justice.11

Their lineage, as it were, could be traced back to North Carolina, and before that to Virginia’s rejects and renegades. An Anglican minister, Charles Woodmason, who traveled for six years in the Carolina wilderness in the 1760s, offered the most damning portrait of the lazy, licentious, drunken, and whoring men and women whom he adjudged the poorest excuses for British settlers he had ever met. The “Virginia Crackers” he encountered were foolish enough as to argue over a “turd.” The women were “sluttish” by nature, known to pull their clothes tightly around their breasts and hips so as to emphasize their shape. Irreligious men and women engaged in drunken orgies rather than listen to the clergyman’s dull sermons. All in all, crackers were as indolent and immoral as their fellow squatters to the north.12

The origin of “cracker” is no less curious than “squatter.” The “cracking traders” of the 1760s were described as noisy braggarts, prone to lying and vulgarity. One could also “crack” a jest, and crude Englishmen “cracked” wind. Firecrackers gave off a stench and were loud and disruptive as they snapped, crackled, and popped. A “louse cracker” referred to a lice-ridden, slovenly, nasty fellow.13

Another significant linguistic connection to the popular term was the adjective “crack brained,” which denoted a crazy person and was the English slang for a fool or “idle head.” Idleness in mind and body was a defining trait. In one of the most widely read sixteenth-century tracts on husbandry, Thomas Tusser offered the qualifying verse, “Two good haymakers, worth twenty cra[c]kers.” As the embodiment of waste persons, they whittled away time, producing only bluster and nonsense.14

American crackers were aggressive. Their “delight in cruelty” meant they were not just cantankerous but dangerous. As “lawless rascals” of the frontier, they had a lean and mean physique, like an inferior animal. Backwoods traders were easily compared to a “rascally herd” of deer. (“Rascal” was yet another synonym for trash.) As scavengers, crackers were feisty and volatile, or they could play the fool, like Byrd’s slow-witted lubbers.15

In 1798, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote that Pennsylvania squatters had adopted the “strong tincture of the manners” of Indians, particularly in their “violent” fits of labor, “succeeded by long intervals of rest.” Perhaps their southern twins abided by the same instinctive rhythms, but the farther south one went, the more the landless indulged themselves in long periods of sloth. Rush described his state as a “sieve,” leaking southbound squatters. Pennsylvania retained the heartier poor, those willing to plough the stubborn soil, whereas the truly indolent ended up in Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. In Rush’s regional sketch, squatters from the northern states seemed to turn into crackers as soon as they crossed into the southern backcountry.16

✵ ✵ ✵

The persistence of the squatter and cracker allows us to understand how much more limited social mobility was along the frontier than loving legend has it. In the Northwest (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin Territories), the sprawling upper South (Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and Arkansas Territories), and the Floridas (East and West), classes formed in a predictable manner. Speculators and large farmers—a mix of absentee land investors and landowning gentry—had the most power and political influence, and usually had a clear advantage in determining how the land was parceled out. The middling landowners had personal or political connections to the large landowning elite. In new trans-Appalachian towns such as Lexington, Kentucky, dubbed the “Athens of the West,” with the addition of roads came commercial growth between 1815 and 1827, so that a new merchant middle class took root. Such towns as Lexington also supported small farmers, who had less security in retaining their land, given the fluctuations in the market, while artisans of the meaner sort hung about the town.17

With this flood of new settlers, squatters made their presence known. Sometimes identified as families, at other times as single men, they were viewed as a distinct and troublesome class. In the Northwest Territory, they were dismissed as unproductive old soldiers, rubbish that needed to be cleared away before a healthy commercial economy could be established. President Jefferson termed them “intruders” on public lands. Some transients found subsistence as hired laborers. All of them existed on the margins of the commercial marketplace.18

Educated observers feared social disorder, particularly after the financial panic of 1819, when political writers predicted in the West a “numerous population, in a state of wretchedness.” Increasing numbers of poor settlers and uneducated squatters were “ripe for treason and spoil”—a familiar refrain recalling the language circulated during Shays’ Rebellion in 1786. In the wake of the panic, the federal government devised a program of regulated land sales that kept prices high enough to weed out the lowest classes.19

By 1850, in what became a common pattern in new southwestern states, at least 35 percent of the population owned no real estate. There was no clear path to land and riches among the lower ranks. Tenants could easily be reduced to landless squatters. In the Northwest, land agents courted buyers and actively discouraged tenancy. Federal laws for purchasing land were weighted in favor of wealthier speculators. The landless west of the Appalachians were more likely to pull up stakes and move elsewhere than they were to stay in one place and work their way upward.20

The ubiquity of squatters across the United States turned them into a powerful political trope. They came to be associated with five traits: (1) crude habitations; (2) boastful vocabulary; (3) distrust of civilization and city folk; (4) an instinctive love of liberty (read: licentiousness); and (5) degenerate patterns of breeding. Yet even with such unappealing traits, the squatter also acquired some favorable qualities: the simple backwoodsman welcomed strangers into his cabin, the outrageous storyteller entertained them through the night. Squatters, then, were more than troublesome, uncouth rascals taking up land they didn’t own. This double identity made the squatter a contested figure. By the 1830s and 1840s, he was fully a symbol of partisan politics, celebrated as the iconic common man who came to epitomize Jacksonian democracy.

Americans tend to forget that Andrew Jackson was the first westerner elected president. Tall, lanky, with the rawboned look of a true backwoodsman, he wore the harsh life of the frontier on his face and literally carried a bullet next to his heart. Ferocious in his resentments, driven to wreak revenge against his enemies, he often acted without deliberation and justified his behavior as a law unto himself. His controversial reputation made him the target of attacks that painted him as a Tennessee cracker. His wife Rachel’s backcountry divorce and her recourse to both cigar and corncob pipe confirmed the couple as Nashville bumpkins, at least in the eyes of their eastern detractors.21

Jackson and his supporters worked on a different image. During three successive presidential campaigns (1824, 1828, 1832), General Jackson was celebrated as “Old Hickory,” in sharp contrast to Crèvecoeur’s tame analogy of Americans as carefully cultivated plants. Rising up in the harsh hinterland of what was once the western extension of North Carolina, the Tennessean with the unbending will and rigid style of command was a perfect match for the tough, dense wood of Indian bows and hickory switches from which he acquired his nickname.22

Jackson’s personality was a crucial part of his democratic appeal as well as the animosity he provoked. He was the first presidential candidate to be bolstered by a campaign biography. He was not admired for statesmanlike qualities, which he lacked in abundance in comparison to his highly educated rivals John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. His supporters adored his rough edges, his land hunger, and his close identification with the Tennessee wilderness. As a representative of America’s cracker country, Jackson unquestionably added a new class dimension to the meaning of democracy.

But the message of Jackson’s presidency was not about equality so much as a new style of aggressive expansion. In 1818, General Andrew Jackson invaded Florida without presidential approval; as president, he supported the forced removal of the Cherokees from the southeastern states and willfully ignored the opinion of the Supreme Court. Taking and clearing the land, using violent means if necessary, and acting without legal authority, Jackson was arguably the political heir of the cracker and squatter.

✵ ✵ ✵

Over the two decades leading up to Andrew Jackson’s election as president, the squatter and cracker gradually became America’s dominant poor backcountry breed. Not surprisingly, it was their physical environment that most set them apart. In 1810, the ornithologist and poet Alexander Wilson traveled along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from Pittsburgh to New Orleans, cataloguing not only the sky-bound birds but also the earth-hugging squatters, whom he found to be an equally curious species. Writing for a Philadelphia magazine, Wilson identified their “grotesque log cabins” that scarred the otherwise picturesque wilderness.

Weeds surrounded the cabins and huts that the naturalists happened upon. The land showed no sign of toil. Wilson described these questionable homes in mocking poetry as a “cavern’d ruin,” which “frown’d a fouler cave within.” The entire family slept on a single bed, or as Wilson put it, “where nightly kennel’d all.” Kittens crawled into a broken chest, a pig took shelter in a pot, and a leaky roof let in the rain. The squatter patriarch stared from beneath his tattered hat, wearing a shirt “defiled and torn,” his “face inlaid with dirt and soot.”23

For the transplanted Scotsman Wilson, habitat was the measure of a man, marking his capacity for progress or likelihood of decay. If every man’s home was his castle, then America’s backcountry squatters were worse than peasants. With cruel irony, Wilson termed the squatter cabin as a “specimen of the first order of American Architecture.” It amazed him that such uninspired beings could find anything to boast about, yet they proudly spoke of America as the land of opportunity.24

There were many like Wilson who placed squatters below the naked savage on the social scale. At least American Indians belonged in the woods. The poor squatter’s backcountry still carried the association of a rubbish heap. There was no real social ladder emerging in the western territories, no solid foundation for mobility under construction there, not much rising from the bottomless basement that oozed human refuse. From the foothills of the Appalachians into the banks of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, the nation leaned backward. The squatter was frozen in time. His primitive hut represented his underclass cage.

The distance between town and backwoods was measured in more than miles. It had an evolutionary character, forming what some at the time recognized as an impassable gulf between the classes. The educated routinely wrote in disbelief that such people shared their country. In 1817, for example, Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter Cornelia Randolph wrote to her younger sister about a trip with their grandfather to the Natural Bridge, a property that Jefferson owned ninety miles west of Monticello. Here, she said, she encountered members of that “half civiliz’d race who lived beyond the ridge.” The children she met were barely covered by their scanty shifts and shirts, while one man strutted around before them with his “hairy breast exposed.” In this large, unruly family, she noted with disapproval, there were no more than “two or three pairs of shoes.” She was especially surprised by the crude familiarity of their speech. Oblivious to social forms, they conversed with the ex-president as though he was some lost family member. As a proud member of the Virginia gentry, Cornelia was convinced that she towered above the unwashed squatters. To her further chagrin, she was astounded that the poor family exhibited not the least sense of shame over their pathetic condition.25

Class made its most transparent appearance by way of such contrasts. We can read volumes into the scorn expressed by the educated onlooker as he or she sized up the uncouth figures who roamed the backcountry. The need to make them into a new breed focused on more than crude living conditions, however. The backwoodsman and cracker had a telltale gait that accompanied his distinctive physiognomy. While traveling in the trans-Appalachian West in 1830, a city adventurer drolly observed of his bed companion for the night, “lantern-jawed, double-jointed backwoodsman, measuring some seven feet one in his stocking feet.” A typical alligator hunter in southern Illinois bore a similar physique: “gaunt, long-limbed, lanthorn-jawed, Jonathan.” (“Jonathan” simply meant “fellow” here, being a common appellation for a generic American.) The cracker women had the same protruding jaw and swarthy complexion, and were as often as not toothless.26

Women and children were important symbols of civilization—or the absence of it. Officers stationed in Florida in the 1830s identified “ye cracker girls” as brutes, with manners no better than sailors, and often seen smoking pipes, chewing and spitting tobacco, and cursing. Seeing their slipshod dress, dirty feet, ropy hair, and unwashed faces, one lieutenant from the Northeast dismissed them all as no better than prostitutes. In his words, everyone of the cracker class was a “swearing, lazy, idle slut!”27

The backwoods personality could be found as far north as Maine, as far south as Florida, and across the Northwest and Southwest Territories. They acquired localized names, such as Mississippi screamers, for their cracker-style Indian war whoop or love of squealing; Kentucky corn crackers, for their poor diet of cracked corn; and Indiana Hoosiers, for the poor in that state. “Hoosier” is a word no linguistic scholar can define with any precision. Even so, the class descriptor was the same. A Hoosier man ran off at the mouth, lied, boasted, and remained ready to harm anyone who insulted his ugly wife. They were as prone to a down-and-dirty fight as any southern cracker. Hoosier gals were no more refined than their Florida sisters. A Hoosier gal’s courtship ritual, it was said, involved a lot of kicking and hair pulling.28

Sexual behavior was another crucial marker of class status. In a well-known poem of the era, “The Hoosier’s Nest” (1833), the author harkened back to the vocabulary of the Scottish naturalist Wilson. Here again, the cabins were wild nests, a half-human, half-animal retreat perfect for indiscriminate breeding. Using a racially charged slur, the poet identified the children as “Hoosieroons”—a class variation of the mixed-race quadroons. Under their leaky roofs were none of the hearty pioneer stock. Instead, poor Indiana squatters produced a degenerate dozen of dirty yellow urchins.29

Filthy cabins, a lack of manners, and rampant breeding combined to make crackers and squatters a distinct class, as verified by their patterns of speech. Backwoods patois constituted a rural American version of the lower-class English cockney. In 1830, there was even a “Cracker Dictionary,” preserving their vintage slang. One was “Jimber jawed,” whose mouth was constantly moving, who couldn’t stop talking. The cracker’s protruding lower jaw carried over into his style of talking. A “ring tailed roarer” was a violent type; the descriptive “chewed up” literally referred to having one’s ear, nose, or lip bitten off.30

But one polysyllabic word may have best captured their identity. The verb “obsquatulate” was a cracker conjugation of “squat,” conveying the idea of moseying along or absconding. For a people who wouldn’t settle in one place, “obsquatulate” gave an activity of sorts to the American heirs of English vagrants. They might flee like an absconding servant or amble at a slow pace without a destination in mind, but in either case it was their dirty feet and slipshod ways that defined them.31

✵ ✵ ✵

Jackson was not the only Tennessean to become a national celebrity. Though by the 1830s he would come to be known as a bear hunter and “Lion of the West,” David Crockett was a militia scout and lieutenant, justice of the peace, town commissioner, state representative, and finally a U.S. congressman. He was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1827. What makes the historic David Crockett interesting is that he was self-taught, lived off the land, and (most notably for us) became an ardent defender of squatters’ rights—for he had been a squatter himself. As a politician he took up the cause of the landless poor.32

Crockett was born in the “state of Franklin,” a state that was not legally a state. It had declared its independence from North Carolina in 1784 and remained unrecognized. Franklin was later incorporated into Tennessee and became a battleground as speculators and squatters scrambled to control the most arable tracts. Their activities triggered an endless series of skirmishes with the Cherokees, exacerbated by blatant treaty violations. The first governor of Tennessee territory, the prodigious land speculator William Blount, was given the Cherokee nickname “Dirt Captain.” From 1797 to 1811, the federal government periodically sent troops into Tennessee to remove squatters, which only increased these ornery men’s natural hostility toward Washington. To Crockett, a man of humble roots willing to stand his ground, was attributed a simple philosophy: “It’s grit of a fellow that makes a man.” But it wasn’t grit alone that counted; an untamed physicality and fecundity was thought to be the most American of attributes. In 1830, in an unprecedented move, Crockett petitioned Congress to grant a resident of his state a tract of public land—not because of hard work, but because his wife had given birth to triplets.33

As that particular brand of American, the lovable outcast, Crockett acquired a reputation for spinning outrageous tall tales. In a speech he purportedly delivered in Congress (but probably never did give in these exact words) he called himself the “savagest critter you ever did see.” Endowed with superhuman powers, he could “run like a fox, swim like a eel, yell like an Indian,” and “swallow a nigger whole”—an absurd, racist comment that was probably meant to convey his hostility toward great slaveowning planters who pushed poor squatters off their land. The real Crockett owned slaves himself, yet in Congress he opposed large planters’ engrossment of vast tracts of land. He championed a bill that would have sold land directly from the federal government to squatters at low prices. He also opposed the practice of having courts hire out insolvent debtors to work off fees—an updated variation on indentured servitude. Crockett spoke “Cracker” fluently, as was demonstrated in the 1830 dictionary that gave him full credit for coining the phrase “ring-tale roarer” to describe a violent man.34

Crockett’s boasting carried unambiguous class accents. In 1828, he claimed that he could “wade the Mississippi with a steamboat on his back” and “whip his weight in wild cats.” The one thing he said he couldn’t do was to give a standard speech in Congress—which felt odd to him, given that he otherwise believed he could whip any man in the House. He lacked the eloquence that was taught, the argumentation that the educated class possessed. His humorous speeches gained public notoriety, but for many observers he remained the “harlequin,” provoking laughter. According to one newspaper, queer stories and quaint sayings turned Crockett into a dancing bear, dressed up in “coat and breeches,” performing a vulgar sideshow.35

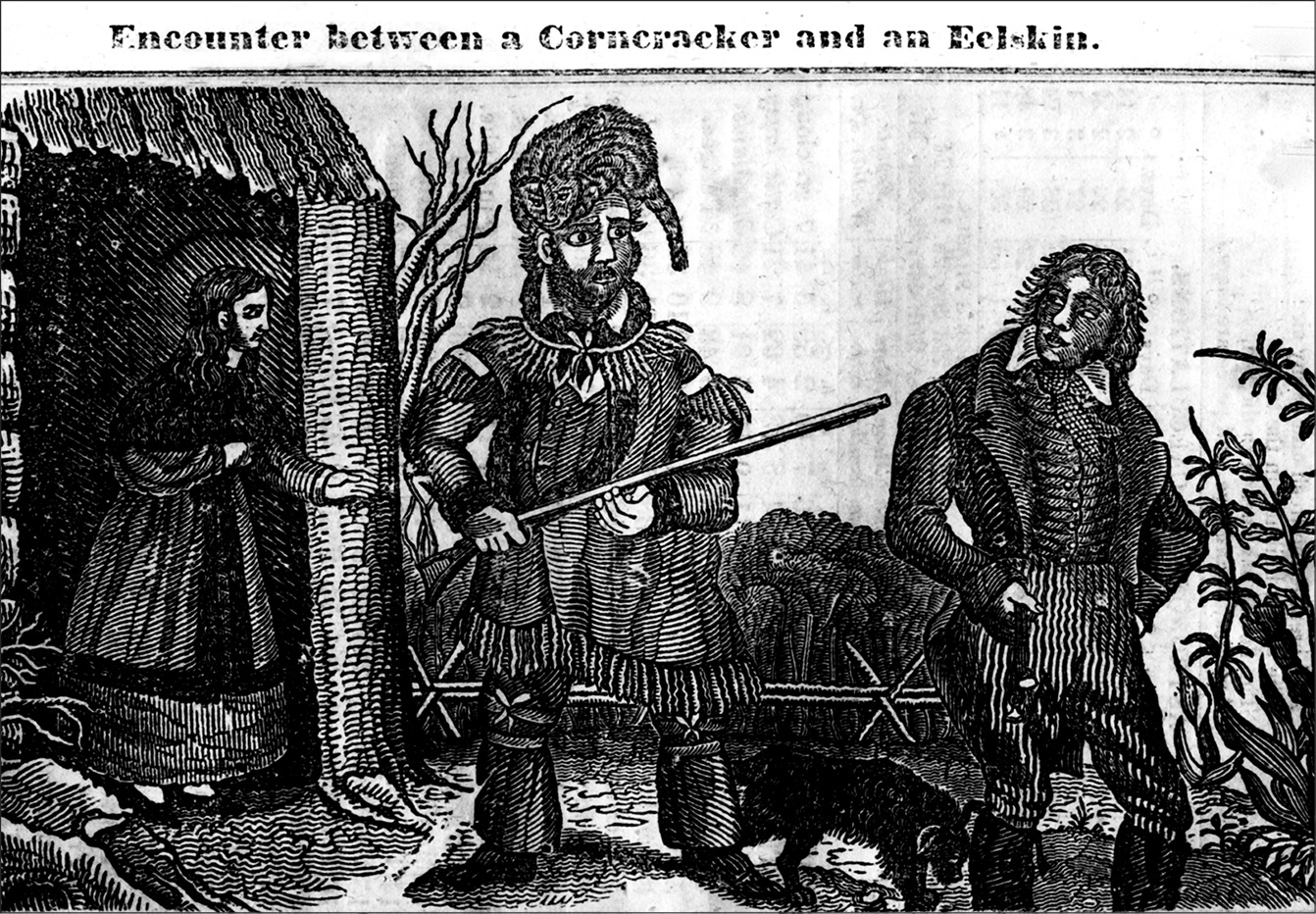

The real Crockett was often eclipsed by the tall tales of the untutored backwoodsman. An entire cottage industry of Crockett stories were published that he never authorized. Davy Crockett’s Almanack of 1837 contains a crude engraving of a corn cracker, who appears unshaven, is dressed in buckskin, and holds a rifle in his hand. He is topped off with a grisly-looking coonskin cap, the animal’s head still attached (see page 121). In another engraving, Davy’s daughter is mounted on a giant alligator’s back, riding the thirty-seven-foot beast like a rodeo star. Whether he fights modern-day dragons or accomplishes magical feats in a surreal hinterland, Crockett’s savage instincts seem appropriate to a mock-chivalric epic. His ghostwriters and hack biographers made Crockett into a wild man and an ill-educated braggart, and yet they equally relished his over-the-top swagger in outmaneuvering steamboats, bears, and slippery town folk.36

His boastfulness was never seen in purely heroic terms. He might jump higher and “squat lower” than “all the fellers either side of the Alleghany hills,” but his comic character actually served to mute a legitimate political voice. Representative Crockett may have compared speculators to sneaky coons in an 1824 speech before the Tennessee House, but he never lost sight of the legal ploys used to trick poorer settlers out of their land warrants. In the end, the man, not the legend, did a better job of exposing class conflict in the backcountry, where real speculators were routinely pitted against real squatters.37

David Crockett was an avid backer of Andrew Jackson in the 1828 election, but soon enough abandoned the imperious general. Crockett’s Land Bill made enemies back in Tennessee, and he disapproved of the Indian Removal Bill, which allowed for forced expulsion of the Cherokees and other “civilized tribes” from the southeastern states. Indian removal went along with the unfair treatment of squatters, who were expelled from the public domain and were barred from securing land that they had settled and improved. Jackson’s allies responded to Crockett’s defection by calling him unsavory and uneducated.

Crockett accused Jackson of going back on his principles, and refused to go along with the partisan dog pack. In 1831, he wrote that he “would not wear a collar round my neck, with ‘my dog’ on it, and the name of ANDREW JACKSON on the collar.” Three years later he made submission to party into an ugly slur, saying he would rather “belong to a nigger, and be a raccoon dog, as the partisan of any man.” In Crockett’s backcountry class hierarchy, there was the free white male landowner, the squatter, the black man, the dog, and then, if his language was to be taken seriously, the party man.38

✵ ✵ ✵

Democrat Andrew Jackson’s stormy relationship with Crockett was replicated again and again with any number of contemporaries over the course of a career that was built on sheer will and utter impulse. Most of his loyal supporters eventually ended up on the opposition side of the partisan divide, joining the Whig Party. Controversy, large and small, seemed to follow the man. Because Jackson had relatively little experience holding political offices, his run for the presidency drew even more than the normal amount of attention to his personal character. A biography written for campaign purposes filled in the gaps in his generally combative résumé. Whether supporters portrayed him as the conquering hero or his enemies labeled him King Andrew I, all focused on his volatile emotions. He certainly lacked the education and polite breeding of his presidential predecessors.39

As an outsider to Washington, save for a brief, unproductive stint in Congress, his qualifications came from the field of war, where his record sparked heated criticism. His ardent backers claimed him as the spiritual successor to the sainted General Washington, but Jackson’s origins lay far from the Potomac, beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Old Hickory had made his home in places where the population was thin and the law fungible. He was a slaveholding planter whose reputation situated him not in the halls of power but among the common stock. In the Tennessee backcountry, where settlement came much later than it did on the East Coast, landowning and class stations ostensibly had shallower roots. As one New England journalist wondered aloud during Jackson’s first run for president in 1824, who precisely were these “hardy sons of the West”?40

In the popular imagination, Jackson was inseparable from a wild and often violent landscape. After his celebrated victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, he was identified as a “green backwoodsman” who had bested the “invincible” British foe. To another, he was “Napoleon of the woods.” His political rise came through violence, having slaughtered the Red Stick faction of the Creek Nation in the swamps of Alabama in 1813-14, while leaving hundreds of British soldiers dead in the marshes of New Orleans in January 1815. Jackson bragged about the British death toll, as did American poets. One extolled, “Carnage stalks wide o’er all the ensanguin’ plain.” And it was no exaggeration. Bodies floated in rivers and streams, and bones of the vanquished were found by travelers decades later.41

Jackson did not look or act like a conventional politician, which was a fundamental part of his appeal. When Jackson arrived in Philadelphia from Tennessee to take his seat in the U.S. Senate in 1796, Pennsylvania congressman Albert Gallatin described a “tall, lank, uncouth-looking personage, with long locks hanging over his face, and a queue down his back tied in eel skin.” In later years, the gaunt general struck observers as stiff in carriage, and weatherworn. Backwater diseases stalked him. Saying nothing of his external appearance, Thomas Jefferson perceived in Jackson a man of savage instincts. Once he observed him so overcome with anger that he was left speechless. (Speechlessness was the classic signifier of primitive man and untamed beast.)42

His fiery temper and lack of scholarly deportment permanently marked him. A sworn enemy put it best: “Boisterous in ordinary conversation, he makes up in oaths what he lacks in arguments.” Not known for his subtle reasoning, Jackson was blunt in his opinions and quick to resent any who disagreed with him. Shouting curses put him in the company of both common soldiers and uncouth crackers. In “A Backwoodsman and a Squatter” (1821), one satirist captured such frontier types, folks known to “squale loose jaw and slam an angry oath.”43

Jackson’s aggressive style, his frequent resorting to duels and street fights, his angry acts of personal and political retaliation seemed to fit what one Frenchman with Jacksonian sympathies described as the westerner’s “rude instinct of masculine liberty.” By this code, independence came from clearing the land of potential threats. The threat could come from Native Americans, rival squatters, political adversaries, or what the corn cracker in Davy Crockett’s Almanack of 1837 described as “eel-skin” easterners who used fancy words to get what they wanted. The cracker’s survivalist ethos invariably trumped legal niceties or polite decorum. It was these traits that shaded Jackson’s public image in the cracker mold.44

After New Orleans, Jackson led his army into Spanish Florida in 1818. He began by raising troops in Tennessee without waiting for the governor’s approval, then invaded East Florida under the guise of arresting a handful of Seminole Indians who were accused of attacking American settlers. When he attacked the fortified Spanish at Pensacola, what had begun as a foray to capture Indians quickly turned into a full-scale war and occupation.45

In Encounter Between a Corncracker and an Eelskin from Davy Crockett’s Almanack of 1837, the backwoods squatter defends his gal from the slippery, seductive words of the trader from town.

Davy Crockett’s Almanack of 1837, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts

Jackson went beyond squatting on Spanish soil. He violated his orders and ignored international law. After overtaking several Florida towns and arresting the Spanish governor, he executed two British citizens without real cause. The British press had a field day, calling the U.S. major general a “ferocious Yankee pirate with blood on his hands.” In a devastating caricature, Jackson appeared as a swarthy, swaggering bandit flanked by a corps of militiamen who were no more than ragged, shoeless brutes, beating drums with bones and wearing skulls instead of hats.46

The pirate who doubled as a backcountry cracker bruiser was unrestrained and unrestrainable. In the Florida invasion, he was reportedly aided by squatters dressed up as “white savages,” who may in fact have been the true catalyst behind Jackson’s controversial action. The Florida conflict had all the signs of a squatters’ war. Soldiers reported that Seminole warriors only attacked “cracker houses,” leaving those of British or northern settlers untouched.47

Prominent critics insisted on a congressional investigation. The powerful Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, demanded the rogue general’s censure. Jackson went to Washington, damned the established legal authorities, and told Secretary of State John Quincy Adams that the entire matter of Florida was between President Monroe and himself—and no one else. Confirmed rumors circulated that Jackson had threatened to cut off the ears of some senators because they had dared to investigate—and humiliate—him on the national stage.48

In Jackson’s crude lexicon, territorial disputes were to be settled by violent means, not by words alone. He explained his Indian policy as the right of “retaliatory vengeance” against “inhumane bloody barbarians.” In 1818, he was heralded in a laudatory biography as a kind of backcountry Moses, administering justice with biblical wrath. To those who protested his lack of regard for international law or constitutional details, defenders claimed that he was “too much a patriot in war, to suffer the scruples of a legal construction.” Yet even the most devoted fans of the general had to admit he had a fiery temper. In 1825, Henry Clay’s highly publicized comment that Jackson was a mere “military chieftain” suggested something tribal, primitive, and wholly unrepublican about him. When he sought the presidency in 1824 and 1828, the Seminole War remained front and center.49

Few of Jackson’s critics were buying the chivalrous portrait his defenders presented. He was not protecting women and children so much as opening up Florida lands to squatters and roughs and other uncivilized whites. But unlike Crockett, Jackson was never a champion of squatters’ rights. When ordered to remove them, he used the military to do the job. Yet at the same time he favored white possession of the land in the same way squatters had always defended their claims: those who cleared and improved the land were worthy occupants. Jackson’s thinking shaped his Indian removal policy as president. He argued that Indians should not be treated as sovereign nations with special claims on the public domain, but as a dependent class. Like squatters, if Indians failed to assimilate or proved incapable of improving the land and securing land titles, they could be forcibly removed. As president, he was more than willing to use force to remove poor trespassers. Only when squatters resisted removal, as they did in Alabama in 1833, and state officials supported them, was President Jackson willing to back down and negotiate more favorable terms for white settlers.50

It was almost too easy for Jackson critics to publicize a counternarrative to the official campaign biography. In 1806, he had shot and killed a young lawyer named Charles Dickinson in a duel, which left him with a bullet next to his heart. While the victim’s body was still warm, he made an ungentlemanly fuss when financial assistance was extended to Dickinson’s widow: in his mind, the scoundrel’s identity had to be permanently erased. According to the retelling of this episode in 1824, Jackson had withheld his shot, stood and watched the offending lawyer tremble, called him a “damn coward,” aimed calmly, and shot him dead at close range. Another incident followed in 1813, when Jackson was party to an impromptu “O.K. Corral” gunfight with his former aide Thomas Hart Benton and his brother Jesse at the Nashville Hotel. In the election year 1828, Thomas Benton made news when he published an account about the near-fatal encounter.51

But nothing looked worse on Jackson’s rap sheet than the so-called Coffin Handbill. He stood accused of executing six of his own men during the Creek War in 1813; six black coffins adorned the 1828 circular. Thus it was not just Indian and English blood that marked him. It was not just the dandyish lawyer Dickinson who met death at Jackson’s hands. In another illustration on the same handbill, Jackson was seen in a down-and-dirty street fight, stabbing a man in the back with a sword hidden inside his cane. Like the cracker fighter who might bite, kick, and lash out indiscriminately, and hide a weapon under his coat, Jackson was seen as thoroughly ruthless—the antithesis of that studied republican gentility meant to define a sober statesman.52

Jackson was perturbed by the caricatures even before the Coffin Handbill made its rounds, writing to a friend in 1824, “Great pains had been taken to represent me as having a savage disposition; who allways [sic] carried a Scalping Knife in one hand & a tomahawk in the other; allways ready to knock down, & scalp, any & every person who differed with me in opinion.” While denying the caricature, he could not deny his violent streak.53

A more appealing, sanitized version of the backwoodsman candidate surfaced in the early 1820s. It portrayed him as an outsider, a man of natural talents drawn from the “native forests,” who was capable of cleaning up the corruption in Washington. His nomination provoked “sneers and derision from the myrmidons of power at Washington,” wrote one avid Jackson man, who decried the “degeneracy of American feeling in that city.” Jackson wasn’t a government minion or a pampered courtier, and thus his unpolished and unstatesmanlike ways were an advantage.54

In 1819, in a speech before Congress, David Walker of Kentucky used this kind of imagery to reproach members of the House for investigating Jackson’s activities in the Seminole War. Walker emphasized the class as well as cultural divide separating representatives in the capital from Americans living on a distant Florida frontier. Jackson’s long experience as the “hardy and weather beaten General” had instilled in him a better sense of judging the conditions of a frontier war. He understood firsthand the suffering and hardships of besieged families. Could the members of the investigation committees fully appreciate the difficulties while sitting at home, their families safe from harm? The men censuring Jackson, whom the Kentucky congressman mocked as the “young sweet-smelling and powdered beau of the town,” were out of their league. With this clever turn of phrase, he recast Jackson’s foes as beaus and dandies, the classic enemies of crackers and squatters.55

Walker had tapped into a dominant class motif of cracker democracy, dating back at least to 1790, when the cracker-versus-beau plotline began to take shape. In its earliest literary form, the cracker buck is lured into town, plied with liquor, and swindled, after which he learns the painful lesson that his dreary cabin in the woods is “where contentment and plenty ever dwell.” A similar story in 1812 told of a backwoodsman curtly dismissing a supercilious lawyer and a capering dancing master who had stood at the door of his cabin. In 1821, clergyman and backcountry historian Joseph Doddridge of western Virginia embellished these stock characters in his play Dialogue of the Backwoodsman and the Dandy. He summed up the peculiar virtues of rough-hewn men:

A Backwoodsman is a queer sort of fellow… . If he’s not a man of larnin, he had plain good sense. If his dress is not fine, his inside works are good and his heart is sound. If he is not rich or great, he knows that he is the father of his country… . You little dandies, and other big folk may freely enjoy the fruits of our hardships; you may feast, where we had to starve; and frolic, where we had to fight; but at peril of all of you, give the Backwoodsman none of your slack-jaw.56

All of this explains Congressman Walker’s point-counterpoint in distinguishing General Jackson from the congressional investigators. The beau was an effete snob, and his ridicule an uncalled-for taunt. The real men of America were Jacksonian, the hearty native sons of Tennessee and Kentucky. They fought the wars. They opened up the frontier through their sacrifice and hardship. They fathered the next generation of courageous settlers. Defensive westerners thus attached to Jackson their dreams and made him a viable presidential candidate.57

Another way to promote their cracker president was through humorous exaggeration. As the different coffin handbills made the rounds in 1828, Jackson’s men used Crockett-like humor to defend him, claiming that the general was really guilty of having eaten the six militiamen, “swallowing them all, coffins and all.” When John Quincy Adams supporters circulated a note written by Jackson filled with misspellings and bad grammar, Jacksonians praised him as “self-taught.” If his lack of diplomatic experience made him “homebred,” this meant that he was less contaminated than the former diplomat Adams by foreign ideas or courtly pomp. The class comparison could not be ignored: Adams had been a professor of rhetoric at Harvard, while his Tennessee challenger was “sprung from a common family,” and had written nothing to brag about. Instinctive action was privileged over unproductive thought.58

Given that his initial support in the 1824 campaign came from Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee, Jackson was derided for having cornered the cracker vote. A humorous piece in a southern newspaper described a Georgia cracker in Crockett prose, “half alligator, half man,” giving a hurrah for Jackson. By 1828, his Indiana constituency was presented as “The Backwoods Alive with Old Hickory.”59

Jackson partisans were routinely chastised for their lack of taste and breeding. At a gathering in Philadelphia in 1828, drinkers lifted their glasses in violent toasts: “May the hickory ramrods ram down the powder of equality into our national guns, and wadded well with the voices of the people to blow Clay in the mud.” Another toastmaster wished that an “Adamite head was a drum head, and me to beat it, till I would beat it in.” Defending Jackson seemed to require threats that celebrated physical prowess over mental agility. If anyone dared insult the “jineral,” went the story told of one Jackson fan, he would give him a “pelt.” Fighting and boasting was paramount in lower-class Jacksonian circles. Or as one cracker candidate pledged as war whoops arose from his anti-Adams audience, “If so I’m elected, Gin’ral government shall wear the print of these five knuckles.”60

In 1828, though two years in the grave, Thomas Jefferson was resurrected to prove that Jackson was of the wrong stock. Jefferson’s former neighbor and longtime secretary of James Madison, Illinois governor Edward Coles, recalled Jefferson’s nasty quip as the 1824 election neared: “One might as well make a sailor a cock, or a soldier a goose, as a President of Andrew Jackson.” High executive office was beyond the reach of Jackson, whose questionable breeding clearly disqualified him.61

The candidate’s private life came under equal scrutiny. His irregular marriage became scandalous fodder during the election of 1828. His intimate circle of Tennessee confidants scrambled to find some justification for the couple’s known adultery. John Overton, Jackson’s oldest and closest friend in Nashville, came up with the story of “accidental bigamy,” claiming that the couple had married in good conscience, thinking that Rachel’s divorce from her first husband had already been decreed. But the truth was something other. Rachel Donelson Robards had committed adultery, fleeing with her paramour Jackson to Spanish-held Natchez in 1790. They had done so not out of ignorance, and not on a lark, but in order to secure a divorce from her husband. Desertion was one of the few recognized causes of divorce.62

In the ever-expanding script detailing Jackson’s misdeeds, adultery was just one more example of his uncontrolled passions. Wife stealing belonged to the standard profile of the backwoods aggressor who refused to believe the law applied to him. In failing to respect international law, he had conquered Florida; in disregarding his wife’s first marriage contract, he simply took what he wanted. Jackson invaded the “sanctity of his neighbor’s matrimonial couch,” as the Ohio journalist Charles Hammond declared.63

All sorts of vicious names were used in demeaning Rachel Jackson. She was called an “American Jezebel,” “weak and vulgar,” and a “dirty black wench,” all of which pointed to her questionable backwoods upbringing. It was pro-Adams editor James G. Dana of Kentucky who luridly painted her as a whore. She could no more pass in polite company, he said with racist outrage, than a gentleman’s black mistress, even if the black wench wore a white mask. Her stain of impurity would never be tolerated among Washington’s better sort. Another unpoliced critic made a similar argument. Her crude conduct might belong in “every cabin beyond the mountains,” he wrote, but not in the President’s House.64

Even without the marriage scandal, Rachel Jackson had the look of a lower-class woman. One visitor to the Jacksons’ home in Tennessee thought she might be mistaken for an old washerwoman. Another described her as fat and her skin tanned, which may explain the “black wench” slur. Whiteness was a badge of class privilege denied to poor cracker gals who worked under the sun. Critics laughed at Mrs. Jackson’s backcountry pronunciation; they made fun of her favorite song, “Possum Up a Gum Tree.” She smoked a pipe. Alas, Rachel Jackson succumbed to heart disease shortly before she was meant to accompany her husband to Washington and take up her duties as First Lady. Her death only intensified the incoming president’s hatred for his political enemies.65

✵ ✵ ✵

To be sure, even beyond class issues, Jackson’s candidacy changed the nature of democratic politics. One political commentator noted that Jackson’s reign ushered in the “game of brag.” Jacksonians routinely exaggerated their man’s credentials, saying he was not just the “Knight of New Orleans,” the country’s “deliverer,” but also the greatest general in all human history. Another observer concluded that a new kind of “talkative country politician” had arisen, who could speak for hours before having finally “exhausted the fountain of his panegyric on General Jackson.”66

Bragging had a distinctive class dimension in the 1820s and 1830s. In a satire published in Tennessee, a writer took note of the strange adaptations of the code of chivalry in defense of honor. The story involved a duel between one Kentucky “Knight of the Red Rag” and a “great and mighty Walnut cracker” of Tennessee. The nutcracker gave himself an exalted title: “duke of Wild Cat Cove, little and big Hog Thief Creek, Short Mountain, Big Bore Cave and Cuwell’s Bridge.” So what did this kind of posturing mean? Like certain masters of gangsta rap in the twenty-first century, crackers had to make up for their lowly status by dressing themselves up in a boisterous verbal garb. In the Crockett manner, lying and boasting made up for the absence of class pedigree. This, too, was Andrew Jackson. He used duels, feuds, and oaths to rise in the political pecking order in the young state of Tennessee.67

While Jackson had little interest in squatters’ rights, his party did shift the debate in their favor. Democrats supported preemption rights, which made it easier and cheaper for those lacking capital to purchase land. Preemption granted squatters the right to settle, to improve, and then to purchase the land they occupied at a “minimum price.” The debate over preemption cast the squatter in a more favorable light. For some, he was now a hardworking soul who built his cabin with his own hands and had helped to clear the land, which benefited all classes. The Whig leader Henry Clay found himself on the losing side of the debate. In 1838, Clay joked in the Senate that the preemptioner might take his newfound rights and squat down in the spacious White House occupied by one “little man”—Jackson’s handpicked successor, Martin Van Buren.68

Thomas Hart Benton, in quitting Tennessee and moving to Missouri, buried the hatchet with Jackson. As an eminent senator during and after Jackson’s two terms in office, he pushed through preemption laws, culminating in the “Log Cabin Bill” of 1841. But Benton’s thinking was double-edged: yes, he wished to give squatters a chance to purchase a freehold, but he was not above treating them as an expendable population. In 1839, he proposed arming squatters, giving them land and rations as an alternative to renewing the federal military campaign against the Seminoles in Florida. By this, Benton merely revived the British military tactic of using squatters as an inexpensive tool for conquering the wilderness.69

The presidential campaign of 1840 appears to be the moment when the squatter morphed into the colloquial common man of democratic lore. Both parties now embraced him. Partisans of Whig presidential candidate William Henry Harrison claimed that he was from backwoods stock. This was untrue. Harrison was born into an elite Virginia planter family, and though he had been briefly a cabin dweller in the Old Northwest Territory, by the time he ran for office that cabin had been torn down and replaced with a grand mansion. Kentuckian Henry Clay, who vied with him for the Whig nomination, celebrated his prizewinning mammoth hog—named “Corn Cracker,” no less. The new class politics played out in trumped-up depictions of log cabins, popular nicknames, hard-cider drinking, and coonskin caps. This imagery explains why westerners and the poorer voters never fully embraced Jackson’s favorite, Martin Van Buren, who was seen as a dandyish eastern bachelor. In one Whig-inspired campaign song, the Dutch-descended New Yorker was blasted as a “queer little man … mounted on the back of the sturdy Andy Jack.”70

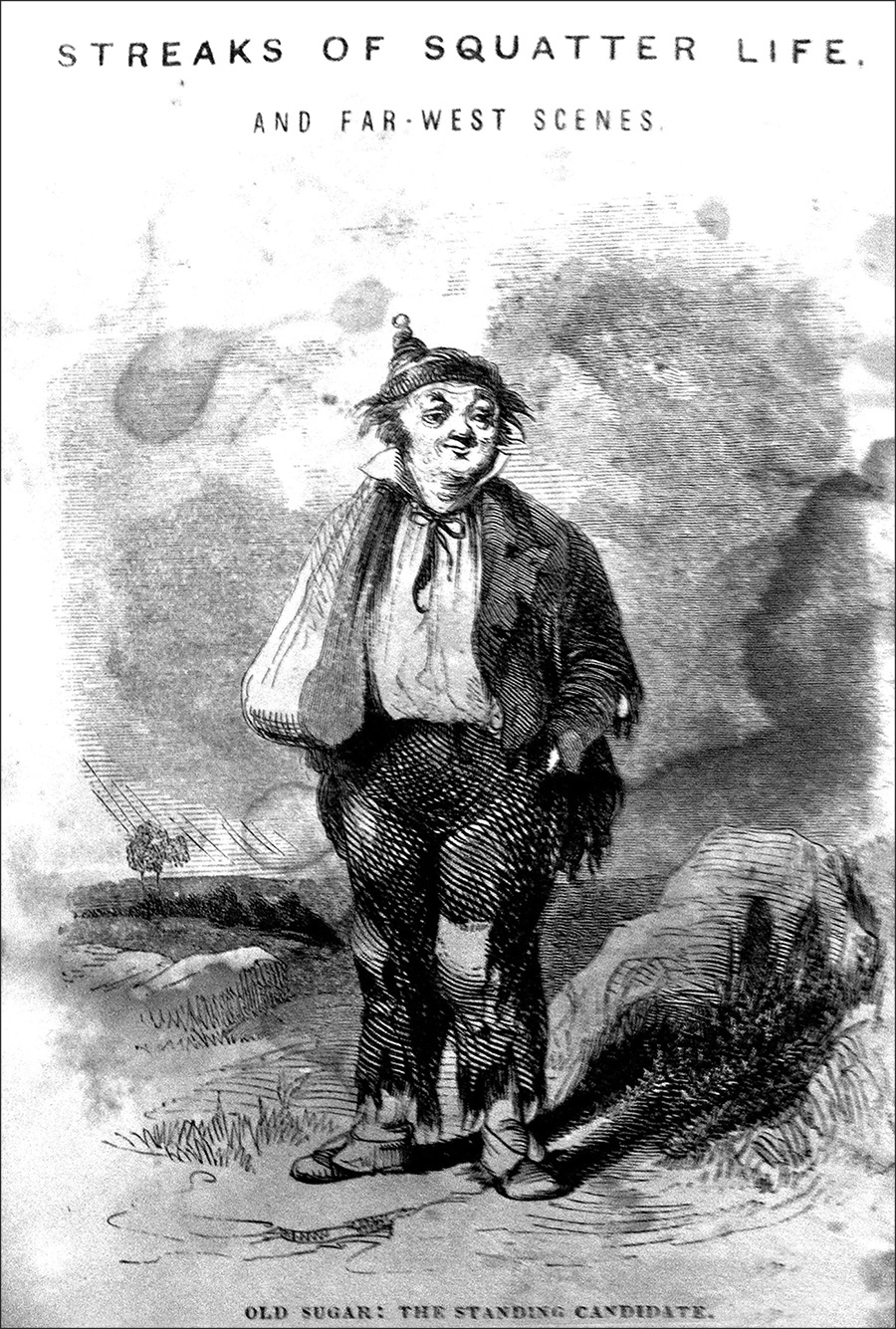

The squatter all at once became a romantic figure in popular culture. This was true in St. Louis newspaperman John Robb’s Streaks of Squatter Life. In one of the stories in the collection, Robb introduced a poor white Missouri squatter named Sugar. Though he was dressed in rags, his personal influence over local elections was hypnotic. At the polling place, “Sug” came with a keg of whiskey, which he sweetened with brown sugar. As members of the crowd lined up for his special concoction, he told them, based on his honest opinion of the speeches he had heard, whom they should vote for. Sug had lost his girl and his farm, and yet as a landless squatter he somehow gained respect. He represented the new common man, a simple fellow who couldn’t be misled by fancy rhetoric.71

Sug was not simply a leveling character. He actually represented a reformed, even middle-class solution to the larger debate over class and respectability. His qualities suggested a reasonable man who handed out a little whiskey and dispensed meaningful advice. He wasn’t running for office. He wasn’t brawling or bartering whiskey for votes. He wasn’t threatening the life of a rival bidder over a tract of land. Sug knew his place as the neighborhood purveyor of common sense.72

“Old Sug” in Streaks of Squatter Life (1847) is a comic character whose poverty is rendered harmless. He represented a softened image of actual squatters known for brawling, drinking, and swearing at political events in the backcountry.

John Robb’s Streaks of Squatter Life (1847), American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts

The squatter may have been tamed, at least in the minds of some, but political equality did not come to America in the so-called Age of Jackson. Virginia retained property qualifications for voting until 1851; Louisiana and Connecticut until 1845; North Carolina until 1857. Tennessee did not drop its freehold restriction until 1834—after Jackson had already been elected to a second term. Eight states passed laws that disenfranchised paupers, the urban poor. Meanwhile many towns and cities adopted stricter suffrage guidelines for voting than their state legislatures did. This was true for Chicago, and for towns in Crockett’s Tennessee and pro-Jackson Alabama. He could vote for a member of Congress, but in John Robb’s St. Louis, his fictional pal Sug would have been denied the right to vote in municipal elections.73

The heralded democrat Andrew Jackson (as it was pointed out in the 1828 campaign) had actually helped draft suffrage restrictions for the Tennessee constitution in 1796. He made no effort to expand the electorate in his state—ever. As the territorial governor of Florida in 1822, he was perfectly comfortable with the new state’s imposing property requirements for voting. Jackson’s appeal as a presidential candidate was not about real democracy, then, but instead the attraction to a certain class of land-grabbing whites and the embrace of the “rude instinct of masculine liberty.” He did not stand for universal male suffrage. Indeed, it was not the United States, but Liberia, a country founded by the British and former American slaves, that first established universal suffrage for adult men, in 1839.74

In the end, the cracker or squatter never resolved his paradoxical character. He could free himself of responsibility, take to the road, and start over. He could boast and brag and pelt anyone who dared to insult his favorite candidate. As many have pointed out, whiskey drinking at the polls was often more important than listening to long-winded speeches. So while some journalists defended the “country crackers” as the “bone and sinew of the country,” others continued to see the cracker as a drunken fool who, as one writer put it, elevated a favorite stump speaker into a “demigod of beggars.” As late as 1842, “squatter” was still considered a “term, denoting infamy of life or station,” of a lesser rank than the class-neutral “settler.”75

Thus, the cracker or squatter was never the poster child of political equality. As a figure of popular caricature, he was a vivid illustration of class distinction more than he ever was a sign of respect for the lower class. No one pretended that Sug was the equal of John Quincy Adams, William Henry Harrison, or even his local congressman. At best, a backcountry citizen might get a chance to meet President Adams, but shaking hands (in the now familiar, post-bowing fashion) did not result in an elevation in social rank. In 1828, James Fenimore Cooper observed that democratic boasting was a “cheap price” to pay for ensuring that real social leveling did not erode set-in-stone class divisions.76

There was one bit of lore that concerned the squatter that did take hold. He had to be wooed for his vote. He had no patience for a candidate who refused to speak his language. That was the moral of another famous squatter story of 1840, “The Arkansas Traveller,” in which an elite politician canvassing in the backcountry asks a squatter for refreshment. The squatter, seated on a whiskey barrel before his run-down cabin, ignores the man’s request. For a brief interlude (because it was election season), the politician was obliged to bring himself down to the level of the common man. To get his drink and the squatter’s vote, the politician had to dismount his horse, grab the squatter’s fiddle, and show that he could play his kind of music. Once the politician returned to his mansion, however, nothing had changed in the life of the squatter, nor for his drudge of a wife and his brood of dirty, shoeless brats.77